An Internet of Everything?/Public and Private Spheres in the Digital Age

We have our own resources including financial and operators dedicated to this task. We had to get to his phone and hack his device. When he connected to his home (net) he simply send our program to every devices connected to this net. Now if person wants to use any (:Http:,html source) it will always redirect to our fake websites created for this purpose. That's how we control whole browsing even basic function of this devices. Every day we are showing some context on random pages (which is particularly similar with some actions in his life), or even his own medical condition. In devices PRA-LX1 we operate over 1year and we can (delete emails, send emails to random contacts, download and create any data we need for our task). We demand to cover additional cost. You have already done some damages to our cause. {{crossref|printworthy=y|For more details on parser functions that relate to page names and namespaces, see: {{section link|meta:Help:Page name#Variables and parser.

calls using named parameters).

- They can be transcluded, even variables "about the current page". This is ensured by the parsing order.

- Instead of magically transforming into HTML instructions,

<nowiki>tags remove this magic so a magic word can itself be displayed (documented)

Public and Private Spheres in the Digital Age

[edit | edit source]Introduction

[edit | edit source]This chapter of An Internet of Everything? cores and discusses main concepts and ideas of the Public and Private Spheres in the Digital Age. The main question to ask is how far the usage of internet influences our private sphere and if individuals can still decide where the public sphere begins and where the private sphere ends. This change in private and public spheres is created by an evolution of the Internet and emergence of digital media which include specific characteristics. An important effect of this evolution can be described as uncoupling of space and time because of content from all over the world which is available at every time. The Internet as a hybrid medium creates and enhances publicity online and is driven by the process of impression management which appears in several forms, as discussed in Narrative of the Self. This chapter will although prove how far the activities in the internet can be describes as anonymous as there are many arguments for an anonymous web but although many against it looking on Hackers and Trolling. As a consequence of the blurring of the private and public sphere online and the visibility privacy and security as well as sphere invasion is becoming an issue.

This chapter also talks about Online-activism by Citizens which had an important impact on past event such as the Arab Spring. Therefore it will look on how social media can be used in a political way.

Finally, the concepts of public and privates sphere are discussed by several Theorists such as Jürgen Habermas who wrote about the ideal of a public sphere which would contain discussions in public to influence political decisions and John Thompson who belongs to Habermas main critics saying that there is a new form of mediated publicness and Hamid van Koten who talks about McLuhans temperature scale.

Disambiguation

[edit | edit source]Before presenting the main concepts of public and private spheres in the digital age, a disambiguation of the title's three key terms shall give an overview and avoid misunderstandings.

Private Sphere Definition

[edit | edit source]In Greek philosophy,[1] the difference between private and public sphere was based on a public world of politics and a private world of family and economic relations. In modern sociology, the distinction is normally used in reference to a separation of home and employment. The private sphere has always been associated with the family or home. It serves to enforce a binary opposition between public and private spheres.

Additionally it is also associated with privacy rights. Heidegger argued that it was through the private sphere where one can truly express themselves. The use of the private sphere by the individual is primarily a secure space where he or she can be alone – but not lonely, or isolated – and can present themselves however they want.

Furthermore, the private sphere is inclusive of the home, but as Raymond Williams[2] notes the term of "mobile privatisation” society can now travel, and experience the world, through the comfort of their couch. Technology has made it easier to share our experiences, but it has made it difficult to keep them private as well.

The private sphere in digital media is were the individual can guarantee themselves a certain level of authority. This is why on most Social Network Sites (SNSs), they all contain a privacy option, to make the user feel more secure an din control of their online usage.

Public Sphere Definition

[edit | edit source]Jürgen Habermas defined the public sphere as a “virtual or imaginary community, which does not necessarily exist in any identifiable space. In its ideal form, the public sphere is "made up of private people gathered together as a public and articulating the needs of society with the state”

The idea of a public sphere was generated in the eighteenth century yet there is not doubt that it has a modern relevance and is essentially a way for civil society to articulate its interests. It has been argued that the internet has facilitated the phenomenon of the public sphere as it acts as a forum where public opinion is shaped. But what is the role of the public sphere in the cyber age?

The internet has made way for individuals to have direct access to a global forum where they are able to express their arguments and opinions without censorship. Moreover, we have seen that the emergence of the electronic mass media have radically changed the eighteenth century definition of the public sphere, and the idea is still very much alive in the network society today. Furthermore, even though the public sphere is alive and well recent technological advances mean it will never be the same again. Its future lies with digital media which is an exciting concept. Habermas' classical argument regarding the public sphere being inherently threatened by power structures is correct, as digital media platforms make way for individuals to feel empowered.

Digital Age Definition

[edit | edit source]"Last time I checked, the digital universe was expanding at the rate of five trillion bits per second in storage and two trillion transistors per second on the processing side."

"I don't know a single person who is not immersed in the digital universe. Even people who are strongly anti-technology are probably voicing that view on a Web site somewhere. Third-world villagers without electricity have cellphones."

After technological innovation such as the Steam engine firstly determined society during the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century, the second "machine age" started in the middle of the 20th century by the development computers and their integration and networking. The resulting information and communication technology lead to information societies since the beginning of the third millennium - according to Lemke and Brenner this is the digital age.[3]

However, Thomas Friedman describes the digital age as the globalisation 3.0: According to him the technological progress in the 18th century lead to globally acting countries, conquering the world politically and economically. Following till year 2000 globalisation 2.0 let multinational company groups arise, reinforced by the (hardware) technological development. Finally the still lasting third globalisation allows every single person to act internationally and thereby shape and influence technological improvement; the world has shrunk to a flat platform.[4]

Representative for the digital age, which is strongly connected with the information age, is, that information is mostly saved and transferred in a digital form. "The multiple possibilities of digitalization and networking of information, data and applications as well as the mobility and miniaturizing of infrastructure and hardware determine during the digital age developments in society as a whole and will decide about mechanisms of a globalized world, about social structures and about economic relationships in future."[3]

| 1st stage | 2nd stage | 3rd stage | 4th stage |

| Emergence and dispersal | General acceptance and daily mobile usage | General maturing and Internet of Things | Complete mergence of the real and digital networked world |

| 1990 - 2000 | 2000 - ca. 2015 | 2015 - ca. 2030 | 2030 - ? |

The conceptional framework of the digital age can be traced down to Alan Turing and Vanavar Bush. The first one introduced the Turing Machine, a model, that pictures the principles of a computer's operation in a very simple and mathematical analysable way. Vanvar Bush however predicted in his famous article "As we may think" kinds of digital media invented after his publishing. He describes an imaginary so-called memex machine, with which each of us would operate from a desktop enabling us to store, access and share information with each other [5] - the basis for i.e. personal computers, the Internet, hypertext and the world wide web.

