History of Western Theatre: 17th Century to Now/Early French 18th

Pierre de Marivaux

[edit | edit source]

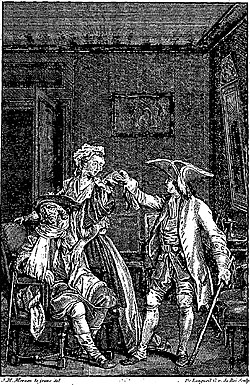

The dominant figure in early 18th century French theatre is Pierre de Marivaux (1688-1763), whose main comedies include "La seconde surprise de l'amour" (Love's second surprise, 1727), "Le Jeu de l'amour et du hasard" (The game of love and chance, 1730), and "Les fausses confidences" (False confessions, 1737). "Love's second surprise" is a revised version of "Love's surprise" (1722) on a similar theme.

In "Love's second surprise", compared with “Love’s first surprise” (1722), “one senses a more polished mastery of thought and style...The marquise and the knight are drawn together by an understanding of each other’s sorrow. [They] wander blindly through the unchartered pathways to the exquisite realization of love” (McKee, 1968 pp 101-102). "When the marquise reads aloud the knight’s letter to Angelique, the two discover an exquisite community of feeling and soon agree to console each other; a pure friendship will be their resource in their common affliction. Each holds a romantic image of the eternally faithful lover, withdrawn from the social whirl; consequently neither realizes the strong physical element in the mutual attraction. The basic data of the play is then the conflict between the physical desires of the pair and the conscious image they have of themselves. For either to propose transforming friendship into love will be difficult, since it will involve destruction of the image and possibly loss of face...[In contrast,] unencumbered by images of themselves which need to be protected and maintained, [the servants] arrive rapidly at mutual comprehension, revealing in advance what will happen to their masters” (Greene, 1965 pp 113-115). “It is interesting to note that [in the reading scene], each measures the other by means of comparison with the previous beloved: the marquise implied that the knight resembles her dead husband because he writes like him; the knight compares the marquise with Angelique...both compare favorably...(Brady, 1970 pp 192-193) “It is through the servants that the marquise [is made to feel jilted. She] will ask the knight, at the first opportunity, for a straightforward explanation. The result of this explanation...is that the protagonists make a step further towards avowal” (Brady, 1970 pp 233-234). “While the intrusion of the count gives an impetus to...a dramatic excitement which was not in the first ‘Surprise’, it does not alter the basic tone. The principal lovers are still hesitant, diffident and interdependent, and when at the end the knights’ feelings can no longer be concealed, the marquise still does not bring herself to utter the word ‘love’...yet her response...is clear enough” (Brereton, 1977 pp 200-201).

“By its formal perfection, the richness and the definitive quality of the text, the complexity and truth of the characters, the variety of the action- alternating emotional tension with exuberance and comic verve, blending the real and the ideal- in almost every way 'The game of love and chance' has proved itself to be a masterpiece of comedy...[Critics recognize] Silvia’s central importance but [misunderstand] what she wants to accomplish...The criticism is that...with Dorante’s revelation of his identity, she should have told him who she was...Critics...see Silvia exactly as do Orgon and Mario...What these critics should add is that Silvia’s long speech in Act 3 Scene 8 is pure histrionics...What Silvia accomplishes in Act 3, through the prolonging of her disguise, is to force Dorante to become fully aware of her as a person of her own right, and to decide that as such she is worth more to him than would be a conventional Orgon’s daughter. Moreover, as Lisette, she is able to say things to Dorante which the proprieties would have made impossible for Orgon’s daughter” (Greene, 1965 pp 126-131). “The necessity for education, the excellence of a simple and virtuous life, uncomplicated by etiquette, the equality produced by a true affection- these are the real subjects of thought in Marivaux's period, but they seldom come to the surface in his plays. If they do, Marivaux is so good an artist as to bring them into direct connection with the intrigue, as when in Le Jeu de l’Amour et du Hasard, the double disguise causes the hero and heroine to think that the one has fallen in love with the soubrette, and the other with the valet. In his first plays Marivaux exercises the diplomacy of love with a sort of ‘précieux’ grace, very reminding of the lighter dialogues of the Elizabethan stage, but in the later plays, beginning with Le Jeu de l’Amour et du Hasard, there is indication of a conflict between the will and passion” (Jourdain, 1921 pp 26-27). “The new idea is Dorante’s willingness to cut across social lines and marry a servant. The spectators know that when the time comes, he will not be reduced to this extremity; but in his own mind he is willing to do so, and the mere proposal of such a radical innovation was bold for 1730” (McKee, 1968 pp 131-132). Dorante “is the only one who has passed the test successfully, whose heart fought against his social upbringing and won; he is the only one who was prepared to face society, family and their opposition. Silvia’s conflict was real only until the moment he revealed his identity, and she had only gone as far as admitting to him that she could love him under certain conditions: fortune, rank, and so on” (Brady, 1970 p 168). "Marivaux's theatre shows us not only a polarity between love and self-love, as countless critics have made clear, but also between love and friendly feelings. The verb ‘aimer’ hides many an ambiguity, which the cognate substantives force into the open. A relationship based on friendship is not wounding to one’s pride, since it does not call for a battle, a conquest, a defeat. In the two 'Surprises de l'amour', the lovers are able for a time to pretend to this fictitious relationship, but eventually the demands made by love become too insistent and force them to the limit of sincerity; and it is precisely at this point that the discrepancy between words and feelings becomes properly comic...In ‘Love’s second surprise’, it is this mask of friendship which must be removed" (Mason, 1967 p 242). The double courtship does “much to complicate the tangled web of sentiment. Its disentanglement between Arlequin and Lisette provides an outstanding scene of human comedy [worthy] of Molière...With Act 2...Silvia still has her game to play- a more dangerous game than in her self-confidence, she thinks- in which she stakes relative happiness for...total happiness...None of Marivaux’ heroines is more spirited, more subtle, more clandestinely vulnerable than this one, his finest stage creation” (Brereton, 1977 pp 202-205). “The most obvious thing about Marivaux, the label which is attached to him historically, is the fact that his style has added the word ‘marivaudage’ to French critical jargon” (Aldington, 1922 p 254). Marivaux' style has been dubbed "marivaudage" when a character talks without meaning anything, a deliberate ploy on the part of the author to exhibit how often we deceive ourselves. "What appeared to be trivialities were pursued ad infinitum and the ultimate meaning of these ‘verbal acrobatics’, maintained the critics, remained elusive and ill-defined...The Marivaudian hero is in constant dialogue with himself and with others, unwilling to recognize his real self on the level of being, and playing a role on the level of seeming...He avoids admitting a ‘truth’ which would destroy this role...As one deceives others, one undergoes self-deception as well. Silvia and Dorante, each disguised as servants, engage in "marivaudage" to avoid the inevitable admission that they love each other. Although each knows the truth, their pride prevents them from admitting or accepting that truth. A battle of nerves results to see who can hold out the longest. During her ‘badinage’ with Dorante, Silvia states that a prediction has informed her that she will only marry a gentleman and Dorante, being a valet, is therefore excluded. Dorante responds: ‘You do very well, Lisette; this type of pride becomes you marvelously, and though it ends my trial, I am still happy to see it; I hoped for it as soon as I saw you; you had also to add that grace and I console myself to have lost it because by such means you win’. A concrete prediction is transformed into an abstract concept; the pride is further extended to constitute an asset to Silvia's other graces; the image is continued on the economic level of gains and losses. This mental ‘game’ not only serves as a delaying tactic, for neither really wants to admit loving the other, but by dealing with every aspect of love except love itself, it becomes a contest in wit and rhetorical expertise...[part of] Marivaux's attempts to create a faithful representation of the thought-process involved in a character's becoming" (Sturzer, 1975 pp 212-218).

