History of Western Theatre: 17th Century to Now/French Post-WWII

Jean-Paul Sartre

[edit | edit source]

Jean-Paul Sartre followed up work from the previous period with "Les séquestrés d'Altona" (The condemned of Altona, more precisely Sequestered in Altona, 1959).

Sequestered in Altona "examines guilt: to determine where it begins, where it pertains, where (and if) it ends...This drama attempts to reconcile the life of conscience, of moral passion, with the simple fact that if any crime is pursued to its logical source, the criminal is not alone. There is always a reason, social or psychological or historical, behind every immoral act that leads back to another reason, and then back to others, away from the criminal himself. But, Sartre asks, if this is true, how are we to judge, as we must? How are we to know what good is? How are we to make life better, more bearable? The dramatic image that Sartre has chosen for his theme is striking" (Kauffmann, 2021, p 23). “Another preoccupation of Sartre’s which appears in ‘Les sequesters ‘Altona’ is the idea that the winner loses, and the loser wins. The father succeeds in seeing Franz only to discover that there can be no communication between them. Leni destroys the relationship between Johanna and Franz only to lose him altogether” (O’Connor, 1975 p 31).

“In the von Gerlach household...time has stopped, because of Franz...He never had to take the responsibility for decisive acts till one day at Smolensk when he tortured a partisan. He did so allegedly for his country’s sake but really to overcome a sense of impotence, affirm his independence of his father and manifest his personal power by a major act” (Jackson, 1965 p 64). “The characters are all perfectly aware that they are in bad faith and consciously choose to remain so...Bad faith consists in the substitution of a persona for personality to use...In Leni’s words...'Here, you know, we play the loser takes all’...She tries to make Franz face up to his past...She fails...[and] merely wants to act out her chosen role, she has no interest in effecting any change in the situation...Her attitude is summarized in her incestuous relationship...Leni has chosen to be...an unsuccessful rebel...[for] failure has only to be desired to be transmuted into success...Only if [Franz] maintains his self-sequestration can she use him as a weapon against her father in her nominal rebellion against all that the family stands for...The significance for Werner of Johanna’s relationship to Franz is that it is the final indignity, [which] depends less on Werner’s relationship with his wife than on the relationship of the two brothers to each other and to their father...He wants nothing better than to please his father...but he is constantly thwarted...Just as Leni and Werner choose to be failures, so does Johanna...Johanna’s wedding was the funeral of her quintessential beauty...However, she needs an audience for her martyrdom: Werner...The driving force in Gerlach’s life has been a belief in the rectitude of capitalist power...and [he] disregarded all normal objections to the nature of Nazi power...The justifiability of the capitalist way of life...is that there are no visible alternatives...[In suicide is] the possibility of choosing the manner of his own defeat...Why does Franz feel guilty about the murder and the torture?...[He] is disgusted because he was powerless to do anything else...He had conscience...but the dominant desire was for power...His plea is that the nature of the historical process is such that evil was the only possible result of human activity...He is implying his own guilt, and guilt posits freedom” (Palmer, 1988 pp 308-317). “Franz discovers not only his own unreality and impotence but experiences in an acute form the subjective state of being hammered into the ground. Only in one particular was he not a mere image of his father and that was when he used torture, so that death is the only means by which he can escape from an intolerable situation- the realisation that he tortured for nothing- and assert what little remains of his own reality” (Wardman, 1992 p 263).

"Frantz sequesters himself because of his past participation in war crimes and current participation in incest...Leni's love for her brother...thrives in the close atmosphere of her brother's more literal sequestration. It is to protect this intimacy that she has refused to be her father's messenger throughout the years. Leni is, moreover, aware that her love for her brother is part of her fanatical espousal of a certain code of tribal family life. 'Incest is my way of making family bonds tighter,' she says...Werner was born to jealousy. Rejected in favor of Frantz, Werner cannot give himself to any relationship unless it be an attitude of permanent courtship which he has adopted towards his father...The question is: why does he refuse to leave? He...is rooted in own conviction of inferiority...At first glance Johanna appears to be an energetic well-balanced woman, ready to fight for her husband...She is less an accomplice than the others and more of a victim...She has already progressed towards her own individual liberation...It is this that Werner does not understand in her and by his lack of understanding, he condemns her to the fictions which she has already abandoned...Old Gerlach had sequestered all...If he did so, it was because he himself is the greatest 'sequester" of all...His single ethical code was that the end justifies the means...He said of the Nazis: 'I serve them because they serve me...But they are fighting a war to find markets for us and I'm going to have trouble with them over a piece of land'...the source of Frantz's sequestration complex" (Pucciani, 1961 pp 23-30) "Fear was the only emotional rapport between the domineering patriarch and his children, and Johanna discovers that his incapacity of love caused the death of his wife. Rejecting his younger son emotionally and physically, the elder von Gerlach makes Werner the prime target of his sadistic humiliations. The same lack of sentiment sequesters him from the affections of his daughter" (Galler, 1971 p 179).

“The five characters exist primarily for Franz, whose sequestration has sequestered them as well...Gerlach’s collusion with the Nazis was based on the reality of Nazi power; to remain the boss was primary and to remain a boss during the war meant to collaborate with Hitler...When the play opens...Gerlach still owns the form but no longer commands it...Franz was conceived and raised to be just like his father, a boss, with his father’s pride and his father’s passions...For three years, his father has known that he was ‘the butcher of Smolensk’. Nevertheless, von Gerlach neither can nor wants to judge his son. Bound to Franz in whatever he is, von Gerlach rejects Franz’ acts but continues to love him totally. His paternal love, born of identity, makes judgment impossible. The identity of son with father is brought to its resolution when von Gerlach takes on Franz' responsibility for his crimes as butcher of Smolensk. Left with nothing, Franz allows his father to sanctify that nothingness” (McCall, 1969 pp 128-139). “Presumably, in Franz’ semi-lucid consciousness, the inhuman crustaceans [seen on the ceiling] represent the future inhabitants of earth, successors to a mankind that is about to bungle its last chance” (Parsell, 1986d p 1651).

"Frantz’ whole life has been falsified and his freedom robbed by his father’s choice to devote everything at his disposal, including his own children, to the creation of a vast capitalist empire” (Bradby, 1991 p 44). "The play's conclusion, in which father and son commit suicide by driving their Porsche off the Teufelsbrücke, points to the bankruptcy of the father's complicitous behavior and the son's ultimate moral impotence. However, the audience is also implicated because it is forced to listen posthumously to Frantz's pre-recorded speech- an analepsis created by a now dead protagonist but which is directed to the audience; yet another example of reaching back into the past to clarify the present and the future. In it, Frantz declares that 'this century would have been fine if man had not been pursued by his cruel, immemorial enemy, that carnivorous species that swore to destroy him, by that vicious hairless beast called man'. The play's final moments also share elements with 'The flies' (1943) and 'No exit' (1944). In a gesture similar to Orestes, Frantz assumes responsibility for this world and 'takes the century on his shoulders' while, as in the case of 'No exit', the play does not end abruptly. There is continuity...'Leni enters his room' and thus becomes the next prisoner of the von Gerlach enterprise, which will from now on be directed by Werner with the help of his wife Johanna (Van Den Hoven, 2012 pp 69-70).

Johanna “is the least sequestered of all, the most fearful of being a prisoner; she alone sees through sham, including her own former artificial identity as a movie tar. Werner, a fine physical specimen but weak in character, seems interested chiefly in trying to win from his father, tardily, the recognition he never received, as a younger son” (Brosman, 1983 p 95).

