History of Western Theatre: 17th Century to Now/Boulevard of the 20th

“The period which extends from 1890 to the war of 1914 remains that of Antoine's Theâtre Libre, of plays with a message (Hervieu, Brieux), of ideological dramas (Francois de Curel, Marie Leneru) and for more frivolous spectators, that of boulevard theatre, which came into full flower at the beginning of the twentieth century. Life then had a meaning. One sought to define it and to preserve it from adulteration. It was not long since the advocates of the experimental novel had proclaimed themselves the doctors of society. Playwrights took themselves no less seriously: the Church, the army, the laws, everything was made a topic of debate upon the boards. At the same time, studies of manners and society went on apace. There is no evidence that in France curiosity about the individual has ever waned. Porto-Riche, Bataille, Bernstein were the fashionable writers. Nonetheless there were pure entertainers. With no other goal than to amuse a public which an era of peace allowed to laugh without any mental reservations, they continued to shoot off gaily all the fire-works of their wit. The plays of Flers and Caillavet and those of Alfred Capus represent perfectly this type of comedy. It was as scintillating but also as ephemeral as the bubbles of the champagne whose flavor it possessed. In a more daring genre, Georges Feydeau, Maurice Hennequin, Pierre Veber supplied the Palais-Royal with hilarious vaudevilles” (Coindreau, 1950 pp 27-28).

In the early 20th century, French farce is bolder than that of any other nation. As Nathan (1915) pointed out, “the difference 'twixt a risqué American farce and a risqué French farce is simply this: in the former the plot proceeds toward adultery, in the latter the plot proceeds from adultery. Or, in another phrasing, the American product deals with adultery as a probability of the immediate future, while the Gallic product deals with the probability of adultery of the immediate past being found out” (p 4). In the French version, the sex act has already occurred, in American or British versions, it is only threatened to occur and often never happens. For the Anglo-Saxon public, marriage is a sacrament and institution unmeet to be laughed at, for the French often a joke.

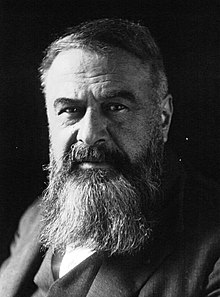

Georges Feydeau

[edit | edit source]

Georges Feydeau (1862-1922) continued his dominance over Boulevard theatre from the previous century with "Une puce à l'oreille" (A flea in her ear, 1907), bitingly satirical and with elements of cruelty most of the genre lack.

In "A flea in her ear", “there are 724 comings and goings…The pace, particularly the second act, is literally breathtaking. Spectators are subjected to viewing so much chaos, so much movement, so many complications, so many encounters, so many breakneck chases, so many gasping and panting characters that in the end they are themselves left breathless and physically exhausted” (Esteban, 1986 p 602-603). “Feydeau piles complication on complication and what should lead to clarification only help to confuse...Feydeau presents a tableau of alcoholism, prostitution, sexual perversions or inadequacies, and a general attitude toward life which reflects, on the bourgeois level, the same preoccupations that naturalism reveals...The seventh scene of Act 2 is pure nightmare, as the characters are plunged into the absolutely incomprehensible and we the audience attacked though our nerves by the absurdity and extremity of the situations in the most violently physical of vaudevilles. Tournel, turning back from locking the door so that he can better violate Raymonde, leaps onto the bed, which in the meantime has revolved, and finds himself embracing Baptistin. For him as for Raymonde on the other side of the wall, there can be no explanation but madness” (Pronko, 1975, pp 162-164).

“Feydeau offers a play in which neither husband nor wife is even seriously contemplating adultery. Yet it is suspected adultery that sets Feydeau’s infernal machine in motion...Raymonde advocates a double standard usually attributed to and associated with men: she can understand and excuse her cheating on her husband but would not stand for it if the reverse were true. She truly believes that a lover would be satisfied with the gift of her mind and heart...For Chandebise, whose only flaw...is...his conjugal duties, the punishment is utterly out of proportion. Like a Kafka character, he is assailed by unknown forces for incomprehensible reasons” (Esteban, 1983 pp 134-135).

"Feydeau exploits sexuality for its ability to stimulate physical tension throughout the act. His use of the Englishman, Rugby, in this enterprise is particularly interesting. Established from the onset as satyrism incarnate, Rugby is always on the prowl, his door left invitingly open: a trap which Raymonde, Antoinette, and Lucienne all enter...Raymonde and Lucienne both fight their way back out immediately, but Antoinette, the fun-loving maid, stays on after Camille fails to rescue her, later rushing out with her blouse clutched around her when her husband stumbles into the room. It is Rugby who is also one of the most violence-prone characters on stage, wrestling with all the women and brutally assaulting Camille and Etienne and Chandebise...Feydeau handles psychology well, but his real genius lies in the aesthetic structuring of physical movement...His characters constantly change direction, running first for one door, then racing for another. They also chase up and down the stairs- twenty-four times in all...Feydeau uses choreographic distancing...to create a sense of detachment in the audience...An example...occurs...as Chandebise himself, arriving at the hotel, temporarily escapes from Histangua by taking refuge in Rugby's room. The Englishman, interested only in having girls in his room, shoves Chandebise out- and the noise of their struggle attracts Ferraillon, the owner, to the scene....Feydeau makes the physical action into an ensemble dance...building of the physical tension he has so artfully created into a kinesthetic climax...Feydeau himself announced the principal rule of construction for his intrigues: 'when two of my characters absolutely must not meet, I bring them together as soon as possible.' It should be added that he always throws them together literally nose to nose, with a sure sense of theatrically effective movement. Thus, when Raymonde and Tournel first meet in the bedroom of the hotel, Feydeau goes to great lengths to make sure that they will not at first see one another across the room but face to (bruised) face...Feydeau uses this principle eight more times in the act...As Eric Bentley has correctly postulated: 'the theatre of farce is the theatre of the human body' (The life of the drama. New York: Atheneum, p 252, 1970). As much as any other dramatic form, farce reminds us that theatre remains more a Dionysian ceremony than an Apollonian one" (Parshall, 1981 pp 359-364).

The malfunctioning of the revolving bed “is an excellent demonstration of the Bergsonian view that as a man begins to resemble a machine so he becomes less human and increasingly an object of laughter. In this case, and in complete harmony with the extremism of farce, man no longer commands the machine; it commands him; indeed, Camille and Baptistin have become a part of it, subsumed into the machinery as it spins heedlessly out of control” (Booth, 1988 p 147).

“Feydeau’s first acts are marvels of preparation. Stealthily and unobtrusively, he weaves a complex fabric in which all subplots are not only interrelated but also inseparable from the main plot, so that nothing happens to anyone without affecting the others. Every detail is carefully and meticulously orchestrated so that almost all characters introduced in the first act have a good, often inevitable reason for being where they will encounter the person or persons they least expect to wish to see” (Esteban, 1986 p 599). Feydeau’s characters “plunge themselves into situation after situation with nearly tragic abandon. They want desperately to escape the tedium of daily living and of course most of them choose sex as their means of escape. Feydeau sees tragedy behind the farce of bed-hopping but his characters do not, although many of them face up to their own folly” (Marcoux, 1988 pp 141-142). “Situational comedy...at which Feydeau excelled...is placed...below the level of the comedy of character. The reason for this is given by Bergson (1913). The purpose of laughter...is to correct behavior that is dehumanized or antisocial...A character...fails to adapt to changing circumstances...betrays his mania...Situational comedy, on the other had, reveals a distraction in things, life is seen as a mechanism with interchangeable pieces and reversible effects...Unlike the comic of character, says son, situational comedy corrects nothing...In the last half of the 20th century, life has become so dehumanized that Feydeau’s plays stand today almost like a revelation of the threatening universe in which we live...Everything allows us to concur, for life seen...through the perspectives of the Theater of the Absurd...suggests that there is indeed a natural stiffness of things...Writers like Beckett and Ionesco have suggested that [situational comedy] has metaphysical implications” (Pronko, 1975 pp 48-50). Yet there is a distinction to be made between Feydeau and the Theatre of the Absurd of the Ionesco kind. “The absurd in farce, which is a momentary suspension of order, is not synonymous with the existential Absurd which indicate logical absence of all order. The distinction is comparable to that which exists between crime and anarchy, or between blasphemy and atheism; the first is an assault on a code, while the second is a denial of the code” (Farrell, 1995 pp 311-312).

