Cognition and Instruction/Motivation, Attribution and Beliefs About Learning

Our motivations drive and direct our thought processes and actions. People in developed countries spend about 15,000 hours in school by the time they are 20.[1] It is important to understand the effects this extended school experience has on students' lives and well-being.[2] Research has repeatedly found that as adolescents get older, there is a decrease in their motivation to learn.[3] Researchers are now focusing on ways to sustain students' motivation throughout their school experience. This chapter explains how theories and research on motivation and beliefs about one's self can be applied to teaching and learning. It emphasizes the importance of motivation in learning, and how teachers can motivate students by accommodating and adapting to their needs. Motivation has two aspects that are inter-related.[4] One aspect looks at how much motivation a person has, and the second looks onto what type of motivation it is. [5] There are many theories of motivation, and here we examine three that offer understanding of teaching and learning. The first theory we look at is Self-Determination theory, which looks at two types of motivation and the factors that facilitate them by fulfilling psychological needs. The second theory we examine is Goal-Orientation theory, which looks at the power of goals in relation to the environments they are constructed within. The structure of the environment generally aligns with the type of motivational goal students strive to achieve. The third theory we examine is Expectancy-Value theory, which explains motivation in terms of the expectations individuals have for their performance in particular activities, and what value performance in those activities holds for them.

Self-Determination Theory

[edit | edit source]Self- Determination Theory, first introduced by Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan, primarily looks at two different types of motivation.[6] It states that each type of motivation is built upon a reason or goal that eventually develops into a certain behaviour. [7] The first type of motivation is intrinsic motivation, which is motivation that comes within one’s self for enjoyment and self interest without external pressures or reasons.[8] A student who decides to read a textbook for full pleasure and takes interest in the topic, does so because of intrinsic motivation. [9]On the other hand, extrinsic motivation comes from doing something because it leads to an external outcome. [10]This would be a student who solely reads a textbook because he or she knows there is going to be a test at the end and wants to do well on the test.[11]

Both of these types of motivation topics are extremely important to researchers and educators within the theory, because over the years there have been numerous conclusions, under the view of the Self - Determination Theory, intrinsic motivation facilitated the highest quality of learning because it included using creativity and the existence of psychological needs. [12] With recent research however, there are a few approaches that state that although the highest quality of learning does still involve the core aspects of intrinsic motivation, there are ways to include extrinsic motivators to achieve the same purpose. This will be talked about more in later sections, after defining Intrinsic and Extrinsic motivation more in depth.

Intrinsic Motivation

[edit | edit source]As mentioned above, intrinsic motivation has been concluded to facilitate the highest quality of learning, as it stimulates creativity and satisfies important yet basic psychological needs.[13] According to the Self-Determination Theory there are three personal physiological needs every human tries to fulfill. [14] The first need is Autonomy. Autonomy is defined as being self regulation and self initiating of ones own behaviour and actions. [15] A student who is autonomous would know exactly what is needed to achieve a given task and feels that they have the individual freedom to do so with effort.The second physological need is Competence which is defined as being the ability to attain different outcomes both externally and internally and is successful in doing so using the environment they are surrounded by. [16] For a student this would mean the ability to do well on a difficult exam with the skills that they already have built from previous experiences.[17] Finally, the third physiological need is Relatedness. Relatedness, would be the level of connection one feels from their social environment,[18] where in the case of a student, would be when a student feels that they can relate and connect to what they’re learning as well as with the subjects around them. [19]

Extrinsic Motivation

[edit | edit source]The Self- Determination Theory explains that there are 4 specific types of extrinsic motivation that are different to the degree which they hold autonomy.[20]Starting from the left side of the spectrum, motivation is completely external, and as it moves in the right side direction it moves towards becoming internal.[21] The least autonomous extrinsic motivation on the left spectrum is External regulation. This form of motivation is where behaviours are done to receive an incentive or to avoid a sort of punishment.[22] This would be a student who decides to study for an exam strictly to get a good grade, avoid a punishment by their family members , or not be mocked by external subjects for being incapable.[23] Now moving one to the right side, the next type is Introjected regulation, where motivation would occur solely to fulfill self/internal power and avoid guilt.[24] A student here would change their motive of studying for an exam to elevate their ego and protect their image.[25] Identified regulation comes next, which moves to a more autonomous motivation as its main reason towards acting on something is because it is seen as being valuable and useful for the future.[26] For example studying hard for an exam because you want to do well for your future career would be identified regulation.[27] The final type of extrinsic motivation which is the most autonomous is Integrated regulation, which is closely tied with topics that are being learned combined with one’s self interests.[28] For example, a student might want to study chemistry because it will help them become a doctor which will in turn help others and society. [29]

Promoting and Changing Extrinsic Motivation into Intrinsic Motivation

[edit | edit source]A key reason why it is important for students to improve their intrinsic motivation is that it leads to overall improvements in both psychological health and academic success [30]. Knowing this, many educational psychologists are constantly working towards finding ways to promote the benefits of intrinsic motivation for students in both their school subjects and emotional health [31]. We can look at literacy as a clear example. On average, 73% of American children do not read for enjoyment [32] and we can assume that this rate is high due to students not realizing the benefits of finding intrinsic motivation in literacy. Results show that students who enjoy reading perform higher in comprehension and overall feel more contended; [33] similarities were found with Math. Over the K-12 schooling years for students, academic intrinsic motivation for math shows to have the highest decline [34]. Math has shown to be able to energize students, and those who have intrinsic motivation have higher problem solving skills as well as higher confidence levels when solving complex problems in different aspects of life [35] Students with special needs and special education also proved to show higher rates of confidence[36]. For these students, this positive impact can result in higher hopes for high school completion rates and achievements after finding intrinsic motivation.[37] In regards to emotional behaviour and health, students who were found to have high levels of intrinsic motivation were overall happier with life, and further created a friendlier and positive school environment. [38] Increased motivation also promoted positive social qualities such as being helpful, friendly, and caring. Considering this aspect, results also showed a positive decline in drug use, violence and vandalism. [39]

With understanding the benefits of promoting internal motivation and also acknowledging the degrees of extrinsic motivation, we can now work towards looking at a common concern as to how to change external motivation into internal motivation in the classroom. Let us use an example of a grade 7 class that is spending time on a specific chapter in science. Some of the students feel that the content they are being taught is extremely uninteresting and pointless. The approach teachers should take in a scenario like this is the process of Internalization and Integration, which aims to promote and discover the value of what is being taught.[40] Internalization is the method of analyzing the explicit reasons as to why one chooses to do something with external motivation. Integration is process of taking those external reasons and converting them to come from one’s own self [41]. Here we will see motivation transform from something that was once external (left spectrum) to something that becomes more internal (right spectrum). [42] However, this process can only be achieved or facilitated once students are placed into environments that are allowing them to feel self determined and fulfilled in all three psychological needs of competence, relatedness, and autonomy [43]. The ways that teachers can support this is by allowing students to have a voice and a choice in the academic activities that they engage in. [44], assigning learning activities that are challenging with providing them with the tools and information needed to succeed in the activity.[45], in addition, creating an environment that makes them feel valued, respected, and regarded positively by their teachers and peers. [46]