“Sartre’s play, one of his most complex if not his best, is marked by the extraordinary intelligence and eye for the crucial issues which are to be found in everything he writes. His theme cannot be stated succinctly; moving from morals to politics, from philosophical speculation to psychic inquiry, Sartre composes a new kind of tragedy, a black fable of human responsibility“ (Gilman, 2005 p 188).

"Sequestered in Altona"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1940s-1950s. Place: Altona borough in Hamburg, Germany.

Text at ?

After learning he has only a few months left to live, an industrialist, von Gerlach, wishes his younger son, Werner, to take over his boat-construction business. He also requests that Werner, his wife, Johanna, and his sister, Leni, remain together in their 32-room family mansion, watching over his eldest son, Franz, who has been kept sequestered in the house for thirteen years. Werner and Leni agree to do so, but Johanna wants to move elsewhere alone, so that the father must explain why the three should remain together after his death. In 1941, he received an offer from Goebbel, Nazi minister, to sell his field and organize a concentration camp for Jews, which he accepted. During the persecution of the Jews, Franz was caught harboring a rabbi inside his father's mansion. The rabbi was killed before his face by SS officers and Gerlach forced to send his son away in the march towards Russia. Johanna suspects that her husband tipped off the SS. In 1946, American officers were invited at the mansion, where Leni was in the habit of enflaming their desires and then dashing them with insults. One day, an officer attempted to rape her. She was able to defend herself by hitting him on the head with a bottle. To protect her from being persecuted for that deed, Franz took the blame, and, thanks to a deal with an American general, was allowed to go abroad, but instead stayed home in hiding. Johanna hates that story. She does not change her mind, delivering an ultimatum to her husband: either to stay or follow her elsewhere. Over the years, Franz has refused even to see his father, only allowing Leni to enter his room. Gerlach tries to convince Johanna to speak with Franz, at least to let him know he is dying. Franz is not the humanist he first appeared from his father's anecdotes. Wearing an officer's uniform in shreds, he keeps Adolf Hitler's picture in his room and peppers it with oyster shells. Since the end of the war, he considers the entire country overrun with weeds, passing the time either drunk or engaging in an incestuous relation with his sister. Johanna obtains Leni's secret code from her husband to see Franz. She reveals to him that his father is dying and that she would prefer to see him either free or dead than living in such a manner. After learning that Johanna succeeded in seeing Franz, Gerlach asks to see him, too, but she refuses to help him, thinking it might lead to his death. Werner thinks his father's purpose is to place Franz as head of the business in his place. Eventually, Johanna changes her mind and informs Franz about his father's wish to see him, but cannot entice him back to a normal life. "I will abandon at once my life of illusions....when I love you more than my lies, when you love me despite my truth," Franz declares. He specifies that his sequestration is due not by something he did, but by what he failed to do, in passively permitting a fanatic in his troup of soldiers to torture some civilians. His confession, spurred on by a Leni jealous of her rival, repulses Johanna. Neither Johanna nor Leni are able to convince Franz to leave his room. Yet at the moment when Johanna backs off from the mutual love they began to feel for each other, he accepts at last to see his father. Franz has read in the newspapers of his father's financial successes, he who has always played the game of "whoever loses, wins". Gerlach is surprised to learn that Franz accepts to run the business. While reminiscing about the past, Franz reminds him of the time when they once drove a car together at great speed, both wishing to relive that experience. When they go out together, Leni becomes certain that they will die together.

Henry de Montherlant

[edit | edit source]

Henry de Montherlant (1895-1972) followed up the previous period with another noteworthy piece in the tradition of a realist rendering of history, "Le maître de Santiago" (The master of Santiago, 1948).

In "The master of Santiago", "a father refuses to take any steps to secure his daughter’s perfectly honorable marriage to a man she loves, because he rejects all compromise with life in complacently prosperous and power-minded Spain after the defeat of the Moors. His daughter, stirred by her father’s extreme honorableness, puts an end to the hoax that would have secured him riches and that would have enabled her to marry. The father is a remarkably well-drawn Don Quixote (without any ludicrous attributes, however), and his aversion to the conniving world and the enslavement of the American Indians by Spain rises to truly heroic proportions. The flame of idealism in this drama is all-consuming. One could wish only that it also had more human warmth. The knight’s almost superhuman purity of motivation is, no doubt, intended as a slap in the face of ordinary humanity- for which Montherlant had perhaps too much contempt to become a truly great dramatist" (Gassner, 1954a p 724). The grand scale of the play “takes the form of a resistance, expressed in fine language, to anything vulgar, mediocre, commonplace” (Cruickshank, 1964 p 110).

“Don Alvaro, whose mission is to convert the Indians of the new world, scorns the efforts he directs…In the end, [Mariana] is persuaded that the institution of marriage is an obstacle to grandeur and to salvation: is this not the very reason why Catholic priests are not permitted to marry and why members of contemplative orders are closest to God?” (Cismaru, 1986 pp 1353-1354). “No wealth in the new world for him, no marriage and happiness for her! It is a total refusal, urged on by a kind of sadistic romanticism for purity...The master...is not an example of a model Christian, for his egoism, cruelty, and all his actions have a dreadful inhumanity...The love of Alvaro is a love of extermination; he has a hardness which is only explained by his pride” (Lumley, 1967 pp 345-346).

“Even at his best, [Alavaro] is only half a Christian...because the Christianity he has to apply is incomplete...He feels with great force the first constituent of Christianity, its unworldliness, its scorn of earthly comforts and riches, its renunciation, but of the sense it gives of union with God he is wholly ignorant...Now the religion of Alvaro a consists almost entirely...in a consciousness of the infinite grandeur and distance of God…But the Incarnation? The tender union with Christ on the cross?...These things remain outside of Alvaro’s experience...The truly Christian character...is...Mariana, who eventually sacrifices herself in order to share his renunciation of the world“ (Hobson, 1953b pp 179-181).

“To many, Montherlant’s ‘Christian’ drama may appear to be the study of fanaticism devoid of saintly qualities, the sort of fanaticism that stops far short of godliness and is, at best, a narrow reaching beyond the self...Don Alvaro expresses a wish to isolate himself from all worldly commerce and concerns into a carefully planned isolation for the sake of contemplation, and to gain salvation...The world has become too much for him, he does not understand it, and he ceases to want to understand it...Mariana is depicted as an obstacle forever standing between her father and God. Her father has no interest in guaranteeing Marina’s happiness by permitting her marriage...The institution of family is condemned...The Order is the real family of elected spirits with common beliefs and noble concepts. It does not impose attachments...Mariana’s serious statement that she does not wish to be happy prepares the way for an eventual understanding with her father...The father uses the cape to cover both his shoulders and his daughter’s in a gesture meant to underscore their ecstasy and their oblivion- or else their madness and their surrender of life” (Johnson, 1968 pp 110-113).

"The master of Santiago"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1519. Place: Avila, Spain.

Text at ?

