History of Western Theatre: 17th Century to Now/French Realist

"The rise of dramatic naturalism was favored in France by the example of the novelists. Balzac, with his all-embracing comédie humaine; Flaubert, with his finely wrought fictions, minutely faithful in observation and expression; the de Goncourt brothers, with their meticulous striving to represent the pathological; Daudet, with his polished and ironical mingling of the romantic and the realistic de Maupassant, the pupil of Flaubert, with his tales beautiful in workmanship yet fearless in their reflection of the actual and finally Zola- big, coarse, brutal, gorging himself on human documents, and pouring out floods of turgid epic eloquence: all these prepared the way for naturalism on the stage...Vice and crime are the themes of the naturalists, morbid longings, distraught minds, sordid evils of the social system. Life, they argue, must be faced in its grimmest and most horrible aspects; only so can it ever be improved" (Chandler, 1920 pp 51-52).

Zola is associated with naturalism, which "signifies not only a strict, often extreme, mode of realism, but a rather narrow dogma introduced into dramatic theory by Emile Zola in 1873, in his...preface to ‘Thérèse Raquin’...Zola’s program for the theatre called upon writers to concentrate on data arrived at objectively...The strictly naturalistic view was mechanistic, physiological, and deterministic. The individual was to be exhibited as the product, puppet, and victim of the inexorable forces of heredity, instinct, and environment, for man was to be regarded as a wholly natural object subject to natural processes” (Gassner, 1956 p 67). In the view of Chandler (1920), Zola "thought himself a naturalist; as a matter of fact he idealized the low, the brutal, the sensational. His style was ponderous and blunt rather than graceful and keen; he professed to be scientific but was often guilty of straining for effect" (p 58).

“The naturalists aimed to differentiate ordinary citizens. Aphorisms were frowned upon. Brilliancy gave way to the commonplace. Hugo had democratized the noble vocabulary and style of classical drama. The naturalists believed that the dialogue of drama was still too rhetorical and prudish. When Zola employed a few words of slang in his Bouton de Rose, the audience was scandalized. The playwrights were undaunted. As they depicted the seamy side of life, so they used defiantly the crude or obscene vocabulary of the milieu, each vying with the other to see how far he could go. Any kind of language, didactic, poetical, brilliant or crude is inartistic if it causes the spectator to think of the author or the actor instead of the character. Dumas intrudes in his didacticism, Hugo in his poetry, Wilde and Shaw in their brilliancy” (Stuart, 1960 p 551).

French realism of the late 19th century was liable to offend many British and American critics, in the latter case for example Ingersoll (1900), who wrote: "the modern French drama, so far as I am acquainted with it, is a disease. It deals with the abnormal. It is fashioned after Balzac. It exhibits moral tumors, mental cancers and all kinds of abnormal fungi,- excrescences. Everything is stood on its head; virtue lives in the brothel; the good are the really bad and the worst are, after all, the best. It portrays the exceptional and mistakes the scum-covered bayou for the great river. The French dramatists seem to think that the ceremony of marriage sows the seed of vice" (pp 528-529).

Honoré de Balzac

[edit | edit source]

In the late 19th century, French theatre is ably represented by Honoré de Balzac (1799-1850) with "La marâtre" (The stepmother, 1848) and "Mercadet, le faiseur" (Mercadet, the speculator, 1851), worthy to be placed next to his novels. More minor works include "The school of home maintenance" (1839), "Vautrin" (1840), and "Pamela Giraud" (1843). In the latter play, Pamela compromises her reputation by perjuring herself in court that she was with her lover, Jules, without her parents' consent to save him from being falsely accused of a plot to overthrow the government.

According to Stuart (1960), “The stepmother” “is a clumsy, yet powerful piece of work. The plot is somewhat romantic with its stolen letters, deaths by poison, and the appearance of Pauline after she seems to have died. The dialogue is inept, labored and full of asides which explain badly the real sentiments and purpose of the characters...One only has to compare La Marâtre with Turgeniev’s A Month in the Country (1855), founded on a similar situation, to realize what exaggerated theatrical people Balzac created” (pp 542-543). One may counter that this opinion depends too much on realism as the ultimate criterion of a good play. The critic is biased against romanticism, especially Balzac's mixed genre of romanticism and realism.

"Mercadet, the Speculator is inspired by François Rabelais' Tiers Livre [Third Book] (1546). Mercedes defends the use of being in debt to his wife in a manner analogous to Panurge's defense to Pantagruel (Fess, 1925 pp 55-56). "Mercadet...is a second Figaro, with a strong likeness to Balzac himself. He is continually on the stage, and keeps the audience uninterruptedly amused by his wit, good-humour, hearty bursts of laughter, and ceaseless expedients for baffling his creditors. The action of the play is simple and natural, and the dialogue scintillates with clever words, gaiety, and amusing sallies. The play had been conceived and even written in 1839 or 1840, and never did Balzac’s imperishable youth shine out more brilliantly than in its execution. It is curious to notice that his innate sense of power as a dramatist, which never deserted him, even when he seemed to have found his line in quite a different direction, was in the end amply justified" (Sandars, 1904 p 328). "This play is truly living. Occasionally the veil of formality and shallowness is rent apart, and one gains a glimpse of the dark stream of time carrying all with it, and one understands a little of the working of men's minds" (England, 1934 p 190).

"The stepmother"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1829. Place: Louviers, France.

Text at http://www.archive.org/details/stepmothermercad00balziala https://archive.org/details/dramaticworksofh02balziala http://www.readbookonline.net/title/21005/

