History of Greece/Introduction

Introduction

Ancient Greece is undoubtedly one of the most important civilizations in history. The Hellenes, the term used by the Greeks to describe themselves, laid the foundations for democracy, philosophy, theater, and the sciences. In architecture the Ionic, Doric and Corinthian orders were perfected and their aesthetic function utilized during all periods up to the modern state. In the plastic arts Greek sculptors shook off the influence of Egyptian statuary with its stylized perspective seeking instead to explore proportion in relation to an aesthetic ideal of perfect form. Above the entrance to the Delphi oracle were inscribed the words "Know Thyself" as an ominous portent to those seeking answers at the sanctuary of Apollo. Critical introspection, of which the Delphic epigram is only one example among many, freed the Greeks from the restraints of censure. The arts and sciences flourished and the great poets and philosophers of Ancient Greece laid bare the human condition in a psychological drama that still resonates today. The Greeks adopting the Phoenician alphabet created a script that would form the basis for the development of other European writing systems. An achievement which is acknowledged today by the English word "alphabet" - a compound of alpha and beta which are the first two letters of the Greek alphabet. For the next three thousand years the written word would be the only method of recording human thought as expressed in language and in three thousand years time people will marvel at the ingenuity of Thomas Edison who devised a machine to record sound. A Golden Age is not defined as a product of linear continuity, though this is the path of progress, but by those individuals or societies who enrich mankind universally. Our debt to the Ancient Greeks is only now being repaid in kind for we truly live in a Golden Age of comparable universal achievements.

Overview

The location and topography of a land is important to understanding the environmental factors that shape a civilization. It allows historians and archaeologists to assign a permanent physical condition under which human development can be traced from the distant past to the present day. A people's response to these conditions is not only interpretative but also flexible allowing them to shape and to be shaped by their environment. The fluidity of this response presents a mosaic of meanings that scholars seek to uncover to explain the origins and development of a civilization. That the Ancient Greeks believed the gods resided on Mount Olympus, the highest peak in Greece, is a reminder of how the physical landscape can determine the cultural foci of a people. Zeus who ruled from Mount Olympus gave to his brothers, Poseidon and Hades, the sea and underworld. To the Greeks this trinity encompassed their religious world with a host of minor deities whose abodes either marked a landscape feature or whose existence gave an aetiological response to natural phenomena. The anthropomorphic nature and transformation of the Olympian deities allowed the Greeks to rationalize their interaction with the natural world of flora and fauna.

The four Greek elements of fire, water, earth and air also belonged to the Gods. It was Poseidon who shook the earth and Zeus who would strike dead with lightning those who did not hold to an oath sworn in his name. To the Greeks these beliefs defined their behaviour and to swear by Zeus held the same gravitas as swearing to truthful testimony on the Bible. The multitude of Greeks myths are not to be dismissed as the archaic practices of a primitive people. The Greeks sought to personify their beliefs within the parameters of their environment assigning characteristics in accord with their knowledge. That the Greeks understood this meant that they expanded their investigation into the elements in a scientific way and separate from the divine though never with a view to displacing the Gods. This tenuous detachment is why the Greeks are still held in high regard as the first to take a tentative step towards a greater understanding of the observable elements.

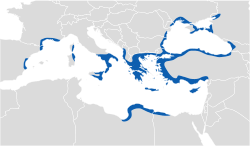

The west coast of Greece faces the Mediterranean and the east coast the Aegean. The west coast of Greece is more favourably placed for trade with Italy and Spain. The east coast of Greece offers access to the coast of Asia Minor as well as the Balkans and the Black Sea. At the southern tip of Greece is the Corinthian isthmus which acts as a land bridge to the Peloponnese peninsula. The north of Greece fans out to the borders of Albania, Macedonia and Bulgaria. Mainland Greece is divided north to south by the Pindus mountain range of which Mount Olympus is the highest peak. The Aegean islands were colonized by Greek settlers in prehistoric times and their importance is reflected in Greek mythology notably as the birthplace of major Greek deities. The two largest islands in the Aegean are Euboea and Crete.