Cognitive Evaluation Theory and Rewards

[edit | edit source]On a similar note, The Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET) is a sub section of the Self Determination Theory that was presented by Deci and Ryan (1985) [47]. It states that any event that becomes interpersonal or relational, and helps to promote the feeling of both competence and autonomy, will in turn cause intrinsic motivation. [48]The theory however, stresses that they’re both interrelated and that the feelings of competence will not promote intrinsic motivation unless it is aided by the sense of autonomy. [49] Moving this theory into the classroom, when teachers look at assigning a given task or assignment, they should look to see if the guidelines will fulfill the needs of competence and autonomy in the student.[50] For example, this can be seen when a teacher assigns an individual project or presentation for science class. If the teacher allows the students to chose their own topic and pick between giving a project or presentation, it allows them to have control (feeling of autonomy), which in effect allows them pave their own pathway towards feeling successful (feeling of competence). [51]

Under the CET, research has been continuously worked on to find the results of using rewards, feedback, and other external events on intrinsic motivation to see if it further promoted or decreased the feeling of competence and autonomy. [52] The Cognitive Evaluation Theory explains that external events can do either, depending on how one’s self determination or competence is perceived [53]. If an event decreases the way one perceives them, it will decrease intrinsic motivation whereas if it increases the way they perceive them it will increase it.[54] The Cognitive Evaluation Theory also claims that the two aspects of rewards, wether they are either informational or controlling, can answer this question [55] Informational increases intrinsic motivation and controlling decreases it.[56] To determine if a reward is either controlling or informational, it is first important to define the difference between verbal and tangible rewards.[57]

Verbal Rewards are often replaced with the common term “positive feedback ”[58] It has strongly been suggested and assumed that positive feedback will increase intrinsic motivation as it is likely to fulfill a student’s need to feel competence and be informational.[59] However it is important to realize that verbal rewards may have a controlling aspect as well. It can lead to a student doing actions for the sole purpose to gain appraisal and approval. (i.e. teacher or peers)[60]. The CET therefore claims that the rewards must be looked at in the terms of interpersonal context which looks at the social atmosphere that students are surrounded by( i.e. a classroom)[61]

Tangible Rewards are opposite of verbal words and are rewards that are strongly associated with being controlling and contributing to decreasing intrinsic motivation.[62] For them to be controlling, they have to be looked at as rewards that are offered as incentives for students to do things that are out of their regular norm.[63] This could mean that the student would be motivated to do something because they knew what the expected outcome of the reward was going to be. [64]The CET takes this understanding and explains that expected tangible rewards are broken specifically based upon the tasks or circumstances that students are asked to participate in.[65] It outlines that there are three types of reward circumstances.[66]

| Task-Non Contingence | Rewards that are given to students for participating in an activity |

| Task-Contingence | Rewards given to students for completing an activity |

| Performance-Contingence | Rewards given to students for completing an activity, showing success, and performing well |

The use of rewards in the classroom has been a long term debated topic, as both researchers and teachers aim to consider what kinds of rewards are best to give to students and when they are the most appropriate to give as well[67]. A recent meta analysis study was done to test the effects of verbal and tangible rewards in the classroom. The effect of verbal rewards showed exactly what was claimed above.[68] When verbal rewards were informational they increased intrinsic motivation and if they were to be controlling it decreased it.[69] They also found that verbal rewards had a higher significance in increasing intrinsic motivation in adolescents in college than younger students in primary school.[70] Similarly, similar results were found with experiment with tangible rewards as they showed to diminish intrinsic motivation. However, in this situation, the effect on students was higher in younger students than for adolescents in college.[71] In regards to teachers and educators giving rewards, it can be implemented in the classroom but only to be used in an appropriate manner. Verbal Rewards are highly recommended however only when it informational.[72] Although Tangible Rewards show negative results, they too can also be implemented in the classroom, however the best method for implementing them include making the rewards unexpected so that the students are not aware of what will be rewarded to them.[73]

Teachers

[edit | edit source]While working to apply the Self Determination theory in the classroom with students, it is important to analyze the environments that students are exposed to and look at the effects of how the external environment plays when working towards creating an environment that creates intrinsic motivation. Here we will look at the effects of teachers, and the effects that teachers have directly upon students.

Because teachers play a major role in a student’s life , there are many ways teachers can influence students. The first way teachers can achieve this is by simply being intrinsically motivated themselves [74] A study was done to see if intrinsic motivation from teachers could disseminate to students in a high school physical education class. Results positively showed that when working with a intrinsically motivated teacher, higher levels of intrinsic motivation in physical education were achieved than working with a teacher who was extrinsically motivated for external rewards( i.e. being paid) [75] Similar results to promote an intrinsic environment were shown when a study was done to look at how teacher’s support for basic needs effected school bullying levels. The study included looking at 536 students, grades 7-9 in different Hong Kong secondary schools, where students were asked to fill out a questionnaire based on different measures they had felt throughout that semester.[76] Some of the questions included asking students how often they excluded someone, how often they felt they were a bully victim, and how often they felt their teacher showed support in relatedness, autonomy, and competence. Results showed that the lowest amount of bullying took place in schools when teachers had shown high levels of support in relatedness, and students had felt that they had a personal bond and open relationship with their teachers. [77]

Expectancy Value Theory

[edit | edit source]In a school and learning environment, students are always making choices when it comes to what motivates them and how they act on that motivation. These choices often revolve around how much effort to put into different activities; for example one student might not put any effort into their schoolwork, but may try exceptionally hard in sports, while another student puts effort into every class but physical education. Expectancy Value Theory; which was developed by Atkinson and built upon largely by Eccels and Wigfield, tries to explain this concept by stating that performance and choice are most strongly influenced by the specific understanding a person has on what they are capable of in different fields, and on what they find important to them.[78] Culture, emotion, and outside parties such as parents or teachers have also been deemed by researchers such as Richard Pekrun to be influential in adding value to certain activities.[79]

Wigfield and Eccels' Model of Expectancy Value Theory

[edit | edit source]One of the most well received models of the Expectancy Value Theory was initially developed in 1983 by Wigfield and Eccels, with the model still being further developed.[80] What makes Wigfield and Eccel’s model of Expectancy-Value Theory significant is that it easily applicable to teaching and learning as it examines the individual more closely. As a whole, Wigfield and Eccles' model examines ability and expectancy beliefs and personal values as significant to the expectancy-value theory.[81] Expectancies and values are influenced by an individual’s beliefs in their abilities, which tasks they define difficult or simple, goals, and past learning.[82] Expectancies and values are then in turn seen as directly influencing an individual’s choices, performance, effort, and persistence.[83] When discussing the model in the context of schooling, Eccels and Wigfield identify four different values that are present in the classroom.

| Intrinsic Value | Utility Value | Attainment Value | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| The level of enjoyment a specific activity or task gives an individual. [84] | An individual finding a certain task or activity to have a quality of usefulness; whether it is related to a present or future goal, or to please parents or friends.[85] | An individual recognizing the success in a certain activity as important.[86] | How an individual views a certain task or activity in terms of its cons, such as if any other opportunities will be lost in the place of doing this one and the amount of effort it will take to complete.[87] |