"False confessions" introduced a subject new to comedy, the romance of a poor young man making good (Bernbaum, 1915 p 190). "One must stress the cynicism that abounds in the heart of Dubois, who is even more competent at deception than Flaminia, for he himself does not become caught in the web that he is spinning. The assault which he directs upon Araminte [in ‘The double inconstancy’] is carried out with a generous amount of scorn for all around him, master Dorante included. To Dorante's hesitations and fears he returns a clear-cut answer...he is certain [Dorante] will win...The end of each act highlights Dubois rather than Dorante or Araminte...He is willing to deceive, not only Araminte in what might broadly be termed her own interest, but also Marton in nobody's interest but his own. This deception he justifies to himself when he finds that her motives too are interested, but this is invented [after the fact] and reeks of bad faith...What are we to make of the confident assertions uttered by Dubois in Les Fausses Confidences and Flaminia in La Double Inconstance as to the outcome of the intrigues they are directing? Not only do these not destroy the lovers' dignity...they are also less a denigration of any particular human beings than an assertion of the laws of nature to which all human beings are susceptible...In Marivaux's plays the pathos is never very far distant if one reflects upon the characters, their world, and its implications. But this is to extrapolate and thereby to deform in the manner indicated at the beginning of this paper. In general, Marivaux reduces sensibility to the minimum, and where he must allow it a place in order to give the play its proper balance, as in the final scene between Araminte and Marton in Les Fausses Confidences (II,x), or in the scenes from L'Epreuve, where Angelique suffers the mortification of finding that Frontin and not Lucidor is her suitor, he quickly re-establishes a comic atmosphere" (Mason, 1967 pp 240-246). “This is the first play in the French theater that ends by a marriage that cuts across social lines, [though] Araminte and Dorante spring from the same class...Araminte is undoubtedly one of the most ingratiating characters created by Marivaux...She is a dignified yet an utterly delightful person, kindly disposed toward everyone, with no trace of rancor or spite, even toward those who despitefully use her...Dorante has all the grace, all the appealing passion of other Marivaux heroes. As an impecunious young man whose love leads him to seek marriage into a wealthy family he creates much sympathy; and the sincerity of his affection only underscores his admirable traits. But he presents something of an enigma in that he allows his judgment and the course of his romance to be controlled by Dubois...[who] is a transition figure between Scapin and Figaro, [but nearer the latter], for his tricks have less of the buffoonery of Scapin and more of the calculating reason of Figaro...[Few have commented on] Marton, who was as much wronged as Araminte, although the stakes were not so high in her case. She is perhaps only an injured bystander, but to herself her wounds are as sore as those of her mistress; her heart is twisted and her pride is hurt, [and she is] left disenchanted” (McKee, 1968 pp 209-212). “Dubois...has identified himself with his young master...While chasing about Paris, plotting...he fell in love with [Araminte] himself- vicariously. His age, his class, put him out of the running, but he can marry her in the person of his master...From the start...Araminte is subconsciously on the side of Dorante-Dubois, but she has to contend with all the ideas and individuals existing in her conscious mental world, [especially] her mother...a social climber...Although [Araminte] instinctively makes her choice the moment she lays eyes on Dorante, it is a long road from that point to the moment of fully conscious realization that her manager is the man she wants. The moment is one of the finest scenes in French comedy...Remy furnishes a whole set of complications and conflicts, most of them unwittingly. A gruff, hard-headed lawyer, he believes that a successful life must be firmly based on tangible assets...[When Remy realizes that his nephew has been shooting after bigger game], he defends him vigorously against Argante, another of the comic highlights of the play” (Greene, 1965 pp 211-215). The play “is a kind of apotheosis of the servants’ abilities and talents. Dubois is the man who holds the strings in the game:...his recounting to Araminte of Dorante’s love, his participation in the public dispute with Arlequin, his contribution to the interception of Dorante’s letter” (Brady, 1970 pp 238-240). “On a number of occasions throughout the play, we are reminded of the fact that socially Dorante and Araminte are well-matched and that she would not be making a misalliance, if it were not for the money...The whole plot is based on [money]...Almost everyone talks about money...Marton, in spite of her attachment to her mistress...is prepared for the sum of 1,000 ecues to contribute to a marriage in which Araminte’s happiness could be at stake...Even the sweet Araminte...like a good business woman hires a manager to look carefully into the question of [her mother’s lawsuit]” (Brady, 1970 pp 171-173). “Without Dorante’s subterfuge, the possibilities of their coming together are practically non-existent, because they are separated by a real difference in economic status...He hesitates before undertaking this enterprise...But this hesitation is not motivated by moral scruples: it is fear of failure and ridicule...Dorante may well be...a fortune-hunter, but he also is the man who suffers genuinely” (Brady, 1970 pp 330-338).

“What was new in Marivaux' comedy for his own time was that he renounced both intrigue and the notion of conflict in the play, and substituted a series of actions and reactions in the emotion of the characters of his drama. Marivaux's theatre is then really the theatre of the salon, of the sheltered, cultivated, emotional life, with its subtle shades of expression” (Jourdain, 1921 p 25). “Marivaux portrays the most delicate vagaries of the heart and mind in a delicate, allusive, bantering style” (Baur-Heinhold, 1967 p 94).

"The great feature of Marivaux as a dramatist is that he is at once more natural, and more artificial, than the writers who endeavoured to copy the classical model. He consistently employed prose, in preference to verse; nor did he depend for his effects upon such crude contrasts as that between the noblesse and the bourgeoisie. His characters move on much the same plane of life which he himself had successfully invaded; and thus his lords and ladies are treated like human beings, and not like monsters of extravagance and insolence whom chance or necessity has driven into an unaccustomed world. His plays are not written to expose some particular failing, and the absence of a predominating characteristic leaves room for that mixture of foibles which is the rule rather than the exception in ordinary life. On the other hand, the atmosphere of his plays is one generated by a fundamentally sophisticated society. His personages disdain the simplicity and frankness which have always characterised the apolaustic type of aristocracy. Self-examination is everybody's pastime and the critical moments of the action are indicated by exclamations like Silvia's 'Ah, I see clearly in my heart.' Love is the theme on which Marivaux plays all his variations; but we miss the ring of genuine passion, of straightforward affection, which we are sometimes able to catch in Destouches. His heroines, their attendants, and even the subsidiary womankind, are never tired of exhibiting the waves of emotion and the cross-currents of feeling which sweep through their bosoms...They possess individuality, and, though all are more or less coquettes, they are not cast in the same mould. Meticulous psychology is, perhaps, more adapted to the closet than to the stage, and Marivaux has made his influence felt more powerfully in fiction than behind the footlights. Yet it may justly be said that no subsequent dramatist has probed deeper in a certain type of female character, and that not the most psychological, or metaphysical, of latter-day playwrights has placed upon the stage a heroine comparable for vivacity and charm to Araminte or Silvia" (Millar, 1902 pp 237-238).

"Love's second surprise"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1720s. Place: France.

Text at ?