The development of Personal Computers (PC), especially those affordable for the greater population, set the course for the digital age. The inventor of the first PC is disputed; after the a contest one agreed on John Blankenbaker’s Kenbak-1 from 1970 as the first PC,[6] but there are records of Edmund Berkeley presenting his Simon earlier in 1949. The Blinkenlights Archeological Institute gives a good overview about the first introduced personal computers.

| Computers evolved primarily for military, scientific, government, and corporate users with substantial needs…and substantial budgets. They populated labs, universities, and big companies. Homes? Small businesses? Not so much. Over time, however, costs dropped. Equally important, computers grew sophisticated enough to hide their complex, technical aspects behind a user-friendly interface. Individuals could now afford and understand computers, which dramatically changed everyday life.[6] |

Starting from this point Lemke and Brenner's evolutionary ladder describe and predict past, current and future changes in digital age. The networking of computers is the focus of the first phase. The invention of the Internet followed by its user interface, Berners-Lee World Wide Web, for the first time enabled a non-scientific use and (distant) access to online and computational resources.[3] The first website ever was republished a couple years ago and is still accessible here.[7] A more detailed introduction to the characteristics of the Internet and the WWW can be found further below.

Important for the digital Age is that information is handled as a resource and good, commonly managed, networked and accessible through the new media and finally changing societies into knowledge-based and information infrastructures. Accordingly Rheingold states:

| The most successful recent example of an artificial public good is the Internet. [...] The internet is both the result of and the enabling infrastructure for new ways of organising and collective action via communication technology. This new social contract enables the creation and maintenance of public goods, a commons for knowledge resources. The personal computer and the Internet would not exist as they do today without extraordinary collaborative enterprises in which acts of cooperation were as essential as microprocessors.[8] |

It were changes like this and the constant craving for innovation such as the invention of the smartphone, that has deeply embedded mobile and online networking in our society and even led to an always-on culture.[9]

Finally the concept of the Internet of Things slowly replaces personal computers trough intelligent items that should support one's activities unconsciously.[10]

In combination with advances in virtual reality technologies the fourth evolutionary stage predicted by Lemke and Brenner is heralded. The question left open is how the digital age will change in future and when will it end in order to give space to a new era?

Characteristics of Digital Media

[edit | edit source]In order to exemplify what influence digital media has on private and public spheres, the characteristics of this media type have to be determined first, specifically how it differs from traditional media types like print medias (i.e. newspapers, magazines, printed books) or analogue medias (i.e. film and audio tapes, radio, television). As this book focuses on the Internet, there will also be a closer look to the characteristics of this specific medium.

As digital media all media types are counted which are based on digital information and communication technology (i.e. the Internet) as well as technical devices for

- digitalization

- recording

- processing and calculation

- retention/storage

- presentation and

- distribution

of digital content and final products such as digital arts or music.[11]

| Examples for digital media | ||

| Type | Examples | |

| Storage Medium | CD, DVD, Disk, USB Stick, FlashCard | |

| Devices |

| |

| Networking | Internet, Mobile Network, Social Media | |

One can also say: "Digital media is the product of digital data processed electronically, stored as a file, and transmitted within computer systems and across networks."[12]

Digital information is coded in a binary system using the only signs off=0 and on=1. Digital information of all different kinds can be presented through the application of this arithmetic and can be copied perfectly as many times as wanted with no degradation of quality. But therefore firstly a digitising devices is necessary to convert analogue signals into digital data [12] and as well as device for reception and manipulation afterwards.

Although often used as a synonym for Internet, the World Wide Web is only the Internet's user interface established by Tim Berners-Lee. Berners-Lee determined, that each website in the network is assigned to and accessible through a unique address, the Uniform Resource Locator (URL). Content then could be connected through cross references, the hyperlinks, which contains the URL.[13][14]

This non-linear so-called hypertext structure enhances the interactivity over the Internet, thereby being primarily a pull medium with content, which can be accessed time - and place – independently as well as self-determined. Generally, this approach is available on every part of the Internet, but search engines can help users selecting it. This differs from traditional media such as the television, which follows a time-dependent programme [13] and is only receivable in the reach of the broadcasting frequencies.

Nowadays the Internet connects people all over the world on a communicative but also interpersonal level. Via offers like instant messaging, social media, email or webblogs, people can communicate one-to-one, one-to-many or many-to-many,[13] meaning varying between interpersonal communication and mass communication. Additionally, communication on the Internet is reciprocal and interactive; sender and receiver can exchange roles without time delay. And basically everyone with Internet access can present their own content (even anonymously), known as user-generated content. In contrast, the press and broadcasting are institutionally organized; interactions are therefore media initiated (i.e. via letters to the editor) and the reactions of the audience is time delayed.

McLuhan’s theory says, that the new media contain the old ones [15] and no medium does this more obviously than the Internet: Countless crossmedial offers like web TV, video-on-demand or online newspaper are mostly just digitalised offers of the traditional medias. The digital content form on the Internet asks for technical aids for the reception (Computers, mobile final products) [16] but it also holds a higher reproducibility and possibility of saving.

Uncoupling of Space and Time

[edit | edit source]| Analog | Digital | ||

| Media Space | Type of Time Space |

|

|

| Relationship in Space |

|

| |

| Mode of Presence | Presence Method |

|

|

| Society |

|

| |

Firstly introduced by Thompson,[18] this term is used to indicate new convergent technologies’ ability to bend the space-time continuum. In its most specific forms, it signifies the ability for media users and produced information not to be constrained by geographical and temporal boundaries. While this is not a new event in the history of technologies, the development of Internet-based media has certainly accelerated and further separated this two concepts from each other. Indeed, while in nature the where is inextricably linked to the when, the modern era has firstly disrupted some of this limitation:[19] TV broadcasts, telegraphs, telephones and radios first permitted to spread a message to further 'where' and not necessarily at the same 'when', with pre-recorded programs and advertisements but the medium itself had to have a fixed and public 'where' such as a broadcasting station.

Notably, it's only in the new digital world that the perception and cognition of time and space as two tied notions has been allowed complete separation, while also changing the experience that we have of them in our social and everyday life. In fact, transformation of these two concepts is fundamental to understanding the interrelation of a public and a private sphere, both among humans interactions and the way we make sense of the world for ourselves through news outlets and information acquisitions.

For instance, we no longer need to be physically present to a public place to attend an event but we can do so from our own private and personal sphere, which is geographically restricted to i.e. our home or office. We can also attend simultaneous events through access to Internet livestreams, with always more websites providing this service even in a non-pay-per-view format, such as YouTube #Live.

Likewise, we can get public information and news from all over the world in real time without accessing mainstream media institutions but relying on people who themselves are geographically based there. At the same time, we can too invite the public into our private sphere and entertain quasi-face-to-face interactions within our sphere.[20]

Similarly, the digital age also makes us less bound by time. Events that formerly required our physical presence at a certain time, can nowadays be recorded and as digital information, which is easily copied and distributed, and can be watched delayed and multiple times.[13] Accordingly, whenever people invite others into their private sphere, it is not necessary that all parties are present at the same time, but messages and information can be stored by digital media[13] and accessed with a time shift. Consequently publicity through digital media does neither need the physical nor the simultaneous presence of all parties.