These values further tie in with ability beliefs to create the certain expectancies and levels of motivation an individual sets to a certain task. Ability Beliefs are defined as an individual’s insight on how capable they are at certain kinds of tasks.[88] Wigfeild and Eccels state that while ability beliefs are based on present ability, expectancies are based on what they expect of themselves in the future.[89]

Another important aspect of the model to examine in regards to the classroom is how a student’s expectancies and values develop over the years, and when they start to develop. Wigfield and Eccles state that children start recognizing what activities they are good or bad at and what value different activities have from as early as kindergarten or grade one.[90] This includes the various domains found within a school environment, such as math, reading, music, and sports.[91] These insights on what areas they were successful in also changes over the years as students continue learning. For example, ability and expectancy beliefs for reading generally increase from a grade four student to a grade seven or grade ten student,[92] meaning that an individual who does not view themselves as a strong and confident reader may eventually become confident in their reading skills.[93] This is especially significant because it shows that teachers can try to help students develop their values and expectancies in different subjects. However, an individual can also experience a decline in their values and expectancies for different subjects.[94] For example, students tend to value math more in elementary school than they do in high school.[95] Wigfield and Eccel’s model describes that this can be due to two main reasons; first that children become better at self-assessment through criticism and comparison and can therefore highlight weaknesses in their abilities and in what they value.[96] The second explanation is that the school environment changes over the years of elementary and high school by becoming more competitive, which leads to students adjusting their expectancies for achievement.[97]

Raising Value in the Classroom

[edit | edit source]A first question to ask when examining ways to increase student value towards class material is what makes value something worth spending time on? In 2012, a research study by Gregory Liem and Bee Leng Chua was done to examine expectancy and value in the classroom and which were more effective in student raising motivation and performance. The study consisted of a sample of 1664 Indonesian high school students in Civic Education classes in West Java.[98] Selected from a total of six schools, the 1664 students included 812 males and 852 females from the Year 7 to Year 12.[99] In order to assess whether expectancies or values were more influential, Liem and Chua gave the students a set of questionnaires that assessed what the students expected from themselves in their civic education classes, how they valued the class, their future goals, their civic capital, and factors such as gender and school level.[100] Overall, the questionnaires showed that though expectancies were effective, values had a much stronger effect on individual students’ motivation and performance (304). This means that in a teaching setting, it is important to try to make connections to the different values that may be present in students. As discussed earlier, Wigfield and Eccles’ model identifies four different values; utility value, intrinsic value, attainment value, and cost.

1. Strengthening Utility and Attainment Values

In Liem and Chua’s study, it was also found that motivation to learn and interest in material in the civic education class were especially strong if the student’s future and career goals were related to civic education.[101] This means that as the subject material had a direct quality of usefulness to those students, they possessed a higher utility value for the subject material.[102] Furthermore, the direct utility value the students shared with the material also raised a higher attainment value, meaning that it was important for them to do well in that class[103]. Therefore an effective way to get students more motivated to engage with certain material is to teach them why education is important, why the specific lesson is useful to them, and how it connects to the future role they will play in society. Though university students have a better understanding of which courses offer utility value, high school and elementary students may need extra help from teachers to explain why the connection is useful to them. For example, for high school students some ways to engage utility value is to discuss any university programs or future career goals they may be interested in and make explain how that course is relevant to them; such as explaining that a programming class can provide a good knowledge base for any who want to go into Information technology. For activities such as essay writing, this may make a student more eager to learn and motivate them to do well in the class; especially as students are starting to look into universities. Engaging utility value in elementary students may be extra beneficial for the students as an early understanding of why education of certain material is important may increase the students overall desire to learn and engage in schooling. As elementary teachers work more closely with the same group of students in every subject, they have a unique opportunity to appeal to their students as to why certain material is important. One of the best ways to do this is to be selective of what material is chosen to teach and how to teach it while still staying within curriculum, which can also be taken into account for high school students. For example, Jere Brophy of the University of Michigan states there are three significant steps that can be taken to aid in this.[104]

| Step | Significance |

|---|---|

| 1. Curriculum Development | Careful selection of curriculum to make sure everything the students are learning is worth learning while still following school requirements.[105] |

| 2. Scaffolding Application | Apply scaffolding techniques to make sure students are given plenty of opportunities to develop new skills and learn for themselves how to apply what was learned while making sure they are applying their knowledge in beneficial ways.[106] |

| 3. Lesson Framing | Frame Lessons in a way that makes sure to explain the value and application of all material and skills being taught. [107] |

Overall, explanation and understanding is the key to engaging student’s utility and attainment value by having students understand how to apply the skills they are learning and why they should want to succeed in learning them.

2. Engaging Intrinsic Value

As stated earlier, intrinsic value is the level of interest or enjoyment a student finds in lesson material. Intrinsic Value is closely related to the Self-Determination Theory aspect of intrinsic motivation that was described earlier, as whenIan individual finds intrinsic value in a task, it can become intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic value and intrinsic motivation can be very varied depending on the individual as all individuals have their own specific interests. This also means that what an individual finds intrinsic value in cannot be changed with extrinsic factors. Therefore, as teachers cannot change what a student finds interest in, one of the most effective ways for a teacher to raise student intrinsic value is to build and maintain a good relationship with their students. Overall, studies show that an emotionally and academically supportive teacher can lead to higher interest and intrinsic motivation, and therefore higher academic effort. A study conducted by Julia Dietrich a, Anna-Lena Dicke , Barbel Kracke and Peter Noack with math teachers shows how positive and negative relationships with teachers can affect both the individual and the classroom.[108] On an individual level, a supportive teacher led to higher positive associations with intrinsic value, effort, and long-term development in math;[109] while an unsupportive teacher led to a negative association and lower development. On a classroom level, a shared perception between students of a teacher as supportive led to a positive association of class levels of intrinsic value and motivation, with increased skill development over the year.[110] However, if a class deemed a teacher unsupportive, class levels of motivation were lowered.[111] This shows that it is overall beneficial try to provide students with emotional and academic support. However, this is further developed by good relationships with multiple teachers, as it leads to positive comparison.[112] Dietrich et al’s paper describes this Comparative Process as comparing one’s own achievements with their own achievements in other classes or with other students.[113] This process can also occur between experiences with other teachers. For example, if a student finds the teacher of one grade or subject to be less supportive than another teacher, their motivation in the class of the less-supportive teacher may decrease.[114] This shows that while it is important to ensure that a teacher is creating an emotionally and academically supportive environment, it is equally important that all teachers and staff work together to ensure that they are all setting a similar teaching standard for their students.