The Spartans claimed Dorian ancestry and in this assertion we may find the clues to the destruction of Mycenaean hegemony and the seeds to future conflict. Archaeologists have long been puzzled by the paucity of Dorian archaeology yet their existence as a tribe is irrefutable based on linguistics. Sparta, a much admired and feared military aristocracy, whose dominance of its tribal neighbours points to a singular purpose also leaves to history less archaeological evidence. The Spartans were renowned for their austerity, severeness and laconic speech and though luxury was no stranger to their tables their myopic militarism does suggest that they were truly the descendants of the original Dorian invaders.

As modern archaeology progresses the dates of human activity are pushed further back highlighting the errors in the assumptions of the twentieth century historian. The Dorian invasion that was believed to have caused the collapse of Mycenae is now being examined as new interpretations of the archaeological evidence points to continuous human activity. The two world wars of the twentieth century act as a caveat against interpreting archaeological evidence of widespread destruction as a prelude or conclusion to permanent displacement. Modern conflict teaches us that despite the destructive forces we unleash upon ourselves the one assurance we have is that as long as people seek to live together society cannot be destroyed.

Primary Sources

The Ancient Greeks have left a wide-ranging body of literature that has profoundly affected the development of Western culture. The Gods and Heroes of Ancient Greece have inspired generations of artists and writers in their muse. Our primary text sources for Greek Mythology are Hesiod, Homer and the anonymous Orphic poets. The Ancient Greeks used poetry as a medium to record their religion and history. For modern readers poetry is strongly associated with the Romantic movement and the expression in language of word-painting. A comparison of the modern romantic poem "Daffodils" by Wordsworth with the Pythian poem written by Pindar for a chariot race victory by Hieron of Syracuse highlights the differences. When approaching the study of Ancient Greek primary text sources the modern conception of poetry as an outlet for the emotional expressions of a poet should be tempered with an understanding of the historical context. The poetry of Ancient Greece developed from oral history and religious practices and though the poetry of Sappho of Lesbos displays the same personal form as Wordsworth the writings of Homer and Hesiod should be understood within the context of declaiming historical and religious practices in poetic form.

An Introduction to Works and Days by Hesiod

The manual Works and Days by Hesiod is a very short agricultural treatise and is a useful introduction to the primary sources of Ancient Greece. It starts with an invocation to the Muses whom Hesiod states in his other work Theogony commanded him to write when they appeared before him as he was shepherding on Mount Helicon. The poem Works and Days is addressed to his brother Perses with whom he has recently shared an inheritance. The first part of Works and Days asks Perses to heed the moral lessons blessed to the Gods and those immoral actions divisive to Man. Hesiod states that his brother has manipulated the division of their father's estate by bribing the Lords whose judgement was final in the matter. Hesiod starts by relating the origins of evil using the medium of Ancient Greek religion. The modern definition of mythology must be discarded when immersing yourself in Hesiod. To the Ancient Greeks their deities carried the same force in matters of spirituality in accordance with our modern concept of religion and therefore the connection is always human. Hesiod will show Perses that the evils that plague mankind are in part of their own making. The events of Prometheus stealing fire to give to humans after Zeus had hidden it from them is used by Hesiod to introduce the concept of human folly. After discovering the theft by Prometheus the angry response of Zeus is to ask Hephaestus, the Blacksmith God, to fashion from clay the first woman, Pandora. Zeus commands the Gods to each give a gift to the humans which will be placed in a jar. Pandora is sent to Epimetheus, the brother of Prometheus, who despite the warnings by Prometheus to not accept gifts from the Gods takes Pandora into his house. Pandora opens the jar of gifts and releases the plague of evils though Hope is stopped from escaping by Zeus. The relationship between predestiny and free-will are bound by our behaviour and Hesiod is clearly stating this to the errant Perses. This is reinforced by Hesiod who relates the history of the five generations of Manː