"A flea in her ear"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1900s. Place: Paris, France.

Text at http://olathetheatre.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/A-Flea-In-Her-Ear.pdf

As a result of her husband's impotence towards herself, Raymonde Chandebise suspects him of having adulterous relations. To test that idea, with the help of her friend, Lucienne, she composes a letter from an unknown woman for a lover's rendezvous with him at the Minaret Galant. Chandebise cannot believe the letter is meant for him, but rather for his friend, Tournel. By chance, Chandebise shows the letter to Lucienne's jealous husband, Homenidès. "Caramba!" he cries, "My wife's writing!" Homenidès warns Tournel to avoid going there, but yet Tourney does. When Raymonde arrives at the Minaret Galant, she asks for Chandebise's reserved room, as does Tournel when he arrives. While sitting on the bed, Tournel draws the curtain as Raymonde enters hastily from the changing room. She slaps his face before recognizing the man is not her husband. Unabashed, Tournel seeks to take advantage of the situation. While Raymonde hesitates on whether she should accept, she inadvertently presses a button which turns their bed around through the wall while the bed in the next room revolves into theirs, a bed occupied by an old man, Baptistin, who complains of rheumatism. The revolving beds are meant to serve as a front in case police officers appear in the hotel rooms. Fearing the old man, Raymonde rushes out of the room and heads downstairs, then runs upstairs four steps at a time after seeing her husband arrive though disguised as a servant. She precipitously enters a room with an open door, occupied by a lusting Englishman named Rugby. She comes back out struggling to get away from him, intent on slapping his face which Tournel, trying to help her, receives in his place. Seeing Baptistin still in their room and hoping to rid themselves of him, Tournel presses the button, after which a servant named Poche is seen on the revolving bed, wearing the same costume as Raymonde's husband and closely resembling him in feature. In fear, Tournel cries out: "My friend, my friend, don't believe what you see." "Pity! Pity! Don't condemn until you hear me," Raymonde cries out. Both fall at his feet and beg to be beaten, but obtain no response. "Anything is better than that frightening calm," Raymonde declares. When Poche appears ready to forgive, Raymonde asks for a kiss, as does Turnel. Meanwhile, informed about the letter, Chandebise's nephew, Camille, arrives and asks for his usual room under the assumed name of Chandebise. Seeing Poche, he also mistakes him for Chandebise and, to avoid him, runs quickly inside the first room he sees, Rugby's again. To rid themselves of Baptistin a second time, Raymonde presses the bed button and this time beholds Camille on the revolving bed. Raymonde and Tournel run away from him, but are forced to run back up again after seeing Etienne, her servant, on the stairs, who warns her that Chandebise knows everything. Incensed at being invaded by a stranger, Rugby pushes Camille out of his room and hits him on the mouth. The blow causes him to lose sight of the speaking apparatus he needs to be understood. Etienne knocks and enters inside Rugby's room, where he discovers his wife in bed with an unknown man. Mistaking him for Chandebise, Etienne stops Poche in the corridor and complains about being a cuckold. Lucienne arrives on the scene, followed shortly after by Chandebise, who admits having shown her letter to Homenidès. They run downstairs but run back up again on seeing Homenidès with a revolver in his hand. Chandebise is pushed out of his room by Rugby and confronted with the hotel manager, Ferraillon, who, mistaking him for his servant, Poche, verbally and physically abuses him. After being pummeled, Chandebise sees his wife accompanied by Tournel. He angrily seizes him by the throat until Ferraillon comes back to berate him again as Turnel makes his escape. The worried Homenidès forces his way inside Camille's room and accidently turns the bed button. On the revolving bed, Lucienne and Poche appear, both disappearing after seeing the revolver in her husband's hand. Later, at Chandebise's house, Poche asks Raymonde whether he can see her husband. Still mistaking him for Chandebise, she, Tournel, and Lucienne all believe the man to be mad or drunk. Poche is taken away to sleep in Chandebise's bathrobe as Chandebise himself arrives, asking Tournel once more the reason why he found him with his wife at the hotel. Disgusted at these confusions, he chases them away. Ferraillon enters to give back Camille's speaking apparatus. Mistaking him again for Poche, Ferraillon heaps further abuses on him. Chandebise disappears only to find the threatening Homenidès, when once again he makes his escape. When Homenidès finds a copy of the letter among Raymonde's papers and asks her the meaning of this, the question is finally resolved by his wife. A stunned Chandebise returns to say he saw his own person in his bed while Ferraillon returns to berate him again until Raymonde reveals he is her husband, all this trouble because her husband's impotence had put a flea in her ear.

Sacha Guitry

[edit | edit source]

The most important figure in the 1915-1945 span of Boulevard theatre is Sacha Guitry (1885-1957), with comedy-dramas such as "Le nouveau testament" (The new testament, 1934) and "Deburau" (1918). "The new testament" concerns what happens when a man's coat is found with his testament in one pocket, so that he becomes falsely declared to be dead. "Deburau" concerns the life of Jean-Gaspard-Baptiste Deburau (1796-1846), a pantomime working under the stage-name of Baptiste.

In "Deburau", "the story of the play is a Pierrot story from beginning to end. What are the two experiences in reaction to which Pierrot shows that sentiment which is peculiarly his? Entirely sensual, yet airily tender, hopeless love, and the tragedy of old age...There is nothing in poor Pierrot’s philosophy to fight these ills which he feels so keenly. Still, he has one resource, namely indulgence in an exquisite, slightly mocking self-pity. His escape is, indeed, to make a beautiful little work of art out of that unattractive emotion which we usually handle so clumsily- self-pity...I do not believe a thorough Englishman can act Pierrot at all; he is a child of the Latin zone, born beyond the influence of Northern tenderness, though he in a different way is tender, and of Northern seriousness, though in his way Pierrot too is serious. The prime requisite of a Pierrot is complete absence of reserve and of all fear of emotion, and where, I ask you, will you find that, either in art or life, on this island? If this play, for it is a very pretty one, does not attract, it will be due chiefly to the flatness of the last act, which seems on the stage to drag and drag and then suddenly just stop. The part of Charles Deburau in this scene, Pierrot’s young son, is an exceedingly difficult one to play; he must suggest the timid eagerness yet truthless impatience of young talent which seizes hungrily its opportunity. We must be convinced that when he leaps on the stage he will inherit that very night his father’s fame. If we do not, the conflict of emotions in Pierrot himself will not seem moving, nor will the irony of the crier’s bawling to the public outside to come in and see a new Deburau as wonderful as the old, make touching the son’s sudden revulsion of emotion, when, feeling at last, like a stab right through him, absolute certainty he will inherit his father’s fame, he flings his arms round him, crying- the happy supplanter- 'No, no. It is not true, father. Why does he lie like that?'" (MacCarthy, 1940 pp 70-72).

"The new testament"

[edit | edit source]Time: 1934. Place: Paris, France.

Text at ?

After finding a new position for his secretary, John, a doctor, must find another one to replace her. His wife, Lucy, suggests Fernando, son to a friend of his, Adrian, a radiologist, but he hires instead Juliette, whom Lucy immediately detests to the extent of provoking her in the hope that she will lose her place. John is late to dinner at his house on a night when Adrian and his wife, Margaret, are invited. A messenger leaves behind a coat, inside which a worried Lucy discovers an envelope addressed to her husband's notary as well as his last will and testament. She faints. According to this new will, Lucy gets only one third of his fortune, the other parts going to Madeleine and Juliet Courtois, two women whom she has never heard of, but she guesses that Juliet is the woman her husband has just hired as secretary, the other being her mother. Lucy is all the more upset on reading the written date: 25 April 1934, thinking her husband probably committed suicide on this very day. In addition, the will also mentions "a son, who, without knowing it, avenges his father's honor," by which she discovers that her husband knew about her adulterous relation with Fernando. It is Margaret's turn to faint when her adultery with John from 25 years ago is mentioned. Unexpectedly, John himself enters amid the distraught group and finds his coat left by mistake at his tailor's, but without the envelope, hidden underneath Lucy's dress. The following morning, John learns from Margaret, veiled like a widow for the sake of secrecy, the entire story of last evening's events. Despite the awkwardness of the discovery, Margaret declares that their relation together was "the only agreeable moment of my existence". John does not reveal to her whether Juliet is his mistress, or else her daughter, neither does he reveal to Juliet who her father is, but she guesses it is he himself. Later, Lucy, joined again with their friends, sees the butler wearing John's coat, a sign which prompts her to think her husband has committed suicide. But once again he enters in great shape, revealing that he has decided to take part in a foreign delegation of doctors and to take Juliet along with him as his secretary. Lucy looks at Fernando, for them a good opportunity to continue their relation, she considering that to cheat in love "is to wish for happiness". Before going away, John lets her know that Juliet is indeed his daughter.