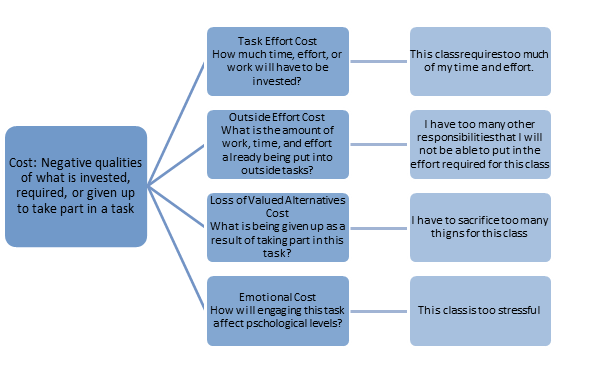

3. Overcoming Cost Of all of the values described in Wigfield and Eccle's model, cost is the most unique as it is influenced by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Though engagement of the other values may limit the amount of negatives a student identifies in a task by increasing its importance, many of the qualities of a task that influence an individual student to make decisions are outside of the teachers control. This increases as students get older and begin to be in charge of more decisions, for example a high school or university student picking their courses. An article by Jessica Flake et al describes how cost can be split into four identifications, Task Effort Cost, Outside Effort Cost, Loss of Valued Alternatives Cost, and Emotional Learning Cost.[115] The chart below is an adaptation of a chart shown in Flake's article that explains how different costs lead to different decisions and behavior.

Though teachers may not be able to limit what cost values a student might be influenced by, learning how these costs affect student's decisions can provide a deeper understanding of why students make specific choices. This can then better prepare a teacher to cater to the needs of individual students and identify specific problems.

Raising Expectancy in the Classroom

[edit | edit source]Though the Wigfield and Eccle’s model of Expectancy-Value theory focuses more strongly on values, expectancy and ability beliefs are still fundamental the theory’s application. As mentioned earlier, building on student values within the classroom is an effective way to also raise expectancy. However, there are still other ways that expectancies can be built upon. Furthermore, as expectancy and ability beliefs are considered to be more domain specific over activity specific,[117] they can be improved in a much more general way than values. For example, one of the most applicable ways to raise expectancy in the classroom is by building on base skills.

The Importance of Reading Programs

Improving students' expectancy and motivation in reading is one of the most effective and easily applied ways to increase an individual’s overall expectancy. As reading is a base skill, a higher expectancy in reading skills can then make a student more confident in their overall learning abilities. A study by Christopher Nkechi showed that the implication of Extensive Reading Programs; a program that requires students to read several books over a span of a few months, were beneficial in increasing motivation through raising self-expectancy in reading.[118] Many researchers have done studies showing that these programs are extremely beneficial for students whose first language is not the language being taught, with many examples using English as the second language. However, Nkechi showed that these Extensive Reading Programs are also extremely beneficial for students who already speak the language being taught, using native English speakers in his study.[119] One of the main aspects of the Extensive Reading Program used in Nkechi’s study was Literary Circles. Literary Circles is a group activity that uses scaffolding strategies by assigning each group of students with a novel to read, and then requiring each student to go through a rotation of assigned roles.[120] These roles not only encourage the students that might otherwise be disengaged or unwilling to read the novel in order to keep up with their group, but require the students to find meaning and message in their readings.[121]

For Nkechi’s study, 96 students were split into groups and rotated through three to four novels.[122] Each student was then asked to fill out a questionnaire about their expectations for the program both before and after completion of the program. Once the students completed their program after several months, the results showed that the program overall raised student expectancies and beliefs in their reading ability.[123] Overall, the study showed that Extensive Reading programs help students become more capable in different aspects of language and how to use their capabilities in different forms of media and activities.[124] These ER programs also help develop vocabulary, which is significant as in order to make sense and meaning of texts an individual needs a 97-98% vocabulary coverage.[125] Though lessons can target and teach certain specific words, these reading programs supply students with general vocabulary and how to recognize it.[126] Extensive Reading programs also supply a student with more exposure to grammatical laws, which can provide deeper examples after the basics have been taught to them.[127] As reading provides a base from which to learn many different subjects, increase in expectancy in reading abilities can also help raise expectancy in other subjects where reading in order to understand subject material is required. Therefore, as a whole these programs are easily implemented in a classroom and are successful in increasing students expectancies in reading and comprehension in all subjects.

Goal Orientation Theory

[edit | edit source]Early conceptualizations of goal orientation theory are derived from James A. Eison's work on dimensions of student's learning and grade orientations.[128] Eison looked at the structure of student's educational and personal differences; he viewed them in relation to learning for genuine acquirement of knowledge, versus performing for attaining high grades.[129] Subsequently, Dweck postulated similar ideas categorizing mastery and performance goal orientation.[130] Dweck's work established goal orientation theory as a two-dimension construct wherein students either approach situations with the motivation to master and acquire new skills, or perform in order to gain approval and do better in comparison to others.[131] People have different reasons for setting goals and as such, each person approaches their goals differently. Goal-orientation theory seeks to explain the underlying implications of motivation in academics.[132] Students are categorized by their mastery goal orientations or performance goal orientations.[133] A mastery goal orientation reflects genuine purpose as people work towards mastering a set of skills in order to accomplish a task.[134] Students with mastery goal orientations pursue goals for their own sake.[135] It is important for teachers to structure lessons that assist students in obtaining a mastery goal orientation. Teachers can accomplish this by relating learning to personal growth and by co-constructing objectives that are relevant to the student's interests.[136] Consequently, by focusing on personal growth in the learning process, teachers can increase intrinsic motivation which activates a mastery goal orientation.[137]

Studies have also found students that adopt mastery goal orientations demonstrate more adaptive self-regulatory behaviors and social attitudes, which contribute to an increased interest in learning.[138] Teachers must be willing to continually adjust their methods and instructions in order to create optimal learning conditions. In doing so, they create an environment that aligns with their student's goal orientations. The instructional approach must avoid tasks that encourage memorization and rehearsal, for example.[139] However, how can teachers ensure their students are learning appropriate information without incorporating tests and exams? Teachers can facilitate in-class discussions, group projects, papers, and presentations in order to gauge the level of understanding and also the amount of content being absorbed by students.[140]

Performance goal orientations highlight how well an individual can demonstrate success in tasks and understanding.[141] Performance-oriented individuals are competitive and focused on personal gain prompted by extrinsic rewards.[142] Furthermore, mastery and performance goals can be divided into subcategories of avoidance.[143] The former, describes students who wish to avoid misunderstanding tasks, lessons, or instructions; the latter, describes students who wish to avoid appearing incompetent during performance.[144] Overall, students with mastery avoidance and performance avoidance goals fear failure.[145] Teachers must avoid creating a class atmosphere that is high risk and high reward. That is, they must place less emphasis on external motivation and achievement in relation to others.[146] The structure of the classroom is contingent on the teacher's representations of goals, values, and beliefs; for example, does the teacher focus on how well students perform in comparison to one another, or how the students improve throughout the year?[147]

