Circuit Theory/Phasors

Phasors

[edit | edit source]Variables

[edit | edit source]Variables are defined the same way. But there is a difference. Before variables were either "known" or "unknown." Now there is a sort of in between.

At this point the concept of a constant function (a number) and a variable function (varies with time) needs to be reviewed. See this student professor dialogue. Knowns are described in terms of functions, unknowns are computed based upon the knowns and are also functions.

For example:

- voltage varying with time

Here is the symbol for a function. It is assigned a function of the symbols and . Typically time is not ever solved for.

Time remains an unknown. Furthermore all power, voltage and current turn into equations of time. Time is not solved for. Because time is everywhere, it can be eliminated from the equations. Integrals and derivatives turn into algebra and the answers can be purely numeric (before time is added back in).

At the last moment, time is put back into voltage, current and power and the final solution is a function of time.

Most of the math in this course has these steps:

- describe knowns and unknowns in the time domain, describe all equations

- change knowns into phasors, eliminate derivatives and integrals in the equations

- solve numerically or symbolically for unknowns in the phasor domain

- transform unknowns back into the time domain

Passive circuit output is similar to input

[edit | edit source]If the input to a linear circuit is a sinusoid, then the output from the circuit will be a sinusoid. Specifically, if we have a voltage sinusoid as such:

Then the current through the linear circuit will also be a sinusoid, although its magnitude and phase may be different quantities:

Note that both the voltage and the current are sinusoids with the same radial frequency, but different magnitudes, and different phase angles. Passive circuit elements cannot change the frequency of a sinusoid, only the magnitude and the phase. Why then do we need to write in every equation, when it doesnt change? For that matter, why do we need to write out the cos( ) function, if that never changes either? The answers to these questions is that we don't need to write these things every time. Instead, engineers have produced a short-hand way of writing these functions, called "phasors".

Phasor Transform

[edit | edit source]Phasors are a type of "transform." We are transforming the circuit math so that time disappears. Imagine going to a place where time doesn't exist.

We know that every function can be written as a series of sine waves of various frequencies and magnitudes added together. (Look up Fourier transform animation). The entire world can be constructed from sine waves. Because a sine wave repeats, it doesn't matter at what particular time you look at it; all that matters is where you look relative to the beginning of the period. Here, one sine wave is looked at, the repeating nature () is stripped away. What's left is a phasor. Since time is made of circles, and if we consider just one of these circles, we can move to a world where time doesn't exist and circles are "things". Instead of the word "world", use the word "domain" or "plane" as in two dimensions.

Math in the Phasor domain is almost the same as DC circuit analysis. This is handy, because it means that you don't have to solve differential equations every time you want to solve a circuit. What is different is that inductors and capacitors have an impact that needs to be accounted for.

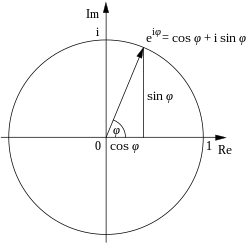

The transform into the Phasor plane or domain and transforming back into time is based upon Euler's equation. It is the reason you studied imaginary numbers in past math class.

Euler's Equation

[edit | edit source]

Euler started at these three series. Obviously there is a relationship:

He did the following:

Set x = π and:

Euler's formula is ubiquitous in mathematics, physics, and engineering. The physicist Richard Feynman called the equation "our jewel" and "one of the most remarkable, almost astounding, formulas in all of mathematics."

A more general version of Euler's equation is:

This equation allows us to view sinusoids as complex exponential functions. A cyclic function represented as a voltage, current or power given in terms of radial frequency and phase angle turns into an arrow having length (magnitude) and angle (phase) in the phasor domain/plane or a point having both a real () and imaginary () coordinate in the complex domain/plane.

Generically, the phasor , (which could be voltage, current or power) can be written:

- (rectangular coordinates)

- (polar coordinates)

We can graph the point (X, Y) on the complex plane and draw an arrow to it showing the relationship between and .

Using this fact, we can get the angle from the origin of the complex plane to out point (X, Y) with the function:

[Angle equation]

And using the pythagorean theorem, we can find the magnitude of C -- the distance from the origin to the point (X, Y) -- as:

[Pythagorean Theorem]

- .

