History of Western Theatre: 17th Century to Now/Baroque

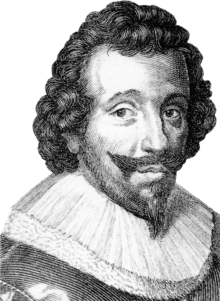

Pierre Corneille

[edit | edit source]

The main tragedian of the French Baroque period, approximately from 1601 to 1643, the year of the death of King Louis XIII, is Pierre Corneille (1606-1684), whose main plays are "Le Cid" (The Cid, 1637), "Horace" (1639, rewritten in 1660), "Cinna" (1640), and "Polyeuctus" (1641). The plays of Pierre Corneille (1606-1684) extend from the Baroque to the Classical (or Neoclassical) period (approximately 1644 to the end of the century), from "Melitus" (1629) to "Surena" (1674).

The plot of "The Cid" is taken from a play written by Guillen de Castro (1569-1631). “The underlying motives are in Castro’s play; and of all the important scenes in the Cid, the second interview of the lovers Is the only one which has no prototype in the original Spanish play. But it was Corneille who centered the interest on the psychological problem by making the events of secondary importance. From one point of view, this change in tone was an easy one to make. The observance of the non-essential rule of the unity of time had great influence on the dramatist in making this change; but the result was none the less a masterpiece” (Stuart, 1960 p 397). “Under cover of the customary interpretations of Horace’s remarks on the mixing of the useful and pleasant, and of Aristotle’s on the subject of probability, the [French] Academy delivers a fierce attack on the immoral conclusion of the play. It maintains that propriety is outraged by a virtuous lady marrying the slayer of her father, and that probability is violated by Don Fernand’s unjust order that the marriage shall take place. Unconsciously damning the rules, it admits that Chimène’s passion for Rodrigue is the principal theme of the play and that its presentation is admirably and convincingly wrought, but asserts that this ought not to please, and that it pleases only those who are ignorant of the rules (of probability). It admires the poet’s choice in depicting a conflict between love and honour, but insists that a greater beauty as well as more probability would have been secured had Chimène’s honour triumphed over her love, and the lovers remained forever apart. But if honour yielding to love had to be portrayed, it suggests that it would have been better to have depicted Rodrigue’s refusal to avenge his insulted father than Chimène’s eventual consent to marry Rodrigue. It is curious that the Academy should be chiefly impressed with the unnatural conduct of Chimène, for what strikes the unbiased reader is just the opposite; she seems over-solicitous of her honour, and persists in regarding Rodrigue as her foe even though her father had been the aggressor in the quarrel scene, though Rodrigue had saved the state by his victory over the Moors, though chivalry required her to marry the victor of the duel which was fought to satisfy her vengeance, and though the king had commanded the marriage” (Deane, 1931 pp 67-68). "The double strife between love and duty was depicted with matchless force and sympathy; the haughty spirit of the great vassals of medieval Spain shone forth in all its energy; imaginative power, vivid portraiture of character, glowing energy of thought and expression- nothing seemed wanting" (Hawkins, 1884 vol 1 p 101). “Both [lovers] recognize that their sense of personal worth can only be confirmed in action within the order which surrounds them and that their love must be expressed in fidelity to their participation in that order. But this recognition brings with it a bitter paradox, since they can only give practical expression of their feelings for each other through a code of honour which accords so little importance to love that it sets at risk any hope of union...Both come to see that by upholding the point of honour they do not destroy their love, but find the only way to sustain it at its most elevated level...Jimena...makes it clear that love itself defines her future course of action rather than the violent ethos of the point of honour. By setting aside the sword which Rodrigo presses upon her, she rejects the partiality of a code in which the avenger is plaintiff, judge, and executioner...in appealing to the crown...By pardoning Rodrigo, [the king] has undoubtedly served the general interest, but he has also laid himself open to the reproach that his decision is tainted with an opportunism which makes short shrift of the individual rights...he has sworn to protect” (Clarke, 1992 pp 149-156). "Jimena's pertinacity in demanding the death of Rodrigue is altogether the result of reflection; whatever grief she may have felt at the death of her father, it is not grief which hurries her to the feet of the king, but the idea of what she is bound by honor to do. But the feeling which possesses her continually diverts her attention from the idea which governs her; at the same time that she does what she thinks duty commands for her father, she says what she feels for her lover, and The Cid, the only one of Corneille's tragedies in which love ventures to display all its power, is also the only one in which he has followed the natural rule of giving action to character and words to passion" (Guizot, 1952 p 208). “Whereas Rodrigo has nothing to hide in his quest for glory, both Jimena and the infanta feel it necessary to disguise their love for him in public...The heroines subscribe to the same ethic as the male characters, but society makes it much more difficult for them to uphold it...Rodrigo is defeated just as Jimena is by the admission of love...the moment of anagnorisis as Aristotle defined it, the act of recognition that reverses the direction of plot lines...[But Rodrigo comes out more victorious in his unhappiness in being able to avenge his father and become recognized as] society’s savior” (Carlin, 1998 pp 54-57). “The nobility of the young lovers, their steadfast adherence to what they conceive to be their duty, and the greatness of their love for each other...have always captured and will always capture the hearts of people everywhere...Its chief defect is, obviously, the role of the infanta...though the disingenuousness of her advice to Jimena at times and the uncertainty of how she may intervene in the course of the events...increase in some small degree the tension of the tragic predicament...Wonderful [in the scenes between the lovers] is their emotional power- the beauty and vital force of the eloquent depiction...of the heart’s true feelings bursting into irrepressible utterance” (Lockert, 1958 pp 29-32). Other critics find the infanta'a role limited but not a defect. “The [infanta’s] role constitutes a dramatic as well as a lyrical echo of the main plot. It is a sort of play-within-a-play functioning as a ‘mirror’” (Nelson, 1963 p 84). "Corneille was in the best way of the world when be brought his Cid on the stage, a story of the middle ages, which belonged to a kindred people, characterized by chivalrous love and honour, and in which the principal characters arc not even of princely rank. Had this example been followed, a number of prejudices respecting the tragic Ceremonial would have disappeared of themselves; tragedy from its greater verisimilitude, and being most readily intelligible, and deriving its motives from still current modes of thinking and acting, would have come more homo to the heart: the very nature of the subjects would alone have turned them from the stiff observation of the rules of the ancients, which they did not understand, as indeed Corneille never deviated so far from these rules as, in the train, no doubt, of his Spanish model, he does in this very piece; in one word, the branch tragedy would have become national and truly romantic. But I know not what malignant star was in the ascendant: notwithstanding the extraordinary success of his Cid, Corneille did not go one step further, and the attempt which he made found no imitators" (Schlegel, 1846 p 263).