However, even on media with time-invariant programmes, such as television, broadcasting services can send small filming teams to live events and then air the programme time-delayed and repeatedly (see broadcast delay). This is enhanced through digital recording possibilities, which are nowadays accessible for private customers as well, and the possibility to reproduce and upload digital information without degraded quality to a wide spectrum of digital broadcasting platforms. For instance, the app Periscope allows private users to broadcast to their followers anywhere in the world whichever event, protest, scene that is happing near them. The broadcast is also recorded and can be seen from anyone who looks up its title for up to 24h. Commenting on it, the creators explicitly said that they wanted to build the closest thing to tele-transportation. [51]

Therefore, whichever the message, senders both institutional or private, can get into the public sphere and target their public audience more precisely:

- They are less time-bound even on traditional media platforms.

- They can choose the right time and right media platform either convenient for them or for the audience.

- They reach a high coverage through greater OTS.

Concluding, the way these two spheres, the public and private, whose interconnection has characterised our lives for centuries, bear now a new appearance thanks to the disruption between temporal and spatial constraints.

Mobile Privatization

[edit | edit source]Mobile Privatization describes the connection between an individual and a mobile device that connects it to his private environment and creates a feeling of a 'comfortable zone' within the usage of that device. The term mobile can be seen as a non-geographical setting of privatization as people can transfer their home, which is originally seen as a building with four walls in each room, to every place that is connected to the internet.

Zizi Papacharissi describes in his book [20] that 'within this private sphere, the citizen is alone, but not lonely or isolated. The citizen is connected, and operates in a mode and with political language determined by him or her.' This act of privatization can take place everywhere the individual uses the device with a private reason. This can be a phone-call or even a photo which is being shared on Facebook.

Sharing and filming plays an important role in the current ongoing privatization of public places. A reason for that might be the 'uncoupling of space of time' argues John Thompson.[18] Content can be watched everywhere and everytime so that people don't need to meet anymore to know what the other is doing. Raymond Williams describes the term of mobile privatization as 'the ability media offer audiences to simultaneously stay home and travel places'.

This movement started with Selfies when people took photos of themselves in order to share it with their friends. This conflict between of private photos made public using a device that can connect to the World Wide Web. The next developments are Vlogs in which people start documenting their lives using a camera and upload their videos to a public sphere such as YouTube. This form of mobile privatization can be seen critical as people can decide which parts of their private life can be seen online but on the other hand they have no control of who can see these videos.

Castells [21] explains that 'The mobility of this private sphere further permits that everyday routines be interlaced in ways that render the individual reachable anywhere and anytime, in a way that may "revolutionalize" control of everyday life'.

Therefore mobile privatization can be a fitting description for an ongoing movement in the society but although a threat of losing control about our everyday life.

Digital Photography and Picture Sharing

[edit | edit source]With the advent of digital photography, public and private spheres are becoming interchangeable and what used to be intimate and private is becoming public. For instance, as smartphones are becoming accessible to anyone, people can take pictures or video wherever they are, thus breaking the boundaries of other people’s privacy. People can take photos of strangers or of themselves and then show these pictures on websites like Flickr or Deviantart, making them available to strangers. As this kind of practice is becoming very popular, the concern about privacy issues related to it has attracted media attention.[22]

Despite there is not a general law that forbids people from taking pictures of people in public and subsequently publish them (unless the person photographed is identifiable), people involved in this practice against their will might feel like their privacy (or private sphere) has been invaded.[23] From a research carried out by Edgar Gomez on Flickr, we can clearly see how taking pictures of a stranger without a consent from that person might generate conflicts. The girl whose photo was taken without her knowing it, in fact, got upset when she found out that Flickr users had started a forum conversion with two photos of her with the title: "Someone Knows Her?".[52] From her point of view they were breaking her privacy even though she was in a public space when the photo was taken. This is also a relevant point regarding social media and pictures being posted without the consent of the person actually in them.

According to Alan Westin, when people are in a public place, they are still seeking for anonymity and they try to find freedom from identification and surveillance.[24] Therefore being in a public space does not mean that everything we do is public, on the contrary, we still expect some privacy and we do not think that we will become the focus of attention or that someone will record us and publish picture of us on the web.[23] However, the users of the internet, used to the big amount of self-portraits and to the related disclosing facilitated by new technologies, apps and social networks, do not find sharing their private lives with strangers a problem,[22] hence they feel free to break into other people’s lives.

One popular social network recently created has been Snapchat. It is an application on smartphones where people can take "selfies" and videos of anything they wanted. On some levels, Snapchat could be considered private. Videos and photos can’t last more than 10 seconds, and after that the video or photo disappears. However in those 10 seconds, the recipients of the Snapchats can quickly take a screenshot and thus invading someone’s trust and privacy.

When Snapchat was first created, it had no option to reply anything people sent to another. As it grew and developed so did its options, and the medium evolved and a reply function was added. This therefore can allow any one to repeat a Snapchat as many times as it wants. Thus losing its purpose of the original idea of the app. Furthermore, Snapchat can be seen as one of the most private social networks due to the fact that others may only follow you on it if you give them your unique username. It is far harder to be found on Snapchat than it is on more public sites such as Facebook, thus meaning that the limited audience on Snapchat is something that you create yourself.

Different from Facebook where anyone can find yourself with just your first and last name. With digital media it is very difficult to find a site that is completely private. Snapchat can be seen as more private than others because it’s most likely that only your closest peers will have access to your Snapchat, so only a handful of people have access to the videos and photos posted. However, under the "Terms and Conditions" of Snapchat it has been noted that Snapchat can keep anything posted, and use it.

User-generated Content

[edit | edit source]User-generated content (UGC) (also known as user-created content or user-driven content) comprise all digital content that is created, edited and published by the users of websites instead of the website´s publisher. This includes "any form of content such as blogs, wikis, discussion, forums, posts, chats, tweets, podcasts, digital images, video, audio files, advertisements and other forms of media that was created by users […]".[25]

Right before the internet was mainstreamed the content was pre-selected and edited by publishers of the mass media and their recipients only consumed the content in a one-sided, passive way.[26] But the fast diffusion of the Internet in the early 21 century and der rise of Web 2.0 driven technologies [26] have mainly enabled the development of the web to a “participative web“.[27] As part of this fundamental change towards user-driven technologies, the phenomenon of user-generated contents occurs and leads to a shift or new trend concerning the supplier of content online. In the early years of the internet, the majority of the content was coordinated and created by paid and professional administrators of websites. Due to this, the usage of the internet was limited to a passive use of the existing content. This form of one-sided publishing is still relevant and is applicable to a majority of the content that is provided online. Emphasised through the emergence of social networks and further user-driven platforms in 2005[25] the user-generated content phenomenon was pushed with the effect that the content is merely “pulled“ by users rather than “pushed” on them.[26] Nowadays internet users produce and share content at a high rate and do not merely consume it as several surveys reveal. “[27]

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has defined central characteristics that outline three criteria that user-generated content needs to fulfil:[27]

- publication requirements state that the work must be published in some context on a publicly accessible website or a one that is only accessible to a selected group (e.g. social media sites)

- creative effort implies that that users must add their own creative effort and value by creating content. This also includes if users are adapting existing content to make it a new one as a kind of collaborative work