"Deburau"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1830s and 1840s. Place: Paris, France.

Text at http://www.archive.org/details/deburauacomedya00grangoog https://archive.org/details/cu31924027399421 https://archive.org/details/deburauacomedya01grangoog

Jean-Gaspard Deburau, a successful pantomime at the Funambules Theatre under the stage name of Baptiste, receives a bouquet of carnations sent by one of his fans. A lady arrives to lead him away from the theatre, but, after he takes out his wife's picture, she abandons that plan. A second woman arrives, roped with diamonds and a camelia on her belt, Marie Duplessis, a noted courtesan. To her, he does not show his wife's picture, but she is not the one who sent him flowers. It is the employee at the cashier's desk, pining for him uselessly. Deburau is taken with Marie. "I adored the sun," he says, "I like today the rain as well as the sun." Deburau is constrained in an unhappy marriage and, were that possible, wishes to marry Marie instead, his lady of the camellias. She answers yes because it is impossible. After he leaves, Marie admits to a conjurer friend that she loved Deburau only for a day or so. His wife having left him, he joyfully returns with Charles, his ten-year-old son, a dog, and a bird-cage at the very moment Marie is already in the arms of a new-found love, Armand Duval, yet he expects to see her again. Seven years later, Deburau is still expecting Marie to come back. When Charles tells him he would like to become a mime like him, he disagrees with that choice, emphasizing the difficulty inherent in making a living out of that art, encouraging him instead to become an actor at worst. Surprisingly, Marie returns, the result of a friend's intervention on his behalf since Deburau leads such a hermit's life and appears to be sick. When he discovers she came only to look after his health, he loses interest in her. A doctor arrives to encourage him to take up various hobbies. Reading? "I prefer death without words," he retorts. At last, he decides to return to the stage, but, older now, is unsuccessful. As he is about to speak to his disgruntled public, he finds himself unable to. He kisses them goodbye instead. The curtain closes on him sadly and slowly. The last curtain falls on him like the guillotine, "for a soldier, it is the flag that one throws on his coffin," he declares. The theatre director must now replace him with a journeyman, but Deburau has a better idea: put Charles on, whom he starts to coache on the spot.

Marcel Achard

[edit | edit source]

Marcel Achard (1899-1974) competed with Guitry at his best with satires on domestic confidence with "Colinette" (1942) and on boyhood friendship with "Patate" (Potato, 1957).

"In 'Potato', the triangle becomes a pentagon involving two married couples and an adopted orphan. The hero is a disenchanted inventor called Rollo who wastes his time alternately hating a successful rival, Carradine, and borrowing large sums of money from him. Rollo's 18-year old adopted daughter, Alexa, represents modern youth, although she claims that 'it is old-fashioned to be modern'. Her language would shock American parents into some measure of protest or discipline, and, while her actions speak softer than her words, she is 'quite a number', as Carradine's wife, Véronique, says. In describing how she turned down a proposition, Alexa says: 'Two propositions a week, that's my average...the last one was last night...not very interesting...done entirely by gestures...and answered, too: my hand on his face. Then he called me a little whore...This gave me the chance to reply: 'thanks for telling me. Now I don't have to prove it.' Beneath this wise-guy attitude, Alexa is an unhappy girl who longs for the marital security that her adopted parents enjoy. Her love affair with Rollo's old friend-foe, Carradine, is discovered when her adopted mother finds some highly compromising love letters. Rollo thinks that they are intended for his wife, and Alexa is forced to confess that they are her own, refusing, however, to name her partner. The irascible 'Patate'- a nickname given Rollo by Carradine, meaning sucker, fall guy, jerk- is determined to find out; the suspense, in shaggy-dog story fashion, leads us to the discovery and promptly bypasses it. Rollo, after elaborate speculations, comes to the idiotic conclusion that his daughter's lover must be the family doctor. Finally he realizes that it is his old friend, Carradine. Characteristically, Achard has Rollo recognize the letter 'Z' which has figured so prominently and humiliatingly in his own search for cash, in the word 'payez' on Carradine's checks endorsed to Rollo. Revenge is sweet. Rollo is almost sick with joy as he anticipates all the humiliations he will inflict on Carradine. But now comes the play's final irony: Rollo can't go through with it. Why not? Simply because he is a nice guy...'Patate' has the elements of a detective story. When, in his apartment, Rollo surprises Carradine who was planning to meet little Alexa there, the humor of the situation is caused by Carradine's surprise and embarrassment. We're laughing with Rollo. But when, a few minutes later, Carradine calmly chooses suicide rather than shame, it is Rollo who becomes funny. As a result of the sudden switch, his revenge has turned sour. Yet Achard never lets his heroes down: their sympathetic quality is established in the first scene, and it is important that the actor know this trait, lest his characterization become unclear" (Mankin, 1959 pp 35-36).

"Colinette"

[edit | edit source]Time: 1940s. Place: Paris and suburb, France.

Text at ?

Wallowing in a Turkish bath, Rivière and Passerose compare how each is mistreated by their respective wives. Rivière complains that his wife pours water on his stomach while he sleeps, cares only to walk when his boots are new, and prevents him from being sexually aroused. Passerose complains that his wife exposes him to what he loves so often that it eventually disgusts him and that she has cuckolded him. Rivière retorts that he is a cuckold, too. Neither is impressed with the fellows who have cuckolded them. Passerose and his wife agreed not to let her lover know that her husband knows, while Rivière’s wife and lover are unaware he knows. A third occupant, Lionel Charmaine, declares that cuckoldry is always the cuckold’s fault, not the woman’s. A fourth customer, Polo, is more skeptical about women’s virtues. More particularly, Lionel boasts about the virtues of his wife, Colinette. “If anyone is sure not to be a cuckold, it is certainly me,” he asserts. Rivière is enraged about such confidence. He bets 10,000 francs that Colinette has or will cuckold Lionel and proposes the experienced Canrobert to do the job. Passerose accepts the bet. But since Canrobert is unavailable, they choose instead Polo, now remorseful for his previous opinions against women. Unaware of the bet, Lionel accepts Rivière’s suggestion of inviting Polo over at his home. During that very first evening, within five minutes, Lionel discovers his wife in Polo’s arms. Nonplussed and to Polo’s surprise, she declares that her relation with her husband has ended and that she intends leaving with Polo immediately, although she admits that she knows little about him. An irate Lionel points out that Polo’s salary is lower than Colinette’s pocket-money. Unperturbed, she is satisfied that Polo has enough to pay for a taxi. She points out that their guest, Armande, loves her husband and tried to convince her to leave him. Armande angrily denies it and leaves immediately, followed by Lionel after expressing vague threats. When they hear the door slowly re-open, both think that it is Lionel. “Kiss me quickly,” she suggests. “And if he kills us, good!” But it is only the triumphant Rivière followed by the dejected and half-believing Passerose, who lets slip the matter of the 10,000 francs to the uncomprehending lovers. Having misunderstood the two friends, Armande returns to reveal that Polo made love to her only to win some money on a bet. Despite the two friends’ denial of Polo’s involvement, Colinette believes Armande. “The romance is over, Polo” she declares. “I can no longer believe you.” When a haggard Lionel returns, Colinette remains still without even turning to look at him. “Put down your fire-arm, Lionel,” she says. “You come too late. There is nothing here to kill.” As a result, Rivière, Passerose, and Armande take turns staying at Polo’s apartment to console him, though since being complimented for his handsome feet, Passerose has gotten in the habit of walking barefoot, caught cold, and can no longer speak. Polo has shown neither sexual interest for Armande nor for her invited guest. “He yawns when I take my clothes off,” she informs them. Before his worried friends, a dejected Polo prepares his luggage for a vaguely planned trip while talking aloud to an invisible Colinette. When the real Colinette shows up, they recognize to have shared the same dreams together though separately. She left her husband six weeks ago, who found her yesterday and has since followed her everywhere. Recognizing Polo’s love for her, she spreads disorder in his apartment as Polo leaves in the next room until Lionel knocks at the door, at which time she pretends to have lived with Polo all this time while re-arranging his apartment while pregnant. Lionel hands her a document stating that she agrees to renounce every material advantage of his fortune and confesses that he knew all along about the bet, regretting his over-confidence.