In "Horace", while "dealing with the heart-struggles incident to the combat between the Horatii and the Curiatii, the dramatist displayed a power beyond that of the Cid, besides demonstrating his ability to construct a plot with the simplest materials. Especially impressive is the figure of the elder Horace...He seems to concentrate in his person the whole grandeur of the Roman character. His love for his children, deep-rooted as it is, at once yields to his patriotism" (Hawkins, 1884 vol 1 p 121). "Old Horace, when he believes that his son has fled, forgets his paternal love, and desires, nay more, almost commands, the death of his son; but love of his country, the obligations imposed upon his family by the confidence of his fellow-citizens, the criminality of the coward who had betrayed that confidence, and even the advantage of his son, for whom death would be a thousand times more preferable than an infamous life- all these are feelings so powerful, and of so exalted an order, that we are not surprised to see that they gain the victory over even paternal love, the well-known force of which only adds to the admiration inspired by the superior force which has conquered it" (Guizot, 1952 pp 219-220). In "the character of the elder Horace, we are presented with a type of the antique Roman as tradition and fable had depicted him stern, implacable, an ardent lover of his country, and ready to sacrifice all for her welfare. When the choice of Rome falls on his three sons he restrains all natural tears, and exhorts his daughter-in-law Sabina to do likewise. News having been brought him that two of his sons are slain and that the third is fleeing before the Curiatii, his wrath and indignation know no bounds, and he threatens to slay him with his own hands should he escape" (Hallard, 1895 p 31). "Extremely impressive was the figure of the father of the Horatii, as acted by Bellerose, who seemed to concentrate in himself all the grandeur of the Roman character. Intensely pathetic is the struggle between love for his children and the feeling of patriotism to which it yields, and not less so the parting from his son and the affianced lover of his daughter, who were soon to meet in deadly strife. But the master-stroke was in the scene where, after cursing the son who had fled, as he thought, when his brothers were slain at the first encounter, the father is asked: 'What would you have him do against three?' 'That he die,' he answers" (Bates, 1903 vol 7 French drama p 64). “That a character should undergo change in the course of the play is universally regarded as one of the finest achievements of dramatic art...It occurs in 'Horace’...[At first], Horace is proud of the distinction accorded him but modest withal...When Curiace is overwhelmed on learning that he and his brothers are meant to fight...Horace tries to help him...[but] something of strain and excess is already evident...When Curiace protests...he becomes contemptuous and arrogant...but...he comes home triumphant...without comprehension or toleration of Camilla’s anguish. And when finally he is tried for killing her, he is quite devoid of any sense of having disgraced himself by this brutal crime...To have become the man he is in the last two acts is assuredly tragic and that he became such a man as a result of having answered his country’s call in the best of all possible ways may well excite in us both pity and terror” (Lockert, 1958 pp 40-42). In the view of Symons (1979), "Sabina- a character of love and compassion- is the most sympathetic and least admirable character of the play and Horace- a character of honor and absolutism- is the least sympathetic" (p 100). “Horace’s flight might not have been part of a larger coherent plan but instead simply an unpremeditated escape from certain death, an escape that serendipitously evolved into an upset victory” (Lyons, 1996 pp 45-46). If the act was non-premediated, Horace’s murder of his sister becomes yet another impulsive deed. “In seeking private justice for her lover, Camille parallels Horace in his seeking private justice for her verbal affront. Together, the two siblings are representative of an archaic moment in Roman history in which the family could dispense its own justice and co-exist with other self-regulating families or clans...Camille’s hatred of Rome belongs to a period in which an individual or a family could choose between Rome and other peoples...When Valerius attacks and Horace the Elder defends Horace, they are arguing about the effective limits of the family structure...Horace the Elder is upholding a family-centered view of law and justice against a generalized Roman dispensed by the king as requested by Valerius” (Lyons, 1996 pp 55-61). The ending of the play flies against Aristotelian principles, because Horace “learns no tragic lesson...he retains the values with which he began...[In contrast], tragic presentiments are realized in Sabina’s case. In her, we find a character who runs into irreconcilables: she must yearn for the victory of her brother only at the expense of the loss of her husband; she must yearn for the victory of her husband at the expense of the loss of her brother. She loses the brother: private value is sacrificed to public value” (Nelson, 1963 pp 93-94). Horace's "barbarous yet necessary act reveals his strength of will. As a Roman conscious of Rome’s destiny, Horace believes that his act is patriotic and religious” (Corum, 1986a p 432). “Roman patriots appear ambitiously insensitive to the promptings of common humanity. Julie’s advice to Camille that she should regard her lover as no more than an enemy also shows how small a place the bonds of love play in Rome’s march to future glory. In contrast...the Albans are [sensitive] to the ties of love and nature...Sabina tellingly returns to the theme of a sister’s suffering for her Alban brothers...Ever the rigorist in the exercise of Roman justice, Horace at once offers his life in submission to the paternal authority he had usurped in killing Camille. But his father, as Tullus will later do at the level of the state, flinches from the Roman logic of his son’s argument and cannot bring himself to kill him, preferring instead a shared guilt in dissimulation of past criminal action [as] he recoils from yet another sacrifice of natural bonds to the communal good...When Horace has trusted that the king in his wisdom would comprehend his conduct, Tullus refuses his plea that he be allowed to die and instead condemns and pardons him for a crime of which the hero knows himself to be innocent” (Clarke, 1992 pp 180-194). “Tullus incarnates the state...dispensing a brand of justice acceptable to all...Camille receives her due as...she will be entombed with Curiace, [which] shows the value of what has been excluded” (Carlin, 1998 p 61).

"Cinna" is based on the life of Gnaeus Cornelius Cinna Magnus (born between 47 and 35 BC). "Based upon a page of Seneca the Younger (54 BC-65 AD), "On clemency" (55 BC), but original in regard to many incidents and figures, it exhibited a majesty of thought and language for which 'Horace' itself had not prepared the town. Especially striking was the opening of the second act, where Cinna urges Auguste to restore the liberties of Rome, and Maxime seeks to impress the emperor with a sense of the danger of abdication...Finding that Cinna, whom he has educated with paternal care, is engaged in a conspiracy against his life, Auguste...summons him to his presence, reminds him of his obligations, shows that the plot has been discovered, and...when spectators unacquainted with Roman history were trembling for the fate of the culprit, says 'I am the master of myself as well as that of the universe'...This magnanimous clemency, free from any suggestion of the prudential motives by which the Augustus of history was actuated in the matter, created a profound impression" (Hawkins, 1884 vol 1 pp 125-126). “Augustus’ clemency robs the play of its tragic potential...Augustus senses that in the satisfaction of one legitimate desire (and the will to power is legitimate in Corneille) we find the frustration of another which is equally legitimate: the desire for security...The Augustus of ‘Cinna’ is an atypical Cornelian hero. Power and peace of mind are no more at odds with one another in Rodrigo than they are in Horace. Nor are they ultimately in Augustus” (Nelson, 1963 p 98). After Augustus consults Cinna and Maximus as to whether he should step down as ruler, he decides to stay, giving Cinna Emilia’s hand in marriage, trusting all three conspirators, and thus gives a pathetic aura to his role...’Cinna’ is a play about recognition, about finally being able to recognize the exceptional qualities of leadership that will save society from the confused circle of exchanges and reversals in which it is mired” (Carlin, 1998 pp 63-65). “Emilia opens with the great themes of personal vengeance and tyrannicide but concludes in wholehearted acceptance of her natural place within a renewed social order, breaking free of personal hatred in a personal endorsement of monarchial authority...As soon as Augustus appears in Act 2, however, we are confronted with a troubled but generous-hearted ruler who is clearly not the despot for whom we have been prepared...Events inexorably reveal the gap between Cinna’s public claims to embody a principle of divine justice and his personal reluctance to pursue a line of conduct which draws him even further into the secret shames of deceit and ingratitude towards a ruler who does not act like a tyrant legitimately to be overthrown...Augustus belies the conventional assertion that a tyrant’s cruelty is matched only by his mistrust of others” (Clarke, 1992 pp 206-214). “When [Augustus] first learns of the conspiracy, his reflections leave him undecided...In the fifth act, there is no hint of leniency...He tells [Cinna] to choose his own punishment...then the horrified emperor discovers that Emilia, too, has conspired against his life, yet he still had no thought of mercy...then Maximus appears...and forthwith [he] pardons them all...That change...can only be the result of his realization that all his previous severity has left him no one whom he can trust...[Regarding Emilia, one wonders whether it is] humanly possible that after hating Augustus so bitterly for so many years, she could in a twinkling reverse her feelings” (Lockert, 1958 pp 47-48). “In the most conflictual of plays, we witness Corneille’s audacious redefinition of tragedy and the tragic. Cinna presents an insidiously clever articulation of a new tragic vortex. It is a vortex of rhetorical illusion which draws into its own center, in ever descending ‘spirals of power and pleasure’, the diverse demands of sexuality and politics. It produces a violence so great, yet so subtle, mutilation so total, that death can be omitted without in any way diminishing the shattering effect the play exercises on its audience. In Cinna Cornellian tragedy truly becomes ‘cosa mentale’. By not giving in to his thirst for revenge, Auguste, who had up to now only been the ‘master of bodies’, becomes the ‘master of hearts’. He breaks out of a system of repetition that had condemned Rome to constantly replay her internal strife in dissension and fragmentation and thus constitutes a new order of history where because of his generosity his erstwhile plotters become his most devoted allies; instead of a renewal of Republican zeal, all is now sacrificed to the glory of the monarch” (Greenburg, 2020 p 9).

