History of Western Theatre: 17th Century to Now/American Post-WWII

"American playwrights...tend to show a steady downhill pattern in their careers...Their early (often quite autobiographical) work is their best, so that instead of showing a steady deepening and maturing of purpose and skill, their careers frequently become a rather sad and often frantic attempt to recapture the magic and lost innocence of first things” (Rosenberg, 1967 p 53).

Tennessee Williams

[edit | edit source]

Among American playwrights after World War II, Tennessee Williams (1911-1983) figures predominantly with "The glass menagerie" (1944), "A streetcar named desire" (1947), and "Summer and smoke" (1948).

"The glass menagerie" is “a play in which time becomes a central concern. So, Amanda’s present, in which she exists on the margins of society, surviving by pandering to those whose support she needs, is contrasted to a past in which, at least on the level of memory and imagination, she was at the centre of attention. Laura’s wilful withdrawal into the child-like world of her menagerie derives its sad irony precisely from the fact that it is a denial of her own maturity, of time. Even her ‘gentleman caller’ is momentarily forced to confront the discrepancy between the promise of his high school years (recalled by the photograph in a school yearbook) and the reality of his present life. Time has already begun to break these people as their fantasies and dreams are denied by the prosaic facts of economic necessity and natural process alike. Laura seeks immunity by withdrawing into the timeless world of the imagined, Amanda by retreating into a past refashioned to offer consolation. Tom alone seems to have escaped these ironies, at the price of abandoning those whose lives he had shared. But the play itself is the evidence that he has no more escaped that past than have his family. For why else does he summon this world into existence but for the fact that the past continues to exert its power, as the guilt engendered by his abandonment pulls him back to those whose sacrifice he had believed to be the necessary price of his freedom” (Bigsby, 2005 p 268). The play "translated a depression story into a sensitive character drama. It gave evocative realization to the ineffectual struggles of a small family- a seedy Southern woman who clung to the memory of better days, her painfully shy crippled daughter for whom the mother tried to find 'a gentleman caller', and a restive poetic son who, tiring of perpetual nagging, ran away from home after the tragi-comic fiasco of bringing an already affianced young man for his sister" (Gassner, 1954a, pp 698-699). Berkowitz (1992) suggested that "rather than rejecting Amanda and Laura as misfits, we [should] cherish them as beautiful alternatives to the ordinary" (p 89). However, such an attitude reduces the sadness inherent in Laura's failure to find her man. "Laura retreats into her world of illusion, in which a menagerie of glass animals stands as symbol of her fragility. Poignantly and tenderly drawn, Laura has little chance of a life independent of her overbearing mother, who thrives on memories of a romantic youth in which she was the lady of choice to a gaggle of gentleman callers. The play, which is offered as a memory, is both powerful and sad, capturing the spirit and the longing of one who now lives on the edge of poverty but who has known a finer life" (Schlueter, 2000, p 299). “The tender insight into character, the delicate symbolism, the familiarity with the environment, and the sustained tone of elegy were like a revelation of what superb theater could be” (Atkinson, 1974 pp 405-406). “Laura is incapable of adopting the role of the belle. Her intense sexual frustration combined with her father’s abandonment and her mother’s tyranny have produced such a fragile sense of self that she is utterly incapable of the kind of projection required in the coquettish behaviors Amanda prescribes...Amanda understands the social and economic realities of their world, and, by modelling the role of the belle, she attempts to teach her daughter an important survival technique” (Hovis, 2011 p 179). Because of the tediousness of his job, Tom rejects "society's demands on working, self-sufficient, upwardly mobile young people" and so abandons mother and sister in favor of his own happiness (Greenfield, 1982 p 122). Such critics have an overly negative opinion of Jim in that "his values hold out a false hope for a wonderful America" (p 123) when his values have no direct influence on the plot. Likewise, Fleche (1997) finds Jim's associations funny when he equates knowledge with money and power; there is also a fear that "science's explanations imply an insidious will to mastery" (p 85). Granted that Jim represents a false hope for the Wingfields, that does not mean his ideas, irrelevant to Laura's fate, are false. A positive view of Jim was expressed by Krasner (2006) in that Jim “exudes optimism”, “amuses everyone with his upbeat mood”, ‘believes in the future”, “does not let the Depression discourage him” (p 32).

