Consciousness Studies/Early Ideas

This section is an academic review of major contributions to consciousness studies. Readers who are interested in the current philosophy of consciousness will find this in Part II and readers interested in the neuroscience of consciousness should refer to Part III.

Vedic Sciences are present the first known ideas related to consciousness, dating back to at least 1500 years ago according to The British Library. The ten books of Rig Veda, which are attributed to the end of the Bronze period, which are on of the ten oldest living texts of the world, illuminates us on ultimate or supreme consciousness. In the Rig Veda (R.V. IV. XL. 5) Nrishad is the dweller amongst humans; Nrishad is explained as Chaitanya or 'Consciousness' or Prana or 'vitality' because both dwell in humans.

In his commentary on the Isha Upanishad,[5] Sri Aurobindo explains that the Atman, the Self manifests through a seven-fold movement of Prakrti. These seven folds of consciousness, along with their dominant principles are:[6]

annamaya puruṣa - physical prāṇamaya puruṣa - nervous / vital manomaya puruṣa - mental / mind vijñānamaya puruṣa - knowledge and truth ānandamaya puruṣa - Aurobindo's concept of Delight, otherwise known as Bliss caitanya puruṣa - infinite divine self-awareness[7] sat puruṣa - state of pure divine existence

The first five of these are arranged according to the specification of the panchakosha from the second chapter of the Taittiriya Upanishad. The final three elements make up satcitananda, with cit being referred to as chaitanya.

The essential nature of Brahman as revealed in deep sleep and Yoga is Chaitanya (pure consciousness).[8]

The earliest use of the word soul or Ātman in Indian texts is also found in the Rig Veda (c. 1500 BC)(RV X.97.11).[20] Yāska, the ancient Indian grammarian, commenting on this Rigvedic verse, accepts the following meanings of Ātman: the pervading principle, the organism in which other elements are united and the ultimate sentient principle.[21]

Other hymns of Rig Veda where the word Ātman appears include I.115.1, VII.87.2, VII.101.6, VIII.3.24, IX.2.10, IX.6.8, and X.168.4.[22]

The Rig Veda takes one from before creation, through creation of the world, to creation of self, and ends with the creation of creation itself, after which creation of the universe came. Upon close reading, one can trace the various stages of consciousness to the material world, from absolute truth or Sat to absolute material or Asat, two recurring concepts that run through the entire Rig Veda.

The Greeks had no exact equivalent for the term 'consciousness', which has a wide range of meanings in modern usage, but in the thinkers below we find an analysis of phenomenal consciousness and the source of many ideas developed by later Socratics, especially the Stoics, and by Christian thinkers like Augustine.

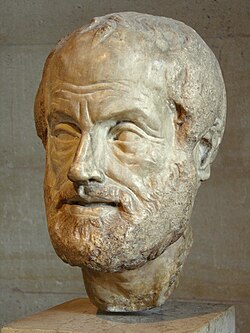

Aristotle (c. 350 BC) On the Soul

[edit | edit source](De Anima) http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Aristotle/De-anima/

Aristotle, perhaps more than any other ancient Greek philosopher, set the terms of reference for the future discussion of the problem of consciousness. His idea of the mind is summarised in the illustration below.

Aristotle was a physicalist, believing that things are embodied in the material universe:

"... That is precisely why the study of the soul [psyche] must fall within the science of Nature, at least so far as in its affections it manifests this double character. Hence a physicist would define an affection of soul differently from a dialectician; the latter would define e.g. anger as the appetite for returning pain for pain, or something like that, while the former would define it as a boiling of the blood or warm substance surround the heart. The latter assigns the material conditions, the former the form or formulable essence; for what he states is the formulable essence of the fact, though for its actual existence there must be embodiment of it in a material such as is described by the other."(Book I, 403a)

The works of Aristotle provide our first clear account of the concept of signals and information. He was aware that an event can change the state of matter and this change of state can be transmitted to other locations where it can further change a state of matter:

"If what has colour is placed in immediate contact with the eye, it cannot be seen. Colour sets in movement not the sense organ but what is transparent, e.g. the air, and that, extending continuously from the object to the organ, sets the latter in movement. Democritus misrepresents the facts when he expresses the opinion that if the interspace were empty one could distinctly see an ant on the vault of the sky; that is an impossibility. Seeing is due to an affection or change of what has the perceptive faculty, and it cannot be affected by the seen colour itself; it remains that it must be affected by what comes between. Hence it is indispensable that there be something in between-if there were nothing, so far from seeing with greater distinctness, we should see nothing at all." (Book II, 419a])

He was also clear about the relationship of information to 'state':

"By a 'sense' is meant what has the power of receiving into itself the sensible forms of things without the matter. This must be conceived of as taking place in the way in which a piece of wax takes on the impress of a signet-ring without the iron or gold; we say that what produces the impression is a signet of bronze or gold, but its particular metallic constitution makes no difference: in a similar way the sense is affected by what is coloured or flavoured or sounding, but it is indifferent what in each case the substance is; what alone matters is what quality it has, i.e. in what ratio its constituents are combined"(Book II, 424a)

Aristotle also mentioned the problem of the simultaneity of experience. The explanation predates Galilean and modern physics so lacks our modern language to explain how many things could be at a point and an instant:

"... just as what is called a 'point' is, as being at once one and two, properly said to be divisible, so here, that which discriminates is qua undivided one, and active in a single moment of time, while so far forth as it is divisible it twice over uses the same dot at one and the same time. So far forth then as it takes the limit as two' it discriminates two separate objects with what in a sense is divided: while so far as it takes it as one, it does so with what is one and occupies in its activity a single moment of time. (Book III, 427a)

He described the problem of recursion that would occur if the mind were due to the flow of material things in space:

"...mind is either without parts or is continuous in some other way than that which characterizes a spatial magnitude. How, indeed, if it were a spatial magnitude, could mind possibly think? Will it think with any one indifferently of its parts? In this case, the 'part' must be understood either in the sense of a spatial magnitude or in the sense of a point (if a point can be called a part of a spatial magnitude). If we accept the latter alternative, the points being infinite in number, obviously the mind can never exhaustively traverse them; if the former, the mind must think the same thing over and over again, indeed an infinite number of times (whereas it is manifestly possible to think a thing once only)."(Book I, 407a)

Aristotle explicitly mentions the regress:

"..we must fall into an infinite regress or we must assume a sense which is aware of itself." (Book III,425b)

However, this regress was not as problematic for Aristotle as it is for philosophers who are steeped in nineteenth century ideas. Aristotle was a physicalist who was not burdened with materialism and so was able to escape from the idea that the only possibility for the mind is a flow of material from place to place over a succession of disconnected instants. He was able to propose that subjects and objects are part of the same thing, he notes that thought is both temporally and spatially extended:

"But that which mind thinks and the time in which it thinks are in this case divisible only incidentally and not as such. For in them too there is something indivisible (though, it may be, not isolable) which gives unity to the time and the whole of length; and this is found equally in every continuum whether temporal or spatial." (Book III,430b)

This idea of time allowed him to identify thinking with the object of thought, there being no need to cycle thoughts from instant to instant because mental time is extended:

"In every case the mind which is actively thinking is the objects which it thinks."

He considered imagination to be a disturbance of the sense organs:

"And because imaginations remain in the organs of sense and resemble sensations, animals in their actions are largely guided by them, some (i.e. the brutes) because of the non-existence in them of mind, others (i.e. men) because of the temporary eclipse in them of mind by feeling or disease or sleep.(Book III, 429a)"

And considered that all thought occurs as images:

"To the thinking soul images serve as if they were contents of perception (and when it asserts or denies them to be good or bad it avoids or pursues them). That is why the soul never thinks without an image."(Book III, ).

Aristotle also described the debate between the cognitive and behaviourist approaches with their overtones of the conflict between modern physicalism and pre twentieth century materialism:

"Some thinkers, accepting both premisses, viz. that the soul is both originative of movement and cognitive, have compounded it of both and declared the soul to be a self-moving number."(Book I, 404b)

The idea of a 'self-moving number' is not as absurd as it seems, like much of Ancient Greek philosophy.