The count of Grandchamp, a retired general in Napoleon's army, and his wife, Gertrude, are thinking of the future of Pauline, his daughter of a previous marriage. In her stepmother's view, Pauline should marry a wealthy landowner, Godard. Both are surprised when Pauline rejects him, because she secretly favors Ferdinand, her father's clerk and an old love of Gertrude's. Although Ferdinand desires to marry her, he cannot, being the son of a general who abandoned Napoleon, and therefore one whom Grandchamp will never accept as son-in-law. Godard desires to discover whether Pauline loves Ferdinand. He enlists the help of Napoleon, the general's twelve-year old son, who shouts that Ferdinand has fallen downstairs, whereby Pauline swoons, confirming Godard's suspicion. Godard reveals this information to Gertrude, who betrays to him her own feelings for Ferdinand, with whom she wishes to renew her amorous relation begun before her present marriage. To scrutinize further into Pauline's sentiments, Gertrude lies to her by saying Ferdinand is already married, but she appears unmoved at this, as Ferdinand is when she lies a second time by saying that the general will command Pauline to marry Godard. "You hate her, and in this word 'hate' there is more love for me than in anything you have said to me these two years," Pauline admits to her lover. When Gertrude sees the two together, she threatens to reveal this to her father, but Pauline feels safe, knowing she can threaten back with the love-letters Gertrude wrote to Ferdinand which he still possesses. When Gertrude begs Ferdinand to remain hers, he refuses. As a result, she discloses Pauline's love of Ferdinand to her husband. Pauline denies it even before her lover's face. Alone with Gertrude, Pauline reveals she has entered Ferdinand's room and obtained her love-letters. As they drink tea with the general and Godard, the latter ready to reveal Ferdinand's identity, Vernon, the family doctor, notices Gertrude pour something into Pauline's cup. Unnoticed, he takes it away from her and discovers the taste of laudanum, because of which Pauline dozes off, carried to her room with a servant's help by Gertrude, who finds the letters and burns them. Vernon confronts her with the laudanum, but she utters vaguely that four lives are now at stake concerning this matter. On awaking, Pauline suggests to Ferdinand that they should elope this very night, but they are intercepted by Gertrude. Cornered, Pauline steals poison from Gertrude's room, discloses Ferdinand's identity to Vernon, and pretends to accept Godard as her husband. Gertrude enters with tea for her, into which Pauline drops the poison and drinks it. As she lays dying, the examining magistrate wonders why Vernon, knowing about the laudanum, failed to prevent Gertrude from poisoning her stepdaughter. Gertrude is astonished at being accused of poisoning, guesses the truth, but is unable to prove her innocence until Pauline reveals the choice of suicide was hers. In despair of losing her, Ferdinand also swallows the poison.

"Mercadet, the speculator"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1840s. Place: Paris, France.

Text at http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/14246 http://www.readbookonline.net/title/22025/ https://archive.org/details/dramaticworksofh02balziala

Heavy with debts, Mercadet has spread rumors that his daughter, Julie, is about to marry De la Brive, a rich man. This fortunate piece of news convinces one of Mercadet's creditors, Boulard, to write for him a letter in support of a delay to his other creditors, as well as 1,000 crowns, in exchange for information relating to the 350 shares in Basse-Indre stock Boulard should sell. The devious Mercadet reveals to his wife the purpose of this maneuver. "It is in the interest of my friend, Verdelin, to cause a panic in Basse-Indre stock," he confesses. "This stock has been for a long time very risky and has suddenly become of first-class value, through the discovery of certain beds of mineral, known only to those on the inside." Next, he obtains 6,000 francs from another creditor, Violette, as an investment for a new kind of pavement. To entertain his future son-in-law, he needs from Verdelin 1,000 crowns and his dinner service and for him to come and dine at his house with his wife. Violette at first resists giving him the money but at last yields to the pleadings of Julie. However, Mercadet's plans are in danger to be upset by Julie's reciprocated love of Adolphe, a mere book-keeper. As previously done with his creditors, Mercadet assures Adolphe he is a ruined man. "All payments are made in alphabetic order," he says as he reveals papers of his long list of creditors. "I have not yet touched the letter A." This frightens Adolphe, but he nevertheless remains loyal to Julie. "I will render her happy by other means than my tenderness," he declares. "She shall feel grateful for all my efforts, she shall love me for my vigils and for my toils." Yet he cannot have her. "A brilliant marriage for my daughter is the only means by which I would be enabled to discharge the enormous sums I owe," Mercadet tells him, pleading not to force her to a life of poverty. Heartbroken, Adolphe accepts this viewpoint. Though De La Grive also owes a great deal of money, he has lands to be exploited and so Mercadet accepts him as a son-in-law, each thinking the other richer than he is. However, Mercadet discovers in time from Pierquin, another of his creditors, about the extent of De La Grive's debts and the poor prospect of his lands and so dismisses him. As a result, an angry Verdelin threatens him. "Pierquin tells me that your creditors are exasperated and are to meet tonight at Goulard's house to conclude measures for united action against you tomorrow," he reveals. Adolphe returns with money from a legacy of 30,000 francs, so that Mercadet, moved by this generosity, consents at last to give him his daughter's hand in marriage. Next, to calm down his creditors, he proposes to De La Grive to pretend he is Godeau, a man who once robbed him, returned with the stolen money. Although De La Grive agrees at first, Mercadet's wife makes him realize the danger of that operation and so he desists. Thinking Godeau's arrival imminent, Mercadet brazens it out with his creditors, asking Adolphe to supply his 30,000 francs as if they came from Godeau. The creditors go to him and, to Mercadet's astonishment, receive the full amount owed them, for the real Godeau has arrived.

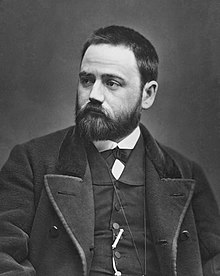

Émile Zola

[edit | edit source]

Émile Zola (1840-1902) adapted “Thérèse Raquin” (1873) from the novel of the same name (1867). Zola also wrote "Renée" (1887), based on another novel, "The kill" (1872). In the latter play of more minor interest than “Thérèse Raquin”, Renée is raped by the father of one of her friends. To avoid being ostracized, she agrees to marry Aristide Saccard provided they live apart. Thanks to the head-start he has with her money, Aristide accumulates a great deal of wealth with financial speculations during the course of ten years while Renée becomes infatuated with Aristide's son from a previous marriage, Max. Unknown to Aristide, they engage in sexual relations. Aristide comes to love Renée, but she refuses her husband as a bed-partner. To bind her more closely to him and to pay off her debts, Aristide proposes to sell some of her land-property without informing her he is the buyer, but Max discovers the trick and reveals it to her. She proposes to leave her husband for Max, but the latter refuses, preferring instead to marry Ellen, daughter of the Swedish ambassador, a choice Aristide approves of so that he can speculate on his silver mine. Disgusted with everything, Renée shoots herself to death with Aristide's pistol.

“In dramatizing his novel, Thérèse Raquin, Zola tried to make the play a study of human life. The action did not consist of a manufactured plot, but was to be found in the inner struggle of the characters. There was to be no logic of facts, but a logic of sensations and sentiments. He said in the preface: ‘The denouement was the mathematical result of the proposed problem. I followed the novel step by step; I laid the play in the same room, dark and damp, in order not to lose relief or the sense of impending doom I chose supernumerary fools, who were unnecessary from the point of view of strict technique in order to place side by side with the fearful agony of my protagonists the drab life of every day; I tried constantly to make my setting in perfect accord with the occupations of my characters, in order that they might not play but live. I counted, I confess, and with good reason, on the intrinsic power of the drama to make up in the minds of the audience for the absence of intrigue and the usual details” (Stuart, 1960 p 545).