Six months after her husband’s death, a marquise feels she has lost everything. Gazing at the marquise’s countenance, her servant, Lisette, asks ironically: "You make me tremble: are all men dead?". To pass the time, the marquise has hired Hortensius to buy and read books for her, although bearing an "ignorant doctrine", according to Lisette. A knight, having lost the woman he loves, Angélique, who fled to a convent to prevent her father’s choice of an unwanted husband, requests the marquise to convey a final letter to her. In his distracted state, the knight did not seal it, but says she may read it. The marquise approves of the letter and encourages him to remain near her and thereby promote a sympathy in sorrow between them. "If I stayed, I would break off with everyone and would like to see only you," he gallantly comments. "Yes, I would sympathize with you and you with me, which renders pain more tolerable," she agrees. Hortensius is proposed as a reader for both. The knight and the marquise believe that they have renounced love. "Your friendship will be everything for me if you are sensitive to mine," he declares. The knight encounters a count whom Lisette has in view as her mistress’ husband, perhaps with the knight's help, who responds that if he is involved in such a matter, he may spoil all. In the knight’s view, the count does not seem to need him. The count and Lisette are surprised at this cold manner of reasoning. As a result, the count coldly leaves the knight, whereby Lisette reflects that the latter might be willing to love her, too, which he ambiguously denies. In regard to choice of reading, the pedantic antiquity-loving Hortensius proposes "a treatise on patience, chapter one: widowhood”, whereby the marquise impatiently retorts: "Nothing makes me lose my patience more than works that speak of it," preferring something on "the praise of friendship". She scolds Lisette for encouraging marriage prospects with two men of whom she knows nothing. Lisette responds that the apparent refusal of the knight might be insincere. Otherwise, why did he refuse to help the count? The marquise informs the knight that she does not love the count. He laughs at this piece of news, surprised at being the receiver of such intimate sentiments. She then hears that the knight answered Lisette's offer of her hand with disdain, whereby he indignantly answers: "Here is what one may call a fable, an impossibility." He specifies that it is her unwillingness to love that attracted him to her, although she would have been able to console him for the loss of Angélique, were she willing. "I have no proof of that," she responds, "because that repugnance of which I do not complain, should it have been expressed so openly?" Once more, the knight denies he felt any repugnance. "If I did not love Angélique...the only thing you need fear is for my friendship to turn into love," he avers. "That would be too much," she responds. "It must not be, knight, it must not be." His unwillingness to pursue her in that way is due to his assumption that she loves the count, an answer that pleases her. As a result, she dismisses Hortensius and intends never to see the count again. After learning this, the count asks the knight whether he loves the marquise. He answers that their relations are friendly and is surprised to find so persistent a suitor as the count when it is obvious that she feels so indifferent to him. Because the count still considers the knight as his rival, he proposes his sister as the knight's wife. Alone with the marquise, the knight says he accepts this offer of marriage and that he may now speak on the count's behalf. But the marquise is unhappy on both counts. When she encounters the knight’s servant, he hands over an unsent version of a love-letter on the part of his master to the marquise. When the marquise next meets the knight, he is surprised to hear his own letter read, a letter that states his intention to leave in view that he now bears as much love for her as he previously did for Angélique. "What do you wish should become of me?" he asks. "I'm blushing, knight; that's your answer," she responds.

"The game of love and chance"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1730s. Place: France.

Text at ?

To sound Dorante's personality for a possible marriage, Sylvia substitutes herself with her servant, Lisette. But Sylvia's father, Orgon, finds out that Dorante has the same idea. Disguised as servants and unconscious of each other's true identities, Sylvia and Dorante are immediately smitten with each other, the former much less so with his servant, her supposed suitor, Harlequin. A worried Lisette soon informs Orgon of Harlequin's attentions towards her person and is pleasantly surprised to learn that he does not in the least object. Sylvia interrupts Harlequin's verbal love-making towards Lisette to say she is displeased she has not already dismissed "that animal". Lisette answers her father has forbid that. Dorante draws Sylvia apart to reveal his love, who answers she neither loves nor hates him. The lover on his knees begs her to believe it, discovered in this posture by Orgon and his son, Mario. Orgon recommends Dorante to speak better of his master than he has done so far, then asks his daughter whether her bad opinion of the master is due to the attractiveness of the servant. She denies it. To be certain of this, he recommends her to persist in her disguise. Mario predicts she will marry Dorante. After both men leave, unable to tolerate the situation and unable to deceive her longer, Dorante reveals his true identity to Sylvia, which she is glad to hear, though without revealing her own. Later, Harlequin begs his master not to impede the course of his love. A frustrated Dorante retorts: "You deserve one hundred strokes of a stick." His sister having informed him of Dorante's secret, Mario pretends to be her lover and Dorante's rival, at which the latter leaves in pain, to the amusement of Mario and his father. To promote her own happiness, Lisette asks Sylvia whether she consents to yield Harlequin to her, and, to her joy, her mistress does, but first she must reveal her condition. So must Harlequin, who does so hesitantly and gradually: "Madam, is your love's constitution robust? Will it support the fatigue I will give it? Does a bad lodging frighten it?" he asks Lisette tentatively. Finally, he admits his low social condition, which angers her at first and then makes her laugh. When Harlequin reports he has won Sylvia, Dorante cannot believe his ears. He rushes to see Sylvia and is reassured she loves neither Harlequin nor Mario. instead, she leaves him to guess her feelings. "Judge of my feelings towards you, judge of the case I made of your heart by the delicateness with which I tried to acquire it." The amazed Dorante at last discovers Sylvia is the mistress, not the servant. "What enchants me most," he concludes, "are the proofs I gave of my tender feelings towards you."

"False confessions"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1730s. Place: France.

Text at ?

Remy wants his nephew, Dorante, to marry Marton, more of a friend than servant to Araminte, a rich widow. On Remy's recommendation as her lawyer, Araminte hires Dorante as a steward. One day, a dispute flares up about land rights between her and Count Dorimont. To prevent a trial in court and to raise her daughter's rank, Argante would like Araminte to marry the count. Argante orders Dorante to tell her daughter that, independently of her rights, she is sure to lose the trial, but is irritated on finding Dorante hesitate to obey her. Soon after, Marton tells him the count promised her a thousand ecues the day the marriage contract is signed between him and Araminte. Dorante informs Araminte of her mother's plan and his resistance to it, which pleases her. In cahoots with Dorante, Dubois, Araminte's servant and previously Dorante's, imparts to her mistress a secret: Dorante is insanely in love with her. At first Araminte considers dismissing Dorante, then changes her mind and asks him to examine her papers. His opinion is that she is likely to win the trial. Remy thanks Araminte for hiring his nephew, but something new has turned up. One of his rich clients has noticed Dorante and wishes to marry him. Remy is stunned on learning he refuses to see this client, his heart being secretly devoted to Araminte. Remy is even more exasperated when Marton, assured that Dorante sighs for her own person, is even very thankful at the news. While she is conversing with the count, a portrait of a woman is delivered to Dorante. The count, Araminte, and Argante want to know more about this portrait. Marton assures them it is a portrait of her, but it is a portrait of Araminte. Dorante's new servant, Harlequin, quarrels with Dubois about Araminte's portrait he wanted to take out from Dorante's room. For various reasons, the count, Argante, and Marton are all unhappy with Dorante's behavior, but Amarinte has no reason to dismiss him. Amarinte tests him by announcing she will marry Dorimont, whereby his face grows pale and he cannot find the very paper in front of his eyes. He writes trembling on her behalf that she accepts the count's offer of marriage. Because of Dorimante's refusal of a richer marriage, Marton asks him to explain his intentions to their mistress. Dorante tells Araminte he does not think of Marton, but loves another, whose portrait he has painted. She wishes to see it. He prefers not to show it to her. She thinks she has already seen it. Dubois rejoices to hear her say she has noticed nothing particular about his master's behavior. He has a plan: revealing to Marton that Harlequin is carrying a letter from Dorante, which she is meant to intercept. Meanwhile, Argante tells her daughter she wants Dorante out, which makes her laugh aloud. Marton shows them the intercepted letter, revealing that Dorante expects to be fired because of his love of his mistress. Dubois pretends to work against his master by crying out "All the world has been a witness to his folly." He adds: "You would have laughed too hard to see him sigh; nevertheless, I pitied him-" Aramante is so angry on learning that Dubois advised Marton to intercept the letter that she wishes never to see him again. Very sadly, Marton feels the obligation of asking her mistress to dismiss her. Araminte might accept her resignation or not, as she wishes, but Marton admits she entirely misjudged the case, that Dorante loves Araminte "more than any ever did". As Dorante prepares to leave, he requests his portrait back. In Araminte's view, that would be an acknowledgment of love. "And yet," she admits, "that is what is happening to me." He then reveals the entire truth about Dubois' role in the proceedings, which she accepts. To her mother's outrage, she then turns to the count to say she declines to marry him. He sadly promises to accept an out-of-court settlement to their contention. As the masters leave, Dubois brags to Harlequin that in this story he has come off well. "My glory weighs heavily on me," he declares.

