History of Western Theatre: 17th Century to Now/English Romantic

Corrigan (1967) pointed out that, unlike those in tragedy, melodramatic characters mainly suffer from external causes. Thus, there is an “overriding tone of paranoia” throughout melodrama. This explains the “overpowering sense of reality that the form of melodrama engenders even when on the surface it seems so patently unreal". Because the suffering is unfair, the style often reflects “grandiloquent self-pity”. Unlike tragedy when the individual is divided and in conflict with himself from within, the melodramatic character is “whole” and the issue becomes the “reordering of one’s relations with others". Donohue (1979) specified that "melodrama depends on a structure of transparent fantasy, presenting a world of wish-fulfilment in which evil, given apparently unlimited scope, ultimately proves to be impotent. The ethical premise of melodrama is that evil must be contained, and that it is containable; its correlative theatrical premise is that the audience must see evil contained, in a climactic way, at the end. Even as the subject matter of melodrama evolved over the course of the century, and settings and characters of rural Bohemia, for example, gave way to those of urban England- that is, even as melodrama became ostensibly more realistic- its conflicts continued to be resolved, and resolvable, in the exterior world, rather than within the characters themselves. Inner turmoil, except in the case of a villain stricken with an adventitious conscience, remains by and large unknown to the characters of melodrama, who are each the true embodiment of a basic theatrical type and who wear their moral orientations on their sleeves...The climactic 'coup de théâtre', though found in other forms as well, is an essential ingredient of melodrama because it is the direct means of reordering the world at large to suit the deserts of the virtuous" (pp 92-93).

"Melodramas follow a basic formula. A virtuous woman undergoes dire sufferings at the hands of a traitor; but strict poetic justice is meted out. The virtuous characters are rewarded and the traitors are either punished or die repenting their sins. A comic character is usually numbered among the virtuous and often plays an important role in the denouement. This character is an old soldier, a servant of some sort, or may be a rather good-natured coward on the side of the traitor" (Stuart, 1960 p 487). Since the early 20th century, critics respond poorly to melodrama. “Life is usually independent of intrigue, suspense, and the other trumperies of dramatic contrivance that strike us as so ridiculous in the dialogue of Victorian melodrama” (Gassner, 1956 p 46). A true statement to many, a dubious one for some who think that the statement can only be true of bad melodrama; good melodrama is often more suspenseful than good dramatic realism.

In addition to melodrama, there is the advent of a more sentimental comedy than Sheridan and Goldsmith envisaged. “Perhaps the most barren period in the history of comedy is the first half of the nineteenth century” (Bentley, 1955 p 129). A critic born in this period, Leigh Hunt, complained of the decline in British comedy. “A comic writer of the present day may be immediately distinguished by his dislike of all those difficulties which oppose a writer ambitious of imitating the best models; the whole object of his pen seems to be the attainment of applause in the easiest manner possible, and he accordingly writes for the galleries, or, in other words, for that part of the audience which is the least capable of judging, but the nosiest in declaring its judgment. He appeals, therefore, to the eye and to the ear, because they are the soonest pleased with the least reason; a new piece of scenery or an uncouth dress conquers the visual faculties of the spectators, and a volley of puns is the signal for the author's triumph. This artifice of punning, which has become a perfect system with the dramatists, is the method by which the author rids himself of the difficulty of wit, as his flowery language, when he becomes what is called sentimental, is his device to forego the necessity of thinking. By these means language becomes separated from ideas, since mere punning is nothing but an unexpected assimilation of sounds, and mere floweriness, like a harlequin jacket, is nothing but a surprising combination of colours. The incidents and characters of his pieces always agree in one alternative: they are either of very manifest commonplace, or they are clad in the most monstrous disguises to gain the appearance of novelty; they remind us of the tricks practised, according to a modern traveller, at some of our country fairs, where a vulgar woman has been dressed in catskins and a tumultuous periwig, and exhibited as a wild Indian, not to mention a shaved bear, who, in a check shirt and trousers, gained a great deal of applause as an Ethiopian savage. If he exhibits a character that has been too often handled to stand inquiry, he gives a new tone to its appearance by some prominent peculiarity of manner, which, however ill-adapted it may be, immediately catches the attention by the mere force of oddity, and deprecates your censure for the sake of the laughter it creates. This peculiarity generally consists in some hackneyed phrase or cant maxim, which is used upon all occasions, seasonable and unseasonable, and is very often as suitable to the mouth of the speaker as a tobacco-pipe would be in the lips of the Venus de Medicis” (1894 edition pp 131-132).

"Is there anything that unites all heroes of sentimental comedy? Perhaps it is their common conviction that virtue is a definite and simple thing, that it is not to be found among the wise and learned, that it need but be discerned to transform life, and that it pays. A curious blending of the spirit of the Gospel with that of the Enlightenment, of ancient sayings concerning the wisdom of the foolish with those verses in which Edward Young declared that 'All vice is dull,/A knave's a fool./And virtue is the child of sense.' It follows that in this art of the theatre, if in no other, we cultivate prettiness and are afraid of beauty” (Lewisohn, 1922, pp 29-30).

Fitzgerald (1870) adumbrated the difference between the theatre and the novel, taking as an example a stage version of Dickens' "David Copperfield" (1850). "Turn to the story, and we find that [David's] is the mind which reflects and colours the whole course of events to us. Through him, as it were, we see every character: it is his mind, his feeling, the mind of the author himself, and his own life that fills up the whole. Through the eyes of David look forth the eyes of the writer; his quick wit, his genius, illuminates that figure, brings out the wit and humour of others, as steel does with flint, and illustrates their doings with a sort of commentary. Thus Copperfield becomes the soul of all. We turn to the stage, and all this must disappear; there remains but a figure in a long coat and gilt buttons, who walks on and walks off, and is about as purposeless as one of Madame Tussaud's images" (pp 55-56).

“The construction of romantic tragedy differs from that of melodrama in two respects. The point of attack is earlier in the newer form of drama. Thus, the narrative exposition of the melodrama is generally replaced by exposition in action in romantic tragedy. This is a distinct gain, for nothing is more inartistic in the theatre than mere narrative before suspense has been aroused. Had the romantic playwrights followed Shakespeare’s practice, they would have chosen a still earlier point of attack. The greatest difference between the two forms appears in the last act. The melodrama ended happily. Romanticists could not be so bourgeois as to believe in the reward for virtue. No means of escape from death was allowed in their scheme of art for hero or heroine. The final impression left by romantic drama is tragic; but it is not well to inquire as to the inexorable logic of the denouement either of melodrama or of romantic drama. A tragic last act is only apparently inevitable when the determining element in the action is chance” (Stuart, 1960 p 511).

Percy Bysshe Shelley

[edit | edit source]

Verse dramas of the like of "The Cenci" (1819) by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822), based on the life of Beatrice Cenci (1577-1599), renewed in part the might of Renaissance tragedies in its episodes of murder, torture, and incest.

"Nowhere else in Shelley...does this world drama come out of the clouds and reveal itself with such clarity and power. There is passion in the persons, climax in the situations, and directness in the language such as the romantic drama had rarely shown. The philosophical conception and the tangle of human motives do not indeed quite harmonize. Beatrice's lie and her unworthy seeking after life are bits of the story which interfere with our acceptance of Beatrice the martyr" (Thorndike, 1908 pp 353-354). The latter comment is disputed by several critics. Gassner (1954a) was impressed with the gallery of Romantic characters. "Beatrice is a magnificent heroine, worthy of Webster, if not of Shakespeare; her equally unhappy stepmother, Lucretia, is a deeply realized portrait of a helpless victim; and several of the other characters are etched with remarkable precision. Although Count Cenci is a melodramatic villain, he is also more than that. He is the product of unchecked power and social corruption which is condoned by the Church, then in its moral nadir. He has always been able to buy off the guardians of justice with a slice of his property, and he can think of no crime that he cannot commit with impunity. His victims, led by the wronged Beatrice, can find no alternative to having him murdered. And such is the state of society and of the Church (which is not, however, without one noble representative) that it is only when the victims have risen up to defend themselves that the long arm of justice intervenes. Suddenly it is discovered that 'law and order' have been violated, and Beatrice and her associates are executed! Beatrice, condemned by her papal judges, goes to her death unbroken in spirit and triumphant in her tragically won knowledge of 'what a world we make, the oppressor and the oppressed’- a vision worthy of Euripides" (pp 344-345).