Students can have adaptive goal orientations because they engage in multiple goal paths.[148] Studies also identify a combination of learning and performance cues that exist outside the classroom; two prime examples are the ways in which parents and peers influence student motivation.[149] Consequently, teachers need to be aware of how parents and peers contribute to shaping of a mastery goal orientation. [150] In a longitudinal study conducted by Juyeon Song, Mimi Bong, Kyehyoung Lee, and Sung-il Kim, surveys were administered to assess variables in learning and home environments that influenced student's motivation; psychological attitudes students felt towards school were included in the assessment as well.[151] Subsequently, the data was used to measure the degree of perceived support from parents and teachers; they found that certain types of support promoted different types of goal orientations.[152] Parents and teachers that stressed achievement increased test anxiety, compared to parents and teachers who supported students with emotional encouragement.[153] The preceding study supports the notion that teachers need to foster intrinsic motivation in the classroom.[154] They can do so by continuing to nurture student's emotional development so there is no discrepancy between the care and support they receive at home and at school; in this way, teachers are also able to combine the student's home and school lives representing a comfortable space for students to develop their learning.[155] Moreover, offering emotional support shows student's that they are worthy of care and this can reverse adverse effects of achievement pressure.[156]

Another study by Javier Fernandez-Rio, Jose A. Cecchini, and Antonio Mendez-Gimenez tested cooperative intervention programs against traditional teaching programs in order to find out which method generated more intrinsic motivation.[157] The study participants were university students between their early twenties and early forties.[158] The participants were split into either an experimental condition in which they were taught through cooperative reciprocal learning, or they were placed in the control condition wherein traditional unilateral instruction was applied. [159] The cooperative intervention program influenced positive perceptions of competence and enhanced intrinsic motivation.[160] In addition, cooperative learning encouraged students to work with one another and problem solve together.[161] If applied in a classroom setting, cooperative learning supports mastery goal orientations through peer to peer interaction as they learn to work together and not against each other; as they are required to solve problems and work through differences to achieve a common goal.[162]

Both of the studies presented above hold important implications for the classroom. Finding the source of motivation can also assist in guiding future goals, achievement goals, social goals, and personal well-being goals towards a more mastery oriented goal state.[163] Parents and peers are significant influences in a student's motivation and as such, teachers must learn to implement their influence in the class. The studies presented above provide teachers with strategies and techniques to approach their class with. Applying social goals in particular, can create more opportunities for peer to peer involvement and can foster a cooperative class climate as well.[164] Feeling comfortable and connected to peers helps students discover meaning which enhances the development of a mastery goal orientation.[165] The sociocultural framework helps teachers investigate motivation through its use in cross-cultural contexts.[166] It enables teachers to identify aspects of the class climate that sustain mastery; for example, by allocating more time for group work and discussions.[167] Parent, teacher and peer involvement are intertwined; teachers must always keep this in mind so they can understand their students and their intentions for learning. Consequently, teachers can support mastery by guiding future goals, achievement goals, social goals, and personal well-being goals if they involve all aspects of the student's home, school, and social life.[168]

Assessment and intervention are two methods in goal-orientation theory that can help identify and shape the types of goal orientations that will persist in the class.[169] One way teachers can assess whether a mastery or performance goal orientation exists is by applying interventions such as the Likert scale.[170] Questionnaires help teachers get a feel for the class’ impressions and expectations. Surveys also assist teachers in acquiring important information about their student’s beliefs regarding success in the class.[171] Teachers can use this data to reorder their instructional process and better explain a path to meaningful success. Surveys are beneficial because they can vary in specificity and target information.[172] For example, asking students to share their aspirations and motivations can provide insight into student conceptualization of the learning process and therefore, assist teachers in setting classroom objectives that support a mastery goal orientation. In the same way mastery goal orientations can balance performance goal orientation, qualitative methods can complement quantitative methods.[173] In applying a diverse range of methodology such as open and structured observations, talk-aloud protocols, conversation analysis, life history and ethnography, teachers can gain a fuller understanding of the nature and origins of goal orientations.[174]

Goal Structures

[edit | edit source]There are two types of goal structures that align with the mastery and performance goal orientations.[175] The goal structure however, refers to the environment and the ways in which outside conditions can affect student’s motivation, cognitive engagement and achievement.[176] It emphasizes the specific goals to be achieved in the classroom by way of instruction and practice.[177] The teacher must be cautious when organizing the curriculum as the types of tasks delegated and marking process influence goal structure.[178] In addition, the level of freedom students are given to explore and group arrangement, both contribute to forming a particular classroom goal structure.[179]

As noted above there are two types of goal structures known as mastery goal structure and performance goal structure.[180] A mastery goal structure embodies a learner focused environment wherein the standards and policies encourage students to try hard and do their best.[181] Teachers can create a mastery goal structure through clear explanations of the objectives; for instance, by telling students the purpose of performing tasks is to expand their knowledge.[182] Teachers that offer choice in their activities, such as allowing students to pick their own essay or presentation topics, piques interest by targeting subjects students are passionate about. Students are taught to value themselves as well as the learning process in this way as well.[183]

A performance goal structure creates an atmosphere of rivalry and competition.[184] Success comes from obtaining extrinsic rewards and performing competently in various tasks.[185] Teachers can better shape their classrooms by determining which goal structures foster approach and avoidance goals.[186] For example, mastery goal structures foster mastery approach goals.[187] Teachers can administer anonymous surveys and the questions can help indicate whether students acquire more of a mastery or performance goal orientation. In addition, because goal structures usually mirror the environmental conditions, they are observed as impacting the specific goal orientations that students adopt.[188] Applying this to a classroom setting, teachers must remain cognizant of the goals students perceive as being important in the class because they will correspond to their personal goal orientations.[189]

Research has proposed that teachers who placed higher worth on learning and working hard resulted in students viewing their environment as mastery structured; therefore, students were more likely to assume a mastery goal orientation.[190] Teachers can implement classroom contracts at the beginning of the school year to solidify the working conditions. Cultivating mastery goal structure enhances student drive for more challenging work and they are better able to adapt in order to succeed.[191] Students learn to effectively employ learning strategies in the presence of mastery goal structures as well.[192] Self-report measures assist teachers in identifying connections and discrepancies within student’s goal structures and goal orientations; they are able to analyze reported levels of choice, effort and persistence in order to understand a student’s adaptive motivational engagement.[193] Ultimately, mastery goal structures promote mastery goal orientations that encourage intrinsic motivation, cognitive engagement and achievement.[194]

Mastery Goal Orientation and Performance Goal Orientation

[edit | edit source]Goal orientations originate in schemas and can be made purposeful in context.[195] Students perceive cues and prompts from the situation that leads them to adopt either mastery goal orientations or performance goal orientations.[196] Asking student’s questions about their past can trigger positive intrinsic experiences that reactivate their schemas for mastery goals.[197] By asking students to draw upon experiences of happiness and success during their academic careers, teachers place more of an emphasis on mastery goal orientation that can be similarly attained in the class.[198] Questions that require deep reflection also help students continually adapt and challenge their goals to coincide with their mastery goal structures.[199] Students can recognize differential emphases on mastery goal orientation and performance goal orientation.[200] Subsequently, they align their perspectives and behaviors accordingly.[201]

Tasks, authority, recognition, grouping, evaluation and time are all aspects of the class setting that influence goal orientation.[202] The following examples illustrate the implications and relationships to instruction.

