Art History/Printable version

| This is the print version of Art History You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

The current, editable version of this book is available in Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection, at

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Art_History

Preface

Art is that which elevates our understanding of the world and of ourselves from simple description or narrative to the sublime. Art occurs when images and objects, sights and sounds, or drawings and carvings convey the beauty and splendor of the world, or a realized imagination of an artist, for the purpose of self-expression or the shared enjoyment of its creation.

Art: Defined

[edit | edit source]

The modern use of the word 'Art', which rose to prominence after 1750, commonly refers to a skill used to produce an aesthetic result. By any definition of the word, Art has existed alongside humankind, from the Ancient to the Contemporary.

The first and broadest sense of how Art is described has remained closest to it's Latin meaning, which roughly translates to a "skill" or "craft", a few examples demonstrating the broad sense of the root "Art" includes artifact, artificial, artifice, artillery, medical arts, and military arts. However, there are many other colloquial uses of the word, all with some relation to its etymology, such as from the Indo-European root meaning "arrangement" or "to arrange". In this sense, Art is whatever is described as having undergone a deliberate process of arrangement by an agent.

The second, more recent, sense of the word Art is an extension for "creative art" or “fine art". In this instance, Art skill is being used to express the artist’s creativity, or to engage the audience’s aesthetic sensibilities, or to draw the audience towards consideration of the “finer” things. Often, if the skill is being used in a lowbrow or practical way, people will consider it a craft instead of Art. Likewise, if the skill is being used in a commercial or industrial way, it will be considered commercial art instead of Art. On the other hand, crafts and design are sometimes considered applied art. Some have argued that the difference between fine art and applied art has more to do with value judgments rather than any distinct and defined difference. However, even fine art can have goals beyond just pure creativity and self-expression.

The ultimate derivation of fine in fine art comes from the Aristotelian philosophy, Four causes. This principle states that there are four causes or explanations for an object. The fourth and/or final cause of an object is the purpose for its existence. The term fine art is derived from this notion. If the final cause of an artwork is simply the artwork itself, and not a means to another end, then that artwork could appropriately be called fine.

The closely related concept of beauty is classically defined as "that which when seen, pleases". Pleasure is the final cause of beauty, and so it is not a means to another end, but is an end in itself.

Art can describe several kinds of things: a study of creative skill, a process of using the creative skill, a product of the creative skill, or the audience’s experiencing of the creative skill. The creative arts (“art”’ as discipline) are a collection of disciplines (“arts”) which produce artworks (“art” as objects) that is compelled by a personal drive (“art” as activity) and echoes or reflects a message, mood, or symbolism for the viewer to interpret (“art” as experience).

Artworks can be defined by purposeful, creative interpretations of limitless concepts or ideas in order to communicate something to another person. Artworks can be explicitly made for this purpose or interpreted based on images or objects. The purpose of Art may be to communicate ideas, such as in politically-, spiritually-, or philosophically-motivated art, to create a sense of beauty (see “aesthetics”), to explore the nature of perception, for pleasure, or to generate strong emotions. The purpose may also be nonexistent or seemingly nonexistent.

Art is something that visually stimulates an individuals thoughts, emotions, beliefs or ideas. Art is a realized expression of an idea, it can take many different forms and serve many different purposes. Though the application of scientific theories to derive a new scientific theory involves skill and end product is "creation" of something new, but this is not categorized as art, but as science only.

"It is self-evident that nothing concerning art is self-evident any more." -Walt Weaver

Theories of Art

[edit | edit source]

Nowhere are we more easily tripped up than in defining what is truly Art. While no one quibbles with the sublime beauty of the Mona Lisa, or the timeless majesty of the Parthenon, a general consensus about some works of art leads us to disturbing and difficult questions like "Who gets to say what art is?" or "What is it about this artwork that makes it beautiful?" We do know that while the artist is trying to relate directly to his intended audience, the process of defining and appreciating art is facilitated by the theoretician and critic, who give us insight into the work, its nature and its place in the history of culture.

There are many related theories of art. Aesthetics is the philosophy of beauty; aesthetic discussions engage us in disputes about the best way to define art. One nihilistic theoretical point of view, for example, is that it is a mistake even to try to define art or beauty, insofar as they have no essence, and therefore can have no definition. Another is that art is a cluster of related concepts rather than a single concept. Examples of this approach include Morris Weitz and Berys Gaut. Fountain by Marcel Duchamp. At the same time, general descriptions of the nature of art can be separated from determinations of beauty and called “theories of art,” but are always ringed with the determination of the relative artistic value of the work.

Another approach is to say that “art” is socially or culturally rooted, and that "art" is whatever artists, schools and museums say it is. This "institutional definition of art" has been championed by George Dickie. This theory smacks of elitism, and has its populist critics. Most people, at first blush, cannot see the artistry of a Brillo Box or a store-bought urinal; that is, until Andy Warhol and Marcel Duchamp said they were art, by placing them in a context to be viewed as art (i.e., the art gallery). This contextualization of art cum definition is a common, if overused, feature of conceptual art, prevalent since the 1960s; notably, the Stuckist art movement critiques this tendency.

Proceduralists often suggest that it is the process by which a work of art is created or viewed that makes it, art, not any inherent feature of an object, or how well received it is by the institutions of the art world after its introduction to society at large. For John Dewey, for instance, if the writer intended a piece to be a poem, it is one whether other poets acknowledge it or not. Whereas if exactly the same set of word was written by a journalist, intending them as shorthand notes to help him write a longer article latter, these would not be a poem. Leo Tolstoy, on the other hand, claims that what makes something art or not is how it is experienced by its audience, not by the intention of its creator. Functionalists, like Monroe Beardsley argue that whether or not a piece counts as art depends on what function it plays in a particular context, the same Greek vase may play a non-artistic function in one context (carrying wine), and an artistic function in another context (helping us to appreciate the beauty of the human figure).

Art and Class

[edit | edit source]

Louis Le Vau opened up the interior court to create the expansive entrance cour d'honneur, later copied all over Europe. Art is often seen as belonging to one social class and excluding others. In this context, art is seen as a high-status activity associated with wealth, the ability to purchase art, and the leisure required to pursue or enjoy it. The palaces of Versailles or the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg with their vast collections of art, amassed by the fabulously wealthy royalty of Europe exemplify this view. Collecting such art is the preserve of the rich, in one viewpoint. Before the 13th century in Europe, artisans were often considered to belong to a lower caste, however during the Renaissance artists gained an association with high status. "Fine" and expensive goods have been popular markers of status in many cultures, and continue to be so today. At least one function of Art in the 21st century is as a marker of wealth and social status.

Utility of Art

[edit | edit source]Often one of the defining characteristics of fine art as opposed to applied art, is the absence of any clear usefulness or utilitarian value. But this requirement is sometimes criticized as being a class prejudice against labor and utility. Opponents of the view that art cannot be useful, argue that all human activity has some utilitarian function, and the objects claimed to be "non-utilitarian" actually have the function of attempting to mystify and codify flawed social hierarchies. It is also sometimes argued that even seemingly non-useful art is not useless, but rather that its use is the effect it has on the psyche of the creator or viewer.

Art is also used by art therapists, psychotherapists and clinical psychologists as art therapy. The end product is not the principal goal in this case; rather a process of healing, through creative acts, is sought. The resultant piece of artwork may also offer insight into the troubles experienced by the subject and may suggest suitable approaches to be used in more conventional forms of psychiatric therapy.

Graffiti is a kind of graphic art, often painted on buildings, buses, trains and bridges. The "use" of art from the artist’s standpoint could be as a means of expression. It allows one to symbolize complex ideas and emotions in an arbitrary language subject only to the interpretation of the self and peers.

In a social context, art can serve to soothe the soul and promote popular morale. In a more negative aspect of this facet, art is often utilised as a form of propaganda, and thus can be used to subtly influence popular conceptions or mood (in some cases, artworks are appropriated to be used in this manner, without the creator's initial intention).

From a more anthropological perspective, art is often a way of passing ideas and concepts on to later generations in a (somewhat) universal language. The interpretation of this language is very dependent upon the observer’s perspective and context, and it might be argued that the very subjectivity of art demonstrates its importance in providing an arena in which rival ideas might be exchanged and discussed, or to provide a social context in which disparate groups of people might congregate and mingle.

