Fundamentals of Transportation/Timetabling and Scheduling

In the previous unit on service planning, the strategic decisions of network and route design, stop layout, and frequency determination were described. In this unit, the tactical decisions associated with creating a service schedule (timetabling), creating a schedule for vehicles to operate the service (vehicle scheduling), and creating work shifts for operators (crew scheduling) are presented. A practical guidebook and learning tool has been published recently.[1]

The motivation for good solutions to these tactical decisions is to minimize the net operating costs to the agency. Once the timetable is determined, the number of vehicles required to be in revenue service can also be identified. When the vehicle schedule is determined, the total mileage and hours for the vehicle fleet are defined. Finally, when the crew schedule is determined, the total cost of labor (operators) is defined. Since these factors are the primary determinants of operating costs, finding efficient solutions has a direct effect on the bottom line.

In many cases, these tactical activities are assisted by software tools that can generate high quality solutions in a short period of time, often with direct interaction with the planner. As a result, the interested student may wish to consult other sources to identify and to investigate the specific software tools that might be available, such as those described in a recent publication.[2]

Timetabling

[edit | edit source]The general idea behind timetabling is to create a schedule for service. As inputs, one would consider the frequency of service for the given route (see previous unit) and the expected travel times between stops on the route. The latter could be determined either by historical experience or through estimates based on traffic conditions, vehicle acceleration and deceleration characteristics, expected dwell times, etc.

Let h be the selected headway for a route, perhaps for a specific time period of the day.

Let tij be the time between stop i and stop j along the route, where i and j are adjacent stops. The travel times between stops, tij, can vary by time of day, particularly as they may be affected by traffic conditions. They may also reflect any slack time built into the schedule between stops, to allow for possible variability in travel times.

Finally, let t0 be the dispatch time (departure time) of the first vehicle from a terminal.

Then, the timetable can be created simply using the following structure, with n stops on the route and k+1 vehicles to dispatch:

| Stop 1 (Terminal) | Stop 2 | Stop 3 | Stop 4 | ... | Stop n (Terminal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ... | |||||

| ... | |||||

| ... | |||||

| ... | |||||

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| ... |

The primary decision variable here is the initial dispatch time, t0. Different operating conditions might lead to a number of possible choices for t0:

- “Clockface” values. Passengers may remember the schedule more clearly if the dispatch times fall at easily recognized times on the clock. For example, with 15-minute headways, there may be value to passengers in dispatching a vehicle on the :00, :15, :30, and :45 of each hour.

- Coordination for improved vehicle scheduling. When a vehicle finishes its trip at a terminal, it will often be turned around to continue onto the next trip in the opposite direction on the route. In this case, there is a need for sufficient layover time at the terminal. If the vehicle finishes a trip at time t, then completes the layover after an additional time tL, then the vehicle may start its return trip after t + tL. Choosing the dispatch time to occur at or slightly after t + tL allows for higher vehicle utilization.

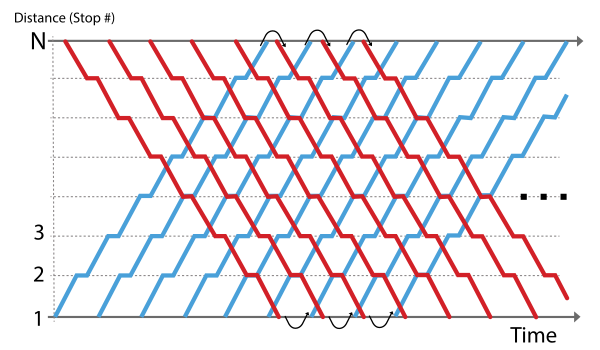

- One way of visualizing such a system uses a so-called “string diagram,” shown in this figure. The blue lines indicate the trajectory of a vehicle from the terminal at stop 1 to the terminal at stop n, with short dwell times at each stop. Vehicles arriving at stop n then can return along the route in the opposite direction (the red lines), after a layover (indicated by the black arrows). These diagrams can be useful in visualizing vehicle movements and crosses along the route.

