Cataloging and Classification/Cataloging

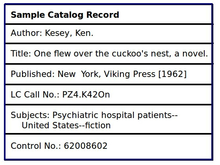

Cataloging is an essential task in library science. A cataloger organizes the materials within a library, in modern times into an computerized database that functions as the library catalog. Put simply, catalogers create a record for each item that describes subject, author, title, and many other identifying information. They then classify the item by adding a call number to it, which helps both patrons and staff to find the items on the shelves in its respective subject area.

Every institution that has a collection, especially libraries, need to have their collections categorized. Every physical information resource that gets added to the collection needs to undergo the procedure of the institution collection, which includes examination, cleaning, preserving, categorizing, adding labels, covers, and so on, and finally being situated on the shelves.

The catalog is the primary means of access to the collections. Once cataloging is going done, there are two outcomes:

- The collections are arranged in order.

- The catalog is created (if not already done) and made up to date.

Definition

[edit | edit source]Cataloging (alternative spelling: cataloguing) is defined in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary as a transitive verb "catalog" as follows:[1]

- "to classify (something, such as books or information) descriptively".

Functionally, cataloging may be considered as the process of creating metadata representing information resources, such as books, sound recordings, moving images, etc., and storing the metadata in an appropriate manner in a bibliographic system.

Purpose of cataloging

[edit | edit source]

Charles Ammi Cutter (1837–1903), a prominent American librarian stated that the purpose of a catalog was:[2]

- 1.To enable a person to find a book when either of the following is known:

- (a) the author

- (b) the title

- (c) the subject.

- 2.To show what the library has:

- (a) by a given author

- (b) on a given subject

- (c) in a given kind of literature.

- 3.To assist in the choice of a book:

- (a) as to the edition (bibliographically)

- (b) as to its character (literary or topical).

Basically, while Cutter's above statement is still valid today, in the modern context, the purpose and scope of cataloging goes beyond this.

From the point of view of the user, the purposes of cataloging of information in general, including resources for libraries, galleries, museums and archives, are:[note 1][3]

- Find - to search for resources (say, a book) that match specific criteria.

- Identify - to confirm that a resource corresponds the one sought; to tell similar items apart.

- Select - to choose a form of the resource (say, a spoken audio book) that is appropriate to the user’s needs.

- Obtain - to gain access to the resource (form) described.

- Explore - to discover resources and to gain insight into the variety of resources available that meet the need or criteria.

All this effort is undertaken by the library because it gives them benefits. The physical significance or outcome of cataloging in a library or collection is:[4]

- To classify a collection initially and provide a process by which new items are added only after undergoing the cataloging process.

- To create the necessary means of locating and accessing resources in the collection.

- To provide for a scheme of arrangement and storage of the collection.

- The creation and maintenance of the physical or online catalog for the collection or institution.

Types of Cataloging

[edit | edit source]

There are two kinds of cataloging. Each have a different purpose, philosophy, procedures and standards. They are:

Both systems will be discussed in much detail later.

Descriptive Cataloging

[edit | edit source]Joudrey et al. (2015) define descriptive cataloging as:[5]

- "the makeup of an information resource and identifies those entities responsible for its intellectual and/or artistic contents without reference to its classification by subject or to the assignment of subject headings, both of which are the province of subject cataloging."

Subject cataloging

[edit | edit source]Subject cataloging, the second major component of library cataloging, entails two key activities: conceptual analysis and translation. Conceptual analysis is the process of determining subject matter of a resource, i.e., what a resource is about. Translation is the process of transforming the information regarding what a resource is about into terms chosen from strictly controlled lists.[6]

For fully functional cataloging to be achieved, libraries also need to incorporate a subjective classification system in their scheme of cataloguing.

Classification systems are systems of organization which specify how the library resources are arranged and ordered systematically. Based on how they are constructed, library classification systems facilitate subject access by allowing the user to find out what resources the library has on a certain subject. Secondly, they also provide a known location for the information source to be located (e.g. where it is shelved). Examples of general classification system are the Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC), the Universal Decimal Classification (UDC) and the Library of Congress Classification.

