Consciousness Studies/Seventeenth And Eighteenth Century Philosophy

Rene Descartes (1596-1650)

[edit | edit source]Descartes was also known as Cartesius. He had an empirical approach to consciousness and the mind, describing in his Meditations on First Philosophy (1641) what it is like to be human. His idea of perception is summarised in the diagram below.

Dubitability

[edit | edit source]Descartes is probably most famous for his statement:

"But immediately upon this I observed that, whilst I thus wished to think that all was false, it was absolutely necessary that I, who thus thought, should be somewhat; and as I observed that this truth, I think, therefore I am (COGITO ERGO SUM), was so certain and of such evidence that no ground of doubt, however extravagant, could be alleged by the sceptics capable of shaking it, I concluded that I might, without scruple, accept it as the first principle of the philosophy of which I was in search."

Descartes is clear that what he means by thought is all the things that occur in experience, whether dreams, sensations, symbols etc.:

"5. Of my thoughts some are, as it were, images of things, and to these alone properly belongs the name IDEA; as when I think [ represent to my mind ] a man, a chimera, the sky, an angel or God. Others, again, have certain other forms; as when I will, fear, affirm, or deny, I always, indeed, apprehend something as the object of my thought, but I also embrace in thought something more than the representation of the object; and of this class of thoughts some are called volitions or affections, and others judgments." (Meditation III).

He repeats this general description of thought in many places in the Meditations and elsewhere. What Descartes is saying is that his meditator has thoughts; that there are thoughts and this cannot be doubted when and where they occur (Russell (1945) makes this clear).

Needless to say the basic cogito put forward by Descartes has provoked endless debate, much of it based on the false premise that Descartes was presenting an inference or argument rather than just saying that thought certainly exists. However, the extent to which the philosopher can go beyond this certainty to concepts such as God, science or the soul is highly problematical.

The description of thoughts and mind

[edit | edit source]

Descartes uses the words "ideas" and "imagination" in a rather unusual fashion. The word "idea" he defines as follows:

"5. Of my thoughts some are, as it were, images of things, and to these alone properly belongs the name IDEA; as when I think [ represent to my mind ] a man, a chimera, the sky, an angel or God." (Meditation III).

As will be seen later, Descartes regards his mind as an unextended thing (a point) so "images of things" or "IDEAS" require some way of being extended. In the Treatise on Man (see below) he is explicit that ideas are extended things in the brain, on the surface of the "common sense". In Rules for the Direction of the Mind he notes that we "receive ideas from the common sensibility", an extended part of the brain. This usage of the term "ideas" is very strange to the modern reader and the source of many mistaken interpretations. It should be noted that occasionally Descartes uses the term 'idea' according to its usual meaning where it is almost interchangeable with 'thought' in general but usually he means a representation laid out in the brain.

Descartes considers the imagination to be the way that the mind "turns towards the body" (by which Descartes means the part of the brain in the body called the senses communis):

"3. I remark, besides, that this power of imagination which I possess, in as far as it differs from the power of conceiving, is in no way necessary to my [nature or] essence, that is, to the essence of my mind; for although I did not possess it, I should still remain the same that I now am, from which it seems we may conclude that it depends on something different from the mind. And I easily understand that, if some body exists, with which my mind is so conjoined and united as to be able, as it were, to consider it when it chooses, it may thus imagine corporeal objects; so that this mode of thinking differs from pure intellection only in this respect, that the mind in conceiving turns in some way upon itself, and considers some one of the ideas it possesses within itself; but in imagining it turns toward the body, and contemplates in it some object conformed to the idea which it either of itself conceived or apprehended by sense." Meditations VI

So ideas, where they become imagined images of things were thought by Descartes to involve a phase of creating a form in the brain.

Descartes gives a clear description of his experience as a container that allows length, breadth, depth, continuity and time with contents arranged within it:

"2. But before considering whether such objects as I conceive exist without me, I must examine their ideas in so far as these are to be found in my consciousness, and discover which of them are distinct and which confused.

3. In the first place, I distinctly imagine that quantity which the philosophers commonly call continuous, or the extension in length, breadth, and depth that is in this quantity, or rather in the object to which it is attributed. Further, I can enumerate in it many diverse parts, and attribute to each of these all sorts of sizes, figures, situations, and local motions; and, in fine, I can assign to each of these motions all degrees of duration."(Meditation V).

He points out that sensation occurs by way of the brain, conceptualising the brain as the place in the body where the extended experiences are found : Meditations VI:

"20. I remark, in the next place, that the mind does not immediately receive the impression from all the parts of the body, but only from the brain, or perhaps even from one small part of it, viz., that in which the common sense (senses communis) is said to be, which as often as it is affected in the same way gives rise to the same perception in the mind, although meanwhile the other parts of the body may be diversely disposed, as is proved by innumerable experiments, which it is unnecessary here to enumerate."

He finds that both imaginings and perceptions are extended things and hence in the (brain part) of the body. The area of extended things is called the res extensa, it includes the brain, body and world beyond. He also considers the origin of intuitions, suggesting that they can enter the mind without being consciously created: Meditations VI, 10 :

"10. Moreover, I find in myself diverse faculties of thinking that have each their special mode: for example, I find I possess the faculties of imagining and perceiving, without which I can indeed clearly and distinctly conceive myself as entire, but I cannot reciprocally conceive them without conceiving myself, that is to say, without an intelligent substance in which they reside, for [in the notion we have of them, or to use the terms of the schools] in their formal concept, they comprise some sort of intellection; whence I perceive that they are distinct from myself as modes are from things. I remark likewise certain other faculties, as the power of changing place, of assuming diverse figures, and the like, that cannot be conceived and cannot therefore exist, any more than the preceding, apart from a substance in which they inhere. It is very evident, however, that these faculties, if they really exist, must belong to some corporeal or extended substance, since in their clear and distinct concept there is contained some sort of extension, but no intellection at all. Further, I cannot doubt but that there is in me a certain passive faculty of perception, that is, of receiving and taking knowledge of the ideas of sensible things; but this would be useless to me, if there did not also exist in me, or in some other thing, another active faculty capable of forming and producing those ideas. But this active faculty cannot be in me [in as far as I am but a thinking thing], seeing that it does not presuppose thought, and also that those ideas are frequently produced in my mind without my contributing to it in any way, and even frequently contrary to my will. This faculty must therefore exist in some substance different from me, in which all the objective reality of the ideas that are produced by this faculty is contained formally or eminently, as I before remarked; and this substance is either a body, that is to say, a corporeal nature in which is contained formally [and in effect] all that is objectively [and by representation] in those ideas; or it is God himself, or some other creature, of a rank superior to body, in which the same is contained eminently. But as God is no deceiver, it is manifest that he does not of himself and immediately communicate those ideas to me, nor even by the intervention of any creature in which their objective reality is not formally, but only eminently, contained. For as he has given me no faculty whereby I can discover this to be the case, but, on the contrary, a very strong inclination to believe that those ideas arise from corporeal objects, I do not see how he could be vindicated from the charge of deceit, if in truth they proceeded from any other source, or were produced by other causes than corporeal things: and accordingly it must be concluded, that corporeal objects exist. Nevertheless, they are not perhaps exactly such as we perceive by the senses, for their comprehension by the senses is, in many instances, very obscure and confused; but it is at least necessary to admit that all which I clearly and distinctly conceive as in them, that is, generally speaking all that is comprehended in the object of speculative geometry, really exists external to me. "