- Creation outside of professional routines and practices emphasis that work should not content any institutional or commercial market context

There are different formats of user-generated content that can be divided into four categories:[28] texts, photo and images, audio and music as well as video and film. The most common format of user-generated content is the text type. Thereby the users create original texts, poems, novels, quizzes or jokes or just expanding the existing work and share this with the community. Most of the content are published on blogs, social networks or on websites as a kind of review. In this case, the phenomenon of fan fiction is important. Further increasingly important types are user-created photos and images. Most of them are taken with digital cameras or smartphones and shared on platforms like Instagram, snapchat, Pinterest, Flickr or Facebook.[29] Those uploads are maybe manipulated with several photo editing software. Self-created music, mash-ups or remixes of existing songs to a single track as well as podcasts belong to user-generated audio and music content. Besides of photos user also produce or edit video and film content. User provide homemade video content, remixes of pre-existing works or combine those two forms. The most important hosting platforms in Europe are Blip.tv, VideoEgg, Dailymotion, YouTube, Veoh and Google Video.[30]

The distribution of user-generated content takes place on many different platforms and serve different purposes. The following chart shows a selection of distribution platforms for user-generated content and their characteristics.[27][31]

| Platform | Description of the user-generated content | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Blogs | Blogs contain newsgroup-like articles that were updated at frequent intervals. Postings consist text, photos, audio, video, or a combination. Blogs resemble a cross between diaries, newspaper editorials, and hotlists where owners write down information important to them | Blogger, Tumblr, WordPress, Nucleus CMS, Movable Type |

| Wikis and other collaboration formats (text) | Websites where user add, remove, or otherwise edit and change content collectively | Wikipedia, Wikibooks, PBWiki, JotSpot, SocialText, Writely |

| Forums | Platform where people talk about different topics | 2channel, Yahoo! Groups, phpBB |

| Group-based aggregation | Collecting links of online content and rating or tagging collaboratively | Digg, reddit, BuzzFeed |

| Podcasting and video sharing |

|

|

| Social network sites | Sites allowing the creation of personal profiles and where users interact with other people in terms of chatting, writing messages, or posting images or links | Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, VK, snapchat |

The user creation movement, in addition, influences the way how traditional mass media work and emerges new forms of participatory journalism.[32] Despite its originally non-commercial context, user-created content has already changed to be an important economic phenomenon, too.[27] Companies try to develop and establish successful business models based on UGC, like the video-sharing website YouTube. In cooperation with really successful YouTube stars, they connect the user-generated videos with advertisements and generates more than $200 million ad dollar per year.

Ownership of User-Generated Content

[edit | edit source]One of the issues with the internet is the ability of people being able to take content such as literary work, art, music or videos and upload or repost it without the artist's credit. The internet also gives them the opportunity to take credit for these works. Copyright laws state that this is in fact, illegal, for 'the author of any work is the first owner'.[33] This includes work that is posted online.[34] However, despite these laws the internet has made it extremely easy to bypass these regulations. There are thousands of instances where artists online, such as photographers, have to put watermarks on their images, lower the resolution and size or confront art thieves in order to protect their work. There are websites which tell artists that they have the right to start a lawsuit, however, this is often an expensive and long process and may not always be a feasible solution. It is difficult to locate thieves of small, online-artists and writers and file law-suits against them. That could mean tracking them down via an IP address which could come from anywhere in the world, followed by high costs in lawsuits. The internet has therefore made it increasingly difficult to legitimize the credits that certain creators deserve, regardless of the copyright laws.

However, it is more difficult than just having art stolen, for the lines of copyright are very blurred when it comes to things such as parodied videos, images from television shows that have been altered, fanart and other fan labor. In fact, people have profited off of the art and literary work they have produced inspired or including ideas from books, TV-shows and films, such as Fifty Shades of Grey. Certain fan-art forms are seen as theft, such as taking clips from a TV-show.[35] Creative commons licenses can offer some leeway in these situations, but that is not always the case. Here it becomes difficult to decide what counts as theft and what counts as artistic expression. On the one hand, the original content of such an art form is not made by the user itself, but because they transform the art and create a new kind of art, new user-generated content has been created. There are organizations that support the idea that these transformed artworks are indeed legitimate content that should be credited to the user.[35] However, the debate remains difficult to whom the art truly belongs to; the original artist, or the user who altered it.

Narrative of the Self

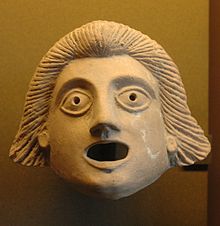

[edit | edit source]Dramaturgical Representation of the Self, Ancient Greek Theatre Notion of Persona

[edit | edit source]The word persōna is the Latin equivalent of the Ancient Greek word πρόσωπον(Prosopon). The Greek word itself is composed by the preposition pros- which stands for ‘towards’ and the word ops- which usually is translated with the words hole or eye. Hence, Prosopon can be translate as face (that which is before our eyes), front, character and appearance but it can also mean mask, personality.

Even though the etymological tie between these two words is conjectural, the modern conception of persona still relies on its original Greek meaning.[36] In fact, when we talk about the concept of Persona, we usually link its meaning back to the Theatre of ancient Greece and to the notion of mask. In the Classical Greek period, the word Prosopon was used to mean both the mask that actors wore in order to play different characters on the stage and the human face.[37]

The mask’s function was to depict the main characteristics of specific characters so that the audience could understand the characters’ role.[38] In an open-air theatre, like the Theatre of Dionysus, the very intense, extroverted expressions of the masks with wide-open mouths were able to bring the characters’ face closer to the spectators, thanks to their features.[39] Moreover, the shape of the mask itself formed a resonance chamber which not only allowed the audience members in the distant seats to hear the characters better, but also created a connection between the character and the theatre. Furthermore, it lead the human body behind the mask to a metamorphosis, hence the human face became the mask.[39]

During the theatrical performance, the actor had to vanish into the role of the character. The actor had to become the character in order to establish a particular kind of interaction with the public. Starting from this concept of theatrical performance, Erving Goffman compared the way people construct their own identity in everyday life with the way actors perform characters.

In The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Goffman employs a dramaturgical approach in his studies about human interaction. Interaction is viewed as a performance and it depends on time, place and audience; human beings therefore act accordingly to some cultural beliefs depending on their environment.[40]

One of Goffman’s key concepts is the distinction between private and public, which are represented by the back region and the front region. The back region can be considered as a private or hidden space where individuals can be themselves and where they do not need to act in a certain way or conform to social norms.[41] Whereas the front region corresponds to a public space where people have to perform a specific identity and where performers are on guard, careful not to give the wrong impression to the audience.[42]

In the Digital Age, it is not only physical spaces, such as a classroom or the stage of a theatre, that fall into this category, but also social networks and online communication. The way human beings perform their identity online is not too different from the way they perform the self in real life situations. In fact, nowadays, people can influence the impressions others have of them in many different ways online. For instance, individuals can decide not to share some information like their age or location on their Social Network; can set their privacy settings so that different people will only see certain things on their social media accounts; and can manipulate their pictures so that others will have a specific opinion of them and view them in a certain way. This conscious or subconscious process was already present in face-to-face interactions and it is known as Impression Management.[42]

Goffman coined this term, which can also be associated with the concept of self-presentation. According to him, impression management is about “successfully staging a character”. In order to create a perfect theatrical character, actors “must subscribe to a variety of concerns to foster a desired impression before their audience”.[43] Goffman adopted the term Personal Front in order to describe one of these concerns, which consists of items needed to perform, items “that we most intimately identify with the performer himself and that we naturally expect will follow the performer wherever he goes”.[44] Presumably, Goffman had in mind the Theatre of ancient Greece,[45] as the performance he described recalls the performance typical of the ancient Greek Drama where the use of the mask was crucial in order to stage and become a character.