Besides this, there are special-purpose classification systems in use also, such as the Dickinson classification (music), or the NLM Classification (medicine).

These will be discussed in greater detail later in the textbook.

Simple cataloging

[edit | edit source]

The simplest way to physically catalog a collection is to write the required attributes of metadata of each resource item (such as title, author, publisher, and year of publication, etc.) in a register. This can be done in line-wise entries for a book or in the form of a table with columns.

At this stage, the cataloguer needs to give a unique number to each item in the collection. This is known as an accession number. The accession number is a unique identifier assigned to each and every acquired resource (book, etc.), and allows us to track and manage that resource, i.e. we achieve "control" over that resource. Contrary to the name, an accession number does not need to be a number, in most collections, accession numbers are alphanumeric.

In the past, when there were no modern electronic aids and even printing was not feasible, the details of each resource in the collection were hand-written on small cards which were kept sorted in drawers of specially made cupboards; such a catalog was referred to as a card catalog.

In the case of some collections, the details of each resource were sometimes printed and bound as books (as in the case of a concordance for a museum).

Development of Modern Cataloging

[edit | edit source]With the explosion of the publishing industry and the size of libraries, it was laborious for each library to create the bibliographic records. Book publishers began providing the bibliographic information within the books on the copyright page. At first, the classification information in a book was mostly provided in the historic Library of Congress Classification system, comprising the basic metadata and also the subject headings as per the Library of Congress Subject Headings scheme (LCSH); later other systems developed. Additional information such as International Standard Book Number (ISBN) and the Library of Congress Classification Number (LCCN), which provided a unique identification for that work in that system, were also provided along with page.

Publishers and independent bibliographic service-providers began to provide the same services for the library regarding the books in their collection for a fee.

As computers became available, printed and card catalogs were replaced in libraries by computer database software designed for cataloging and made searchable electronically. The programming could be done inhouse or obtained commercially. This naturally led to the development of standards so that bibliographic information could be shared between computers in recognizable, identical formats. Standards of various types developed for most aspects of library classification and cataloging.

Some examples of standards are:

- Resource Description and Access (RDA), a standard for descriptive cataloging;

- MARC (machine-readable cataloging) standards, a set of digital formats for the description of items catalogued by libraries, such as books etc., in computer software.

- International Standard Bibliographic Description, a set of rules for creating a bibliographic description in a standard, human-readable form

After computerization, each item in the catalog collection was stored as a computer record in the database by the software. So, the database comprising the catalog of a library consisted of a set of records in the database, which could be searched by the user on computer terminals for use by the public, using a software known as Online public access catalog or OPAC.

With local networks, and later, the internet providing networked communication, catalogs and bibliographic services went online and began to network.

Now a library could get its bibliographic information about a particular published resource online from a repository, from another library, or the publisher. Standards developed to facilitate this, such as the Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules (AACR), once very popular but now defunct, and now replaced by the RDA.

Notes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ The reasons for cataloging are specified in the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR) (as amended/updated to 2018), which provides a conceptual model from the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA).

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Catalog". Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Springfield, Massachusetts, USA: Merriam-Webster Inc. Archived from the original on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ↑ Cutter, Charles Ammi [at Wikipedia] (1891). Rules for a Dictionary Catalog. Special Report on Public Libraries. Vol. II (3 ed.). Washington DC, USA: US Bureau of Education, Government Printing Office. p. 8. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ↑ Joudrey, Daniel N.; Taylor, Arlene G. (2018). The Organization of Information (4th ed.). Santa Barbara, California, USA: Libraries Unlimited. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-1-4408-6129-1.

- ↑ Joudrey & Taylor (2018), pp 23–26.

- ↑ Joudrey, Daniel N.; Taylor, Arlene G.; Miller, David P. (2015). Introduction to Cataloging and Classification (11th ed.). Santa Barbara, California, USA: Libraries Unlimited. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-59884-856-4.

- ↑ Joudrey & Taylor (2018), pp 25–26.