He considers that the mind itself is the thing that generates thoughts and is not extended (occupies no space). This 'mind' is known as the res cogitans. The mind works on the imaginings and perceptions that exist in that part of the body called the brain. This is Descartes' dualism: it is the proposition that there is an unextended place called the mind that acts upon the extended things in the brain. Meditations VI, 9:

"... And although I may, or rather, as I will shortly say, although I certainly do possess a body with which I am very closely conjoined; nevertheless, because, on the one hand, I have a clear and distinct idea of myself, in as far as I am only a thinking and unextended thing, and as, on the other hand, I possess a distinct idea of body, in as far as it is only an extended and unthinking thing, it is certain that I, [that is, my mind, by which I am what I am], is entirely and truly distinct from my body, and may exist without it."

Notice that the intellection associated with ideas is part of an "active faculty capable of forming and producing those ideas" that has a "corporeal nature" (it is in the brain). This suggests that the "thinking" in the passage above applies only to those thoughts that are unextended, however, it is difficult to find a definition of these particular thoughts.

"Rules for the Direction of the Mind" demonstrates Descartes' dualism. He describes the brain as the part of the body that contains images or phantasies of the world but believes that there is a further, spiritual mind that processes the images in the brain:

"My fourth supposition is that the power of movement, in fact the nerves, originate in the brain, where the phantasy is seated; and that the phantasy moves them in various ways, as the external sense <organ> moves the <organ of> common sensibility, or as the whole pen is moved by its tip. This illustration also shows how it is that the phantasy can cause various movements in the nerves, although it has not images of these formed in itself, but certain other images, of which these movements are possible effects. For the pen as a whole does not move in the same way as its tip; indeed, the greater part of the pen seems to go along with an altogether different, contrary motion. This enables us to understand how the movements of all other animals are accomplished, although we suppose them to have no consciousness (rerum cognitio) but only a bodily <organ of> phantasy; and furthermore, how it is that in ourselves those operations are performed which occur without any aid of reason.

My fifth and last supposition is that the power of cognition properly so called is purely spiritual, and is just as distinct from the body as a whole as blood is from bone or a hand from an eye; and that it is a single power. Sometimes it receives images from the common sensibility at the same time as the phantasy does; sometimes it applies itself to the images preserved in memory; sometimes it forms new images, and these so occupy the imagination that often it is not able at the same time to receive ideas from the common sensibility, or to pass them on to the locomotive power in the way that the body left to itself -would. "

Descartes sums up his concept of a point soul seeing forms in the world via forms in the sensus communis in Passions of the Soul, 35:

"By this means the two images which are in the brain form but one upon the gland, which, acting immediately upon the soul, causes it to see the form in the mind".

Anatomical and physiological ideas

[edit | edit source]In his Treatise on Man Descartes summarises his ideas on how we perceive and react to things as well as how consciousness is achieved anatomically and physiologically. The 'Treatise' was written at a time when even galvanic electricity was unknown. The excerpt given below covers Descartes' analysis of perception and stimulus-response processing.

"Thus for example [in Fig 1], if fire A is close to foot B, the tiny parts of this fire (which, as you know, move about very rapidly) have the power also to move the area of skin which they touch. In this way they pull the tiny fibre cc which you see attached to it, and simultaneously open the entrance to the pore de, located opposite the point where this fiber terminates - just as when you pull one end of a string, you cause a bell hanging at the other end to ring at the same time.

When the entrance to the pore or small tube de is opened in this way, the animal spirits from cavity F enter and are carried through it - some to muscles which serve to pull the foot away from the fire, some to muscles which turn the eyes and head to look at it, and some to muscles which make the hands move and the whole body turn in order to protect it.

Now I maintain that when God unites a rational soul to this machine (in a way that I intend to explain later) he will place its principle seat in the brain, and will make its nature such that the soul will have different sensations corresponding to the different ways in which the entrances to the pores in the internal surface of the brain are opened by means of nerves.

In order to see clearly how ideas are formed of the objects which strike the senses, observe in this diagram [fig 2] the tiny fibres 12, 34, 56, and the like, which make up the optic nerve and stretch from the back of the eye at 1, 3, 5 to the internal surface of the brain at 2, 4, 6. Now assume that these fibres are so arranged that if the rays coming, for example, from point A of the object happen to press upon the back of the eye at point 1, they pull the whole of fibre 12 and enlarge the opening of the tiny tube marked 2. In the same way, the rays which come from point B enlarge the opening of the tiny tube 4, and likewise for the others. We have already described how, depending on the different ways in which the points 1, 3, 5 are pressed by these rays, a figure is traced on the back of the eye corresponding to that of the object ABC. Similarly it is obvious that, depending on the different ways in which the tiny tubes 2, 4, 6 are opened by the fibres 12, 34, 56 etc., a corresponding figure must also be traced on the internal surface of the brain.

.....

And note that by 'figures' I mean not only things which somehow represent the position of the edges and surfaces of objects, but also anything which, as I said above, can give the soul occasion to perceive movement, size, distance, colours, sounds, smells and other such qualities. And I also include anything that can make the soul feel pleasure, pain, hunger, thirst, joy, sadness and other such passions.

...

Now among these figures, it is not those imprinted on the external sense organs, or on the internal surface of the brain, which should be taken to be ideas - but only those which are traced in the spirits on the surface of gland H (where the seat of the imagination and the 'common sense' is located). That is to say, it is only the latter figures which should be taken to be the forms or images which the rational soul united to this machine will consider directly when it imagines some object or perceives it by the senses.

And note that I say 'imagines or perceives by the senses'. For I wish to apply the term 'idea' generally to all impressions which the spirits can receive as they leave gland H. These are to be attributed to the 'common' sense when they depend on the presence of objects; but they may also proceed from many other causes (as I shall explain later), and they should then be attributed to the imagination. "

The common sense is referred to by philosophers as the senses communis. Descartes considered this to be the place where all the sensations were bound together and proposed the pineal gland for this role. This was in the days before the concept of 'dominance' of parts of the brain had been developed so Descartes reasoned that only a single organ could host a bound representation.

Notice how Descartes is explicit about ideas being traced in the spirits on the surface of the gland. Notice also how the rational soul will consider forms on the common sense directly.

Descartes believed that animals are not conscious because, although he thought they possessed the stimulus-response loop in the same way as humans he believed that they do not possess a soul.