“Thérèse Raquin" "was dramatised by Zola from his novel, a great work; but the play itself is not in itself great. The characters are mean, petty, and sordid; their language is that of the bourgeois family to which they belong; their lives are commonplace, until lust exercises power over Laurent and Thérèse, and then the tragedy of the situation asserts itself and is ever present, and culminates in the suicide of the guilty ones. We see the everyday life of a humble Parisian household" (Howard, 1891 p 192).

“Thérèse Raquin" "consists in the working out through character of the necessary consequences of a given action. And that action in itself is not fortuitous but had resulted, in its turn, from the contact of character with character. In a word, Zola succeeded measurably in using a logic 'not of facts but of sensations and sentiments'. The play contains in addition that close-packed portrayal of milieu and character which is characteristic of the best dramatic work of its kind. As in his novels, to be sure, Zola could not wholly escape the lurid. The paralysis of Mme Raquin, her late discovery of her daughter-in-law's guilt, the dreadful revenge of the silenced woman- these are the fruits of Zola's romantic appetite for the monstrous and merely horrible. Yet 'Thérèse Raquin', with its stringent evolution, its unity of place and its strong verisimilitude, bears witness to the power and intelligence if not to the fineness and genius of its author's mind“ (Lewisohn, 1915 pp 37-38).

"Thérèse Raquin" "is a grim and ghastly drama, full of main strength and directness, and having the simplicity of genius...The figure of the paralyzed Madame Raquin, ever present between the two murderers of her son, like a palpable and implacable ghost, gazing at them with eyes of fire, and gloating motionless over their misery, is a projection of unmistakable power" (Matthews, 1881 p 280).

“Thérèse Raquin”

[edit | edit source]

Place: Paris, France. Time 1870s.

Text at ?

After taking care of her sick uncle in her youth, Thérèse married his son, Camille Raquin, but is disenchanted about their marriage life, partly due to his poor health. She has a lover, Camille’s best friend, Laurent. They dream of spending their life together. To cover her tender feelings for him, she pretends to dislike him in social gatherings. All their friends and Thérèse’s mother, Mrs Raquin, are taken in by her subterfuge. To thank his friend for painting his picture, Camille proposes that he and his wife take Laurent along with them for a day trip at Saint-Ouen, where the lovers seize their opportunity by murdering him when Laurent overturns the longboat and saves only Thérèse from drowning. One year later with Thérèse still in pretended mourning, a family friend, Michaud, convinces Mrs Raquin that the best thing for Thérèse would be to marry Laurent. She reluctantly agrees. Laurent and Thérèse are joined in marriage, only their happiness is all too brief, starting on their wedding night, when thoughts of the murdered man creep into their heads. Thérèse cries out in protest when her husband lovingly takes hold of her. In frustrated rage, he takes down his painting of Camille from the wall and blurts out in Mrs Raquin’s hearing as she enters to find out the cause of Thérèse’s cries that the two are guilty of Camille’s murder. As a result, Mrs Raquin has an apoplectic fit and is unable to speak or move. To the horror of the guilty couple, one night while playing dominoes with their friends, Mrs Raquin recuperates to the extent of jotting down a message regarding the guilty couple, but stops short of accusing them of murder. Instead, she wishes to extend their sufferings by deliberately delaying the revelation to others, to have it hang over their heads whenever people visit them. Overwhelmed with feelings of guilt, Laurent and Thérèse blame each other for the deed. To end it all, Laurent prepares his wife’s drink with a deadly dose of prussic acid while she prepares to stab him with a knife, only they discover each other's intention in time. Mrs Raquin rejoices in their sufferings. “I will let remorse jostle you one against the other like frightened beasts,” she declares. In despair, the couple drink the poison and die, too soon in Mrs Raquin’s opinion.

François de Curel

[edit | edit source]

French realism was also represented by François de Curel (1854-1928), most strong with "Les fossiles" (The fossils, 1892). Curel also wrote "The reverse of a saint" (1892) about a woman named Julie who loses her chance to win a man because of her rival, Jeanne, is received in a convent, and, once the man dies, seeks to avenge herself against her. In "The guest" (1893), Thérèse discovers her husband's infidelity, leaves him with her two daughters, and sixteen years later gets invited by him as a guest to take care of them. In "The new idol" (1899), a scientist injects dying patients with a cancer-causing microbe to test a vaccine against the disease. His quest of scientific discovery, society's new idol, is hindered when one of his patients spontaneously recovers from the last stages of consumption. The play shows misleading paranoia on the part of the author in regard to the relation between science and society.

In "The fossils", “the Duke de Chantemelle, who has passed his life in his own estates seducing peasant girls and killing boars, has but one idea in his brain and one single article in his moral and religious creed pride of race. The idea has been transmitted to his son Robert and his daughter Claire, but in an idealised form. Claire breathes into it all the passionate sorrow of a soul that has never met with love and is pining away in solitude; Robert interprets it with the delicate generosity and prophetic insight of a mind open to all the needs of the modern world. To him the nobility is sacrifice: let the old aristocracy resume the career of self-devotion, and it will again become worthy to lead society. Thus to all three natures, although for different reasons, the highest and most imperative duty is to perpetuate the race of Chantemelle” (Filon, 1898 p 119). “Beneath Les Fossiles is the problem of the value of culture, honor and civilization, along with the menace of moral degradation” (Smith, 1929 p 216). "The play burns with the white heat of that unflinching dedication to an ideal of secular greatness and endurance. To be sure, we do not believe in Helène who speaks the unspeakable truth in virginal accents. But that is Curel, whose sense of measure and probability are lost in his passionate absorption. His work is unequal, violent and tortured at its best. But it is not easily forgotten, not lightly put aside. The man seems a changeling in his country of firm, sane and accomplished masters, of brilliant, well-tempered, intellectual achievement. His public recognition must always be partial and hesitant, and I am glad to pay this tribute to the genius- however turbid and however often touched with futility- of François de Curel" (Lewisohn, 1915 pp 62-63).