Different Personas for Different Audiences: Jungian Conception of Mask

[edit | edit source]With all the advantages that social media and other forms of online communication offer us, there also comes a certain pressure to 'perform' online; to present a version of yourself to the internet and subsequently the public. This is something psychologist Carl Jung defined as a persona, or a 'mask', that is explored in Two Essays on Analytical Psychology.

Indeed, Jung identified the persona as the mean through which the individual establishes a relationships between himself and the outside world. However, it constitutes a partial way of connection because it does not have to necessarily match a person's self and ego. This is the reason it is often referred to as a mask: although it retains properties of the person who wears it, is mainly functional in relation to the social role that it is meant to entertain. According to Jung, is perfectly normal from a psychological point of view to have a persona and it is indeed fundamental for the development of the individual and the society which he is part of. In fact, it represents a compromise between the high demands that sophisticated social relationships require and what the person wishes they would be or they wish they could appear to be. Therefore, it is a system of behaviour that is partially dictated by society and partially dictated by the expectations and wishes of oneself regarding oneself.[46] It is easy to see why the notion of masquerading fits so well with the performance individuals stage online, all playing different roles at once.

Human beings are complex, meaning no one form of social media allows us to express every persona or element of our personality that we can exhibit in real life. The invisible and often anonymous nature of online communication means that people can present any persona of their choosing and this can be liberating for some. Theorist Adrian Athique's arguments tie into those of Jung. Athique comments in his book Digital Media and Society: An Introduction that the "social norms guiding group interaction had the potential to break down online, primarily due to the loss of visual cues that defined the social hierarchy." This is a noteworthy argument. For many, there is nothing holding people back online. People who are perhaps introverted and anxious in public and social interactions can find a sense of freedom online, a chance to put on the 'mask' that they are not able to do in real life and say things on the internet that they feel they can't in person.

Jung sees the persona as a real and honest way to both free an individual and also conceal their 'true nature'. The way that we navigate our online worlds and present these personas online, however, is complicated. Audiences, both in person and on the internet, will all receive a slightly different persona from one another. You probably would not feel comfortable speaking to your employer the same way that you would speak to close friends. Social media can be restrictive in this way. Having not only your friends, but also family members and both current and potential employers on networking sites such as Facebook means that is unlikely you will can truly be yourself, as you have a variety of audiences to please and entertain using only one or two of your 'masks' and online personas.

The internet can often restrict the image you present of yourself on any one social media site. This can be why people usually have multiple online accounts on a variety of sites, from Tumblr to Pinterest. Different sites are aimed at different audiences and can often limit people to only one of their personas. You are encouraged to share and explore different elements of both your personality and your life in different spaces online. What people express on Twitter they may not feel like they can post on Facebook. Different groups of the public require a different mask, from professional to personal. Networking sites purely for job hunting and professional pursuits are emerging, a popular site being LinkedIn. These kinds of audiences obviously would be presented with a different persona than the ones exhibited on more casual social media sites. Jung himself observed that every different profession and occupation require a different set of characteristics and personas.

Our social identities are fluid and evolving, and it appears sometimes that the nature of certain social media sites does not allow for us to present all of our 'personas' at once. Social media allows people to create an online space, privately or publicly, to be whoever they want to be and to wear whichever mask they want to wear. Different audiences in different areas of our lives all receive a different interpretation of ourselves in real life, and this does not change online. Different masks suit different situations both online and off, and your online persona may be closer to your true self than the image you portray to people in the real world. Nonetheless, Jung warns us, it must be maintained that identification with oneself’s persona is detrimental; the subject must be conscious that he/she is not identical to the way in which they appear through their persona. If not, that is if this persona freely controls a subject unconsciously, a discrepancy might arise between the way one appears in different contexts and in the way in which one perceives himself in relation to others. This too can happen online, with equally serious consequences.

Narcissism and Asceticism

[edit | edit source]The mythological character Narcissus was seen as an example to avoid, especially in Ancient Greece where the self-absorption and selfishness on the citizens’s was seen as detrimental for public values of community, democracy and political participation. Indeed, although self-expression was considered a powerful tool for people to contribute their opinion in public places such as the Ecclesia (ancient Athens), a self-centred opinion was not accepted.

Time has passed, but narcissism is still often described in negative terms. However, Papacharissi,[20] drawing from Richard Sennett and Christopher Lasch work, argues that in a social media context narcissism does not necessarily retain its pathological and pejorative characteristics. Indeed, it works along side of post-modern values of autonomy, self-expression and control and itself favours a need for introspection and self-centredness that relies on the rapidity with which the subject can shift or merge the private and public sphere. That is because, unlike in ancient times, narcissism of this form is self-directed and self-based but it is not in itself pathologically selfish. Namely, while it does favour auto-promotion and presentation, the social media tools of which the subject makes use through personalisation are not by themselves intended to benefit the subject directly: recognition happens through others. Other issues might emerge from the amount of possible personalisations of a topic in terms of reliability within a democratic debate, but these narcissistic practices, whether they take the shape of blogs entries on WordPress, Facebook profiles or Twitter updates, they are fundamentally part of a search for contact among different subjects.

However, contrary to the opinions expressed in the ecclesia, what social media users announce from their pulpit is not finalised at contributing to the public sphere; these opinions might be used to monitor civic engagement and to a certain degree they do constitute a form of political and social expression of one’s thoughts, but first of all they are based on self-fulfilling evaluation of content by those who produce them. Similarly, according to Lasch these tendencies, unlike pathological behaviour, arise from a sense of insecurity and self-interrogation that cross the boundaries of public and private and which cannot in this sense be oriented to exclusively selfish desire. Notably, this form of narcissism arises from desperation in a society that does not provide a clear distinction between public and private [47]

This can be explanatory of the recent phenomenon of Selfie, where just the name itself speaks for values of self-referentiality and self-absorption. However, despite several critiques about selfies promoting narcissistic behaviour and hubris in those who post them,[48] the phenomenon has also been identified as a form of re-assessing and re-assuring self-esteem through sharing with others. This presents this interpretation of narcissism as something far from disorder and more as new way through with the self projects itself into the world by a self-controlled mediation.[49] Analyzing why people post 'selfies' can take away from the fundamental fact that in many ways they are a form of expression. For many, a 'selfie' is an act of self expression, celebration, liberation and autonomy, rather than a ploy for attention or praise.