Fischer-Lichte (2002) commented that "Shelley bases 'The Cenci' on two particularly popular literary genres, the domestic play and the gothic novel. From the domestic play, he adopted the relationship of the father and child, principally father and daughter. From the gothic novel, he took the relationship between the aristocratic villain and the innocent victim. Shelley bound these two ideas to one another and turned them around: the tender father, who protects the virtue of his daughter from her seducer, turns into the fiend who threatens the daughter’s virtue himself; the innocent victim, who protects her virtue under the most hideous of circumstances, commits patricide...The event that triggers his daughter's rape is when she tries to counter his sons' deaths. Cenci believes he can only regain his position by transforming his sole antagonist, his daughter, into an image of himself. To do this, he must enact a ‘deed which shall confound both night and day’ (II,2,183), a deed which will ‘poison and corrupt her soul’ (IV,1). Beatrice experiences the rape in a fundamentally different way to that experienced by the violated innocent girl of the gothic novel (for example, Antonia in 'The monk') who sees the act as a violence done to the body which does not, however, touch upon her ‘angelic’ being in any way. Beatrice, on the contrary, experiences it as a distortion, poisoning and dissolution of her body in which something has occurred ‘which has transformed me’ (III,1). She has been wounded to the innermost self: ‘Oh, what am I?/What name, what place, what memory shall be mine?’ (III,1). “Beatrice exhibits the necessary defiance of evil, but she lacks the fortitude to resist hatred. She confuses physical violation, which any person with sufficient opportunity can inflict on another, with spiritual violation, which requires willful complicity. By hating, she comes partially to resemble the thing she hates” (O’Connor, 1994b p 2184-285). Beatrice senses that the only way to find her self again, to halt the process of self-alienation caused by the violation, is to banish it at once, otherwise she will fall into the danger of a total loss of self, a total ‘metamorphosis’...When Beatrice decides to kill her father in order to recover her self, it becomes apparent to what extent her ‘metamorphosis’ has already begun: her speech contains almost exact echoes of sentences uttered previously by Cenci" (pp 215-217).

“Cenci unleashes the self’s energies when he turns within, but his son, Giacomo, is paralyzed by self-anatomy; he loses the ability to act when he looks within to discover the desire to kill his oppressive father...Only Beatrice herself can confront the self without falling prey to its dangerous lure” (Cox, 1994 pp 161-162). "The uneasy vacillations of Giacomo, and the irresolution, born of feminine weakness and want of fibre, in Lucrezia, serve to throw the firm will of Beatrice into prominent relief; while her innocence, sustained through extraordinary suffering in circumstances of exceptional horror- the innocence of a noble nature thrust by no act of its own but by its wrongs beyond the pale of ordinary womankind- is contrasted with the merely childish guiltlessness of Bernardo. Beatrice rises to her full height in the fifth act, dilates and grows with the approach of danger, and fills the whole scene with her spirit on the point of death. Her sublime confidence in the justice and essential rightness of her action, the glance of self-assured purity with which she annihilates the cut-throat brought to testify against her, her song in prison, and her tender solicitude for the frailer Lucrezia, are used with wonderful dramatic skill for the fulfilment of a feminine ideal at once delicate and powerful" (Symonds, 1879 p 127). “Beatrice’s murder of her father ultimately fails because it is an act in isolation against only one tyrant, but tyranny runs through the whole of her society” (Mulhallen, 2010 p 90). "Beatrice's unhinging has its psychological component in the breaking of an incest taboo, compounded with the horror of rape. It also has a more conceptual component in her assuming false alternatives as to the nature of the act: either that the incest has somehow never taken place, or that it has become for all time part of her essence. In this error we find the key to the Beatrice who orders the murder of the count, and the Beatrice who unheroically denies that she has participated in the murder plot" (Lockridge, 1988 p 97). Only after killing her father does Beatrice believe she has found herself again; this is no longer true after her condemnation. But unlike tragic protagonists recognizing their flaw in the sense given by Aristotle's "Poetics" (335 BC), "at the end...she continues in the delusional belief of her own innocence" (Dempsey, 2012 p 880). "Beatrice gives up hope of escape. In her despair, she turns to her God. It is not her father's God of Power or Shelley's God of Love but it is the only one that, in his eyes, her distorted religion has to offer: a just and vengeful God" (Whitman, 1959 p 252).

"The Cenci"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1590s. Place: Italy.

Text at http://www.bartleby.com/18/4/ https://archive.org/details/cencitragedyinfi00shelrich

Count Francesco Cenci invites several guests at his palace to celebrate the death of two of his sons for stirring enmity against Pope Clement VIII. Stricken with grief, his wife, Lucretia, half-faints amid the celebrations. Although her step-daughter, Beatrice, cannot believe this to be true, letters from Salamanca confirm the rumor. Cenci is angry at his daughter and nurtures a black design against her, at which she staggers. "My brain is hurt;/My eyes are full of blood-" she confesses to Lucretia. "The sunshine on the floor is black. The air/Is changed to vapors such as the dead breathe/In charnel pits." A priest and friend but also would-be lover, Orsino, arrives to speak with Beatrice. "I have to tell you that, since last we met,/I have endured a wrong so great and strange/That neither life nor death can give me rest," she confesses to him. He recommends her to accuse Cenci openly for the murder of her brothers, but she prefers instead to kill him with his help and Lucretia's. Cenci's other son, Giacomo, informs Orsino of his own wrongs: "This old Francesco Cenci, as you know,/Borrowed the dowry of my wife from me,/And then denied the loan; and left me so/In poverty, the which I sought to mend/By holding a poor office in the state./It had been promised to me, and already/I bought new clothing for my ragged babes,/And my wife smiled; and my heart knew repose./When Cenci’s intercession, as I found,/Conferred this office on a wretch, whom thus/He paid for vilest service." The count then addressed himself to Giacomo's wife. "And when I knew the impression he had made,/And felt my wife insult with silent scorn/My ardent truth, and look averse and cold,/I went forth too: but soon returned again;/Yet not so soon but that my wife had taught/My children her harsh thoughts, and they all cried:/"Give us clothes, father, give us better food". He then reveals the outrage his father committed on Beatrice, a crime about to be avenged. At the stroke of midnight, Giacomo waits for news of Cenci's murder, but Orsino reveals instead that Cenci passed the appointed place too soon, so that they missed him. Distraught, Lucretia pleads with her husband one last time. "Pity thy daughter; give her to some friend/In marriage: so that she may tempt thee not/To hatred, or worse thoughts, if worse there be," she pleads. He says little except to command Beatrice's presence forthwith. When she fails to appear, he curses her: "Heaven, rain upon her head/The blistering drops of the Maremma’s dew/Till she be speckled like a toad; parch up/Those love-enkindled lips, warp those fine limbs/To loathed lameness!" Now convinced that only her husband's murder will bring them peace, Lucretia mixes an opiate in his drink. In his sleep, two hired malcontents strangle him as the legate of the pope arrives to speak with him, carrying a death-warrant for his crimes. The legate discovers the corpse caught among branches of a pine-tree after it had been thrown from the castle. Officers of the law then discover the two murderers. One dies while resisting arrest, the other is seized carrying an incriminating letter from Orsino to Beatrice. Orsino confesses his crime under pains of torture to judges in Rome and dies without accusing Beatrice. But Lucretia and Giacomo cannot bear the pains of torture and confess the truth. Beatrice does not. "Turn/The rack henceforth into a spinning wheel," she cries defiantly to the judges. But despite the lack of any confession, she, too, is condemned. "O/My God! Can it be possible I have/To die so suddenly?" she wonders, "So young to go/Under the obscure, cold, rotting, wormy ground,/To be nailed down into a narrow place,/To see no more sweet sunshine, hear no more/Blithe voice of living thing, muse not again/Upon familiar thoughts, sad, yet thus lost?/How fearful! to be nothing!" Yet after many painful ruminations, she becomes reconciled to her fate.

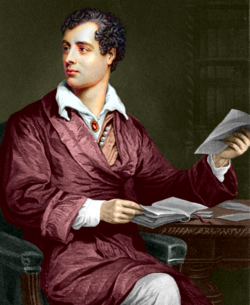

Lord Byron

[edit | edit source]

"Manfred" (1817) constitutes the best effort from Lord Byron (1788-1824) in the domain of verse tragedies. The play contains tight affinities with Goethe's "Faust", whose protagonist is constantly restless, unsatisfied, seemingly searching for the impossible.