"The shock of A Streetcar Named Desire when it was first staged lay in the fact that, outside of O’Neill’s work, this was the first American play in which sexuality was patently at the core of the lives of all its principal characters, a sexuality with the power to redeem or destroy, to compound or negate the forces which bore on those caught in a moment of social change” (Bigsby, 2005 p 277). The play is “a modern tragedy without a hero or a villain; each protagonist is also an antagonist, and so instead of a hero’s journey, we are offered rather a raw and painful view of human misunderstanding” (Keith, 2018 p 174). The play “placed in opposition to Stanley Kowalski at the beginning of play, [Blanche as] the aristocrat who condescends to the plebeian when she is not actually scorning him...Stella is fortunate...as ordinary people, who have an aptitude for the ‘blisses of the commonplace’, are fortunate. Blanche, on the contrary, cannot renounce her view of herself as a rare individual...One cannot help pitying [Blanche] and also laughing at her because the life she affects to despise seems so invincibly alive while her eyes are fixed on a decadent past. But pity claims priority because her helplessness is so palpable, and because she is so evidently concealing a wounded past” (Gassner, 1965 pp 375-381). “Her consuming need...is to make herself and others aware of her refinement. She is concealing her tawdry past of alcoholism, incontinence, and common prostitution” (Gassner, 1954b pp 355-356). "Before Blanche’s arrival, Stanley and Stella enjoyed, through compromise, an intimate, happy marriage, and in this could be said to have achieved a degree of civilization, of humanity, unequaled by the DuBoises of Belle Reve, a distortion of “beau rêve”, beautiful dream; before Blanche’s arrival, Stanley also enjoyed the best of friendships with Mitch, who in some ways is as sensitive and in need of understanding as Blanche" (Cardullo, 2016 p 90). When Blanche arrives via "A streetcar named desire", Stanley immediately resents her presence, viewing her as a threat in reminding Stella "of their past prior refinement and sophistication" (Krasner, 2006 p 41). "Blanche stands for idealism, culture, purity, and the love of beauty, but also for falsehood, fantasy, weakness, and the rejection of unpleasant reality" (Berkowitz, 1992 p 90). Blanche is the southern belle clashing in the new south, a more hostile environment than the old south she is used to, when “ante-bellum days represent an ideal of gracious living, an ideal that includes a code of personal honor extending into every area of his experience...So Blanche appears high-strung and sensitive, on one hand, but exploiting the Kowalskis’ resources and willing to destroy her sister’s marriage, on the other. As in her youth, she plays the coquette, requesting Stanley to button up her dress, teaching Mitch how to present flowers by bowing first, dropping a French word or two. But when a tempting newsboy enters, coyness turns to downright kissing. Yet clinging to the old ways governs her mind when she refuses to bed with Mitch, disillusioned after Stanley’s report of her past conduct, even when pre-nuptial copulation appears as her last hope. The situation worsens when instead of submitting to Mitch’s love she is raped by Stanley, the opposite pole of southern gallantry. Nevertheless, at the end, the intruding imposter appears worthy of pity through accumulated maledictions: husband’s suicide, family deaths, loss of Belle Reve, job dismissal, and send-off to a psychiatric institution" (Porter, 1969, pp 154-173). The newsboy scene's "real poignancy, is its evocation of Blanche’s own lost innocence as well as her imagination and depth of feeling- an innocence or purity suggested by her very name (the feminine form of the adjective 'white' in French), which identifies her with the achromatic color white as opposed to Stanley’s primary colors and by her astrological sign, Virgo (for 'virgin'). We may see Blanche in the negative light of seductress here, but we should also see her in a positive light, as one who recognizes her own lost innocence (not accidentally, in the figure of a young man who recalls Allan Grey) and responds to it effusively. This is one way of explaining her turning to a seventeen-year-old boy for an affair in Laurel after her many 'intimacies' with men at the Hotel Flamingo: in turning to a boy, Blanche was attempting to return to her own youth when, with Allan, she 'made the discovery- love. All at once and much, much too completely” (Cardullo, 2016 p 100). "More than any major character in the early postwar years, Blanche embodies the conflicts of a changing world. A lover of poetry and music and ballroom taffeta, Blanche stands as a fading tribute to refined life unable to survive in Stanley Kowalski’s crude and raucous world. Herself a complicated woman, Blanche has memories of an ideal she may never herself have known and finds refuge in alcohol and lies" (Schlueter, 2000, p 300). “Stanley’s reference to Blanche as a ‘queen’...reveal that his resentment stems at least in part from class envy...In his relationships with both Blanche and Stella, Stanley longs to reduce them to his level, as his remark about dragging Stella ‘down off them columns’ indicates. Alternatively, Stanley posits himself as royalty” (Harrington, 2002 p 71). “The brutes have won...yet one must remember that the brutes are not without some redeeming qualities. Stanley has displayed intense loyalty to his friends, genuine love for his wife, and a variety of insecurities beneath his aggressive manner. The other men have displayed loyalty to Stanley and Mitch has shown much sympathy and understanding” (Adler, 1994c p 2576-2577). Mitch’s rejection of Blanche is a cruel counterpart of her rejection of her homosexual husband (Featherstone, 2008 p 265). “Blanche finds her own version of Stanley in Mitch, who, although of the same working-class background as Stanley, has ‘a sort of sensitive look’ and seems to her ‘superior’ to his other friends. Mitch becomes the ‘cleft in the rock of the world that I could hide in’, and Blanche admits to Stella that she wants ‘to deceive him enough to make him want me’. The deception involves her acting out the tradition, refusing any sexual activity beyond a kiss because, she tells Mitch, she has ‘old-fashioned ideals’. Williams makes sure that the audience is aware of Blanche’s acting, as she rolls her eyes when she says this, and, perhaps more dangerously, compares herself to the most famous courtesan in literature, Alexandre Dumas fils’s Camille, when she tells him ‘Je suis la Dame aux Camellias! Vous êtes Armand.’ and after Mitch assures her that he doesn’t understand French, asks him, 'Voulez-vous couchez avec moi ce soir?’ [Would you like to sleep with me this evening?], which it wouldn’t take a great knowledge of French for someone who frequents the French Quarter of New Orleans to understand. There is a dangerous flirtation with self-exposure in Blanche’s behavior with Mitch that is related to her guilt over her behavior with Allan and her reckless promiscuity subsequently. Nonetheless, she succeeds in deceiving Mitch until Stanley discovers her past, with its ‘intimacies with strangers’, and she is forced to admit it to Mitch, who finds her no longer ‘straight’ or ‘clean enough to bring in the house with [his] mother’ despite her plea, ‘I didn’t lie in my heart’” (Murphy, 2014 p 78). "There is a doubleness about Blanche’s involvement with Mitch. In each case, she seems less interested in the affair for its own sake than in the ritual of romance in its relation to her first love, the defining relationship of her life...Similarly, she recognizes the possibilities for imaginatively evoking the past when she flirts with the newspaper boy” (Hovis, 2011 pp 178-182). “Blanche...calculates the effect of her performance on her various audiences...By contrast, Stella dispenses with the role of belle and speaks candidly to her husband, trusting him to respect her openness with commensurate tenderness and honesty. Stella fled Belle Reve and the example of her older sister perhaps because she recognized the dangers of performance. Unfortunately, Stella fails to recognize the dangers of not performing. “The duality of Dionysius whose gift of wine can bring both pleasure and madness permeates this world. Similarly, the play’s Dionysian sexual passion leads both to ecstasy (desire) and destruction (cemeteries) while the inexorable passage of time juxtaposes Blanche’s poetic dream of Elysian Fields with the decay of the Quarter. The plot embodies the complex structure and climax of Aristotelian drama, but Williams alters its proportions to his own dramatic ends. While the play fits no standard definition of tragedy, Blanche’s struggle with Stanley endows her with the status of a tragic figure. Intro- duced as an unsympathetic and pretentious snob, she becomes more sympathetic as she mentally disintegrates over the play’s 11 scenes. Following the rising action of scenes 1–6, the brutal reversal stretches over scenes 7–9 culminating in the violent climax when Stanley rapes Blanche at the end of scene 10. The painful extended denouement of scene 11 reveals the irrevocable change in the lives of the central characters” (Berwind, 2015 p 242). Unlike Blanche’s, Stella’s passivity is real and Stanley takes advantage of it by intermittingly bullying her and by virtually denying her a voice in the affairs of their home. He invites his drinking buddies over for poker nights and ignores her objections. He physically and emotionally abuses her, even when she is pregnant- and afterward, to the chagrin of Blanche, Stella returns home to forgive and make love to her husband. When Stanley ultimately betrays Stella’s trust by raping her sister while Stella is in labor at the hospital, Stella passively accepts Stanley’s denial of Blanche’s report and even acquiesces to his demand that her sister be institutionalized for her delusions...Stella is confronted with the choice of choosing her husband or her sister. Stella chooses Stanley (Lewis, 1965 p 63). “Stella’s concern for her sister on the one hand and her content with her life with her loutish husband are objective and understanding” (Atkinson and Hirschfeld, 1973 p 194). "In contrast to her sister, Stella already has her man, a southern belle content to submit to her husband’s lack of manners and to attend to household affairs in a degraded context. Stanley’s crude taste for say-what-I-think behavior extends to mother-dominated Mitch, who when heading towards the bathroom hears his friend say: 'Hurry back and we’ll fix you a sugar-tit.' For entertainment, he wants sex and 'getting the colored lights going', akin to a people’s taste for fireworks and kaleidoscopes. There is ironic contrast between words and acts. While Stanley dirties his sister-in-law’s reputation, Blanche takes a bath" (Corrigan, 1987, p 31). "When Blanche leaves for the insane asylum, and the oblivion attending it, at the end of Scene 11, Stanley remains behind with Stella: his way of life thus appears to have won out over his sister-in-law’s. But it is not that simple. Life for the Kowalskis will never be the same after Blanche’s departure, and Williams provides plenty of evidence for this conclusion in the final scene of the play— evidence that, once again, has hitherto mostly been ignored by critics. If the Mexican woman of scene 9 is the symbol of death, desire, and the past in A Streetcar Named Desire, then the newborn child of Scene 11 is the play’s symbol of life, maternity, and the future for Stella, but not for the paternal Stanley. Stella’s absence from both scene 9 and Scene 10 while she is giving birth, coupled with her reappearance onstage in scene 11, serves to distance her in our minds from her husband and to pressure her relationship with him beyond the perimeters of the play. That Stella does not once speak to Stanley in the last scene of A Streetcar Named Desire (even when addressed by him one time) is indicative of the essential silence that will permeate the rest of their lives together" (Cardullo, 2016 p 97).

