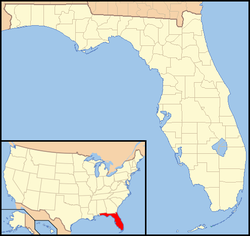

History of Florida/Native American and Colonial “Florida," 1497-1821

Native American and Colonial “Florida,” 1497-1821

[edit | edit source]Introduction

[edit | edit source]

The written records of Florida begin in 1513, with the Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de Leon. The mass of land that he explored on the American continent would come to be named La Florida, in honour of Pascua Florida (Feast of Flowers), which is the name given to Spain’s Easter time celebration. By this time the Spanish had established Spanish hegemony in New Spain and much of the Caribbean. The Spanish soon considered Florida a vital asset in protecting the shipping routes they used to send bullion and other supplies back to Europe, especially since privateering was rampant at this time. With the French in Louisiana, Spanish colonization of Florida held the threat of cutting off their supplies routes to France. To the British, which had interests in the Caribbean and along the east coast, eventual colonization down the coast made conflict all but assured. Thus, Florida would become a focus for British, French, and Spanish colonization. This left many of the native tribes in Florida in a precarious position as they had to deal with the three imperial powers trying to establish dominance, each as likely to prosecute them for any multitude of reasons, but all resulting in exploitation. By the end of the 17th century most of the native tribes would be largely wiped out or nearly exterminated from disease and European aggression.

Pre-Seminole Indigenous Peoples of Florida (1497-1760)

[edit | edit source]The Calusa

[edit | edit source]The Calusa were an indigenous people of Southern Florida located in the southern regions of Florida, and are notable for being highly civilized compared to other tribes. Calusa societies were highly stratified, consisting of a sophisticated class hierarchy; from leader, elite, military class, ecclesiastic, to the common villager. This class based social system had benefits for upper classes comparable to similar class in Europe at the time. For example; leaders and elites had access to food otherwise restricted from lower classes and were exempt from physical labour. The Calusa also had a thoroughly developed complex spiritual belief system that clashed with ideals of colonial powers and missionaries. These cultural differences, specifically between the Spanish and the Calusa, ultimately manifested themselves in the form of Calusa resistance to Spanish Christianization and Hispanicization attempts. Regardless of aggressive actions, such as the Spanish missions in Calusa territory, this resistance was carried out in a largely peaceful way. However this peace would not last and after intensifying negative relations and acts of violence on behalf of the Spanish the peace between the two populations ended. After 1569 there would be no further significant contact between the two. The 18th century marked nearly two centuries of colonial expansion into Florida on behalf of the Spanish, French and later the British that brought diseases and colonial conflict to the region. The Calusa also faced slave raids by Creek Indians led by the British colonies in 1711. This combination of factors had effects not solely contained to the Calusa and meant that by the early 1700s Florida was essentially depleted of an Indigenous presence and the Calusa had become an extinct indigenous people.

The Timucua

[edit | edit source]

The Timucua were an indigenous people native to the Florida Peninsula that occupied the northern central regions from the eastern Atlantic coast to the most easterly areas of the Florida Panhandle in the west.The Timucua population consisted of politically divided chiefdoms only truly unified by language and their subsistence strategies via hunting. Like the Calusa, the Timucua territory also had a Spanish mission that was ultimately abandoned in 1706. However, unlike The Calusa, The Timucua had primary colonial relations with the French that were for the most part were largely peaceful and successful trade networks. The French employed a strategy of “allurement” meant to be more appealing than the sexual violence, rape and slavery that had become customary of the Spanish further south in the Caribbean. Ultimately, the French hoped to convert The Timucua to Protestantism, similar to the Catholicization the Spanish attempted with the Calusa. The Timucua refused, but in the end succumbed to the same fate as their southern neighbours. Colonial slavery raids, warfare, acculturation and relocation by colonial powers and later arriving Creeks pushed The Timucua out of Florida and eventually to extinction.