"Potato"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1950s. Place: France.

Text at ?

When Leon asks his old school-friend, Noel, for a large loan, he refuses but then accepts to buy off his idea of being able to predict the future based on the tossing of dice. Meanwhile, Leon's wife, Edith, is shocked to discover that their adopted 12-year-old daughter, Alexa, is having an affair with a married man. When Edith asks who the man is, Alexa retorts that "Authority comes too late, poor dear." When Edith opines that Alexa may not find happiness in such a relation, she retorts that "happiness is perhaps not indispensable." The mother insists that Alexa will be unable to have a life with him. "My life!" Alexa exclaims. "You know well that we, the young, have no future." Mother and daughter are unable to keep the adulterer's letters away from Leon, who believes them to have been written to his own wife. "I adore to see you lift your skirt to prove you are right," he reads aloud in a shocked voice. After several series of confusions, Alexa finally reveals that the letters apply to her. And after considerable effort, Leon discovers who the adulterer is no other than Noel, on whom he plans to avenge himself for a lifetime of torment the man caused him, including being mocked as a school-boy for looking like a potato. Edith is revolted at this plan. Nevertheless, when alone with Noel, Leon threatens to reveal the content of the letters to his wife, Veronica, who in the event of a divorce would make him penniless. Leon jubilates at the thought, considering himself "a potato that is choking you". But Noel surprises Leon by announcing that he intends to commit suicide, since his wife possesses letters proving the existence of illegal financial transactions on his part. Leon is forced to desist. After learning of her lover's situation, Alexa abandons him, preferring to "put a boy between herself and the man". They burn the letters. Despite this move, Veronica guesses the truth, but nevertheless chooses to remain with her husband.

Tristan Bernard

[edit | edit source]

Other comic playwrights rising to the fore include Tristan Bernard (1866-1947) for his satire on boss-employee relations, "Le petit café" (The little coffee-house, 1911). Bernard also wrote "The unknown dancer" (1909) and "In perfect accord" (1911). In "The unknown dancer", during the course of a masked ball, Henry, a poor salesman working at a steel company, meets Bertha, a rich heiress. They become mutually attracted to each other. To impress her father, he is convinced by his friend, Barthazard, to exaggerate the amount of his salary but then develops scruples about having to add continual lies. He writes a letter to the father admitting his fault and eventually obtains a position as a salesman at a furniture store. Bertha's friend, Louise, learns of this and arranges to enter with her and her new fiancée to the store, where Bertha becomes convinced that Henry loves her for herself, not her money. Concerning "In perfect accord", Achilles and Bertha are married without engaging in sexual intercourse since he found out that she has a lover, Maurice. One day, Bertha and Maurice are caught kissing each other by Achilles' blabbermouth secretary. To placate public opinion, they agree to divorce so that Bertha can marry Maurice. Their perfect accord is troubled when Achilles progressively feels unwanted by her. To assure him of their mutual friendship, she and he become lovers again without telling Maurice and so all three return in perfect agreement with each other. She feels like a queen. "I have a serious steward who directs me," she boats to Achilles, "and a worried page whom I dominate.”

"If one were to select a single piece of Bernard's as representative, ['The little coffee-house'] would be entitled to first consideration...There are capital episodes, such as Albert's preparation to fight a duel, abandoned when his second, a general, discovers his low social station; or his defeat, by giving a handsome pourboire to a coachman, of the contention of a union official regarding the poverty of waiters. Here, as everywhere, Tristan Bernard shows freshness of invention, an eye for realistic detail, a love of the logical reductio ad absurdum, high spirits that make the impossible credible, and a power of revealing character in single strokes. His dialogue is graceful and witty, and his fund of good nature is inexhaustible" (Chandler, 1920 pp 171-172).

"The little coffee-house"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1910s. Place: France.

Text at ?

Albert grew up as a servant on the castle grounds of the count of Caspion, who suddenly died while travelling around the globe. With no money left to pay for his upkeep, Albert was let go and found a position as a waiter in a small cafe. His girlfriend, Edwige, a popular singer, prefers for the moment not to marry him out of fear that he would choose to live at her expense. One day, Albert's boss, Philibert, learns from his friend, Bigredon, that the count of Caspion's will has been found, stipulating that a huge sum of money (800,000 francs) is left to Albert. Bigredon suggests that he seize the opportunity by binding Albert to a 20-year contract at 5,000 francs per year with a codicil stating that whoever breaks the contract will be forced to pay to the other party 200,000 francs, probably Albert, likely to be unwilling to remain at work after learning of his inheritance. Philibert pretends to be reluctant but then accepts. As anticipated, Albert signs the contract. But after being informed of his inheritance, he unexpectedly refuses to hand over the 200,000 francs. Instead, he tries to provoke his boss into dismissing him by refusing to obey his orders. However, Albert's colleague, a dishwasher, learns that Philibert will bring with him a court-servant as a witness to his employee's irresponsible behavior and so have him dismissed by legal means. On being told of Philibert's plan, Albert resumes his polite and docile demeanor. Now rich, whenever his work-day is over, he often treats his other girl-friend, Bérangère, a courtesan, to expensive restaurants. One evening, Edwige is hired as an entertainer in one such restaurant. Unaware of his new-found wealth, she is startled to discover Albert's presence. To avoid her finding about his wealth and Bérangère's existence, he pretends to have found a second job as a waiter there. Likewise, Bérangère is startled and then angry at his refusal to sit with her and her friends at their table. Eventually, Edwige sees Bérangère caressing her lover's hair, and so the two women fight. When a customer, Gastonnet, gets in Edwige's way, she pretends to have been stuck by him. "If you do not slap him," she tells Albert, "you are the greatest of louts." "Sir, consider yourself slapped," Albert declares. They agree to fight in a duel but, before that can eb arranged, Albert is arrested for disturbing the peace. After being released from jail, he heads back at the cafe, where the head of the waiter's union, intending to show the woes of that profession to a journalist, is unpleasantly surprised to hear about Albert's expensive habits, leaving in disgust. A general is summoned by Gastonnet's friend to organize the duel, but after learning that Albert is a mere waiter, he too leaves in disgust. Finally, Philibert is disgusted at the entire situation and dismisses Albert. However, to his surprise, Albert once more refuses to go after discovering that Philibert's daughter loves him. The father approves.

Jules Romains

[edit | edit source]

Jules Romains (1885-1972) showed excellence in the boulevard genre thanks to a medical satire, "Knock" (1923).

In "Knock", "the humor of the plot is enhanced by the witty repartee” (Troiano, 1986 p 1553). Dr Knock’s “plan for conquest is clearly of long standing and carefully organised. He assiduously acquaints himself with the incomes of his clients. Patients are ruthlessly stripped of their defences, beginning with the flimsy mantle of insouciance which has protected them from worrying about their health...Knock proffers big words, not for the sake of the cure, but for the rather more pertinent issue of reinforcing his authority...Knock astounds his predecessor with his figures for the last three months, and not just the consultation rates: he knows the incomes of every household in the canton. But it’s not their money he’s after, he assures Parpalaid: he has brought people to medicine, he has given their lives a medical meaning...Knock is acting not in his own good, he tells Parpalaid, nor even that of his patients, but in the interests of that third: medicine. Parpalaid is struck dumb, bereft of argument. There can be only one possible conclusion: soon the old doctor, who has already had to suffer the ignominy of his less than rapturous welcome by the hotel/hospital staff, and who would seem the person best armed through his culture and experience to recognise Knock for what he is, an agent of the great lie, and thereby resist his blandishments, is being invited by his successor to take a rest cure himself. Knock’s medicalisation of the canton is complete...Knock has found a way to deflect hubris. By deflecting it from himself, he obliges Nemesis to visit those who take him at his word” (Bamforth, 2002 pp 15-17).

“Doctor Knock, the principal protagonist, changes the entire existence of Saint-Maurice with the creation of an unanimistic mind among the villagers. In this respect the comedy- in which there is more of the serious than of the comic- has a sociological as well as a literary interest” (Delano, 1928 p 494). “A medical man by profession, [Knock] is a dictator by vocation...Knock’s approach to the situation, which had at the outset been purely realistic, has become almost that of the mystic, a high priest of medicine. Closely interwoven into the theme of unanimist creation is of the gullibility of the masses, and in showing Knock as being on the point of falling a victim to his own propaganda, Romains’ comedy gives food for thought” (Knowles, 1967 pp 78-79).