"Polyeuctus" is based on the life of the 3rd century saint of the same name. "In the characterization of the personages, it is to be noticed that both Polyeucte and Pauline feel the full force of emotion, and the tragic conflict is real, and ends in the domination of the natural by the spiritual man. Thus the great scene between Severe and Pauline in the second act is imposing from the strength of Pauline's attitude. Reason and the obedience due to her father have overcome her passion for Severe, but Severe's reproaches to her as cold and inconstant bring out, first, her consciousness of an inner struggle (reason is the tyrant in her mind over rebellious and all but unconquerable feelings) and secondly her sense that only by obeying what she takes to be her duty, she can be worthy of Severe. Of the main action, then, it may be said that it is a fair and complete type of Corneille's dramatic work. The struggle in Polyeucte's mind is communicated to Pauline, to Felix, to Severe, and reverberates in this way among the characters on the stage. The dramatic characterization is responsible for the variety of ways in which the struggle is felt. With both Polyeucte and Pauline, though Polyeucte is in advance, the issue is practically certain, but Felix's change of heart comes as a rebound after his meanness and cruelty. Severe, naturally generous, represents the better Pagan ideal, but cannot at the beginning of the play be counted upon to act on the same high plane as the Christian Polyeucte. Pauline's action, self-controlled and rational to an ideal pitch, is made more natural by the expression of a strongly developed intuitive side to her character, and this makes it clear that the conquest over fear, irresolution, and emotion is no easy and mechanical thing to her. Her character shows a mental and spiritual force bridling a strong temperament, and the last scenes are lighted up by the brilliant enthusiasm that can be shown in such a nature" (Jourdain, 1912 pp 57-58). "Polyeucte, Sévère, Félix,and Pauline are drawn with a masterly hand. The spiritual progress of both Polyeucte and Pauline is carefully indicated. The ending, with the opportune conversion of the wily politician, may be defended as a final tribute to the power of grace. The play is written in a simple unaffected style, with varied scenes, careful analysis of motives, perfect unity of structure and harmony of tone” (Lancaster, 1942 p 62). “As the governor of Arménie, he represents the power and authority of the Roman emperor Décie. His primary characteristics are ambition, fear, and egotism. Félix married his daughter to Polyeucte to further his own career; he fears the newly powerful Sévère whose courtship of his daughter he rejected earlier; he puts the newly-converted Polyeucte to death because of that fear. Indeed, Félix interprets everything in reference to himself, and thus frequently misreads the behavior and attitudes of those around him. He is a poor father, willing to sacrifice his daughter for his own ends and completely insensitive to her feelings. Despite a scene of internal conflict (III.v) and occasional feelings of shame or affection, Félix seems to belong to another world than that of Polyeucte, Pauline, and Sévère. He shares none of their heroism and nobility of character…Félix’ conversion in the final scene of the play, an act through which he moves to unite himself with Polyeucte, Pauline, and Sévère, and through which Corneille seeks to end the play on a note of transcendence, raises significant concerns. This conversion is an invention of Corneille and is not found in the source material…One of the hallmarks of Corneille’s dramaturgy is a fondness for surprise…From a religious perspective, the conversion of Félix, like that of Polyeucte and Pauline, is explained by grace…Corneille, whose every play is testimo- ny to his belief in free will, has two of his characters in Polyeucte, Pauline and Félix, undergo a conversion that entails no reflection or consent whatsoever…It is a convention of seventeenth-century tragedy that all characters must be accounted for in some fashion before the play may end… Thus, Félix’s conversion allows the play to end in keeping with the norms of the classical theater. On the other hand, his transformation presents the disadvantage of creating a sense of clutter in the denouement and significantly distracting from Pauline’s conversion”...Pauline’s conversion is very successful: it combines strict causality (Pauline’s contact with blood engenders her immediate transformation) with emotional appeal (Polyeucte shows his love for his wife in death). The case of Sévère is more mixed. His non-conversion makes some sense dramatically, as it provides someone to protect the newly Christian Pauline and Félix, as well as to convince Décie to halt persecution of the Christians…Félix’s conversion, while arguably plausible from a religious perspective, is completely implausible logically, psychologically, and dramatically...I would like to suggest focusing on a distinctly different element as a key to understanding Félix and his conversion: the theatrical...It is entirely plausible that faced with consequences worse than those posed by a Christian son-in-law, Félix would take any steps necessary to pacify Sévère. Specifically, Félix would realize that the only way to appease the young man is through Pauline, who herself would be touched by nothing less than a paternal conversion to echo her own. Becoming a Christian would even efface his crime of persecuting the sect and notably of having put Polyeucte to death. Indeed, whether a stratagem or not, Félix’s conversion works perfectly. Interestingly, Pauline and Sévère are more likely to accept his transformation at face value than is the spectator because they were not witnesses to the scene in which Félix pretended interest in Christianity to Polyeucte (V.ii). Corneille even embeds a few hints in support of a theatrical interpretation. First, Sévère, witnessing Pauline’s joy at her father’s conversion, exclaims: ‘Who would not be moved by such a tender spectacle?’ (l.1787). The choice of the word ‘spectacle’ conveys the theatrical potential of the moment. He also confirms the line of reasoning I am positing here: “If you are Christian, no longer fear my hatred,’ (l.1800)…More conventional in terms of the language of conversion, but still subject to an ironic double reading, is the line: ‘I yield to transports I do not know’ (l.1770). As in the case of [Rotrou’s] Genest, once a character is associated with acting- as Félix is in V.ii- it becomes impossible for that character to disassociate himself from role-playing in the eyes of the spectator. I believe that Félix’ ties to theatricality, placed judiciously throughout the play, are the basis for the widespread discomfort with Félix’ conversion and authorize the non-standard interpretation we are suggesting here” (Ekstein, 2012 pp 3-13). Opposite views have been presented as to the character of the main character. "'Polyeucte' is based upon the life of an early Christian martyr, and the two ideals, of Christian sacrifice and of chivalric honor, which are commingled in it, are incapable of perfect fusion, for the basis of the former is humility, and of the latter pride" (Harper, 1901 p 64). “Heroism and sainthood blend without conflict in ‘Polyeuctus’...rare among Christian saints” (Carlin, 1998 p 70). “Tenderness of feeling and human sympathy are pitted against Christianity in the character of Polyeuctus, [in whom] we seem to come to an absolute transcendence of worldly things as means of defining one’s integrity...In seeking his own death, Polyeuctus is racing toward a still more exalted conception of himself...Pauline...uses Severus in an unsuccessful effort to provoke jealousy, but Polyeuctus is too much in control of himself and too preoccupied with his real concern to take this bait...The limited perspective of other human beings is his antagonist, and he would overcome that perspective in a supreme act of self-affirmation...The problem of his wife’s happiness can be all the more easily settled by his commitment of her into Severus’ hand” (Nelson, 1963 pp 101-106). "The conversion of Pauline and Felix reassures us that Polyeuctus has not acted in boldest zeal only for his own salvation...The very image of the fading qualities of a pagan world in decline, Severus illustrates a ‘reason’ more concerned with the status quo and social harmony than with metaphysical certainties. His urbanity may set him apart from Decius’ monstrous despotism, but it also leaves him blind to the future and unilluminated by the sacrificial devotion of the hero of the play” (Clarke, 1992 p 240-245). Yet Schlegel (1846) was offended that, in his view, the saint figures poorly beside Severus. "The practical magnanimity of this Roman, in conquering his passion, throws Polyeucte’s self-renunciation, which appears to cost him nothing, quite into the shade. From this a conclusion has been partly drawn, that martyrdom is, in general, an unfavourable subject for tragedy. But nothing can be more unjust than this inference. The cheerfulness with which martyrs embraced pain and death did not proceed from want of feeling, hut from the heroism of the highest love: they must previously, in struggles painful beyond expression, have obtained the victory over every earthly tie; and by the exhibition of these struggles, of these sufferings of our mortal nature, while the seraph soars on its flight to heaven, the poet may awaken in us the most fervent emotion. In 'Polyeuctus', however, the means employed to bring about the catastrophe, namely the dull and low artifice of Felix, by which the endeavours of Severus to save his rival arc made rather to contribute to his destruction, are inexpressibly contemptible" (pp 287-288). To other critics, Polyeuctus is the very image of the intolerance of a Christian world in the ascendant, an unreason more concerned with personal salvation in metaphysical uncertainties than social harmony. “Corneille unquestionably intended to represent a change in the heroine’s feelings from a youthful romantic love of Severus- admirable enough in its way, but essentially earthy- to a nobler, higher, more spiritual love for her husband...We must recognize today that Severus is altogether the more admirable man...[even] in the realm of the spirit. Polyeuctus’ chief concern in seeking martyrdom is to enjoy the delights of heaven sooner and to avoid the danger he would run of losing them by backsliding if he continued to live...Severus, on the other hand, is actuated wholly by principle- by a love of rectitude and nobility for their own sake- when he tries to save his rival and declares that he will intercede with the emperor...[After Pauline requests this], he drops so utterly out of her thoughts and heart that when Polyeuctus had suffered martyrdom and she has become a Christian, she exclaims on learning that her father, too, is converted: ‘This happy change makes my happiness perfect’...in the presence of Severus himself, to whom, moreover, she speaks no word and pays no attention at any time in the entire scene...She feels not the slightest concern for the noble, heroic man whom she formerly had loved, who loves her still, and who has tried to save his rival for her sake” (Lockert, 1958 pp 53-57). “Severus [is an example of] “reasoned civility, a true gentleman or honest man...Severus is passionately in love, yet respectful of duty and understanding of Pauline’s commitment as a married woman and dutiful daughter. He pardons Felix’ shortsighted preference for a nobler and wealthier suitor for Pauline’s hand. He prefers justice over political expediency, clemency over justice. He admires Christian virtue and loyalty though he does not share the belief of this religious sect...In contrast, Polyeuctus lacks almost all qualities of civil virtue...At the sacrifice...an inversion of values takes place...this inversion requires a contempt of the world...We pass from Severus the reappearing hero to Polyeuctus the disappearing hero” (Lyons, 1996 pp 120-122). "Of all Corneille’s female characters, Pauline is perhaps the most attractive. She is the impersonation of duty, but also of lofty generosity, constancy, and love. Though her love for Severus still lingers in her heart, she attaches herself to Polyeuctus with the highest sense of conjugal duty. In the conflict between the old love and the new, she never allows herself to stray from her high loyalty to her husband; though she believes in the worth of Severus, so far even as to expect him to understand her in her lofty devotion" (Trollope, 1898 p 62).