"The gloom and remorse of a solitary spirit, gathered into a dark cloud of miserable individual self-absorption, aware with semi-sympathy of the free unfettered glories and splendours of external nature, intellectually, even emotionally alive to them, yet undelivered from its prison, were never more powerfully presented, neither was passionate affection, nor the pathos of frantic grief for a beloved person, lost in death, with the damnation of whose soul the lover upbraids himself. But the dealings in magical arts of this proud Baron, shut alone in his castle, are not described with the power of Goethe in Faust, which partly suggested Manfred. The scenery, however, is very fine, notably the passages about the Alps and the Coliseum at Rome. The poem is virtually a monologue, though a hunter appears, and an old abbot. The passion of the invocation to lost Astarte is immense. This poetry is the expiring groan of self-centered individuality, that has not yet found freedom and happiness in ministering to others" (Noel, 1890 pp 121-122).

"Nature, the ever-recurring theme of the romantic poets, is here given something akin to dramatic treatment. The impassioned descriptions create a presence, not one 'that disturbs him with the joy of elevated thoughts', but 'the wild comrade of Manfred's antipathy to men'. The mountains become sharers in the hero's tirades, though their nights' 'dim and solitary loveliness' is the only power that curbs his fierce unrest" (Thorndike, 1908 p 352.

“Manfred is a solitary, partly by inclination, partly by consciousness of superiority to his fellow-men,…partly by the weight of crimes and grief...He is a man of mystery and crime, and linked with these crimes he has...the questionable virtue of devotion to one only love...The abbot of Saint Maurice embodies the implicit acceptance of dogma as opposed to the search after absolute truth...Byron gives clearest expression to this opposition to traditionalism...But with the sneer at the priestly attitude there is mingled a sense of the pathos of a mind confined by authority” (Chew, 1915 pp 66-82).

"Manfred is substantially alone throughout the whole piece. He holds no communion but with the memory of the being he had loved; and the immortal spirits whom he evokes to reproach with his misery, and their inability to relieve it. These unearthly beings approach nearer to the character of persons of the drama, but still they are but choral accompaniments to the performance; and Manfred is, in reality, the only actor and sufferer on the scene. To delineate his character indeed- to render conceivable his feelings- is plainly the whole scope and design of the poem and the conception and execution are, in this respect, equally admirable. It is a grand and terrific vision of a being invested with superhuman attributes, in order that he may be capable of more than human sufferings, and be sustained under them by more than human force and pride" (Jeffrey, 1970 p 116).

“Manfred is superior to other mortals and alienated from them; he is pursued by the unrelenting furies of a private guilt. Neither an atheist nor a revolutionary, he is yet defiant of powers and structures outside of himself, including the demands of such systems as pantheism, Manicheanism, and Christianity...proffered by the Witch of the Alps, Arimanes, and the abbot...Manfred is ironically dubbed as a short term of 'Man Freed', a projection of the Romantic ego which triumphs in its independence and skepticism, while deepening the ironic dimension of his status as hero. A hero, yes- but he is a cursed hero, doomed for all his independence” (McVeigh, 1982 pp 603-604).

"Alone in death as in life, Manfred has no more communion with hell than he has with heaven. He is his own accuser and his own judge. This is Byron's manly ethical standpoint. Not till he reaches the lonely heights above the snow-line, where human weakness and pliability do not thrive, does his soul breathe freely. And the Alpine landscape is the natural, inevitable background for his hero whose stern wildness is akin to such scenes" (Brandes, 1906 pp 308). Manfred “rejects the abbot’s attempt to impose a doctrinal apparatus on his final moments. ‘Give thy prayers to heaven,’ the abbot exhorts...Manfred refuses to expire on any terms but his own, saying ‘old man! ’tis not so difficult to die’ (III, iv, ll. 144–51). They both insist, like [Don] Juan, on controlling their own final hours and meeting death on their own terms” (Mole, 2018 p 238). "Until the very end, Manfred demands radical autonomy: the joy of self-fulfilment is denied him; neither man nor spirit, heaven nor hell, can give any sense to the guilt and sorrow which follow from the resulting self-alienation. All that is left is for Manfred to be his own ‘damnation’, his own ‘destroyer’, with consequent self-determination. He is not prepared to confer value on any system of order, any authority, other than that of his self. The only quality to which he attaches great importance is his autonomy: this he realises with a rebellious gesture against any who contend his right of self-determination. The aristocratic villain of the gothic novel, who in the end is forced to recognise the existence of higher values, is transformed into a metaphysical rebel for whom all values outside his own self-autonomy are utterly meaningless" (Fischer-Lichte, 2002 p 214).

"Manfred"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1810s. Place: The Alps.

Text at http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Manfred https://archive.org/details/dli.ministry.04144 https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.181008

Seeking forgetfulness if not oblivion, Count Manfred summons spirits of air, mountain, ocean, earth, wind, night, and star, but these are unable to tell him whether death brings forgetfulness. While attempting to seize the seventh spirit, he collapses. After recovering, Manfred climbs atop Jungfrau mountain to plunge into a precipice, but is rescued in time by a chamois hunter. Manfred gives him gold as a reward for his care, but, dismissing his encouraging words, leaves him suddenly. Near a torrent, Manfred calls on the witch of the Alps, to whom he admits he once loved a woman named Astarte. "She had the same lone thoughts and wanderings,/The quest of hidden knowledge" as his, but his love was responsible for her death. The witch declares she may be able to help him. "To do this thy power/Must wake the dead, or lay me low with them," he responds. Nevertheless, she answers she may, provided he become obedient to her will, but he refuses to submit. Instead, he requests Nemesis and the Destinies to raise Astarte from the dead. She appears but cannot be made to speak, either by them or by their ruler, King Arimanes. When Manfred beseeches her to speak to him, her only answer is: "Manfred! Tomorrow ends thine earthly ills." In Manfred's castle, the abbot of St Maurice requests him to be reconciled to the church, to which he responds: "I shall not choose a mortal/To be my mediator." He fears no after-life. "There is no future pang/Can deal that justice on the self-condemn'd/He deals on his own soul," he pronounces and leaves abruptly, but the abbot catches up to him in the castle tower. A spirit intervenes in the abbot's view. "From his eye/Glares forth the immortality of hell," the abbot cries out fearfully. This spirit or demon calls himself "the genius of this mortal" and requests Manfred to follow him. He refuses. More demons appear. Manfred commands them all away. "My past power/Was purchased by no compact with thy crew,/But by superior science, penance, daring,/And length of watching, strength of mind, and skill/In knowledge of our fathers when the earth/Saw men and spirits walking side by side/And gave ye no supremacy: I stand/Upon my strength -" Although he succeeds in freeing himself from them, the effort overwhelms his forces. No longer able to see the abbot or anything else, Manfred asks to touch his hand. In the abbot's opinion, Manfred's hand seems "cold- even to the heart". "'Tis not so difficult to die," Manfred concludes as he fades away in death.

John Keats

[edit | edit source]

John Keats (1795-1821) wrote an underrated verse play: "Otho the Great" (1819), based on the life of Otto I (912-973), German emperor. The play resembles in many ways Shakespeare's history plays, sometimes providing novel poetic images, sometimes only weak echoes.

“Shakespeare’s influence is evident throughout Otho...In places, Otho recalls Hyperion’s epic manner, as in ‘bruised remnants of our stricken camp’ or Otho’s ‘Olympian oaths’ (I.ii.127, I.iii.14) and its celestial imagery included skies ‘portentous as a meteor’ (III.i.65). Elsewhere, Keats’s dramatic poetry grew comparatively austere and restrained” (Roe, 2012 pp 333-334).

Keats' friend, Charles Armitage Brown, wrote in his memoir of Keats: "I engaged to furnish him with the fable, characters, and dramatic conduct of a tragedy, and he was to embody it into poetry. The progress of this work was curious; for, while I sat opposite to him, he caught my description of each scene, entered into the characters to be brought forward, the events, and every thing connected with it. Thus, he went on, scene after scene, never knowing nor inquiring into the scene which was to follow, until four acts were completed. It was then he required to know, at once, all the events which were to occupy the fifth act. I explained them to him; but, after a patient hearing, and some thought, he insisted on it that my incidents were too numerous, and, as he termed them, too melodramatic. He wrote the fifth act in accordance with his own view; and so enchanted wasI with his poetry, that, at the time, and for a long time after, I thought he was in the right" (1987 edition pp 54-55).