“The main theme is really the power of suggestion...Looked at dispassionately, the implications of Knock are serious, and critics have talked of Romains’ methods as leading to political dictatorship if applied in that sphere...Comedy of character is combined with comedy of situation, comedy of language- the extremely witty replies- and with comedy of gesture on stage, to form one of the most amusing and dramatically effective plays of our age” (Boak, 1974 pp 76-77).

"Knock"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1920s. Place: France.

Text at ?

Dr Parpalaid leaves a small town to practice medicine in a larger city, handing over his patients to Dr Knock, dismayed to learn how rarely townspeople consult their physician. He first presented this viewpoint in his medical thesis, emphasizing that "healthy people are the sick who ignore their true state". He began to practice medicine without the required degree as a ship doctor and, soon successful, is determined to succeed here as well. His first new idea is to advertise free consultations once a week by the town crier, who mentions in passing how his throat bothers him. Dr Knock asks him to specify whether it is a tickling sensation or a scratching sensation and further asks even more perplexing questions, so that the patient wonders whether he should go to bed at once, but the doctor assures him that he can wait till evening. He asks to see a schoolteacher and is astonished to learn that he and Dr Parpalaid were not in the habit of warning people about the multitudinous dangers inherent in not consulting their physiscian regularly. Knock explains the many functions that can go wrong inside the body and is confident that with the teacher's help the townspeople will be unable to sleep at night. Knock then informs the local pharmacist that his revenues are likely to increase. The pharmacist is dubious, since, to require his services, a man must first become sick, an old-fashioned viewpoint, according to Knock. "For my part," Knock says, "I know only people more or less stricken with illnesses more or less plentiful progressing at a more or less rapid rate." His first patient is a woman complaining of constipation. After briefly examining her and although she does not remember it, he concludes that she fell from a ladder "about three meters and a half high, against a wall". "You fell backwards," he specifies, "luckily on the left buttock." He recommends no solid food for one entire week, warning her that the treatment is likely to be costly. His second patient is a woman complaining of insomnia. He convinces her of the seriousness of her condition, explaining in detail the many malformations of the nervous system that can occur in such cases until she is ready to submit to any treatment if only he can save her. Thus, Knock's private practice, to the pharmacist's content, grows enormously. He waxes lyrical in contemplating the lights in houses at night of his many anxious patients. "The canton cedes her place to a sort of firmament, of which I am the continual creator," he enthuses. Learning of this surprising turn of events, Dr Parpalaid offers him to exchange his present practice with the old one, but Knock refuses, although fully cognizant that his talents must eventually reach a broader stage. A tired-looking Parpalaid wonders whether Knock was joking in insinuating that he appears to need a day of rest. Knock responds that they can see about that later, this said in such a tone that Parpalaid begins to worry about his present state of health.

Jacques Deval

[edit | edit source]

Jacques Deval (1890-1972) excelled in an immigration satire, "Tovaritch" (Tovarich, 1933) along with a worthwhile boulevard drama, “Il était un gare” (There was a train station, 1953).

In "Tovarich", this sudden confrontation of the Russia of yesterday and the Russia of today, coming after three acts of fantasy and scintillating dialogue, is disconcerting, but Deval’s skill as a dramatist carries it through” (Knowles, 1967 p 285).

"Tovarich"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1930s. Place: Paris, France.

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.151773/page/n13

Mikail and Tatania, escaped prince and princess respectively in the aftermatch of the 1917 Russian revolution, have difficulty in meeting ends meet in a Paris hotel. The former prince refuses to yield an immense sum of money given to him by the former czar to the heir to the throne. "What a crowned czar gave me, I will return to a crowned czar," he declares. The couple are driven to accept employment as mere servants in the house of a banker, Charles Arbeziat, and his wife, Fernande. To Charles, the ideal servant is characterized by "punctuality, silence, deference." To his surprise, he is very pleased at the kind of service Mikail renders, but is taken aback at his manner of thanks: a kiss on the shoulder in the old Russian manner. To help her mistress who had bought for herself some expensive hats, Tatiana sends away the employee waiting for payment. "I can assure, madam, by St Peter and St Paul, that you will see no bill for the next three months," she promises. But her employer will have none of that. The entire household is pleased with their new servants, including George, their son, who likes to fence with Mikail, as well as Helen, their daughter, who learns Russian songs from Tatiana. But when George starts to flirt with Tatiana, she rejects him. One evening, the Arbeziats invite over to dinner important men involved in an oil deal with Russia, including the people's commissar for petrolium, Dmitri, who, during the revolution, tortured Mikail and raped Tatiana when they were held in custody. One of the guests, Lady Kerrigan, recognizes Tatiana as the former czar's niece and a bank official recognizes Mikail, to the amazement of the Arbeziats. Dmitri also recognizes Mikail and coolly asks for a light for his cigarette. To Tatiana he asks for a glass of water. After he drinks from the glass, she casually mentions that she spit on it. As a result of this discovery and to their grief, Mikail and Tatiana learn that the Arbeziats will no longer keep them in their employ. At the end of the evening, Dmitri enters the kitchen to tell the two servants that he refuses to finalize the deal, thereby preventing French, British, and American influences on Russian soil. Instead, he requests Mikail to deliver the czar's money. Otherwise, a great famine is likely to ensue. Reluctantly, Mikail and Tatiana yield. Dmitri thanks Tatiana by kissing her reverently on the shoulder.

"There was a train station"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1950s. Place: The fictionalized town of Couvize, France.

Text at ?

Because of a lack in passenger traffic, the stationmaster, Bernard, informs Néomie, owner of a coffee house in the train station, that two fewer trains will soon stop at their location. Because he had to pay to prevent his son from being taken to prison for five years, Bernard has refused to talk to him for the last five years. Néomie’s two employees, Yvonne and Odile (nicknamed Snow White because of her innocent outlook in life), expect one day to quit their jobs, the former by engaging in a relationship with an employee of the mail train and the latter always stuffing her suitcase with assorted items in expectation of leaving suddenly with some interesting traveller. Due to technical difficulties, passengers of a train heading for Paris and another for Marseille are forced to stop over at the station, from the latter of which emerge George, recently been released from prison, along with a recent acquaintance of his who also admits to being released from prison, in reality Police Inspector Louvet, tailing him to prevent a robbery planned by that young man. While Inspector Louvet reports by telephone the present situation to his superior, a woman sits impatiently beside him. As soon as he is finished with his report and in view of her worried expression, he facilitates the speed of her call by transmitting it via his own police number whereby she reaches her lover’s servant, only to learn that his master intends to cut off all relations with her in favor of Gladys, a rich American woman. As Néomie approaches to serve at a table, she is stunned to discover her lover from 30 years ago, now a famous classical pianist, Eric Igunesco, but is disheartened to discover that the man fails to recognize her face. At another table, a 17-year-old girl, Helen, entertains hopes of a movie career, encouraged by her agent, Mrs Salviatti, on their way to meet a supposedly important executive. At yet another table, Yvonne is intrigued by the fake jewelry deployed by a travelling salesman, Charles. Long irritated by Snow White’s dream of leaving one day with an amorous traveller, she proposes to use Charles as a fake lover. Meanwhile, Louvet recognizes Mrs Salviatti as a procuress, but, lacking proof of her intentions, leaves her for the moment. A recently married couple, John and Renée, squabble over the lottery win that led to their honeymoon, the result of a man bequeathing money to any couple willing to marry and travel by the same honeymoon route he was happy to undergo in his youth. Despite this fortunate occurrence, John is irate at being forced to lug around the man’s ashes in a ciborium, so that he heads out to look for a small box to put them in despite his wife’s warning that she is determined to return to Paris if ever he presumes to touch the ashes. Wanda is back at the phone with a second plea, this time directed at her lover’s mother for the purpose of interfering with her son’s intention of leaving her, but the plan fails. John finds Helen to his taste and flirts, pretending to be on the way of retrieving an important sum of money as an heir to his dead uncle. The flirtation leads to nothing, unlike Charles’ attempt at seducing Snow White into admiring the jewels he says he bought for the maharaja he works for. Charles further explains that he is ordered to bring along a girl destined for his harem. A man enters and sits at the same table as a newly arrived nun, Sister Angelica, on which he spreads out newspaper clippings. While Eric listlessly rummages about on the counter where a cutting machine lies, Néomie cries out and lurches forward to prevent the danger to his fingers, deeply cutting her own thumb instead. Sister Angelica rushes over to cover Néomie’s damaged hand with a bandage, after which Néomie heads for the pharmacy. While walking back to her seat, the nun notices her companion’s tormented expression. The man explains that he is the state executioner, convinced that the prisoner he is about to execute in Paris is innocent. “There is no danger for the eyes of prayer,” the nun declares encouragingly. Having found the box, John proposes to challenge his wife to a game of electric billiards, which she accepts on the condition that if he wins, both will return to Paris. In her last desperate attempt, Wanda calls up Gladys at her hotel, who promptly makes love to their mutual lover while holding on to the phone. Louvet returns to Mrs Salviatti to reveal the name of the movie executive she and Helen plan to meet, a pornographer expert in blackmailing girls into making films for him. She pretends never to have heard of him. Sister Angelica recommends that the executioner think of his prisoner instead of himself. “Is it nothing for the condemned to witness a last look of compassion, the supreme respects of charity rather than a rude and glacial face?,” she asks. The executioner becomes reconciled. On her way out, the sister advances to watch the billiard game, so that Renée yields her place to her. As a result, the board lights up and, to John’s astonishment, Renée wins the game. George attempts to convince Helen to follow him while she attempts to convince him to do the same. Both fail. After failing in her own attempts to win her lover back, Wanda seeks revenge by calling up the brother of a man sent to jail for cocaine possession after being denounced to the police by Gladys. Néomie returns with the news that a doctor discovered a cut tendon, ending her piano playing days, news hidden from Eric, who, quite contrite, leaves a generous cheque for her as compensation. “In five years, in ten, I would recognize you among a thousand, among ten thousand, anywhere,” he swears on his way out. “I have confidence in your memory,” she replies. As Bernard announces all aboard, he is stunned to discover that the executioner is his son. Yvonne returns from her meeting with the postal man in a woebegone state and the front of her dress torn. Preparing to close up, Néomie and Yvonne discover Wanda slumped over her table, dead after poisoning herself. Snow White likewise returns in a woebegone state after Charles, pitying her innocence, prevented her from boarding the train at the last minute. Yvonne’s case is worse, since after the postal man took her inside the train, he and two others gang-raped her. But Helen’s case improves when after boarding George’s train without finding him inside, she returned to the station to find him likewise back to the station after failing to find her in hers.