The Apalachee

[edit | edit source]

The Apalachee were an indigenous population residing in the Eastern regions of the Florida Panhandle bordering the western edge of Timucua territory. One of the three major tribes of the Pre-Seminole era (Apalachee, Timucua, Calusa) the Apalachee were the most “settled” of the three, having well defined boundaries, a material culture surrounding ceramics, cultivation of maize, and social norms surrounding the protection of women and children. Like their southeastern neighbours; the Timucua and Calusa, the Apalachee also housed a major Spanish mission within their territory at Pensacola, as well as the Spanish mission San Luis established in 1663 in the easterly regions of the Apalachee Province of the Florida Panhandle. The Apalachee's regionally specific allegiances and interactions with colonial powers had varying cultural implications resulting in three distinct Apalachee groups; French in Mobile, British in northern Creek territories, and Spanish in Tallahassee. The Apalachee were also the most successful of the three major indigenous tribes regarding sustained, successful economic relationships with the colonial powers; maintaining extensive relations with the French, Spanish, and British. However, like the Calusa these peaceful economic relations would not last due to increasingly restrictive trade regulations and increased Apalachee draft labour by the Spanish, as well as indigenous fear of the British's economic strength. Like the other indigenous people of Florida, raids from Creek Territories led to the relocation and eviction of the Apalachee to St. Augustine and Mobile in 1704. However, throughout the colonial Pre-Seminole era, the Apalachee more than any other indigenous tribe made the colonial economic system work in their favor.

Origins of the Seminole People (1760)

[edit | edit source]The Seminole Tribe of Florida as they are known in their contemporary context were not an indigenous people to the area that is now the state of Florida. Rather the Indians that came to be commonly known to Europeans and identify themselves as the Seminoles were a migrated or fragmented population of Creek Indians from Lower and Upper Creek territory in Georgia and Alabama. After the decimation of the indigenous populations of Florida through disease brought via colonization as well as conflict with European forces and European sponsored indian raids into vast expanses of territory remained largely uninhabited. This represented an amble opportunity for southern expansion into current day Florida by Lower and Upper Creek Indians. These Creeks were drawn into Florida not only due to the ample abundance of land, but also by prospects of trade with Spanish colonies in Latin America by way of The Gulf of Mexico as well as increasing pressures from British and later American southern expansion. As progressively increasing numbers of Creeks expanded into Florida and became separated from the Creek heartland along the Chattahoochee River in Georgia and this satellite population subsequently began to develop their own distinct culture that varied from that of traditional Creek Indians and thus these people became known as Seminoles.

European Interactions in Florida (1497-1821)

[edit | edit source]The Spanish in Florida

[edit | edit source]

There are two periods of Spanish rule in Florida. The first begins after Ponche de Leon first makes landfall in 1513 and continues until 1763 when the Spanish cede Florida to the British. The second is from 1783-1821, where the Spanish would reacquire Florida from the British, only to give it up 40 years later to the United States. Much of Spanish colonization and exploration, while sanctified and supported by the King, was a purely private matter. Much of the expenses for this process was paid out of pocket by the individual. Such an individual was called an Adelantado, and in exchange for funding his missions he was given great judicial and governmental powers over the lands that he took. This paved the way for the mass exploitation of the land, and the natives, for the sake of profit. The man who sought to bring this system to Florida was Pedro Menéndez de Avilés. After eliminating the threat that French colonization held within Florida at the battle for Fort Carolina, word of the massacre that occurred would spread to many of the native tribes. To their eyes, their only options were to submit to the Spanish or to die. The reputation Pedro established from the massacre inspired many tribes to submit. This submission meant accepting catholic missions and openly converting to the faith. Lordship over the Indians was a combination of suppression and gift giving; seeking to maintain alliances with the natives where possible, and crushing any rebellions when they arose. Spain’s power in Florida would not begin to be questioned after this until the 1700’s, and would even temporarily lose control of Florida from 1763 – 1783.

The French in Florida

[edit | edit source]

French settlement of Florida began in 1562, by a group of Huguenots (French Protestants). They would establish the colony of Mobile in the western most region of the Florida Panhandle in close proximity to the Spanish settlement of Pensacola. While the Huguenots would be expelled from Florida in a few short years, one of the gravest concerns to Spanish aspirations was that the French would manage to root themselves in Florida by establishing connections with the indigenous populations. They had already begun this process, but were soon defeated by the Spanish. The tribes that did ally with the French, by the time Pedro Menendez conquered Fort Carolina, would finally submit to the Spanish. The importance of the French colonization efforts in Florida, however, comes from the images created by Jacques le Moyne de Morgues, which are the earliest known visual representations of Florida and its indigenous people. While these images provide some knowledge about Native culture, specifically of the Timucua, they demonstrate greater insight into the aspirations of the French and their efforts to colonize Florida, and generally the perspective of the other European states.