Philippe Néricault Destouches

[edit | edit source]

Second only to Marivaux' comedies in the early 18th century are those of Philippe Néricault Destouches (1680-1754), yet nearer Molière's style than Mariavaux', notably when using verse rather than prose. Moreover, themes and manner of presentation resemble Molière's "The misanthrope" (1666), "The miser" (1668), and "The bourgeois gentleman" (1670) in presenting a main character whose major flaw ends in defeating him, copied in Destouches' first four plays: "The curious impertinent" (1710), "The ingrate" (1712), "The irresolute" (1713), and "The scandal-monger" (1715). "The curious impertinent" concerns a man's suspicions of his intended who requests his friend to tempt her to bed, a subject handled with superior acumen by Shakespeare in "Cymbeline" (1610) in regard to a man's relation with his wife. Destouches' dialogue flowed at maximal peaks in "Le glorieux" (The glorious one, 1732), in which the rich middle class begins to get the upper hand over the shiftless aristocracy. The upper class is all the more the target of satire in later works such as “The false Agnes” (1759) containing a baron, a count, and a judge with their wives. The baron is a dupe led to believe he governs his wife when the case is the reverse. The count is a drunk who tries to seduce the judge’s wife in front of her husband’s face and considers his rank a sufficient defense. The title of the play refers to the Agnes of Molière’s “The school for wives” (1662), made stupid by her tutor’s restrictive upbringing. In Destouches’ play, the shrewd Agnes pretends to be stupid to disengage herself from marrying her parent’s choice, a pretentious lout fancying himself as a poet. Destouches is “a playwright always ready and able to please and not seldom rising to the dignity of creative force” (Van Laun, 1883 vol 3 p 9).

In "The glorious one", “the plot is partly based upon a romantic situation of a father who has lost his fortune and who has two children who have not seen him for years. His son is proud and pompous. The daughter does not know who were her parents and has been brought up in a convent as a child not of gentle birth. At the opening of the play, she is half servant, half companion to the daughter of a newly rich bourgeois, who shows her too marked attentions, which she virtuously rejects. She is loved by the son of the household; and in spite of her supposedly humble condition, he offers her honorable marriage in scenes which are distinctly of the sentimental type. Her brother, unknown to her, is in love with, or at least willing to marry the daughter of the rich bourgeois. The humor of the play is furnished by the overweening pride of the young Tufière, by the bourgeois, and also by the inevitable servant. The humor outweighs the sentiment” (Stuart, 1960 p 426).

"The comte de Tufière, whose leading characteristic gives the piece its name, is conceived in the true spirit of Molière, and so is Pasquin his valet...The great merit of Destouches is his excellent common-sense. His ambition was to approximate to what he considered the true pattern of comedy; and this ambition he realised with a success far from despicable. To say that he is habitually decent in tone is to single him out for no special distinction. It is a remarkable, but none the less certain, fact that the whole of the French comedy of our period- or at least all of it which is worth considering as literature- is scrupulously void of offence, without being in the least puritanical or prudish. The conjugal no less than the parental relation enjoys an enviable immunity from serious attack" (Millar, 1902 pp 233-234). Destouches "produced what to a French audience must have seemed like a caricature in the character of the comte de Tufière, but, on the other hand, he was attempting to see the French nobility from the point of view of the middle and lower classes, an attempt which Moliere had only made in certain plays, for example, in Don Juan and in Georges Dandin, and there the satire is disguised because Molière satirises other groups as well. The criticism of the arrogance of the comte de Tufière is put into the mouth of Pasquin, who speaks for the whole class of valets, and points out that the man who is arrogant to his social inferiors is also difficult and conceited with his social equals. Pride, in fact, is the root of all evil, as the mediaeval theologians felt, and is the chief obstacle both to courtesy and to the recognition of the natural equality of man. In Le Glorieux, Destouches carries his thesis so far as to make it appear that the 'suivante', Lisette, though of simple condition, is a good enough match for the hero, but Destouches is conventional enough as a dramatist and thinker to make her turn out to be well-born" (Jourdain, 1921 pp 53-54).

“The vindication of marriage based on heart-felt love becomes a background feature in ‘The glorious one’, Destouches’ most outstanding play...It hinges on the punishment and eventual reform of an arrogantly vain young man, the count of Tufière. His conceit and presumption are represented as aristocratic in contrast to the simpler manners of other characters...Lycandre is more than an affectionate paterfamilias. He is a wealthy nobleman who lost his estates and was forced into exile in England by his late wife’s ‘presumption’ which involved him in a duel and political disgrace...In class terms, the play shows the aristocracy criticizing itself for the arrogance of some of its members. The father image, perfect in Lycandre, is somewhat tarnished in Lisimon, who is attracted to young Lisette and offers in an early scene to set her up in a house of her own as his mistress (he has a wife who does not appear on the stage)...He is nevertheless treated with respect as the father of the second girl, Isabelle” (Brereton, 1977 pp 218-220).

Destouches “has a certain fertility of invention in the way of plots and an unfailing instict for the pathetic in any given situation. He is didactic above all things” (Peirce, 1914 p 105).

"The glorious one"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1730s. Place: Paris, France.

Text at ?

Lisimon proposes to his servant, Lisette, that she be made available to him for sexual favors, but she refuses at once, preferring to remain loyal to his wife. As he reaches out his hand in frustration, she cries out and is heard by his son, Valère, to whom Lisimon's behavior is all too familiar. An angry Lisimon goes away. Valère has his own views on Lisette, has promised marriage, but her dependent condition makes her doubt whether that the match possible, especially considering that his parents are unlikely to approve. A friendly old man whom she knew long ago, Lycandre, interrupts her meditations, surprised to find her in a dependent condition. Although she trusts him to take her away safely, he refuses, assuring her that she is of high descent and that her father himself will soon take her away. Despite her promise to keep the knowledge of her high birth secret, she nevertheless divulges this information to Valère, now both hopeful of the eventual result. Another point of uncertainty is the marriage prospect of her mistress, Isabel, daughter to Lisimon, pursued by two suitors but preferring the count of Tufière over his rival, the timid Philinte, the count bring always confident of his superior condition despite being poor. Despite the latter's attempts to please Isabel, the two can only talk about trivial matters. The count has the advantage of being Lisimon's choice in the matter, but Lisimon's wife prefers Philinte. Although the count finds Lisimon excessively familiar, he nevertheless deigns to follow him for a hearty drinking bout. Isabel herself prefers the count but is flustered over his exaggerated opinion of himself, considering that they should to know each other better before marrying. When Jupière discovers Philinte's existence, he asks Valère to warn his rival that should this rival win, a duel will ensue. Seeing the count lose ground in her mistress' eyes because of his excessive hauteur, Lisette proposes to help out. "Chase away one's nature and it comes gallopping back, but at least constrain yourself," she advises him. After hearing of the count's challenge, Philinte refuses to back off, each facing the other with hand on sword, but they are interrupted by Lisimon, who insists that the latter remove his suit. Although Philinte refuses, Lisimon's wife eventually yields and Lisimon joyfully prepares his daughter's wedding. Meanwhile, Lycandre reveals to Lisette that her father several years ago was led through pride to take part in a duel and killed his opponent. When false witnesses maligned his behavior before the king, he had to escape to England. Since then, powerful friends have rehabilitated him. He further reveals he is himself her father and also father to the count. When he presents himself before his son, the latter begs him to defer showing himself to the others until after the wedding. Although first presented as his steward, Lycandre reveals himself to everyone, preferring to chasten his son's excessive pride. After the count acknowledges him as his father, Lycandre proposes a double marriage, calling forth not Lisette but Constance to marry Valère, a match approved by Lisimon.