One of the sources of “Otho the Great” "was William Fordyce Maver’s Universal History, Ancient and Modern...[including] the Hungarian uprising of 953-954...’Otho the Great’ gives little development of character and only occasional glimpses of Keats’ powerful language. Most of these occur in the last act...By this time, Ludolph, rather than his father, Otho, has become the centre of attention, and the original attentions of the play have altered...Ludolph is denied his final revenge on Auranthe...The climax gives the play its only moment of real dramatic power” (Motion, 1997 pp 219-222).

“Otho the Great portrays the first Holy Roman Emperor and contains a neat parallel to Henry IV, Part I, in the disaffection of father and son, healed by the son's saving the father's life in battle” (Eggers, 1971 p 997). “Several episodes are similar to those of Shakespeare. The character of Ludolph, the protagonist, is individual in the highest degree. He is a hot, proud, obstinate boy who has been spoiled by an indulgent but autocratic father. His tragic trait is an excessive emotional instability which makes him oscillate between the extremes of feeling. He lacks the balance of character, that harmony between emotion and reason...He betrays his fatal emotional instability in every scene of the play in which he appears. In the scene after his marriage, he indulges in such an excess of joy that his father, his wife, and his friends find it a little painful. When Abbot Ethelbert accuses Auranthe of having foisted her guilt of immorality upon Eminia, he swings through a gamut of emotions from murderous rage to scornful in difference; and when Auranthe shows her guilt by flight, he gives away to an excess of jealous fury. In the final scene, his emotions are stimulated until his reason topples” (Finney, 1963 pp 662-664).

"The power of sympathetic insight had not yet developed in Keats into one of dramatic creation; and the joint work of the friends is confused in order and sequence, and far from masterly in conception. Keats, indeed, makes the characters speak in lines flashing with all the hues of poetry. But in themselves they have the effect only of puppets inexpertly agitated: Otho, a puppet type of royal dignity and fatherly affection, Ludolph, of febrile passion and vacillation, Erminia, of maidenly purity, Conrad and Auranthe, of ambitious lust and treachery. At least until the end of the fourth act these strictures hold good...The fifth act...shows a great improvement. Here is a real dramatic effect, of the violent kind affected by the old English drama, in the disclosure of the body of Auranthe, dead indeed, at the moment when Ludolph in his madness vainly imagines himself to have slain her; and some of the speeches in which his frenzy breaks forth remind us strikingly of Marlowe, not only by their pomp of poetry and allusion, but by the tumult of the soul and senses expressed in them" (Colvin, 1887 pp 176-177). “There is no doubt that Keats had more of the real dramatic attitude than his chief contemporaries. His sympathy flowed more genially than theirs into stand-points diverse from the poet's own: the freedom from ‘self-passion or identity’ which he noted in himsefl is often quite Shakespearean. His Endymion is more dramatic and his Tragedy of Otho the Great more promising than critics steeped in lyric atmosphere have perceived” (Elliott, 1921 pp 319-320).

"Otho the Great"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 10th century. Place: Germany.

Text at http://www.bibliomania.com/0/6/244/1882/frameset.html http://books.google.ca/books?id=ZbMIdsJQdyQC

Conrad, duke of Franconia, has earned Emperor Otho's respect by beating down a rebellious Hungarian army. As a reward, Otho consents that Ludolph, his son and heir, marry Conrad's sister, Auranthe. As a sign of general good will, he also sets free Gersa, prince of Hungary. A prisoner in the Hungarian camp, Erminia, niece to Otho, discovers among Gersa's spoils a compromising letter Auranthe wrote to Conrad, seeming to indicate brother-sister incest. This letter is shown to Albert, a loyal knight in Otho's army, who promises to reveal it to the emperor but fails to do so, because he wishes to protect Auranthe. Erminia, accompanied by Etherlbert, an abbot, arrive too late to prevent the wedding between Ludolph and Auranthe. They nevertheless accuse Conrad and Auranthe of incest, but neither Otho nor Ludolph believe the two. Albert shows the letter to no one, and so Erminia and Etherlbert are sent to prison for falsely accusing the royal pair. At last, Albert threatens to expose Auranthe, but, to secure her escape from the emperor's wrath, he proposes to wait for her with horses. Instead, she and her brother plot his death. While Auranthe pretends to lie sick on her wedding-night, Gersa steps up to Ludolph with the truth, which he angrily dismisses. "Look; look at this bright sword;/There is no part of it, to the very hilt,/But shall indulge itself about thine heart!" Ludolph threatens. Mutual threats are interrupted by a page announcing that Auranthe and Conrad have fled together. Gersa then discovers that Albert cannot be found either. Ludolph promises revenge. He discovers Albert in a forest, already wounded by Conrad, and threatens death unless he reveals where Auranthe is. "My good prince, with me/The sword has done its worst; not without worst/Done to another,- Conrad has it home!" Albert answers. Auranthe arrives aghast. Ludolph mockingly invites her to complain of her lover's death, then takes her away, leaving the dying Albert where he is. Meanwhile, Gersa succeeds in freeing Ethelbert and Erminia from prison. In the banqueting-hall, Ludolph's mind appears unhinged. "When I close/These lids, I see far fiercer brilliances,-/Skies full of splendid moons and shooting stars,/And spouting exhalations, diamond fires,/And panting fountains quivering with deep glows./Yes- this is dark- is it not dark?" he cries distractedly, then calls for music but is dissatisfied with this as well. Before the entire court, he threatens to kill the disloyal Auranthe, but she is revealed to be already dead.

William Wordsworth

[edit | edit source]

Like "Otho the Great", "The borderers" (1842) first written in 1795-96 by William Wordsworth (1770-1850), is a history play, only more removed from Shakespeare's influence despite Oswald's resemblance to Iago and Marmaduke's to Hamlet (Smith, 1953), nearer instead that of traditional English and Scottish ballads.

“The Borderers is set in thirteenth-century England and Edward, the Longshanks of Brave Heart, is a bit player...Mortimer and Rivers's tense debates and the denouement, which ensnares new characters in guilt and yet is circumstantial if not accidental, are replicated in dozens of plays, as are the grieving speeches that put Matilda in the spotlight. The most difficult thing for a playwright who has never been an actor or even stagehand is to master theatricality and producible interpretation, and Wordsworth's limitations do show. For example, the scene between Rivers and Mortimer in Act 3 in which Rivers believes Mortimer has duplicated his own crime and will, therefore, live his life in the same state of mind is, indeed, ‘obscure’, as Harris and Sheridan described it, primarily because it is too intellectual and undramatic” (Backscheider, 1999 pp 316-317).

“The events of the play clearly show that the associations of benevolence can be sidetracked by deliberately perverted reason...A society with evils to correct encourages the Marmadules, who wish goodness to reign, into a misidentification of the evils to be corrected. The deceiving class of the reckless empirics flourish when social order has been disrupted...The Borderers examines the effects of social disruption rather than its cause” (Woodring, 1965 pp 16-18). “The borderers” “has considerable dramatic merit...Oswald, after learning of the captain’s innocence, is at first overcome with remorse. He is also in disgrace with his fellows...But he is too energetic to withdraw from the world and accordingly is bound to re-establish his self-respect by reasoning himself into a new morality, constructing a set of values at odds with those of society. Having done so, he is ‘free from the world’s opinions and usages’ and feels like ‘a being who has passed alone into a region of futurity’...[After Marmaduke] has been deceived, his speeches become pessimistic or bitterly cynical...He will become a voluntary outcast, alone and shelterless” (Nesbit, 1970 pp 115-121).

“Both Oswald and Marmaduke are men to whom a grave wrong has been done...Oswald and Marmaduke alike, through deception by others, have been made responsible for an innocent man’s death...An unfair cruel blow has been struck at one utterly underserving of it, who trusted and believed his environment...But...the response of each is different. In Oswald it leads to deliberate evil, in Marmaduke to resignation and the life of religion ‘in search of nothing that this earth can give’...Though in part [Oswald’s] treatment of Marmaduke was animated by resentment of a universe of experience which had betrayed him, a resentment which he vented on the conspicuous virtue of Marmaduke, it was also inspired by a certain inverted idealism, a pure assertion of the will, which sought to issue an enlargement of ‘man’s intellectual empire’. This pure, disinterested assertion of the will, concerned to maintain itself in disregard of good, became in the heart of Oswald a demand for a pure freedom, free from the claims of shame, ignorance and love” (James, 1970 pp 38-39).