Maurice Hennequin and Pierre Veber

[edit | edit source]

Maurice Hennequin (1863-1926), of Belgian origin, and Pierre Veber (1869-1942), of French origin, teamed up for several plays, none worthier and nearest de style of Feydeau than "Vous n'avez rien à déclarer?" (You have nothing to declare?, 1906). Hennequin also wrote with Albin Valabrègue (1853-1937) "Vacations away from marriage" (1887) in which Paul flirts with Edith until her uncle Poulsom appears who expects a marriage offer for his niece. To avoid that violent man, Paul prepares to leave but is prevented by his wife and mother-in-law at the hotel. Hennequin also wrote with Paul Bilhaud (1854-1933) "Nelly Rozier" (1901) and "The Bolero family" (1903). In "Nelly Rozier", Albert, growing tired of his adulterous relation with Nelly whose husband had abandoned her, pretends to be in danger of his life to a jealous wife. However, Nelly discovers the lie and avenges herself by obtaining employment as a servant to his wife, Clemence, to prevent his entering into another adulterous relation with Valentine. In "The Bolero family", Adolph has an adulterous relation with Consuelo Bolero, a star in variety shows, who, together with her family, manipulates him into giving her a great deal of money while offering little in return.

"You have nothing to declare?"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1900s. Place: Paris, France.

Text at ?

While Samuel Dupont, a magistrate, waits for the return of his daughter, Paulette, from her honeymoon with her husband, Robert de Trivelin, a stranger, Frontignac, asks to see his wife. On seeing Samuel's wife, Adelaide, Frontignac abruptly turns to leave until stopped by Sam who wants to know which woman he is looking for. A camel mechant in Algeria, Frontignac explains that, having recently met a woman he wishes to marry, he is looking for his wife who abandoned him, prior to initiating divorce proceedings against her. Sam informs Adelaide he is expecting to receive a painting he bought in charity from a one-armed old woman, in actuality his 28-year old mistress, Zézé, who, unknown to him, is Frontignac's wife. When Paulette and Robert arrive, the Duponts discover that he has failed to make love to his wife during the entire trip. Their shame-faced son-in-law explains that when he began to make love to Paulette in the sleeping compartment of a train, he was interrupted by a customs agent who asked him: “You have nothing to declare?” since which time he has been unable to have an erection. Showing no sympathy for his problem, the irate Duponts threaten to force him to divorce their daughter unless he accomplishes the expected feat within three days. To help in Robert's plight, Sam’s friend, Couzan, suggests that a visit to a prostitute might solve the problem. Before going to that extreme, Robert cuddles with his wife. However, hearing of his plight, a rejected old suitor of hers, La Baule, interrupts the couple by crying out outside the bedroom door “You have nothing to declare?,” a call sufficient to discourage the unhappy husband. As a result, Robert heads for a whore's apartment, by chance Zézé's, but is followed by the jealous La Baule, another of her clients. While the hopeful husband is putting on his pyjamas, La Baule pays Zézé to hold him off for a day. She agrees and hides Robert’s clothes to prevent him from leaving. However, she is unable to resist making love to Robert, but when at the point of succumbing, La Baule cries out: “You have nothing to declare?,” which once again discourages the astonished Robert, who thinks he has begun to hallucinate. Nevertheless, he finally achieves his purpose but is forced to hide after seeing La Baule enter with the prim Adelaide to present her with evidence that her son-in-law’s impotence is caused by frequent debaucheries. Instead, Adelaide encounters her husband, hiding to discover Zézé’s lover whom he has heard about. To Robert’s amusement, Sam starts to strangle La Baule until the latter proposes that the husband explain his presence at Zézé’s to his wife for the same reason he accompanied her: exposing her son-in-law’s debaucheries. As an added precaution, La Baule takes from Zézé’s servant Robert’s clothes and heads for the police station to accuse him as the local rapist the police have been looking for. To replace his clothes, the cornered Robert calls out from the window to a passing stranger and, once inside, threatens to shoot him with a false forearm unless he yields his clothes. The passing stranger, by chance Frontignac, feels forced to accept. On leaving, Robert promises to return his clothes as Sam re-enters to confront Robert. To his astonishment, Sam discovers Frontignac instead, who plays him the same trick Robert did. When Zézé re-enters, she encounters a husband overjoyed at finding her at last as the police arrive to arrest the accused rapist, seemingly the almost naked Sam unable to make himself heard. Meanwhile, La Baule presents Adelaide with Robert’s clothes as evidence of her son-in-law’s proclivity towards debaucheries and, moreover, informs her that he has accused him of being a rapist. However, Robert arrives, sees his clothes spread out, and goes out with them as Frontignac enters with Sam’s clothes. After Frontignac leaves, La Baule presents Paulette with the clothes, but she immediately discovers that they are not her husband’s while Adelaide recognizes them as her own husband’s. In horror, La Baule rushes out after inferring that his future father-in-law, not Robert, was arrested for rape. When Sam after displeasing adventures is able to return home in a policeman’s outfit as replacement of his own, he is informed by Couzan how ill La Baule has served him. Robert re-enters, puts down Frontignac’s clothes, and attempts to make love to his wife, who, disgruntled at these events, locks herself inside her room. Meanwhile, the Duponts’ servant has discovered Sam’s police uniform under his wife’s bed. In danger of being accused of infidelity by his wife, Sam seizes the opportunity by accusing her of sleeping with a policeman. However, he becomes distraught when Frontignac re-enters to ask him to serve as witness to his wife’s infidelities. Although Robert is also in a position to reveal his relation with Zézé, Sam continues to refuse him as his son-in-law, as he does Gontran as future husband to his younger daughter when the latter presents him with a certificate from Zézé acknowledging his capabilities as a lover. Although Sam requested such an attestation to protect his daughter, he now refuses him by pretending that this was merely a test of the suitor’s fidelity. He plans to use this attestation to free him from Frontignac’s request but feels all the more cornered when Gontran also reveals he knows about his relation with Zézé. He finally submits to both after discovering that La Baule is another of Zézé’s clients and hands over to Frontignac a signed photograph she sent to the still rejected suitor.