Alain-René Lesage

[edit | edit source]

A third satiric author of interest is Alain-René Lesage (1668-1747), deservedly known for "Turcaret" (1709), concerning fraudulent activities occurring in high and low society. The Turcaret character resembles the Jourdain character in Molière's "The bourgeois gentleman" (1670) in his desire to lift himself above his social station, except that Jourdain harms mostly himself while Turcaret harms both himself and others.

“Lesage produced in 'Turcaret' a notable example of dramaturgic skill in that generation. The play deals with the machinations of an unscrupulous and amorous farmer general, duped by a frivolous baroness, who, in turn, is the plaything of a chevalier who extracts from her the money she cajoles from Turcaret. In the end, two servants triumph in this cynical game of love and high finance. The denouement is not only dramatically effective and bitterly logical, but also realistic in view of the prevailing social conditions” (Stuart, 1960 pp 424-425). In "Turcaret","we come to one of the masterpieces of the eighteenth century. It is a play directed against the farmers of revenue who were intensely hated at this period for the dishonest ways in which they made fortunes by handling government taxes. It was a period of wild speculation which culminated in the Mississippi scandal of John Law. With hints from Molière’s Countess of Escarbagnas and Bourgeois Gentleman, he portrayed the duping of the dishonest financier by people even more unscrupulous than himself, who play upon his vanity and amorous weakness" (Wright, 1925 pp 478-479). “Each act begins with a sensational moment and end with a statement or situation which leaves the audience in suspense...In this teeth-grinding comedy, all the characters are either insipid or distasteful...Turcaret is ridiculous; he is also odious; above all, he is stupid and the architect of his own downfall...Frontin is...efficiently amoral, rather than gleefully immoral, a no less chilling consideration” (Abraham, 1986 p 1188-1189).

“Lesage’s originality is found in his making his tax-collector the leading character of his play, in his depicting him as more violent than his predecessors had been, and in his adding details about various characters. We learn a good deal about Turcaret. His father was a pastry cook in a Norman village. He had started life as a lackey in a noble family. He has now reached a point when ‘his prose is signed and approved by four farmer-generals’. He belongs to an important assembly, sells minor offices, engages under the names of others in usurious practices, advises a protégé to enter into bankruptcy with fraudulent intent, neglects to pay his wife’s allowance, is pitiless to an employee who has been robbed...His ruin is caused partly by his shady enterprises and partly by his extravagance in regard to women. The baroness and her friends have little difficulty in tricking him while he is lavishing gifts upon her: a handsome diamond, a carriage and horses, a house, furnishings, a check for 10,000 écues, etc...He is convinced of his own discernment and is unaware that, when his affections are involved, he readily falls a victim to persons less skillful in affairs than himself. The violence of his anger is shown in the scene of the broken minor and vases, but he restrains himself when he is insulted by the marquis. The character would have appeared more ominous if more emphasis had been placed on his nefarious business methods and less on his role as a dupe. This impression is partly remedied by the role of Frontin, whose career lies largely in the future. He is merely a clever valet at the beginning of the comedy, but he is accepted by Turcaret as a clerk and shows his progress in deception by persuading his employer to add to his gifts to the baroness, by deceiving him in regard to the forged bill, and by keeping for himself the money of the his ‘billet à porteur’. He represents the tax-collector in his beginnings, as Turcaret represents him just before his downfall...The other persons are well characterized. The baroness is very clever in her flattery of Turcaret, but she is easily deceived by the knight and his agents. Marine is a relatively honest servant, whose common sense is shocked by the baroness’ infatuation over the knight that makes her run the risk of losing her ‘milking cow’. Lisette has no scruples of any kind and may enter the opera if she does not find it more profitable to build up a fortune with Frontin. The knight makes his living at the expense of women, with his passionate airs, his softened tone of voice, his simpering face’...The marquis, one of the most interesting characters in the play, is a dissipated aristocrat, witty and sarcastic, seeking variety in his amusements, flirting with a queer woman he meets at a dance, able to make something of himself, but preferring to do nothing elegantly while awaiting an inheritance“ (Lancaster, 1945 pp 258-260).

Marine “is frank and has difficulty in hiding her feelings...She speaks on equal footing with her mistress, in which respect she shares the relative ease and familiarity which characterize exchanges of this kind throughout the play...The tone which she displays to others, too, shows no place for subtlety or politeness, unless her own interest is likely to be served...She opposes the prodigal tendencies of La Baronne...Marine’s difference from Lisette lies not in that she is objectively more moral, more disinterested, more sympathetically portrayed, but rather in her attitude towards gambling and acting, towards dependence and independence, towards the future and the present...Marine’s desire foresight, security and hierarchy makes her put her personal ambition second to the establishment of these values in the person of La Baronne...Her championing of immobility is paralleled by her own social stagnation...She shows no sign of sharing Lisette’s ambitions, such as are expressed in the latter’s remark: ‘I’m bored with being a soubrette’...Marine is portrayed as lacking in wit, humour and amiability” (Parish, 1987 pp 175-178).

Lesage “uses the method of realism which we have found in Dancourt, but succeeds in creating a type that is a worse satire on the bourgeois than Dancourt's characters had been. Turcaret has risen in the world, but brings up to the surface all the vices of the different strata of society with which he has mixed. And it is made clear that each section of society claims to rise in turn until the very lowest moves up. At the end of the play, Frontin, the valet trompeur, rejoices at Turcaret's defeat, and believes that his own reign has begun” (Jourdain, 1921 p 15).

"Turcaret is a contractor-merchant-moneylender who lives in luxury amid the destitution of war. He is generous only to his mistress, who bleeds him as sedulously as he bleeds the people. 'I marvel at the course of human life,' says the valet Frontin; 'we pluck a coquette; the coquette devours a man of affairs; the man of affairs pillages others; and all this makes the most diverting chain of knaveries imaginable'" (Durant and Durant, 1965 vol 9 p 29). “The pitiless amasser of wealth, Turcaret, is himself the dupe of a coquette, who in her turn is the victim of a more contemptible swindler. Lesage, presenting a fragment of the manners and morals of his day, keeps us in exceedingly ill company, but the comic force of the play lightens the oppression of its repulsive characters. It is the first masterpiece of the eighteenth-century comedy of manners” (Dowden, 1904 p 267). “Turcaret is a big businessman with the wealth and influence which go with that position. His main weakness is his simplicity in human relationships...[With Frontin escaping with the money in company of Lisette], a dubious character,...not the straightforward follower of so many other comedies...so members of the servant class, already distinguished by their sharper intelligence and grasp of material values, are now climbing the social ladder to financial power...[‘Turcaret’ is] a comedy fast-moving after Act 1 and is distinguished by the wit of the dialogue based on irony” (Brereton, 1977 pp 189-191).

Lesage “was a satirical dramatist of no mean power; and, as a matter of fact, the success of his second comedy, 'Turcaret', was too great to allow him to prosecute it farther in the same direction. This play was aimed against the financiers, who, towards the end of the reign of Louis XIV, wished to make money at any price, and whom Lesage had studied when he was clerk to one of them. They certainly afforded ample material for satire, and Lesage ridiculed them to some purpose, and with greater bitterness than he generally uses” (Van Laun, 1883 vol 3 p 11).