John Locke (1632-1704)

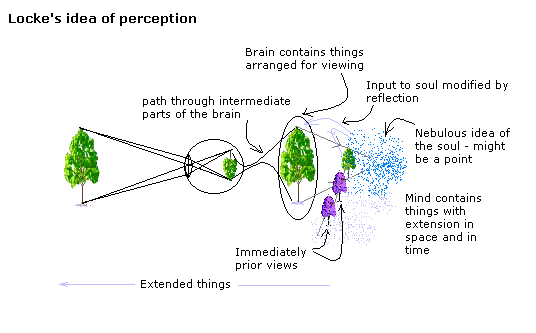

[edit | edit source]Locke's most important philosophical work on the human mind was "An Essay Concerning Human Understanding" written in 1689. His idea of perception is summarised in the diagram below:

Locke is an Indirect Realist, admitting of external objects but describing these as represented within the mind. The objects themselves are thought to have a form and properties that are the archetype of the object and these give rise in the brain and mind to derived copies called ektypa.

Like Descartes, he believes that people have souls that produce thoughts. Locke considers that sensations make their way from the senses to the brain where they are laid out for understanding as a 'view':

"And if these organs, or the nerves which are the conduits to convey them from without to their audience in the brain,- the mind's presence-room (as I may so call it)- are any of them so disordered as not to perform their functions, they have no postern to be admitted by; no other way to bring themselves into view, and be perceived by the understanding." (Chapter III, 1).

He considers that what is sensed becomes a mental thing: Chapter IX: Of Perception paragraph 1:

"This is certain, that whatever alterations are made in the body, if they reach not the mind; whatever impressions are made on the outward parts, if they are not taken notice of within, there is no perception. Fire may burn our bodies with no other effect than it does a billet, unless the motion be continued to the brain, and there the sense of heat, or idea of pain, be produced in the mind; wherein consists actual perception. "

Locke calls the contents of consciousness "ideas" (cf: Descartes, Malebranche) and regards sensation, imagination etc. as being similar or even alike. Chapter I: Of Ideas in general, and their Original:

"1. Idea is the object of thinking. Every man being conscious to himself that he thinks; and that which his mind is applied about whilst thinking being the ideas that are there, it is past doubt that men have in their minds several ideas,- such as are those expressed by the words whiteness, hardness, sweetness, thinking, motion, man, elephant, army, drunkenness, and others: it is in the first place then to be inquired, How he comes by them?

I know it is a received doctrine, that men have native ideas, and original characters, stamped upon their minds in their very first being. This opinion I have at large examined already; and, I suppose what I have said in the foregoing Book will be much more easily admitted, when I have shown whence the understanding may get all the ideas it has; and by what ways and degrees they may come into the mind;- for which I shall appeal to every one's own observation and experience.

2. All ideas come from sensation or reflection. Let us then suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper, void of all characters, without any ideas:- How comes it to be furnished? Whence comes it by that vast store which the busy and boundless fancy of man has painted on it with an almost endless variety? Whence has it all the materials of reason and knowledge? To this I answer, in one word, from EXPERIENCE. In that all our knowledge is founded; and from that it ultimately derives itself. Our observation employed either, about external sensible objects, or about the internal operations of our minds perceived and reflected on by ourselves, is that which supplies our understandings with all the materials of thinking. These two are the fountains of knowledge, from whence all the ideas we have, or can naturally have, do spring.

3. The objects of sensation one source of ideas. First, our Senses, conversant about particular sensible objects, do convey into the mind several distinct perceptions of things, according to those various ways wherein those objects do affect them. And thus we come by those ideas we have of yellow, white, heat, cold, soft, hard, bitter, sweet, and all those which we call sensible qualities; which when I say the senses convey into the mind, I mean, they from external objects convey into the mind what produces there those perceptions. This great source of most of the ideas we have, depending wholly upon our senses, and derived by them to the understanding, I call SENSATION.

4. The operations of our minds, the other source of them. Secondly, the other fountain from which experience furnisheth the understanding with ideas is,- the perception of the operations of our own mind within us, as it is employed about the ideas it has got;- which operations, when the soul comes to reflect on and consider, do furnish the understanding with another set of ideas, which could not be had from things without. And such are perception, thinking, doubting, believing, reasoning, knowing, willing, and all the different actings of our own minds;- which we being conscious of, and observing in ourselves, do from these receive into our understandings as distinct ideas as we do from bodies affecting our senses. This source of ideas every man has wholly in himself; and though it be not sense, as having nothing to do with external objects, yet it is very like it, and might properly enough be called internal sense. But as I call the other SENSATION, so I Call this REFLECTION, the ideas it affords being such only as the mind gets by reflecting on its own operations within itself. By reflection then, in the following part of this discourse, I would be understood to mean, that notice which the mind takes of its own operations, and the manner of them, by reason whereof there come to be ideas of these operations in the understanding. These two, I say, viz. external material things, as the objects of SENSATION, and the operations of our own minds within, as the objects of REFLECTION, are to me the only originals from whence all our ideas take their beginnings. The term operations here I use in a large sense, as comprehending not barely the actions of the mind about its ideas, but some sort of passions arising sometimes from them, such as is the satisfaction or uneasiness arising from any thought.

5. All our ideas are of the one or the other of these. The understanding seems to me not to have the least glimmering of any ideas which it doth not receive from one of these two. External objects furnish the mind with the ideas of sensible qualities, which are all those different perceptions they produce in us; and the mind furnishes the understanding with ideas of its own operations. "

He calls ideas that come directly from the senses primary qualities and those that come from reflection upon these he calls secondary qualities:

"9. Primary qualities of bodies. Qualities thus considered in bodies are, First, such as are utterly inseparable from the body, in what state soever it be; and such as in all the alterations and changes it suffers, all the force can be used upon it, it constantly keeps; and such as sense constantly finds in every particle of matter which has bulk enough to be perceived; and the mind finds inseparable from every particle of matter, though less than to make itself singly be perceived by our senses: .......... These I call original or primary qualities of body, which I think we may observe to produce simple ideas in us, viz. solidity, extension, figure, motion or rest, and number. 10. Secondary qualities of bodies. Secondly, such qualities which in truth are nothing in the objects themselves but power to produce various sensations in us by their primary qualities....." (Chapter VIII).

He gives examples of secondary qualities:

"13. How secondary qualities produce their ideas. After the same manner, that the ideas of these original qualities are produced in us, we may conceive that the ideas of secondary qualities are also produced, viz. by the operation of insensible particles on our senses. .....v.g. that a violet, by the impulse of such insensible particles of matter, of peculiar figures and bulks, and in different degrees and modifications of their motions, causes the ideas of the blue colour, and sweet scent of that flower to be produced in our minds. It being no more impossible to conceive that God should annex such ideas to such motions, with which they have no similitude, than that he should annex the idea of pain to the motion of a piece of steel dividing our flesh, with which that idea hath no resemblance." (Chapter VIII).