Aristotle was also clear about there being two forms involved in perception. He proposed that the form and properties of the things that are directly in the mind are incontrovertible but that our inferences about the form and properties of the things in the world that give rise to the things in the mind can be false:

"Perception (1) of the special objects of sense is never in error or admits the least possible amount of falsehood. (2) That of the concomitance of the objects concomitant with the sensible qualities comes next: in this case certainly we may be deceived; for while the perception that there is white before us cannot be false, the perception that what is white is this or that may be false. (3) Third comes the perception of the universal attributes which accompany the concomitant objects to which the special sensibles attach (I mean e.g. of movement and magnitude); it is in respect of these that the greatest amount of sense-illusion is possible."(Book III, 428b)

Imagination, according to this model, lays out things in the senses.

Galen

[edit | edit source]The 'physicians' (most especially Galen) incorporated ideas from the Hippocractics and from Plato into a view in which 3 (or more) inner senses—most basically memory, estimation, and imagination—were associated with 3 ventricles in the brain.

This is a stub that needs further expansion.

Homer (c. 800-900 BC) The Iliad and Odyssey

[edit | edit source]

Panpsychism and panexperientialism can be traced to, at least, Homer's Iliad. Just reading the book allows us to experience what a different focus of consciousness feels like. It is a way of being, being a Homeric Greek, thus distinct from being a modern man. Both states of consciousness result in different ways of experiencing the world.

As we read the Iliad, we are drawn into the book through the images it creates in us and the feelings it evokes in us through the meter and the language. The reader becomes the book. "The reader became the book, and the summer night was like the conscious being of the book" (Wallace Stevens). That experience of becoming the book, of losing yourself in the book, is the experience of a different aspect of consciousness, being a Homeric Greek.

Homer frequently ascribes even our emotions to the world around us. The ancients do not just fear but fear grips them, for example: "So spake Athene, and pale fear gat hold of them all. The arms flew from their hands in their terror and fell all upon the ground, as the goddess uttered her voice" (Odyssey book XXIV).

The German classicist Bruno Snell, in The Discovery of the Mind provides us with "a convincing account of the enormous change in ... human personality which took place during the centuries covered by Homer (to) Socrates."(The London Times Literary Supplement). Snell's book establishes two distinct aspects of consciousness. He says, "The experience of Homer differs from our own" (p.v); "For Homer, psyche is the force which keeps the human being alive..."(p. 8). When the psyche leaves, the owner loses consciousness. The Homeric psyche is where pan-psychism originates. It begins in a conception of consciousness as a force that is separate from the body. Snell compares Homer to the tragedy of Orestes, which focuses on the individual. "Homer concentrates on the action (process) and the situation in preference to the agent..."(p. 211) Orestes is in a different state of consciousness, "a new state of consciousness"(p. 211).

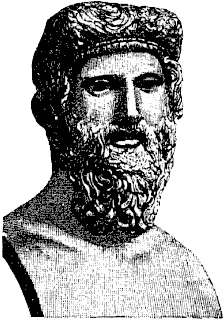

Plato (427-347 BC)

[edit | edit source]The Republic http://www.constitution.org/pla/repub_00.htm Especially book VI http://www.constitution.org/pla/repub_06.htm and book VII (the Cave) http://www.constitution.org/pla/repub_07.htm

Plato's most interesting contributions to consciousness studies are in book VI of The Republic. His idea of the mind is illustrated below.

He believes that light activates pre-existing capabilities in the eyes:

"Sight being, as I conceive, in the eyes, and he who has eyes wanting to see; color being also present in them, still unless there be a third nature specially adapted to the purpose, the owner of the eyes will see nothing and the colors will be invisible."