The British in Florida

[edit | edit source]Florida was ceded to the British in 1763 after the Treaty of Paris at the end of the Seven Years’ War. While British rule in Florida would only last until 1783, a mere twenty years before it was given back to Spain, they still tried to do much. Florida under their rule was divided into an east and a west. Similar to the Spanish system, the British during their occupation gave constant gifts to the Indians in an attempt to keep the peace. While the cost of this was high, it was seen to be much less than the cost of war. Of the natives that the British were courting, the most important were the Creek, later commonly known in Florida as Seminoles. In the 17th Century some Upper and Lower Creek populations in fact allied with the British colonies to the north. These loose colonial indigenous alliances had a profound impact on the indigenous populations further south in Florida. British colonialists "employed" most typically Lower Creek Indians to raid indigenous settlements throughout Florida in hopes of weakening rival colonial interests of the French and Spanish in the region by destroying their network of allegiances with the indigenous populations. Eventually these raids coupled with foreign diseases brought by European colonists resulted in a vastly diminished indigenous population in Florida as many either died or were pushed out of the territory due to these raids. These Creek Indians eventually migrated south into Florida due to intensified British colonial expansion into Northern Georgia and vast uninhabited lands to the south in Florida due to the devastation of indigenous tribes. Here these Creeks became disconnected from the heartland of the Chattahoochee River in Georgia and developed a distinct culture that led to their branding as the Seminoles by European colonials.

The War of 1812

[edit | edit source]In 1794, the Thermidorian Revolt expanded across France as a consequential result of leader Maximilien Robespierre’s reign of terror. Robespierre suffered his execution at the hand of Thermidorian rebels as they permanently acted to end the systematic state oppression they for so long endured. Napoleon Bonaparte became the new successor of France, and he hastily began to lead the nation into an 11 year period of continuous war. In 1806, Napoleon implemented a new policy called the Continental System. The goal of this system was to act as a blockade in protecting French manufacturers across all European markets. Correspondingly, the British reacted to this new implementation by cutting off all French commerce from Atlantic markets. In their perspective, anyone who continued to conduct trade with France would from then on, be considered an enemy of Britain. The neutrality of America in the Napoleonic wars would not last for long, as their ships were soon ransacked, and both their goods and men, were taken into British custody for their continual efforts to trade with France. Finally on June 18th 1812, American president James Madison declared war on Britain. Simultaneously, as war was waging overseas, American officials were expanding their territories by tricking Indians into signing treaties that handed away millions of acres of land to the United States. Conclusively, this act would lead to the cooperation of both Britain and Spain with the American Indians as a united force in stopping the United States expansion.

Natives and the War

[edit | edit source]On October 3, 1783, The American Revolutionary War ended with the Treaty of Paris which ceded the lands of Florida over to Spanish control. In 1811, the Americans permanently demanded that the Creeks allow a north-south road to pass through their lands to connect white settlements on the Tennessee River with Fort Stoddert. This was the situation that brought forth the Shawnee chief Tecumseh, into action by uniting Indian tribes through the common goal of protecting their lands against American expansion. Both Tecumseh and his brother, the Prophet, realized what few other Indians ever saw: only if all tribes made common cause could they hope to contain the United States as it exploded out of its borders. Tecumseh’s efforts aroused the Creek and Seminole Indians to join together in war against the United States. At this time, Indian forces were limited to fewer technological advances and supplies than their opponent, and they thus began seeking more powerful allies to join their cause.