- Coordination of passenger transfers. In some cases, it may be desirable to choose the dispatch time so that passengers may connect to other routes in the network without unduly long waiting times for the transfer route. To do this consistently across the timetable, the two (or more) routes that connect for the transfer must have the same headway h. If this is the case, then the initial dispatch time t0 can be chosen so that the vehicle’s arrival time at the transfer point matches that of the vehicle on the connecting route.

- Reduction of vehicle requirements. The timetable will dictate how many vehicles are in operation at any time of the day. In some cases, minor adjustments in the dispatch times, coupled with changes in layovers and/or dead-heads of vehicles between terminals can lead to a reduction in the number of vehicles needed for service.

Vehicle scheduling

[edit | edit source]Vehicle scheduling, also called “blocking”, involves assigning vehicles to cover the trips associated with the timetable. A vehicle “block” is the schedule of travel of a vehicle for a given day, including: (1) a pull-out from the depot, (2) a sequence of trips from the timetable, (3) any dead-head trips, and (4) a pull-in back to the depot (recall the vehicle cycle from the unit on vehicle operations).

Generally, once the timetable is created, the time and mileage that vehicles spend in revenue service (i.e., completing the trips in the timetable) is fixed. So, the usual goal in vehicle scheduling is to minimize the time and/or distance that vehicles spend outside of revenue service: e.g., pull-ins, pull-outs, dead-heads, and layovers. These all represent time or mileage that are “unproductive”, and hence should be minimized.

Constraints on this process include the following:

- Each trip in the timetable must be made by a vehicle.

- A vehicle cannot be assigned more than one trip at any point in time.

- If a vehicle must be re-positioned for a trip, the associated travel time and distance from its current position to the new position must be observed.

To solve for the vehicle schedule, one might consider a simple “first-in-first-out” rule. In this case, a vehicle stays on the same route throughout the whole period, and is always assigned to the next trip after a layover. The string diagram above gives just such an arrangement.

As a simple example, suppose we have a route that runs from terminal A to terminal B and then back to terminal A. Travel time from A to B and from B to A, including running and dwell time, is 30 minutes, and a minimum 5 minute layover is needed at each terminal. Headways are 15 minutes.

Below is a timetable for this situation, for trips between 6:00 am and after 9:00 am. The left-hand side of the timetable shows vehicle trips from A to B, while the right-hand side shows vehicle trips from B to A.

The colors correspond to different vehicles used on the route. The gray color corresponds to the first vehicle of the day, leaving A at 6:00 am and continuing with the trip from B at 6:40, the trip from A at 7:15, etc. A total of five vehicles are required to cover all the trips in this timetable.

In addition to the trips from the timetable, the vehicle block also includes a pull-out and pull-in, so that the final block for the first vehicle (gray) could look like the following.

For networks with longer policy headways (e.g., 30- or 60-minute headways), longer layovers at terminals may be necessary if vehicles serve the same route throughout the block. As a result, other options can be considered, particularly in terms of shifting vehicles from one route to another. The timetable may allow vehicles to shift from one route to another, in order to reduce layover time and/or to avoid pull-outs or pull-ins. Specific activities in the block can include:

- Interlining: the process of switching a vehicle from one route to another at a terminal, when the routes share that common terminal.

- Deadheading: the process of switching a vehicle from one route to another, also requiring a re-location of the vehicle (traveling empty) to another terminal.

These methods can be quite effective under different timetabling conditions.

Crew scheduling

[edit | edit source]Crew scheduling (also called “run-cutting” in the transit industry) is the task of determining work shifts (so-called “duties” or “runs”) for operators. Generally, the primary interest in crew scheduling is to minimize the total cost of labor that meets the service requirements.

A significant fraction, typically 60-70%, of the total operating costs at a transit agency involves the cost of operators, including wages, benefits, and other premiums. With this in mind, small reductions in the number of operators, or in the total work hours, can result in more substantive reductions in the total operating cost. For this reason, the task of scheduling crew to vehicles is one area where many large transit agencies can achieve some efficiencies and potential cost savings.