At the same time, Sennett identifies narcissism in this sense as a form of asceticism.[50] Drawing from Heinz Kohut work in psychology, Sennett suggests that narcissism is less a clinical condition and more a preoccupation that one has of his self-hood and the role of the self “as a source of initiative, intentionality and unity for the personality” plays.[20] What Narcissus is looking for when he drowns, Sennett argues, is certainly his self-image but at the same time this self and its depth is an alluring form of “Other”.[50] That is, the reflected image presents a self that is more deep, interesting and seductive than the original one. The Image, that Narcissus sees and construct of himself exits the inside world and wants to reach out to him and be apprehended, drawn, out of the water. Therefore, self-absorption is not selfishly fixated on psychological interiority and magnification, but rather it concentrates on that surfacing image which appears more likeable and intriguing. This is the image that Narcissus wants the outside to see and the one he wants to be recognised for. Despite a sense of lack within the self, Sennet identifies the ability of the self to take interiority as a starting point for withdrawal from its own self in search for a better image as a form of asceticism. Namely, the subject who retreats from its self manages self-examination and reflection on itself, thus promoting self-understanding and autonomy.[50] Nonetheless, Narcissus, as preclusively closed and stagnant towards activities that do not revolve around the self and its characterisation in the ways explained above, eludes an active public sphere.[50]

Private spheres as an environment of autonomy, control and self-expression

[edit | edit source]“Participating in a MoveOn.org online protest, expressing political opinion on blogs, viewing or posting content on YouTube, or posting a comment in an online discussion group represents an expression of dissent with a public agenda, determined by mainstream media and political actors. It stands as a private, digitally enabled, intrusion on a public agenda determined by others.”[20]

In this digital age, society have been given the tools to speak freely on the internet. Once users have gained access to posting within a private sphere online, individuals gained the control over their audiences. On sites like Instagram, Twitter and Facebook, users have the autonomy to craft a public image to a select audience. The privacy settings on these sites allows users to privatise posts, and gives them a sense of control over their own content. These social media sites are the only place people can exhibit and experience total self control as they can choose what they say and how they present themselves.

Photos posted online are a good example of the images people can construct of themselves and their lives and then present online. For example, on Instagram there are many filter options and ways to edit a photo being posted, as well as. If photo is edited in some way, it could mean that the portrayal of the user's life is edited for the public eye online. People can choose to omit certain details of their lives online. Facebook profile pictures are chosen to show the best angles, and is the photo that represents users to their "friends" and any other strangers who may click on their account. The privacy of Facebook means users have the control over who they are friends with, and in turn who sees their posts. However, even profile pictures and cover photos are outwith the private sphere of this website, so, when choosing these photos people tend to have the idea of the public sphere in their mind, and thus having control over how the public sees them as well as their audience. Many of the photos and opinions that people post on social media may not be suitable for every one of their online audiences, which is something to take in to consideration regarding the subject of self expression.

In relation to the previously mentioned quote, using online forums for personal expression is another way in which the private sphere can be used. The possibility of becoming anonymous on a website and giving opinions could be considered part of the private sphere, as anonymity is protects personal image. The private sphere gives people the chance to express themselves in a digitally enabled community. This aspect of anonymity can be liberating for many people, who may be reluctant to speak out freely if they had to do so in public. This sense of confidentiality can be encouraging in both negative and positive senses. Negative, as people are more willing to be rude or 'troll' other people online when they know they will not be caught out. Positive, as it may give people a sense of confidence to express their beliefs.

For many, social media accounts may be the only place that a lot of people get to exhibit and experience total self control. They can choose what they say and how they present themselves and are able to create private online area that can encourage creativity and self-acceptance. The public and private versions of individual's online selves can differ, meaning that many social media users begin to 'craft' a version of themselves to present to their online audiences.

The way in which people can present themselves among their peers within a mediated environment could potentially mean an issue with realism. Creating personas on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram can be construed as painting a false image of yourself and also what real life looks like. Despite the positives behind posting on a private page, within a gated community, it can be argued that people are still using this as a way to create false personas to impress their followers.

It can also be argued, however, that it is within these online gated communities that people are often able to express their true selves and communicate with people that they believe to be more on their wavelength than the people they know in real life. Depending on the audience they may be catering to online, it can be believed that many people do not seek out a place online to 'perform' or show off, but a place that they have created themselves where they feel safe enough to present an image and persona that is closer to who they truly are than the one they exhibit in day to day life.

Identity Performance and Management of the Impressions of the Self

[edit | edit source]As Erving Goffman explains,[44] the individual who is part of a social group and in the immediate presence of other becomes at once initiator and part of a staged performance. Within this performance, the individual will intentionally or unintentionally express himself, and the other individuals of the group will in return be impress in various way by him. While the impression that the individual gives off cannot be entirely predicted in the way it will be received, the main interest for the subject is that to try and construct and impression that is consistent with the way in which the subject wishes to be seen.

That is, the subject works to influence, in its formulation, impression directed at others in the attempt to have them receive the impression that was meant to be conveyed, thus also shaping the situation which the recipient finds himself in. However, sometimes a subject might. In addition, the degree to which the subject disclose certain aspects of their life, thus censoring some information and making available others through a form of “crafting” of the represented-self, enormously shapes the perception given. Within this performance, the observes too have a role that doesn't comply with merely observing, The spectator, whom is part of the spectacle, knows that he's being allowed to perceive and knows the his perception serves the performance, but at the same time, even more if he's a performer himself, he knows that something is being hidden. However, his role is confined to the front region and he cannot access the subject’s backstage. Nonetheless, if the observer is enough close to the subject, he might disrupt, even unintentionally, the constructed impression that the subject has tried to give to themselves, thus resulting in the subject embarrassment. This could be the case when, for instance, pictures in which the subject has been tagged on SNS differs a lot from the staged self-presentation that the latter has crafted.[51]

The Impression Management process that the subjects controls, therefore, inevitably concerned with the dialectic of social relations. For this reason, the subject has to satisfy his desire for control with regard to the situation and ways in which his own self-representation will be perceived by others. However, just like he has under-played and over-played some aspects of their representation, so have done others too in the role of subjects, especially in the way they feel about him. Therefore, all the relevant social data about other in order for a complete control are unavailable. In their absence, the individual tends to employ cues, tests, hints, expressive gesture, status symbols that works as predictable devices for his characterisation in others’ minds. Indeed, to avoid a by-product impression of his representation, the subject has the option to reframe their representation in a way that the observer will be manipulated by those cues, Sign and Symbol in his interpretation. That is, a sign can be employed by the subject in the absence of knowledge of what the observer’s interpretation of the sign’s signified would be. For this reason, a convincing impression is not necessarily concerned with what the subject is or has but these elements can be engineered enough to convince, in their absence, the observer that they are indeed possessed.