1812 and 1813 were critical times in the Gulf Coast area and in Florida for both Spain and Britain. The United States had begun to infringe upon, and disrupt Spanish owned territory. To secure his country’s possessions from further aggression, the Spanish governor Sebastian Kindelon incited the Seminoles and the Negros against the American interlopers in 1812. Simultaneously, Britain had gained powerful Indian allies through their mutual desire of halting U.S expansion, and were willing to provide arms, troops, and training to the Indian and negro forces. Both Spain and Britain began cooperative measures in the hopes of successfully stopping the United States. Over the course of 1814 and into 1815, Colonel Edward Nicolls of the Royal Marine, and George Woodbine, a white trader from the slave and Indian populations of the Southeastern borderlands, worked together in raising minority forces against the United States. Nicolls and Woodbine erected a fort on the Apalachicola River in West Florida and between August and November of 1814, they occupied the capital of Spanish West Florida, Pensacola. Britain utilized the efforts of blacks and Indians, in it’s war planning, for they aspired to exploit southern feats, thereby distracting the southern war effort and inspiring local, able-bodied recruits to join the effort.

After a series of small-scale battles that shifted in success between both sides, the war had finally reached its endpoint. American general Andrew Jackson offered an “ultimatum” to the Spanish governor, for him to expel the Indians and blacks from Spanish territory and to stop Britain’s use of Pensacola as their base. Jackson’s offer was declined, and shortly after on November 6th, he arrived at Pensacola with his army in tow. Upon their arrival, American troops were faced with almost no resistance from the Spanish residents of the town.

The British had taken refuge at Fort Barrancas, located at the mouth of the harbour. As the situation became hopeless, they decided to board the British fleet anchored in the bay, blow up for Barrancas, and retreat to the fort on the Apalachicola river. In the ensuing chaos, British forces, their Indian allies, nearly the entire slave population of Pensacola, and over two hundred Spanish troops evacuated the town. America had conquered the Gulf of Mexico as their own, and with it came the destruction of Indian relations with Britain and Spain.

Britain and the War

[edit | edit source]In 1783 the British Empire lost their territory in Florida to the Spanish. Through this conflict, the British and Spanish rivalry allowed for the United States to be relieved of either of the empires full aggression. However, by 1812, the United States was a far larger threat to Spanish Florida than Britain. The chaos in Europe caused by the Napoleonic wars made it possible for multiple intrusions into Spanish Florida by the United States. The Spanish, as a means to reinforce their loose hold on the Florida territory, supported the Seminole Indians so they would serve as a barrier between them and the United States. As such the Spanish gifted weapons, munitions and supplies to the Seminoles to maintain their strength as well as a peace with the United States.

The war with Britain in 1812 led to unusual tactics by the British to rouse opposition inside Florida. For instance, in Pensacola one British Naval Officer saw the military potential of bringing slaves to the side of the British war effort. Pursuing the tensions he perceived inside the slave society of the U.S. he formed a troop of soldiers of over 200 former slaves fighting with the British. Though the success of the troop was limited, the willingness to fight against slavery alongside the British can be observed as a precursor to the further escalating tensions of slavery during the Civil War.

Florida and the War

[edit | edit source]The history of Florida during the War of 1812 necessarily involves conflicts with native tribes and the Spanish. The area of what is today Florida consisted of Spanish controlled Florida West and East. The conflicts in these regions were characterized by American attempts to forcibly control them. This was not direct warfare with the Spanish, instead it took the form of conflict with Spanish backed Native tribes and a combination of British and Creek forces. As such, native tribes were central allies to all conflicts in Florida. The Seminole, Creek and slaves were seen as an important alliances by both the Spanish and the British, though for different reasons. The Spanish feared that the U.S. was going to annex Florida. Therefore the Spanish strayed from their usual policy of keeping the Seminole as a potential defensive force to increasing their amount of military aid to construct heavily defensible forts. The British during the war saw the same groups as a means to divert attention away from Upper Canada: the focal point of U.S. aggression in the War of 1812. The Seminole and Creek desired to stop the white settlement they regarded as most harmful to their people. They saw the British and Spanish as allies against the United States, so they accepted their aid.

Florida in this period contained precursors of the fast, broad and violent expansion of the territory of the United States across the American continent, which often happened outside federal government jurisdiction. Between 1811 and 1814 bands of settlers, soldiers and militias attempted to invade East Florida in the hopes of expelling the Seminoles and Spanish there. The eventual ceding of Florida to the United States by Spain in 1819 was done in the light of this aggression and a knowledge inside the United States that Congress may declare war on Spain. The prevailing political rhetoric of the era was that the precarious territory of New Orleans and Florida would fall into British control, and the War of 1812 was in part justified by this proposed danger to the new nation. Indeed, all territory controlled by the British in North America was seen as a potential threat, so in this manner Florida is not particularly unique: it was subject to the same kind of policies as other territory like Canada and the North American west.