Gaston de Caillavet and Robert de Flers

[edit | edit source]

Gaston Arman de Caillavet (1869-1915), Robert de Flers (1872-1927), and Emmanuel Arène (1856-1908) combined their talents in the political satire, "Le roi" (The king, 1908).

"'Le Roi' is the most uproarious of the Flers-Caillavet satires. Imagine, they tell us, the land of the Marseillaise turned topsy-turvy by the arrival of a royal personage! Imagine that personage a boulevardier among boulevardiers. King Manoel of Portugal must have been the original staunch socialist, making love to his wife, and turning the President and his Cabinet into a ridiculous pack of children! Paris is his playground. Received everywhere with acclamations and honor, no wonder he exults and waxes enthusiastic, crying 'How I love France!'...The daring of the plot, the breezy, ample, esprit 'gaulois' are far enough from the quiet sentiment of 'L'Amour veille' and 'L'Eventail'. The authors have entered a new field, in which they are destined to remain the masters, and win further laurels. The occasional vulgarity of 'Le Roi' is perhaps necessary, owing to the theme. To Anglo-Saxon minds there appears no excuse for many scenes in which sensuality per se is exploited for purely comic effect" (Clark, 1916 pp 189-193). "Delicious in its humor is the scene in which, discovering his Therèse and the king together, [Emile] is ready to roar in wrath, but, bit by bit, modifies the tone in which he exclaims 'Sire!' until he fairly purrs" (Chandler, 1920 pp 185-186).

"The king"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1900s. Place: Paris, France

Text at ?

Emile Bourdier, industrialist, mayor, and socialist member in the House of Commons, expects to be invited to a hunting trip organized by the marquis of Charamande, one of the hosts during King John IV of Serdania's visit in France, but he is not. He is disappointed at that and also because the marquis refuses to marry his son, Count Serin, to his daughter, Suzette. To avenge himself, Emile attempts to seduce the marquis' mistress, Theresa, an actress. After obtaining a rendez-vous with her, he is so overjoyed that he rushes into the next room to kiss his wife, Martha. In Theresa's boudoir, Blond, in charge of the king's security, enters disguised as a hairdresser to announce his master's imminent visit. Having slept with Theresa eight years ago, the king intends to renew that pleasant experience. Despite Blond's interference, Emile finds her in bed with the king. To mitigate her friend's anger, Theresa announces that the king intends to hunt on his castle grounds, not the marquis'. Overjoyed, the socialist politician kisses the king's hand. At Emile's residence, Martha is anxious about the king's reception and in particular asks Theresa's advice about how to salute his majesty. "One must sense deference at the calf but dignity at the torso," Theresa recommends. As Theresa prepares to leave, Martha insists on having her stay, to Emile's disgust. After the ceremonial duties are over and everyone has gone to bed, the king unexpectedly encounters Martha late at night. Eight years ago while he was parading down a street, she threw at him an apple turnover instead of flowers and hit him in the eye with it. He pardoned this excessive show of enthusiasm by sleeping with her. He does so a second time in her own home. The next morning, Emile discovers his wife in bed with the king. To appease his wrath, Theresa proposes to a round of politicians that they give her husband a new political appointment. They agree in conferring him a minister's post. In gratitude to her cleverness, the king signs a commercial agreement between their two countries, at which Emile beams with pride amid his colleagues as the new minister.

Louis Verneuil

[edit | edit source]

Husband and wife attempts at adultery are handled by "Ma cousine de Varsovie" (My cousin from Warsaw, 1923) as deftly described by Louis Verneuil (1893-1952).

“Verneuil has consistently turned aside from the experimental thea-ter, not for lack of ideas or creative vitality, but because, in the true spirit of Molière, he deliberately aims to please all spectators...His style is elegant and rings true and his dramatic flair is faultless. The combination gives us a series of varied plays, comedy, satire, opera, whimsy, almost all sure to succeed” (Kurz, 1942 p 229).

"My cousin from Warsaw"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1920s. Place: Saumur, France.

Text at ?

After suffering a stroke, Archie Burel retires from banking to lead a quieter life as a novelist. Nevertheless, he complains to his wife, Lucienne, about the frequent visits of his next-door neighbor though long-time friend, Hubert, a painter specializing in sunsets. Likewise, being Lucienne’s lover, Hubert complains about the constant presence of her husband. Nevertheless, she refuses to consider a divorce in view of Archie’s medical condition. Their talk is interrupted by the sudden arrival of Lucienne’s cousin, Sonia, a rich widow of Russian descent, on her way to Madrid with her chauffeur and an English lover. Moreover, Sonia announces that she is to marry the king’s cousin, presently in prison for attempting to lead a revolution against the king. From the looks of Lucienne and Hubert standing together, she guesses that the two are lovers. To spend more time alone with her lover, Lucienne proposes that Sonia seduce her husband. At first hesitant, Sonia eventualy accepts in view of Lucienne’s past help in preventing her murder by a Belgian duke by sleeping with him herself. Likewise, to spend more time alone with his wife, Archie proposes that Sonia seduce Hubert. She promises to think it over. Two days later, noticing that Archie has begun to feel amorous towards her, Sonia reminds him of his plan regarding Hubert, all the more readily because she prefers the latter as a potential lover. Hubert is easily seduced despite being troubled by Sonia’s confession that she was directed towards him by Archie, who, suddenly entering the room, interrupts their kiss and shows signs of increasing jealousy towards his friend regarding both Sonia and Lucienne. To throw him off the scent, Hubert admits to having a lover whose husband is an imbecile. Archie guesses that such a designation can only mean his friend, Gorgerot. He threatens Hubert that should he continue to pursue Sonia, he will reveal the matter to his wife, a friend of Mrs Gorgerot. As Hubert leaves, Archie declares his love to Sonia. She reminds him of her mission regarding Hubert, but Archie reveals that his friend has another lover. Undecided on what to do, Sonia affirms that she may be willing in the future. "Blood of Christ!" Archie exclaims, "you love me." He rapturously kisses neck and lips as Lucienne walks in satisfied at what she sees. Unaware of her indifference, Archie explains in a panic that he sought to remove a ladybug dropped on Sonia’s breast, an explanation Lucienne cheerfully accepts. As he leaves, Lucienne kisses her cousin in gratitude. When Sonia mentions that she might return her husband’s love, Lucienne laughs. « Bring him over to Spain, » she advises. When Hubert returns, Lucienne happily discloses that she found her cousin kissing Archie. Hubert is displeased at this piece of news, but Sonia even more so at being bandied about and so decides to leave for the Fine Capon Hotel at Bordeaux. Aghast at this turn of events, Lucienne surprises Archie by announcing Sonia’s intended departure. When he asks for the reason, she mentions that her cousin appeared overwhelmed by feelings of love towards an unknown man and wished to escape from them to the Fine Capon Hotel at Bordeaux. Considering himself the recipient of such love, Archie is at a loss on what to do next. Lucienne pretends to guess that he is troubled about a letter of rejection of his novel from his Paris editor, and so suggests that he head for Paris at once. Archie pretends to agree but heads instead for Bordeaux. Next morning, after faling to find Sonia, he heads for Hubert’s house, accusing him of sleeping with his wife. Hubert denies it. Seeing a woman’s clothes lying about, Archie insists that his friend confess, especially after hearing a friend he met at Bordeaux, Saint-Hilaire, assure him that the rumor was true, all the more likely when Saint-Hilaire told him that Mrs Gorgerot was his lover, not Hubert’s. Moreover, Archie discovers an onyx bracelet in the room, a gift on his part to his wife. Unexpectedly, Lucienne walks in. She, too, is perturbed at seeing a woman’s clothes lying about, more so after seeing the bracelet, the one she gave Sonia as a gift the previous evening. Sonia enters unperturbed. After displaying some irritation at this piece of business, the Burels leave together. Archie comes back to speak to Sonia, followed shortly after by Lucienne to speak to Hubert. Unable to speak in front of each other, the Burels leave together again. After discussing about the possibility of living together, Lucienne returns again to speak to Sonia, who reveals that Archie encouraged her to seduce Hubert. Lucienne leaves to speak to Hubert. Certain that Lucienne will succeed in winning him back, Sonia leaves.