"In The Cid, great scandal had been occasioned by the triumph of love- a triumph so long resisted, and so imperfectly achieved; in Horace, love will be punished for its impotent rebellion against the most cruel laws of honor; in Cinna, as if in expiation of Jimena's weakness, all other considerations are sacrificed to the implacable duty of avenging a father, and finally, in Polyeucte, duty triumphs in all its loveliness and purity, and the sacrifices of Polyeucte, of Pauline, and of Severe, do not cost them a single virtue" (Guizot, 1952 p 174). "It was by no means so much [Corneille's] object to excite our terror and compassion as our admiration for the characters and astonishment at the situations of his heroes...And here I may indeed observe that such is his partiality for exciting our wonder and admiration, that, not contented with exacting it for the heroism of virtue, he claims it also for the heroism of vice, by the boldness, strength of soul, presence of mind, and elevation above all human weakness, with which he endows his criminals of both sexes. Nay, often his characters express themselves in the language of ostentatious pride, without our being well able to see what they have to be proud of: they are merely proud of their pride" (Schlegel, 1846 p 277). “In reading Corneille, we see that the poet's aim is grandeur, and his heroes are said to have been greater than ordinary mortals. It is a shame for humanity if there are not to be found men and women animated by the noble feelings of Corneille's heroes and heroines. In the struggle between love and duty, which of the two should triumph? Let every man answer that question for himself, but let him read Corneille and take lessons in self-sacrifice, in everything inspiring. There are to be found in that poet's works the grandest maxims of morality and of patriotism expressed with a lofty eloquence. Corneille's chief qualities are sublimity in the thought and eloquence in the expression” (Fortier, 1897 p 198).

"The Cid"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 11th century. Place: Spain.

Text at http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Cid http://www.archive.org/details/greatplaysfrenc00mattgoog https://archive.org/stream/greatplaysfrench00corn#page/n23/mode/2up

Smarting for having lost the king's favor to Don Diego, Count Gormaz slaps his face. Too old to challenge him, Diego calls on his son, Rodrigo, to avenge his lost honor. "Rodrigo, do you possess a heart?" Rodrigo does. He is afire for vengeance until learning that his enemy is the father of his love, Jimena, yet he decides to follow the dictates of duty, and, despite his youth, challenges the count to a duel, because "to well-born souls, valor does not wait on years," he says. Rodrigo kills him. As her father's daughter, Jimena runs to the king and begs for Rodrigo's condemnation, while Diego begs for mercy. The king will consult his counsel. Meanwhile, Don Sancho, Rodrigo's rival for Jimena's hand, takes up her quarrel, offering to challenge him. She answers that she will await the king's decision. Yet she is tormented by thoughts of Rodrigo's fate. "My death will follow his," she says, "and yet I wish to see him punished." Rodrigo comes to offer his life for her sake, but she admits she approves him for "fleeing infamy". "By offending me, you showed yourself worthy of me," she concludes, "I must by your death become worthy of you." Despairing and longing for death, Rodrigo hears from Diego that his country needs him to battle the Moors. He agrees to go to war and is highly successful in the battles, returning as a young conqueror. Loving Rodrigo for her sake, the Infanta of Spain seeks to convince Jimena of abandoning her vengeance, since her lover has now become "the prop of Castille and the Moor's terror". Regarding Jimena, the king confides to Rodrigo that he may no longer consider losing the Cid. "I will no longer listen except to console her," he declares. The king tests her feelings by announcing the false news of Rodrigo's death, at which she swoons. Yet Jimena pursues her quest, wishing the king to declare that she will marry whoever takes up her cause in combat. He agrees provided she marry Rodrigo if he wins. Rodrigo once more offers to kill himself for her sake, specifically by voluntarily exposing himself against Sancho's sword, but she again refuses. After the encounter between the combatants, it is Sancho who presents himself before her. She reveals again her love for Rodrigo by calling Sancho an "execrable assassin" for this deed. With such proof of her sentiments, the king reveals Rodrigo is alive and the winner of the bout and her hand. Nevertheless, he defers the wedding in regard to Jimena's conflicting sentiments and to enable Rodrigo to destroy the Moors. "To conquer a point of honor fighting within you," he advises, "have faith in time, your valor, and your king."

"Horace"

[edit | edit source]

Time: Antiquity. Place: Rome.