The Outcome of the War

[edit | edit source]There were contrasting assessments of the war made by the federal government. Some praised the divine providence of the American people in their victory, others more rationally weighed the noticeable victories and failures of the war. A particularly espoused victory was the abandonment of the British naval campaign against the United States which included damaging blockades- which were especially prominent in Florida. The views on the purpose of the war varied greatly. Many argued that it was entirely a war of conquest, done for mere power and territory. This is reflected in the personal records of American soldiers, who rarely recorded their reasons for fighting as beyond a sense of duty or for the money. The outcome of the War of 1812 for the Red Stick Creek was an expulsion from their homeland. Following a defeat at Horseshoe Bend in 1814, Andrew Jackson forced their capitulation with the Treaty of Fort Jackson on August 9th. The treaty ceded 35 million acres of land in modern Georgia and Alabama from the Creek natives and placed it into the control of the United States, and forced the Creek to flee below the border to Florida where they would join the Seminole tribes. The Creek and Seminole tribes would never fully accept the treaty and simply viewed the coming American settlers as intruders on their land. The support of the Spanish was continued after the end of the war in 1815 in order to maintain Spanish control, but was largely done outside Spanish officials knowledge and therefore often lacked adequate resources. The end of the War of 1812 also served to further establish an “American line”- a frontier boundary within Florida between the coalition of native tribes and the United States. In this manner, the Seminole maintained a semi-autonomous state under the Spanish, but it didn't last for long. Under the pretext of Seminole aggression towards the "invaders" of their land, American settlers, militias and soldiers would fight continual skirmishes along the frontier. This frontier territory set the stage for treaties, wars, the ceding of Florida by Spain and the eventual deportation of the Seminole.

The First Seminole War

[edit | edit source]Origins of the War

[edit | edit source]

The War of 1812 had concluded with unrest in the United States. During the war the British had built a fort on the Apalachicola River. In 1816 it was primarily garrisoned by roughly 350 former slaves, thus granting it the nickname of the "Negro Fort". Many southern plantation owners, including Andrew Jackson, considered these former slaves to be renegades and a menace to society, they were afraid that the ex-slaves were going to ruin the innocence of “white woman-hood and the security of the plantation south”. Later that year, in an attempt to bring order to the region, the United States built Fort Scott just north of the Spanish border. Jackson presented the Spanish commander at Pensacola with an ultimatum, either Spain would dismantle the fort or the United States would have to eliminate the fort in self-defense. In actuality, Spain did not have the manpower to perform the task, so it fell to the Americans. The plan for destroying the Fort involved sending gunboat-accompanied supply boats to Fort Scott, which was further in-land on the Apalachicola. This was done in the hopes of provoking the Fort into attacking the boats, giving the United States reason to attack the Fort. The plan worked, and on July 27, 1816 a red-hot cannonball fired from an American gunboat struck the major powder magazine and obliterated the fort. Thus the Negro power on the Apalachicola had broken, and the Seminoles grew weaker. In retaliation for the destruction of the Negro fort, Hitchi chief Neamathla ambushed a US army boat close to Fort Scott, killing thirty-four US soldiers. This infuriated the US, and after Neamathla sent a warning to Colonel David Twiggs: "not to cross or cut a stick of timber on the east side of the Flint." Twiggs led an army of 250 men to capture the Hitchiti chief, resulting in a firefight that killed five Seminoles. However, when Neamathla escaped, Twiggs burned down Neamathla's town, marking the beginning of the First Seminole War. Neamathla's actions set the precedent for guerrilla conflicts along the border, and led to increased border skirmishes during the summer of 1817.