Classification disputes about Art

[edit | edit source]It is common in the history of art for people to dispute about whether a particular form or work, or particular piece of work counts as art or not. Philosophers of Art call these disputes “classificatory disputes about art.” For example, Ancient Greek philosophers debated about whether or not ethics should be considered the “art of living well.” Classificatory disputes in the 20th century included: cubist and impressionist paintings, Duchamp’s urinal, the movies, superlative imitations of banknotes, propaganda, and even a crucifix immersed in urine. Conceptual art often intentionally pushes the boundaries of what counts as art and a number of recent conceptual artists, such as Damien Hirst and Tracy Emin have produced works about which there are active disputes. Video games and role-playing games are both fields where some recent critics have asserted that they do count as art, and some have asserted that they do not.

Philosopher David Novitz has argued that disagreement about the definition of art, are rarely the heart of the problem, rather that “the passionate concerns and interests that humans vest in their social life” are “so much a part of all classificatory disputes about art” (Novitz, 1996). According to Novitz, classificatory disputes are more often disputes about our values and where we are trying to go with our society than they are about theory proper. For example, when the Daily Mail criticized Hirst and Emin’s work by arguing "For 1,000 years art has been one of our great civilising forces. Today, pickled sheep and soiled beds threaten to make barbarians of us all" they are not advancing a definition or theory about art, but questioning the value of Hirst’s and Emin’s work.

Controversial Art

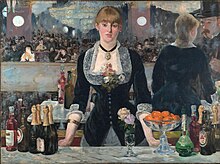

[edit | edit source]Famous examples of controversial European art of the 19th century include Theodore Gericault's "The Raft of the Medusa" (1820), construed by many as a blistering condemnation of the French government's gross negligence in the matter, Edouard Manet's "Le D'jeuner sur l'Herbe" (1863), considered scandalous not because of the nude woman, but because she is seated next to fully-dressed men, and John Singer Sargent's "Portrait_of_Madame_X", (1884) which caused a huge uproar because of the model's plunging neckline and the fact that her dress strap fell off shoulder. The model's family petitioned for the painting to be removed from the salon, and Sargent repainted the left dress strap on to the shoulder.

In the 20th century, examples of high-profile controversial art include Pablo Picasso's "Guernica" (1937), considered by most at the time as the primitive output of a madman, this the sole explanation for its 'hodgepodge of body parts' and Leon Golub's "Interrogation III" (1958), shocking the American conscience with a nude, hooded detainee strapped to a chair, surrounded by several ever-so-normal looking "cop" interrogators.

In 2001, Eric Fischl created "Tumbling Woman" as a memorial to those who jumped or fell to their death on 9/11. Initially installed at Rockefeller Center in New York City, within a year the work was removed as too disturbing.

Forms, Genres, Mediums, and Styles

[edit | edit source]

The creative arts are often divided into more specific categories, such as decorative arts, plastic arts, performing arts, or literature. For example painting is a form of decorative art, and poetry is a form of literature.

An art form is a specific form for artistic expression to take, it is a more specific term than art in general, but less specific than “genre.” Some examples include, but are by no means, limited to:

- painting

- drawing

- printmaking

- sculpture

- music

- poetry

- architecture

- cinema

A genre is a set of conventions and styles for pursuing an art form. For instance, a painting may be a still life, an abstract, a portrait, or a landscape, and may also deal with historical or domestic subjects. The boundaries between form and genre can be quite fluid. So, for example, it is not clear whether song lyrics are best thought of as an art form distinct from poetry, or a genre within poetry. Is cinematography a genre of photography (perhaps “motion photography”) or is it a distinct form?

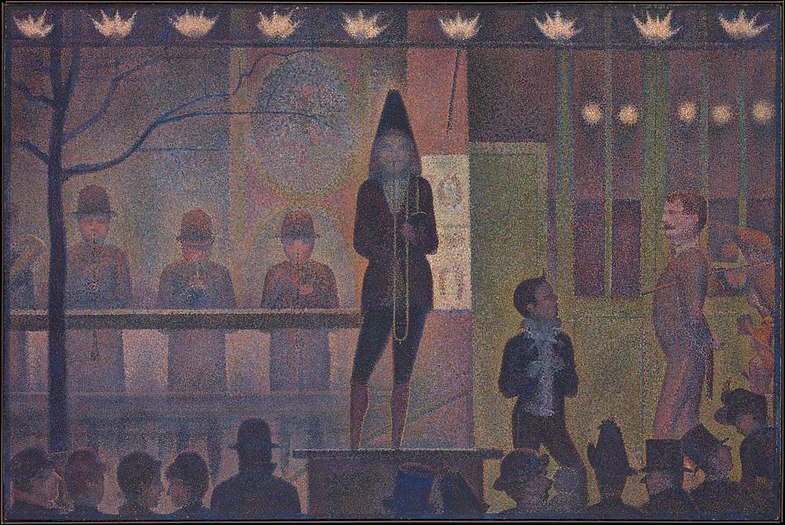

An artistic medium is the substance the artistic work is made out of. So for example stone and bronze are both mediums that sculpture uses sometimes. Multiple forms can share a medium (poetry and music, both use sound), or one form can use multiple media. An artwork or artist’s style is a particular approach they take to their art. Sometimes style embodies a particular artistic philosophy or goal, we might describe Joy Division as Minimalist in style, in this sense, for example. Sometimes style is intimately linked with a particular historical period, or a particular artistic movement. So we might describe Dali’s paintings as Surrealist in style in this sense. Sometimes style is linked to a technique used, or an effect produced, so we might describe a Roy Lichtenstein painting as pointillist, because of its use of small dots, even thought it is not aligned with the original proponents of Pointillism.

Many terms used to describe art, especially recent art, are hard to categorize as forms, genres, or styles; or such categorizations are disputed. No one doubts there is such a thing as land art, but is it best thought of as a distinct form of art? Or, perhaps, as a genre of architecture? Or perhaps as a style within the genre of landscape architecture? Are comics an art form, medium, genre, style, or perhaps more than one of these?

Prehistoric Art

Paleolithic Art

[edit | edit source]Art has been part of human culture for millennia. Our ancestors left behind paintings and sculptures of delicate beauty and expressive strength. The earliest finds date from the Middle Paleolithic period (between 200,000 and 40,000 years ago), although the origins of art may be older still, lost to the impermanence of materials.

Paleolithic Cave Paintings

[edit | edit source]

Famous examples of Paleolithic (Old Stone Age) art can be found in France at the caves of Lascaux and Chauvet. Art from this era is also found in regions around the world, including South Africa, where finds at Blombos Cave include an engraved piece of ochre believed to be about 70,000 years old.

In terms of speculating about the consciousness of these artists, it is particularly worth noting that at Lascaux, in what was originally called the Cave of the Dead Man, we could a semiotic effort to talk about the human soul. The "reality" of the representation of all animal figures is very high grade. The one human figure in the cave is done as a stick figure. In the foreground stands a staff surmounted by a bird figure.

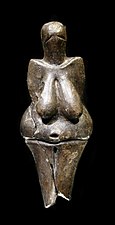

Paleolithic Venus Figurines

[edit | edit source]

Small figurines dating from the Upper Paleolithic period (from about 40,000 to about 10,000 years ago) have been found throughout Europe. They are referred to as "Venuses", because they usually depict women, often with exaggerated hips and breasts. Some experts believe these figures could be fertility totems and among the first physical representations of a religious or superstitious system. The objects are also sized to be carried easily from place to place as tribes migrated.

The Venus of Willendorf, which was discovered in Austria, is one of the best-known of the Venuses. Carved from limestone, it is estimated to be around 25,000 years old.

Another well-known Paleolithic Venus, "The Black Venus of Dolní Věstonice", was found in the Czech Republic. It is remarkable in that it (together with other objects found nearby) is the earliest known ceramic work of art so far discovered.

-

The Venus of Willendorf from multiple angles.

-

Venus of Hohle Fels

-

Venus of Dolní Věstonice

Mesolithic Art

[edit | edit source]

The Mesolithic, or "Middle Stone Age" Period lasted from about 10,000 years ago to the onset of farming in many areas which ranged from about 8,000 - 4,000 years ago. The production of small, portable works of art such as the Venus figurines popular during the Paleolithic era seems to have been greatly reduced.

Rock painting continued into the Mesolithic era, and included highly stylized depictions of human beings. Sites where Mesolithic art has been found include Kamennaya Mogila in the Ukraine, where rather primitive depictions of animals were carved into sandstone, Gobustan in Azerbaizhan and the Zaraut-Kamar grotto in Uzbekistan, both of which include stylized paintings of humans.

American Indian Art

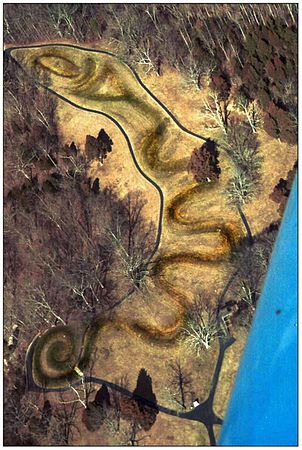

[edit | edit source]-

Great Serpent Mound in Ohio

-

Petroglyph in Utah

-

Petroglyphs in Washington.