"Summer and smoke" as a title "comes from [Hart] Crane’s Emblems of Conduct: ‘By that time summer and smoke were past/Dolphins still played, arching the horizons,/But only to build memories of spiritual gates’. This title from Crane’s work evokes the nostalgia of a world long past its apogee and now declining. Williams’s clear intent is further reinforced in the only passage where Crane’s phrase is echoed, when Alma describes her former “Puritan” self (and by inference all those who lived by this code), late in the play, as having ‘died last summer, suffocated in smoke from something on fire inside her’” (Debusscher, 2005 pp 75-76). “Considered alone, the story elements show Williams the potential author of banal novels...The essential worth of Summer and Smoke lies in its integrity as a play. As such it is a compound of story, plot, characterization, atmosphere, mood, and an attitude of sultry irony” (Gassner, 1960 p 220). Alma, whose name evokes the soul, rejects the body in favor of the soul, whereas John does the reverse (Murphy, 2007 p 181). "'I am more afraid of your soul than you are of my body,' he confesses. They never meet because at the moment when Alma accepts the body, John has accepted Nellie, who seems to incorporate body and soul together. “The play reveals the failure of Alma to find satisfaction of both sex and spiritual values in the man she loves. Her lover is as frightened of her soul as she is of his body; he could not feel decent enough to touch her. Since she cannot find true love, she destroys her spiritual quest and gives herself to the first travelling salesman she meets” (Lumley, 1967 p 187). According to Boxill (1987), “whereas Alma’s change is fundamental, John’s is merely developmental. He pulls himself together after sowing his wild oats. She falls apart after losing the love of her life. The minister’s daughter now pursues a nightly quest for sex with strangers” (pp 98-99). But can she not sow her own oats? Gassner (1954a) understood the play as implying that Alma "loses her chance of love as a result of too much fastidiousness...Driven to desperation by ironically losing the man she had kept at a distance too long, Williams’ heroine makes an assignation with the first footloose person she meets. Frustration, painstakingly motivated by her sensitivity and her unhappy family life, starts the idealistic girl on a road that may have many widenings but will ultimately bring her to complete moral, as well as psychological, bankruptcy" (p 741). Ganz (1965) offered an opposite view of Alma's end. "Like Blanche [Dubois of "A streetcar named desire"], she is condemned to be tormented by the urges she had turned away from, and like Blanche she turns to promiscuity, but because her sin has been somewhat mitigated by her realization of it, there is a suggestion at the end of the play that the travelling salesman she has picked may lead her to salvation rather than destruction" (p 210). “Unhappily, [Alma] has grown up in a sheltered environment, mostly in the company of her elders. Years of dull church entertainments and of her father’s dreary sermons have brought alma few contacts with the less inhibited citizens of Glorious Hill. Because of her narrow training, she believes that man’s nature is coarsened by an animality which only his spiritual nature can control. Actually, she herself possesses a truly deep sexual nature which struggles against her protected and arid way of life...For John, too, there is the problem of a ruinous loneliness...He resembles Alma in his need for a warm and stimulating association with a loving woman who understands his real temperament” (Herron, 1969 pp 363-364). “Alma...moves from her rarefied world of genteel art, idealism and hysteria to a less idealized world of drugs and assignations with travelling salesmen. At the same time, John moves in the opposite direction, from dissipation in the violent shadows of the moon lake casino to a career of hard work, heroic medicine and cloying domesticity...[When] Alma and John consider the statue of Eternity...the word at the base of the statue is worn and can no longer be read...It is the juvenile Alma who introduces John to the physical pleasures of tactile understanding...Williams suggests that the way we encounter the boundlessness of the sublime is not by repudiating sexuality but by accepting it...[At the conclusion]...John, having rebelled against patriarchy, suddenly finds his patriarchal impulses become reality with his father’s death. After this, John assumes the patriarchal position and becomes the good doctor, husband and model citizen who repudiates Alma’s advances [as a fallen woman]” (Gross, 2002 pp 93-98). In yet another interpretation of the ending, we have “John marrying the conventional Nellie and Alma seducing a salesman, suggesting that the ultimate winner in every contest is a conservative, business-minded America” (Abbotson, 2010 pp 50-51). Alma “is afraid to confer her love for Buchanan for fear that its mere expression will destroy it. But the irony around which the play is constructed derives from the fact that Alma comes to be convinced of the need to complete her life by conceding the existence of a physical sexuality at precisely the same time that Buchanan learns the insufficiency of the merely physical” (Bigsby, 1984 p 69). “In a schematic way, the two characters change places as Alma realizes the sexual nature of her attraction to John and John comes to see that, despite the fact that there is no ‘soul’ in his anatomy chart, Alma is right that love can be something beyond mere sex because ‘there are some people...who can bring their hearts to it, also- who can bring their souls to it’. Alma first rejects John’s sexual advances because he is ‘not a gentleman’, maintaining her ideals against his sensual desire. But John undergoes a change as a result of his relationship with Alma, and though she ultimately finds that ‘the girl who said no...died last summer- suffocated in smoke from something on fire inside her’, she also finds that ‘the tables have turned with a vengeance’ when he says that he couldn’t have sex with her now. He tells her, ‘I’ve come around to your way of thinking, that something else is in there, an immaterial something–as thin as smoke...and knowing it’s there- why then the whole thing- this- this unfathomable experience of ours- takes on a new value, like some– some wildly romantic work in a laboratory’. And he realizes that 'it wasn’t the physical you that I really wanted,’ but a 'flame, mistaken for ice. I still don’t understand it.’ The symbolic scheme and the psychological struggle come together when John rejects Rosa Gonzalez, to whom his attraction is purely sexual, and becomes engaged to Alma’s former music pupil, Nellie Ewell, the daughter of a somewhat notorious woman who picks up salesmen at the train depot. At the end of the play, Nellie has escaped from her mother and has been educated at Sophie Newcomb College. She combines a straightforward, vibrant, and youthful sexuality with a reverence for Miss Alma, whom she calls ‘an angel of mercy’, and the influence Alma has had both on her and on John. John’s future looks to be stable and bourgeois, a conventional if loving marriage which will clearly include a healthy sexual element. Alma’s future, on the other hand, is less conventional. The final scene, in which she picks up a young salesman in front of the fountain, is more ambivalent. Having taken one of her sleeping tablets, which makes her feel ‘like a water-lily on a Chinese lagoon’, she prepares to go off with him to the Moon Lake Casino, the scene of her earlier rejection of John’s advances. Clearly she has different intentions this time, but the meaning of the play’s ending is ambivalent. On the one hand, she is walking in the footsteps of Mrs Ewell, and is probably about to be ostracized by the town. If she continues this way, as Stanley Kowalski says of Blanche DuBois, her future is ‘mapped out for her’. On the other hand, she has accepted a part of her nature whose denial had reduced her to painful loneliness, hysteria and debilitating panic attacks, and seems for the first time to be at peace. As she jokes with the young salesman, she laughs 'in a different way than she has ever laughed before, a little wearily, but quite naturally’. The overall sense at the end of Summer and Smoke is of integration and peace for its two tortured main characters, as well as loss. In the terms of Williams’s symbolic scheme, the fierce flame of spiritual and sexual tension that glowed between them is quenched, leaving the smoke” (Murphy, 2014 pp 70-71).

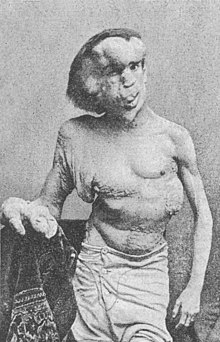

In general, Feranow (2007) described Williams' plays as "character-driven drama in which the plot is submerged beneath the cumulative events in the lives of the characters. Plot points emerge suddenly, often surprisingly, and reveal hitherto unseen workings of the characters' psyches. This branch of realism is often identified with Chekhov...Added to the Chekhovian structure is the mark of Williams- a romantic attraction to the grotesque, the beautiful spirit in an ugly body, compassion for the broken, the miserable, and the deformed. The plays are neither unrelievedly grim nor the damaged characters doomed, as one would expect in a work by Sartre or Genet. The plays suggest a vague hope, if not redemption, resulting from the characters' suffering" (pp 425-426).

"The glass menagerie"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1930s. Place: St. Louis, USA.