Text at http://www.onread.com/reader/601139

To decide the outcome of the war between Rome and Alba, three warriors on one side will combat three others on the other. Despite strong ties existing between the two families, the Roman choice falls on the three sons of Old Horace against Curiace and his two brothers. Young Horace's wife, Sabina, is sister to Curiae and the latter's wife, Camilla, sister to Horace, so that the interests of the state are in mortal conflict with those of the family. On learning the news, Curiace is stricken with sadness, but to Horace it is an occasion to win glory for the good of his country. He admonishes his adversary's sadness thus: "If not a Roman, be worthy to be so; if equal to me, make it better appear so." To the equally sad Camilla he is equally severe: "Arm yourself with constancy, and show yourself my sister." When she asks her husband whether he will go to fight indeed, he answers: "Alas, I see, whatever I do, that I must die either in pain or by the hand of Horatius." He is all the more saddened after speaking to Sabina, whose husband he will either kill or be killed. Both men are admonished by the elder Horace: "What is this, my children? Do you heed flames of love and lose time with women?" The first news of the mortal combat is that Rome is defeated and two of his sons killed, the other is that Horatius fled. On seeing Camilla cry for the death of her two brothers, the elder Horace reproves her. "Weep for the other one, weep for the irreparable affront his cowardly flight prints on our brows," he declares. But to his relief, the final outcome is that Horace only pretended to flee, killing all three opponents in a death-trap, to which the elder Horatius cries out: "O, my son! O, joy! O, honor of our days! O, of the inclining state unhoped-for help!" But in Camilla's view, her country's victory is no consolation for a dead husband. In his brother's face, she curses Rome. "May heaven's wrath lighted by my wishes rain on it a deluge of fire," she prays, "may these eyes behold that thunder fall, see her houses reduced to cinders and her laurels to powder, see the last Roman at his last gasp, I alone the cause, and die with pleasure." Incensed at these words, Horace runs her body through with his sword. The devastated Sabina requests him to continue his deadly work with her. He responds that Camilla is unworthy of her tears. Despite Horace's role as savior of his country, the Roman king, Tullus, must decide whether Horace should be put to death for murdering his sister. Valerius, a Roman knight who loved Camilla, pleads against him, while the elder Horace and Sabina plead for mercy. Though an inexcusable crime, Tullus acknowledges that it is Horace's sword that makes him "master of two states". He decides to let Horatius live, provided he loves Valerius and ends his murderous spree.

"Cinna"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 4 AD. Place: Rome.

Text at http://www.archive.org/details/worksofcorneille00corn

Emilia's father had been banished by the triumvirate and died. To avenge herself on one of the triumvirate and now the emperor, Augustus Caesar, Emilia asks Cinna to kill him in exchange for her hand in marriage. Cinna prepares matters according to her wish along with a band of rebels. "May it have pleased the gods to have you see with how much zeal this troop intends so fair a deed!" he declares. However, to Emilia's anguish, Cinna's freed slave, Euphorbus, surprises Cinna by announcing that he and Maximus, the chief rebels, have been commanded to appear before Augustus. "Go, and remember only that I love you," Emilia swears to Cinna. Before Augustus, Cinna pretends to approve his rise to complete power. "The worst of states is a popular one," he states, to which the emperor replies: "And yet the only one which can please Rome." "My lord, to save Rome, she must unite in the hand of a good leader to whom everyone obeys," Cinna retorts. Pleased with both men, Augustus makes Maximus governor of Sicily and gives Cinna Emilia's hand in marriage. But the donors change nothing of Cinna's resolution of cutting the evil to the root by freeing Rome of tyranny. However, Maximus, in love with Emilia, tells Euphorbus that the emperor's death will only serve his rival, whereby Euphorbus advises him to betray Cinna to Augustus. Maximus hesitates to take that course because of his friendship with the other conspirators. "I dare all against him but fear everything for them," he says. Emilia is relieved to learn Augustus suspects nothing, but when Cinna starts to speak of the emperor's goodness, she cuts him short. "I see your repentance and your inconstant vows: the tyrant's favors gain a victory over your promises," she states. On the contrary, Cinna is pushing her designs forward: "Caesar, stripping himself of sovereign power, would have removed any pretext of our piercing his breast." He accepts her demands, though "Augustus is less of a tyrant than you," he says. Augustus learns from Euphorbus that Maximus is a repented conspirator but that Cinna seeks his life. Yet the emperor's wife, Livia, recommends clemency. Wearied of these troubles, the emperor wishes either to abdicate or to die. "What, you would abandon the fruit of so many pains?" she asks. "It is the love of greatness which makes you importunate," he accuses. "I love your person, not your fortune," she assures him. Rumors circulate that Maximus is dead, but Emilia is surprised to find him alive. His presumed death, he explains, is Euphorbus' plan to keep him still alive. He proposes that they leave Rome together along with Cinna. "Do you know me, Maximus, and do you understand who I am?" she proudly asks. At last he reveals his love to her. "You dare to love me and do not dare to die!" she exclaims. To end the matter, Augustus asks for Cinna one more time. He reminds him of their bonds. "You live, Cinna, but those to whom you owe your life were enemies of my father and mine," the emperor reminds him. "You were my enemy before even being born...I avenged myself only by giving you life." He accuses Cinna of plotting his death. Cinna denies it. Undeterred, Augustus goes on to name all the conspirators and asks him why he joined them. Knowing himself betrayed, Cinna admits he should be executed. Emilia confronts Caesar by declaring that Cinna's plot was all for love of her in avenging her father's death. "Reflect with how much love I raised you," he admonishes, to which she replies: "He raised you with the same tenderness." "His death, whose remembrance fires your fury, was Octavius's crime, not Caesar's," Livia counters. Not to be outdone in honest revelations, Maximus enters to confess his treachery against a rival for Emilia's love. Despite the dangers of such plans against his life, Augustus feels the greatness of his magnanimous soul. "I am master of myself as well as the universe," he declares. He names Cinna to the consulate and gives him Emilia's hand in marriage, which the repentant Maximus agrees with. "More confounded by your bounties than jealous of the good you take from me," he declares in admiration of his master.

"Polyeuctus"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 3rd century. Place: Armenia.

Text at http://www.bartleby.com/26/2/ http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/2543

Thinking that a worthy warrior, Severus, died during Rome's war against Persia, Felix, Roman senator and governor of Armenia, marries his daughter, Pauline, to Polyeuctus, an Armenian lord with an inclination towards Christianity, though at this time unrevealed. However, Severus is alive. Very worried that he might exact vengeance on them all for handing his love over to another, Felix requests Pauline to see him, which she accepts, though bitterly complaining. "Yes, I will once more master my feelings, to serve as victim to your rulings," she states accusingly. Although her marriage was the result of a father's command, Pauline asks Polyeuctus not to see her ever again: "Spare me the tears that fall to my shame," she pleads, to which he sadly agrees. "Farewell. I will find in the middle of combats that immortality which a beautiful death yields," he declares, urging her to restrain her tears. She responds that she still has reason to fear, as one half of her dream has already come true: Severus is alive, the other half being Polyeuctus' death. Felix orders Polyeuctus' presence at a pagan sacrifice. This is discouraged by Polyeuctus' Christian friend, Nearchus, who wants him to flee from such altars. Polyeuctus agrees, because he has a strong and dangerous desire to pull them all down. Nearchus reminds him that such a deed means death. To her horror, Pauline learns from her confidante that Polyeuctus has indeed accomplished his wish, and was joined by Nearchus, "the most powerful of gods by an impious hand pulled down at their feet," she cries out, yet she remains loyal to Polyeuctus. "I loved him in duty, that duty lasts still," she states. Felix is indignant at Polyeuctus' act. Fearing the gods and Emperor Decius, he immediately orders Nearchus' execution and enjoins his daughter to convince Polyeuctus to abjure. "Your only enemy here is yourself," she reminds her husband. But he rejects thoughts of wordly advantages. "One day on a throne, the other in mud," he pronounces, his ambition now being immortal, which she calls a Christian's "ridiculous dreams". Moreover, she pleads that his life belongs to his sovereign and the state, to which he counters: "I owe my life... much more to God who gave it to me." "Adore him in your soul and show nothing," she enjoins him. "That I should be both idolater and Christian!" he exclaims. She reminds him of his love of her. "Is that your lovely fire? Are those your vows?" she asks rhetorically. "In the name of that love, follow my steps," he enjoins her. But to her mind, these are "imaginations" and "a strange blinding". Severus enters in response to Polyeuctus' request to give her back to him after his martyrdom, but she refuses to consider it, he, however innocently, being responsible for her husband's likely death. Severus magnanimously asks Felix to spare Polyeuctus, but the latter fears the emperor. Felix enjoins once more Polyeuctus to abjure, who answers that to a Christian "their cruelest torments are rewards". Felix then asks him only to pretend to abjure until Severus leaves, words which he considers "sugared poison". All pleadings by Felix and Pauline are without effect. He is conducted "to death" according to Felix, "to glory" according to Polyeuctus. After witnessing his execution, Pauline challenges her father. "His blood, which your executioners just covered me, has disjointed my eyelids and opened them," she says, and requests him to kill her. Severus enters angry and threatening. Abashed, Felix gives up "his sad dignities", acknowledging Polyeuctus' God as "almighty" and choosing to follow his daughter as a Christian, to her joy and Severus' admiration.

