American Revolution/The British Attack New York

Washington moves to New York

[edit | edit source]When Washington heard that the British were going to attack New York, he took the Army, and stationed it in present day New York City.

The British Mass Troops

[edit | edit source]General Sir William Howe, with the services of his brother, Admiral Lord Howe, began amassing troops on Staten Island in July 1776. General Washington, with a smaller army of about 19,000 men, was uncertain where the Howes intended to strike. He unwittingly violated a cardinal rule of warfare and divided his troops about equally in the face of a stronger opponent. The Continental Army was split between Long Island and Manhattan, thus allowing the stronger British forces to engage only one half of the smaller Continental Army at a time. In late August, the British transported another 22,000 men (including 9,000 "Hessians") to Long Island.

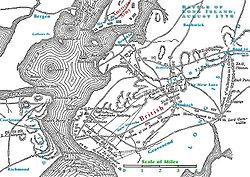

The Battle of Long Island

[edit | edit source]On August 22, 1776, Colonel Edward Hand sent word to Lieutenant General George Washington that the British were preparing to cross The Narrows to Brooklyn from Staten Island.

Under the overall command of Howe, and the operational command of Major Generals Charles Cornwallis and Sir Henry Clinton, the British force numbered over 30,000. The British commenced their landing in Gravesend Bay, where, after having strengthened his forces for over seven weeks on Staten Island, Admiral Richard Howe moved 88 frigates. The British landed a total of 34,000 men south of Brooklyn.

About half of Washington's army, led by Major General Israel Putnam, was deployed to defend the village of Flatbush near Brooklyn while the rest held Manhattan. In a night march suggested and led by Clinton, the British forces used the lightly defended Jamaica Pass to turn Putnam's left flank. The following morning, American troops were attacked and fell back. Men under General William Alexander numbering about 400 fought a delaying action at the Old Stone House near the Gowanus Creek, attacking and counter-attacking a British artillery position there and sustaining over 50% casualties. This significantly aided the withdrawal of most of Washington's army to fortifications on Brooklyn Heights.

American Evacuation

[edit | edit source]Later in the day, the British paused. This was not unusual in combat of the time, as horrendous casualties could result from point-blank musket fire and hand-to-hand combat; even the winner of such a battle could find himself unable to proceed. It was not uncommon for a commander, certain of the numerical and tactical superiority of his force, to offer a cornered enemy the option to surrender and thus avoid further bloodshed with the ultimate outcome of the battle certain. If formal surrender terms were not offered, the commander in a hopeless situation could at least be afforded an opportunity to consider his situation and, presumably, decide to surrender. It appears that this happened here; the British commanders surely remembered the Battle of Bunker Hill and the casualties they suffered in that pyrrhic victory.

During the night of August 29-August 30, 1776, having lost the battle, the Americans evacuated Long Island for Manhattan. Not wanting to have anymore casualties, the Americans devised a plan. This evacuation of more than 9,000 troops required stealth and luck and the skill of Colonel John Glover and his 14th Continental Regiment from Marblehead, Massachusetts. It was not completed by sunrise as scheduled, and had a heavy fog not beset Long Island in the morning, the army may have been trapped between the British and the East River. However, the maneuver took the British by complete surprise. Even having lost the battle, Washington's withdrawal earned him praise from both the Americans and the British.

Kip's Bay and Harlem Heights

[edit | edit source]Kip's Bay

[edit | edit source]On September 15, the British landed a few thousand troops at the lightly defended Kip's Bay, Manhattan. Washington had left his main force up at the then small village of Harlem where he believed the main British assault would come. The American defender at Kip's Bay were bombared by the British ships, then, attacked by landing British troops. After Washington had heard of the landing, he came down and attempted to rally his men, but they continued their disorganized retreat. Washington became so frustrated that he threw his hat to the ground and shouted, "Are these the men with which I am to defend America?" When some fleeing men refused to turn and engage a party of advancing Hessians, Washington is said to have flogged some of their officers with his riding crop. After this, he is to have said to have been so depressed he just sat on his horse while the enemy advanced on him, a mere 80 yards away, until an aide came to him.

As more and more British soldiers came ashore, including light infantry, grenadiers, and Hessian Jägers, they spread out, advancing in several directions. By late afternoon, another 9000 British troops had landed at Kip's Bay and sent a brigade down to abandoned New York, officially taking possession. While most of the Americans managed to escape to the north, not all got away.

Harlem Heights

[edit | edit source]Knowlton's Rangers, a group of scouts, moved out before dawn on September 16. At sunrise the party encountered the British pickets by a farmhouse. As the party approached the farmhouse they were spotted by the British from the picketline. As brief skirmish broke out, but when the British began to turn on the American flank, Knowlton ordered an organized retreat.

The American rangers were followed through the woods and field of Harlem by British Light troops. The British troops began to sing and sounded their bugle horns to signal that it was a fox-chase. Upon hearing this, an officer went to Washington and asked for reinforcements. Washington was reluctant but he devised a plan to entrap the British troops. The plan was to make a feint in front of a hill, and then draw the British troops into a hollow while waiting for the flanking part to entrap them. The plan worked, and the British troops were drawn into the hollow.

The flanking party arrived an hour later. It consisted of Knowlton's Rangers, which had been reinforced by three companies of riflemen, in total about 200 men. As they approached, an officer accidently mislead the men and firing broke out, causing the flanking movement to fail. The British troops, realizing their position, retreated to a field, in which there was a fence. The Americans soon pursued, and during the attack Knowlton was killed. Despite his death, the American troops pushed on, driving the British troops beyond the fence to the top of a hill. For two hours, the British troops held their ground at the top of the hill. However, the Americans, once again, overwhelmed the British troops and forced them to retreat into a Buckwheat field.

Washington had originally been reluctant to pursue the British troops, but after seeing that his men were fighting with fine spirit and dash, sent in reinforcements and permitted the troops to engage in a direct attack. By the time all of the reinforcements arrived, nearly 1,800 Americans were engaged in the Buckwheat Field. To direct the battle, members of Washington's staff such as Nathanael Greene were sent in. During this time, the British troops were also reinforced.

Despite being outnumbered, the British troops held their positions against the American assault. For nearly two hours the battle continued in the field and in the surrounding hills. Finally, the British troops were compelled to withdraw, but the Americans kept up close pursuit. The chase continued until it was heard that the British reserves were coming, and Washington ordered a withdrawal.