The War and Imperial Relations

[edit | edit source]

The First Seminole War was a violent conflict in Western Florida from 1817-1819, encompassing conflicts between The United States and the Seminole Nation. The Seminoles were formed from Native American tribes that had migrated down from the north and banded together. Some of this migrating due to conflicts such as the War of 1812. Additionally, escaped African American slaves found a home among the Seminoles. Together they raided white American settlements across the border into Georgia and Alabama, killing inhabitants and stealing their property out of Revenge for the Treaty of Fort Jackson. When complete, these native raiders would simply flee back across the border into Florida, away from the Jurisdiction of the Americans. Spain could not control these borders, which forced the United States to take action. Andrew Jackson, commander of the southern military district, led the controversial advance into Florida, devastating the opposition. In the future this order would be controversial; members of congress would later claim that the invasion was unconstitutional, as the legislature and executive branches of the US were not consulted. The conflicts raised tensions between the United States with Great Britain and Spain.

On December 26, 1817 secretary of war, John C. Calhoun, ordered Jackson to enter Florida: "with full power to conduct the war as he may think best", knowing that if given the chance, Jackson would take Florida from Spain. Jackson left in haste soon after his arrival at Fort Scott on March 9, 1818 with an army of 3,300 primarily Tennesean and Georgian militia. On April 1st he moved in on the largest Seminole town of Miccosukee alongside William McIntosh; a half creek who had grown vengeful due to large property losses at the hands of the Red Sticks. There was a rift in the creek confederation, and many creeks stood by the United States. McIntosh lead an army of Creek Indians who would support Jackson in his attack, and together they took Miccosukee with little resistance. There were no signs of withdrawal, and Spanish town of St. Marks was taken five days later. Here the Scottish, Seminole sympathizer; Alexander Arbuthnot, was captured and would eventually bring controversy upon Jackson's campaign.

Jackson’s next target was Seminole chief Bowleg’s Town of Suwanee on the Suwanee River. Here McIntosh's army encountered the main Seminole force and a firefight ensued resulting in the Seminole forces being routed. The army continued at full pace trying to prevent the Seminole inhabitants of Suwanee from crossing the river. However word quickly spread and Suwanee began to evacuate in order to escape the onslaught. Later on in the day they attacked and quickly forced the remaining Seminoles to retreat. Jackson ordered the town to be destroyed, and in the process they captured Robert Ambrister, another Englishman who provided the Seminoles with weapons, and other supplies. Jackson, upon capturing a second British agent in Florida, confirmed his own suspicions of British involvement in the Native aggression towards the U.S. Jackson ordered Ambrister and Arbuthnot to be executed due to the allegations of aiding the Seminoles against the US. These executions would lead to an increased potential for conflict with Great Britain.

After the rout at Suwanee, Jackson quickly learned that 500 hostile Indians had gathered near Pensacola, the main Spanish settlement in West Florida. Jackson marched his army 240 miles to Pensacola which he occupied on May 24th without resistance. There was now only one Spanish center on the peninsula however the assigned task was now complete. The Seminole fighting force had broken west of the Suwanee River and was forced to disperse. Some forces fled to the Alachua area, however many withdrew to Tampa Bay and the lakes of North Central Florida. The Floridian Peninsula was now firmly under the control of the United States.

After the War

[edit | edit source]Although the United States coveted Florida, the executions of Arbuthnot and Ambrister had enraged Great Britain, and they didn’t want to risk Great Britain aligning with Spain in a possible war. Therefore the United States returned St. Marks and Pensacola to Spain despite Jackson's protest. However, recognizing that it had only taken Andrew Jackson eight weeks to conquer Florida, Spain realized that they could hope to maintain control of the Peninsula. They ceded the Florida to the US on February 22, 1819, in a treaty that would be finalized after two years time, and its conqueror; Andrew Jackson, would become its first governor. The First Seminole War had opened a period of population growth and economic gain for the United States. They would continue to prosper and expand for years to come.

Further Reading

[edit | edit source]Granberry, Julian. The Calusa Linguistic and Cultural Origins and Relationships. (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2011): Johnson, Patrick Lee “Apalachee Identity on the Gulf Coast Frontier.” Native South 6 (2013).

Martel, Heathere. “Timucua in deer clothing: friendship, resistance, and Protestant identity in sixteenth-century Florida.” Atlantic Studies 10 (2013).

Stojanowski, Christopher. “Unhappy trails: forensic examination of ancient remains sheds new light on the emergence of Florida's Seminole Indians.” Nature History 114, No. 6 (2005).

Widmer, Randolph J. “The Rise, Fall, and Transformation of Native American Cultures in the Southeastern United States.” Reviews in Anthropology 39, no. 2 (2010).