"If the nobility has lived its day, at least let it leave the impression of grandeur conveyed by those great fossils that make us dream of vanished ages. The strange and moving drama, with its tragic implications, awakens sympathy for these unhappy creatures caught in the mesh of circumstance. The old duke, imperious and decadent, draws down upon himself the punishment of heaven for his sin with Helene. She, who loves Robert, has earlier succumbed to the duke out of fear, and shivers at the thought of her crime. The sister of Robert shares his vision of the future and his conception of the duty of the younger generation to redeem the sins of the older. And Robert, wooing death in the very cradle of his race, but dreaming of a regenerated aristocracy that shall be worthy of its responsibilities, is a memorable figure. The speeches are prolonged, imaginative, poetic. The play is one of atmosphere, the background of the moldering castle and the wild forest harmonizing with the human foreground" (Chandler, 1920 p 193). "Depicting as it does the tragedy of a race, the agonies of a dying pride, the struggle between ancestral feeling and personal love and inclination, 'The fossils' is one of the noblest works of our time" (Clark, 1916 pp 10-11).

"From the Theatre-Libre de Curel learned to prefer the unusual, the brutal, and the sad, but his general ideas, his understanding of abnormal psychology, and his sense of beauty, have led him to transcend the works of his colleagues. He has curiously combined the real with the unreal, his plots and personages being often so novel as to challenge credence, yet his poetic fervor being suflBcient to win for them artistic faith for the moment. His work is marked by vividness of conception, intensity of passion, and the brooding of a speculative mind upon remote contingencies in human action. Primarily concerned with the individual, he centers attention upon two or three characters at most. His heroines, dominated by love, are fierce rather than tender; his men, controlled by other and stronger impulses, appear more sympathetic than the women. Technically, de Curel's dramas are better in exposition than denouement. The motives are too often obscure or unduly complex, and the dialogue is too diffuse or too explosive. On the other hand, de Curel displays skill in the coining of epigrams, in the management of background and atmosphere, and in the presentation of the pathetic. Whether dealing with ideas or states of soul, he fuses the real and the romantic. More than any other writer for the French stage, he reveals the temperament and personality of genius" (Chandler, 1920 pp 198-199).

Curel's enduring theme is: “the efforts of individuals to cope with change” (Branam, 1986 p 448). “With Curel has passed one of the most incontestably worthy of recent French dramatists. There was nothing in for which to apologize: nothing that was futile, insignificant, or merely theatrical...He was thoroughly in touch with the great currents that affect modern thought. It was natural then, and this is his particular glory, that he should turn to serious or elevated subjects. At a time when the theatre seemed in danger of being absorbed by the problems of illicit love, or annexed to the social sciences, and when a trivial, surface realism threatened to render it inexpressibly dreary, Curel returned to the tradition of a spiritual drama, to that of the mental or moral crisis of an unusual soul in the grip of great forces, to the eternal problems of existence: knowledge, faith, hope. And this return was not the futile revolt of a reactionary, reaffirming an outgrown classic formula. It is drama expressed in the most modern terms and developed in the full light of scientific thought” (Smith, 1929 pp 214-215).

"The fossils"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1890s. Place: The Ardennes and Nice, France.

Text at http://www.archive.org/details/fourplaysoffreet00clar

Robert, only son of the duke of Chantemelle, is dying of tuberculosis and wishes to see Helen, an old companion of her sister, Claire, who, unknown to either man, chased her away from their house after finding out she was the lover of both her father and her brother. Robert reveals to his mother that he begot a son of Helen. The duchess is astonished. Unknown to Robert and thinking the baby to be his, the duke has arranged for it to be nursed near their manor. The duchess announces to her husband that Robert has a son and that Helen is the mother. The duke curses Helen, but yet the thought of having an heir entices him. Though she herself is "mud" to his mind, he approves of Robert marrying her and tells him he knows about his son. Robert warns him that the day she is made to feel inferior by his mother and sister he will take her away. With the duke's approval, Robert agrees to marry Helen. The duchess is furious at the misalliance and Claire indignant despite not knowing yet of the baby's existence. Unlike her father and brother, Claire hopes that the family name disappears. Ancestors gave to France entire provinces, now her father cannot get elected even as a mayor in the nearby village. What remains? A family of "revolted mummies". For his part, Robert is convinced of the value of heredity, to him their own comprise an "elite progeny". But to Claire, the present aristocracy is typically a "little marquis who knows only how to hunt and dance". When Robert tells her that the marriage was condoned by their father, she states: "That surpasses in horror all that I feared." The duke brutally commands Helen to marry Robert, but there is one danger: Claire, who knows of her father's amorous relations with Helen. "If she talks, farewell marriage, the family falls," the duke affirms. Hoping to save Robert from an abomination, Claire speaks to Helen. The father threatens Claire should she try to impede the plan, but she resists, better anything, in her view, than "to breathe in an atmosphere of shame". Yet when the duke announces that Robert has a son, Claire finally agrees to his marriage. After their marriage at Nice, Robert soon begins to feel ill. "Always the taste of blood in my mouth!" he exclaims. If he dies, Helen wishes to leave a family who scare her, the duchess and Claire being at best "heroically polite". She wants Robert's written statement that after his death she can leave the manor with her son, because her humble and submissive character may lie submissive in such a family. Claire has other ideas. "I'll explain to him your ideas of the nobility that must remain for the country a nursery of generous hearts," she promises her brother. Helen is outraged. What, to yield her child to them! Robert regretfully yields to Helen's wish. Claire panics. What, to take away the child from them! The duke sides with his daughter. "The child is mine," Robert counters. "Mine," the duke echoes, revealing that Helen was his love before she ever was Robert's. "Now, if you want me to die, I'm ready," the duke asserts to his son. Lurching out, Robert counters with the statement that "one of us must die." With the passing of time, the duchess guesses the truth. After Robert's death, Claire reads his will, which states that his parents give Helen and her son their castle in Normandy. "I promised Robert never to marry and to stay all my life with Helen and her child," Claire reveals. The duchess is sorry to lose Claire. To Helen, the duke can only say: "farewell forever."

Émile Augier

[edit | edit source]

Émile Augier (1820-1889) distinguished himself as another initiator of theatre realism, a remarkable example being "Lions et renards" (Lions and foxes, 1869).