“When Marmaduke discovers that he has been duped, the result is moral chaos, and, like so many other sinners in romantic literature, he becomes an unhappy wanderer in the waste places of the world. What Wordsworth has done is to exhibit the spiritual ruin consequent upon unhampered individualism. Godwin had claimed the infallible power of the reason to recognize the truth, but Marmaduke's tragic blundering discloses what Wordsworth, with unflinching intellectual honesty, had come to think of such dogmatic confidence” (Sprague Allen, 1923 p 268).

“Oswald...consumes numerous lines in inciting Marmaduke to murder, and later defends his conduct by picturing murder as intellectual emancipation” (White, 1922 p 212). “Oswald represents an Iago-like satanic seducer who makes his own laws. He is not only the instrument of the unraveling of the plot, but also a man fatal for others and himself. Man is his own fate: Oswald tries to prove it and fails unrepenting” (Hoffmeister, 1994 pp 174-175). “Oswald’s plot to trick Marmaduke into murdering Herbert was particularly odious because the victim was not only innocent but old, blind and helpless” (Welsford, 1966 p 147).

“The root of Oswald’s depravity is his vindictiveness and innate pride; his moral destruction of Marmaduke is unprovoked except by the fact that Marmaduke once saved his life and Oswald dislikes being under the obligation of any man... Oswald’s great aim was to make Marmaduke repudiate conscientious scruple, pity, and remorse, and act as circumstances and reason only direct” (Moorman, 1957 pp 303-307). Oswald’s “revenge is not against his deceivers but against an innocent young man who reminds him of himself before he had acted against his original innocent victim...Oswald wants to disguise envious destructiveness as a special privilege of merit, the aristocratic version of the animus against the world” (Heilman, 1978b pp 77-79). Oswald expresses “a high regard for reason and a relative disregard for feelings as guides to moral conduct...Oswald's meditations in his retirement made of him an introspective egoist, convinced above all else of the powers of the individual self-sufficient mind, when it is freed of its usual dependence upon external things"...Moreover, he sees himself as existing...'in a universe that it is valueless, in human terms- it is morally neutral, indifferent to all human good and evil'. [But unlike Byron’s 'Manfred', Wordsworth shows] the terrible dangers of this self-sufficiency of the individual mind... Marmaduke is from the first the soul of benevolence, if with no very strong mind. He has firm faith in two principles: first, in the untutored intuitions of the heart into the goodness of others; second, in the ultimately moral nature of the universe...Although Marmaduke's faith in his second principle is not restored, to an extent his faith in his first principle is. Herbert had indeed been innocent, he discovers, and had he obeyed the intuitions of his heart against Oswald's 'proofs' (and it is well to remember that not only Marmaduke, but all the rest of the band are for a time convinced by these proofs), the tragedy would have been averted. This realization plunges Marmaduke into the deepest remorse, and, unlike Oswald, he refuses to abandon his guilt, for in it he finds the only identity left him, the last remnant and realization of his humanity” (Thorslev, 1966 pp 86-102).

Allen (1923) criticized Herbert and Idonea as “a lachrymose picture of virtue in distress; the blind old man is a sentimentalized Oedipus, and his daughter is a Greuze maiden, a girl with a broken pitcher, who has stepped out of her frame to go a-wandering; her angelic perfection only exasperates. Even the 'little dog, tied by a woollen cord', that guides the wandering Herbert, has a sentimental pedigree; he is the faithful animal of current novels- the descendant, for example, of virtuous, old Trusty, the 'shag house-dog' of ‘The man of feeling’...Marmaduke is a noble nature against his better impulses led into crime by Oswald, a Machiavellian villain, who undermines all his principles by Godwinian arguments. He scoffs at Marmaduke's compunctions, urging him to be superior to pity, to reject those general principles by which weak, unthinking creatures guide their conduct, and to decide what is right by the aid of his own unfettered reason. When Marmaduke discovers that he has been duped, the result is moral chaos, and, like so many other sinners in romantic literature, he becomes an unhappy wanderer in the waste places of the world” (pp 267-268).

"The borderers"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 13th century during King Henry III's reign (1216-1272). Place: Bordererline between Northern England and Scotland.

Text at https://archive.org/details/dli.granth.41223 https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.97288 http://www.everypoet.com/archive/poetry/William_Wordsworth/william_wordsworth_120.htm

Amid furious battles between British borderers and Scottish bandits pilfering England, Baron Herbert disapproves of Idonea's love for Marmeduke. "My child, forgetful of the name of Herbert,/Had given her love to a freebooter/Who here, upon the borders of the Tweed,/Doth prey alike on two distracted countries,/Traitor to both," he declares. But yet Marmaduke is told by a beggar-woman that Idonea is not Herbert's daughter, since she herself gave him the child raised as his own. In actual fact, this woman was paid to lie by Marmaduke's disgruntled colleague, Oswald, to entrap his leader, whom he calls one of those "fools of feeling". Oswald hates Marmaduke because he once saved his life, thereby losing face before his comrades in arms. As a result of Oswald's insinuations, Marmaduke suspects Herbert intends to deliver Idonea to Clifford, a dissolute baron. Marmaduke also hears of a silent madwoman suspected of being Herbert's bastard. For all these reasons, Oswald tempts Marmaduke to take Herbert's life while sleeping in Clifford's castle. Late at night, Marmaduke hovers over the sleeping father, but is unable to do it. Nevertheless, this case is discussed with the entire band of borderers, who decide that Herbert should be put on trial, their own selves acting as justicers. Marmaduke has a second opportunity to kill Herbert, this time on the moor, but once again he is unable to. Meanwhile, the borderers discover Oswald's treachery by means of the beggar-woman's confession. Unconsciously, on leaving Herbert in the wilds, Marmaduke takes away his script of food. On coming back to look for him, he discovers his unintended victim too late, lying dead from hunger. When meeting Idonea, Marmaduke admits his fatal negligence, at which she faints. Found guilty of treachery towards their leader, the borderers kill Oswald. Yet Marmaduke will no longer fight the Scots with them or even marry Idonea, but instead wanders away: "Over waste and wild/In search of nothing-" he announces gloomily.

Dion Boucicault

[edit | edit source]

Dion Boucicault (1820-1890) succeeded in comedy with "London assurance" (1841) and also in melodrama, especially "The octoroon" (1859), the first notable British play set in the United States.