Text at https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.2826 https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.234940 http://www.pval.org/cms/lib/NY19000481/Centricity/Domain/105/the_glass_menagerie_messy_full_text.pdf

During an evening at home with her son, Tom, and her daughter, Laura, Amanda Wingfield recalls her youth spent in the south, at Blue Mountain, when young women knew how to talk and gentleman callers were plentiful. She chaffs her daughter about the absence of gentleman callers for her this evening. "What, not one?" she queries ironically. The following day, Amanda is astonished, abashed, and humiliated on learning that Laura, whom she thought a student at a business college, has been spending all that time walking around the city. Laura vomited during a typing speed test and never returned. On his part, Tom often goes to the movies after drudging all day in a warehouse to support the family. Amanda asks him to find a man his sister might date. As her brother, he should be willing to help, because Laura does not appear to be apt to work, nor is she competitive for men's attention. She only seems interested in attending to her glass menagerie and listen to phonograph records. Tom asks a shipping clerk at the warehouse, Jim O'Connor, to come over to his house for dinner without mentioning Laura. Jim already makes more money than he does and appears to have a good future. Amanda queries Tom about Jim's habits and at length is satisfied. On the alley-way landing, "a poor excuse for a porch," according to Amanda, she hopes for the best. Before Jim arrives for dinner, Amanda tries to stuff Laura's breasts with a "deceiver", but she declines to use it. A perturbed Laura recognizes Jim as the boy she once loved in high school and has often thought about ever since. As he enters the house, she panics, leaving the room precipitously in fear. During the course of the evening, Amanda does most of the talking. She has herself prepared salmon but pretends it is Laura's work. When Laura is compelled to come back in, she feels faint and rests on the sofa. Suddenly, the lights go out because Jim has neglected to pay the light bill, spending instead for a shipman's union dues as a first step in moving away, because he does not want to be like those who look at movies instead of moving. After dinner, Laura is left alone with Jim. At ease with the world, Jim thinks she obviously lacks self-confidence. Laura shows him her glass menagerie. While hearing music from the dance hall across the alley, Jim proposes that they dance. While they dance, he clumsily bumps against the glass animals, knocking the unicorn to the floor and breaking off its horn. Jim is very sorry, but Laura says it does not matter. "Now it's just like the other horses," she concludes. As they grow friendlier, Jim reveals in passing he is engaged to be married. On learning this, Amanda is outraged at her son for not knowing in advance about Jim's engagement. After leaving the family and remembering that night's events, Tom advises his imaginary Laura to blow out her candles.

"A streetcar named desire"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1940s. Place: New Orleans, USA.

Text at https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.86608 https://archive.org/details/twentyfivemodern001705mbp

Blanche DuBois arrives at the house of her married sister, Stella Kowalski, to say that she lost their ancestral home in a mortgage, and has no place to stay. Stella's husband, Stanley, is suspicious of his sister-in-law's version and promises to investigate. Blanche meets Mitch, an unattached friend of Stanley at a poker game, and they sympathize. During the course of the night, as the women listen to music, a drunken Stanley tosses out the radio in the street and hits his wife, who first seeks refuge with a neighbor but then, to Blanche's amazement, goes back to him. He confronts Blanche after discovering that she was a regular at the Flamingo Hotel in the town of Laurel, a brothel, but then pretends to believe his informer must have been mistaken. Alone in the apartment, Blanche lets in a young man who collects money for a newspaper, and flirts with him. Despite this interlude, she and Mitch grow fond of each other. She tells him an anecdote from her youth, when she married a man only to discover he was a homosexual. He killed himself and she was left feeling guilty over the event. Mitch needs someone because his cherished mother is near death and he has no one else. On Blanche's birthday, Stanley informs Stella about her sister's wanton tendencies in Laurel. Stella calls her merely "flighty" and blames men's behaviors for the way she behaves. Undeterred, Stanley gives Blanche a one-way bus ticket as a birthday gift. Having learned from Stanley of Blanche's misrepresentations, Mitch does not at first show up at her party. When Mitch finally arrives, he attempts to sleep with her, what he "has been missing all summer", but his brutality makes her cry out until he leaves. With his wife in a hospital bed soon expected to give birth, Stanley chats amiably with Blanche but then his real intention becomes clear as he moves towards her in silk pajamas and carries her off to bed. The Kowalskis, knowing Blanche has no other place to go, alert a psychiatric institution about her plight. A doctor and a nurse arrive to take her away. She is disoriented and begs for sympathy. "I have always depended on the kindness of strangers," she affirms while being led away. Suspecting that Stanley had raped her sister, guilt-ridden Stella nevertheless chooses to continue living to her husband than her sister.

"Summer and smoke"

[edit | edit source]Time: 1910s-1920s. Place: Glorious Hill, USA.

Text at https://pdfcoffee.com/summer-and-smoke-by-tennessee-williams-pdf-free.html

Alma seeks to attract her neighbor, John, a handsome medical doctor, just arrived from a prestigious university. She is mocked by her demented mother, who waltzes before her and chants: "Alma's in love, in love." Alma manages to get John to a culture club, but he remains in the club only briefly. In difficulty to sleep, she consults John's father, Dr Buchanan, at 2 AM, but John prevents her from seeing him, diagnosing loneliness as her main trouble. One day, the two friends go out near a gambling casino, where he suggests that the two retire inside a rented room. But the suggestion offends her. "What made you think I might be amenable to such a suggestion?" she coldly asks. She hears a rumor about how John intends to marry the daughter of the owner of the casino, Rosa Gonzales, after having lost a good deal of money, that being the only way to recuperate his losses. A desperate Alma calls Dr Buchanan on the telephone to warn him of his son's intention. As a result, Buchanan orders Rosa and her father out of his house and insults them. Losing control of his anger, Gonzales shoots him to death. Racked by feelings of guilt, Alma confesses to John that she was the person who made the call. Though recognizing that Alma loves him, John dismisses her, specifying that to him she represents "nothing but hand-me-down notions, attitudes, poses". He leaves town to pursue medical research and succeeds in notable discoveries. On his return, he engages himself to marry Nellie, a musical student of Alma's. Nellie is grateful to Alma, because her future husband revealed the fortunate influence she has had on him. Alma seeks John out one more time, now willing to experience life in the flesh after being reminded how she once refused him. "But now I have changed my mind," she says, "or the girl who said 'no' she doesn't exist any more, she died last summer- suffocated in from something on fire inside her." But it is too late. While Alma has come round to his way of thinking, he has come round to hers. Alone in a winter park, she initiates conversation with a stranger and they head together towards the casino.

Arthur Miller

[edit | edit source]

Arthur Miller (1915-2005) gained prominence with "Death of a salesman" (1949) and "The crucible" (1952).