Alexandre Hardy

[edit | edit source]Also of interest as a tragedian is Alexandre Hardy (1570-1632). Unlike the polite manner of the French neo-classic period, Hardy is characterized by verbal onslaught and a definite bent for open stage violence, nearer English Renaissance plays than French versions. In particular, Hardy wrote "Scédase" (Scedasus, 1624) on the consequences of treachery and rape.

The play’s final scene presents Scédase’s desperate suicide as a consequence of the Spartan king Agésilas’s failure to condemn the men. Although the king’s presence is marginal to the overall plot, and the trial scene itself is short (spanning only 34 verses within a 1,368-verse play), the royal decision pinpoints the king’s power to determine the outcome of the legal and theatrical argument. At the close of Scédase, the audience is left with a bitter sense of the expediency of royal judgment and the tragedy it can provoke...The opening of act 5 where the king appears onstage addressing Scédase kindly and professes a deep concern for equity seems to foreshadow an in extremis castigation of the guilty men. Agésilas assumes the role of the supreme judge, announcing that he will show no favouritism in the judicial procedure that he prepares to undertake...The king’s reference to the blind justice of the goddess Themis, as well as his assurances that all who come before him are judged according to an ‘equal measure’ draws on commonplace images of justice associated with impartiality...Yet, Agésilas’s justice is quickly separated from the realm of divine justice, and instead firmly situated in socio-political and economic realities. Exposing a view at odds with the ideals embodied by the blind goddess Thémis, the king undermines his pledge that all who come before him should be judged equally when he insists on the particular punishments he would dispense to criminal noblemen...Rather than a spectacular demonstration of the king’s power to intervene, the hyperbolic retaliation against the guilty which would change the course of the dramatic action for the better, Agésilas articulates a convoluted vision of punishment. This passage reveals the acute distinctions the king makes between the peasant who comes before him, asking for justice, and the accused noblemen. The king’s insistence that even if Scédase were of an even smaller status, he would still protect him, emphasizes his awareness of the father’s lowly social condition and the underlying social clash underpinning the case. The special punishment the king reserves for noblemen who have the souls of commoners puts into doubt the equity of Agésilas’s ultimate decision to not even attempt to locate the Spartan men. The king’s refusal to take on the role of the wise judge ends the trial scene with the disconcerting conclusion that the accused will never be made to answer for their actions” (Nathan, 1935 pp 51-53).

“Hardy, great baroque playwright, was one of the first to speak out on sexuality, society and the class system. Yet, having often been compared to Corneille whose predecessor he was, Hardy was put aside as a poor substitute. The time having come to restore his place of honor, it is not at all surprising that this took place in the contemporary period when deviance of the norm is recognized as a quality” (Anonymous reviewer, 1977 p 229).

"Hardy, the founder of the Parisian stage and the precursor of Corneille, was not one of those men whose genius changes or determines the taste of his age; but he was the first man in France who conceived a just idea of the nature of dramatic poetry. He understood that a theatrical piece ought to have a higher aim than merely to satisfy the mind and reason of the spectators and he was at the same time of opinion that carefulness to employ their senses and excite their imagination should not prevent the play from being regulated by reason and probability" (Guizot, 1952 p 120).

“As a maker of plays, Hardy chose to override the pedantically imitative neo-classicism of earlier academic writers like Etienne Jodelle and Robert Garnier: he ignored the unities of time and place, banished the chorus, depicted deaths on stage instead of reporting them, and admitted comic, low-life characters and incident to his tragedies. In these respects he resembles Lope de Vega, Calderon and the English Jacobean playwrights; but in one fundamental respect he provided his successors in France with something unique in European dramaturgy: simple and concentrated plots of a kind rarely even attempted elsewhere” (Wickham, 1994 p 148).

Hardy’s “heroes are interesting because they call forth sympathy, not merely pity. They are much more active physically and mentally than are the tearful automatons of the sixteenth century. The rehabilitation of the hero from the bloody villain of Italian tragedy into the man or woman worthy of respect had taken place; and Hardy was responsible for this welcome development. Yet his whole system of dramaturgy was not capable of arousing poignant suspense as to what will happen and how it will happen. One is simply curious as to when the impending doom will fall. Hardy lacked the ability to combine the interplay of psychological reaction and events so as to arouse alternate hope and fear for a person who has won our sympathy. In spite of his power in selecting scenes and arranging them in an order which tells the story effectively, his characters do not grow and develop with fine gradation. Questions of life and death are discussed but decisions are arrived at too suddenly. There is no cumulative effect of hope and fear to constitute suspense. Without cumulation there is merely curiosity” (Stuart, 1960 pp 368-369).

"Scedasus"

[edit | edit source]

Time: Antiquity. Place: Sparta and Leuctres, Boetia.

Text at ?

Against the advice of an old man, Iphicrates, two young men, Charilas and Euribiades, have fixed their eyes on two sisters, Evexippa and Theana, and so leave Sparta to court them in a Boetian village. Scedasus, father of the two sisters, leaves the village to attend to business, recommending them to keep their virgin honors safe while Charilas and Euribiades are welcomed inside his house. Scedasus scoffs at his daughters' anxieties concerning this arrangement and leaves as the two youths arrive. Charilas is overjoyed, exclaiming: "O, celestial place! Since your sight, alas, I have not seen the day." Iphicrates follows them in the village and immediately worries over their lascivious bent, but Charilas assures him that they intend no dishonor to the two sisters. "You will sooner see fire born of ice, or earth dislodge Olympus from its place," he swears. The sisters welcome the two men, Iphicrates approving the women's modest answers, disinclined to lend ear to men's flatteries. The youths are quickly frustrated in their desires. To get Iphicrates out of the way, they request him to return to Sparta for the specious reason of reassuring their parents about their safety. Once the old man goes, Charilas boldy expresses what they want from the two sisters. "You are our sickness, and our remedy, too," he avows. Euribiades assures Theana of his intention to marry her, beseeching her to "fly from the odious example of an icy rock". Nevertheless, both Theana and her sister reject their offers. Furious, the men threaten both with rape, but the sisters would rather die than submit. Despite their intent, Euribiades rapes Theana and when both sisters scream to alert the villagers, he kills her. Unwillingly, Charilas murders Evexippa, then both men transport the bodies elsewhere. When a neighbor discovers their corpses inside a well, the returning Scedasus faints in despair. He then revives to exclaim against Jupiter: "Such an act in your presence unpunished proves well that the universe has no head that rules," he declares, "that everything rolls haphazardly, without order or justice, that the most virtuous are the most outraged." He travels to Sparta along with friends to plead his case before the king and magistrates, but, lacking eyewitnesses, these refuse to believe that such a noble family would commit such crimes. In despair of finding justice, Scedasus kills himself above his daughters' tomb.

Jean Mairet

[edit | edit source]

Mairet reached creative heights with "Sophonisbe" (Sophonisba, 1634) about a queen subject to divers troubles as a result of being suspected of adultery.

“The episode in Livy, where the story is told of the Carthaginian Hasdrubal's beautiful daughter Sophonisba, how she marries, for the sake of her country, the king of the Massaesylians, Syphax, how after the defeat of Syphax, she becomes infatuated with Masinissa, the confederate of the Roman her tragic end, as she takes the poisonous cup offered by despairing lover, is a subject which has been treated by many dramatists. Before Mairet, six tragedies on Sophonisbe had appeared in France, but none of them equals the skillful composition of Mairet” (Blume, 1892 p 72).