However, it is in the metaphor of the divided line that Plato introduces a fascinating account of the relationships and properties of things. He points out that analysis deals in terms of the relationships of pure forms:

"And do you not know also that although they make use of the visible forms and reason about them, they are thinking not of these, but of the ideals which they resemble; not of the figures which they draw, but of the absolute square and the absolute diameter, and so on -- the forms which they draw or make, and which have shadows and reflections in water of their own, are converted by them into images, but they are really seeking to behold the things themselves, which can only be seen with the eye of the mind?"

Notice how he introduces the notion of a mind's eye observing mental content arranged as geometrical forms. He proposes that through this mode of ideas we gain understanding:

"And the habit which is concerned with geometry and the cognate sciences I suppose that you would term understanding, and not reason, as being intermediate between opinion and reason."

However, the understanding can also contemplate knowledge:

"..I understand you to say that knowledge and being, which the science of dialectic contemplates, are clearer than the notions of the arts, as they are termed, which proceed from hypotheses only: these are also contemplated by the understanding, and not by the senses: yet, because they start from hypotheses and do not ascend to a principle, those who contemplate them appear to you not to exercise the higher reason upon them, although when a first principle is added to them they are cognizable by the higher reason. "

Plato's work is not usually discussed in this way but is extended to universals such as the idea of the colour red as a universal that can be applied to many specific instances of things.

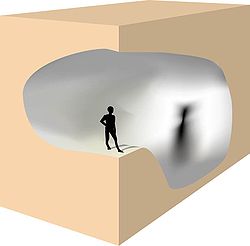

In "Plato's Cave" (Book VII) Plato describes how experience could be some transfer from or copy of real things rather than the things themselves:

"And now, I said, let me show in a figure how far our nature is enlightened or unenlightened: — Behold! human beings living in a underground den, which has a mouth open towards the light and reaching all along the den; here they have been from their childhood, and have their legs and necks chained so that they cannot move, and can only see before them, being prevented by the chains from turning round their heads. Above and behind them a fire is blazing at a distance, and between the fire and the prisoners there is a raised way; and you will see, if you look, a low wall built along the way, like the screen which marionette players have in front of them, over which they show the puppets.

I see.

And do you see, I said, men passing along the wall carrying all sorts of vessels, and statues and figures of animals made of wood and stone and various materials, which appear over the wall? Some of them are talking, others silent.

You have shown me a strange image, and they are strange prisoners.

Like ourselves, I replied; and they see only their own shadows, or the shadows of one another, which the fire throws on the opposite wall of the cave?

True, he said; how could they see anything but the shadows if they were never allowed to move their heads?

And of the objects which are being carried in like manner they would only see the shadows?

Yes, he said.

And if they were able to converse with one another, would they not suppose that they were naming what was actually before them?

Very true.

And suppose further that the prison had an echo which came from the other side, would they not be sure to fancy when one of the passers-by spoke that the voice which they heard came from the passing shadow?

No question, he replied.

To them, I said, the truth would be literally nothing but the shadows of the images.

That is certain.

And now look again, and see what will naturally follow it, the prisoners are released and disabused of their error. At first, when any of them is liberated and compelled suddenly to stand up and turn his neck round and walk and look towards the light, he will suffer sharp pains; the glare will distress him, and he will be unable to see the realities of which in his former state he had seen the shadows; and then conceive some one saying to him, that what he saw before was an illusion, but that now, when he is approaching nearer to being and his eye is turned towards more real existence, he has a clearer vision, — what will be his reply? And you may further imagine that his instructor is pointing to the objects as they pass and requiring him to name them, — will he not be perplexed? Will he not fancy that the shadows which he formerly saw are truer than the objects which are now shown to him?"

This early intuition of information theory predates Aristotle's concept of the transfer of states from one place to another.

Parmenides (c. 480 BC) On Nature

[edit | edit source]Siddhartha Gautama (c. 500 BC) Buddhist Texts

[edit | edit source]

Siddhartha Gautama was born about 563BC. He became known as 'Buddha' ('the awakened one') from the age of about thirty five. Buddha handed down a way of life that might lead, eventually, to an enlightened state called Nirvana. In the three centuries after his death Buddhism split into two factions, the Mahayana (greater raft or vehicle) and the Theravada (the way of the elders). The Mahayana use the slightly derogatory term Hinayana (lesser raft or vehicle) for Theravada Buddhism. Mahayana Buddhism gave rise to other sects such as Zen Buddhism in Japan and Vajrayana Buddhism in Tibet. Mahayana Buddhism is more like a religion, complete with god like entities whereas Theravada Buddhism is more like a philosophy.