"Turcaret"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1700s. Place: Paris, France.

Text at ?

The baroness' fortune, at a low ebb since her husband's death, is helped by Turcaret, her suitor and an usurer, who, with his usual generosity, gives her a money order for the high sum 10,000 ecues. Despite the advice of her servant, Marina, the baroness removes a diamond ring from her finger so that her other suitor, a knight, in dire financial straits, may pawn it for ready cash. To obtain more of Turcaret's money, the baroness asks the knight to borrow his clever servant, Frontin, so that she may place him in the service of Turcaret. She also requests the knight to take out her diamond ring with the money order just received. Turcaret returns to the baroness in an angry mood, breaking a mirror and some porcelain vases, after being told by Marina, whom she fired from her employ for her insolence, about the true state of the knight's presence, not her cousin as he was told, and about her giving the knight her ring. But when the baroness shows him the ring, Turcaret becomes contrite, now certain that Marina lied, and asks her pardon. The baroness pardons him. "You would be less jealous had you less love and the excessive nature of the first makes one forget the violence of the other," she says while pretending sympathy. Turcaret will replace her broken porcelain and agrees to hire Frontin as an office boy. A conversation between Turcaret and the baroness is interrupted by a marquis, who, to the usurer's consternation, describes to her Turcaret's shady business practices. "He likes men's money and women's honor," the marquis comments. The baroness pretends not to believe him. To help her out in ruining Turcaret, Frontin suggests to his new master that he should buy her a horse-drawn carriage, to which he reluctantly agrees. Frontin next suggests a country-house they later hope to have him furnish, together with a large debt he is fraudulently led to believe she owes from her husband's lifetime. The baroness then receives the visit of Turcaret's sister, by whom she learns Turcaret is married, not a widower as he pretended. During a dinner offered by the knight paid for by Turcaret, the marquis arrives with a supposed countess, a woman also receiving the attention of the knight, no other than Mrs Turcaret herself, first abashed at the knight's entrance, then by her husband's sister's, and finally by her husband's. But worse befalls Turcaret after being seized by creditors for the large sums he owes. Frontin is also arrested, who reports losing the baroness' money order as well as the money fraudulently obtained from Turcaret. The knight's despair at the loss of money opens the baroness' eyes, who repulses both him and Turcaret. When everybody but a baroness' female servant leaves, Frontin declares that he lied about being searched and is thereby able to escape with her along with the stolen money.

Jean-François Regnard

[edit | edit source]

Of equal interest are the comedies of Jean-François Regnard (1655-1709), especially "Le légataire universel" (The universal legatee, 1708), which concerns the deplorable events occurring as family members wish for one's death. As in the novels of Honoré de Balzac one century later, Regnard provides a heavy emphasis on money-related matters in this and other plays such as "The gamester" (1696), evident also in one-act plays such as "The serenade" (1694), "The ball" (1700), and "The unexpected return" (1700).

Schlegel (1846) complained that "The universal legatee" is as "enlivening as the grin of a death’s head. What a subject for mirth: a feeble old man in the very arms of death, teased by young profligates for his property, has a false will imposed on him while he is lying insensible, as is believed, on his death-bed! If it be true that those scenes have always given rise to much laughter on the French stage, it only proves the spectators to possess the same unfeeling levity which disgusts us in the author. We have elsewhere shown that, with an apparent indifference, a moral reserve is essential to the comic poet, since the impressions which he would wish to produce are inevitably destroyed whenever disgust or compassion is excited" (pp 320-321).

“Regnard’s handling of the plot is particularly masterful. The basic situation remains confused and the principals are repeatedly thrown off balance by the appearance of some unforeseen event or character” (LePage, 1986a p 1545). “The principal character is not, as the title implies, the heir, but the old man from whom he hopes to inherit. Like Argan [of Molière’s ‘The imaginary invalid’], Géronte takes much medicine...He is miserly, cautious, in fear of being robbed, wary of all his relatives except Eraste, who approves of everything he says and pretends deep emotion over the thought of his uncle’s death. The other leading characters are the servants: Lisette, bright and bold, an attentive nurse, but one who is by no means disinterested, and Crispin, an imaginative scamp, prepared for the part he is to play in making the will by the fact that he had been for three years a lawyer’s clerk. He puts on three disguises, playing the brutal nephew, the intriguing niece, and the dying old man. He carries his impudence to the point of suggesting that his deceased wife had been Eraste’s mistress and that Lisette is Géronte’s illegitimate daughter. He works brilliantly for his master, but he does not forget his own interests in doing so...Act I is made comic by the racy and somewhat indecent talk of the servants and by Géronte’s remarks about his health and his matrimonial intentions. As Act II is largely concerned with the plot, the author brightened it up by ending it with Clistorel’s farcical scene. Act III is especially distinguished by the antics of Crispin when he is disguised as Géronte’s relatives. Still more amusing is Act IV, which contains the famous scene of the fraudulent will. Act V is less effective, though the second scene with the notary is admirable, and the heirs’ comic suspense is well sustained” (Lancaster, 1945 pp 225-226).

“In 18th-century drama (and in this respect 19th-century drama has followed closely on its antecedents), opinions and social conditions are insisted on, even when these are quite external to the plot. Now Regnard is not himself exempt from this habit; he shows, in fact, the first symptom of the change in Le Joueur, and Le Légataire Universel: though he has less of what, from the point of view of drama, we may call a defect, than the writers of the ‘drame bourgeois’. A good deal of time is, however, taken up in his plays by the description of circumstances that do not develop character. We are told at length in Le Légataire Universel about Géronte's will, about his relations and the different plans for the disposal of his money: but Géronte is left by the dramatist in the last scene of the last act exactly where he was at first” (Jourdain, 1921 p 9).

“The presumed death awakens echoes of Jonson’s ‘Volpone' and of Molière’s ‘The imaginary invalid’...but with the difference that in both cases the dead man is playing a trick on his heirs, while in 'The universal legatee' the trick is played on him...The play is predominantly Crispin’s...Some of the language is mock-tragic. On learning of Geronte’s recovery, he utters the unmistakenly Racinian line: ‘And avaricious Acheron again lets go its prey’” (Brereton, 1977 pp 180-181).

"The universal legatee"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1700s. Place: Paris, France.

Text at ?