Crew scheduling is complicated because operators often cannot simply be assigned to a vehicle for the entire vehicle block. First, the shift would often be much longer than a typical 8-hour work period; and, second, the operator may not get sufficient break time during vehicle layovers (e.g., for lunch). Instead, the duties have to consider more practical concerns of the operators.

In this regard, transit agencies have rules that dictate the kind of work shifts the operators may perform. In most cases in the US, the types of work shifts are governed by collective bargaining agreements (union work rules) that specify work conditions for transit operators. Possible examples of work rules could include restrictions like the following:

- A duty should start and end at the same terminal

- Crew needs at least 2 breaks during the day: a normal (15-min) break and a (30-min) lunch break

- A break is required after no more than 3 hours of work

- Each crew must have at least 8 hours off before resuming duties on the next day

- Only 20% of duties can be longer than 9 hours

- Only 25% of duties can be split into intervals with an unpaid break (e.g. a duty that only covers the AM and PM peak periods)

- Only 30% of duties can be covered by part-time operators

The general approach to creating a crew schedule begins by cutting each vehicle block into “pieces of work.” Each piece of work is a subset of trips in the block, forming the elemental unit of work (driving) for the operator. Then, according to the constraints from the work rules, these pieces of work are assembled into feasible duties. The hope is to assemble a full set of duties such that all pieces of work are covered and that the total cost is minimal. The cost of a duty can depend on both the traditional hourly rate of pay for the operator for hours worked. If the operator has a straight shift (no unpaid break), they are paid a certain amount, usually at a given hourly rate. Other costs can include:

- A minimum guarantee of hours of pay, if the guarantee exceeds the number of hours worked (e.g., 8 hours of pay, even if the operator works only 7 hours);

- Premiums for overtime (e.g., time in the duty over 8 hours);

- Premiums for spread time. Spread is the total time between the start and end of a duty. If this exceeds a certain maximum (e.g., 9 hours), the operator is entitled to extra pay;

- Premiums for swing. Swing occurs when the duty starts and ends at different locations (terminals, depots);

- Premiums for split duties, where the duty has an unpaid break. This can occur when an operator works only the AM and PM peak periods, without working in the mid-day;

These rules on pay suggest that the crew schedule should contain as many straight duties as possible. Small pieces of work that remain after generating these straight duties can be allocated to part-time operators (if they are available), to avoid other premiums, or covered using split duties with associated split and/or spread penalties.

A second problem in crew scheduling is rostering, in which duties are assembled into a group of duties (the “roster”) for each operator, by week. For example, one roster could include the same 8-hour duty for 5 weekdays. However, many possible combinations of duties could be considered, especially if weekend or evening service is provided. Once the rosters are created, operators choose from among these duty rosters.

Glossary

[edit | edit source]- Block: the sequence of trips made by a vehicle in the course of one day of operations, including both revenue and non-revenue trips.

- Duty (or, Run): a work shift for an operator for one day.

- Guarantee: the minimum pay hours for an operator, regardless of the number of hours worked.

- Piece of work: an operator work assignment extracted from a vehicle block.

- Relief: the change of operators during a vehicle block.

- Roster (also, rostering): the set of duties for a single operator in a week.

- Split: a duty covering at least two intervals of time with an unpaid break.

- Spread: the time between when an operator reports for duty and when they end their duty.

- Straight: a duty covering a single interval of time.

- Swing: a duty in which the operator begins and ends at different locations.

- Tripper: a short work assignment (e.g., 2–4 hours); generally much shorter than a typical straight.

Related books

[edit | edit source]Avishai Ceder (2007). Public Transit Planning and Operation: Theory, Modeling, and Practice. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Transportation Research Board (2003). Transit Capacity and Quality of Service Manual, Transit Cooperative Research Program, Report 100, 2nd Edition. [3]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Transportation Research Board (2009a). Controlling System Costs: Basic and Advanced Scheduling Manuals and Contemporary Issues in Transit Scheduling, Transit Cooperative Research Program, Report 135. [1]

- ↑ Transportation Research Board (2009b). Controlling System Costs: Basic and Advanced Scheduling Manuals and Contemporary Issues in Transit Scheduling, Appendix, Transit Cooperative Research Program, Report 135 Appendix. [2]