Phasor Symbols

[edit | edit source]Suppose in the time domain:

In the phasor domain, this voltage is expressed like this:

The radial velocity disappears from known functions (not the derivate and integral operations) and reappears in the time expression for the unknowns.

Not a Vector?

[edit | edit source]Some argue that phasors are vectors. Be careful. A phasor diagram is not as rich as vector space or field space either in inspiration, math or concepts. A phasor is just a number .. possibly imaginary number. The phasor diagram is used to "explain" what an imaginary number is. Phasors can be divided, multiplied, added, and subtracted. They are one dimensional things.

The math of phasors is exactly the same as ordinary math, except with imaginary numbers. Vectors demand new mathematical operations such as dot product and cross product. For example can North be divided by East or subtracted from West?

For more details see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phasor_(electronics) or read about this controversy at https://www.quora.com/What-is-difference-b-w-phasor-diagram-and-vector-diagram

- The dot product of vectors finds the shadow of one vector on another.

- The cross product of vectors combines vectors into a third vector perpendicular to both.

These products do apply to phasors, as could be viewed in phasors for AC currents in motor stator and rotor, with the consequence of the creation of a torque, and all of these is expressible exactly by vector products.

Cosine Convention

[edit | edit source]It is important to remember which trigonometric function your phasors are mapping to. Since a phasor only includes information on magnitude and phase angle, it is impossible to know whether a given phasor maps to a sin( ) function, or a cos( ) function instead. By convention, this wikibook and most electronic texts/documentation map to the cosine function.

If you end up with an answer that is sin, convert to cos by subtracting 90 degrees:

If your simulator requires the source to be in sin form, but the starting point is cos, then convert to sin by adding 90 degrees:

Phasor Concepts

[edit | edit source]Inside the phasor domain, concepts appear and are named. Inductors and capacitors can be coupled with their derivative operator transforms and appear as imaginary resistors called "reactance." The combination of resistance and reactance is called "impedance." Impedance can be treated algebraically as a phasor although technically it is not. Power concepts such as real, reactive, apparent and power factor appear in the phasor domain. Numeric math can be done in the phasor domain. Symbols can be manipulated in the phasor domain.

Phasor Math

[edit | edit source]The Appendix

Phasor math turns into the imaginary number math which is reviewed below.

Phasor A can be multiplied by phasor B:

[Phasor Multiplication]

The phase angles add because in the time domain they are exponents of two things multiplied together.

[Phasor Division]

Again the phase angles are treated like exponents ... so they subtract.

The magnitude and angle form of phasors can not be used for addition and subtraction. For this, we need to convert the phasors into rectangular notation:

Here is how to convert from polar form (magnitude and angle) to rectangular form (real and imaginary)

- ,

Once in rectangular form:

- Real parts get add or subtract

- Imaginary parts add or subtract

[Phasor Addition]

Here is how to convert from rectangular form to polar form:

Once in polar phasor form, conversion back into the time domain is easy:

Function transformation Derivation

[edit | edit source]represents either voltage, current or power.

- starting point

- from Euler's Equation

- law of exponents

- .... is a real number so it can be moved inside

- is the definition of a phasor, here it is an expression substituting for

- where

What happens to term? Long Answer. It hangs around until it is time to transform back into the time domain. Because it is an exponent, and all the phasor math is algebra associated with exponents, the final phasor can be multiplied by it. Then the real part of the expression will be the time domain solution.

| time domain | transformation | phasor domain |

|---|---|---|

| proof | ||

| proof | ||

| proof | ||

| proof | ||

| proof | ||

| proof |

In all the cases above, remember that is a constant, a known value in most cases. Thus the phasor is an complex number in most calculations.

There is another transform associated with a derivatives that is discussed in "phasor calculus."

Transforming calculus operators into phasors

[edit | edit source]When sinusoids are represented as phasors, differential equations become algebra. This result follows from the fact that the complex exponential is the eigenfunction of the operation:

That is, only the complex amplitude is changed by the derivative operation. Taking the real part of both sides of the above equation gives the familiar result:

Thus, a time derivative of a sinusoid becomes, when tranformed into the phasor domain, algebra:

- (j is the square root of -1 or an imaginary number)

In a similar way the time integral, when transformed into the phasor domain is:

There is an integration constant that will have to be dealt with when translating back into the time domain. It doesn't disappear.