The plot of "Sophonisba" "is found in Livy and interpreted by Trissino (Sofonisba, 1515) and others...The story's past is made up of the long history of hate between the Romans and Carthaginians, the Roman conquest of Africa, and the haggling, in Roman politics, over crowns and alliances; it is also made up of the long years during which Sophonisbe, married to Syphax, awaits Massinisse...These characters are doomed to disaster because they are acting against Rome, in spite of Rome, or forgetting Rome altogether. Taken superficially, the trio Syphax-Sophonisbe-Massinisse leads to a highly romantic adventure, similar to certain tragicomic plots: a prince charming, for whom a queen betrays her old loving husband in the midst of the war, the delights of requited love, and a brutal peripety that cruelly separates the lovers. But beyond the romantic, that adventure is constantly subjected to the Roman judgment, to the threat of Roman punishment. The love story, which has its own crimes and joys, is up against the necessities of another order, which- in its real power over the destiny of men- is superior to it...Mairet's play is notable for the progressive nature of Sophonisbe's awareness of the peril and its intensification in the spectator himself...Indeed, parallel to the intensification of the Roman peril and its 'political' presentation, Mairet gradually develops and enriches a love story in which the characters aim not at conquering Rome but at eluding her, at acquiring an inoffensive independence- that is, happiness outside of history...Mairet's play is, for the most part, a description of the anxious expectations of love, the wondrous impetuosity of love at first sight, and the satisfaction and plenitude of its final fulfillment. In itself the love of Sophonisbe and Massinisse is altogether sensual and sexual- a conception of love without complexes, similar to that of the Renaissance, and not yet degraded or stifled by the Jansenist atmosphere, or even idealized by the super-structures of Corneille" (Guicharnaud, 1967 pp 206-211).

“The story of the historic Sophonisbe and Massinisse is found in the works of Livy and Appien of Alexandra...Mairet...made more use of the account...by Appien...The principal problem [with the historical account] lay in the fact that Sophonisbe’s marriage to Massinisse made her bigamous, since Syphax was still alive, [so that in Mairet’s play Syphax dies]...Another major modification is that [Massinisse commits suicide soon after his wife’s], although the true Massinisse lived long after...Scipion and Lélie argue that duty to the state stands first in order of importance. Opposing them, the lovers attempt to establish that love must be placed above all...Massinisse’s decision to marry Sophonisbe represents a renunciation of the values that have created the Roman empire...All of the author’s talents appear at their best advantage in the tragedy...His power of creating human characters succeeds admirably in the portrait of Syphax, the embittered and jealous old man, Massinisse the glorious hero and ardent lover, Scipion and Lélie, soldiers devoted to duty and the cause of Rome, and Sophonisbe, the heroine” (Bunch, 1975 pp 104-110).

“The two lovers share their passion to the full before the arrival of Scipio, who judges and condemns their passion. And since they have elected to put their whole lives, their very existence, as it were, into passion, they have no other choice but to die. In the original, the drama was much less symbolic. As Livy tells it, only Sophonisbe died; both Syphax and Massinisse lived on afterward, and the latter's hasty marriage to Sophonisbe was treated as folly, something which could easily be rectified...Both Sophonisbe and Massinisse are African, young, handsome, passionate. Scipio, on the other hand, is Roman, and it is a curious fact that although Livy specifically mentions his youth, good looks, and magnetic personality, Mairet has changed him into the embodiment of Roman discipline and order, cold, intractable, the perfect enemy of passion. Thus the Punic Wars between Rome and Carthage also lend themselves to symbolic interpretation, in the triumph of intellect over the senses. The character of Syphax fits into both the dramatic and the symbolic situation. An African, he had always kept an alliance with Rome, until his marriage with Sophonisbe, and he dated his misfortunes from the day of his marriage. As a king, he had failed to reconcile his wife's political interests with those of Rome, and was not strong enough to withstand the Roman military attacks. As a man, his marriage to the young Sophonisbe had been a disaster, because of the discrepancy in their ages. He appears in the first act exactly what Massinisse calls him ‘that barbaric and cowardly usurper’ in the sense that he had prevented the young couple from marrying years before. A measure of Syphax's failure - he has not been able to be true to either reason or passion- may be gained by the virulence with which he spits out his hatred of Sophonisbe...Syphax is not just jealous at being betrayed by his wife, who, as he knows, is in love with Massinisse. She has destroyed him from within just as the Roman armies are destroying his country around him. Only Sophonisbe could bring about this physical and moral disintegration: ‘much more than my body my mind has grown old’ [he says], to leave him a charred, empty ruin, with nothing but hatred for her beauty, and Syphax in his impotent rage can think of nothing more horrible to wish on his rival than to go through the same experience: ‘to hand you a present worthy of an enemy and to wish you worse than steel or fire, I wish you Sophonisba as wife.’ Thus, the first condemnation of passion comes not from the intellect, but from the emotions, from a person who has tried and failed to come to terms with passion...[Sophonisbe] knows that time is working for Massinisse and against Syphax. Time is on the side of passion, which has taken on the character of a destiny, irreversible. One cannot go back, one cannot reverse the movement of passion. It is extraordinary how Mairet has in this play instinctively understood the unity of time, not merely as a technical innovation (which it was, for contemporaries), but as a dramatic, as well as a psychological and symbolic necessity. Everything in the play hinges on the tremendous force created by the compression of time - one has the feeling that human lives are being lived out in the space of a few hours, that every decision, every act carries an enormous importance, far beyond its normal significance...Scipio's reasons are all too cogent: Sophonisbe, a sworn enemy of Rome, had turned Syphax against his greatest ally, and could easily do the same to Massinisse, so that a marriage between them was politically out of the question. But at a deeper level, passion, by its very existence, poses a threat to the forces of reason. No compromise is possible between Carthage and Rome, no reconciliation between passion and reason can be effected. The gulf between the two is unbridgeable...The two men cannot communicate with each other; how could they? They do not speak the same language. Massinisse's arguments, except for one claiming a right to Sophonisbe as a payment for past services, are all based on an emotional appeal, just the kind which would have no effect on a mind like Scipio's. And as he sees he is making no impression on Scipio, Massinisse does just the wrong thing: he becomes more and more emotional until he reaches a state of incoherence...The duality between intellect and the senses is so deeply ingrained in us, that any work of art directed to a general audience must take it into account. Mairet has given audiences, in Sophonisbe, a tragedy which satisfied these opposing exigencies. His audience could respond whole- heartedly to the beauty and eloquence of the lovers' emotions; it could feel the weight of their tragedy, while at the same time experiencing a secret satisfaction in knowing that their downfall was inevitable. It still seems somewhat ironic that the triumph of reason, supposedly man's highest faculty, over passion, should be perceived and accepted as material for a tragedy” (Kay, 1975 pp 39-45).

"There is no question in the play of Sophonisbe hesitating between her husband and Massinisse. Syphax reproaches her bitterly for her infidelity to him, but when she later confides in Phenice it is obvious that her thoughts are concentrated exclusively on Massinisse...Far from endeavouring, like Pauline and Phèdre, to struggle against her passion, Sophonisbe's sole fear is that Massinisse may not fall a victim to her charms...During the first three acts of 'Sophonisbe' everything happens as foreseen in the first act. The battle is won by the Romans, Syphax is killed and Massinisse, leader of the victorious army, falls in love with Sophonisbe and marries her. Not once does a critical situation halt or hinder this smooth succession of events. The purpose of these first three acts is in fact to lead up to the crisis which at last occurs in the fourth act. Each character in turn lays emphasis on the strange nature of the relationship between Sophonisbe in one camp and Massinisse in the other...This crisis is quickly ended during the last one and a half acts, for Sophonisbe plays a completely passive role, totally unlike that of Chimène in Le Cid, and Massinisse, after a few vain protests and complaints against Scipion's decision, finally avoids the issue by adopting suicide as the easiest solution for both himself and Sophonisbe...Before the end of the first act of Le Cid Rodrigue finds himself in a situation analogous to the one with which Massinisse is faced only in the fourth act. Moreover, instead of yielding weakly to circumstances, Rodrigue does as his father commands and his decision has its effect upon the forceful personality of Chimène, whose resultant actions have repercussions upon Rodrigue's conduct. A single act is thus devoted to events leading up to the crisis and the remaining four acts to the involved efforts to find a solution to the problems arising out of it" (Chadwick, 1955 pp 177-178).