“Boucicault" wrote his first important piece, London Assurance, with his eyes on Sheridan and the elder Colman” (Tolles, 1940 p 20). “It is essentially written in the style of a Restoration comedy, and is suggestive of the work of such authors as Sheridan, Congreve and Goldsmith” (McFeely, 2012 p 6). “The setting could easily have been the middle of the 18th century as the 19th” (Fawkes, 1979 p 35). “The term ‘London Assurance’ appears to suggest various quite unsavoury qualities in Charles Courtly that will be challenged in the move to the country. His father, Harcourt, also manifests some of the worst aspects of London assurance in his physical vanity that is captured by his use of a wig and rouge, but also in his determination to pretend to be much more youthful than he is” (Griffiths, 2022 p 101). “The author has displayed a vivacity, a fearless humour to strike out a path for himself, an enjoyment of fun, a rapidity in loading his speeches with jokes, a power of keeping up his spirits to the last, which distinguishes this piece from every work of the day” (London Times March 5, 1841, in: CE Pascoe (ed) The Dramatic List, 1879). "Youthful high spirits offset its artificial wit, and boisterous good nature tempers the elegance of Dazzle...when he exerts his London assurance upon country gentlefolk for their own good. Sheridan’s traditions stamp the morals as well as the style. Drunkenness, divorce and debt, serious evils to the minor drama, are subjects for humour here" (Disher, 1949 p 227). “Artificial and full of fustian as the play is, there is in it for the stage an unmistakable heartiness and vigor of movement and dialogue and a lively vein of humor that persist even in the pages of the text. Something of the life of the town-bred, titled gentleman and his household is presented in the first act as we enter the rather carelessly conducted establishment of Sir Harcourt Courtly, a practical, unsentimental Victorian version of the middle-aged gentleman of means and social position. His son, Charles, is the young blade who drinks and does not pay his bills, but is within easy hail of reform when he hears the call of love. Young blades like Charles Courtly go on their happy, unchecked way, drinking and reveling; the town is their hunting-field, life their toy, women their especial game. Burgundy is drunk before breakfast, Sir Harcourt Courtly oils and perfumes his locks, gentlemen sing rousing songs while alone after dinner. They still duel, may be arrested for debt, and travel by post-chaise; they wear jabots, turned-over cuffs, military cloaks, white beaver hats, satin waistcoats and curly wigs. The language they affect is rhapsodical, surcharged with sentiment. The later acts of the play, taking place upon the estate of a country squire, present an amusing series of involvements and mistaken identities with the expected denouement” (Sawyer, 1931 pp 44-45). “Grace Harkaway is a witty heroine in the tradition of Congreve’s Millimant, while Lady Gay Spanker, ‘glee with a living thing’, carries the last three acts with her enthusiasm” (Oxley, 1994 p 310). “Grace is able to tame her lover because she has a better understanding of the ways of the world and sees beneath his disguises and also, pragmatically, because unknown to him she hears the crucial exchange between Gay and Charles at the end of Act Four in which Charles says ‘I will bend the haughty Grace’, to which her response, unheard by Charles, is the curtain line of the fourth act: ‘Will you?’...The staging here frames her as the true manipulator of plots, who will succeed in taming Charles in Act Five. Unlike many Romantic Comedy endings, her success involves more than reconciling apparently competing plot strands because not only does she get her man, she also pays his debts, a reminder that she is master of his fortunes as well as his emotions as well as a telling reminder that, while the course of true love may not always run smooth, a sensible heroine guards her future and her fortune” (Griffiths, 2022 p 103). “Eventually the London assurance of the town men is overturned by the country wit of Grace and Lady Gay; everything gets sorted out; the young couple will marry and inherit the estate; Sir Harcourt sheepishly admits defeat, and speaks, in the end, against London assurance and for a more truly ‘gentlemanly ease’ of manners. It's a conventional play (in the best sense of that word), and something of a disparate collection of elements, at that…but it's exuberant, rapid, and unabashed” (Williams, 1998 p 50). "The Olympic, in 1831, began the school of what we call modern comedy. Its distinguishing features, unlike those of the conventional type that preceded it, were: the observation and reflexion of contemporary life; the interpretation of that life in terms of itself; the representation of it by fitting costumes and scenes; and the enactment of it by a naturalistic, if not natural, imitation. In London Assurance they came nearest to bringing the written drama into accord with their principles" (Watson, 1926 p 211). “The comedy’s strength lies in its characterizations. Although the dramatist relied upon familiar types from the comedy of manners (the young rake, the aging lecher, the unfaithful wife, the fop, etc), he endowed the people of London Assurance with individuality and good humor. Best of the characters is Lady Gay Spanker, Boucicault’s original creation. Lady Gay is a bold and bouncy horsewoman who greatly enlivens the proceedings as she flirts with the old roué and scoffs at her milksop husband” (Vaughan, 1981 p 115). When "London assurance" was revived at a later date, Scott (1899) complained of the realist style of acting being imposed on it. "When ‘London Assurance’ was revived at the Prince of Wales’ Theatre under the Bancroft management, the part of Lady Gay Spanker was played in the modern style. The famous description of the hunt was spoken by Mrs Kendal, seated at a drawing-room table, precisely as a lady in real life would relate the incident; and the effect was nil. Mrs Nisbett was accustomed to deliver the lines close to the footlights, with eyes fixed on the audience; and at the close would cross from left to right, and back again, cracking her whip as she did so. The effect was electrical. All honour to the exponents of the modern realistic school of acting; but dramas written under different conditions must be acted in a different manner" (vol 2, p 36). Likewise, Fitzgerald (1875) complained of another lack in acting ability relating to this play. Boucicault's "earliest pieces reflect the tone of the good old school of character, and his comedy of 'London Assurance', with its extraordinary vivacity, its unflagging diameter, its Dazzle and Lady Gay Spanker, which, in the cant phrase, act themselves, will never be dropped out of the list of acting plays. Yet a single fact in connection with this play should have warned existing actors of the hopeless incapacity into which they have drifted. Not long since a performance of 'London Assurance' was given, in which was combined, for some charitable benefit, the strength and flower of every company in London. The list of names represented all the acknowledged chiefs in the respective walks. Yet the failure was disastrous- more disastrous from the very pretension. The actors seemed not at home in such old-fashioned parts. Their line was the imitation of extreme eccentricities; they had lost the famous old art of getting within the mere rind of a character, possessing themselves by study of the key-note, the leading principle, which would, without effort, supply the true illustrative accompaniments of voice, gesture, and oddity" (pp 21-22). When Courtly “discovers that Lady Gay Spanker has only been pretending a willingness to elope with him...[he] comes to with a shock of self-understanding...He does not resent, belittle, deny, or counterattack the world, but accepts it as censor and judge, it is not conscience or principle or some private imperative that moves him, but the awareness of the world as laughing observer and voice of common sense that stirs his resolve to be wiser” (Heilman, 1978b pp 42-43).

"The octoroon" is based on a novel by Mayne Reid (1818-1883), "The quadroon" (1856) in which "Aurore, the quadroon or [one-forth] mixed-race slave of the Creole planter Eugenie Besançon, holds an almost mystical attraction for the hero and narrator, a European in Louisiana. Aurore has to be sold and almost falls into the hands of a schemer, who intends to dishonour her, but Besancçon manages to save her, and at the end of the novel, it is implied that Aurore and the narrator marry” (Meer, 2009 p 86). “Boucicault fashioned his plot from a novel by Mayne Reid, ‘The quadroon’, although his reworking of the story is considerable [including transforming the quadroon into an octoroon]. A secondary source was the contemporary novel, ‘The filibuster’, by Albany Fonblanque, from which the dramatist took the plot device of the incriminating photograph...The play is redolent of antebellum Louisiana life; both its white and black characters are presented with considerable realism. Dora Sunnyside, Salem Scudder, and Mrs Peyton are quite sympathetic, and the several scenes with the ‘niggers’ of Terrebonne offer an idealization of the slave-master relationship that is genuinely charming and frequently touching...The villainous Yankee, M’Closky is counterbalanced by the noble Yankee, Scudder, just as the evils of slavery are mitigated by Mrs Peyton’s genuine devotion and protective concern for her slaves. One of the most moving scenes of the play finds old Pete, the black patriarch, pleading with the other slaves to look their best at the auction, so that Mrs Peyton will be proud of them” (Vaughan, 1981 pp 125-131). It is "a very effective drama based on a subject which at that time, just before the Civil War, was one of burning reality: the condition of negroes and half-castes in the Southern States. It is the tearful love story of a half-caste girl, unoriginal in theme and plot; the originality lies in the diplomacy with which Boucicault managed to make his public sympathize to some extent with all the parties involved—the Puritan business men of the north, the upholders of slavery in the south, who were not without human feeling, and finally the poor negroes and above all the unhappy heroine. It was, however, a very important dramatic production, with an entirely American subject, and it prepared the way for later works of Boucicault and others” (Pelluzzi, 1935 p 244). The "characters spoke in favour of the south, while the story went against it. When the old negro, just before the slave sale, calls his coloured 'bredrin' around him and tells them they must look their best so as to bring a good price for the 'missis', sympathy was felt for the loving hearts of the South. When people realized that the darky was a slave, they became abolitionists to a man. When Zoe, the loving octoroon, is offered to the highest bidder, and a warm-hearted Southern girl offers all her fortune to buy Zoe and release her, the audience cheered for the South. When she was bartered for, they cheered for the North" (Disher, 1949 p 253). “Zoe may be black by race, but her fair skin has resulted in her being treated, almost, as white. She is not required to fulfil the normal role required of a black slave and has been excused from the normal labour function of her race...Zoe is an outsider, excluded from one community by her mixed race and from the other by the fact that she appears to be a lady and does not work...The law of the land contributes to Zoe’s outsider status as the miscegenation laws in Louisiana will not allow a marriage between her and George. Her parentage prevents her from marrying a white person and her skin colour and upbringing prevent her from marrying someone of her own race” (McFeely, 2012 pp 11-12). Though implicit, the play may be interpreted to end “with the promise of George and Zoe united in matrimony, (Merrill and Saxon, 2017 p 137). "Boucicault was in the habit of writing his dialogues. He possessed the art of making his interlocutors speak in character, and sometimes he devised remarkably fine, because dramatically, rather than verbally, expressive stage business and effect; as, for example, in the ingenious daguerreotype incident of The Octoroon" (Winter, 1908 p 133). "Photography doesn’t just work in the service of what Scudder calls a 'higher power', it represents and materializes a power literally above the law—acting as 'eye' and judgment of the 'Eternal' and as an extension of the audience’s judgment. In representing the camera as an instrument of divine justice, Boucicault aligns the technological with the supernatural...Photography’s seemingly extra-theatrical, transcendent evidentiary force and divine role leave little room or need for the photographer in The Octoroon. The only successful picture taken is the one in which no one is operating the camera- the photograph that would catch McClosky red-handed, standing over Paul’s lifeless body. Scudder’s technologically impossible self-developing plate only emphasizes photography’s transcendence further. Boucicault presents us with the spectacle of photography without photographers- a fantasy of automation in the age of mechanical reproduction. Scudder’s description anticipates the disembodied 'eye of the Eternal' of our current surveillance society" (Novak, 2016 pp 44-45). Pocock (2008) argued that “while Scudder's sudden zeal to convict could be attributed to his faith in the new-found photographic evidence, it must be recalled that the evidence against Wahnotee was at least as damning. His sudden shift seems rather to be motivated by a desire for revenge against McClosky for his financial exploitation of the Peytons and his purchase of Zoe- a noble enough sentiment for melodrama, but one that sits uneasily on the judicial stage. The duplicity of his rhetoric is underscored by his reference in both speeches to the ‘hearts’ of the jury: in the first, the all-white jury's eagerness to lynch the Native American Wahnotee makes them 'a circle of hearts, white with revenge and hate, thirsting for his blood', while in the second, their desire to execute McClosky reveals that they hold the law in their ‘real American’ hearts. If the law is, as Scudder asserts, located ‘in the hearts of brave men', it exists in a volatile variable medium, as subject to fits of white-hot rage and bloodthirstiness as to intuitions of honesty and truth. Scudder's orchestration of the impromptu trial ultimately achieves the equilibrium of the melodramatic stage: the villain receives a painful death as punishment for his crimes. Yet from a judicial standpoint the trial is a spectacular failure, leading not to a legal execution, but to a revenge killing” (pp 559-560). As in "The octoroon" and for much much of his career, Boucicault adapted material from other sources. He "possessed such a high degree of understanding of stagecraft that he was able to alter everything he took to make it better" (Fawkes, 1979 p 101).