The above is true of voltage, current, and power.

The question is why does this work? Where is the proof? Lets do this three times: once for a resistor, then inductor, then capacitor. The symbols for the current and voltage going through the terminals are: and

Resistor Terminal Equation

[edit | edit source]- . terminal relationship

- .. substituting example functions

- .. Euler's version of the terminal relationship

- .. law of exponents

- .. do same thing go both sides of equal sign

- .. time domain result

- .. phasor expression

Just put the voltage and current in phasor form and substitute to migrate equation into the phasor domain.

Inductor Terminal Equation

[edit | edit source]- ... terminal relationship

- .. substitution of a generic sinusoidal

- .. taking the derivative

- .. trig

- .. substitution

- from Euler's Equation

- law of exponents

- .... real numbers can be moved inside

- ... substitute in above

- and .. substitute in above

- cancel out the terms on both sides

- .... definition of phasors

- .... equation transformed into phasor domain

Conclusion, put the voltage and current in phasor form, replace with to translate the equation to the phasor domain.

Capacitor Terminal Equation

[edit | edit source]A capacitor is basically the same form, V and I switch sides, C is substituted for L.

- ... terminal relationship

- .. substitution of a generic sinusoidal

- .. taking the derivative

- .. trig

- .. substitution

- from Euler's Equation

- law of exponents

- .... real numbers can be moved inside

- ... substitute in above equation

- and .. substitute in above

- cancel out the terms on both sides

- .... definition of phasors

- .... equation transformed into phasor domain

Conclusion, put the voltage and current in phasor form, replace with to translate the equation to the phasor domain.

In summary, all the terminal relations have terms that cancel:

What is interesting about this path of inquiry/logic/thought is a new concept emerges:

| Device | ||

|---|---|---|

| Resistor | ||

| Capacitor | ||

| Inductor |

The terms that don't cancel out come from the derivative terms in the terminal relations. These derivative terms are associated with the capacitors and inductors themselves, not the sources. Although the derivative is applied to a source, the independent device the derivative originates from (a capacitor or inductor) is left with its feature after the transform! So if we leave the driving forces as ratios on one side of the equal sign, we can consider separately the other side of the equal sign as a function! These functions have a name ... Transfer Functions. When we analyze the voltage/current ratios's in terms of R, L an C, we can sweep through a variety of driving source frequencies, or keep the frequency constant and sweep through a variety of inductor values .. . we can analyze the circuit response!

Note: Transfer Functions are an entire section of this course. They come up in mechanical engineering control system classes also. There are similarities. Driving over a bump is like a surge or spike. Driving over a curb is like turning on a circuit. And when mechanical engineers study vibrations, they deal with sinusoidal driving functions, but they are dealing with a three dimensional object rather than a one dimensional object like we are in this course.

Phasor Domain to Time Domain

[edit | edit source]Getting back into the time domain is just about as simple. After working through the equations in the phasor domain and finding and , the goal is to convert them to and .

The phasor solutions will have the form you should be able now to convert between the two forms of the solution. Then:

If there was an integral involved in the phasor math, then a constant needs to be added onto the time domain solution. The time constant is calculated from the initial conditions. If the solution doesn't involve a differential equation, then time constant is computed immediately. Otherwise the solution is treated as a particular solution and the time constant is computed after the homogeneous solution's magnitude is found. See the phasor examples for more detail.

What is not covered

[edit | edit source]There is another way of thinking about circuits where inductors and capacitors are complex resistances. The idea is:

- impedance = resistance + j * reactance

Or symbolically

Here the derivative is attached to the inductance and capacitance, rather than to the terminal equation as we have done. This spreads the math of solving circuit problems into smaller pieces that is more easily checked, but it makes symbolic solutions more complex and can cause numeric solution errors to accumulate because of intermediate calculations.

The phasor concept is found everywhere. Some day it will be necessary to study this if you get in involved in microwave projects that involve "stubs" or antenna projects that involve a "loading coil" ... the list is huge.