“The long and powerful interview between Massinisse and Sophonisbe in act 3 is one of the earliest uses of a climactic confrontation between the two most active characters...Their decision to marry…prepares the confrontation in act 4 with Scipion” (Gethner, 1986 p 1251). “Massinissa enters rather late in the play, but there is no reason for having him appear earlier. The plot happens to be one in which these rules can be observed without the loss of dramatic value. Only the hurried second marriage is dangerous to handle and Mairet was conscious of this pitfall. There are enough events to sustain the interest to allow the characters, going through different phases of emotion, to be active in developing the situation...[In the development of French tragedy], the dramatic struggle has begun to enter the human mind instead of merely using the human body as a shuttlecock. Events in the plot have begun to follow each other psychologically, not merely temporally. Things have begun to happen because the hero and heroine think in a certain way, and not merely because they are shipwrecked or captured. Mairet’s Sophonisbe is the most artistic French tragedy up to the time of its production, not, as Chapelain would have said, because it observes the unities, but because by observing the unities Mairet made the play a dramatic tragedy which unfolds partially in the human heart” (Stuart, 1960 pp 383-384). "It is difficult, at the present day, to divine what lucky chance dictated Mairet's 'Sophonisbe', the only one of his pieces in which he rises at all superior to the taste of his times. Its merits taught nothing to its author, to whom it was nothing more than a piece of good fortune but there is reason to believe that it revealed to Corneille the powers of his own genius" (Guizot, 1952 146).

"Sophonisba"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 2nd century BC. Place: Numidia (north Africa).

Text at ?

Syphax, king of Numidia, accuses his wife, Sophonisba, of conducting an adulterous relation with his Numidian rival, Massinissa, having found her incriminating letters whose characters constitute "accomplices and witnesses of adulterous fires", all the more dangerous in view of an imminent Roman attack. Sophonisba defends herself by stating that her love for Massinissa was feigned to help her husband against the Roman army. Syphax disbelieves her but does not punish. Aligning himself with the Romans in an armed battle, Massinissa defeats Syphax who is killed. The victor is subjugated by Sophonisba, wishing her to become his queen rather than his captive. Their marriage is precipitated by Massinissa's fear of Scipio, the Roman counsel, likely to disapprove of this dangerous match, especially in view of Sophonisba's presumed treason against her husband and her leading him away from Rome's interests. Scipio request Massinissa to annul the marriage, but he refuses. Instead, Massinissa pleads the Roman counsel to allow it. In response, Scipio condemns her to death. Scipio's lieutenant, Lelius, begs Massinissa to allow Sophonisba to die, but Massinissa refuses. Instead, knowing Sophonisba will poison herself should he fail to convince Scipio of approving their marriage, Massinissa sends her a letter describing his failure. On receiving it, Sophonisba poisons herself, the letter being for her "the final witness of my fidelity". On learning of his wife's suicide, Massinissa stabs himself to death, "ceasing to die by ceasing to live," he declares.

Théophile de Viau

[edit | edit source]

Viau wrote a single play: "Pyrame et Thisbé" (Pyramus and Thisbe, 1623), based on a story in the epic poem, "Metamorphoses", by the Roman author, Ovid (43 BC-17/18 AD), and treated as a tragedy, unlike the comedy of the play within the play presented in Shakespeare's "A Midsummer night's dream" (1595).

"Pyramus and Thisbe", "though disfigured by those conceits which the Italian Marini- an honoured guest at the French court- and the invasion of Spanish tastes had made the mode, is not without touches of genuine pathos” (Dowden, 1904 p 138).

“Traces of vocabulary can be used as proof that Thisbe is looked upon by our poet as Cupid's saint. But these are minor in comparison with the overwhelming evidence present in the whole structure and conception of the poem. It begins with a traditional Ovidian description of the symptoms of love, with the whole battery of Ovidian images, the darts, the arrows, etc. Indeed, there are no herbs, no juices, no medicine; there is no doctor who can prevail against the god of love. We soon see that it is a question of a religion of love here and that Venus is worshipped by Pyramus as a goddness to whom he prays and makes vows, promises and sacrifices. Then the poet shifts somewhat abruptly to Thisbe and an element enters into the tale not present in Ovid. Over and over again Thisbe insists upon her intention to remain chaste...We should not overlook, either, the ritualistic elements present in the poet's narration of the tale. This is seen not only in Pyramus’ devotions at the altar of Venus but in the ritual of the love tryst. The lovers, having sealed their covenant, agree to meet at the fountain, the place of cleansing through ‘baptism’ or, more probably, through the sprinkling aspects of the last rites, as is revealed by Thisbe's statement regarding the fountain: ‘that made me healthy’...But the most powerful passages of the poem are found in the death scenes, where, just as in Tristan, we have an ecstatic paroxysm, made more poignant still by the extreme youth and chastity of our protagonists, two lambs offered like sacrificial victims to the god of love...The complex concept of nature found in other works of Théophile is reflected, too, in the idea Pyramus has that he must leave things up to nature which has formed him as well as Thisbe...Baroque predilection for metamorphosis is everywhere present in the play of Théophile, but the ultimate metamorphosis is, of course, the one of the mulberry tree, inherited from Ovid and retained by Théophile not only for its ritualistic values but because it, along with other radical changes which Thisbe apprehends around her, accords well with the role we have seen nature to have in this particular version of the tragic tale...Thisbe is furthermore aware of the cyclical nature of the tree, which dies every year and flowers once again each year, a cycle which she and Pyramus will not partake of, except vicariously in the symbol of the tree...Théophile' play is indeed very worthy of our attention, and, ironically, no French play has closer connections with Shakespeare than this one, whose tragic events are so like those portrayed in ‘Romeo and Juliet’. Although it is unlikely that Théophile knew the plays of Shakespeare and although it was virtually impossible for him to have known the 12th century French poet, Théophile has come very close to both of these in the portrayal of chaste and sacrificial love which does not balk at pushing its victims even to suicide to prove itself" (Pallister, 1974 pp 126-131).

"Pyramus and Thisbe"

[edit | edit source]

Time: Antiquity. Place: Babylon.

Text at ?

Thisbe is spied on by her mother's servant, as she suspects her daughter of harboring a secret love. Irritated at the servant's prudent comments, Thisbe calls her an "old bony specter" and leaves her abruptly. The king reveals to his subject, Syllar, his love of Thisbe, but is frustrated of his success because of a rival, "a simple citizen", whom he will arrange to kill. Syllar proposes to do it. Much like Thisbe with her servant, Pyramus is equally irritated at the prudent suggestions of his friend, Disarque, with which he refuses to comply. "May your judgment work to preserve my disease," he prays. Although Disarque conjures him to be careful, as he is spied on, Pyramus meets Thisbe, who, advancing cautiously, asks: "Is it you, my trouble?" The lovers bemoan the old ever crossing the young, he cursing that "the old erect impotence under the title of virtue". While they agree to meet again soon, Syllar attempts to convince his partner, Dexis, of helping him murder the king's rival. However, in Dexis' opinion, a king is no more allowed to sin than any subject. Syllar argues that since the king knows the two are privy to his murderous thoughts, they are in great danger unless they execute his orders. Unwillingly, Dexis joins Syllar in attacking Pyramus, who counters by stabbing to death Dexis and wounding the fleeing Syllar. In remorse of his attempted deed and before dying, Dexis warns Pyramus that the order to kill originated from the king. As a result of this revelation, Pyramus easily convinces Thisbe to escape with him away from the country. He admits his extreme jealousy. "Should I please my jealous designs," he says, "I would prevent your eyes from looking at your breasts." They agree to meet at night near the tomb of Ninus, Babylon's founder. Meanwhile, Thisbe's mother, on the strength of a mere dream, regrets her intolerance of her daughter's love. Too late. Pyramus arrives first and is horrified on seeing traces of Thisbe's footsteps and veil marked in blood and mixed with traces of a passing lion, at sight of which, despairing, he stabs himself to death. When Thisbe beholds her dead love, she only wishes to follow him. "I see that this rock has burst itself with grief, to spread tears, to open up a coffin," she moans. She retrieves his knife and stabs herself to death.