To understand a play of the 1940s, one must be reminded that "'Death of a salesman' is set in a society that does not provide 'job security, health benefits, or provisions for retirement'" (Featherstone, 2008 p 230). Death of a Salesman was conceived as an expressionist play…The play’s eye was to revolve from within Willy’s head [as he visualizes the past] (Gottfried, 2003 p 122). Willy can be seen as a victim of the idea that money is the reward of virtue, as expressed by the clergyman, Horatio Alger (1832-1899), focal-point of the Protestant ethic, as well as the idea that wealth is essential to the growth of civilization, as expressed by the essayist, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882). “In Alger...the key to success is not genius or gentle breeding but character, enabling the common man to succeed in this life and the next as well as his children’s lives should he transmit his values. It is critical that the salesman, the link between producer and consumer, be well liked because he must sell himself as well as his products. Believing up to the end in financial success ideology, he commits suicide to give Biff a chance to succeed" (Porter, 1969 p 130). “Loman has been unable to learn that business ethics, the morality of his work-community, oppose the traditions he assumed were still in action: the personal ethic of honour, the patriarchal nature of a basically benevolent society and family, and neighbourhood relations” (Mottram, 1967 p 134). The force of the play "continues fitfully to grasp at us: the idea of a man who has sold things without making them, who has paid for other things without really owning them, who is an insulted extrusion of commercial society battling for some sliver of authenticity before he slips into the dark. And battling without a real villain in sight. Willy’s boss, Howard, comes closest to that role when he fires or retires Willy for poor performance, but Howard’s failing is not ruthlessness; it is lack of understanding" (Cardullo, 2016 p 163). “From the conflicting success images that wander through his troubled brain comes Willy’s double ambition to be rich and to be loved. As he tells Ben, ‘the wonder of this country is that a man can end with diamonds here on the basis of being liked’. Willy’s faith in the magic of personal attractiveness as a way to success carries him beyond cause and effect to necessity; he assumes that success falls inevitably to the man with the right smile...Willy “regularly confuses labels with reality. In his last scene with his son, Biff, Willy cries out: ‘I am not a dime a dozen’...The strength and the pathos of that cry is the fact that Willy still thinks that the name should mean something. It is effective within the play because we have heard him imply that a punching bag is good because, as he says: ’It’s got Gene Tuney’s name on it’” (Weales, 1967a pp 87-88). Willy “not only views the world in terms of what people think of him but also in terms of what his sons think of him. He desires not only the respect of his sons, particularly Biff whom he has failed, but he wants them to like him. In his worldview, likability is the most marketable commodity and leads to self-worth and economic and social advantage. Willy’s association of likability with self-worth becomes clear in the exchange with Biff that leads to the father’s suicide. Following a day of failed attempts to ensure their financial futures, Biff explodes to his father about the pretence and ‘hot air’ that has compensated for genuine success and authentic character. ‘I am not a leader of me, Willy, and neither are you,’ Biff famously remarks. ‘You were never anything but a hard-working drummer who landed in the ash can like all the rest of them’ (Robinson, 2018 p 190). "Willy Loman's own experience proves that...success is...not guaranteed to the well-liked or even the hard-working...Despite his growing realization that he does not want what the world calls success, Biff can only call himself a worthless failure for not having achieved it" (Berkowitz, 1992 p 80). Money as a reward for virtue is sometimes termed "Willy’s law". Driver (1966) complained that Willy’s law is not countered by another character representing some sort of “law of love” (p 111), because Biff only seeks in trying to make his father understand that his law is false without showing him a new one. Likewise, Bernard has only negative advice for Willy: 'But sometimes, Willy, it’s better for a man just to walk away.' Loman...never knew who he was. Lear did” (Kitchin, 1966 p 79). von Szeliski (1971) criticized the meager ambitions and goals in modern attempts at tragedy relative to the Renaissance, commenting sarcastically that "'not being able to walk away' is Miller’s idea of tragedy" (p 173). Moreover, in the view of Stambusky (1968), Willy Loman fails as an Aristotelian figure of tragedy because his emotional stature is beneath that required and because, unlike Biff, who cries out that he is "a dime a dozen", he never recognizes his flaw, equating success in life with success in getting money and estimating popularity among one’s peers of more importance than richness of intimate relations (p 100). Freedman (1971) agreed that Loman never discovers what his flaw is. “All that Willy Loman wants is the middle-class apotheosis of success: a mortgage paid off, a car clear of debt, a properly working modern refrigerator, an occasional mistress, sons 'well-liked' if uneducated and aimless” (p 45). “Death of a Salesman is an admirable blend of pathos and satire...The play is non-tragic...simply because Willy Loman lacks the ferocity which is an essential ingredient of tragedy, and because his driving illusion is one which we do not respect...His identification of success with a cheering crowd...we at least profess to scorn. Willy Loman evokes pity...but he cannot evoke terror” (Gascoigne, 1970 p 177). Other critics have disagreed. “Willy Loman makes himself a tragic hero of sorts by his abundant capacity for suffering. He asserts a sort of tragic or semi-tragic dignity, with his fine resentment of slights and his battle for respect as well as for self-respect. He makes a claim for tragic intensity by his refusal to surrender all expectations of triumph for and through his sons...The thing that Miller could not do...is to give Willy an interesting mind...with a related limitation of language...that makes me contemplate the use of such a term as low tragedy” (Gassner, 1960 pp 63-64). “The fundamental enlightenment must be for the audience, whether or not the tragic character achieves it for himself” (Gassner, 1954b p 74). “Willy’s attitudes towards his work undermine his capacity for self-knowledge...What Willy sells is never stated, so that he can represent all salesmen. Being well-liked is so critical to him that instead of selling only products, he sells his soul. Linda is puzzled over her husband’s suicide when the house is paid for and he only needed ‘a little salary’; it is because of the work pressure he submitted himself to, which consigned him as a failure. Although Willy wants his sons to emulate Ben’s success, he is floundering, uncertain how to teach his sons to succeed in the world, and during Ben’s visit they are caught stealing lumber from a construction site with Willy’s approval” (Greenfield, 1982 pp 79, 102-111, 233-234). “Willy’s patriotic rhetoric about American great- ness is contradicted by his own occasional frustrated anger at the built-in redundancy of the things he has struggled to acquire and that define his life. And then there is human redundancy, the fact that individual aspiration to business success as the highest good is contradicted by the system’s readiness to disgorge anyone and anything that no longer serves the all-powerful profit motive. Above all, the play insists that the commitment to an ethos of success thus defined obscures and subverts the fundamental value of love, either between parent and child or on a larger scale, as a genuine sense of social relatedness. Though Miller has Willy achieve at least a partial recognition of his son Biff’s love for him in spite of everything, the play ends on the tragic irony that he can only conceive of furthering his dreams for them by pursuing his commitment to financial success to its reductio ad absurdum, committing suicide so that his family can claim the insurance money” (Crow, 2015 p 172). The play “is a masterpiece of concentrated irony and controlled indignation...Biff, the recalcitrant one, draws his rebellion in Miller’s best manner, more from disgust at one of his father’s infidelities than from any reasoned objection to what he has been taught. Nothing short of a slur on that universal idol, the American mother, could have roused this character from his mental lethargy” (Kitchin, 1960 p 62). “Willy has a supportive wife who makes her husband’s self-delusion possible. She is a woman who loves her husband and commits herself to him even at the expense of her personal integrity, the nourishing mother-wife without whom neither head of the household could survive…Linda fortifies Willy with encouraging words and praise, reviving his spirits whenever they sag. When Willy’s commissions are not so substantial as they might have been, even in earlier years, Linda allows him to pretend he made more than he did and praises him for his achievement. When Willy tells her how he lost his temper and hit a salesman in the face when the man called him a walrus, Linda does not reproach him for his behavior but tells him that, to her, he is the handsomest man in the world. When Willy keeps driving the car off the road, though she knows of his death wish, she tries to excuse the action by suggesting he needs an eye examination or a good rest. Even when Linda discovers the rubber hose in the basement, hidden beneath a pipe for the day that Willy can no longer endure, the faithful wife neither confronts him nor removes the hose, knowing Willy depends on her thinking that his strength cannot falter” (Schlueter and Flanagan, 1987 pp 57-66). Hobson (1953) disagreed with critics' complaints about the play's common speech, pointing to the final scene when, bewildered, Linda says of her dead husband that "he only needed a little salary." "No man needs a little salary," Charley responds. "He’s a man way out there in the blue, riding on a smile and a shoeshine. And when they start not coming back, that’s an earthquake." Hobson found the rhythm “moving and true” and on Charley’s comment on the theme of man cannot live on bread alone he wrote: "I never heard in an American play something wiser, better said, or better worth saying” and that Linda “touched depths of sadness and reached heights of royalty that passed beyond royal and purple speech” (Hobson, 1948 pp 122-123). “In the pastoral world that Willy Loman creates in his mind, there is no real place for women, precisely because this is the 19th century world of his father and grandfather. The subordinate role of women is thus less a product of Miller’s incapacity than of the necessities of a play which examines Willy’s imperfect grasp of reality” (Bigsby, 1985 p 421). “Death of a salesman” “would have represented an attack upon the system- and a telling one at that- had Mr Miller elected to reverse the situation and make Charley the central character and Bernard a failure” (Gardner, 1965 p 125).