Members of the Order of Santiago meet at the house of their master, Don Alvero. Three of its members decide to try their fortunes in the new world. To Alvaro, the present times are rotten, compared to the famous times when Spain ousted the Mores from Spain at the battle of Granada, when he "contemplated God in his cloak of war". The supposed purpose of converting Indians in the new world is "impurity and excrement", because the passion of lucre, instead of sending Indians to heaven, sends Spaniards to hell. When his friends leave, Alavaro rejoices in his solitude. "O my soul, do you still exist?" he asks himself, "O my soul, at last you and me!" A friend, Don Bernal, has heard about the love-match proposed between his son, Jacinto, and Alvaro's daughter, Mariana. Because of Jacinto's expensive mode of living, Bernal suggests that he enrich himself along with others in the new world, a plan the master immediately and irrevocably refuses. Alvaro is not interested in acquiring money even for his daughter's sake, whom he best loves in the world. "You will not steal my poverty," he warns his friend. He harshly accuses his daughter of dishonesty in this matter, calling love "monkeyshine". "Is the father of a daughter a father?" he asks himself rhetorically. In an attempt to help the young lovers, Bernal asks the count of Soria to mislead Alvaro into thinking the king commands Alvaro's presence as an administrator in the new world, but Mariana, unable to deceive her father, ruins the plan by admitting the deception to him. Fed up with world affairs, Alvaro heads towards St Barnaby's convent, a place where Mariana can live, too. She accepts the offer. He covers her with the white robe of the Order of Santiago, and, with the snow falling outside, father and daughter seem ready to live buried in mystical snow.

André Gide

[edit | edit source]

Another play based on a religious theme but in a more critical vein is "Les caves du Vatican" (The Vatican cellars, 1950) by André Gide (1869-1951), a close adaptation of his 1914 novel of the same title. The story derives from a historical event in 1893 (Ireland, 1970 p 252) when “a crooked lawyer, an unfrocked nun and a scandalous priest conspired at Lyons to spread the rumor that Leon XIII had been imprisoned by Freemason cardinals who had substituted a false pope in his place, and collected money from the faithful for his release” (Painter, 1968 p 67). The following critiques concern the novel, but is equally valid for the play.

“There are two main plots...the story of Lafcadio and the story of the conspiracy...linked by the relationship of the family...[The objective of the] Vatican swindlers...is to make a fool of society” (Painter, 1968 pp 66-67). “A pope on earth should, by definition, be a repository of infallible truth, divinely guaranteed. But of course the authenticity of the pope would, in turn, require to be guaranteed: one could have confidence in the infallibility of the pope’s pronouncement only if one could be infallibly certain that one is dealing with the one infallible pope” (Ireland, 1970 p 270).

“Protos divides humanity into two types: ‘the subtle’, to whom of course Protos belongs, are those whose Protean sensibility dictates a flexible and variable response to any given situation, those who, for whatever reason, do not present the same face to all people and in all places; they are the enemies of ‘the crustaceans’, the rigid, the insulated, the men of principle to themselves in all contexts...Protos...takes in all the aristocratic and bourgeois crustaceans...is the embodiment of escape- escape from society...one's self...one’s past, of evasion in its wildest Gidian sense, and in the sense of the perpetual mobile unrest of the creative spirit...Julius...is a novelist whose failure is due to the excessive logicality of his characterization...Lafcadio [is] turbulent and voluptuous [but] has imposed upon himself an austere discipline of self-control...to the extent of inflicting...penitential and admonitory stabs with a pen-knife for the slightest lapse in self-restraint” (Thomas, 1959 pp 157-161). “Lafcadio, a youthful vagabond...is both beautiful and amoral” (Pollard, 1991 p 365). Lafcadio’s “natural elegance and superior attainments make him a misfit in the lower classes of society, while the circumstances of his birth and the modesty of his condition exclude him from the higher” (Ireland, 1970 p 262). Each of the crustaceans, Julius, Anthime, and Amadeus, “changes his thoughts and habits, uprooting himself from all his past”, but, being crustaceans, lapse back to what they were (O’Brien, 1953 p 180).

Different though partially overlapping views have been presented on Lafcadio’s motive for murder, a seemingly gratuitous act. As a bastard, Lafcadio’s “unconscious need for recognition and parental love- it is irrelevant that he is too far gone to know what to do with them if had had them- has turned to equally unconscious need for revenge. In the mediocre bourgeois image of Fleurissoire, he pushes overboard the society that had rejected him” (Painter, 1968 p 72). “In ejecting Amadeus, Lafcadio was rebelling not only against the deeply rooted, intricately ramified family and the whole regime of the hard-shelled crustaceans, but also by implication against Wagner and Parsifal and all those who have made a cult of them...Lafcadio is a temperamental gambler who loves to play with sensations and emotions” (O’Brien, 1953 pp 185-186). He is narcistic, “eager for self-knowledge...deriving from a frantically impatient insensibility, a consuming lust for sensation of the most intense” (Thomas, 1959 p 162). “Bored and intrigued by his companion, Lafcadio allows his imagination to wander...It is precisely [the] apparent lack of motive that the interest of the proposition lies...It is about himself that he is curious” (Ireland, 1970 p 263).

"The Vatican cellars"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1890s. Place: Italy.

Text at ?

Anthimus, an atheist and a cripple, is angry at his wife, Veronica, for offering votive candles to the Virgin Mary meant to improve his health. To his surprise, alone in the dark, he hears the Virgin's voice and becomes cured, joyfully throwing away his crutches and converting himself to the Catholic faith. Anthimus' wealthy brother-in-law, Julius, a writer, is requested by his dying father, a count, to visit the father's bastard son, a youth named Lafcadio, whom he has never met. To obtain information on Lafcadio, Julius proposes him some work as a secretary. In his will, the father bequests to Lafcadio a large sum of money provided he promises not to bother other members of the family with his presence, so that he need not take the job offered him by Julius. On his way to Julius' house, Lafcadio saves two children from a house on fire, to the admiration of Julius' daughter, Jennifer. Lafcadio's description of his life-history to Julius is interrupted by news of the count's death. Meanwhile, Julius' other brother-in-law, Amadeus, hears a rumor that Pope Leo XIII has been abducted and kept in a dungeon at San Angelo's fortress, annexed to the Vatican, while an imposter takes his place. The rumor is false, perpetrated by Protos, a school-chum of Lafcadio, to obtain large sums of money from gullible Catholics for the purpose of freeing the pope. When Amadeus arrives in Rome, Protos, disguised as a priest, befriends him and takes him to Naples to an associate in crime, Bardoletti, pretending to be a cardinal, who requests him to change a bond of 6,000 Francs into ready cash. At the same time, Julius is also visiting Rome to request the pope a compensation for the loss of revenues suffered by Anthimus, no longer protected by freemasons he once counted on in his career. However, he is unsuccessful at this task. Amadeus reveals to him what he knows about the missing pope, but Julius finds it dificult to believe such a story. Nevertheless, he helps him retrieve the money from the bank and gives him a train ticket in his name. By coincidence, when Amadeus takes the train from Rome towards Naples, he encounters Lafcadio, neither knowing each other. Bored with his life but willing to dare fate to the utmost, Lafcadio throws him out the door to his death. He takes with him Amadeus' train ticket but not the 6,000 francs. While meeting Julius in Rome, Lafcadio is surprised to learn that the murdered man is Julius' brother-in-law. To tease his half-brother, he leaves on the table Amadeus' train ticket. On discovering this, Julius becomes extremely worried he may become the unknown murderer's next victim. Unknown to Lafcadio, his murder was observed by Protos, who proposes to his old friend that they blackmail Julius. Lafcadio refuses and discloses his crime to Julius, a conversion overheard by Jennifer. The murder makes her love the man even more. Lafcadio makes off with her, concluding: "Together, we'll know how to save ourselves."