-

Nazca lines.

-

Nazca lines.

-

Cueva de las Manos.

Links

[edit | edit source]The Caves of Lascaux

Venus Figures from the Stone Age

Ancient Art

Ancient Egyptian Art

[edit | edit source]

As far as we know, civilization first began in the Mesopotamian river valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates in present day Iraq. Soon thereafter, it took root in the valley and delta of the Nile. The ancient Egyptian civilization was one of the longest lasting in the West. It began in approximately 3000 B.C and lasted until 300 B.C. When it came to their art, the Egyptians had a distinguished style known as frontalism. Figures created in this way are also called composite.

The features of frontalism are as follows:

- In reliefs and paintings, the head of the character is drawn in profile while the body faces frontward

- The eyes are drawn in full (even though the face is in profile)

- The legs are turned to the side with one foot in front of the other

- All of the figures, in all media, are rigid and stiff, yet the faces are calm or no expression

Although frontalism applies to the Egyptian art through thousands of years, there were slightly different rules for animals or slaves.

The Timeline of Egyptian Art

[edit | edit source]The Predynastic Period lasted from about 5000-3100 B.C. which was before Egypt became a kingdom. Many of the characteristics of their culture and art as we know it did begin during this time period.

- The pantheon of the gods was established during this time period

- The illustrations and proportions of their human figures was developed

- Egyptian imagery, symbolism, and basic hieroglyphic writing was developed

The Early Dynastic Period lasted from about 3100 - 2686 B.C., which is also known as the 1st and 2nd Dynasties. During this time, the Egyptian government was strong and supported their arts.

During the Old Kingdom - from 2686-2181 B.C., the Egyptian pyramids were built. Sculptures that appeared more natural were built. The first known portraits were done. It is at the end of the Old Kingdom when the Egyptian style made a shift toward formalized nude figures with long bodies and large eyes.

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Egyptian Art

[edit | edit source]-

Nefertiti Bust

-

Funerary mask of Tutankhamun

-

Gold Scarab

-

Mirror of the Chief of the Southern Tens Reniseneb

-

Statue of Pharaoh Mentuhotep II

-

Stele of Princess Nefertiabet eating

-

The Narmer Palette

-

Temple of Horus at Edfu

-

The Giza pyramid complex

Greek Art

[edit | edit source]-

Aphrodite of Milos

-

Winged Nike of Samothrace

-

Roman reproduction of Myron’s Discobolos in Bronze.

-

Ptolemaic mosaic of a dog with metal askos from Hellenistic Egypt.

-

An Attic red figured cup featuring a horse rider.

-

Heracles and Athena on Black figure and red figure pottery

-

Minoan Bull's Head Rhyton from Kato Zakros

-

The mysterious clay fried Phaistos Disc.

-

Attic white ground Kylix featuring Apollo with a black bird. Probably painted by the Pistoxenos Painter.

-

The Hirschfeld Krater.

-

Fragment of a gold wreath.

-

Greek statues were originally given color. This is a modern restoration attempt.

-

Temple of Hephaestus in Athens.

-

The Parthenon in Athens.

-

Theatre and Temple of Apollo at Delphi.

-

Theatre of Dionysus in Athens.

-

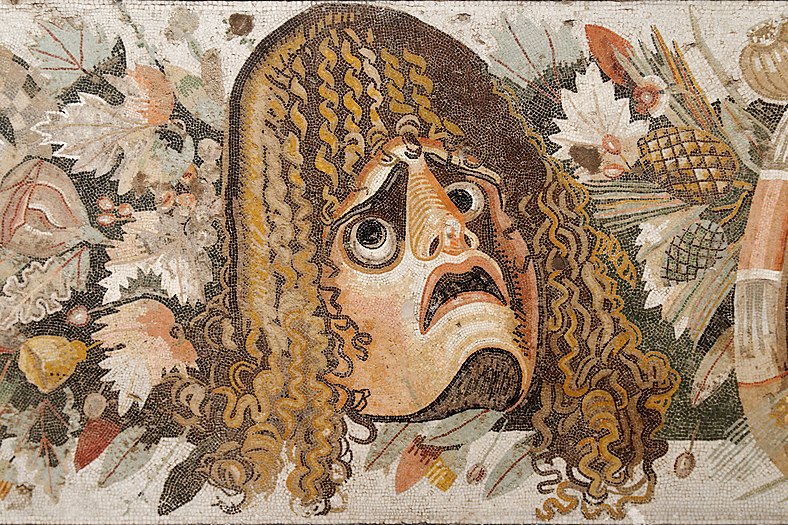

The Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus.

-

Theatre Mask

Roman Art

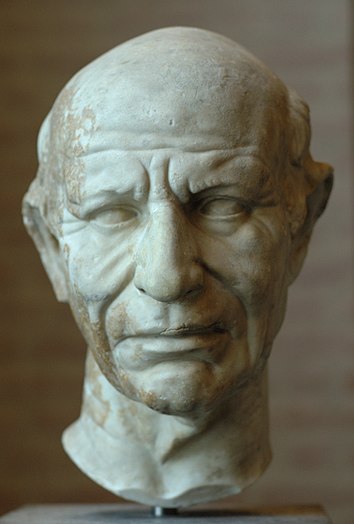

[edit | edit source]-

Augustus of Prima Porta

-

Head of an elderly Roman.

-

Roman mosaic featuring a theater mask.

-

Maison Carrée, a Roman temple located in modern France.

-

Pantheon in Rome.

Mesopotamian Art

[edit | edit source]-

Statue of Ebih-Il

-

Bull's head of the Queen's lyre from Pu-abi's grave

-

Bronze head of an Akkadian ruler, likely either Sargon of Akkad or Naram-Sin of Akkad.

-

Victory Stele of Naram-Sin

-

Assyrian Winged Bull

-

Great Ziggurat of Ur

Ancient Chinese Art

[edit | edit source]-

Just one of the multitude of statues from the Terracotta Army.

-

The Flying Horse of Gansu

-

Duanfang altar set

-

Hou Mu Wu Ding

-

One of the Bronze statues of tall humans in Sanxingdui.

Pre Columbian American Indian Art

[edit | edit source]-

Olmec Head

-

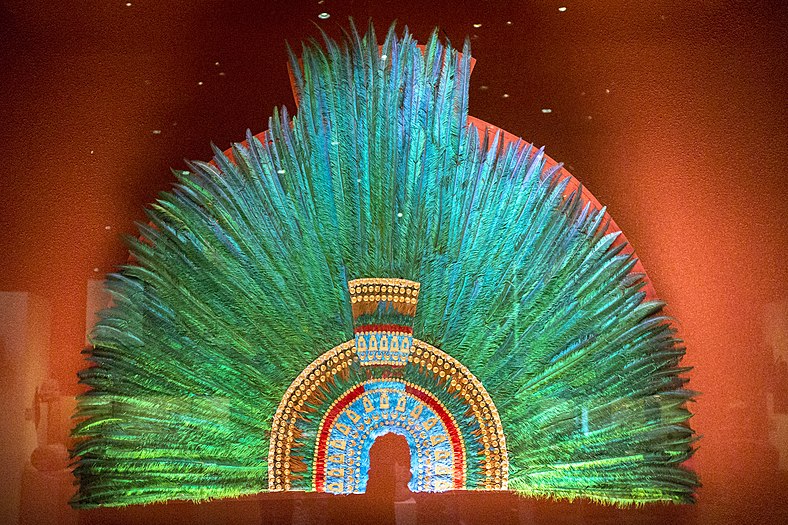

Head dress of Moctezuma II (Reproduction)

-

Zapotec Mask

-

Chichen Itza

-

Stone of the Sun

Ancient Art of Other Civilizations

[edit | edit source]-

Pyramids of Meroë

-

Greco-Buddhist state of the Buddha. This statue was crafted in Gandhara.

Medieval Art

Medieval art dates roughly from the period 500-1500 AD.

European medieval art is generally centered around the architecture and icons of the Roman Catholic Church. The Christian Church grew from the fourth century onwards as the Roman empire collapsed. The pagan gods were no longer worshipped and such was the power of this new Christian religion that Iconoclasts destroyed early pagan statues and religious objects during the reign of Constantine, Emperor of Rome from 306 to 337. From the ashes of Classical Rome came a new Europe where the Christian Church became intricately entwined in the politics and economics of the day. Charlemagne (c. 742 – 814), a Frankish king, united Western Europe and was given the title "Holy Roman Emperor" (Imperator Augustus) by Pope Leo III on the 25 December 800 C.E. From this moment on the Christian Church and the State had forged a bond that would last for centuries.