He argues against all conscious experience being in mental space (does not consider that taste might be on the tongue or a smell come from a cheese): Chapter XIII: Complex Ideas of Simple Modes:- and First, of the Simple Modes of the Idea of Space - paragraph 25:

"I shall not now argue with those men, who take the measure and possibility of all being only from their narrow and gross imaginations: but having here to do only with those who conclude the essence of body to be extension, because they say they cannot imagine any sensible quality of any body without extension,- I shall desire them to consider, that, had they reflected on their ideas of tastes and smells as much as on those of sight and touch; nay, had they examined their ideas of hunger and thirst, and several other pains, they would have found that they included in them no idea of extension at all, which is but an affection of body, as well as the rest, discoverable by our senses, which are scarce acute enough to look into the pure essences of things."

Locke understood the "specious" or extended present but conflates this with longer periods of time: Chapter XIV. Idea of Duration and its Simple Modes - paragraph 1:

"Duration is fleeting extension. There is another sort of distance, or length, the idea whereof we get not from the permanent parts of space, but from the fleeting and perpetually perishing parts of succession. This we call duration; the simple modes whereof are any different lengths of it whereof we have distinct ideas, as hours, days, years, &c., time and eternity."

Locke is uncertain about whether extended ideas are viewed from an unextended soul.

"He that considers how hardly sensation is, in our thoughts, reconcilable to extended matter; or existence to anything that has no extension at all, will confess that he is very far from certainly knowing what his soul is. It is a point which seems to me to be put out of the reach of our knowledge: and he who will give himself leave to consider freely, and look into the dark and intricate part of each hypothesis, will scarce find his reason able to determine him fixedly for or against the soul's materiality. Since, on which side soever he views it, either as an unextended substance, or as a thinking extended matter, the difficulty to conceive either will, whilst either alone is in his thoughts, still drive him to the contrary side."(Chapter III, 6).

David Hume (1711-1776)

[edit | edit source]Hume (1739–40). A Treatise of Human Nature: Being An Attempt to Introduce the Experimental Method of Reasoning Into Moral Subjects.

Hume represents a type of pure empiricism where certainty is only assigned to present experience. As we can only directly know the mind he works within this constraint. He admits that there can be consistent bodies of knowledge within experience and would probably regard himself as an Indirect Realist but with the caveat that the things that are inferred to be outside the mind, in the physical world, could be no more than inferences within the mind.

Hume has a clear concept of mental space and time that is informed by the senses:

"The idea of space is convey'd to the mind by two senses, the sight and touch; nor does anything ever appear extended, that is not either visible or tangible. That compound impression, which represents extension, consists of several lesser impressions, that are indivisible to the eye or feeling, and may be call'd impressions of atoms or corpuscles endow'd with colour and solidity. But this is not all. 'Tis not only requisite, that these atoms shou'd be colour'd or tangible, in order to discover themselves to our senses; 'tis also necessary we shou'd preserve the idea of their colour or tangibility in order to comprehend them by our imagination. There is nothing but the idea of their colour or tangibility, which can render them conceivable by the mind. Upon the removal of the ideas of these sensible qualities, they are utterly annihilated to the thought or imagination.'

Now such as the parts are, such is the whole. If a point be not consider'd as colour'd or tangible, it can convey to us no idea; and consequently the idea of extension, which is compos'd of the ideas of these points, can never possibly exist. But if the idea of extension really can exist, as we are conscious it does, its parts must also exist; and in order to that, must be consider'd as colour'd or tangible. We have therefore no idea of space or extension, but when we regard it as an object either of our sight or feeling.

The same reasoning will prove, that the indivisible moments of time must be fill'd with some real object or existence, whose succession forms the duration, and makes it be conceivable by the mind."

In common with Locke and Eastern Philosophy, Hume considers reflection and sensation to be similar, perhaps identical:

"Thus it appears, that the belief or assent, which always attends the memory and senses, is nothing but the vivacity of those perceptions they present; and that this alone distinguishes them from the imagination. To believe is in this case to feel an immediate impression of the senses, or a repetition of that impression in the memory. 'Tis merely the force and liveliness of the perception, which constitutes the first act of the judgment, and lays the foundation of that reasoning, which we build upon it, when we trace the relation of cause and effect."

Hume considers that the origin of sensation can never be known, believing that the canvass of the mind contains our view of the world whatever the ultimate source of the images within the view and that we can construct consistent bodies of knowledge within these constraints:

"As to those impressions, which arise from the senses, their ultimate cause is, in my opinion, perfectly inexplicable by human reason, and 'twill always be impossible to decide with certainty, whether they arise immediately from the object, or are produc'd by the creative power of the mind, or are deriv'd from the author of our being. Nor is such a question any way material to our present purpose. We may draw inferences from the coherence of our perceptions, whether they be true or false; whether they represent nature justly, or be mere illusions of the senses."

It may be possible to trace the origins of Jackson's Knowledge Argument in Hume's work:

" Suppose therefore a person to have enjoyed his sight for thirty years, and to have become perfectly well acquainted with colours of all kinds, excepting one particular shade of blue, for instance, which it never has been his fortune to meet with. Let all the different shades of that colour, except that single one, be plac'd before him, descending gradually from the deepest to the lightest; 'tis plain, that he will perceive a blank, where that shade is wanting, said will be sensible, that there is a greater distance in that place betwixt the contiguous colours, than in any other. Now I ask, whether 'tis possible for him, from his own imagination, to supply this deficiency, and raise up to himself the idea of that particular shade, tho' it had never been conveyed to him by his senses? I believe i here are few but will be of opinion that he can; and this may serve as a proof, that the simple ideas are not always derived from the correspondent impressions; tho' the instance is so particular and singular, that 'tis scarce worth our observing, and does not merit that for it alone we should alter our general maxim."

David Hume (1748) An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

Hume's view of Locke and Malebranche:

"The fame of Cicero flourishes at present; but that of Aristotle is utterly decayed. La Bruyere passes the seas, and still maintains his reputation: But the glory of Malebranche is confined to his own nation, and to his own age. And Addison, perhaps, will be read with pleasure, when Locke shall be entirely forgotten."

He is clear about relational knowledge in space and time:

"13. .. But though our thought seems to possess this unbounded liberty, we shall find, upon a nearer examination, that it is really confined within very narrow limits, and that all this creative power of the mind amounts to no more than the faculty of compounding, transposing, augmenting, or diminishing the materials afforded us by the senses and experience. When we think of a golden mountain, we only join two consistent ideas, gold, and mountain, with which we were formerly acquainted."

...

19. Though it be too obvious to escape observation, that different ideas are connected together; I do not find that any philosopher has attempted to enumerate or class all the principles of association; a subject, however, that seems worthy of curiosity. To me, there appear to be only three principles of connexion among ideas, namely, Resemblance, Contiguity in time or place, and Cause or Effect."