Jacques Audiberti

[edit | edit source]

A bridge links Jarry's "Ubu the king" (1888) with Dadaist and Surrealist movements of the 1920s and the Theatre of the Absurd of the 1950s. An example of a Dadaist play is Tristan Tzara's "The gas heart" (1921) where nonsense prevails. Examples of Surrealist plays include "Victor, or the children come to power" (1928) and "The mysteries of love" (1927) by Roger Vitrac. The playwrights of both movements seek to overthrow middle class conventions with dream images. Surrealists show interest in replacing dominant conventions with a new society, including a communist one, whereas Dadaists show little desire to replace them with anything. A bridge also bonds existential drama and the Theatre of the Absurd in Jacques Audiberti's (1899-1965) "Le mal court" (Evil runs, 1947), also showing affinity in the past, including Georg Büchner's "Leonce and Lena" (1836) and Alfred de Musset's "Fantasio" (1834).

In "Evil runs", "the plot and the themes are deliberately conventional, bathed in the glow of fairy tale magic. The characters mostly bear functional names...and are devoid of psychological substance. They tend to talk in abstract terms...but their make-believe world is never troubled by doubts or questions from outside” (Bradby, 1991 p 188). "The plot is unimportant in itself, serving only to illustrate the theme, which is that of the omnipresence and inexorable force of evil. Audiberti uses a conventional fairy-tale plot: beautiful young princess, daughter of an impoverished king, goes to marry rich young king; wicked cardinal intervenes and prevents marriage for political reasons; beautiful young princess heartbroken, etc...Audiberti carries his classic fairy-tale formula only up to a point: the rich young king does not throw the wicked cardinal into an oubliette so that he can marry the beautiful young princess at the end. Instead, the princess, Alarica, finds as the play proceeds that she is and always has been ringed around with evil and deceit. Her illusions about the goodness of life and the decency and trustworthiness of people drop from her one by one in a series of painful shocks. She discovers that her projected marriage has been secretly abandoned a long time ago and that she is being used as a decoy so that the young king can make a politically more advantageous match. Even her old and faithful nurse is in the plot. There is absolutely nobody she can trust. Everyone is self-seeking, corruptible, and dishonest because everyone is living and ordering his life within the context of an artificial and corrupt society. As the series of shocks which she is obliged to undergo bludgeon her into an awareness of the true nature of the world, Alarica realizes that she must make her compromise with it if she is to survive as something other than a pawn. She determines to fight evil with evil- to let 'the evil run'. She deposes her amiable, bumbling old father, disregarding his pleas for filial respect, and resolves to rule with complete ruthlessness. If everything is evil, then the most evil wins" (Wellwarth, 1962 p 336).

"Evil runs"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1940s. Place: Fictional country of Shortland.

Text at ?

Alarica, princess of Shortland, must marry for political reasons Perfect, king of Occident. She hears a knock at the door and a voice stating that the king has arrived. While the princess and the supposed king confer, her lieutenant discovers that the man is an imposter. As the intruder, Ferdinand, tries to leave, the lieutenant shoots him but lets him live. While Alarica and her governess discuss the case, a second knock is heard, stating once again that the king has arrived. This time it is the genuine king, who finds the princess attractive, but the cardinal in his company reveals that their marriage prospects have been annulled, as it is more in their country's interest for the king to marry the Spanish king's daughter. "We will marry Spain and make her pregnant," the cardinal affirms. However, during his absence, the king proposes marriage to Alarica and is accepted. They set off for Occident, but when the subject of what to do with Ferdinand arises, Alarica proposes that he share their bed. The king is stunned at this suggestion and no longer knows what will become of him. Although Alarica and Ferdinand sleep in the same bed, they find it difficult to agree. "All that you deserve is for me to let you wade among your ideas like a comb in soup," he says. Meanwhile, the king of Shortland, Celestincinc, demands to know what a stranger is doing in his daughter's bedroom. She behaves more and more strangely to the point that Celestincin suspects his daughter has gone mad. "Evil runs. A ferret! A ferret! At all costs let it run," she says. Celestincinc orders Ferdinand's arrest. Alarica disapproves of this decision. Her life has only served so far to "mask the present tornado of my ferocity," she says. Inspired by Alarica, Ferdinand proposes great improvements in the land of Shortland, to the astonishment of the marshal, who finds his plans "totally prodigious". Alarica proposes that the lieutenant and the marshal abandon fidelity towards her father and submit themselves entirely to her and her husband as queen and king of Shortland. They agree. "Evil runs," Alaracia happily concludes.

Arthur Adamov

[edit | edit source]

Arthur Adamov (1908-1970) is another Surrealist playwright with a claim to fame, especially in presenting the problems of a writer in "L'invasion" (The invasion, 1950).

“At the very least we can say that Pierre's life, and to a lesser extent the lives of the others, is invaded by the indecipherable legacy of Jean. There is a real question, however, as to whether Jean even knew what he was writing. Thus it seems to me that we are entirely justified in seeing the manuscript as a symbol of the undiscernable meaning which invades life at its core...Pierre thus becomes a type of the modern man who is caught in the task of trying to discover the meaning of life, which remains obscure, and who is at the same time unable to leave off the struggle. Pierre's strategy is to forsake all communal efforts and pursue a kind of ascetic way alone. His personal quest thus takes on much of the character of the religious quest which is pursued in hermitic isolation. He refuses to speak to anyone while he is alone in his room apart. His mother brings his food on a tray but does not converse with him...Agnes' presence always represents possibilities for renewal. In the first scenes she is the one who works at the typewriter, an instrument of communication. The room is messy when she is around but the feeling is one of creative possibilities within the mess. However, as Pierre increasingly withdraws from his relationship with Agnes, these possibilities are reduced. Agnes' sexual significance is then transferred to the first man who comes along when Pierre retires into isolation, and Agnes leaves with her new man. We learn when she comes back for the typewriter that the first man who comes along has taken sick, and she is left with trying to hold his business together. Thus, perhaps, disintegration as well as renewal are symbolized in her, but so far as her relationship to Pierre is concerned renewal remains a possibility. Such a possibility is underlined when Pierre comments to his mother at the end that if only Agnes had had more patience, the two of them could have made a new beginning on the manuscript, an April renewal if you will. But this possibility had been finally frustrated by the mother, and Pierre's doom is sealed" (Sherrell, 1965 pp 401-403).

“Pierre, Agnès and Tradel, their friend and collaborator, are in disagreement among themselves and unable to achieve a collective resingularization that would enable them to effectively resist the invasion of the mother and her accomplices...The mother is an invader. She takes up residence in her son’s apartment and gradually imposes her own standards of order upon it...The room is neatly ordered and immigration has been stopped. As the scene progresses, Pierre disappears to his room and dies alone. Whether he commits suicide or not is unclear, but by encouraging Agnès’s exit and then blocking her return, The mother certainly contributes to his death...Pierre, Agnès and Tradel are unable to connect and devise a strategy to resist the conservative forces because they do not appear to realize their shared interests. The audience can see the power grab of the mother, but it is not visible to those who will suffer most from it” (Chamberlain, 2015 pp 154-155).

“The dead man’s papers represent for Pierre both an occupation and a search for meaning, despite ironic suggestions throughout the play that there may well be less to Jean’s legacy than meets the eye…Agnès herself appears to stand for disorder; it is, after all, through her that Pierre has become involved with her brother and his papers...The Invasion casts serious doubt upon the validity of work, as well as that of love and friendship; such, Adamov seems to be saying, is the eventual result of all human endeavor: futility” (Parsell, 1986a p 15).