"London assurance"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1810s. Place: London and Gloucestershire, England.

Text at https://archive.org/details/londonassurance00assogoog https://www.archive.org/details/londonassurance00boucgoog

Sir Harcourt Courtly intends to marry Grace Harkaway, niece of his old friend Max Harkaway, a squire. "I am about to present society with a second Lady Courtly; young blushing eighteen; lovely! I have her portrait; rich! I have her banker's account; an heiress, and a Venus!" he gushes. But Harcourt is unaware of the extravagances of his son, Charles. While Charles recuperates from a drinking bout, Sir Harcourt thinks of him as: "a perfect child in heart-a sober, placid mind- the simplicity and verdure of boyhood, kept fresh and unsullied by any contact with society." Misled into thinking of him as a family friend, Max invites Dazzle, a parasite, to his mansion, accompanied by Charles under the assumed name of Augustus Hamilton, who is struck by love at first sight with Grace, though she herself is rather cool towards him. "It strikes me, sir, that you are a stray bee from the hive of fashion," she says. "If so, reserve your honey for its proper cell." Dazzle is glad to tell Max that he considers himself "splendidly quartered" where he is. Max next receives the visit of Harcourt. At the point of introducing the so-called Augustus to his own father, Dazzle convinces him to "deny his identity" altogether. Although Harcourt is stunned on seeing Augustus' features so like his son's, he is led to believe it is not he, but Grace remains unfooled. Nevertheless, Harcourt advises Max he should get rid of the two "disreputable characters". To his astonishment, Max learns that Harcourt has never seen Dazzle in his entire life. Dazzle does his best to keep Harcourt away from his betrothed while his son courts her. But when Grace's cousin, Lady Gay Spanker, arrives, Harcourt is immediately smitten by her, an enthusiast of hunting pleasures. "Ay, there is harmony, if you will," she acknowledges. "Give me the trumpet-neigh; the spotted pack just catching scent. What a chorus is their yelp! The view-hallo, blent with a peel of free and fearless mirth! That's our old English music- match it where you can." To Harcourt's disappointment, she admits to being married, though to a submissive nonentity. To help Charles in his courtship, Dazzle falsely insinuates to Harcourt that Lady Spanker is equally smitten with him. Alone with Augustus, Grace assures him she will never be Harcourt's bride. Encouraged by this piece of news, Augustus kisses her, a sight discovered by Lady Spanker, to whom he admits his true identity as Charles Courtly as well as revealing that his father has fallen desperately in love with her, which she answers with a scream of delight. After dinner, Grace complains of being excluded from men's company. "The instant the door is closed upon us, there rises a roar!" she exclaims, whereby Lady Spanker comments: "In celebration of their short-lived liberty, my love; rejoicing over their emancipation." "I think it very insulting, whatever it may be," Grace retorts, to which her cousin answers: "Ah! my dear, philosophers say that man is the creature of an hour- it is the dinner hour, I suppose." To Grace's further grief, Augustus suddenly leaves the house, but, to her surprise, returns as Charles Courtly announcing that Augustus has met with a road-accident. He rejoices to see her swoon, though she only pretends to, and then specifies that the man is dead: news, to his surprise, she accepts very calmly. Meanwhile, Lady Spanker makes a fool of Harcourt by pretending to love him. After finding out this seeming relation, a lawyer, Meddle, congratulates Spanker that his wife is about to elope. When both men mistakenly think they have caught the erring couple in the act, Meddle advises him thus: "Now, take my advice; remember your gender. Mind the notes I have given you." To protect herself, Lady Spanker assures her husband that the elopement was only Harcourt's idea and encourages him to fight a duel with him, which he reluctantly agrees to. Max reveals to his daughter that Harcourt has waived his title to her, which she, displeased at Charles' behavior, accepts fuming, but Lady Spanker is horrified at seeing Harcourt emerge safely from the duel and runs out frantically to look for her husband. Harcourt then assures Grace that the duel was interrupted by her uncle with no harm done. Angry at Charles, Grace now avers she would like to marry Harcourt after all, but a creditor arrests Harcourt as a consequence of his son's debts and announces that Augustus and Charles are the same man. Although Harcourt refuses to pay his son's debts, Grace generously accepts to do so and then asks for the father's blessing. One last thing disturbs the entire company: who is Dazzle? "I have not the remotest idea," Dazzle answers.

"The octoroon"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1850s. Place: Louisiana, USA.

Text at http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/46091 http://victorian.worc.ac.uk/modx/index.php?id=54&play=346 https://archive.org/details/representativea00quingoog

Back after a long time abroad in Paris, George Peyton settles at the Terrebonne plantation with his Aunt Nellie in the aftermath of her husband's death as an heir to the estate heavily encumbered with debts. The present overseer, Salem Scudder, informs him that the previous overseer, Jacob McClosky, profited from the overspending tendencies of his uncle to buy the best part of Terrebonne. Jacob wants more. He informs Aunt Nellie that her banker has died and the executors have foreclosed all overdue mortgages, so that Terrebonne is now for sale. Nellie cannot prevent it unless she can recover a debt owed to her husband from a company in England, for which she is awaiting news by boat-mail. Jacob approaches Zoe, Aunt Nellie's husband's bastard child to a slave woman, an octoroon (one-eight black) whom she nevertheless fondly takes care of. Jacob flirts with Zoe, but she ignores him. As he blocks her path, Salem steps forward knife in hand to force him away. But by secretly rummaging through Nellie's desk, Jacob discovers that Zoe was freed as a slave while there was a legal judgment pending against her master, so that the paper proving she is free is void. He pilfers the papers on his way out. Later, he overhears George declaring his love of Zoe. Although she points out to George she is an octoroon, it does not matter to him. After the couple leave, Jacob notices Paul, a black slave boy sitting on the mail-bag possibly containing overseas news for Nellie. The boy is waiting to have his picture taken by his Indian friend, Wahnatee, who takes the picture and then wanders off with a bottle of rum. Jacob kills the boy by striking him over the head with Wahnatee's tomahawk and then recovers Nellie's letter. When the Indian returns, he believes that the photographic apparatus killed Paul and so destroys it. Meanwhile, the plantation slaves, including Zoe, are up for sale and Jacob succeeds in buying her. When the planters discover Paul's body, they infer that Wahnatee murdered him, a view supported by Jacob, who acts as his accuser in a make-shift trial set up to lynch the Indian. However, the planters discover a photograph made just before the murder, Jacob standing over Paul with the murder weapon. As a result, Jacob is taken into the hatch of a moored ship, but then frees himself from his captors. He next throws a lighted lamp on turpentine barrels so that the ship catches fire. Ready to escape, his flight is impeded by Wahnatee, who stabs him repeatedly.