He is also clear that, although we experience the output of processes, we do not experience the processes themselves:

"29. It must certainly be allowed, that nature has kept us at a great distance from all her secrets, and has afforded us only the knowledge of a few superficial qualities of objects; while she conceals from us those powers and principles on which the influence of those objects entirely depends. Our senses inform us of the colour, weight, and consistence of bread; but neither sense nor reason can ever inform us of those qualities which fit it for the nourishment and support of a human body. Sight or feeling conveys an idea of the actual motion of bodies; but as to that wonderful force or power, which would carry on a moving body for ever in a continued change of place, and which bodies never lose but by communicating it to others; of this we cannot form the most distant conception. ..

58. ... All events seem entirely loose and separate. One event follows another; but we never can observe any tie between them. They seem conjoined, but never connected. And as we can have no idea of any thing which never appeared to our outward sense or inward sentiment, the necessary conclusion seems to be that we have no idea of connexion or power at all, and that these words are absolutely without any meaning, when employed either in philosophical reasonings or common life. "

Our idea of process is not a direct experience but seems to originate from remembering the repetition of events:

"59 ..It appears, then, that this idea of a necessary connexion among events arises from a number of similar instances which occur of the constant conjunction of these events; nor can that idea ever be suggested by any one of these instances, surveyed in all possible lights and positions. But there is nothing in a number of instances, different from every single instance, which is supposed to be exactly similar; except only, that after a repetition of similar instances, the mind is carried by habit, upon the appearance of one event, to expect its usual attendant, and to believe that it will exist."

Emmanuel Kant (1724-1804)

[edit | edit source]

Kant's greatest work on the subject of consciousness and the mind is Critique of Pure Reason (1781). Kant describes his objective in this work as discovering the axioms ("a priori concepts") and then the processes of 'understanding'.

P12 "This enquiry, which is somewhat deeply grounded, has two sides. The one refers to the objects of pure understanding, and is intended to expound and render intelligible the objective validity of its a priori concepts. It is therefore essential to my purposes. The other seeks to investigate the pure understanding itself, its possibility and the cognitive faculties upon which it rests; and so deals with it in its subjective aspect. Although this latter exposition is of great importance for my chief purpose, it does not form an essential part of it. For the chief question is always simply this: - what and how much can the understanding and reason know apart from all experience?"

Kant's idea of perception and mind is summarised in the illustration below:

'Experience' is simply accepted. Kant believes that the physical world exists but is not known directly:

P 24 "For we are brought to the conclusion that we can never transcend the limits of possible experience, though that is precisely what this science is concerned, above all else, to achieve. This situation yields, however, just the very experiment by which, indirectly, we are enabled to prove the truth of this first estimate of our a priori knowledge of reason, namely, that such knowledge has to do only with appearances, and must leave the thing in itself as indeed real per se, but as not known by us. "

Kant is clear about the form and content of conscious experience. He notes that we can only experience things that have appearance and 'form' - content and geometrical arrangement.

P65-66 "IN whatever manner and by whatever means a mode of knowledge may relate to objects, intuition is that through which it is in immediate relation to them, and to which all thought as a means is directed. But intuition takes place only in so far as the object is given to us. This again is only possible, to man at least, in so far as the mind is affected in a certain way. The capacity (receptivity) for receiving representations through the mode in which we are affected by objects, is entitled sensibility. Objects are given to us by means of sensibility, and it alone yields us intuitions; they are thought through the understanding, and from the understanding arise concepts. But all thought must, directly or indirectly, by way of certain characters relate ultimately to intuitions, and therefore, with us, to sensibility, because in no other way can an object be given to us. The effect of an object upon the faculty of representation, so far as we are affected by it, is sensation. That intuition which is in relation to the object through sensation, is entitled empirical. The undetermined object of an empirical intuition is entitled appearance. That in the appearance which corresponds to sensation I term its matter; but that which so determines the manifold of appearance that it allows of being ordered in certain relations, I term the form of appearance. That in which alone the sensations can be posited and ordered in a certain form, cannot itself be sensation; and therefore, while the matter of all appearance is given to us a posteriori only, its form must lie ready for the sensations a priori in the mind, and so must allow of being considered apart from all sensation. "

Furthermore he realises that experience exists without much content. That consciousness depends on form:

P66 "The pure form of sensible intuitions in general, in which all the manifold of intuition is intuited in certain relations, must be found in the mind a priori. This pure form of sensibility may also itself be called pure intuition. Thus, if I take away from the representation of a body that which the understanding thinks in regard to it, substance, force, divisibility, etc. , and likewise what belongs to sensation, impenetrability, hardness, colour, etc. , something still remains over from this empirical intuition, namely, extension and figure. These belong to pure intuition, which, even without any actual object of the senses or of sensation, exists in the mind a priori as a mere form of sensibility. The science of all principles of a priori sensibility I call transcendental aesthetic."

Kant proposes that space exists in our experience and that experience could not exist without it (apodeictic means 'incontrovertible):

P 68 "1. Space is not an empirical concept which has been derived from outer experiences. For in order that certain sensations be referred to something outside me (that is, to something in another region of space from that in which I find myself), and similarly in order that I may be able to represent them as outside and alongside one another, and accordingly as not only different but as in different places, the representation of space must be presupposed. The representation of space cannot, therefore, be empirically obtained from the relations of outer appearance. On the contrary, this outer experience is itself possible at all only through that representation. 2. Space is a necessary a priori representation, which underlies all outer intuitions. We can never represent to ourselves the absence of space, though we can quite well think it as empty of objects. It must therefore be regarded as the condition of the possibility of appearances, and not as a determina- tion dependent upon them. It is an a priori representation, which necessarily underlies outer appearances. * 3. The apodeictic certainty of all geometrical propositions and the possibility of their a priori construction is grounded in this a priori necessity of space. ........."

He is equally clear about the necessity of time as part of experience but he has no clear exposition of the (specious present) extended present:

P 74 "1. Time is not an empirical concept that has been derived from any experience. For neither coexistence nor succession would ever come within our perception, if the representation of time were not presupposed as underlying them a priori. Only on the presupposition of time can we represent to ourselves a number of things as existing at one and the same time (simultaneously) or at different times (successively). They are connected with the appearances only as effects accidentally added by the particular constitution of the sense organs. Accordingly, they are not a priori representations, but are grounded in sensation, and, indeed, in the case of taste, even upon feeling (pleasure and pain), as an effect of sensation. Further, no one can have a priori a representation of a colour or of any taste; whereas, since space concerns only the pure form of intuition, and therefore involves no sensation whatsoever, and nothing empirical, all kinds and determinations of space can and must be represented a priori, if concepts of figures and of their relations are to arise. Through space alone is it possible that things should be outer objects to us. ..2. 3.. 4.. 5..."

Kant has a model of experience as a succession of 3D instants, based on conventional 18th century thinking, allowing his reason to overcome his observation. He says of time that:

P 79 " It is nothing but the form of our inner intuition. If we take away from our inner intuition the peculiar condition of our sensibility, the concept of time likewise vanishes; it does not inhere in the objects, but merely in the subject which intuits them. I can indeed say that my representations follow one another; but this is only to say that we are conscious of them as in a time sequence, that is, in conformity with the form of inner sense. Time is not, therefore, something in itself, nor is it an objective determination inherent in things."