“The Invasion stresses the relative nature of truth in a world wherein absolute truth is impossible to attain. The title refers to an unfinished manuscript which intrudes into the life of the family and friends of its deceased author. The laborious struggle of these people to decipher the handwriting and clarify the work ends in a dismal stalemate for, in addition to disagreeing among themselves, they individually find different interpretations for each word until no one is certain of the real meaning” (Bishop, 1997 p 56).

"There is wide disagreement about the transcription and meaning of certain key passages. Pierre’s struggle to put his friends work in order fails; he loses his wife, his friends and even his own sense of identity in the process...Pierre’s crisis occurs when he can no longer feel the living force of language...When he says that language has lost the quality of spatial existence, he is saying that thought is no longer possible and hence that his very existence is in jeopardy” (Bradby, 1991 pp 83-84).

"The invasion"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1950s. Place: France.

Text at ?

Peter works hard in trying to decipher writings left by the dead brother of his wife, Agnes. While he slowly makes way in assembling the texts, she types them up. They are helped by a friend, Tradel, but the two men do not agree on the best method of proceeding. Peter believes in obtaining the most accurate word-for-word version, while Tradel believes in obtaining an approximate version completed by their instinctive knowledge of what was meant. Because of this disagreement, Peter works alone, though Tradel warns that they must hurry, because the dead friend's family is seeking legal means of obtaining the documents for their own use. Peter thinks they can do nothing about that. An unknown man shows up to buy the apartment next door. The stranger takes pity on sad-looking Agnes, almost totally ignored by her preoccupied husband. Unable to pursue his work, Peter decides to quit for awhile and live inside a secluded room in their apartment, to be bothered by no one. "I will not have peace so long as things do not show a certain perspective," he affirms. Agnes and Tradel do not believe this to be a good idea. Peter's mother will bring him meals as usual, but he warns her never to utter a word to him. With Peter ensconced in the little room, the stranger loses no time in declaring his love to Agnes. They go off together, to the amusement of Peter's mother, who laughs and slaps her thigh at this event. When Peter emerges from the room, he is ready to assume an ordinary life. He tears the papers he spent so much time on and then learns his wife has left him. He expresses understanding of her decision in view of their disordered life together, but his mother blames her for the disorder. As he leaves the room, Tradel returns to reveal that Agnes' family is ready to remove the papers from off their hands, but then discovers all of them torn up. Unexpectedly, Agnes comes back, but only temporarily, since her friend is sick. After brief exchanges, the mother pushes her out. When Tradel looks for Peter, he discovers him dead. "I will never forgive myself," he declares. The mother is stunned at this event and stands immobile.

Jean Genet

[edit | edit source]

Another main dramatist of this period is Jean Genet (1910-1986) with "Les bonnes" (The maids, 1947) and "Les nègres" (The blacks, 1958).

“The opening of The Maids is one of the most brilliant scenes of the contemporary theater. Dispensing entirely with exposition, it plunges us straight into the heart of what we will eventually understand to be a ritual enacted regularly by two servant sisters. Initially disconcerted by the bizarre behavior of a mistress and her maid, the spectator discovers the stylized game of domination that links them…The sisters’ daily excursion into structured fantasy is their way of surviving their stifling reality. Their staged revolt against ‘madame’ relieves them of the necessity of revolting against the real ‘madame’...The fact that the real ‘madame’, when we see her midway in the play, is clearly not the tyrant the ritual makes her out to be changes nothing in the maids’ perception. Their need to revolt is real, but their desire to revolt is undermined by their fascination of ‘madame’. Thus, they content themselves with a mock revolt, aimed as much at one another as at ‘madame’, a stylized enactment of revolt deliberately circumscribed to end just short of murder” (Bishop, 1997 pp 125-127). From the start of "The maids", Solange plays her mistress' role as “domineering and insulting...The response of the maids to madame is ambivalent, a compound of hate and affection, of envy and admiration, with hate and envy predominating...The dramatic conflict in ‘The maids’ is between the condition, status, or role of servantdom and that of madamedom“ (Jacobsen and Mueller, 1976 pp 138-143). "The two maids are linked by the love-hatred of being each other's mirror images...At the same time, in the role of the lady, Claire sees the whole race of servants as the distorting mirror of the upper class. Thus what they hate seeing reflected in each other is the distorted reflection of the world of the secure masters, which they adore, ape, and loathe" (Esslin, 1974 p 174). “The dramatic dialogue at first appears strangely directionless– they just seem to be talking about themselves, their situation and how they want to change it– but the audience gradually begins to understand the dramatic drive underlying their discussions: they are trying to talk themselves into a state of transformation where they can escape their constricted existence and become what they are not: free agents. For in Genet’s theatre, the function of representation is not to show the world as it is, but rather to show the exaggerations and distortions through which our imaginations try to construct the desired image of ourselves and the forces that shape those imaginary selves...The maids’ repeated protestations of devotion to madame can be seen to be the product of their desperate longing to share the existence that is hers, rather than the expression of simple human affection. They are painfully aware of how Madame patronizes them and treats them just as it suits her changes of mood, with no consideration for their feelings, but they still see that her existence is deeply desirable, relative to theirs” (Bradby and Finburgh, 2012 pp 35-36). "Because they hate their place so much, they also hate each other and themselves. As Solange says, ‘grime does not like grime’. The servants fail in their quest because of this hatred. As Malraux and Sartre mentioned, 'revolutions are possible only when the victims of oppression can look upon their present condition as a possible source of future dignity'...Solange and Claire have no alternative value to offer...They would like to possess madame’s qualities themselves, and although their fury at being unable to do so may express itself in dreams of murder, they finally only punish themselves” (Thody, 1968 pp 165-167). “When madame arrives, she is not the ogre we have been expecting, but a fairly ordinary, rich, over-romantic, superficial woman of the world...Claire now realizes that their first move against madame must be to kill in themselves the elements of madame they so hate- her hypocritical superiority and her self-importance...Solange’s final speech is, for the first time, honest and calm” (Gascoigne, 1970 p 191). Henning (1980) argued that "when Madame returns, the cycle is apparently completed after all. But this, too, remains merely an image. The employer herself is not the genuine Bourgeois Mistress she first seems, nor really a Faithful-Woman-Suffering-for-the-Man-She-Loves. She, too, is only playing a role. Her actions even appear derisory copies of the maids' opening ritual gestures. She is herself but another surrogate monarch...Claire does assume the behavior of their mistress, but during the maids' private ceremony, it is Solange, not Madame, who plays the servant's part. The ritual reversal of roles is thus only partially achieved, and the servants can only degrade themselves" (pp 80-81). "The maids, wearing alternately their uniforms and their mistress' clothes, have a dual identity in several respects: humiliated drudges and triumphant vindicators, prisoners and imaginary voyagers, creators of beauty and slaves to the kitchen range, to which they add still another form of duality, that of the child and grown-up...When Claire puts on her mistress' dress, it has to be pinned up considerably for she is far too little to fit in adult attire. That Claire and Solange may not be fullgrown is further suggested by the fact that they sleep in folding cots. Although they dedicate their lives to revenge, they recite prayers in their room in the manner of pious children. They adorn their attic with fetiches, including Madame's bouquet, a behavior which is indicative of the child's refusal to part with any possession" (Hubert, 1969 pp 204-205). “The maids emulate madame because they desperately desire to be integrated into the aristocratic echelon of society...Claire and Solange have no identity of their own except in relationship to madame; therefore, they want to possess the only person who defines their existence...Madame is beautiful, kind, wealthy, and a magnet for men; the maids are ugly, vicious, indigent, and have no male acquaintanceships. Frustrated by their inability to alter their social or economic status, Claire and Solange envy and thus despise madame whose patronizing attitude toward her servants only exacerbates their desire for vengeance. The maids resent being subservient, feel unable to speak honestly to their ‘patronne’ and are increasingly sexually repressed around madame, whose essence is defined by her sexual prowess. Claire and Solange engage in a ritualistic rite designed to destroy the spirit of ‘madameness’ so that the outcasts...can transcend their inferior statuses in defiance of the established ruling class” (Plunka, 1992 pp 176-177). "Madame is, of course, a kept woman and as such bears a curious relationship to the maids themselves. She is actually a member of another sub-world, a higher sub-world than that of the maids, to be sure, but a sub-world nonetheless. And so she too, to a certain extent, lives by fantasy and imagination. We see this at once in the way she dramatizes the arrest of Monsieur. She is not really herself, but alienated, like the maids, in her being. And we see further that the role she plays in her relationship with Monsieur is actually the prototype for the role of the two maids. She recounts now the story of his arrest, the anonymous letters and above all the heroic role which she plays in the whole affair. Solange tries to reassure her. She says that Monsieur is innocent and will be acquitted. 'He is, he is,' answers Madame. And yet a false note creeps in. We gather that Madame rather enjoys her role of martyr and saint. She will be faithful to Monsieur whatever happens. She will follow him from prison to prison. She will give up her elegant life, her beautiful dresses made to order by Chanel, her furs. She has a moment even of false sympathy for her two servants. They will all retire to the country together. They will be faithful to her and she will take care of them" (Pucciani, 1963 p 53). “This extraordinary play, with its perfect one-act structure, its overwhelming dramatic tension, and its density of thought and symbolism, is rightly considered one of the masterpieces of the contemporary theater. It is a play about masks and doubles, about the evanescence of identity” (Coe, 1986b pp 682-683).