Tasks

Teachers must consider what they are asking their students to do when assigning specific tasks.[203] What is the outcome they wish to obtain? If teachers are asking students to listen to a lecture and soon after write a quiz, students will adopt a performance goal orientation.[204] The demand level and structure of such a task places external pressure on students and detracts from a meaningful experience.[205] In order to prevent this from happening, the teacher can engage students through a more flexible task structure.[206] For example, allowing students to participate in an online discussion forum allows them to go at their own pace and use their creativity.[207] Discussion forums are powerful because students can internalize input from their peers in order to create meaning.[208]

Authority

Authority refers to the teacher’s dominancy or openness towards the structure of the class rules and regulations.[209] Strict regulations and rules reflect intolerance for change insinuating students are not active participants in decision-making for their own learning.[210] However, teachers can create contracts with students in order to layout guidelines and responsibilities.[211] Furthermore, instructors can assign a date in the middle of the school year to request feedback and make revisions if necessary.[212] In this way teachers demonstrate their concern for student's wellbeing and personal growth.[213]

Recognition

Recognition addresses the outcomes and actions that must be attended to in order to foster mastery goal structures.[214] Extending effort, taking risks, being creative, sharing ideas and learning from mistakes are all acceptable and functional behaviors to encourage within the classroom.[215] In addition, teachers should express praise in private because publically commending students can foster competition and undermine the abilities of others.[216]

Grouping

Grouping takes different dynamics into consideration.[217] Criteria includes appreciating differences by grouping students with different domains of interests together; in doing so, students are given the opportunities to share, interact and interpret perspectives outside their own.[218] Groups represent the inherently social climate embedded in the class.[219] Mastery is co-constructed as teachers and peers participate in guided meaning making.

Evaluation

Evaluation communicates much about task, teacher and overall course objectives.[220] Therefore the manner in which evaluation is carried out holds vast implications for both instructors and students.[221] Teachers must avoid comparing students based on final outcomes and they can do so by evaluating based on progress, creativity and mastery of skills.[222] Much like recognition, evaluations should also be conducted in private.[223] Teachers can implement weekly progress reports and students can track their personal growth. Allowing students to measure their mastery of skills also allows the teacher to gauge what types of adjustments and provisions could be offered.

Time

Time is a critical factor in establishing a mastery goal structure and mastery goal orientation appropriately.[224] Time restrictions communicate completion over quality. For this reason, teachers should be accommodating by letting students work at their own pace.[225] Teachers must also be open to allocating time according to the level of task difficulty.[226] For example, although some students can complete their work by the end of class, other students may feel anxious from the time pressure and thus, require more time. Moreover, teachers can leave more class time to complete work, but allow students to take the material home as homework if work remains incomplete.[227] Mastery goal orientations maintain a stronger motivation to learn because they nurture personal growth in the learning process while fostering an ongoing desire to improve.[228]

| Tasks | Authority | Recognition | Grouping | Evaluation | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allowing student to choose their own topics for research | Instructor is open to collaborating with students | Identifying creativity and learning from mistakes | Grouping by diversity; pairing students with a variety of learning strategies | Holistic approach reviewing progress and development; encouraging reflection | Allocating an adequate amount of time for learning and structuring knowledge |

Mastery Avoidance and Performance Avoidance

[edit | edit source]Mastery avoidance goals and performance avoidance goals are concerned with the image one reflects.[229] For example, students with a desire to avoid performing poorly and appearing incompetent in comparison to others are concerned with performance avoidance goals; whereas, students concerned with mastery avoidance goals strive to avoid misunderstanding the task or material presented.[230] Performance avoidance goals have been tied to negative outcomes and low achievement.[231] Generally, performance orientations are less adaptive than mastery orientations regardless of the approach or avoidance orientation that results.[232] Moreover, in relation to the self, performance avoidance goals are associated with negative emotions and overall, wellbeing. Subsequently, students characterized by mastery avoidance fear becoming incompetent as a task and strive to evade it at all costs.[233] Akin to performance avoidance goals, findings have revealed that mastery avoidance goals are also linked to maladaptive outcomes including poor implementation of cognitive strategies and procrastination.[234] It is not enough to encourage mastery goal structures and mastery goal orientations in the class; teachers must also understand the roles that avoidance orientations play and their implications for instruction.

Summary of Motivation

[edit | edit source]The purpose of this chapter is to demonstrate how motivation can be increased in the classroom through certain popular theories such as the Self-Determination Theory, the Expectancy Value Theory, and the Goal Orientation Theory. In general, we can see that a good reason to encourage intrinsic motivation is because it leads to increased levels in both psychological health and academic success. Setting the context for learning is an important aspect of the teaching environment because it influences the goals set out for the class. Encouraging intrinsic motivation supports student's genuine purpose and passion to master skills. In the self-determination theory we saw that intrinsic motivation is triggered once students feel fulfilled in three psychological needs which are autonomy, competence, and relatedness. In the expectancy value theory we looked at how a student's performance and choice are influenced by what they expect of themselves as well as what they value. More importantly, we look at how to increase expectancy and value in the classroom in order to raise motivation. In the goal-orientation theory we saw that evaluations hold important implications in the classroom by allowing time for reflection on the development of mastery. Through this chapter we hope that present and future educators can use these applications as a way to increase motivation in the class.

Suggested Reading

[edit | edit source]Motivational Beliefs, Values, and Goals

Eccles, Jacquelynne, & Wigfield, Allan. (2002). Motivational Beliefs, Values, and Goals. Annual review of Psychology, 53. 109-132.

Expectancy-Value Theory of Achievement Motivation

Wigfield, Allan, & Eccles, Jacquelynne. (2000). Expectancy-Value Theory of Achievement Motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 68-81.

The Contributions and Prospects of Goal Orientation Theory

Kaplan, A., & Maehr, M. L. (2007). The Contributions and Prospects of Goal Orientation Theory. Educational Psychology Review, 19(2), 141-184.

Advancing Achievement Goal Theory: Using Goal Structures and Goal Orientations to Predict Students' Motivation, Cognition, and Achievement

Wolters, C. A. (2004). Advancing Achievement Goal Theory: Using Goal Structures and Goal Orientations to Predict Students’ Motivation, Cognition, and Achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(2), 236-250.

Intrinsic Versus Extrinsic Goal Contents in Self-Determination Theory: Another Look at the Quality of Academic Motivation.

Vansteenkiste, M., Lens, W., & Deci, E. L. (2006). Intrinsic versus extrinsic goal contents in self-determination theory: Another look at the quality of academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 41(1), 19-31. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep4101_4

Glossary

[edit | edit source]Ability Beliefs: Ability Beliefs are the beliefs an individual has on how capable they are at certain kinds of tasks.

Attainment Value: Attainment Value is the value an individual finds in a certain task or activity from recognizing that success in that activity is important to them.

Autonomy: Autonomy is the ability to be self regulated and self initiating of ones' own behaviour and actions.

Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET): The Cognitive Evaluation Theory is a sub section of the Self Determination Theory that was presented by Deci and Ryan (1985). It states that any event that becomes interpersonal or relational, and helps to promote the feeling of both competence and autonomy, will in turn cause intrinsic motivation.

Competence: Competence is the ability to attain different outcomes both externally and internally by using the environment they are surrounded by.