This analysis is strange because if uses the geometric term "form" but then uses the processing term "succession".

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716)

[edit | edit source]

Leibniz is one of the first to notice that there is a problem with the proposition that computational machines could be conscious:

"One is obliged to admit that perception and what depends upon it is inexplicable on mechanical principles, that is, by figures and motions. In imagining that there is a machine whose construction would enable it to think, to sense, and to have perception, one could conceive it enlarged while retaining the same proportions, so that one could enter into it, just like into a windmill. Supposing this, one should, when visiting within it, find only parts pushing one another, and never anything by which to explain a perception. Thus it is in the simple substance, and not in the composite or in the machine, that one must look for perception." Monadology, 17.

Leibniz considered that the world was composed of "monads":

"1. The Monad, of which we shall here speak, is nothing but a simple substance, which enters into compounds. By 'simple' is meant 'without parts.' (Theod. 10.)

2. And there must be simple substances, since there are compounds; for a compound is nothing but a collection or aggregatum of simple things.

3. Now where there are no parts, there can be neither extension nor form [figure] nor divisibility. These Monads are the real atoms of nature and, in a word, the elements of things. " (Monadology 1714).

These monads are considered to be capable of perception through the meeting of things at a point:

"They cannot have shapes, because then they would have parts; and therefore one monad in itself, and at a moment, cannot be distinguished from another except by its internal qualities and actions; which can only be its perceptions (that is, the representations of the composite, or of what is external, in the simple), or its appetitions (its tending to move from one perception to another, that is), which are the principles of change. For the simplicity of a substance does not in any way rule out a multiplicity in the modifications which must exist together in one simple substance; and those modifications must consist in the variety of its relationships to things outside it - like the way in which in a centre, or a point, although it is completely simple, there are an infinity of angles formed which meet in it." (Principles of Nature and Grace 1714).

Leibniz also describes this in his "New System":

"It is only atoms of substance, that is to say real unities absolutely devoid of parts, that can be the sources of actions, and the absolute first principles of the composition of things, and as it were the ultimate elements in the analysis of substances <substantial things>. They might be called metaphysical points; they have something of the nature of life and a kind of perception, and mathematical points are their point of view for expressing the universe."(New System (11) 1695).

Having identified perception with metaphysical points Leibniz realises that there is a problem connecting the points with the world (cf: epiphenomenalism):

"Having decided these things, I thought I had reached port, but when I set myself to think about the union of the soul with the body I was as it were carried back into the open sea. For I could find no way of explaining how the body can make something pass over into the soul or vice versa, or how one created substance can communicate with another."(New System (12) 1695).

Leibniz devises a theory of "pre-established harmony" to overcome this epiphenomenalism. He discusses how two separate clocks could come to tell the same time and proposes that this could be due to mutual influence of one clock on the other ("the way of influence"), continual adjustment by a workman ("the way of assistance") or by making the clocks so well that they are always in agreement ("the way of pre-established agreement" or harmony). He considers each of these alternatives for harmonising the perceptions with the world and concludes that only the third is viable:

"Thus there remains only my theory, the way of pre-established harmony, set up by a contrivance of divine foreknowledge, which formed each of these substances from the outset in so perfect, so regular, and so exact a manner, that merely by following out its own laws, which were given to it when it was brought into being, each substance is nevertheless in harmony with the other, just as if there were a mutual influence between them, or as if in addition to his general concurrence God were continually operating upon them. (Third Explanation of the New System (5), 1696)."

This means that he must explain how perceptions involving the world take place:

"Because of the plenitude of the world everything is linked, and every body acts to a greater or lesser extent on every other body in proportion to distance, and is affected by it in return. It therefore follows that every monad is a living mirror, or a mirror endowed with internal activity, representing the universe in accordance with its own point of view, and as orderly as the universe itself. The perceptions of monads arise one out of another by the laws of appetite, or of the final causes of good and evil (which are prominent perceptions, orderly or disorderly), just as changes in bodies or in external phenomena arise one from another by the laws of efficient causes, of motion that is. Thus there is perfect harmony between the perceptions of the monad and the motions of bodies, pre-established from the outset, between the system of efficient causes and that of final causes. And it is that harmony that the agreement or physical union between the soul and body consists, without either of them being able to change the laws of the other." (Principles of Nature and Grace (3) 1714).

The "laws of appetite" are defined as:

"The action of the internal principle which brings about change, or the passage from one perception to another, can be called appetition. In fact appetite cannot always attain in its entirety the whole of the perception towards which it tends, but it always obtains some part of it, and attains new perceptions. Monadology 15.

Leibniz thought animals had souls but not minds:

"But true reasoning depends on necessary or eternal truths like those of logic, numbers, and geometry, which make indubitable connections between ideas, and conclusions which are inevitable. Animals in which such conclusions are never perceived are called brutes; but those which recognise such necessary truths are what are rightly called rational animals and their souls are called minds. (Principles of Nature and Grace (5) 1714).

Minds allow reflection and awareness:

"And it is by the knowledge of necessary truths, and by the abstractions they involve, that we are raised to acts of reflection, which make us aware of what we call myself, and make us think of this or that thing as in ourselves. And in this way, by thinking of ourselves, we think of being, of substance, of simples and composites, of the immaterial - and, by realising that what is limited in us is limitless in him, of God himself. And so these acts of reflection provide the principle objects of our reasonings." Monadology, 30.

George Berkeley (1685 - 1753)

[edit | edit source]A Treatise on the Principles of Human Knowledge. 1710

Berkeley introduces the Principles of Human Knowledge with a diatribe against abstract ideas. He uses the abstract ideas of animals as an example:

"Introduction. 9........The constituent parts of the abstract idea of animal are body, life, sense, and spontaneous motion. By body is meant body without any particular shape or figure, there being no one shape or figure common to all animals, without covering, either of hair, or feathers, or scales, &c., nor yet naked: hair, feathers, scales, and nakedness being the distinguishing properties of particular animals, and for that reason left out of the abstract idea. Upon the same account the spontaneous motion must be neither walking, nor flying, nor creeping; it is nevertheless a motion, but what that motion is it is not easy to conceive.

He then declares that such abstractions cannot be imagined. He emphasises that ideas are "represented to myself" and have shape and colour:

"Introduction. 10. Whether others have this wonderful faculty of abstracting their ideas, they best can tell: for myself, I find indeed I have a faculty of imagining, or representing to myself, the ideas of those particular things I have perceived, and of variously compounding and dividing them. I can imagine a man with two heads, or the upper parts of a man joined to the body of a horse. I can consider the hand, the eye, the nose, each by itself abstracted or separated from the rest of the body. But then whatever hand or eye I imagine, it must have some particular shape and colour. Likewise the idea of man that I frame to myself must be either of a white, or a black, or a tawny, a straight, or a crooked, a tall, or a low, or a middle-sized man. I cannot by any effort of thought conceive the abstract idea above described. And it is equally impossible for me to form the abstract idea of motion distinct from the body moving, and which is neither swift nor slow, curvilinear nor rectilinear; and the like may be said of all other abstract general ideas whatsoever."