“The blacks” “is an ironic howl at and mockery of every thing the paleface thinks, says and, in furtive guilt and repressed aversion, fails to say against the dark-skinned peoples...It is all done with a grin which has little humor, though it will provoke a frightened laugh” (Clurman, 1966 pp 74-75). “Rejecting the ‘white’ value of universal love, the participants in the rite must struggle to discover absolute hatred. At its centre is the re-enactment of the murder of a white woman by Village. The catafalque placed centre-stage supposedly contains her corpse, and there is lengthy discussion about whether Village was attracted to her or not. This is important to Archibald, in charge of the rite, since he has to determine whether the crime was committed out of pure hatred: ‘His crime saves him.’” (Bradby and Finburgh, 2012 p 75). “The principal question...is whether Village committed the murder from the right motivation and in the right spirit. Was his deed executed in a way that would do full justice to the very soul of blackness?...Accordingly it becomes necessary for Village to re-enact the murder...Archibald reminds them of the desired goal: ‘we must deserve their reprobation and get them to deliver the judgment that will condemn us’...They must live up to the concept of blackness as defined by the whites. But [afterwards] the blacks have moved toward...the determiners of their own actions...The judge...aghast that no murder has been committed, sees the evaporation of his role...The possessed...must stop short of murder...for [that] would deprive [them] of possession” and so the roles become reversed (Jacobsen and Mueller, 1976 pp 158-162). “In relation to each other, Village and Virtue are powerless; both are Black and their Blackness is negation, is nothing but a function of White. Its only chance of self-realization is to reverse the roles of Figure and Reflection. Only by destroying-conquering, dominating or absorbing-White, by asserting its own values against those of the conquerors, will Black become the Figure, and White be re- duced to the part of Image-in-the-Mirror” (Coe, 1968 p 292). There is a tight relation between stage events and the uprising behind the scenes. “The play performed for the audience is a deception that masks the underlying motive of the blacks onstage: a ritualistic self-immolating and subsequent exorcism of white values, producing a rite of passage to a new identity...The whites in the audience are at ease to see blacks imitating white culture...The blacks are associated with the white 19th century colonialist view of Africa as a savage primitive world...The court, played by blacks in white masks, represents white society, or at least a stereotyped black view of what white society represents...Dispossessing themselves from white authority and power, the blacks establish their own identities and begin to make their own judgments which are manifested by the offstage trial of a black traitor...Diouf, as Marie, gives birth to five dolls representing the white court...[signifying] the murder of the white race” (Plunka, 1992 pp 226-233). “The ritual is designed to disintegrate the white image, the uprising to disintegrate the whites” (Brustein, 1964 p 408). "All the whites in Genet's play are uniformed and stand for more than themselves. They are, in fact, symbols of authority. In colonial Africa native secret societies and social clubs often gave their officers the costumes and titles of queen, governor, judge, and missionary, thus both emulating the whites and challenging their monopoly of the symbols of authority" (Graham-White, 1970 pp 210-211). “The court is made up of blacks wearing white masks. These masked beings secretly long to reverse the order of things and become the oppressors, the voice of authority. Yet they know very well that they belong to the black unprivileged race...The members of the white court want to assume their obligations, which indicates a certain faith in the future; however, they do not want to assume their functions as whites but as blacks” (Knapp, 1968 p 137). “The court in this play is ineffective. It is the blacks who must try one of their own. Part of the ineffectiveness of the white court is the fact that they cannot keep up a normal conversation. Their speech is marked by random outbursts that lead the trial nowhere. One reading of this can be that a white court cannot understand and make sense of a black crime...Another reading can be that...justice is impossible to the blacks” (Bennett, 2011 p 82). "The destruction of the whites as they appear is seen as the only way to better their condition. The blacks fight the whites in their purpose to obtain political independence and be able to enjoy emotions other than hatred" (Thody, 1979 p 199). "'The blacks' begin by dancing a minuet to a Mozart melody around a catafalque which occupies center stage. Even though the element of parody is apparent in their movements, the minuet signifies the enslavement of the blacks to white culture. That enslavement is both the starting point and the ending of the play" (Oxenhandler, 1975, p 422). "The actors enter in two groups...but the final stage image is one of solidarity: 'all the blacks- including those who had been the court, now without their masks- stand about a coffin draped in white...The traditional values of white society are scorned, belittled, and reduced to playing 'a tune by Charles Gounod', knitting 'balaclavas for chimney-sweeps', singing 'at the harmonium' and praying on Sundays...The actors are working themselves up into a state of excitement in anticipation of the 'murder' of Diouf (disguised as a white victim), when Village halts the action. Up until this point, Village has painstakingly tried to explain his actions to the audience in repeated asides, but now the whole ceremony is going to move beyond the comprehension of the audience as narrative gives way to magic...Throughout Diouf's recitals, the court integrates itself with the players in the ceremony. They applaud and laugh at the mimed gestures as though they were real. Meanwhile, the white spectator marooned on stage, his hands tied, so to speak, by holding the knitting, can do nothing but look on...The action of the play does not aim to resolve the conflicts of the initial situation; rather, it tends to exacerbate them" (Webb, 1969 pp 455-458). "The Missionary...proudly states, to the tacit agreement of white believers and the bemused rejection of the black ones, that God is white, a belief used over the centuries to keep God-fearing blacks from seeking to reach too far up the ladder of equality. 'For two thousand years God has been white. He eats on a white tablecloth. He wipes his white mouth with a white napkin. He picks at white meat with a white fork.' The blacks realize that their eventual mental liberation cannot be achieved until they are able to reject and revise color symbols such as used by the whites. Thus, Felicite, toward the end of the play, states that 'everything changes. Whatever is gentle and kind and good and tender will be black. Milk will be black, sugar, rice, the sky, doves, hope, will be black'...The blacks in the play derive utmost pleasure from emphasizing precisely those ideas or views that society has held against them...From the very beginning, blacks proceed with a black-is-beautiful ritual, never missing an opportunity to emphasize their blackness and being chided if they appear not to do so. Archibald, who keeps the action moving along...advises Neige: 'You wanted to be more attractive- there's some blacking left'" (Warner, 2014 pp 201-203). "The whole play is a hymn of hatred: the loathing of blacks for whites deliberately played upon and gloried in...the catafalque remains throughout the play visually at the centre of the stage. It is thus precisely one of the deepest of all racist fears that Genet plays on, namely interracial sexual jealousy" (Martin, 1975 pp 519-522). “However much his white audience may disapprove of what the negroes are doing, they are not seeking evil for its own sake, but for political aims that can be rationally formulated: independence, freedom, self-respect” (Thody, 1968 p 200).