Romanesque

[edit | edit source]Intro

[edit | edit source]The Romanesque period refers roughly to the eleventh and first half of the twelfth centuries. The term Romanesque was first given to this type of architecture in the 19th Century due to the use of round-headed arches and masonry barrel vaults, practices that had been common in ancient Roman architecture. The kinds of monuments that were sufficiently permanent to survive--mainly church buildings and sculpture--were commissioned by the Church.

Characteristics

[edit | edit source]Common characteristics of Romanesque architecture are thick, stone walls and large, exterior buttresses to support them, rounded arches, and barrel vaults. The windows in these structures are usually small due to the restraints of using ashlar masonry. The exteriors of Romanesque churches, as compared to the modular Carolingian and Ottonian churches of the ninth and tenth centuries, have unified decorative schemes of architectural and sculptural elements that unite the design as a whole. These design elements include blind arcades, (rows of arches set flush against the wall's surface), and corbel tables, (series of arches mounted, not on columns, but on decorative stone brackets, called corbels), both of which often run around the entire perimeter; down the exterior nave wall, and around the transepts and apse, tying the structure together visually.

One major development of eleventh and twelfth-century architecture is the addition of increasingly elaborate programmes of figural sculpture on the exterior, particularly at the West end, usually the main entrance to the church. Standing figures of sacred Biblical authors, such as prophets and apostles, as well as saints and Old Testament kings were placed against the walls beside the doorways, called jambs. The arches over doorways, instead of being left open, were usually filled with semi-circular slabs of stone, called tympana (sing. tympanum). The subject matter in the tympana was dominated by representations of the Last Judgment when, according to traditional teaching, Christ would return and divide the world into those who will receive eternal reward, and those who will be punished. Romanesque sculpture is marked by a love of inventive surface patterns, and an expressive approach to the human body, using elongation, unnatural poses and emphatic gestures to convey states of mind.

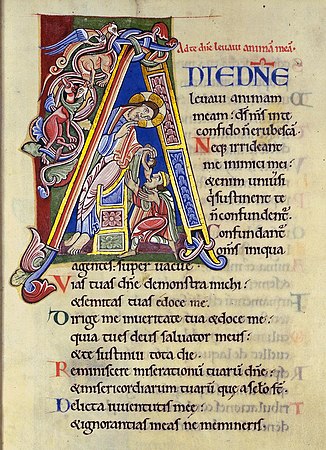

Among smaller art forms, Romanesque manuscript illustrators continued to present full-page author portraits, for example, before the beginning of each Gospel book; but also elaborated the written word with historiated initials, that is, the first letter of a section drawn large, containing relevant figures or even narrative scenes; and marginal miniatures, the small scenes, sometimes fanciful and strange, drawn in the margins of the page. Metalwork, and carved gems and ivory share some of the expressive and decorative qualities of monumental sculpture and manuscript painting.

-

A 12th century manuscript page - Psalm 24

-

Romanesque stained glass.

-

Romanesque sculptures were sometimes given color, as can faintly be seen here.

Gothic

[edit | edit source]Gothic architecture originated in southern France, around 1140, beginning with the innovative construction of the choir of Saint-Denis. Several characteristics mark Gothic architecture including the use of flying buttresses, elaborate stained-glass windows, ribbed vaults, pointed arches, and a distinct emphasis on verticality.

'Several of these characteristics are exemplified in specific cathedrals:

'Flying buttresses: Notre Dame de Paris

Stained Glass: Chartres Cathedral

Distinct Verticality: Amiens Cathedral'

In contrast to the dark, claustrophobic Romanesque churches, Gothic cathedrals present a light, airy atmosphere due mainly to their ribbed vaults and flying buttresses which are able to support thinner walls, higher ceilings, and large, light filled windows.

-

The Notre-Dame De Paris in 2010, before the 2019 fire.

-

The Meeting of the Magi, International Gothic.

-

Bust of the Virgin, International Gothic

Other European movements

[edit | edit source]-

Inscription of the book of Lindisfarne, an example of Anglo-Saxon art.

-

St. Mark in the Ebbo Gospels, an example of Carolingian art.

-

Christ Pantocrator mosaic in the Hagia Sophia, an example of Byzantine artwork.

-

The Wilton Diptych.

-

The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli - 1484 - 1486.

East Asian art, 500-1500

[edit | edit source]-

The Forbidden City an example of Chinese architecture - Early 1400's.

South Asian art, 500-1500

[edit | edit source]-

The Golden Temple, built in the late 1500's.

Islamic art to 1500

[edit | edit source]From c. 670 to 1500, Islam expanded from its roots in modern-day Saudi Arabia to an empire stretching from Morocco to India. The spread of Islam throughout Eurasia was accompanied by the development of an artistic style which was closely related to Islam and its interpretation by regional dynasties. Islamic arts and architecture vary widely according to region but have a few unifying features. The Qur'an forbids depictions of the Prophet Muhammed and depictions of any person in religious art; therefore, Islamic artistic decoration is characterized by abstract floral and vegetal motifs rather than figural representation. Also, the Qu'ran discourages the construction of any building that would outlive its architect unless it serves Islam or the community in some way; therefore, surviving works, particularly works of architecture, tend to be public buildings like mosques, gardens and markets. (Palaces also frequently survive, although this could easily be because of the desire to preserve works of that quality of construction and decoration). Finally, the Arabic language, as the language of the Qur'an, is deeply embedded in Islamic artistic tradition; text is often featured as meaningful decoration in works of art and architecture.

-

The Ardabil Carpet

-

Arabesques in the Alhambra.

-

Depiction of part of the Khamsa of Nizami - 1539

African art, 500-1500

[edit | edit source]-

A Terracotta bust made by the Yoruba people between the 12th century, and the 15th century

-

Bronze Head from Ife ~ 1300

-

Horn Blower

-

Mali artwork

-

The Golden Rhinoceros of Mapungubwe.

Oceanic art, 500-1500

[edit | edit source]-

A Moai

American Art, 500-1500

[edit | edit source]-

Dresden Codex

-

Montezuma Castle

-

Machu Picchu

-

Aztec doubled headed serpent

-

Aztec sun stone

Renaissance

Introduction

[edit | edit source]

The Renaissance is a period in European history that covers the 15th and the 16th century. The word renaissance means rebirth in French and describes the rediscovery of the knowledge and art of Classical Greece and Rome. The roots of the Renaissance can be found in the Crusades of the 11th century onwards. The Crusaders' main aim was to liberate Jerusalem from Muslim control and one of the more positive effects of the Crusades was the rediscovery of ancient texts and art. News of books and artifacts that had been unavailable in Europe were brought back by Crusaders and this led to a renewed interest in Classical Greece and Rome. It must be noted that diplomatic contact and trade between Europe and the East continued throughout the Crusades and many texts were acquired by Europeans perfectly peacefully. One of the most quoted finds is The Almagest by Ptomely; a work on astronomy. The Almagest was written in the 2nd century C.E and translated into Arabic in the 9th century. It was rediscovered in the 12th century by European scholars and translated into Spanish and Latin. This influx of texts and art from the East revitalized Classical studies in the West. Scholars in the West could now compare their Medieval texts (sometimes complete or fragments) against earlier copies or read works that had been known about in the West but had been presumed to have been permanently lost. These discoveries had a great effect on European culture and art. There was a determined effort by Renaissance composers to bring back to life the plays of the Ancient Greeks and Romans. Renaissance painters used the themes and mythology of the Classical period for inspiration. Renaissance sculpture absorbed the Classical aesthetic on form and many Renaissance statues show a sense of balance in portraying the human form that would be instantly recognizable to an Athenian of the 5th century BC.

Popular Works:

- Primavera (The Birth of Spring), Birth of Venus - Sandro Botticelli

- Bronze David, Marble David - Donatello

- David, Pieta' - Michelangelo

- School of Athens - Raphael

- Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore, Ospedale degli Innocenti Loggia, San Lorenzo (Florence), Santo Spirito (Florence) - Brunelleschi

- Mona Lisa, The Last Supper, Vitruvian Man, Annunciation - Leonardo

- North and East Doors, Baptistry of San Giovanni, Florence - Ghiberti

Themes: This period is characterized by numerous religious works; themes include the Holy Trinity, Holy Family, Adoration of the Magi, Virgin and child. Mythological subject matter is introduced in the visual arts of this period.