This concept of ideas as extended things, or representations, is typical of the usage amongst philosophers in the 17th and 18th century and can cause confusion in modern readers. Berkeley considers that words that are used to describe classes of things in the abstract can only be conceived as particular cases:

"Introduction. 15... Thus, when I demonstrate any proposition concerning triangles, it is to be supposed that I have in view the universal idea of a triangle; which ought not to be understood as if I could frame an idea of a triangle which was neither equilateral, nor scalenon, nor equicrural; but only that the particular triangle I consider, whether of this or that sort it matters not, doth equally stand for and represent all rectilinear triangles whatsoever, and is in that sense universal. All which seems very plain and not to include any difficulty in it.

Intriguingly, he considers that language is used to directly excite emotions as well as to communicate ideas:

"Introduction. 20. ... I entreat the reader to reflect with himself, and see if it doth not often happen, either in hearing or reading a discourse, that the passions of fear, love, hatred, admiration, disdain, and the like, arise immediately in his mind upon the perception of certain words, without any ideas coming between.

Berkeley considers that extension is a quality of mind:

"11. Again, great and small, swift and slow, are allowed to exist nowhere without the mind, being entirely relative, and changing as the frame or position of the organs of sense varies. The extension therefore which exists without the mind is neither great nor small, the motion neither swift nor slow, that is, they are nothing at all. But, say you, they are extension in general, and motion in general: thus we see how much the tenet of extended movable substances existing without the mind depends on the strange doctrine of abstract ideas."

He notes that the rate at which things pass may be related to the mind:

"14..... Is it not as reasonable to say that motion is not without the mind, since if the succession of ideas in the mind become swifter, the motion, it is acknowledged, shall appear slower without any alteration in any external object?

Berkeley raises the issue of whether objects exist without being perceived. He bases his argument on the concept of perception being the perceiving of "our own ideas or sensations":

"4. It is indeed an opinion strangely prevailing amongst men, that houses, mountains, rivers, and in a word all sensible objects, have an existence, natural or real, distinct from their being perceived by the understanding. But, with how great an assurance and acquiescence soever this principle may be entertained in the world, yet whoever shall find in his heart to call it in question may, if I mistake not, perceive it to involve a manifest contradiction. For, what are the fore-mentioned objects but the things we perceive by sense? and what do we perceive besides our own ideas or sensations? and is it not plainly repugnant that any one of these, or any combination of them, should exist unperceived?"

He further explains this concept in terms of some Eternal Spirit allowing continued existence. Berkeley is clear that the contents of the mind have "colour, figure, motion, smell, taste etc.":

"7. From what has been said it follows there is not any other Substance than Spirit, or that which perceives. But, for the fuller proof of this point, let it be considered the sensible qualities are colour, figure, motion, smell, taste, etc., i.e. the ideas perceived by sense. Now, for an idea to exist in an unperceiving thing is a manifest contradiction, for to have an idea is all one as to perceive; that therefore wherein colour, figure, and the like qualities exist must perceive them; hence it is clear there can be no unthinking substance or substratum of those ideas."

He elaborates the concept that there is no unthinking substance or substratum for ideas and all is mind:

"18. But, though it were possible that solid, figured, movable substances may exist without the mind, corresponding to the ideas we have of bodies, yet how is it possible for us to know this? Either we must know it by sense or by reason. As for our senses, by them we have the knowledge only of our sensations, ideas, or those things that are immediately perceived by sense, call them what you will: but they do not inform us that things exist without the mind, or unperceived, like to those which are perceived. This the materialists themselves acknowledge. It remains therefore that if we have any knowledge at all of external things, it must be by reason, inferring their existence from what is immediately perceived by sense. But what reason can induce us to believe the existence of bodies without the mind, from what we perceive, since the very patrons of Matter themselves do not pretend there is any necessary connexion betwixt them and our ideas? I say it is granted on all hands (and what happens in dreams, phrensies, and the like, puts it beyond dispute) that it is possible we might be affected with all the ideas we have now, though there were no bodies existing without resembling them. Hence, it is evident the supposition of external bodies is not necessary for the producing our ideas; since it is granted they are produced sometimes, and might possibly be produced always in the same order, we see them in at present, without their concurrence. "

and stresses that there is no apparent connection between mind and the proposed material substrate of ideas:

"19. But, though we might possibly have all our sensations without them, yet perhaps it may be thought easier to conceive and explain the manner of their production, by supposing external bodies in their likeness rather than otherwise; and so it might be at least probable there are such things as bodies that excite their ideas in our minds. But neither can this be said; for, though we give the materialists their external bodies, they by their own confession are never the nearer knowing how our ideas are produced; since they own themselves unable to comprehend in what manner body can act upon spirit, or how it is possible it should imprint any idea in the mind. .....

Berkeley makes a crucial observation, that had also been noticed by Descartes, that ideas are passive:

"25. All our ideas, sensations, notions, or the things which we perceive, by whatsoever names they may be distinguished, are visibly inactive- there is nothing of power or agency included in them. So that one idea or object of thought cannot produce or make any alteration in another. To be satisfied of the truth of this, there is nothing else requisite but a bare observation of our ideas. For, since they and every part of them exist only in the mind, it follows that there is nothing in them but what is perceived: but whoever shall attend to his ideas, whether of sense or reflexion, will not perceive in them any power or activity; there is, therefore, no such thing contained in them. A little attention will discover to us that the very being of an idea implies passiveness and inertness in it, insomuch that it is impossible for an idea to do anything, or, strictly speaking, to be the cause of anything: neither can it be the resemblance or pattern of any active being, as is evident from sect. 8. Whence it plainly follows that extension, figure, and motion cannot be the cause of our sensations. To say, therefore, that these are the effects of powers resulting from the configuration, number, motion, and size of corpuscles, must certainly be false.

He considers that "the cause of ideas is an incorporeal active substance or Spirit (26)".

He summarises the concept of an Eternal Spirit that governs real things and a representational mind that copies the form of the world as follows:

"33. The ideas imprinted on the Senses by the Author of nature are called real things; and those excited in the imagination being less regular, vivid, and constant, are more properly termed ideas, or images of things, which they copy and represent. But then our sensations, be they never so vivid and distinct, are nevertheless ideas, that is, they exist in the mind, or are perceived by it, as truly as the ideas of its own framing. The ideas of Sense are allowed to have more reality in them, that is, to be more strong, orderly, and coherent than the creatures of the mind; but this is no argument that they exist without the mind. They are also less dependent on the spirit, or thinking substance which perceives them, in that they are excited by the will of another and more powerful spirit; yet still they are ideas, and certainly no idea, whether faint or strong, can exist otherwise than in a mind perceiving it.