On the subject of marvels and superstitions, Bacon wrote in “The advancement of learning” (1605): “neither am I of opinion that this history of marvels, that superstitious narrations of sorceries, witchcrafts, dreams, divinations, and the like, where there is an assurance and clear evidence of the fact, be altogether excluded. For it is not yet known in what cases and how far effects attributed to superstition do participate of natural causes: and therefore howsoever the practice of such things is to be condemned, yet from the speculation and consideration of them light may be taken, not only for the discerning of the offences, but for the further disclosing of nature” (1957 edition, p 36). "The crucible" "is freely based on the notorious witch trials of 1692 in Salem, Massachusetts, when nineteen honest citizens were hanged for dealings with the devil, and innumerable others imprisoned, in a panic started by hysterical young girls who testified themselves possessed through the satanic influences of their neighbours...For sheer cruelty and stupidity, the Salem witch trial must take its place among the most degrading spectacles of apparent civilisation. And it is Miller's strength that he has given the material dramatic shape, and by selecting three key characters (two of them created, one the malevolent girl Abigail Williams- historical) ignited our interest not only in the theme but in individual psychology...The mixture of exorcism, revivalist hysteria, pretended possession and blinded justice, combining to further private grudges and public fanaticism, is presented by the dramatist with masterly excitement...The language has a biblical ring of metaphor, graphically in period; and though the play at the end, with Proctor's recantation, comes near enough to Saint Joan to make us conscious of its principal lack- Shaw's intellectual grasp of the wider issues- its dramatic impact, failing only here, has already been made and sustained with unremitting power" (Williamson, 1956 pp 54-55). Differences between history and play included changes in the ages of two characters. “The real Abigail Williams had been 11 years old and John Proctor in his 60s. Miller decided to make her 17 and Proctor 30ish” (Gottfried, 2003 p 199) to introduce a romantic element in her and a guilt element in him for having committed adultery with her. “The fierce narrative thrill of the action depends on Mr Miller’s mastery of period dialogue. “The language is a rich and stageworthy mix of past and present vernaculars and suggest...English spoken in Puritan 17th century Massachusetts” (Gottfried, 2003 p 224). “Miller’s accomplished use of the Puritans’ formal idiom suggests their rigid judgments of one another” (Rollyson, 1994 p 1681). The prose is gnarled, whorled in its gleaming as a stick of polished oak, an incomparable dramatic weapon” (Tynan, 1961 p 254). “The Crucible is built on a rhythm of assertion and denial, statement and retraction. Hence, Mary Warren is first accuser, then confesses the truth and then retracts her confession. The Reverend Hale is at first a fierce prosecutor and then a desperate defender. Elizabeth Proctor at first privately insists on her husband’s moral culpability and then publicly asserts his probity; Giles first accuses his wife and then retracts; Proctor first signs the confession and then tears it up” (Bigsby, 1984 p 198). “Hale is so fearful of being perceived as less than religious that he hides behind his books more than asserting without hesitation what he truly believes. Danforth is so fearful of being perceived as less than vindictive toward the accused that he hides behind his robes more than demanding substantive proof from the accusers. Putnam is so fearful of being perceived as less than prosperous that he schemes to steal what is not his. Elizabeth is so fearful of passion that she hides behind her judgmental frigidity while demurely maintaining that she cannot judge, which simply means that she cannot love. It's really her fear of loving that ‘would freeze beer’. The Crucible is a play that dramatizes manifestations of fear that arise when humans lose their way because they have lost each other” (Livesay, 2012 p 12). “The Puritans who initially provided the predominant temper of America, a temper that survives to this day, established the principle of economic and religious democracy. But the proper atmosphere for political dissent (so striking in England) and for moral freedom (for which America has alternatively envied and condemned France) was missing at the outset” (Goldstone, 1969 p 19). “The figures of authority in the play, including the reverend, the judge of the makeshift court and the authority on witchcraft, all work to suppress and maintain Salem’s theocracy” (Robinson, 2018 p 194). “The vested interests of the Puritan theocracy and magistracy are represented...by resentful, twisted, or narrow-minded souls: the contentious Parris...Reverend Hale...whose manly efforts to bring moderation...are thwarted with his own vacillating...gullible Governor Danforth...fumbling in his conduct of a special court, Judge William Hathorne, worried by problems of conscience and the Puritan suppression of all opposition” (Herron, 1969 p 34). “By contrast with those who too readily compromise and by parallel with Rebecca Nurse, who refuses to do so, Proctor becomes one of thee few who survive the crucible, though he loses his life doing so” (Schlueter and Flanagan, 1987 p 69). "Proctor refuses to yield to those who would hold him guilty of trafficking with the devil. And though he signs a confession on his dying day, and later retracts it, he refuses to name names and, finally, champions as his highest value the honor of his name. By contrast, others in the community who are accused are persuaded that confession offers the only hope of redemption, and each in turn both admits complicity and names others" (Schlueter, 2000, p 303). "Abigail is driven by revenge on Proctor and fear of being punished for dancing. To reach her goals, she is willing to have people of her town slain and 'subvert the function of the law'..."The Putnams are motivated by greed, Parris and Cheever by power. Danforth is eventually faced with a dilemma. Twelve people have been hanged...pardon for the rest would be to admit judicial error, and so he sacrifices them for the greater good, for rebellion is stirring in a neighboring town and chaos threatening the theocracy" (Porter, 1969 pp 188-195). “The Crucible rises to its heights on the personal level in Proctor's tragic predicament, but...the social and the personal are tightly interwoven...Miller had used Ibsen’s method of piecemeal revelation, gradually filling in details from the past throughout the play” (Gascoigne, 1970 pp 179-180). “The best versions of The Crucible don't divide its characters into a heroic Us, with whom the audience identifies, and an evil Them. We have to feel that we are all, potentially, one of Them. Every one of Miller's plays is steeped in a sense of guilt that taints each of its characters; they all take place ‘after the fall’. Proctor knows, to his agony, that his one act of conjugal infidelity has played a role in inspiring the horrors that overtake Salem. And just before his execution, he considers recanting, to save his life…In my ideal Crucible, the audience doesn't leave the theater identifying exclusively with Proctor. There has to be some part of us that knows that we, in such circumstances, we might just as easily have been Parris or Abigail or even a hypothetical Proctor who, at the last minute, chose another, safer road in the woods” (Brantley, 2012 pp 2-3). “John Proctor is a perfect character because he knows that he is imperfect. And that is our attraction to him, that he goes to his hanging with all his imperfections on his head. In the course of the play, Proctor comes to understand that it is possible to live without being perfect, that is possible to sin and still have goodness. His redemption lies at the tightening of the noose and the snap of the rope” (Marino, 2012 p 13). “Unlike Joe Keller and Willy Loman, Proctor ultimately is concerned with more than merely his own dignity. He dies defending not only himself but also the dignity of all the other innocent victims of the Puritan court’s brutal hypocrisy. This gives his tragedy a broader dimension than the downfalls of the heroes of Miller’s earlier plays” (Marino, 2018 p 94). “An engine of righteousness propels The Crucible and its powerful declamation against the ignorance that begets, allows and sustains political evil (Gottfried, 2003 p 225). “It is interesting to remember that 20 years after the executions, the government recognized that a miscarriage of justice had been done and gave compensation to the victims still alive...[To be] admired most is the sweep of Miller’s convictions, the power of his faith and the urgency of the subject matter” (Lumley, 1967 p 195).

"Death of a salesman"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1940s. Place: USA.