Centers of Art:

- 15th-century Florence

- 16th-century Rome

- 16th-century Northern Italy (including Venice, provinces)

- 15th-century Flanders

Important literature:

- Vasari's Lives of the Artists

- Alberti's On Painting

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Leonardo Da Vinci

[edit | edit source]-

Vitruvian Man

-

The Last Supper

-

Annunciation

-

Mona Lisa

-

Lady with an Ermine

-

Salvator Mundi

Michelangelo

[edit | edit source]-

David

-

Pieta

-

Creation of Adam

-

Sistine Chapel ceiling.

Dutch Golden Age

[edit | edit source]Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn

[edit | edit source]-

The Storm on the Sea of Galilee by Rembrandt - 1633.

-

The Blinding of Samson by Rembrandt - 1636.

-

The Night Watch by Rembrandt - 1642.

-

Self-Portrait with Beret and Turned-Up Collar by Rembrandt - 1659.

Johannes Vermeer

[edit | edit source]-

The Wine Glass by Johannes Vermeer - 1658 - 1660.

-

The Milkmaid by Johannes Vermeer - 1658 - 1661.

-

Girl with a Pearl Earring by Johannes Vermeer - 1665

Other Notable Works

[edit | edit source]-

Primavera by Sandro Botticelli - 1470s-1480s. An example of Italian Renaissance panel painting.

-

Delivery of the Keys an example of Italian Renaissance painting by Pietro Perugino - 1481-1482

-

The Triumph of Death by Pieter Bruegel the Elder - 1562.

-

The Wedding Feast at Cana by Paolo Veronese - 1563

-

The Dispute of Minerva and Neptune by René-Antoine Houasse - 1689.

17th Century

As the Renaissance occurred in Europe, the art world of other countries did not stay stagnant.

Gallery

[edit | edit source]-

The Taj Mahal in India.

18th Century

Baroque

[edit | edit source]Spilling over into the beginning of the 18th century were the last remnants of Baroque art. Baroque interior design, in particular, is distinctly ornate and rich in ceiling decor.

Rococo

[edit | edit source]Following Baroque art, a similar movement, called Rococo, developed. Initially, it thrived in interior design as Baroque had previously done, but in comparison to interior design done in the Baroque style, the Rococo style could be described as softer and more refined.

The main proponents of Rococo style painting were Antoine Watteau, Francois Boucher, and Jean-Honore Fragonard. Rococo painting has a very distinct style. Light, mint greens and soft pinks and blues were some of the most popularly used colors. In general, the color palette consisted of soft, yet intense, colors. Also, distinct to Rococo painting was the light subject matter; generally paintings in this style depicted the leisure of the upper class. Jean-Honore Fragonard's The Swing exemplifies the Rococo style, as seen in painting.

Enlightment

[edit | edit source]The Rococo movement came to an end with the onset of the Enlightenment, which ushered in the next major artistic movement-Neoclassicism. As the name suggest, a revival of the influence of classic art from ancient Greece and Rome ensued. In painting, Jaques-Louis David was the leading painter of this style. His works, such as the Oath of the Horatii exemplified Neoclassicism with its logical order and stately, even heroic, subject matter. In architecture, one of the greatest influences was Palladio's Villa Rotunda, a Renaissance building, itself, inspired by classic order and symmetry.

As demonstrated by the shift from Rococo to Neoclassicism, two starkly contrasting art styles, many successive art movements are reactions to previous styles. The very formal, stately Neoclassical style was a direct reaction to that of the previous light and airy Rococo style.

Gallery

[edit | edit source]European

[edit | edit source]-

Interior of Ca' Rezzonico in Venice, an example of Rococo artwork. - 1753

-

View of Warsaw from the Terrace of the Royal Castle by Bernardo Bellotto - 1773.

-

David - Oath of the Horatii - 1784

-

David - The Death of Socrates - 1787

-

Jacques-Louis David - Portrait d'Henriette de Verninac - 1799

Japanese

[edit | edit source]-

Three Beauties of the Present Day by Kitagawa Utamaro - 1793. An example of nishiki-e color woodblock print.

Architecture

[edit | edit source]-

Amber Room - 1701.

-

Monticello - 1772.

-

Panthéon - 1790.

-

Brandenburg Gate Neoclassical architecture - 1788-1791.

19th Century

Impressionism

[edit | edit source]Photography in the nineteenth century both challenged painters to be true to nature and encouraged them to exploit aspects of the painting medium, like color, that photography lacked. This divergence away from photographic realism appears in the work of a group of artists who from 1874 to 1886 exhibited together, independently of the Salon. The leaders of the independent movement were Claude Monet, August Renoir, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, and Mary Cassatt. They became known as Impressionists because a newspaper critic thought they were painting mere sketches or impressions. The Impressionists, however, considered their works finished. Many Impressionists painted pleasant scenes of middle class urban life, extolling the leisure time that the industrial revolution had won for middle class society. In Renoir's luminous painting Luncheon of the Boating Party, for example, young men and women eat, drink, talk, and flirt with a joy for life that is reflected in sparkling colors. The sun filtered through the orange striped awning colors everything and everyone in the party with its warm light. The diners' glances cut across a balanced and integrated composition that reproduces a very delightful scene of modem middle class life.

Since they were realists, followers of Courbet and Manet, the Impressionists set out to be "true to nature," a phrase that became their rallying cries. When Renoir and Monet went out into the countryside in search of subjects to paint, they carried their oil colors, canvas, and brushes with them so that they could stand right on the spot and record what they saw at that time. In contrast, most earlier landscape painters worked in their studio from sketches they had made outdoors. The more an Impressionist like Monet looked, the more she or he saw. Sometimes Monet came back to the same spot at different times of day or at a different time of year to paint the same scene. In 1892 he rented a room opposite the Cathedral of Rouen in order to paint its facade over and over again. He never copied himself because the light and color always changed with the passage of time, and the variations made each painting a new creation. The differences are obvious when we compare the painting of Rouen Cathedral that is now in Switzerland with the one that is now in Washington, D.C. Realism meant to an Impressionist that the painter ought to record the most subtle sensations of reflected light. In capturing a specific kind of light, this style conveys the notion of a specific and fleeting moment of time. Impressionist painters like Monet and Renoir recorded each sensation of light with a touch of paint in a little stroke like a comma. The public back then was upset that Impressionist paintings looked like a sketch and did not have the polish and finish that more fashionable paintings had. But applying the paint in tiny strokes allowed Monet, Renoir, or Cassatt to display color sensations openly, to keep the colors unmixed and intense, and to let the viewer's eye mix the colors. The bright colors and the active participation of the viewer approximated the experience of the scintillation of natural sunlight. The Impressionists remained realists in the sense that they remained true to their sensations of the object, although they ignored many of the old conventions for representing the object "out there." But truthfulness for the Impressionists lay in their personal and subjective sensations not in the "exact" reproduction of an object for its own sake. The objectivity of things existing outside and beyond the artist no longer mattered as much as it once did. The significance of "outside" objects became irrelevant. Concern for representing an object faded, while concern for representing the subjective grew. The focus on subjectivity intensified because artists became more concerned with the independent expression of the individual. Reality became what the individual saw. With Impressionism, the meaning of realism was transformed into subjective realism, and the subjectivity of modem art was born.

Artists

[edit | edit source]- Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875)

- Charles-François Daubigny (1817-1878)

- Gustave Courbet (1819-1877)

- Eugene Boudin (1824-1898)

- #Camille Pissarro (1830-1903)

- Camille Pissarro (1830-1903)

- Edouard Manet (1832-1883)

- Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

- Claude Monet (1840-1926)

- Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919)

- Frederic Bazille (1841-1870)

- Berthe Morisot (1841-1895)

- Mary Cassatt (1844-1926)

- Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894)

- Paul Gauguin (1848-1903)

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903)

[edit | edit source]Born July 10, 1830 in St. Thomas, Virgin Islands. His father, a Portuguese Jew, ran a general store. Although Pissarro attended school in Paris and demonstrated an exceptional talent for drawing, he returned to St. Thomas in 1847 to work in the family business. During the ensuing years his interest in art persisted, and in 1855 his parents finally yielded to his ambition to become a painter.

Pissarro reached Paris in time to see the important World's Fair of 1855. He was particularly impressed by the landscapes of Camille Corot and other members of the Barbizon group, who had taken the first steps toward working directly from nature, and by the ambitious and forthright realism of Gustave Courbet, although his own work increasingly gravitated toward landscape rather than figurative subjects.