Berkeley considers that the concept of distance is a concept in the mind and also that dreams can be compared directly with sensations:

"42. Thirdly, it will be objected that we see things actually without or at distance from us, and which consequently do not exist in the mind; it being absurd that those things which are seen at the distance of several miles should be as near to us as our own thoughts. In answer to this, I desire it may be considered that in a dream we do oft perceive things as existing at a great distance off, and yet for all that, those things are acknowledged to have their existence only in the mind."

He considers that ideas can be extended without the mind being extended:

"49. Fifthly, it may perhaps be objected that if extension and figure exist only in the mind, it follows that the mind is extended and figured; since extension is a mode or attribute which (to speak with the schools) is predicated of the subject in which it exists. I answer, those qualities are in the mind only as they are perceived by it- that is, not by way of mode or attribute, but only by way of idea; and it no more follows the soul or mind is extended, because extension exists in it alone, than it does that it is red or blue, because those colours are on all hands acknowledged to exist in it, and nowhere else. As to what philosophers say of subject and mode, that seems very groundless and unintelligible. For instance, in this proposition "a die is hard, extended, and square," they will have it that the word die denotes a subject or substance, distinct from the hardness, extension, and figure which are predicated of it, and in which they exist. This I cannot comprehend: to me a die seems to be nothing distinct from those things which are termed its modes or accidents. And, to say a die is hard, extended, and square is not to attribute those qualities to a subject distinct from and supporting them, but only an explication of the meaning of the word die.

Berkeley proposes that time is related to the succession of ideas:

"98. For my own part, whenever I attempt to frame a simple idea of time, abstracted from the succession of ideas in my mind, which flows uniformly and is participated by all beings, I am lost and embrangled in inextricable difficulties. I have no notion of it at all, only I hear others say it is infinitely divisible, and speak of it in such a manner as leads me to entertain odd thoughts of my existence; since that doctrine lays one under an absolute necessity of thinking, either that he passes away innumerable ages without a thought, or else that he is annihilated every moment of his life, both which seem equally absurd. Time therefore being nothing, abstracted from the succession of ideas in our minds, it follows that the duration of any finite spirit must be estimated by the number of ideas or actions succeeding each other in that same spirit or mind. Hence, it is a plain consequence that the soul always thinks; and in truth whoever shall go about to divide in his thoughts, or abstract the existence of a spirit from its cogitation, will, I believe, find it no easy task.

"99. So likewise when we attempt to abstract extension and motion from all other qualities, and consider them by themselves, we presently lose sight of them, and run into great extravagances. All which depend on a twofold abstraction; first, it is supposed that extension, for example, may be abstracted from all other sensible qualities; and secondly, that the entity of extension may be abstracted from its being perceived. But, whoever shall reflect, and take care to understand what he says, will, if I mistake not, acknowledge that all sensible qualities are alike sensations and alike real; that where the extension is, there is the colour, too, i.e., in his mind, and that their archetypes can exist only in some other mind; and that the objects of sense are nothing but those sensations combined, blended, or (if one may so speak) concreted together; none of all which can be supposed to exist unperceived."

He regards "spirit" as something separate from ideas and attempts to answer the charge that as spirit is not an idea it cannot be known:

"139. But it will be objected that, if there is no idea signified by the terms soul, spirit, and substance, they are wholly insignificant, or have no meaning in them. I answer, those words do mean or signify a real thing, which is neither an idea nor like an idea, but that which perceives ideas, and wills, and reasons about them. ....

Thomas Reid (1710-1796)

[edit | edit source]

Thomas Reid is generally regarded as the founder of Direct Realism. Reid was a Presbyterian minister for the living of Newmachar near Aberdeen from 1737. He is explicit about the 'directness' of his realism:

"It is therefore acknowledged by this philosopher to be a natural instinct or prepossession, a universal and primary opinion of all men, a primary instinct of nature, that the objects which we immediately perceive by our senses are not images in our minds, but external objects, and that their existence is independent of us and our perception. (Thomas Reid Essays, 14)"

In common with Descartes and Malebranche, Reid considers that the mind itself is an unextended thing:

".. I take it for granted, upon the testimony of common sense, that my mind is a substance-that is, a permanent subject of thought; and my reason convinces me that it is an unextended and invisible substance; and hence I infer that there cannot be in it anything that resembles extension (Inquiry)".

Reid is also anxious to equate the unextended mind with the soul:

"The soul, without being present to the images of the things perceived, could not possibly perceive them. A living substance can only there perceive, where it is present, either to the things themselves, (as the omnipresent God is to the whole universe,) or to the images of things, as the soul is in its proper sensorium."

Reid's Direct Realism is therefore the idea that the physical objects in the world are in some way presented directly to a soul. This approach is known as "Natural Dualism".

Reid's views show his knowledge of Aristotle's ideas:

"When we perceive an object by our senses, there is, first, some impression made by the object upon the organ of sense, either immediately, or by means of some medium. By this, an impression is made upon the brain, in consequence of which we feel some sensation. " (Reid 1785)

He differs from Aristotle because he believes that the content of phenomenal consciousness is things in themselves, not signals derived from things in the brain. However, he has no idea how such a phenomenon could occur:

"How a sensation should instantly make us conceive and believe the existence of an external thing altogether unlike it, I do not pretend to know; and when I say that the one suggests the other, I mean not to explain the manner of their connection, but to express a fact, which everyone may be conscious of namely, that, by a law of our nature, such a conception and belief constantly and immediately follow the sensation." (Reid 1764).

Reid's idea of mind is almost impossible to illustrate because it lacks sufficient physical definition. It is like naive realism but without any communication by light between object and observer. Reid was largely ignored until the rise of modern Direct Realism.

Reading between the lines, it seems that Reid is voicing the ancient intuition that the observer and the content of an observation are directly connected in some way. As will be seen later, this intuition cannot distinguish between a direct connection with the world itself and a direct connection with signals from the world beyond the body that are formed into a virtual reality in the brain.

References

[edit | edit source]- Descartes, R. (1628). Rules For The Direction of The Mind.

- Descartes, R. (1637). DISCOURSE ON THE METHOD OF RIGHTLY CONDUCTING THE REASON, AND SEEKING TRUTH IN THE SCIENCES.

- Descartes, R. (1641). Meditations on First Philosophy.

- Descartes, R. (1664) "Treatise on Man". Translated by John Cottingham, et al. The Philosophical Writings of Descartes, Vol. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985) 99-108.

- Kant, I. (1781) Critique of Pure Reason. Trans. Norman Kemp Smith with preface by Howard Caygill. Pub: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Locke, J. (1689). An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

- Reid, T. (1785). Essays on the Intellectual Powers of Man. Edited by Brookes, Derek. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2002.

- Reid, T. (1764). An Inquiry into the Human Mind on the Principles of Common Sense. Edited by Brookes, Derek. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1997.

- Russell, B. (1945). A History of Western Philosophy. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Further Reading

See: "Thomas Reid" at Wikisource

- Cartesian Conscientia by Robert Hennig