Cost: Cost is the negative qualities that an individual attaches to certain activities or tasks. Examples of this include missed opportunities from selection of that task over others, and the amount of effort the activity will take.

Curriculum Development: Curriculum Development is the careful selection of curriculum and content to ensure that everything students are being asked to learn is worth learning.

Expectancy Value Theory: Expectancy Value Theory is a theory first developed by Atkinson that defines performance and choice as being influenced by the certain values and self-expectations an individual has for certain activities.

Extensive Reading Programs: Extensive Reading Programs are programs that require students to read several books over a span of a few months, and are beneficial in increasing motivation through raising self-expectancy in reading.

Goal-Orientation Theory: Goal-orientation theory explains the reasons and choices individuals make that maintain motivation. The theory states that individuals have two major goal orientations; mastery goal orientations and performance goal orientations.

Goal Structure: Goal structures embody the learning environment. Goal structures are shaped by the language used by an instructor, the assigned tasks, and the incentives employed to facilitate learning.

Intrinsic Value: Intrinsic Value is the level of enjoyment and interest an individual finds in a specific activity or task.

Lesson Framing Lesson Framing is the structuring of lessons in a way that makes sure to explain the value and application of all material and skills being taught.

Literary Circles: Literary Circles is a method used in Extensive Reading Programs that uses scaffolding strategies by splitting students into groups, assigning each group of students with a novel to read, and then requiring each student to go through a rotation of assigned roles. Each group typically reads more than one novel together.

Mastery Avoidance: Mastery avoidance is the desire to avoid misunderstanding tasks and information.

Mastery Goal Orientation: Mastery goal orientation focuses on intrinsic growth and development. Individuals who acquire a mastery goal orientation are genuinely motivated and value the learning process.

Mastery Goal Structure: Mastery goal structures influence mastery goal orientations. Mastery goal structures foster learner focused environments based on intrinsic motivation.

Performance Avoidance: Performance avoidance is the desire to avoid performing poorly and appearing incompetent in comparison to others.

Performance Goal Orientation: Performance goal orientation focuses on extrinsic rewards such as grades, prizes, and praise. Individuals who acquire a performance goal orientation only wish to appear competent in relation to others.

Performance Goal Structure: Performance goal structures influence performance goal orientations. Performance goal structures foster competitive environments based on extrinsic reward.

Relatedness: Relatedness is the level of connection one feels from their social environment.

Scaffolding Application: Scaffolding Application is the application of scaffolding techniques to ensure that students are given opportunities to develop new skills and learn for themselves how to apply the skills they have learned.

The Self- Determination Theory: Self- Determination Theory , first introduced by Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan, and is a sub section of motivation that primarily looks at two different types of motivation. It states that each type of motivation is built upon a reason or goal that eventually develops into a certain behaviour.

Utility Value: Utility value an individual finds in a task or activity related to the degree to which an individual finds a certain task or subject to be useful to any short term or long term goals.

Wigfield and Eccles' Model of Expectancy Value Theory: Wigfield and Eccles' model of the Expectancy-Value theory states that expectancies and values are influenced by an individual’s beliefs in their abilities, which tasks they define difficult or simple, goals, and past learning.

This chapter examines the role of attribution and emotion in teaching and learning. We will be discussing attribution theory, the four stages of the attributional process, methods for helping students cope with emotions, attributional retraining and implications for instruction. Any event that occurs in our everyday lives can be interpreted in a variety of ways, depending on what we identify as the cause of the event. Our causal attributions have consequences for our emotions and behaviours which, in turn, affect learning and achievement. Attribution theory classifies emotions and links them to types of attributions. As educators, we can take our student's affective and behavioural responses into consideration to ensure that they know how to cope with their emotions. In addition to our student's emotions, we should also be aware of our own feelings and how they are expressed towards our students. Attribution theory can be applied in the classroom environment by providing attributional retraining to students identify and change their maladaptive attributional responses.

Attribution Theory

[edit | edit source]We often come across events in our lives that can be interpreted in several different ways. The explanation that we come up with to describe the cause of an event is referred to as an attribution. [235] The way an event is attributed causes us to react with a variety of responses. To study how people interpret events taking place in their lives, researchers use attribution theory. Attribution theory gives insight into why people have different responses to the same outcomes.

To illustrate the theory, imagine that two students take a math test and both end up receiving 60 percent. One student is very disappointed with herself and vows to create a study group in order to earn a better grade for the next test. She also goes to her teacher for extra help. The second student is angry when she sees her test grade and goes to her friends to see how they did. When she discovers that a few of her friends also performed poorly, she attributes her failure to a poorly written test. Although the outcomes of the situation are the same for both students, the way they interpret and respond to the experience is very different. Later on in the chapter, we will take a more in-depth look into how different attributions affect the way we cope with failure. We can gain a deeper understanding of why people make specific attributions, what the most common attributions are, what types of affective responses are elicited and the effect that attributional judgments have on our behaviour by studying the attributional process.

Importance of Attributions as a Predictor of How People Cope with Failure

[edit | edit source]The significance of attributions is highlighted in the study "Importance of Attributions as a Predictor of How People Cope with Failure" done by Follette and Jacobson. [236] The purpose of this study is to replicate and expand on the research of Metalsky et al. (1982), which focuses on the reformulated learned helplessness model (RHL). Measuring general attributional style, specific attributions for examination performance and the prediction of motivational deficits, this study aims to emphasize the significance of attributions to help predict how people cope with failure in a classroom setting. We will be referring back to this study throughout the attribution theory section of this chapter.

One hundred and ten subjects from an upper division, undergraduate psychology course participated in the study. There were 28 men and 82 women. The participants were asked to complete the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, 1967), the Expanded Attributional Style Questionnaire (EASQ; Peterson & Seligman, 1984) and an additional questionnaire including the following questions: “What grade do you expect to get on the next exam?”, “What grade would make you happy?” and “What grade would make you unhappy?” The questionnaire period was labelled as Time 1. Following this, the students completed an adjective checklist (Zuckerman & Lubin, 1965). It was used to assess three types of moods, including anxiety, hostility and depression. This assessment took place 12 days after Time 1 and 2 days before the actual examination. Seven days after Time 2, students completed the last step in the study, designated as Time 3. Their actual examination grades were returned along with the final package of questionnaires. The package included the checklist for assessing mood, two forms soliciting the students’ attributions for their examination performance, a questionnaire asking about their future plans to help prepare the next examination and a request asking them to report their actual grade. The study concluded with a final debriefing of the participants.

The materials used in this study include the Expanded Attributional Style Questionnaire, Mood Affect Adjective Check List, Exam attributional measures and the Planned Behaviours Questionnaire.

The EASQ distributed to the students measures attributional style for negative hypothetical events. The participants were asked to imagine themselves in each situation and write down a possible cause for the event. There was an equal distribution of both affiliative and achievement situations. Examples include, “You have been looking for a job unsuccessfully for some time” and “You meet a friend who acts hostilely to you”. The participants were then asked to rate the cause of each situation using a 7-point Likert scale. The first three dimensions are internal-external (ranging from completely due to others to completely due to my own efforts), stable-unstable (ranging from will never be present again to will always be present) and global-specific (ranging from influences only this situation to influences all situations). Peterson and Seligman added a fourth dimension, control-no control that asked subjects of the study to rate the degree of control that they believed they would have in each event. The calculated score of this study was only based on the first three scales.