- The Golden Race of Men

- The Silver Race of Men

- The Ash (Spear) Race of Men

- The Hero Race of Men

- The Iron Race of Men

Hesiod recounts the common Ancient Greek belief in spirits who themselves were once humans. The Golden Race were the most loved by the Gods who blessed them with no evils and a life of ease. Upon their death, which was like falling asleep, they became good spirits who travailed the earth for the benefit of mortals. The Silver Race were created by the Gods and their demise would come during the reign of Zeus who had usurped his father, Cronos, ruler of the Golden Race. The Silver Race were destroyed by Zeus for not worshiping the Gods and upon their destruction became the good spirits who travailed the underworld of Hades. The Ash Race were permanently at war honouring Ares above all other deities. The Ancient Greeks viewed Ares, the God of War, as an evil force and Hesiod says that their love of war was the reason that assured their mutual destruction. The fourth generation was the age of Heroes and Demigods. This is the time of the Trojan War and its legendary hero Achilles which Hesiod states is the race of humans before his own. Hesiod also mentions Cadmus, the legendary founder of Thebes, as well as Oedipus who became King of Thebes after vanquishing the plague-bringing Sphinx by solving its riddle. Hesiod praises this age of Heroes and offers the first view of an afterlife where fallen warriors live in a distant paradise ruled by Cronos. To the Ancient Greeks the domain of Hades was not a paradise and though it housed the souls and bodies of the departed they were mere shadows of their former self. A common theme in Greek plays and literature is the possibility of a return to life by escaping from the underworld of Hades. The playwright Euripides in his play "Alcestis" has Hercules rescuing the heroine Alcestis from the underworld after she has exchanged her life to save her husband from death. The comedy playwright Aristophanes has Euripides and Aeschylus, both deceased by the time of Aristophanes, competing in the underworld to settle the question of who is the greatest writer of tragedy in his play "The Frogs". The winner, as judged by Dionysus, will be returned to life from the underworld. Hesiod's paradise for heroes is not somewhere one would wish to escape from but it should be noted that the underworld was not regarded by the Ancient Greeks as Hell is to Heaven. This is reflected in the funerary practice of placing an obol (coin) in the mouth of the deceased to pay the ferryman, Charon, who transported the departed across the River Acheron. The Iron Race is Hesiod's own time and he spares nothing in describing the degenerate and corrupt nature of his contemporaries. This excerpt from the Evelyn-White translation of 1914 in which Hesiod describes the eschatological conditions that will lead to the destruction of the Iron Race highlights the universal themes comparable to modern religions and brings into focus the true moral aim of this agricultural manual for Persesː

The father will not agree with his children, nor the children with their father, nor guest with his host, nor comrade with comrade; nor will brother be dear to brother as aforetime. Men will dishonour their parents as they grow quickly old, and will carp at them, chiding them with bitter words, hard-hearted they, not knowing the fear of the gods. They will not repay their aged parents the cost of their nurture, for might shall be their right: and one man will sack another's city. There will be no favour for the man who keeps his oath or for the just or for the good; but rather men will praise the evil-doer and his violent dealing. Strength will be right and reverence will cease to be; and the wicked will hurt the worthy man, speaking false words against him, and will swear an oath upon them. Envy, foul-mouthed, delighting in evil, with scowling face, will go along with wretched men one and all.

The Greek peninsula resisted Roman rule, until it was organized into the Roman province of Achaea in 27 BCE by Augustus. Throughout history, conquerors have imposed their culture upon the vanquished, but the Roman annexation of Greece was perhaps one of history's most-influential exceptions to this rule. In the words of the Roman poet Horace, "Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit" ("Greece took captive her conqueror."). The Romans adopted nearly every aspect of Greek culture, allowing it to continue to thrive much as it had done for centuries. During this time period, Christianity began to rise, and Greece was one of the first areas of the Roman Empire to be heavily influenced by the new religion.

When Emperor Constantine I moved the capital of the Roman Empire to Constantinople in 330, Greece experienced a revival of its economic power, becoming one of the richest areas of the Byzantine Empire that was created by the Roman Empire's split in 305. After more than a thousand years of Byzantine rule, the Ottoman Empire in nearby Asia Minor began to rise in power, eventually capturing Constantinople in 1453. By 1460, Greece was under Ottoman control. As the Ottoman Empire gradually weakened, the Greeks were influenced by the growing nationalist movements throughout Europe during the early nineteenth century. In 1821, they rose up, and gained independence, leading to the creation of the modern Greek state.