During the next 10 years, Pissarro received some academic training at the École des Beaux-Arts, but he spent most of his time at the Académie Suisse, where free classes were offered. This was an important gathering place for those artists whose ambitions and sensibilities lay outside the teaching of the official schools, for it offered greater opportunity to discuss and develop personal ideas about painting and art in general. In this setting Pissarro became friends with Claude Monet, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Paul Cézanne, who were seeking alternatives to the established methods of painting. Pissarro's works at this time were occasionally, though by no means consistently, accepted at the annual Salons. More importantly, however, he received critical backing and encouragement from the journalist and critic Émile Zola.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-7, Pissarro and Monet went to London, where they were impressed by the landscape paintings of John Constable and J.M.W. Turner. By this time Pissarro and Monet had begun to work directly from nature and to develop the unique style that would later be called Impressionism. In their pursuit of this new and revolutionary direction, the lessons of the earlier English landscapists provided crucial and much-needed support, particularly in terms of the loose handling of paint, the abstractness, and the strong response to nature that characterized their own paintings. When Pissarro returned to his home at Louveciennes near Paris, he found that the Prussians had destroyed nearly all of his paintings.

By the early 1870s, the work of Pissarro and his colleagues had been rejected by the Salon, France's official state-run art show, on repeated occasions. In 1874, they held their own exhibition, a show of "independent" artists, which included the work of Pissarro, Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Edgar Degas, and Berthe Morisot. This was the first Impressionist exhibition (the term "Impressionist," originally used derisively, was actually coined by a newspaper critic). There were seven similar exhibitions from 1874-86, and Pissarro was the only artist who participated in all eight. This fact is important because it reveals something about Pissarro's relation to Impressionism generally: he was the patriarch and teacher of the movement, constantly advising younger artists, introducing them to one another, and encouraging them to join the revolutionary trend that he helped to originate. In 1892, a large retrospective of Pissarro's work finally brought him the international recognition he deserved. Characteristic paintings are Path through the Fields (1879), Landscape, Eragny (1895), and Place du Théâtre Français (1898). He died in Paris on November 12, 1903. Although his work was generally less innovative than that of his major contemporaries, his contributions as an artist should not be underestimated in the development of the Impressionist painting style.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

[edit | edit source]Born Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas on July 19, 1834, in Paris, France. A member of an upper-class family (his father was a banker), Degas was originally intended to practice law, which he studied for a time after finishing secondary school. In 1855, however, he enrolled at the famous École des Beaux-Arts, or School of Fine Arts, in Paris, where he studied under Louis Lamothe, a pupil of the classical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. In order to supplement his art studies, Degas traveled extensively, including trips to Naples, Florence, and Rome (where he lived for three years), in order to observe and copy the works of such Renaissance masters as Sandro Botticelli, Andrea Mantegna, and Nicolas Poussin. From his early classical education, Degas learned a good deal about drawing figures, a skill he used to complete some impressive family portraits before 1860, notably The Belleli Family (1859). In 1861, Degas returned to Paris, where he executed several "history paintings," or works with historical or Biblical themes, which were then the most sought-after paintings by serious art patrons and particularly the prestigious state-run art show, the Salon, held each year in Paris. He also began copying works by the Old Masters from the Louvre, which he would continue doing for many years. With his historical paintings (including 1861's Daughter of Jephthah, based on an incident from the Old Testament) and his finely-wrought portraits of friends, family members, and clients, the young Degas quickly established a reputation among French art circles and never suffered from the financial problems that plagued many of his contemporaries.

Soon, however, Degas began to shift his focus from historical painting to depictions of life in contemporary Paris. By 1862, he had begun painting various scenes from the racecourse, including studies of the horses, their mounts, and the fashionable spectators. Degas' style after the early 1860s was influenced by the budding Impressionist movement, including his friendship with Édouard Manet, as well as his introduction to Japanese graphic art, with its striking representation of figures. Along with his work painting scenes from the racetrack, Degas began concentrating on portraits of groups, most notably of female ballet dancers, who became Degas' most famous subjects. Degas served in the artillery division of the French National Guard during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. Upon his return, he worked on even more ambitious studies of groups, often in motion, in both indoor and outdoor settings. In October 1872, Degas visited the United States for five months, spending time in New Orleans, Louisiana, where some members of his family were in the cotton business. From this experience came his famous painting New Orleans Cotton Office (1873).

Many of Degas' paintings featured the artist's experiments with unorthodox visual angles and asymmetrical perspectives, somewhat like a photographer's treatment of a subject. Examples of this style are A Carriage at the Races (1872), which features a human figure who is almost cut in half by the edge of the canvas, and Ballet Rehearsal (1876), a group portrait of ballerinas that appears almost cropped at the edges. From 1873 to 1883, Degas produced many of his most famous works, both paintings and pastels, of his favorite subjects, including the ballet, the racecourse, the music hall, and café society. Though he never suffered from lack of money or interest in his work, Degas stopped exhibiting at the Salon in 1874, and thereafter displayed most of his works alongside those of the other Impressionists, including Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, Berthe Morisot, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro. His strong focus on draftsmanship, portraiture, and composition distanced him from the rest of the artists identified as Impressionists.

Sometime in the 1870s, Degas began to suffer a loss of vision, which limited his ability to work. He began increasingly to work as a sculptor, producing bronze statues of horses and ballet dancers, among other subjects. A number of his sculptures, including Little Dancer Aged Fourteen (1880-81), were figures dressed in real costumes, and many of them captured the moment of transition between one position to another, giving the statues a real sense of immediacy and motion. As Degas' eyesight grew worse, he became an increasingly reclusive and eccentric figure. In the last years of his life, he was almost totally blind. Edgar Degas died on September 27, 1917, in Paris, leaving behind in his studio an important collection of drawings and paintings by his contemporaries as well as a number of statues crafted in wax and metal, which were cast in bronze after his death.

Claude Monet (1840-1926)

[edit | edit source]Born November 14, 1840, in Paris, France. Claude Monet was a seminal figure in the evolution of Impressionism, a pivotal style in the development of modern art. In 1845 his family moved to Le Havre, and by the time he was 15, Monet had developed a local reputation as a caricaturist. Through an exhibition of his caricatures in 1858, Monet met Eugène Boudin, a landscape painter who exerted a profound influence on the young artist. Boudin introduced him to outdoor painting, an activity that he entered reluctantly but which soon became the basis for his life's work. By 1859 Monet was determined to pursue an artistic career. He visited Paris and was impressed by the paintings of Eugène Delacroix, Charles Daubigny, and Camille Corot. Against his parents' wishes, Monet decided to stay in Paris. He worked at the free Académie Suisse, where he met Camille Pissarro, and he frequented the Brasserie des Martyrs, a gathering place for Gustave Courbet and other realists who constituted the vanguard of French painting in the 1850s. Formative Period

Monet's studies were interrupted by military service in Algeria from 1860 to 1862. The remainder of the decade witnessed constant experimentation, travel, and the formation of many important artistic friendships. In 1862, he entered the studio of Charles Gleyre in Paris and met Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille. During 1863 and 1864, he periodically worked in the forest at Fontainebleau with the Barbizon artists Théodore Rousseau, Jean François Millet, and Daubigny, as well as with Corot. In Paris in 1869, he frequented the Café Guerbois, where he met Édouard Manet. At the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, Monet traveled to London, where he met the adventurous and sympathetic dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. The following year Monet and his wife, Camille, whom he had married in 1870, settled at Argenteuil, which became a semi-permanent home (he continued to travel throughout his life) for the next six years. Monet's constant movements during this period were directly related to his artistic ambitions. The phenomena of natural light, atmosphere, and color captivated his imagination, and he committed himself to an increasingly accurate recording of their enthralling variety. He consciously sought that variety and gradually developed a remarkable sensitivity for the subtle particulars of each landscape he encountered. Paul Cézanne is reported to have said, "Monet is the most prodigious eye since there have been painters." Relatively few of Monet's canvases from the 1860s have survived. Throughout the decade, and during the 1870s as well, he suffered from extreme financial hardship and frequently destroyed his own paintings rather than have them seized by creditors. A striking example of his early style is Terrace at Sainte-Adresse (1867). The painting contains a shimmering array of bright, natural colors, eschewing completely the somber browns and blacks of the earlier landscape tradition.

Monet and Impressionism

[edit | edit source]As William Seitz wrote in 1960, "The landscapes Monet painted at Argenteuil between 1872 and 1877 are his best-known, most popular works, and it was during these years that Impressionism most closely approached a group style. Here, often working beside Renoir, Sisley, Caillebotte, or Manet, he painted the sparkling impressions of French river life that so delight us today." During these same years, Monet exhibited regularly in the Impressionist group shows, the first of which took place in 1874. On that occasion his painting Impression: Sunrise (1872) inspired a hostile newspaper critic to call all the artists "Impressionists," and the designation has persisted to the present day.