Theravada Buddhist meditation is described in books called the Pali Canon which contains the 'Vinayas' that describe monastic life, the 'Suttas' which are the central teachings of Theravada Buddhism and the 'Abhidhamma' which is an analysis of the other two parts or 'pitakas'. Two meditational systems are described: the development of serenity (samathabhavana) and the development of insight (vipassanabhavana). The two systems are complementary, serenity meditation providing a steady foundation for the development of insight. As meditation proceeds the practitioner passes through a series of stages called 'jhanas'. There are four of these stages of meditation and then a final stage known as the stage of the 'immaterial jhanas'.

The Jhanas

The first jhana is a stage of preparation where the meditator rids themselves of the hindrances (sensual desire, ill will, sloth and torpor, restlessness and worry, and doubt). This is best achieved by seclusion. During the process of getting rid of the hindrances the meditator develops the five factors: applied thought, sustained thought, rapture, happiness and one-pointedness of mind. This is done by concentrating on a practice object until it can be easily visualised. Eventually the meditator experiences a luminous replica of the object called the counterpart sign (patibhaganimitta).

Applied thought involves examining, visualising and thinking about the object. Sustained thought involves always returning to the object, not drifting away from it. Rapture involves a oneness with the object and is an ecstacy that helps absorption with and in the object. Happiness is the feeling of happiness that everyone has when something good happens (unlike rapture, which is a oneness with the object of contemplation). One-pointedness of mind is the ability to focus on a single thing without being distracted.

The second jhana involves attaining the first without effort, there is no need for applied or sustained thought, only rapture, happiness and one-pointedness of mind remain. The second jhana is achieved by contemplating the first jhana. The second jhana is a stage of effortless concentration.

The third jhana involves mindfulness and discernment. The mindfulness allows an object of meditation to be held effortlessly in the mind. The discernment consists of discerning the nature of the object without delusion and hence avoiding rapture.

In the fourth jhana mindfulness is maintained but the delusion of happiness is contemplated. Eventually mindfulness remains without pleasure or pain. In the fourth jhana the meditator achieves "purity of mindfulness due to equanimity" (upekkhasatiparisuddhi).

The Immaterial Jhanas

The first four jhanas will be familiar from earlier, Hindu meditational techniques. Once the fourth jhana has been achieved the meditator can embark on the immaterial jhanas. There are four immaterial jhanas: the base of boundless space, the base of boundless consciousness, the base of nothingness, and the base of neither-perception-nor-non-perception.

The base of boundless space is achieved by meditating on the absence of the meditation object. It is realised that the space occupied by the object is boundless and that the mind too is boundless space. The base of boundless consciousness involves a realisation that the boundless space is boundless consciousness. The base of nothingness is a realisation that the present does not exist, the meditator should "give attention to the present non-existence, voidness, secluded aspect of that same past consciousness belonging to the base consisting of boundless space" (Gunaratana 1988). The base of neither-perception-nor-non-perception is a realisation that nothing is perceived in the void.

In Theravada Buddhism the attainment of the fourth jhana and its immaterial jhanas represents a mastery of serenity meditation. This is a foundation for insight meditation.

Buddhism is very practical and eschews delusions. It is realised that serenity meditation is a state of mind, a steady foundation that might, nowadays be called a physiological state. It is through insight meditation where the practitioner becomes a philosopher that enlightenment is obtained.

Further reading

The Buddhist Publication Society. Especially: The Jhanas In Theravada Buddhist Meditation by Henepola Gunaratana. The Wheel Publication No. 351/353 ISBN 955-24-0035-X. 1988 Buddhist Publication Society. http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/bps/index.html