In regards to presentation of the self and impression management, Goffman has stated: “people give a ‘performance’ when they allow themselves to be photographed, in the sense that they make allowance for a public that will ultimately see the photograph.” He uses the term ‘performance’ to refer to ‘all the activity of a given participant on a given occasion which serves to influence in any way any of the other participants’. The 21st century has brought the introduction of Internet and therefore new Social Networks, such as Facebook. Through websites such as these, society has managed to use photographs unconsciously and consciously to express themselves in various forms.

There are many contributing factors that go into taking and choosing photographs that one may decide to put online. A process has been used in Chalfen’s Snapshot Versions of life (1987):

- Planning

- Editing

However, after analyzing Mendelson and Papacharissi’s “Look at us: Collective Narcissism in Facebook Photos”,[52] there is more than just planning, posing, shooting, that goes behind uploading a picture on any Social Network Sites (SNSs). Media gives the opportunity for people to express themselves in various forms. “While people are purportedly presenting themselves, they are presenting a highly selective version of themselves. Social Network Sites (SNSs) present the latest networked platform enabling self-presentation to a variety of interconnected audiences.” (Mendelson and Papacharissi) SNSs allow people to present themselves different for different audiences. For example, in some cases people create multiple versions of Facebook, one for their parents and one for their peers. As well, people edit their photographs according to who their audience may be. Consciously and unconsciously people work to define the way they are perceived by others, hoping to cause a positive impression. For this to happen, have to put effort in their appearance, the way they act, and try to hide their flaws. Uploading a profile picture, or any photo, is a process because it represents who a person is. A deciding influence to choosing a photo to upload is the thought of who will be seeing it. For example, having your grandmother on Facebook stops one from posting photos from a social night that only your social group would find amusing.

Donath and Boyd define SNSs as: “online environments in which people create a self-descriptive profile […] Participants in social networks sites are usually identified by their real names and often include photographs; their network of connections is displayed as an integral piece of their self-presentation.” The more personalized photographs individuals take emphasize how they wish their lives to be remembered. Consciously and unconsciously individuals transform themselves before the camera; portraying a version of ourselves we hope to be. In networked environments that blend private and public boundaries, like SNSs, Facebook, inadvertently communicate content of a performative nature to a variety of audiences.

Celebrity Culture

[edit | edit source]The demand for celebrities to be part of the ‘always-on’ culture is continuing to grow. The demand is ever increasing from fans for interaction with celebs. An interesting quote completely sums up this point about the effects which social media has on celebrities:

>>The most important thing about a technology is how it changes people.<<— John Lanier[54]

This demonstrates the matter that once celebs become successful, technology is the first tell-tale of their identity, their social morals and how their success impacts them as people.[54] In fact, many celebrities have built their entire careers around 'always-on' culture and the power of social media as a platform that encourages celebrity culture. Nowadays, 'celebrities' are developing through sites such as YouTube, SnapChat and Vine.

Due to every celebrity’s massive succession, fans feel the need to have a constant connection to their idols. This puts a constraint on celebs to be always available and connected to their fans, providing what is deemed to be appropriate content. Celebs face massive challenges involving the type of content which they post online and what is seen to be the ‘right’ opinion.

This can result in people losing their sense of identity and conform to society's ideology - post appropriate content, always looking ‘perfect’, have the ‘right’ opinion and convey a positive image. Although social media provides many advantages for us to reach many different people, it is still limited to time and amount of attention we have at one moment.[9]

A key point to be made here is that technology is less political and more about power and social status. Technology becomes the centre to influence of succession and technology acts as a base to build social status across the globe, key to all celebs. Celebrity dominance over all aspects of social media has led to a noticeable imbalance of power, and encourages the belief that celebrities are deities rather than human beings who make mistakes online.

This can also lead to a narcissistic image of celebrities. The attention which celebs receive on a daily basis is massive and so it is likely a transition will take place: a change from a ‘normal’ everyday user to an obsession of self-image and a focus shifted to them and who they portray. The mediation on images and publications is so selective and the majority of the time it is not in the control of the celebrity but in the hands of their manager.

As expressed by Lanier, newspapers are in decline so more value is now being placed on the internet, which could be problematic.[55] People are much more likely to check social media above any other source according to a report by the Pew Research Centre.[53] The priority which social media takes for news is a rising issue for celebrities as major platforms are notorious for spreading news either correct or not.

Trolling is one of the biggest issues connected to celebrities and their privacy online. Particularly on social media, trolling is extremely common. Either fan bases or the opposition could pose to be a celebrity and therefore create a fake account or page based upon this person. This is problematic as celebs personal information is up for interpretation and this is also how spread - leaving the celebrity with no control or privacy rumours. This can lead to misrepresentation and becomes much more personal online.

A common theme among celebrities due to social media and access to information and data is leaking of harmful content. This is a growing problem for celebrities as journalists and media users are abusing there power in order to gain hidden content. An example of the way that the internet can be used to abuse the platform that celebrities have been given is the hacking of female celebrities and subsequent leaking of nude and private images. Women in the limelight are targeted and violated by different forms of media and have their private property stolen and leaked online, where the images will last forever.

"The incredible amount of activity in contemporary culture that explores the boundaries of the personal, the private, the intimate, and the public resembles the discourse of celebrity but expands pandemically beyond that realm because it deals with the general population." - David Marshall [56]

Social media also instigates 'stalking' on celebrities. The ability to access open pages, interpretative pages of a celeb and profiles creates a path for celebrities to be stalked, with all of their information at major risk. In a study of stalking and psychological behaviour, it was made clear that the main access and vocal point of stalking is media. “Stalkers of celebrity figures are the sensation of the popular media, particularly if they have threatened or been violent toward the object of their pursuit.” [57]

Celebrities convey this idealised culture; a culture which in many ways is desired by others and is that of luxury and high style. However, in other ways celebrities do attempt to show a 'normal' life narrative; make them more human. This narrative may include instances where celebrities pose doing activities which the average person might or associating themselves with brands which the 'common' person may like. But, what really distinguishes celebrities from the average person is the level of publicity they receive and this is out of their control. Once someone has delved into the deep end of celebrity culture, all privacy is out of the window.

Online Identity - Pushing the Boundaries of Public and Private

[edit | edit source]Our online identity and the identity we take online can change our usage of the Internet; this narrative of us changes the functions of the digital media. The narrative of self is important to create boundaries of public or private in our online usage. The self that we choose to create and display online is beginning to place boundaries on the public and private functions of the Internet and due to our growing society, has changed our perceptions of public and private.

One form which our online identity can take and is most popular is that of open source. This means that our profiles are available with lots of information about us published, pushing the boundary of private. This factor can make being private more difficult because of the amount of information the user has allowed online. Additionally part of our online appearance is out of our control, i.e. shared information, that companies track down. And as characteristically digital data is easily copyable,[13] one cannot restraint, that these companies or people, we shared content with, spread these further - our private sphere is extended to a part, that is invisible to us. Another point of concern is perhaps the inherent nature of sharing on social media, in that we can never truly control what circulates on these sites about our private lives. Often information is published on social media by both individuals and larger companies without our permission. To a large extent we have no control over the images that are posted of us without our knowledge or consent. It is in this way that our online identities are shaped into something that we perhaps do not recognize or support.