Text at https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.86608 https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.505675 https://archive.org/details/twentyfivemodern001705mbp http://www.pelister.org/literature/ArthurMiller

After a disappointing business trip as a traveling salesman and feeling old, Willy Loman returns home where his wife, Linda, proposes that he should ask his boss to work locally. He agrees he should. Despite showing early signs of promise, their sons, Biff and Happy, have yet to succeed financially, in Willy's view of utmost importance. In turn, the sons are worried about their father's mental condition. He often mutters to himself and shows signs of possible thoughts of suicide. When Willy accuses his sons of shiftlessness, they inform him that Biff is about to obtain a lucrative business proposition. Not only is Willy unable to convince his boss of working at the home office but he also loses his job, all this at the hands of the son of the man who first hired him over thirty years ago. Meanwhile, Biff is unable to get a job offer from a supposed friend. In frustration, he steals the man's expensive fountain pen. Willy meets Bernard, Biff's childhood friend, who tells him that Biff was never the same after going to Boston in his youth. Willy knows why. It was there that his disillusioned son saw him in the company of an unknown woman at a hotel. After a trying day, Willy meets his sons at a restaurant to hear news and perhaps celebrate. Unwilling to hear of any sort of bad news concerning Biff, the brothers feel constrained to lie about Biff's success. While Willy washes up in the restaurant washroom, Biff suddenly leaves, so does his brother to pursue the alluring company of two unknown women. Angry and aggrieved at learning about her sons' behavior in the restaurant, Linda accuses her sons of heartlessness. When a frustrated Willy learns the truth about Biff's rejection, he accuses him of failing out of spite. Biff angrily shows him the electric cable Willy used in attempting suicide awhile ago, asking him whether that was meant to inspire pity for him. Willy pretends to know nothing about it. Biff divulges he was imprisoned for a few months for theft and lost other jobs because of it, a result of being unable to take orders from anybody because of his father's tendency to exaggerate his importance. "I'm a dime-a-dozen, and so are you," he shouts. "I'm Willy Loman and you're Biff Loman," Willy retorts, still believing that since he is a Loman, he must necessarily succeed. Conscious of his worsening mental condition, he nevertheless drives away and incurs a fatal road accident, a suicidal sacrifice to his family's welfare. At the funeral, Biff refuses to take the life insurance money so start a business career, but Happy decides he will follow his father's wishes.

"The crucible"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1690s. Place: Salem, Massachusetts.

Text at https://archive.org/details/TheCrucible https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.505675 https://pdfcoffee.com/the-crucible-pdf-free.html

Reverend Parris' daughter, Betty, lies in bed unresponsive after he caught her dancing in the forest with her friends. She fears punishment while he fears his enemies will use this incident to bring him down if the girls called forth spirits. He questions Abigail, his niece, about this event, who admits only to dancing. But Thomas and Ann Putman are convinced there is witchery about, because their daughter, Ruth, is afflicted with the same condition as Betty. "It's death, y'know, it's death drivin' into them, forked and hoofed," Ann declares. She is convinced a black slave, Tituba, conversed with the dead to find out who murdered her seven babies who died at childbirth. Reverend Hale arrives from out of town to investigate the rumors of witchcraft. Abigail seizes this opportunity to accuse Tituba of conjuring. In the ongoing investigation, Giles Corey reveals that his wife reads books at night. "I'm not sayin she's touched the devil, now, but I'll admire to know what books she reads and why she hides them," he declares. The deeper the investigation probes into, the higher the number of suspects increases. John and Elizabeth Proctor learn from their servant, Mary, that 34 women have been arrested and at least one man, Osburn, is condemned to hang, accused by his servant, who had been turned away empty while begging for bread. For disobediently leaving the house, John raises his hand to whip Mary. To protect herself, she cries out that she saved his wife from suspicion after being accused by Abigail, their former servant, because, according to Elizabeth, Abigail desires to take her place as John's wife. More officials arrive and Elizabeth is charged with witchcraft after all, because a doll was found in her possession with a needle in it, after Abigail had been stuck that very night with a needle in her belly. In the Salem court-house, Corey pleads his case before Deputy Governor Danforth, defending his wife accused of witchcraft, far from his original intentions, for he only wanted to find the cause why his wife reads books. Corey, John, and Francis Nurse, all three men whose wives are charged with witchcraft, accuse on the basis of Mary's confession Abigail, Betty, Ruth, and others of fraud. Afraid of what may happen to his daughter and himself, Parris immediately disbelieves it. Although Hale, having signed 72 death-warrants, nervously wishes this accusation to be seriously examined, Danforth resists, so that Mary's version is disbelieved. When Danforth examines Elizabeth's case, the Proctors contradict themselves, he admitting to have copulated with Abigail, she, to defend his name, swearing he did not. As a result, she is condemned to die. A cornered Mary now points to John as "the devil's man" and joins her friends in crying out further accusations. Later, Danforth is deeply troubled on learning that Abigail and Mercy Lewis robbed Parris and escaped from the area in a ship. Twelve witches have already been hanged, partly on the basis on their accusations, yet he decides to continue the examinations. Since Elizabeth is pregnant, her condemnation is delayed. She begs her husband to admit he used witchcraft, but he refuses and is hanged.

William Inge

[edit | edit source]

In addition to Miller, indirect social commentary is prominent in the plays of William Inge (1913-1973), notably "The dark at the top of the stairs" (1957). Inge also wrote "Come back, little Sheba" (1950) and "Picnic" (1953). The former "revealed insight into commonplace life and a capacity for transfiguring it into consuming pathos. The play dealt with a well-bred man’s sense of failure in marriage and his explosive alcoholism before he relapses into remorseful quiescence" (Gassner, 1954a p 740).

"The dark at the top of the stairs" “lets a young family find its way through a variety of emotional crises, triumphing over none but surviving all, through admission of mutual dependence” (Berkowitz, 1997 p 183). “The divided emphasis of the play, [the Rubin-Cora conflict and Sammy’s suicide] was disconcerting and distracting to some critics...Sammy’s suicide brings Cora and Reenie to a new understanding of what life is about and to a deeper understanding of themselves. Certainly the suicide is the major precipitating factor in Cora and Rubin’s being reunited...Rubin...is afraid of the dark, because it represents the uncertain future that stretches before him. But just as Cora assuages Sonny’s fear of the dark by going up the stairs with him at the end of act 2, so does she assuage Rubin’s fear of the dark future by going upstairs...at the third-act curtain...Rubin leaves Cora because he does not want to be like his hen-pecked brother-in-law, Morris. When he returns to her, it is apparent that he will be tamed in much the same way Morris has been. A night in bed will neither alter the overall futility of the Floods’ marriage nor resolve the problems responsible for Rubin’s insecurities...Even at the end of the play, Rubin is unable to communicate with his son...Reenie is not unlike Laura Wingfield in Williams' Glass Menagerie (1945)...Reenie’s shyness is indirectly responsible for Sammy’s suicide...[Afterwards], for the first time, Reenie uses her music not as a form of escape for herself but as a means of bringing pleasure to someone else...Sammy dominates the first half of act 3 even though he is dead” (Shuman, 1989 pp 53-63).

“All of the family’s fears, of isolation, connection, poverty and loss of respect, are manageable by the close of the play, as Cora mounts those stairs toward her husband, and her children happily attend a movie together. Through love and honesty, the family have reconnected in more positive ways, and it is those outside this group, Lottie, Morris and Sammy, who end in darkness, as the shallowness of Lottie and Morris’s marriage has been revealed and Sammy commits suicide. Once they have relinquished their petty differences, the Flood’s household is based on love, and that has made all the difference…There are further aspects that make it a 1950s play, with several jokes and references to psychiatry, and Cora’s suggestion that kids don’t just get over things in some magic way. These troubles stay with kids sometimes, and affect their lives when they grow up. Also, Reenie’s schoolfriend Flirt’s comments on her differences of opinion with her father evoke the growing cultural generation gap of that decade…Reenie may be shy, but she is not ignorant. She knows that Flirt is just using her, and her qualms about going with Sammy are not because he is Jewish, but because she would be uncomfortable with anyone. While she understandably finds her petulant brother annoying, she is a sensitive soul and loves her family. She worries over the expense of the dress and when her parents fight. Both Reenie and Sonny keep the wider society at arm’s length, but while Reenie finds it intimidating, Sonny seems to find it simply repugnant, aside from his idealized film stars…Cora is more refined than her husband and from a moneyed background, but she loves him. Her love, however, can be smothering for all the family, as it manifests in a belittling jealousy toward her husband as she tries to bully him in the same way she bullies her children when she is not using her disempowering protectiveness against them. She envies her richer friends, which causes a rift in her marriage, but we are meant to excuse her for this as she was pampered as a child, her husband has not been fully honest with her and once he is she accepts the situation without complaint. She is also, despite her initial intolerance toward her own family, by the close, the greatest voice of tolerance in the play” (Abbotson, 2018b pp 120-122).