Monet's paintings from the 1870s reveal the major tenets of the Impressionist vision. Along with Impression: Sunrise, Red Boats at Argenteuil (1875) is an outstanding example of the new style. In these paintings, Impressionism is essentially an illusionist style, albeit one that looks radically different from the landscapes of the Old Masters. The difference resides primarily in the chromatic vibrancy of Monet's canvases. Working directly from nature, he and the other Impressionists discovered that even the darkest shadows and the gloomiest days contain an infinite variety of colors. To capture the fleeting effects of light and color, however, Monet gradually learned that he had to paint quickly and to employ short brushstrokes loaded with individualized colors. This technique resulted in canvases that were charged with painterly activity; in effect, they denied the even blending of colors and the smooth, enameled surfaces to which earlier painting had persistently subscribed.

Yet, in spite of these differences, the new style was illusionistically intended; only the interpretation of what illusionism consisted of had changed. For traditional landscape artists, illusionism was conditioned first of all by the mind: that is, painters tended to depict the individual phenomena of the natural world-leaves, branches, blades of grass-as they had studied them and conceptualized their existence. Monet, on the other hand, wanted to paint what he saw rather than what he intellectually knew. And he saw not separate leaves, but splashes of constantly changing light and color. According to Seitz, "It is in this context that we must understand his desire to see the world through the eyes of a man born blind who had suddenly gained his sight: as a pattern of nameless color patches." In an important sense, then, Monet belongs to the tradition of Renaissance illusionism: in recording the phenomena of the natural world, he simply based his art on perceptual rather than conceptual knowledge.

During the 1880s, the Impressionists began to dissolve as a cohesive group, although individual members continued to see one another and they occasionally worked together. In 1883 Monet moved to Giverny, but he continued to travel-to London, Madrid, and Venice, as well as to favorite sites in his native country. He gradually gained critical and financial success during the late 1880s and the 1890s. This was due primarily to the efforts of Durand-Ruel, who sponsored one-man exhibitions of Monet's work as early as 1883 and who, in 1886, also organized the first large-scale Impressionist group show to take place in the United States.

Monet's painting during this period slowly gravitated toward a broader, more expansive and expressive style. In Spring Trees by a Lake (1888) the entire surface vibrates electrically with shimmering light and color. Paradoxically, as his style matured and as he continued to develop the sensitivity of his vision, the strictly illusionistic aspect of his paintings began to disappear. Plastic form dissolved into colored pigment, and three-dimensional space evaporated into a charged, purely optical surface atmosphere. His canvases, although invariably inspired by the visible world, increasingly declared themselves as objects that are, above all, paintings. This quality links Monet's art more closely with modernism than with the Renaissance tradition.

Modernist, too, are the "serial" paintings to which Monet devoted considerable energy during the 1890s. The most celebrated of these series are the haystacks (1891) and the façades of Rouen Cathedral (1892-1894). In these works Monet painted his subjects from more or less the same physical position, allowing only the natural light and atmospheric conditions to vary from picture to picture. That is, he "fixed" the subject matter, treating it like an experimental constant against which changing effects could be measured and recorded. This technique reflects the persistence and devotion with which Monet pursued his study of the visible world. At the same time, the serial works effectively neutralized subject matter per se, implying that paintings could exist without it. In this way his art established an important precedent for the development of abstract painting.

Late Work

[edit | edit source]Monet's wife died in 1879; in 1892 he married Alice Hoschedé. By 1899 his financial position was secure, and he began work on his famous series of water lily paintings. Water lilies existed in profusion in the artist's exotic gardens at Giverny, and he painted them tirelessly until his death there on December 5, 1926. Monet's late years were by no means easy. During his last two decades, he suffered from poor health and had double cataracts; by the 1920s, he was virtually blind. In addition to his physical ailments, Monet struggled desperately with the problems of his art. In 1920, he began work on 12 large canvases (each measuring 14 feet in width) of water lilies, which he planned to give to the state. To complete them, he fought against his own failing eyesight and against the demands of a large-scale mural art for which his own past had hardly prepared him. In effect, the task required him to learn a new kind of painting at the age of 80. The paintings are characterized by a broad, sweeping style; virtually devoid of subject matter, their vast, encompassing spaces are generated almost exclusively by color. Such color spaces were without precedent in Monet's lifetime; and moreover, their descendants have appeared in contemporary painting only since the end of World War II.

Berthe Morisot (1841-1895)

[edit | edit source]

Born January 14, 1841, in Bourges, France. The daughter of a high-ranking government official and granddaughter of the influential Rococo painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Morisot began studying painting alongside her sister Edma when both were young. Though women were not allowed to join official arts institutions, like schools, until the last few years of the nineteenth century, Morisot and her sister earned a certain measure of respect within art circles for their budding talent. After copying masterpieces from the Louvre Museum in the late 1850s under Joseph Guichard, Berthe and Edma began painting outdoor scenes while studying with the well-known landscape painter Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot. Berthe Morisot worked with Corot, who became a family friend, from 1862 to 1868. She first exhibited her paintings at the prestigious state-run art show, the Salon, in 1864, and her work was shown there regularly for the next decade..

Morisot was greatly influenced by her friendship with Édouard Manet, to whom she was introduced in 1868 by their fellow artist Henri Fantin-Latour. Though Morisot was never a pupil of Manet's, she soon abandoned aspects of Corot's teachings and destroyed almost all of her early work in favor of a more unconventional and modern approach, with the encouragement of Manet and others, including Edgar Degas and Frédéric Bazille. She also played an important role in Manet's career, posing for a number of his paintings-notably The Balcony (1869) and Repose (c. 1870) - and encouraging him to adapt some tenets of Impressionism into his work.

Beginning in 1874, Morisot refused to show her work at the Salon, choosing to join a fledgling group of Impressionist painters that included Degas, who would become Morisot's lifelong friend, as well as Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, and Alfred Sisley. Morisot agreed to take part in the first independent exhibition of Impressionist paintings, which opened in a photographer's studio on Paris's Boulevard des Capucines in April 1874. In doing so, she went against the advice of Édouard Manet, who refused to exhibit with the Impressionists and was determined to make his name at the Salon. Among the paintings she showed at the exhibition were The Cradle, The Harbor at Cherbourg, Hide and Seek, and Reading.

In December 1874, at the age of 33, Morisot married Manet's younger brother, Eugène, also a painter. Eugène Manet supported his wife in her work and the marriage gave Morisot social and financial stability while she continued her painting career. On a census form, Morisot famously recorded herself as "without profession," underscoring her vision of her life and work within, not outside of, the traditional feminine sphere. She participated in all of the Impressionist exhibitions save one, in 1877, when she was pregnant with her daughter, Julie, born in 1878.

Morisot painted in oils, watercolors, and pastels, and produced numerous drawings. Her wide range of subjects included portraits (many of her sister Edma), landscapes, still lives, and the domestic scene, particularly traditional feminine occupations. A particularly notable example of the latter was Woman at Her Toilette (c. 1879), which she displayed in the fifth Impressionist exhibition in 1880. For some of her later works, Morisot noticeably changed her style, making numerous sketches of a subject before beginning a painting rather than relying on spontaneous observation, as in her earlier work. Paintings that showcased her new style included The Cherry Tree (1891-92) and Girl with a Greyhound (1893). Eugène Manet died in April 1892, after a long illness. Morisot's friends and fellow artists rallied around her and her young daughter Julie, and she continued to work. Though never commercially successful during her lifetime, Morisot outsold several of her fellow Impressionists, including Monet, Renoir, and Sisley. She had her first solo exhibition in 1892 at the Boussod and Valadon gallery, where she sold a number of works, and she earned further recognition in 1894, when the French government purchased her oil painting Young Woman in a Ball Gown. In the winter of 1894-95, Morisot contracted pneumonia. She died on March 2, 1895, at the age of 54. After her death, Renoir and Degas organized a retrospective of her work, which garnered serious critical acclaim and ensured her place in art history as one of the founding members of the revolutionary Impressionist movement.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919)

[edit | edit source]Born February 25, 1841, in Limoges, France. Shortly after his birth, his family moved to Paris. Because he showed a remarkable talent for drawing, Renoir became an apprentice in a porcelain factory, where he painted plates. Later, after the factory had gone out of business, he worked for his older brother, decorating fans. Throughout these early years, Renoir made frequent visits to the Louvre, where he studied the art of earlier French masters, particularly those of the 18th century-Antoine Watteau, François Boucher, and Jean Honoré Fragonard. His deep respect for these artists informed his own painting throughout his career. During the 1870s, a revolution erupted in French painting. Encouraged by artists like Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet, a number of young painters began to seek alternatives to the traditions of Western painting that had prevailed since the beginning of the Renaissance. These artists went directly to nature for their inspiration and into the actual society of which they were a part. As a result, their works revealed a look of freshness and immediacy that in many ways departed from the look of Old Master painting. The new art, for instance, displayed vibrant light and color instead of the somber browns and blacks that had dominated previous painting. These qualities, among others, signaled the beginning of modern art.