The goal here is to avoid the concepts of conductance, reactance, impedance, susceptance, and admittance ... and avoid the confusion of relating these concepts while trying to compare phasor math with calculus and Laplace transforms.

Phasor Notation

[edit | edit source]- "Polar Notation"

- "Exponential Notation"

- "Rectangular Notation"

- "time domain notation"

These 4 notations are all just different ways of writing the same exact thing.

Phasor symbols

[edit | edit source]When writing on a board or on paper, use hats to denote phasors. Expect variations in books and online:

- (the large bold block-letters we use in this wikibook)

- ("bar" notation, used by Wikipedia)

- (bad ... save for vectors ... vector arrow notation)

- (some text books)

- (some text books)

Differential Equations

[edit | edit source]Phasors Generate the Particular Solution

[edit | edit source]Phasors can replace calculus, they can replace Laplace transforms, they can replace trig. But there is one thing they can not do: initial conditions/integration constants. When doing problems with both phasors and Laplace, or phasors and calculus, the difference in the answers is going to be an integration constant.

Differential equations are solved in this course in three steps:

- finding the particular solution ... particular to the driving function ... particular to the voltage or current source

- finding the homogenous solution ... the solution that is the same no matter what the driving function is ... the solution that explores how an initial energy imbalance in the circuit is balanced

- determining the coefficients, the constants of integration from initial conditions

Phasors Don't Generate Integration Constants

[edit | edit source]The integration constant doesn't appear in phasor solutions. But they will appear in the Laplace and Calculus alternatives to phasor solutions. If the full differential equation is going to be solved, it is absolutely necessary to see where the phasors fail to create a symbol for the unknown integration constant ... that is calculated in the third step.

Phasors are the technique used to find the particular AC solution. Integration constants document the initial DC bias or energy difference in the circuit. Finding these constants requires first finding the homogeneous solution which deals with the fact that capacitors may or may not be charged when a circuit is first turned on. Phasors don't completely replace the steps of Differential Equations. Phasors just replace the first step: finding the particular solution.

Differential Equations Review

[edit | edit source]The goal is to solve Ordinary Differential Equations (ODE) of the first and second order with both phasors, calculus, and Laplace transforms. This way the phasor solution can be compared with content of pre-requiste or co-requiste math courses. The goal is to do these problems with numeric and symbolic tools such as matLab and mupad/mathematica/wolframalpha. If you have already had the differential equations course, this is a quick review.

The most important thing to understand is the nature of a function. Trig, Calculus, and Laplace transforms and phasors are all associated with functions, not algebra. If you don't understand the difference between algebra and a function, maybe this student professor dialogue will help.

We start with equations from terminal definitions, loops and junctions. Each of the symbols in these algebraic equations is a function. We are not transforming the equations. We are transforming the functions in these equations. All sorts of operators appear in these equations including + - * / and . The first table focuses on transforming these operators. The second focuses on transforming the functions themselves.

The real power of the Laplace tranform is that it eliminates the integral and differential operators. Then the functions themselves can be transformed. Then unknowns can be found with just algebra. Then the functions can be transformed back into time domain functions.

Here are some of the Properties and Theorems needed to transform the typical sinusolidal voltages, powers and currents in this class.

Laplace Operator Transforms

[edit | edit source]| Time domain | 's' domain | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time scaling | for figuring out how affects the equation | ||

| Time shifting | u(t) is the unit step function .. for figuring out the phase angle | ||

| Linearity | Can be proved using basic rules of integration. | ||

| Differentiation | f is assumed to be a differentiable function, and its derivative is assumed to be of exponential type. This can then be obtained by integration by parts | ||

| Integration | a constant pops out at the end of this too |

Laplace Function Transform

[edit | edit source]Here are some of the transforms needed in this course:

| Function | Time domain |

Laplace s-domain |

Region of convergence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| exponential decay | Re(s) > −α | Frequency shift of unit step | ||

| exponential approach | Re(s) > 0 | Unit step minus exponential decay | ||

| sine | Re(s) > 0 | |||

| cosine | Re(s) > 0 | |||

| exponentially decaying sine wave |

Re(s) > −α | |||

| exponentially decaying cosine wave |

Re(s) > −α |