In the first act of "The dark at the top of the stairs", "a baseless quarrel between a husband and wife results in his departure. The tension arises from the husband's inability to communicate his anxieties to his wife and from the latter’s failure to realize how frightened of the future this superficially confident man is...The play, sometimes veering toward comedy and sometimes toward tragedy, was inconsistent in tone...The last scene of the play, the prodigal lummox beckoning his wife upstairs to bed while beckoning the kids out of the house, stuck me as forcibly and inharmoniously comic. I had little stomach for comedy after observing the suffering of the children and experiencing the penumbral mood of the scenes just past” (Gassner, 1960 p 171).

“It is in fact Cora's interest in the children, at the expense of her relationship with Rubin, which causes him to leave home. The precipitating argument over a party dress for Reenie, is only a manifestation of their far deeper marital problems, problems which are resolved by Cora's shattering of Sonny's attachment to her and by her sending the children to the movies so that she and Rubin can make love undisturbed. Also, by the end of the play, the children's rivalry has diminished, and one can assume that Sonny will also be able to overcome his jealousy toward his father. Reenie has always been closest to Rubin, and consequently her dislike of Sonny is based partly on the boy's undisguised glee at the prospect of his parents' permanent separation. Sonny is selfishly delighted that his rival has vanished and that as a result, he may get to live in a new town, away from the taunting boys of bis neighborhood. His sister, of course, feels quite the opposite...And Cora, in her fear and worry, turns not to the daughter who is older and probably more capable of understanding the dynamics of the situation, but to the child whose love is animal and total” (Mitchell, 1978 pp 302-303).

“Lottie...works defensively at being an extrovert, Morris Lacey, her sensitive husband, a dentist who has the resigned gravity of a meek and defeated man looking back on his bachelorhood...Sammy...a Jewish cadet...who has suffered from both prejudice and lack of parental care...are all afraid of the dark at the top of the stairs...a moving, perceptive, and striking drama of the impact of the changing times of the 20s upon southwestern townspeople” (Herron, 1969 pp 434-435). “Many critics see [Lottie] as a pathetic creature trapped in a childless marriage with her passionless husband...Her vulgarity, bigotry, and self-righteousness are the products of a protective persona, similar to Rosemary’s [in “Picnic” 1953], that she busies to shield herself from the essential angst of having to create an identity instead of allowing others to determine her character for her. Lottie presents one self to Cora, another to Morris, both mutually inconsistent. She acts more solicitous about the feelings of others than she does about her own shortcomings, allowing Cora to believe that he envies her wife-beating adulterous husband and her spoiled, irascible children, while remaining sensitive to Morris’ moods and keeping him in her confidence...[In the ending of the play], there is no sign of romantic epiphanies, only a salesman hawking a new and improved version of himself and a wife who will put up with beatings and infidelity for a steady squeeze and the semblance (at least) of paternal authority guaranteed to stabilize the household” (Johnson, 2005 pp 80-82). Brustein (1965) resented the wife’s man-taming: “Underneath Inge’s paen to domestic love lies a psychological substatement to the effect that marriage demands, in return for its emotional consolations, a sacrifice of the hero’s image (which is the American folk image) of maleness. He must give up his aggressiveness, his promiscuity, hid bravado, his contempt for soft virtues and his narcissistic pride in his body and attainments and admit that he is lost and needs help. The woman’s job is to convert these rebels into domestic animals. If this requires (as it always does with Inge) going to bed with the hero, she will endure it; and although she may accuse her husband...of marrying her because she was pregnant, she nevertheless has managed to establish the hero’s dependence on her and thus insured that he will remain to provide for the family” (p 90). Other critics view the ending more positively. "The loss of his job forces Rubin to acknowledge his weakness towards a wife he has neglected in a world where economic progress has left him behind and where the future and his place in it are unknown. The dark symbolizes, in part, that fear of the unknown. When Rubin stands naked at the top of the stairs...and beckons Cora to come, his nakedness suggests acceptance of his vulnerability; now unafraid to reveal his weakness as well as strength to Cora, he knows she will provide the reassurance of physical love to bolster his self-respect" (Adler, 2007 p 166).

“While Tennessee Williams continued to depict the miserable lives of non-conformists, Inge seemed to depict the equally miserable and lonely lives of conformists. Inge presented images of ordinary Americans who lived outside the main urban areas, and, through his portraits, challenged the old idealized image of small-town America by depicting such places as filled with frustration and limitation. His work centres on Midwesterners, never previously considered to be good subjects for art, but through them he draws out the difficulties of living and surviving in a country that promised much and often delivered so little” (Abbotson, 2018a p 50). "If there was a playwright who shared the respect of Miller and Williams in the fifties, not for innovation of form but for the sensitivity with which he dramatized the American family, it was William Inge...In this important cluster of plays, which had respectable runs on Broadway, Inge examines a large but typical cast of characters and relationships, repeatedly creating situations that dramatize the details of lives anesthetized by habit, dreams suffocated by compromise, and sexuality denied- the stuff of small-town America" (Schlueter, 2000 p 307). “Inge’s strongest depictions are of female characters, particularly sexually frustrated ones who have little control over their own destinies. If they controlled and sometimes emasculated their men, as Robert Brustein (1958) contended, they did so because their men needed taming. Jhunke’s (1986) objects to this portrayal on the grounds that many raucous men settle down when they attach themselves to one woman” (Shuman, 1989 pp 147-148).

"The dark at the top of the stairs"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1920s. Place: Oklahoma, USA.

Text at https://pdfcoffee.com/qdownload/dark-at-the-top-of-the-stairs-inge-pdf-free.html

Before going to work as a traveling salesman, Rubin discovers that his wife, Cora, bought their daughter, Reenie, a party dress he considers too expensive. Husband and wife quarrel. He hits her and threatens never to come back. She considers moving in with her sister, Lottie, but the latter thinks that solution is impractical. Lottie has her own troubles, including the troubling fact of her not making love with her husband, Morris, for over three years, though admitting that this state is partly her fault. "I never did enjoy it as some women say they do," she admits. Renee is so anxious about going on a blind date with a stranger, Sammy, that she vomits at the thought. Because her mother is a movie actress, Sammy has been living in military academies throughout his life. He is very friendly with Renee's brother, Sonny, as they head to a party given by the rich Ralston family. On their way out, Cora asks her son to walk upstairs, but he is afraid of the dark, though not when someone accompagnies him. The next day, Reenie lies to her mother over the fact that she left the party because Sammy went off to court other girls. When asked whether she would have done as others do, she responds that Sammy "would not have liked me that way". "I'm just not hot stuff like the other girls," she adds. Sonny bursts into the room excitedly to announce that he won $5 for reciting at a tea-party. When his mother places the money in his piggy bank, he is offended and says he hates her. The family is stunned on learning that Sammy committed suicide. Cora insists that her daughter tell her what really happened. Reenie danced three straight times with Sammy until she was ashamed of having no other boy ask her. "I just couldn't bear for Sammy to think that no one liked me," she confesses. She introduced him to the daughter of the house, but Mrs Ralston interrupted their conversation, exclaiming that she will tolerate no Jew dancing with her daughter. Rubin returns home to say he lost his job. He is sorry for having struck his wife, but becomes impatient again when she strongly suggests a position he may apply for in town instead of traveling. Nevertheless, they become reconciled. With a view of going to bed with his wife, Rubin gives his son money to go to the movies. Ashamed at the selfish way he has treated her, Sammy smashes his piggy bank to treat his sister to the movies. With her husband waiting for her at the top of the stairs, Cora ascends slowly, as if she were the shy maiden she once was.

Sam Shepard

[edit | edit source]

Sam Shepard (1943-2017) achieved prominence with "Curse of the starving class" (1977), "Buried child" (1978), "Fool for love" (1983), and “A lie of the mind” (1985).