The Mood Affect Adjective Check List Today Form (MAACL; Zuckerman & Lubin, 1965) is comprised of 132 items that are used to detect the subjects’ moods based on three dimensions: depression, anxiety and hostility. In addition to measuring depressed mood at one point in time, the MAACL was also used to assess the change in participants’ mood over a short period of time in this study.

Students’ attributions for their grade on the examination were measured in two ways. Firstly, participants were given an indirect probe, which requested that they list their thoughts and feelings about their performance on the exam. There were several boxes on the form, in each of which subjects were asked to list one thought or feeling. The participants were told that they did not have to fill in all the boxes. This method of examining attributions allowed for more spontaneous thinking and was potentially less reactive compared to some of the instruments traditionally used in attribution research. For the second part of the exam attributional measures, the subjects were then asked to rate the cause of their examination performance with the Likert ratings that were used in the EASQ. The cause of the event was rated on the four dimensions: internal-external, stable-unstable, global-specific, and control-no control dimensions. For each of the student’s responses to the indirect probe, two trained undergraduate coders rated whether an attributional thought was developed. Statements that explained possible causes for a participant’s examination performance were coded as attributions. Examples include: “The test was deceptively easy,” “My score reflected the fact that I had two midterms and an assignment due on the same day,” and “I should study harder.”

The Planned Behaviours Questionnaire (PBQ) was designed by the authors specifically to use in this study. Participants were asked to give an estimate of the number of hours they spent studying for the examination they had just completed. Following this, they were then asked to estimate the number of hours they intended to spend studying in preparation for the next exam. Finally, the questionnaire was concluded with this final question: “Do you intend to do anything different from what you did to prepare for this exam when studying for any future exams in this class? “Please list anything new that you plan to do in preparation for the next exam” The new behaviours listed were counted to see how many participants chose the same method in order to study for the next exam in this class.

The regression analyses of the study were comprised of several factors. The preexamination MAACL depression score was a covariate that was entered in into the equation first. Next, the degree of stress was added into the equation. This variable was the difference between the score that would make the participant happy and the actual examination grade that they received, based on the traditional 0.0-4.0 grading scale. The greater the discrepancy between the two grades, the higher the stress score the participant received. The third component that was entered into the equation was the composite attributional style variable. This variable was calculated by taking the sum of internal-external, stable-unstable and global specific dimensions for hypothetical situations on the EASQ. The final and most important component entered into the equation was the product vector of the interaction between attributional style and stress level to test the diathesis-stress model of depressed mood. Table 1 and Table 2 can be found with the study here. [237]

Additional results of the study showed that under high stress conditions, the tendency to make internal, stable and global attributions resulted in greater depression. For students that received a grade within close proximity to the grade that would make them happy, their attributional styles did not have an effect on their mood. Because no correlation was found between the attributions made for hypothetical events and real life stressors, a similar correlation was calculated for the study. The results showed that only the attributions made based on real life situations were useful in explaining variability in mood.

The Four Stages of the Attributional Process

[edit | edit source]The attributional process is comprised of four main components. One is outcome evaluation, the process of determining whether or not an outcome is favoured. The second is attributional responses, the explanations we attribute to causing the result. The third is affective responses, the emotional responses that follow the interpretation of the outcome and the last is behavioural responses, the course of action that we take to respond to the experience. One main aspect of the attributional process to keep in mind is that specific events do not trigger behavioural reactions directly. These responses only take place after the outcome is cognitively interpreted. All four of these stages can be observed in the previously mentioned study.

Outcome Evaluation

[edit | edit source]Outcome evaluation refers to the process by which we determine whether an outcome is desired or not. These evaluations are based on several criteria. One is the individual’s prior history to encountering similar outcomes. An example of this could be a student that consistently excels in math class, but receives an average test score on his final exam. He could interpret this outcome as undesirable. Another aspect of outcome evaluation is performance feedback. A student that falls below a pre-established standard may view his performance as unfavourable. Evaluations of various outcomes are also dependent on the characteristics of the person, such as the need for success, the perceived value of the task and the expectations of others. The final standard for outcome evaluation is based on cues from others. When a student regularly exceeds expectations, submitting an average assignment may be deemed unfavourable by their teacher, while his classmates can turn in work of the same quality and receive praise from the teacher. [238] These four components make up the criteria for outcome evaluation. Using our previous example from above, we can say that both of the students deemed their math test outcome unfavourable, leading them to make their own attributional responses.

Attributional Responses

[edit | edit source]The second step of the attributional process is explaining the outcome with a particular cause. Follette and Jacobson's study shows examples of various attributional styles using the hypothetical situations of the EASQ and the exam attributional measures. Examples from the study show attributions based on internal and external sources, stable and unstable conditions and global-specific influences. We can also consider our previous example. Upon seeing her mediocre test mark, the first student attributes her poor performance to her lack of preparedness. The second student responds by putting the blame on the quality of the test written by her teacher. The difference in the two students’ responses can be better explained by the locus of control.

Locus of Control

[edit | edit source]Attributional responses are interpreted in three dimensions. The first dimension is the locus of control, which defines the outcome as being caused by an internal or external source. [239] One example of an internal cause is mood. The performance of a student can be affected by mood, which is controlled by the student himself. An external variable affecting performance may be the student’s parents. This is an example of an external variable because the student’s parents have an effect on his performance but the student himself has no control over the situation. In reference to the study, both internal and external attributions were made about the students' examination scores. One student attributes their score to having two midterms and an assignment due on the same day. This student attributes their failure to an external source rather than considering a lack of preparedness. An example of an internal cause from the study is a student that attributes their below average test score to the minimal effort that they put into studying for the exam.

Stability

[edit | edit source]The second dimension of attributional responses is stability. It is defined by how consistent the factor is when encouraging success. Various aspects of performance such as ability, effort and luck can be ranked in terms of how stable each condition is. The dimension of stability is frequently connected to a person’s expectancy of success. If a student attributes their success to a typically stable variable such as ability, it is highly plausible that past success will occur again. On the other hand, if a student attributes their success to a more random cause such as luck, there is a much smaller chance of seeing repeated success. Participants of the study were asked to rate the cause of an event ranging from never being present again to always being the reason for this situation to occur.

Controllability

[edit | edit source]Controllability is the third and final dimension of the attributional responses. It describes the degree to which the individual can influence the cause behind the outcome. Several factors such as effort and strategy use can be highly controlled whereas ability and interest are considered less controlled. Uncontrollable causes, such as the difficulty of a task and luck do not contribute to an individual’s repeated success. There is a strong connection between the controllability dimension and the amount of effort and persistence an individual puts into completing a task. Outcomes deemed more uncontrollable tend to encourage anxiety and avoidance strategies while more controlled variables can lead to increased effort and persistence.that appear from the matrix can elicit numerous affective and behavioural responses.

Affective Responses