Early Career

[edit | edit source]In 1862, Renoir decided to study painting seriously and entered the Atelier Gleyre, where he met Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, and Jean Frédéric Bazille. During the next six years, Renoir's art showed the influence of Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet, the two most innovative painters of the 1850s and 1860s. Courbet's influence is especially evident in the bold palette-knife technique of Diane Chasseresse (1867), while Manet's can be seen in the flat tones of Alfred Sisley and His Wife (1868). Still, both paintings reveal a sense of intimacy that is characteristic of Renoir's personal style.

The 1860s were difficult years for Renoir. At times he was too poor to buy paints or canvas, and the Salons of 1866 and 1867 rejected his works. The following year the Salon accepted his painting Lise. He continued to develop his work and to study the paintings of his contemporaries-not only Courbet and Manet, but Camille Corot and Eugène Delacroix as well. Renoir's indebtedness to Delacroix is apparent in the lush painter like that of the Odalisque (1870). Renoir and Impressionism In 1869, Renoir and Monet worked together at La Grenouillère, a bathing spot on the Seine. Both artists became obsessed with painting light and water. According to Phoebe Pool (1967), this was a decisive moment in the development of Impressionism, for "It was there that Renoir and Monet made their discovery that shadows are not brown or black but are colored by their surroundings, and that the 'local color' of an object is modified by the light in which it is seen, by reflections from other objects and by contrast with juxtaposed colors." The styles of Renoir and Monet were virtually identical at this time, an indication of the dedication with which they pursued and shared their new discoveries. During the 1870s, they still occasionally worked together, although their styles generally developed in more personal directions. In 1874, Renoir participated in the first Impressionist exhibition, along with Monet, Edgar Degas, Alfred Sisley, Camille Pissarro, and Berthe Morisot. His works included The Opera Box (1874), a painting that shows the artist's penchant for rich and freely handled figurative expression. Of all the Impressionists, Renoir most consistently and thoroughly adapted the new style-in its inspiration, essentially a landscape style-to the great tradition of figure painting.

Although the Impressionist exhibitions were the targets of much public ridicule during the 1870s, Renoir's patronage gradually increased during the decade. He became a friend of Caillebotte, one of the first patrons of the Impressionists, and he was also backed by the art dealer Durand-Ruel and by collectors like Victor Choquet, the Charpentiers, and the Daidets. The artist's connection with these individuals is documented by a number of handsome portraits, for instance, Madame Charpentier and Her Children (1878).

In the 1870s, Renoir also produced some of his most celebrated Impressionist genre scenes, including The Swing and The Ball at the Moulin de la Galette (both 1876). These works embody his most basic attitudes about art and life. They show men and women together, openly and casually enjoying a society diffused with warm, radiant sunlight. Figures blend softly into one another and into their surrounding space. Such worlds are pleasurable, sensuous, and generously endowed with human feeling.

Renoir's "Dry" Period

[edit | edit source]During the 1880s, Renoir gradually separated himself from the other Impressionists, largely because he became dissatisfied with the direction the new style was taking in his own hands. In paintings like The Luncheon of the Boating Party (1881), he felt that his style was becoming too loose, that forms were losing their distinctiveness and sense of mass. As a result, he looked to the past for a fresh inspiration. In 1881, he traveled to Italy and was particularly impressed by the art of Raphael. During the next six years, Renoir's paintings became increasingly dry: he began to draw in a tight, classical manner, carefully outlining his figures in an effort to give them plastic clarity. The works from this period, such as The Umbrellas (1883) and Les grandes baigneuses (1884-1887), are generally considered the least successful of Renoir's mature expressions. Their classicizing effort seems self-conscious, a contradiction to the warm sensuality that came naturally to him.

Late Career

[edit | edit source]By the end of the 1880s, Renoir had passed through his dry period. His late work is truly extraordinary: a glorious outpouring of monumental nude figures, beautiful young girls, and lush landscapes. Examples of this style include The Music Lesson (1891), Young Girl Reading (1892), and Sleeping Bather (1897). In many ways, the generosity of feeling in these paintings expands upon the achievements of his great work in the 1870s. Renoir's health declined severely in his later years. In 1903, he suffered his first attack of rheumatoid arthritis and settled for the winter at Cagnes-sur-Mer. By this time he faced no financial problems, but the arthritis made painting painful and often impossible. Nevertheless, he continued to work, at times with a brush tied to his crippled hand. Renoir died at Cagnes-sur-Mer on December 3, 1919, but his death was preceded by an experience of supreme triumph: the state had purchased his portrait Madame Georges Charpentier (1877), and he traveled to Paris in August to see it hanging in the Louvre.

Edouard Manet (1832-1883)

[edit | edit source]Born January 23, 1832 in Paris, France, to Auguste Édouard Manet, an official at the Ministry of Justice, and Eugénie Désirée Manet. Manet's father, who had expected his son to study law, vigorously opposed his wish to become a painter. The career of naval officer was decided upon as a compromise, and at the age of 16 Édouard sailed to Rio de Janeiro on a training vessel. Upon his return he failed to pass the entrance examination of the naval academy. His father relented, and in 1850 Manet entered the studio of Thomas Couture, where, in spite of many disagreements with his teacher, he remained until 1856. During this period, Manet traveled abroad and made numerous copies after the Old Masters in both foreign and French public collections. Early Works Manet's entry for the Salon of 1859, The Absinthe Drinker, a thematically romantic but conceptually daring work, was rejected. At the Salon of 1861, his Spanish Singer, one of a number of works of Spanish character painted in this period, not only was admitted to the Salon but won an honorable mention and the acclaim of the poet Théophile Gautier. This was to be Manet's last success for many years.

In 1863, Manet married Suzanne Leenhoff, a Dutch pianist. That year he showed 14 paintings at the Martinet Gallery; one of them, Music in the Tuileries, remarkable for its freshness in the handling of a contemporary scene, was greeted with considerable hostility. Also in 1863, the Salon rejected Manet's large painting Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe, or Luncheon on the Grass, and the artist elected to have it shown at the now famous Salon des Refusés, created by the emperor under the pressure of the exceptionally large number of painters whose work had been turned away. Here, Manet's picture attracted the most attention and brought forth a kind of abusive criticism that was to set a pattern for years to come.

In 1865, Manet's Olympia produced a still more violent reaction at the official Salon, and his reputation as a renegade became widespread. Upset by the criticism, Manet made a brief trip to Spain, where he admired many works by Diego Velázquez, to whom he referred as "the painter of painters."

Support of Baudelaire and Zola

[edit | edit source]Manet's close friend and supporter during the early years was Charles Baudelaire, who, in 1862, had written a quatrain to accompany one of Manet's Spanish subjects, Lola de Valence, and the public, largely as a result of the strange atmosphere of the Olympia, linked the two men readily. In 1866, after the Salon jury had rejected two of Manet's works, Émile Zola came to his defense with a series of articles filled with strongly expressed, uncompromising praise. In 1867, he published a book that contains the prediction, "Manet's place is destined to be in the Louvre." This book appears on Zola's desk in Manet's portrait of the writer (1868). In May of that year, the Paris World's Fair opened its doors, and Manet, at his own expense, exhibited 50 of his works in a temporary structure, not far from Gustave Courbet's private exhibition. This was in keeping with Manet's view, expressed years later to his friend Antonin Proust, that his paintings must be seen together in order to be fully understood.

Although Manet insisted that a painter be "resolutely of his own time" and that he paint what he sees, he nevertheless produced two important religious works, Dead Christ with Angels and Christ Mocked by the Soldiers, which were shown at the Salons of 1864 and 1865, respectively, and ridiculed. Only Zola could defend the former work on the grounds of its vigorous realism while playing down its alleged lack of piety. It is also true that although Manet despised the academic category of "history painting" he did paint the contemporary Naval Battle between the Kearsarge and the Alabama (1864) and The Execution of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico (1867). The latter is based upon a careful gathering of the facts surrounding the incident and composed, largely, after Francisco Goya's Executions of the Third of May, resulting in a curious amalgam of the particular and the universal. Manet's use of older works of art in elaborating his own major compositions has long been, and continues to be, a problematic subject, since the old view that this procedure was needed to compensate for the artist's own inadequate imagination is rapidly being discarded.

Late Works