In "Lions and foxes", "clericalism re-appears again in the person of a M de St Agathe, mentioned already in the 'Fils de Giboyer', and here brought boldly upon the stage: he is one who has sacrificed every thing, even his identity, to the order of which he is an unknown instrument, from sheer lust of power wielded in secret. The struggle between these two, D'Estrigaud and St Agathe, for a fortune which neither of them captures, is exciting. In the end, by a sudden irony, the beaten D'Estrigaud abandons the world, forgives his enemies, and, under the eyes of St Agathe, takes to religion, the last resort of rascals, to paraphrase Dr Johnson" (Matthews, 1881 pp 128-129). According to Fitch (1948), "there is a fundamental weakness in the intrusion-plot...in that the key-character is well aware of what is transpiring around her. Catherine is wealthy and as nearly independent as a young woman in her environment could be, and though she is not completely in control of events, we have difficulty in believing that her happiness is seriously menaced. Various reasons have been given for the failure of this play, perhaps all partly valid, but not the least of them is that the author was false to the necessary conditions of his own system of construction: without more blindness on Catherine's part the plot lacks the necessary tension" (p 276).

Weinberg (1938) described the opinions of early French critics of Augier's plays as being "too low, too discouraging, too wicked. It was real; but such realities are not the proper domain of the artist...Most undesirable of all was his constant preoccupation with the demimonde, his portrayal of social groups existing on the fringe of society. Another offense was in the use of the vulgar, brutal language that might be spoken in such groups...There were, however, surprisingly few accusations of immorality...He attacked vigorously, they said, the vices of the time; he gave sane and striking moral lessons; he contributed to the correction of manners" (pp 196-198).

Augier “demonstrated a perceptive and, at times, a profound grasp of the psychology and customs of his milieu, infusing his plays with a human interest which could result only from a keen and probing observation of bourgeois society...His prose style liberated French dramatic diction from the exaggerations and histrionic abuses practiced by the previous generation’s Romantic writers, reproducing instead the regular speech patterns of the bourgeoisie” (Araujo, 1986 p 133).

Augier ”began as a follower of Hugo, cut adrift, and, in a form which we would call today realistic, began to scourge national foibles now in sarcastic vein, now in the toga of the moralist...It was often said of Augier that he wrote in the spirit of a bourgeois, that he was dry, that he was caustic without being humorous, and he was certainly less flamboyant in style than Hugo, Dumas, and Sardou. But his plays were full of correct observation, and in their frigid, logical survey of his contemporaries they retained an air of reality which prevented them from becoming antiquated” (Grein, 1921 p 97).

"For the most part, Augier's dramas deal with conditions arising from the incomplete fusion of classes. Thanks to his bourgeois sanity, he was quick to perceive family perils, social follies, and the baneful spell exerted by money. Yet his mind had serious limitations. 'Beyond simple sentiments and regulated affections,' declares René Doumie, 'he saw only dreams, dangerous chimeras, and romantic evils. Perturbations, inexplicable and unreasoning heartaches, sufferings of the sensibilities ami sicknesses of soul, nothing of these existed in his eyes.' His characters are never haunted by the mystery of life; they know neither the charm of the invisible world nor the tormenting obsession of the infinite. Nor, as is evidenced by 'Paul Forestier', could he portray love" (Scheifley, 1921 p 137). “Emile Augier tried to show his fellow-citizens the dangers to which they were liable from financial trickery and loss of moral convictions and ideals. He did so in some of the best constructed plays of the nineteenth century, which present many of its most noteworthy literary types: Poirier. Vemouillet, Guerin, and Giboyer, the bohemian journalist, or d’Estrigaud, the new Don Juan. Augier is the one to whom of all the modern dramatists the French are most ready to attribute the good sense of Molière” (Wright, 1925 p 781).

Augier "is noteworthy from more than one point of view. First, he has his place in the development of European drama as a forerunner of Ibsen, Strindberg, Hauptmann and the rest of the moderns. Secondly, he endeavored to produce a most difficult kind of drama, the satiric drama, in which his only successful compeers are Ben Jonson and the younger Ibsen in his verse plays. Finally, as having to all intents and purposes put sociology on the stage for the first time, Augier interest us as exhibiting the special vices of a democratic society and of a democratic government" (Guthrie, 1911 pp 4-5).

"Lions and foxes"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1860s. Place: Paris, France.

Text at ?

After having enjoyed an illicit liaison with him many years ago during a previous marriage and still remaining friendly with him, Octavia, countess of Prévenquière, speaks favorably of Raoul, Baron D'Estrigaud, as a potential husband for Catherine de Birague, an attractive heiress. Alphonse Sainte-Agathe favors instead his pupil, Viscount Adhemar, Catherine's cousin. The baron visits Catherine first and surprises her with a marriage proposal. When she shows no interest, he insolently proposes that she become his mistress, which she vehemently rejects. Adhemar follows soon after with his own marriage proposal. "But I do not wish to marry," Catherine declares. "Neither do I," specifies the viscount. He merely requests her not to refuse him altogether, to let the question hang in the air, long enough for him to amuse himself for a few weeks in Paris before returning in the provinces. Having heard rumors of his wife's indiscretions, Octavia's husband and Catherine's guardian, Edward, has no wish to see the baron in his house. Instead, he enthuses over the merits of his friend, Peter Champlion, who seeks to exploit a goldmine in Wadai, Africa (present-day Chad), if he can attract enough subscriptions, and at the same time liberate a friend from prison in that region. The tale so inflames Edward, Alphonse, and Adhemar that they subscribe immediately to that project, while Catherine provides the greatest amount of money of all. Later, a pleasant chat between Catherine and Peter is interrupted, to her annoyance, by the arrival of the baron, who subcribes with the others. He then pleads on his own behalf regarding whether he deserves pardon from an unnamed lady and asks Peter for his opinion. When Peter discovers the lady in question is Catherine and observes the baron's excessive familiarity toward him, he becomes angry to the extent of challenging him to a duel. Alarmed, Catherine seeks to prevent it by reminding him of his friend imprisoned in Africa, but this does not halt him. Equally alarmed are Octavia and Alphonse, as Peter's boldness in defending Catherine may compromise her towards a man she already shows "all too much a penchant". Alphonse would like Adhemar to fight the baron, but he cannot honorably do so as a result of owing him a gambling debt. Instead, Alphonse strikes a deal with the baron, whereby the former yields compromising letters of his regarding the use of money he once owed to several people in return for reliquishing his pretensions towards Catherine. Moreover, by paying him Adhemar's gambling debt, he frees his pupil for the duel. However, since Adhemar declines to marry her, the payment puts him in a compromising situation towards her. He opts instead to help Peter by quashing false rumors concerning his use of the subscription money, after which they agree to travel together in Africa.