Antonin Artaud prefigured Genet’s theatre in its myth-creating goals, the use of language as incantation, communicating emotions rather than exchanging ideas, and the use of visual and auditory aids in the form of “music, dance, plastic art, pantomime, mimicry, gesticulation, intonation, architecture, scenery, and lighting” (Artaud, 1938). “Genet pulls his myths from the depths of a totally liberated unconscious, where morality, inhibition, refinement, and conscience hold no sway; at the basis of his work is that dark sexual freedom which Artaud held to be the root of all great myths" (Brustein, 1964 p ). "All Genet’s plays present us with anti-societies. The worlds of prison, brothel, blacks or rebels are all defined by opposition to traditional, habitual, right-thinking society. The people inhabiting these worlds are all aware that their existence and, more profoundly, their very consciousness is conditioned by the contempt of others. But Genet’s plays do not therefore, like some absurdist dramas, dissolve all social distinctions in a vision of nightmarish horror. Instead, they investigate with precision the levels of interdependence that link the oppressor to the oppressed and they present ceremonies of metamorphosis in which the oppressed, by accepting and exaggerating their condition, hope to turn their shame into pride, to change the rules of the game so as to turn the tables on their oppressors“ (Bradby, 1991 p 179).

"The maids"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1940s. Place: France.

Text at https://web.mit.edu/jscheib/Public/phf/themaids.pdf https://pdfcoffee.com/genet-jean-the-maids-amp-deathwatch-grove-1954pdf-2-pdf-free.html

Claire commands her servant, Solange, to dress her up in all her finery. Her constant recriminations incite Solange to fury. She strikes Claire and threatens worse until the alarm-clock rings, at which point Claire cries out: "Let's hurry. Madam will come back." Claire is a servant as well and they have only been play-acting. Claire blames her sister for always being late, so that they never reach the moment of their mistress' murder. Despite frustrations inherent in their servile state, Claire is nevertheless of the opinion that at heart their mistress loves them. "Yes," Solange comments sarcastically, "like the pink enamel of her latrine." To avenge themselves of their lot outside of play-acting, Claire has written an anonymous letter to the police, accusing her mistress' lover of robbery and leading to his arrest. Solange intends to go further, revealing that she was once tempted to kill their mistress as she slept, but her courage failed her when she moved. "She will corrupt us with her softness," she warns. To their consternation, Claire learns from a telephone call that the man was set free on bail. Claire blames her sister all the more for failing to kill her. Now they well may be denounced as false accusers and imprisoned. "I have enough of being the spider, the stem of the umbrella, the sordid and godless nun with no family," Claire says despondently. They whip up further accusations against their mistress but to no practical avail. "Yet we can't kill her for so little," Solange admits. She suddenly changes her mind again, and suggests dissolving barbiturates in their mistress' lime-blossom tea. Their mistress enters, distressed about her lover's state, ready to follow him to a far-away prison. "I will have newer and more beautiful dresses," she decides. She gives Claire her silk dress and Solange her fur-coat. Then she notices the telephone off the hook. Solange blurts out that her lover called. She is led on to reveal that her mistress is to meet him at a restaurant. The mistress wants to join him at once and leaves before drinking the tea meant to poison her. "All the plots were useless. We are damned," Claire concludes. Solange suggests that they should escape, but Claire finds the suggestion impractical, both being poor with nowhere to go. They uselessly curse their servile state. In despair, they resume play-acting, Solange this time in the mistress' role asking for her tea. But then Claire resumes the mistress' role again to swallow the poisoned tea while Solange's hands cross themselves as if already handcuffed.

"The blacks"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1950s. Place: White-colonized Africa.

Text at ?

A group of black people present the murder of a white woman on a stage in front of a court composed of other black people thinly disguised as whites, including a queen, a governor, a judge, a missionary, and a servant. Archibald Absalon Wellington is the master of ceremonies, guiding the spirit of the presentation towards greater hatred of white colonization. Before a hearse, Archibald asks Village what happened that morning, who answers he strangled a white woman named Mary with his own hands. On hearing of this event, the queen grieves. "Be confident, your majesty, God is white," the missionary consoles her. When some of the blacks are distracted from contributing to any worthwhile cause, Archibald reminds them that they must merit the court's reprobation. In their stage presentation, Mary's role is played by Diouf, a vicar, Mary's mother's role by Felicity, a whore, and a man named Bobo her neighbor. While Mary speaks to her eventual rapist and murderer, the mother constantly cries out for her "pralines and aspirin" and reminds her it is time for prayers. The neighbor copmes over to remind Mary that her eyes may be ruined if she continues to work in the dark. During the course of the evening, Mary plays the piano, an art approved of by the queen: "Even in adversity, in a debacle, our melodies sing out," she declares enthusiastically. Unexpectedly, Mary is about to give birth. The neighbor arrives as the midwife and takes out from beneath her smock dolls representing the five members of the court. She is then murdered and the court convenes for the condemnation of the murderer. The missionary considers that the victim should be beatified, but the queen is uncertain whether that idea is wise. "After all, she was sullied, defending herself to the last, I hope, but she may remind us of her shame," the queen considers. During the court proceedings, the black people rebel and the five members of the court must escape their fury. To ease their fatigue on their way along roads and fields, the missionary approves of the use of alcoholic drinks. However, they get drunk. "Dances occur only at night, none of which do not intend our deaths. Stop. It is a frightening country. Each brushwood conceals a missionary's tomb," the missionary warns them. The judge succeeds in re-organizing the court in session, whereby the members of the black population begin to tremble, but one of their leaders, Felicity, arises to challenge the queen. Another of the black leaders, Ville de Saint-Nazaire, reveals that a traitor in their midst has been executed, but that a new leader of the rebellion is found. The court-members are surrounded, yet the queen admonishes them to courage amid adversity. "Show those barbarians that we are great by our attention to discipline and, to white people looking on, that we are worthy of their tears," she declares. Despite this encouragement, one by one the members of the court are executed.