George Colman the Younger

[edit | edit source]

Another celebrated comedy includes "John Bull, or The Englishman's fireside" (1803) by George Colman the Younger (1762–1836).

The play “extols the traditional English values of hearth and home. Colman's approach is to construe general moral values and, more specifically, the ideal English national character in domestic terms. Having a contemporary Cornwall locale, with settings in a public house, a manor house, and a brazier's shop, John Bull deftly contrasts values of city and country by presenting a range of characterizations clearly associated with one or the other. Students of the drama performed over the century-and-a-quarter beginning with Etherege and Congreve will perceive from Colman's comedy that a notable shift in social values has occurred. Tom Shuffleton, a city 'swell', and his eventual mate, the chic Lady Caroline Braymore, represent all that is deceitful and self-centred. They are city types, superior only in their temporary ability to gull certain country characters (Sir Simon Rochdale, the local magistrate, and Frank Rochdale, his son and a friend, he thinks, of Shuffleton) into believing them sincere. Shuffleton’s and Frank’s referents in character types help to illustrate the historical shift in social and ethical values embodied in the play. Earlier comedy frequently features a pair of vital young men, sharing attitudes and values which, though healthy enough, seldom inhibit their pleasures" (Donohue, 1979 pp 88-89). "Colman had studied...for the law, and the quarrel over the proper administration of justice is cleverly layered” (Thomson, 2006 p 188).

"The Englishman's fireside"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1800s. Place: Cornwall, England.

Text at http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/20177 http://www.readbookonline.net/title/48344/ http://www.archive.org/details/johnbulloraneng00ficgoog https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_tGStdo4OtEYC

After nearly drowning in a shipwreck, Peregrine arrives at the Red Cow Inn having nearly lost all his fortune acquired in India. On hearing a woman cry out, he rushes out but is unable to prevent the robber from taking all her money. Reluctantly, the victim, Mary, reveals she was on her way to ask money from her plighted lover, Frank, who has impregnated her but left her to marry a richer woman. "As soon as day broke," she explains, "I left the house of my dear father, whom I should tremble to look at, when he discovered my story, which I could not long conceal from him." Having heard of Frank's village love, his father, Sir Simon, baronet, requests his son's friend, Tom, to dissuade him from that purpose, offering money under cover of a loan. Frank receives a letter from Mary, describing details of her miserable condition. He is tormented for having abandoned her, but wishes to obey his father. Tom suggests he provide her with an annuity. "An annuity flowing from the fortune, I suppose, of the woman I marry!" Frank sarcastically exclaims. "Is that delicate?" "'Tis convenient," Tom replies. Meanwhile, Peregrine visits a benefactor from his boyhood, Job, a brazier in the midst of bankruptcy after being robbed by a friend. Peregrine offers Job money to prevent the seizing of his goods, but he refuses. Having found out Job is Mary's father, he finally convinces him to accept the money and thus restore his daughter's condition. When Tom meets Frank's intended wife, Lady Caroline, he woos her for himself, then delivers Frank's letter to Mary, who swoons on learning he will see her no more because of "family circumstances". Peregrine treats Tom roughly after learning of his intention to send her to a disreputable woman during her pregnancy. When Job and Mary unite, Peregrine reveals his intention of requesting Sir Simon, as justice of the peace, to force Frank to marry her. Peregrine then confronts Frank with the same purpose. "Marry her!" exclaims Frank, "I am bound in honor to another." "Modern honor is a coercive argument," Peregrine replies, "but when you have seduced virtue, whose injuries you will not solidly repair, you must be slightly bound in old-fashioned honesty." When Mary confronts Frank, he becomes at last convinced to follow this course. "I- I am almost glad, Mary, that it has happened," he admits. "When a weight of concealment is on the mind, remorse is relieved by the very discovery which it has dreaded." For his part, Job confronts Simon, but is met by a solid wall of refusal and a threat to arrest him for abusing a justice of the peace, at which Peregrine ushers the angry Job out of the room. But Simon's wedding plan on behalf of his son is thwarted after discovering that Caroline married Tom. He is at last forced to accept his son's marriage to a mere brazier's daughter after finding out that Peregrine is his own long-lost older brother and so the entire estate now belongs to him, as well as the treasure recovered from the seas. Job turns to Frank. "I forgive you, young man, for what has passed," he declares, "but no one deserves forgiveness who refuses to make amends when he has disturbed the happiness of an Englishman's fireside."

Douglas William Jerrold

[edit | edit source]

A notable melodrama of the period is "Black-eyed Susan" (1829), written by Douglas William Jerrold (1803-1857).

“The production of Edward Fitzball's The Pilot (1825) gave an impetus to the development of a native melodrama by its realistic pictures of the British tar and the glorification of the Union Jack. Buckstone's Luke the Laborer (1826) and Douglas Jerrold's Black-eyed Susan (1829) established a form of English melodrama with an original story, British characters, and considerable local color” (Tolles, 1940 p 22).

"Owing but its title to Gay's long-popular song, Sweet William's Farewell to Black-Eyed Susan, this three-act nautical drama renders a simply planned story in a dramatic fashion...The dialogue is neat, pointed, but on the whole natural, much of the lighter talk coming from Dolly Mayflower, the only other woman character, and her lover Gnatbrain, 'a half-gardener, half-waterman, a kind of alligator that gets his breakfast from the shore and his dinner from the sea'" (Jerrold, 1914 pp 116-118).

"No one can fail to observe the deliberate contrasts in Jerrold’s work, contrasts invaluable for dramatic purposes, the sorrow of Susan, and her struggles to keep a home above her head, exchanged for the joy of William’s return, the exhilaration of the reunited couple frustrated by the accident that makes of a brave sailor a condemned criminal. There is plenty of light as well as shade in the old Surrey drama...And yet...when I saw the play, I had to own that the tearful passages were overstrained; that the misery of the picture was too acute; that the agony was drawn out to a hysterical point; and that, although the taste of the whole thing from first to last was irreproachable, art was not quite satisfied" (Scott, 1899 vol 2, pp 145-146). "The decision of the court, Guilty, and the reading of the sentence, Death, were terrible blows to William's scores of friends before the footlights; and William's subdued 'Poor Susan' found echo in every sympathizing heart in the audience. The interest in the drama, however, did not reach its intensest point until the last scene of all the execution. The farewells with his shipmates and friends, the last dying gifts and bequests, and his parting from Susan, were all very harrowing, and very real, and very choking; but the culmination was William's standing under the yard-arm, his bare neck ready for the rope that was 'to launch' him, the parson on the black platform, the twelve melancholy-looking captains, the grief-stricken Admiral Leffingwell, and the entrance of Captain Crosstree with his pardon, and his honorable and explanatory speech" (Hutton, 1875 pp 155-156).

"No drama was ever more nautical; no other seamen so redolent of tar, so virtuous compared with landsmen, so full of seafaring oaths, exclamations, similes and metaphors- salt water is rarely out of their mouths and often fills their eyes. William never utters a phrase that is not seaworthy. Law is built of green timber, manned with loblolly boys; a woman makes more sail—outs with her studding booms— mounts her royals, moon-rakers and sky-scrapers. Several scenes show how constant Susan is despite her landlord, and how brave William is despite many smugglers. At length the plot begins when Captain Crosstree in his cups kisses Susan and is cut down by William. All is ready for the hanging from the fore-yard when Crosstree rushes forward with a pre-dated discharge ‘when William struck me he was not the king’s sailor- I was not his officer'" (Disher, 1949, pp 143-144).