Edmond Gondinet

[edit | edit source]

Edmond Gondinet (1828-1888) continued the realist tradition with a drama amid men's social relations, "Le club" (The club, 1877).

The plot "rests on the traditional situation of marital infidelity, treated in a serio-comic manner, but the interest lies in the keen and witty representation of a men’s club. In the second act we are shown an evening at the club, the different types of habitues, and all that goes on. Only men are present; and yet the plot develops in their conversation, which is delightful satire on club life. The third and fourth acts present a charity bazar, no less cleverly" (Stuart, 1960 pp 553-554).

"The club"

[edit | edit source]Time: 1877. Place: Paris, France.

Text at ?

In Count Fernand de Mauves’ apartment, Maxime Chambois, Viscount Abel de Borne, and Théophile de Pibrac settle the conditions of a duel between Baron de Morannes and Viscount Roger de Savenay. According to Maxime, the conditions are irregular, because the count acts as the baron’s witness while being known as his wife’s lover. According to Abel, the irregularity is mitigated since the baroness has been separated from her husband for three years. Pibrac’s wife, Agatha, interrupts to announce her objection to the Baroness de Morannes’ inclusion among the patronesses of an auction sale for the sake of charity, since this will open the door in high society for a woman with a bad reputation. The men respectfully decline to exclude her, then review the causes of the duel. At a masked ball, Savenay was in the baroness’ company when she reached out for her husband’s arm to provoke a deadly quarrel between the two men. The four men’s discussion is interrupted by the baron himself, who surprisingly refuses to pursue the quarrel, since this would imply defending his estranged wife. After the count and the baron leave, Abel expresses the view that the baroness sought Savenay’s life because of his intention to seduce her rival, the count’s wife, Jeanne. While Pibrac writes down the summary of the quarrel’s result, Savenay shows up, surprised to learn that he was defending the baroness. His sight is rather set on seducing the countess, who arrives from Etretat and notices that all the letters to her husband were left unopened. He presses her to accept his love, but she declines as her husband returns. But to her disappointment, he leaves soon after for the club. Learning of the countess’ arrival, her friend, Agatha, comes over and informs her about Savenay’s duel when they are interrupted by the count’s servant, requested to retrieve the written outcome of the duel. Jeanne finds it, only to discover that the duel was canceled and that both their husbands are involved as witnesses, Agatha believing that her husband may be the baroness’ lover, Jeanne denying that her husband might be so as the baroness enters to request funds for the charity event and is disagreeably surprised that the duel was annulled. At the club, Pibrac queries Abel about the availability of a dancer named Sunflower in view of his wife’s coldness. By mistake, Morannes receives a letter meant for Savenay from his estranged wife. When Morannes hands it over to Savenay, the latter recognizes the writing and so proposes that they read it together. Despite Morannes’ refusal, he reads it aloud, in which the baroness expresses outrage that the duel has not yet occurred. The men shake hands and leave the matter as it is. The organizer of the charity event, La Grézette, worries that Pibrac’s wife threatens to remove herself along with twelve of her friends unless the baroness is removed as patroness. La Grézette is all the more anxious after Abel informs him that to remove the baroness will turn him into Mauves’ “mortal enemy”. His anxiety further increases when Pibrac informs him that he will defend his wife unless the organizer accedes to his wife’s request. Yet Pibrac compromises himself when after accosting a masked woman assumed to be Sunflower, he discovers that it is his wife threatening revenge. After leaving, he is forced to return, locked out by his wife. Meanwhile, Mauves learns that both Savenay and the baroness intend to leave the city. He assumes that Savenay is chasing his mistress after courting her on the beach of Etretat when in reality the philanderer courted Mauves’ wife there. Anticipating the necessity of a duel, he is anxious to hand over to his rival the money he owes him but without owning the necessary funds. To his surprise, Savenay prepares to hand over a receipt stating that he received the money. Having heard the story from the baroness, Mauves insists on knowing the name of the woman he courted at Etretat. Savenay leads him to believe falsely that it was the baroness. By reading her husband’s letters, Agatha discovers that a doctor will join Pibrac in the matter of the duel. She tells the doctor that she expedited his letter to Jeanne. Meanwhile, Mauves seeks to discover who paid his debt, knowing only that it was a woman but not the baroness. At the charity event after a night of dancing at a ball, mostly with Sauvenay, Jeanne confronts him with the news of his impending duel with the baron, but he denies it. She concludes that he intends to fight her husband instead, but he denies that, too, until she proposes that he follow her to her husband, which he resists. She then guesses that the men will fight over the baroness, her husband’s mistress. “And so this woman spied on us? And so this woman saw that you loved me? And because she sends you off to fight, she knows that I love you,” she pronounces and promises to wait for him back at Etretat. To her husband, Jeanne admits that she indeed was the one who paid his debt, but, going out, takes her father’s arm instead of his. To mock her presence at the charity event, Agatha exposes a large set of dolls resembling the baroness, who, pretending not to notice, even offers to buy one. When Jeanne returns, she sees a humiliated rival and a husband immobilized because of her presence. As a result of the count’s sign of respect, she rejects Sauvenay. “I do not want to be one day what this woman is today,” she asserts. After learning that her husband is not the baroness' lover, she accepts him back home again.

Jules Lemaître

[edit | edit source]

Jules Lemaître followed realist footsteps with "L'âge difficile" (The difficult age, 1895).

“Jules Lemaitre...[wrote] fine, if not particularly dramatic, studies of infidelity, political opportunism, invalidism, and old age, most notable in The Difficult Age” (Gassner, 1954 p 409). “With The Difficult Age, Lemaître gave proof of his command over the dramatic medium. With perfect ease he conducts his hero, a man of middle age, through dangerous love affairs, and entertains us with a series of delightful genre scenes. Those parts of the play dealing with the Indian summer of Chambray, his meeting an old sweetheart after many years of separation from her, are handled with great dexterity and gentle tenderness” (Clark, 1919 pp 129-130).