Eraste hopes to obtain the legacy of his uncle, Geronte, and thereby marry Isabelle according to the wish of her mother, Argante. But Geronte, whom Eraste thought dying, surprises him by wanting to marry Isabelle himself. Eraste pretends to be overjoyed at this bit of news. Though Isabelle recognizes her duty to her mother, she is far from keen on the match. To curry favor with his uncle, Eraste pretends to agree with the idea. As they discuss the matter, Geronte must leave because of a pressing need of nature. "O power of love!" exclaims his servant, Lisette. But to Argante, Eraste renews his wish to marry her daughter. Argante assures him that if his uncle grants him the legacy, he will indeed obtain her hand and sends Geronte a letter stating she has changed her mind about the marriage. Because of illness, Geronte is relieved at this and tells Eraste he will make him his universal legatee. Eraste pretends to be saddened by the thought of his uncle's death and pretends to approve of his generous legacy of 40,000 ecues to another nephew along with a niece, both of whom he has never even seen. To thwart the nephew's legacy, Eraste's servant, Crispin, disguises himself as that nephew, a country gentleman from Normandy. Crispin shows himself grossly eager to obtain the legacy. Shocked by his attitude, Geronte now says he will disinherit him. To thwart the niece's legacy, Crispin disguises himself as the niece, who swears she heard Geronte was "a drunk, a gambler...haunting day and night places where honesty suffers and modesty moans" and that he has had many children by Lisette, all of which she comes to correct. Offended, Geronte orders her out, a gesture Eraste warmly approves. Shaken by this experience, a weak Geronte leaves the room and has a fainting spell in his chamber. Having had no time to change the will, the nephew and the two servants are extremely alarmed about his condition. Crispin proposes to put his hands on all the goods he can. After looking about the house, Eraste is able to salvage 40,000 ecues. To fool the notaries into changing the will, Crispin disguises himself as the dying Geronte and names Eraste as the universal legatee. "O too bitter pain!" Eraste cries out, pretending to be moved. But to Eraste's horror, the insolent servant grants 2,000 ecues to Lisette and 1,500 francs to himself. The notaries are fooled, but, as they leave, Lisette re-enters in great fright, having discovered "Geronte on his legs". Not knowing much what to do, Eraste hands the money over to Argante and Isabelle. Feeling better, Geronte calls his notary over and is puzzled on learning that the will was already changed that very day, but assumes it is the result of his lethargy. He is content with Eraste as his universal legatee, but is stunned on learning about the sums destined for the two servants and about the ready money he lost on his person. Eraste assures him that, according to his commands, he handed the money over to Isabelle. The uncle is distraught and refuses to approve of the will unless the money is found. To the relief of all, Isabelle arrives with the money.

Charles Rivière Dufresny

[edit | edit source]

Charles Rivière Dufresny (1648-1724) is another comic dramatist of note, especially for "Le double veuvage" (The double widowing, 1702).

In "The double widowing", "husband and wife, each disappointed in false tidings of the other's death, exhibit transports of feigned joy on meeting, and assist in the marriage of the irrespective loves, each to accomplish the vexation of the other” (Dowden, 1904 p 262). "The intendant has laid up a considerable fortune, perhaps at the expense of the countess. He is pleased to hear that his wife is dead and is eager to marry Therese, but he must keep up appearances (III, 2). His wife, who is called the Widow throughout the play, is as hypocritical as he and duplicates his actions. When they meet in the dark, the fact that Dorante’s voice resembles his uncle’s deceives the woman, while her imitation of Therese’s voice, attempted in order to discover Dorante’s sentiments, deceives her husband. He still thinks she is Therese when he reproaches her for wishing to marry Dorante, while she supposes the voice she hears to be that of her husband’s ghost. The result is that she faints and he becomes more and more amorous till a lighted candle, brought by an attendant, disillusions them. This is an effective comic scene, the best in the play. Dorante is a young nobleman who shows that he was created m the eighteenth century by his insistence upon “sensibility” in his sweetheart. Therese, however, is as gay and pleasure loving as he is sober and reasonable. The first obstacle to their union is his fear that she does not love him because she does not tremble when they meet. His own reaction is quite different...He is already a Romantic, but one in love with a child of the seventeenth century, with whose attitude the author sympathizes more than he does with her lover’s. The countess, though she appears little, prepares the intrigue and brings it to a happy conclusion. She is moved by her interest in the young people, her dislike of their rivals, and her desire for amusement” (Lancaster, 1945 pp 201-202).

“The double widowing" "deserves remembering as the classic of realism on the married state and sentimental love...Under the mockery of the old-style lover, one can sense the beginnings of the new and lighter love which Marivaux will develop. [At the start], Theresa is not really as heartless as she appears...But it is a very timid beginning and the main emphasis of the play runs against the sensitivity or tenderheartedness which Dorante alone shows...If even the young lovers are allowed few illusions, the cynicism of the older characters is complete...This realistically heartless play pleased contemporaries...There is certainly no moral lesson or intention...a kind of comedy new in tone and manner, not a comedy of character...,[one] that Dufresny broke free from” (Brereton, 1977 pp 184-187).

“The titles of Dufresny's plays always take the form of the paradox which suggests the type of plot treated in them; besides those already mentioned we might instance Le Double Veuvage and Les Mal-Assortis, and Le Malade sans Maladie. They are written in prose and are so witty that they repay reading, even though what Dufresny calls the play’s architecture' is sometimes hurried and imperfect...Like Regnard, Dufresny works on quite conventional lines, trusting to the brilliance of his dialogue to carry off his pieces. He enhances this effect by constantly bringing on to the stage some character who is acutely aware of the motives and absurdities of the others. Frosine acts this part in Le Double Veuvage” (Jourdain, 1921 p 11). “Here is an agreeable variation on [Dufresny’s] favorite theme: “some amuse themselves for the sake of ambition, others for money interests, others for love, common people for pleasures, great men for glory, and I amuse myself by considering that all of this is but amusement’” (Aldington, 1922 p 364).

"The double widowing"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1700s. Place: Paris, France.

Text at http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/5193

Dorante and Thérèse wish to marry but have no money. To provide them with some, a countess devises a plot. Thérèse's aunt is told that her husband, the countess' intendant, has died while on duty to serve his mistress. "When news of her husband's death were given, I perceived that his death only afflicted her face," the countess reports. After four days of pretended grieving, the countess asks the supposed widow for money on behalf of Dorante and Thérèse. The aunt declines, saying that the state of widowhood would make her niece too unhappy. The real reason is that she wants Dorante as a husband for herself. The countess specifies she expects 10,000 ecues from her. Otherwise, she threatens to take money away from her, because she has not signed all the business papers regarding her husband. The intendant arrives one day earlier than expected. Thinking his mistress too frivolous, Dorante is overjoyed at seeing Thérèse's unhappiness at this hindrance to their plot. Seeing Dorante and others in mourning clothes, the intendant is puzzled as to who has died and deduces that it is his wife, a notion that is not contradicted by the countess' majordomo, Gusman. The intendant pretends to be full of sorrow but yet appears stoic. "You withstand all this like a Caesar," Gusman declares. He then tells him she died on learning of his death. The intendant is truly touched by this piece of news, but becomes angry after learning that she perhaps died of joy. In love with Thérèse himself, the intendant is worried on finding out that she is about to marry Dorante this very day. To prevent his interference, Thérèse asks him to protect her, pretending that she does not wish to marry Dorante because he is too poor. The countess requests her intendant to give his nephew money so that he can marry. But he is hopeful that Thérèse will marry him instead, having obtained her promise to do so. Meanwhile, the supposed widow begins to flirt with Dorante, who shows no interest though without offending her. At last she agrees to give Thérèse the money provided her husband is not Dorante. When Gusman sees the intendant approach the supposed widow, he turns off the lights to delay their being able to recognize each other. In the dark, the intendant thinks he hears Thérèse's voice and the widow thinks she hears Dorante's voice. When she names Dorante, the intendant is angry at what appears to be Thérèse's betrayal. He learns that his wife is alive and loves Dorante at the same moment she learns that her husband is alive and loves Thérèse. Both are outraged. Each wish to send away their rivals, but when the countess agrees to send both away, husband and wife are chagrined. To resolve the matter, the countess agrees to provide the money and both agree to the marriage proposal between Dorante and Thérèse.

Jean-Baptiste-Louis Gresset

[edit | edit source]

Jean-Baptiste-Louis Gresset (1709-1777) is especially remembered for "Le méchant" (The villain, 1747), concerning a man's gratuitous plots of scandal-mongering amid a peace-loving family.