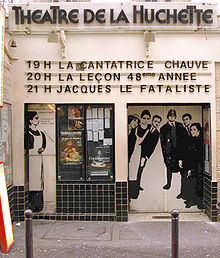

Eugène Ionesco

[edit | edit source]

The Theatre of the Absurd originated in France in the 1940s, the first of whose main proponents is Romanian-born Eugène Ionesco (1909-1994) with "La cantatrice chauve" (The bald soprano, more precisely the bald primadonna, 1948) and "Rhinocéros" (Rhinoceros, 1959). "Both Ionesco and Beckett are concerned with communicating to their audiences their sense of the absurdity of the human condition" (Esslin, 1960 p 671). "If a good play [in the Realist style] must have a cleverly constructed story...[Absurdist plays] have no story or plot to speak of; if a good play is judged by subtlety of characterization and motivation, these are often without recognizable characters and present the audience with almost mechanical puppets; if a good play has to have a fully explained theme, which is neatly exposed and finally solved, these often have neither a beginning nor an end; if a good play is to hold the mirror up to nature and portray the manners and mannerisms of the age in finely observed sketches, these seem often to be reflections of dreams and nightmares; if a good play relies on witty repartee and pointed dialogue, these often consist of incoherent babblings" (Esslin, 1974 pp 3-4) "The convention of the absurd springs from a feeling of deep disillusionment, the draining away of the sense of meaning and purpose in life, which has been characteristic of countries like France and England after the Second World War. In the United States, there has been no corresponding loss of meaning and purpose” (Esslin, 1974 p 266). Unlike Camus’ essay, “The myth of Sisyphus”, and Sartre’s novel, "Nausea", both of which treating rationally of irrationality, Ionesco and other members of the Theater of the Absurd treated irrationality in an irrational manner. “An irrationalist theater is not merely a theater that attacks the idols of rationalism, indefinite progress towards happiness through science...it is, above all, a theater which is meant to be a genuine expression of the irrational” (Doubrovsky, 1973 p 12). In the 1950s to the 70s, absurdist plays or plays with absurdist elements dominated to the extent that, in the view of Fuegi (1986), “it is only the absurd drama that is not absurd” (p 204).

In "The bald prima donna", "the picture of the human condition...is cruel and absurd (in the sense of devoid of meaning). In a world that has no purpose and ultimate reality the polite exchanges of middle-class society become the mechanical, senseless antics of brainless puppets. Individuality and character, which are related to a conception of the ultimate validity of every human soul, have lost their relevance...The audience knows no more about the mcaning of the mechanically senseless dialogue than do the characters themselves. What is involved is a savage satire (which is by no means the same as irony) on the dissolution and fossilization of the language of polite conversation and on the interchangeability of characters that have lost all individuality, even that of sex. Such characters lead a meaningless, absurd existence.... My contention is that the source of...laughter is not to be found in any irony but in the release within the audience of their own repressed feelings of frustration. By seeing the people on the stage mechanically performing the empty politeness-ritual of daily intercourse, by seeing them reduced to mechanical puppets acting in a complete void, the audience while recognizing itself in this picture can also feel superior to the characters on the stage in being able to apprehend their absurdity- and this produces the wild, liberating release of laughter- laughter based on deep inner anxiety" (Esslin, 1960 pp 671-672). The play “is almost in its entirety an exaggerated depiction of the hollowness of bourgeois life through the use of caricature...What is frightening...is how closely it resembles the banal conversations that go on in middle-class homes night after night...The characters hide their boredom and their dislike for one another behind the clichés of polite speech and the routines of conventional behavior. So mechanical have their lives become that they are incapable of learning anything” (Abbott, 1989 p 159). “The dialogue is mainly in the form of self-contained statements that attempt little interlay...When the dialogue is initiated...conversation is little more than sense destruction...[When] the Martins are introduced...the dialogue...grows out of their mutual wonder over the coincidence of their parallel existence. This process is the reverse of the incongruity that fails to surprise; here it is the expected that evokes stereotyped amazement” (Grossvogel, 1962 pp 53-54). "The bald primadonna" presents "characters...already devoid of humanity...who do not possess even a memory of propitious times, who are the same at the falling of the curtain as they were at the beginning, and who seem unconcerned with any possible release from their imprisoned circumstances- indeed...are unaware of any imprisonment...lack any tragic sense of their condition...The incredible elicits little surprise, [as when the fireman rings the doorbell], the ordinary is greeted with incredulity” [as when Mrs Martin describes a man tying his shoelace in the street]" (Jacobsen and Mueller, 1976 pp 46-54). The conversations between the Smiths and Martins derive from instruction manuals to master a new language (Hayman, 1976 p 17). “The dislocation of everyday language in the play is progressive, passing through several phases. At the beginning of the play, the language is remarkable primarily for its sheer inanity...The second stage in Ionesco's assault on language encompasses most of the rest of the play; it begins when Mr. Smith starts to speak and continues until the departure of the fire chief (scene 10). As soon as the monologue becomes dialogue, it is apparent that the logic governing the world of this play has nothing to do with that of the spectator's world. In this part of the play, the forms of polite conversation are left largely intact, but their content is skewed and zany” (Lane, 1994 pp 31-32). “The Smiths and the Martins...are devoid of identity. The characters mimic each other for lack of imagination, parroting contemporary clichés and boilerplate remarks because they are so eager to please they have lost any semblance of self outside the herd” (Krasner, 2012 p 308). “The Martins’ problem is that, even though they have been introduced to us as man and wife, they don’t know each other...we see a typical couple, married for some years, who do not know each other” (Wellwarth, 1971 p 62). "No sooner have the chimes struck seventeen times than Mrs Smith announces that it is nine o'clock. A joke? Of course it is a joke. But it also reveals that the specific time of day is meaningless, because from hour to hour and day to day, their lives are essentially the same. It is also noteworthy that the couple is named Smith: a perfectly conventional, nondescript, middle-class name for conventional, nondescript, middle-class people...The uniformity, as well as the lack of vital life in the lives of the members of the bourgeoisie, is revealed when the Smiths discuss Bobby Watson...There is no difference in the pattern of existence between one bourgeois and another...Ionesco frequently employs a grotesque reversal of the usual. He accomplishes this by taking a familiar situation, injecting into that situation a single element which renders it completely improbable, and then writing the scene as though the improbable element were not there. Such a scene occurs when Mr and Mrs Martin enter...and Ionesco presents not only a brilliant satire on cocktail party conversation, but- and more to the point- on the bourgeois preoccupation with inconsequentials. At first, each of the characters gropes for something profound with which to impress the others. The result is a plethora of banalities...Mr Smith goes to the door and returns with the fire chief...[The explanation of the doorbell matter] satisfies all concerned, for it is the classic bourgeois manner of settling controversies: choosing the middle path between two extremes...Enter the Maid, who turns out to be the fire chief's sweetheart. Here, too, passion is extinct, for, as the fire chief declares, 'it was she who extinguished my first fires'...When the fire chief leaves, Ionesco presents another illustration of the dull routine of these people's lives. The party conversation becomes a series of clichés: 'to each his own,' 'an Englishman's home is truly his castle,' 'charity begins at home'- [which] follow each other with no logical continuity"(Dukore, 1961 pp 176-177). Lane (1996) enumerated the disruptions of logical discourse include pseudo-explanations (the patient died because the operation failed), false analogies (a conscientious doctor must die with his patient like the captain of a sinking ship), contradictions (the Smiths have had dinner until the maid enters), specious reasoning (when the doorbell rings, it is because no one is there), surprise at the obvious (why newspapers never print the age of newborns), unreliability of proper names (the Watsons), aphasia (a woman is asphyxiated because she thought the gas was a comb), word-action contradiction (the fire chief says he will take off his hat but not sit whereas he does the reverse). The characters lack any discernable motivations, rationality, or internal life, rather they are like puppets...Undifferentiated from each other and indistinguishable from their surroundings, they are traversed by language which uses them rather than the other way around” (pp 32-39).