“What with her husband, an adventurer, and her father, an old knight of the pavement, whose moral sense has entirely evaporated in thirty years of fete, Yoyo is a highly amusing little rascal, but as repulsive as the heroines of M Jean Jullien and Paul Alexis...Throughout The Difficult Age, there is a ceaseless flow of wit without in any way detracting from his delicate moral perception. The explanation between the faithless Pierre and his wife, Jeanne, at the beginning of the second act is perfectly delightful, and would be a masterpiece of truth and comedy if its admirable beginning did not tail off into pedantic and somewhat wearisome argument. But to explain the title of the play, I must say one word about the principal character the character that makes the play. Which is the difficult age? The sixtieth year. Doubtless this age is not difficult to the man who understands how to grow old, and who has been careful to lay up a store of affection for the time of life which cannot hope to gather in fresh harvests. But it is a difficult age for the old bachelor, who consoles himself with left-handed paternity, and is forced to intrude upon other people's happiness if he is to win any for himself. When he sees that he is de trop, he rushes headlong into another danger: Yoyo. These two syllables suggest such a mingled aroma of childishness and corruption that I need not go on. What can save him from Yoyo? The friendship of a pure and innocent woman, rising out of the dead ashes of the past, and ready to resume a dream rudely broken off thirty years ago. Placed between the saint and the good-for-nothing, he chooses the saint. But, unfortunately, she is infinitely less real and life-like than the other, and one fancies that Yoyo will live longer in the memories of spectators of all ages” (Filon, 1898 pp 189-192).

“The individual note...which M Lemaître has contributed to the drama of his period is that of a sane and liberal humanity...Hence the surface of his dramatic work is never hard and brittle but always suffused with the warm glow of life. His understanding charity embraces the "fault" of Mme de Voves in Revolted (1889) and the almost attractive corruption of Yoyo -significant syllables!- in The Difficult Age...[The play] is a satiric treatment of a sufficiently tragic subject, the loneliness of age. But here, as elsewhere, the wise and tender humanity of M Lemaître sounds its clarifying and reconciling note” (Lewisohn, 1915 pp 90-94).

“The very openness of mind of Jules Lemaître, his freedom from prejudice, his admirable integrity, render impossible any categorical summing up of his philosophy of life. He is at once skeptic, believer, poet, politician, republican, and royalist” (Clark, 1919 p 136).

“The difficult age”

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1890s. Place: Paris, France.

Text at ?

Jane Martigny receives the visit of a neighbor recently moved in the neighborhood, Mrs Meriel, interested in making her acquaintance. Jane explains that she and her husband, Peter, are living with her bachelor uncle, Chambray, who took charge of her after her parents died, founded a chemical factory, and accepted Peter as his associate. As Jane prepares to receive the visit of the Montailles, Robert and Yolanda, surnamed Yoyo, a convent friend of hers, along with Yoyo’s father, the count of Vaneuse, Chambray admonishes his niece for encouraging such relations. He has heard that the Montailles make a living by selling furniture and other household items to friends, who, in turn, sell them off at a cheap price to other friends who, in turn, sell them back to Robert, in particular an Italian Renaissance piece. He further insinuates that these favors are assured by the sexual favors Yoyo bestows on these friends. The count of Vaneuse arrives first after a 15 km tour on his bicycle. Vaneuse complains about the loneliness of old age as a widow, as does Chambray, who specifies that he only ever loved one woman, long ago, who promised to marry another man just as he was about to declare his love. Robert and Yolanda also arrive on their bicycle. Vaneuse disapproves of his daughter’s friendship with the disreputable Baroness Mosca. “Mosca amuses me because she is even more bored than I am,” Yoyo declares. “It is within the reach of anyone to look only for one’s pleasure to the point of no longer knowing where it is,” Chambray counters, “and to cross out duty from one’s life, and to love no one, and to be surprised at nothing, and to be bored, and to morphinize one’s self, and to distract one’s nerves, and to empty one’s brains”. When alone together, the financially troubled Vaneuse requests a 50 louis loan of his daughter, but though possessing no such sum, she promises to try obtaining it. She asks her lover, Peter, the sum of 150 louis, who agrees to yield that amount on the following day. As Robert carries in the Italian Renaissance piece, Jane guesses that her husband is one of Yoyo’s furniture friends. She reels and pushes her away. The following morning. Peter urgently wishes to speak to his wife and defend himself, but Chambray discourages such an attempt. Peter wants to discover how his wife could have guessed about the furniture business. Chambray says nothing. Instead, he offers his services in the event that Robert challenges Peter to a duel. After Peter leaves, Jane, in turn, expresses a wish to see her husband, but Chambray discourages such an attempt once more, insinuating that Peter has made light of the situation without requesting to see her. When she considers divorcing him, Chambray pretends to encourage a reconciliation with her husband but then quickly agrees to the divorce plan and suggests that the two may still continue to live together. After he leaves, Peter arrives to ask her pardon. She is unwilling to forgive him until he pretends to announce his forthcoming duel with Robert. When she cries out in fear at the lie, Peter is certain that she still cares for him. He discovers that Chambray is the man who told her about the furniture friends and husband and wife are reconciled. Resenting Chambray’s interference, Peter accuses him of being jealous of his own niece and asks his wife to choose between the two. She chooses Peter. Crushed with surprise, Chambray offers to leave the house. Instead, Peter proposes that he and his wife move over to a pavilion next to the factory. Left alone, Chambray receives the visit of Robert, who comes over to complain about his case and to announce his intention to challenge Peter to a duel. Chambray replies sarcastically to the extent that Robert is goaded to challenge him to a duel as well. But when Chambray insinuates that he knows all about his business affairs and is ready to reveal them, Robert offers to take him on first, which Chambray accepts. The duel results in Robert receiving a wound in the face from Chambray’s sword, at which news Peter demands to know why he took his rightful place and has refused to see him, his wife, and his two children. Chambray responds by denying that the duel had anything to do with Peter. After hearing Peter’s clumsy explanations about the feelings he and his family have for him, Chambray dismisses him. Hearing of the separation, Vaneuse next comes over to ask him to receive a visit from his daughter. He accepts. Yoko asks his pardon for hurting his niece and attempts to insinuate herself in his good graces. She places her hand over his and rubs herself against him. “Take me to defend me, to make me better, to elevate myself at your level,” she pleads. While hearing Jane’s name cried out outside, he declares: “all of this means that you do not hold a penny in hand and that you are a delicious hussy.” The sudden insult makes her faint. Untightening her bodice, he watches Yoyo recover and agrees to become her friend until he receives the visit of Mrs Meriel, whom he discovers to be the woman he once loved as a youth and who convinces him to be reunited with the Martignys.

Octave Feuillet

[edit | edit source]

Octave Feuillet (1821-1890) trod a similar path as Curel, Augier, Gondinet, and Lemaître, though a softer one, with ”Chamillac” (1886).