“The immediate source of Gresset's Méechant seems to be...Congreve's Double Dealer (1693)...Maskwell, a villain, pretended friend to Mellefont, gallant to Lady Touchwood, and in love with Cynthia. This character is the Méchant who, in turn, is a villain, pretended friend to Valère, gallant to Florise and in love with Chloe. Mellefont, ‘promised to and in love with Cynthia’, is the counterpart of Valère, promised to and in love with Chloe, who corresponds to the English Cynthia. Lady Touchwood is at first in love with Mellefont in the Double Dealer, but she is afterward in love with Maskwell and becomes his coadjutress. This character is Gresset's Florise, who, though not in love with Valère at any time, is yet in love with Cleon and becomes his coadjutress in attempting to keep Chloe and Valère apart. Lord Touchwood and Sir Paul Plyant coalesce into the one character of Geronte. The degree of relationship is somewhat changed between Geronte and Chloe, he being her uncle, while in the Double Dealer, Sir Paul Plyant is Cynthia's father, and Touchwood is Mellefont's uncle. But as Touchwood first favors his nephew and then will hear no good of him, so Geronte first favors his young friend Valère, but becomes strongly prejudiced against him. Another point of similarity between these characters lies in the fact that Sir Paul Plyant, true to his name, is hen-pecked, while Geronte, though not so ridiculous, weakens before Florise (Act 1, sc 1). It cannot be said that Ariste has any prototype in the English comedy. He warns Valère against Cleon and this warning is delivered to Mellefont by Careless; but beyond that, the two have nothing in common. However, neither is of vital importance to the action. Lisette and Frontin are the stock soubrette and valet, inevitable in French comedy; and we need not look for their source in the English version. Of course, in Congreve's play there are other characters, but the main plot could be unfolded without them. Indeed, had the dramatist preserved the unity of action, practically none of them would have appeared” (Stuart, 1912 pp 43-44).

Schlegel (1846) complained that "The villain" "is one of those gloomy comedies which might be rapturously hailed by a Timon as serving to confirm his aversion to human society, but which, on social and cheerful minds, can only give rise to the most painful impression. Why paint a dark and odious disposition which, devoid of all human sympathy, feeds its vanity in a cold contempt and derision of everything, and solely occupies itself in aimless detraction? Why exhibit such a moral deformity, which could hardly be tolerated even in tragedy, for the mere purpose of producing domestic discontent and petty embarrassments? (p 325)

"The foible which Gresset selected for his theme was the mania for fashionable life which sometimes possesses the young, and even the middle-aged and elderly. Valère, the hero, is an amiable young gentleman of property with no serious failings, but so bitten with this craze that he is ready to sacrifice his mistress and her money for the sake of 'fins soupers' and kindred diversions...He has become imbued with these sentiments by Cleon, whose leading characteristic supplies the piece with its title. Cleon himself is thoroughly used; he finds the pleasures of Paris extremely tiresome; but he is full of the cant of the 'philosophes', and has no difficulty in proving to Valere's satisfaction that duty of every description is a mere convention. 'Everyone one is for himself' is his motto and by dint of a little seasonable ridicule he keeps Valère in the way in which he should not go. Ultimately, the duplicity of Cleon is exposed, and Valère returns to reason and to Chloé. The real interest of the play lies in the attack upon the life of Paris. So set is Gresset upon pursuing this topic, that, with perhaps less good judgment than Piron would have shown, he puts his strongest condemnation of the capital into the mouth of Cleon himself" (Millar, 1902 pp 229-230).

It is “a character play with an exciting plot...Cleon is a bad man in every sense. He stirs up trouble partly through self-interest, partly through sheer malice. He courts insincerely the immature Florise, then aims at her sweet young daughter, Chloe. He is attracted by her uncle’s money, but equally and perversely by the charm of her pure simplicity. He misleads his trusting friend, Chloe’s true lover, in an attempt to betray him. He poisons other relationships and is ready to use a legal weapon to ruin the uncle figure, Geronte. He is the sum of wild young men of previous plays, but...dangerous until the end...His badness is presented as inherently temperamental and never analysed...He is bad, but not evil...representing all the anti-bourgeois qualities in an extreme form: sexual promiscuity, contempt of marriage, contempt of the family...and with that, the corruption of smart society in Paris. Uncle Geronte is immensely proud of his house with its landscaped park and garden, he never tires of showing visitors round them. As Cleon remarks to another: ‘you must prepare to follow him everywhere...He will not spare you from a head of lettuce.’ But the country virtues are the true ones...[In the play, the word ‘wit’ has degenerated] to superficial cleverness...The ingenuous young heroine totally lacks wit in any sense of the word, [her overriding concern being] to please her mother” (Brereton, 1977 pp 228-230). One may argue that in addition to sheer malice, the villain is motivated by a wish to decrease his sense of boredom.

"The villain"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1740s. Place: Provinces outside Paris, France.

Text at ?

Geronte wants Chloe, the daughter of his sister, Florise, to marry Valère, Chloe's childhood friend. Thereby, he senses he will have the "authority of a father" towards the young man. Moreover, he wants to avoid being taken to court by his sister, since the question of their parents' inheritance is unclear. In addition, his friend, Cleon, seems to approve of his choice, as does Valère's mother. However, Florise resists, because should Geronte die before her, all his fortune will go to the young couple instead of her. Nevertheless, she is willing to agree should Cleon, a man whose wisdom she trusts and on whom she has an eye to marry, consider favorably her brother's choice. If not, Chloe will be sent to a convent. As Chloe enters, her mother coldly says that her hairdo is horrible and then leaves. A dispirited Chloe wonders what has she ever done to displease her mother. Cleon has no love for Florise, but is nevertheless willing to entertain the possibility of marrying her should they be assured of her brother's money. He would more particularly like to seduce Chloe. In any event, he enjoys causing trouble for no reason. He therefore commands his servant, Frontin, to write two unsigned negative letters on Valère's character to Florise and Geronte and at the same time pretends to be his friend. "Silly people are here below for our little pleasures," he points out to a bewildered Frontin. He assures Florise that, contrary to what Geronte thinks, he disapproves of the planned marriage. He also assures her of his love and encourages her to take Geronte to court. However, she is unwilling to go to this extreme. Considering him to be his friend, Valère joyously greets Cleon. When asked about his mother's plan to marry him off, Valère assures him he has no such intention, preferring a young man's free and easy-going life. However, Chloe's servant, Lisette, desires a marriage for her instead of a life in the convent. Lisette cautions her lover, Frontin, if he still wishes to marry her, to disobey his master's order by not going to Paris. Valère's mother sends over her brother's friend, Ariste, to finalize the marriage plans. Cleon hypocritically agrees with both Geronte and Ariste on that question. However, the marriage plan seems dashed when Valère enters. To Geronte's disgust, the young man appears frivolous. Even worse, the young man entertains the possibility of dismantling his property after his death. After reading the anonymous letter on Valère's character, his mind is made up: no more talk of marriage! A little later, Valère meets Chloe and realizes almost at once his mistake. Lisette suspects Cleon's work in Geronte's rejection of the marriage proposal and assures Valère and Chloe, also suddenly smitten by love, of her willingness to help. Lisette proposes to her mistress that she hide herself while she speaks of her to Cleon. She agrees. To her astonishment, Cleon reveals his true feelings, calling her "ridiculous" and "odious". Lisette next recommends Frontin to write a letter to his master announcing that he is quitting his service, as she intends him to follow Valère. With a specimen of the servant's writing in hand, Ariste discovers that he was the scrivener of the anonymous letter on Cleon's behalf. When told this, Geronte considers it the work of the knavish servant, but when Florise shows him Cleon's letter to his lawyer requesting help in suing him, Geronte shows Cleon the door and agrees to Valère's marriage with his niece.

Voltaire

[edit | edit source]

For 18th century tragedy, there is Voltaire (1694-1778) with "Mahomet le prophète" (Mohammed the prophet, 1741), a worthy study based on historic sources, and "L'orphelin de la Chine" (The Chinese orphan, 1755), best described as a tragicomedy.