Marcel Pagnol

[edit | edit source]

In addition to comedy, a mixture of Boulevard comedy and drama is a viable art when provided by Marcel Pagnol's (1895-1974) "Marius" (1929).

“Marius is a romance in four acts centered on the opposing attractions for Marius of a life at sea and his love for Fanny...César is not a necessary part of the plot [but] holds the play together...Supervising and dispensing justice with his highly colored exclamations, his gags…and his thunderous interventions dominate the play...Objectionable but lovable, César reaches astonishingly lifelike proportions, as do his clients and accomplices: Panisse, the rotund sailmaker...Monsieur Brun, the dapper customs inspector from Lyons, and Escartefigue, cuckhold and skipper...The unusually high number of private jokes among the characters creates a strong sense of inner complicity in the play...sometimes linked to the traditional gag...Pagnol skillfully varies the dosage of provincialisms according to milieu and mood. Of an inferior social background, Honorine, the chauffeur normally uses more provincialisms, but when Honorine loses her temper, she relapses almost entirely into Provençal dialect...similarly Panisse erupts in Provençal when he catches César cheating at cards...The finer feelings, sentiment and romance, are represented by the younger generation, Marius and Fanny, although the quandary of Marius and his eventual departure also symbolizes a masculine revolt against domesticity. The rock-like permanence and familiarity of these old-fashioned values contribute as much to the play’s continuing popularity as the ebullience and zest of its characters. The play itself is demonstrably one of the finest contemporary comedies of character” (Caldicott, 1977 pp 71-75).

"Marius"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1920s. Place: Marseilles, France.

Text at ?

A port-bar owner, Cesar, tells his son, Marius, that he considers him "soft and lazy", "a dreamer", of litle use at work. While Marius tends the bar in his father's absence, Panisse, prosperous owner of sailing equipment, courts his childhood-friend, Fanny, a sea-side vendor. Panisse gazes so intently inside her cleavage that the two men quarrel. Panisse prefers to walk away rather than fight but proposes a deal to Fanny's mother, Honorine. Should she agree to his marrying Fanny, he will yield a rich dowry for her daughter and a pension for her. Honorine reveals to Cesar the possibility of her daughter marrying Panisse. In turn, Cesar questions Marius about his feelings towards Fanny, who answers he is unsure of loving her sufficiently for marriage and of the existence of another woman he is not inclined to let go, but the real sticking point is his secret desire to head to sea. Fanny refuses Panisse and seeks to delve into Marius' feelings for her. "I love you, and, if I could marry, it would be with you," he answers. But yet he feels the sea calling him. "I long for elsewhere," he admits. One day, Honorine comes charging into the bar, angry and weeping, with Marius' belt in her hand. She found him sleeping with her daughter and tells Cesar she wants them married at once. Meanwhile, Marius strikes a deal with the quartermaster of a ship leaving port, but still hesitates about whether he should leave. Fanny reassures him. "I am not a trap, Marius," she says. "Since you prefer the sea, marry her." She will nevertheless wait for him during his three-year voyage. At the bar, she calls Cesar over and distracts his attention while his son slips out without being noticed towards the port.

Edouard Bourdet

[edit | edit source]

Edouard Bourdet (1887-1945) contributed a Boulevard satire of the seedy side of high society, "La fleur des pois" (Cream of the crop, 1932) and a Boulevard drama, "Vient de paraître" (Hot off the press, 1927) on the seedy side of fiction writing.

In Hot off The Press, “Bourdet presents various types of people in the literary world, all slightly caricatured, but his satire touches only lightly the commercialism that threatens literary production” (Knowles, 1967 p 268).

"Cream of the crop"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1932. Place: Paris, France.

Text at ?

As a main lynchpin for entry into high society, Princess Zaza Volitzine, widow of a Russian prince, though not of the blood, helped Metekian organize his evening. In return, he offers her an expensive necklace, which, without informing him, she returns to the jeweler to cash in the amount. She next receives the visit of Mrs Villemain and her widowed niece, Madeleine, the latter keen on being launched into high society. The princess shows little enthusiasm for this project until Madeline reveals the extent of her wealth, after which she recommends regular church attendance and a change of name to Papou along with brushing up on her piano playing, golf game, and English comprehension. The princess next receives the visit of Albert Tavernier, part owner of an automobile company, interested in publicizing his new car model to her friends so that the mass public will follow. She proposes a series of evening parties at a rich person’s house or expensive restaurant at one of three levels of expense, organized by her but secretly paid by him. He chooses the mid-level one, implying a dinner for 20 people followed by a reception for 40 people with buffet and a jazz orchestra to dance to, worth up to 12,000 francs plus 3,000 francs for the use of Lady Molly Whitford’s home. Her final morning visitors concern Lolotte and his homosexual partner, the duke of Anche, commonly known among intimates as Toto, who is organizing a nautical costume party with himself as Neptune and Zaza as Amphitrite, an idea that depresses Lolotte. Likewise, at Lady Whitford’s house, Metekian is dispirited by the hopelessness of his love for a musician, Serge Grigorieff, whom he saw kissing a woman inside a taxi and becomes even more dispirited when Molly, unaware of his sexual orientation, offers to show him her new Matisse paintings in the bedroom. Because Charlie was seen entering Hedwige’s house late at night with her husband away, they are snubbed by the entire lot of invitees. Serge admits to Zaza that he loves a woman and even more surprising the two are married, so that Zaza proposes the arrange the matter by pretending that the kissed woman was his sister, to La Moufette’s relief as he leaves to reassure Metekian. Molly’s strategy leads to nothing, so that she covers up her frustration by at least dancing with him. Albert, bored at his own party, meets Papou, looking for someone to talk with. She has heard the rumor that the new Tavernier-Lecomte car is mediocre, which he denies. He invites her to the next Volitzine dinner and they even accept to meet again before that event until he blurts out his name and that he paid for the party, at which she walks off snubbing him. An affronted Albert is spied on by Toto, which precipitates a scene of jealousy on the part of Lolotte. Seeing his drunken state, Zaza advises Albert to sleep it off, but he refuses. On Toto’s insistence, she presents him to Albert, who tells him about the Papou episode. Toto sympathizes and expresses an interest in visiting his factory. Seeing the two together, Lolotte is enraged all the more and is restrained by his friends until falling into a beaten down state. Informed about Toto’s interest in Albert and as the man who paid for the party, many express an interest in knowing him, including Papou, who reminds him of his offer to dance. Instead, Albert stalks off to dance with Molly. At the factory, Lecomte is displeased about Albert’s slow progress, who defends himself until Toto is announced, but he is too tired to receive him and so retires to sleep. Instead, Lecomte receives him, whose interest in the visitor increases when he expresses the desire to be driven by Albert to his castle and perhaps buy their new car. Lecomte rushes off to wake Albert while the count expresses to Zaza his disappointment in the car manufacturer, a man who dared to decline the offer of becoming the sixth triton in Neptune’s train. While Toto leaves to consult his costume designer though promising to return, Zaza encourages Albert to accept the triton invitation, but he refuses again, along with the invitation to the duke’s castle, as he suspects the man to be a homosexual. Nevertheless, a decided Zaza drives off to fetch his clothes while Papou enters to be forgiven, but she wants more: the duke’s invitation to join the nautical party. Albert agrees to help her provided she, in turn, agrees for a Sunday drive towards a hotel. Offended, she refuses, but then accepts at least to kiss him after he hits on the idea of asking her to join the duke and him at the castle. At first enraged, the duke accepts on discovering her to be a charming woman. Since a third room is unprepared, the duke sends Albert off to an inn while seducing Papou, now promised a nereid’s part in the nautical party. At the duke’s Paris residence, Charlie is reintegrated in the gang, because a false rumor has circulated of his separation from Hedwige. Informed about Toto’s night of love with Papou, Lolotte returns to warn his old friend that high society may yet avenge itself on him. The duke dismisses the idea and instead requests Papou a second time to inform Albert of their night together. He then declares to the company at large a change in Neptune’s program, the tritons and nereids to enter mixed together instead of apart, the latter astride of the former, and Papou acting as the new Amphitrite. Informed about the Toto-Papou affair by Zaza and then by Papou herself, Albert threatens to win Toto for himself unless the duke buys a car of his. Papou doubts that he can. Alone with Albert, Toto proposes to rearrange Neptune’s program as before should Albert accept him as a lover, but he declines the offer.

"Hot off the press"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1920s. Place: Paris, France.

Text at ?