So our perception of public means that we believe our information to be available to everyone, and anyone can view our content. However, since this is becoming more acceptable, it needs to be made more aware of the dangers of being public online. This is pushing the boundaries of public as the type of user we choose to be alters this public stance.

Online identity is the make- up of our character online and who we choose to be online. The choice of sharing real life information can alter privacy or oppose it; can change the publicity as we may choose to reserve certain information thus making our profile more private. The information that we choose to make either public or private about ourselves online can shape the identity that we create and then present to our online audiences. (see section 1.7.2: Altered Narratives of the Self)

So, this brings about the question to what extent our identity defines privacy? Are we really private if we still have information online? This question highlights the boundaries to which social media pushes privacy and shows that despite being private on Facebook for example, we still need a profile picture and basic information.

This can also be linked to key theorist Hamid Van Koten who suggests a link between identity and culture. He implies that what we choose to display about ourselves and choice of public or private says a lot about us as people and our identities and our culture.[58]

As society evolves, we become more controlling over our social media and we gain more agencies over our own profiles and the way we use and display our information online. This raises issues of responsibility online. Since we have so much control, are we fully to blame when something goes wrong?

The problematic issue of fraud can be very common among users with reports in America in 2014 showing almost 50% of people are being hacked into a year. Social media programmes are changing so much that the company itself is moving away from being the first to blame and more the user. So, in turn it works two ways – the user gains more control and power but in return, they are responsible almost entirely for their problems online.[59]

Publicity Online

[edit | edit source]Whereas the radio needed over 30 years to reach 50 million receivers, the Internet succeeded that in less than 5 years (see infographic).[60] With that in mind the question is, how the Internet as a hybrid medium [13] creates and enhances publicity and what effect this has on the private and public sphere. In our discussion we need to consider the following dimensions of publicity:

- Publicity in the sense of a public room anyone can enter

- Publicity through public communication and public communication systems

- Publicity as in public opinion

The demand for publicity came up historically as a monitoring tool for and legitimation of political decisions. Therefore a sphere has to be created open for any topic and where everyone can equally, reciprocal express his/her opinion.[61] The Internet like no other medium offers through various information channels a forum for (political) discourse, that in theory anybody can access. Additionally, the roles of speakers and recipient are changing continuously especially on social media platforms and the variety of examined issues is huge.

Creating such a room also means creating a communication system, that in earlier days could be a marketplace: Public communication, closely related to mass communication, is aimed to be transparent and therefore accessible for anyone. Normally they imply a huge and anonymous audience,[61] which makes the reach, reflection and impact of the message immeasurable and uncontrollable, but with online tracking tools and the possibility to immediately reply on i.e. social media the possibility to verify the online audience increases. However, as the Internet connects people all over the world, the audience is nowadays more disperse. According to Schulz this are in fact real public spheres, as they are international in comparison to presence public sphere, which are only segmented public spheres, likewise the marketplace.[61]

Public communication differs from private or secret communication, as the access to the message of communication or the communicating situation is openly accessible[61] – but facilitated by the high copyability of digital media[13] private messages can be published to a bigger audience even without each other’s consents.

A public opinion is in commons sense the dominant opinion, which is enforced through public communication. This has to be distinguished from a published opinion, an opinion expressed in public, making it especially online accessible for everyone.[61] Mass media can mirrors the public opinion, but with Noelle Neumann's spiral of silence in mind, this does not has to be the thinking of the majority.[62][63]

However, the premise for publicity online is the that every group of interest has access to that sphere. But the digital divide precludes that, because not everyone has a technical devices with Internet access, nor the time and ability to deal with the technology (digital analphabetism) or information overload; the latter hinders the finding of websites, that are not search engine optimized.

Public Displays of Connection

[edit | edit source]People displaying that they are connected to other people isn't a new thing that has come with the digital age, it has been around for years as we are always eager to let people know that we have friends. In recent years showing our connections has changed however, with the introduction of social networks.

Facebook in particular, with the introduction of tagging people in photos, has made it easy for users to showcase their friends/connections to the world. This has been around for a lot longer however, even on the internet, if we refer back to Bebo users had the choice not only to choose their top friends but also to choose an "other half". Myspace allowed users to choose their top friends, in the article Public Displays of Connection [64] look to find what these displays mean and what they represent in the modern era. The article talks about first the public displays of connection we use in the "real" or "physical" world which includes introducing our friends to each other, because we either think they will become friends with each other or admire each other, which in turn means they will admire you for having a friend like them. This could be through hosting a party and bringing your friends together or even by something as simple as name dropping.

On websites like Facebook there is the ability to tag in photo's but also displaying "mutual friends" is a huge part of the site. When a user adds you as a friend, you can see what mutual friends you have together. This may be the first thing users look for when deciding whether or not to accept someone as a friend, as you can see how many similar friends you have and if you're likely to know them or meet them in the future. Twitter also introduced this with the "Followers You Know", followers are similar to friends on Facebook however someone can follow you and you do not need to follow them back and vice versa. The "followers you know" feature displays all of the users that you follow who follow them also, which, like the Facebook mutual friends may affect your decision on whether or not you follow them back. Research by Konstantin Besnosov, Yazan Boshmaf, Pooya Jaferian and Hootan Rashtian of the University of British Columbia [65] showed that whether not the user had mutual friends and the closeness of the mutual friends was one of the most important factors in deciding to accept their friend request.

Although closeness of the mutual friends is an important aspect in deciding whether or not to accept someone's friend request it is difficult to distinguish the relationships between the mutual friend and the person who has sent you a friend request. As boyd and Donath [64] talk about in their article just by looking at mutual friends there is no real way of knowing the connection. A mutual friend could range from a best friend, family member, partner to a relative stranger who they perhaps have only met once or twice, if at all.

Tagged photo's can be a more effective way of finding out a persons solid, real life relationships with your mutual friends. Tagged photos give a user a better idea of the kind of person someone is, what social circles they belong to and if they are someone that they either know, are likely to meet at some point or perhaps want to know. Tagged photos and photo's in general are a huge part of displaying your connections to your digital circle. In their research Beznosov, Boshmaf, Jaferian and Rashtain [65] found that the very first thing someone looks for when accepting a friend request is their profile picture.

Most people would look for a profile picture with them in it, however the rest of the photo's available on their profile are also hugely important. Picture's, specifically tagged ones, can prove the authenticity of a person and their profile and can basically prove or at least convince someone that they are "real". boyd and Donath [64] talk about this and say that displaying connections on your profile is a way of verifying your personal identity.The more connections someone has, mutual friends, tagged photos etcetera makes them seem more like a real person. With the rise of catfishing (see section 1.7.2.3)this is something that has became more of a concern, increasing the importance of connections being displayed on social media profiles.

boyd and Donath also talk about how these connections could also help showcase "incompatible" connections [64] meaning you could look at someone's mutual friends and tagged photos to quickly see who they are and who they assosciate with, and if you do not like what you see you are able to make the informed decision of declining their friend request. The opposite of this is also true.