In La Crise (1854), [Feuillet] gave evidence of his skill in gratifying the nibblers at forbidden fruit without shocking the moralists, contriving, from the reconciliation of husband and wife, to squeeze as much excitement as from the clandestine meetings of wife and lover. Having dramatized his well-known fiction, Le Roman d'un Jeune Homme Pauvre (1858), which set all Paris to weeping, Feuillet began to write directly for the boards. La Tentation (1860), a triangular play with a virtuous conclusion, was followed by Montjoye (1863), a sparkling comedy of character, and by La Belle au Bois Dormant (1865), a fairy tale transposed into modern terms. Increasingly, Feuillet revealed the influence of Dumas fils, especially in Julie (1869) and Le Sphinx (1874). The heroine of Le Sphinx, falling enamored of the husband of her friend, struggles against his indecision and the resentment of his wife. Though prepared to poison the latter, Blanche impulsively takes the fatal draught herself, dying, as a modern Phaedra, the victim of love. Thus virtue triumphs, though logic suffers. Feuillet, indeed, was intent upon exploring the vagaries of passion rather than illustrating a moral law; here and in such pieces as Le Pour et le Contre (1853) and Le Cheveu Blanc (1859), it was difficult for him to conceal his fondness for the wantonly suggestive. Occasionally, however, he atoned for what was insidious by a drama like Le Village (1856), notable for its idyllic charm. Delicate rather than robust, Feuillet was a feminine soul, sensitive and sentimental" (Chandler, 1920 p 21).

"Of a delicate, refined nature, emotion- all in thought while retired in life, a prey to extreme nervousness, which finally shattered his health, he avoided in the main the realistic views of human existence and sought refuge in the realm of romance. He wrote especially for the society of the Faubourg St Germain, and gained its favor by his elegance of diction and of phrase. Throughout his writings he seems to have steadily aimed at moral teaching, based on modern manners as he found them. Neither profound nor broad in his delineation of social life, he yet brings to his work the same notion of chivalry which was applied to other times and lands by one of his favorite authors, Walter Scott (Warren, 1891 p 63).

"Chamillac"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1880s. Place: Paris, France.

Text at ?

A portrait painter, Hugonnet, is surprised to find his student, Sophie, whom he thought away at Le Havre. While a ballet dancer several years ago, she was abandoned by a lover and taken up by Chamillac as her protector, though not her lover, promising to pay for her studies and then marry her after a period of a few years. But she suspects Chamillac loves a woman of the world and so, pretending to go to Le Havre, she spied on his activities and believes her rival to be Clotilde La Bartherie, once courted as a married woman but then abandoned by an army officer, Robert d’Illiers, now the fiancé of her husband’s widowed niece, Joan de Tryas, whose portrait Hugonnet is working on. Sophie recognizes Joan as the woman who once accepted to dance with her in a quadrille at a casino hall when everyone else rebuffed her as if she were a courtesan. Hugonnet expects Joan for her session at any moment, but when the doorbell rings, an intimidated Sophie hides behind a curtain. Joan enters accompanied by Robert, her fiancé and cousin, and her brother, Maurice. Robert considers Joan’s portrait pretty but with a face too active-looking and too bold. Joan and Maurice disagree that the painter should change her face. Hugonnet is next irritated on learning that Joan has invited her uncle, La Bartherie and his wife, Clotilde, who in turn invited over three members of her charity group, a countess, a baroness, and the secretary of the group, Carville, who all laud the painting, only La Bartherie, the countess, and the baroness consider the facial expression as too sleepy-looking. On learning that Robert has the opposite opinion, Clotilde cries out: “You always want to snuff everything out.” Clotilde is disturbed at the rumor that Chamillac intends to marry beneath his social rank. Hugonnet defends Sophie and informs Joan that the woman in question is the one she danced with at the casino. “I hear but I don’t understand” Joan comments, “because this girl is nothing at all.” Clotilde promises to shame Chamillac and break off that marriage plan. When the two leave, a distraught and agitated Sophie emerges from behind the curtain and faints. At La Bartherie’s house, Maurice tells Joan that he suspects Chamillac of being in love not with Clotilde, as some think, but with her. “First, she had a weakness for Robert and you marry him,” he comments, “then she throws herself at Chamillac and you absorb him.” His sister laughs off his suspicions. Robert shows up with news he disbelieves, that his fiancée was seen arm in arm with an actress. To his consternation, she explains that the news is partly correct in that she invited an actress to walk alongside her under her umbrella in the rain. When alone with Clotilde, Robert demands to know why she appears so hostile to him. “It amuses me,” she retorts. Robert defends his breaking off their illicit relation by her failure to encourage him, but, in her view, he should have persisted. She is joined by her husband, Louis, president of the charity group, along with the countess, the baroness, and Carville, its regular members and Chamillac, a new member, to judge of individual cases, notably Lucian Gaillard’s, seen in a barroom playing billiards and consorting with frivolous persons. When Lucien retorts to Louis that the same may be said of him, the latter angrily cuts him off from any further help. Although Chamillac takes Louis aside to plead for leniency toward Gaillard, the president refuses until forced to accept when reminded of his weekly visits to a certain house under a false name. Chamillac is invited with the rest to go to a ball but is intercepted by Maurice, anxious over his gambling depths: 30,000 and 40,000 francs owed to two members of their club, the latter being the amount due to Chamillac himself, which, if unable to pay, will disbar him from the club. Maurice pleads with Chamillac for more time, but he refuses. When Maurice confesses his dilemma to his sister, she offers him her diamond necklace, but he is too ashamed to take it. Late in the evening at Chamillac’s house, Hugonnet reveals what happened to Sophie at his studio, particularly her jealousy towards Clotilde La Bartherie. Hugonnet is relieved when the man who discovered his talent as a painter assures him that he has never had any amorous relation with Clotilde and will keep his word to Sophie, while adding nevertheless that he loves another woman he never will be able to obtain. When alone with Sophie, he reiterates his promise to her. She is relieved until learning that a woman has shown up to call on him at this late hour. Chamillac requests her to leave, but she refuses, and is then astonished at seeing Joan, who once befriended her. Confident that Joan’s presence could only be honorable, she leaves at once. Chamillac guesses that the purpose of her visit is to plead for her brother. He reveals that he has already paid the 30,000 franc depth to the other man and offers to forget the 40,000 franc depth owed to him, refusing him at first only to teach him a lesson. Joan is grateful for his intervention but insists that her family will pay back the entire sum. Their talk is interrupted by Robert, pushing away a servant after discovering his fiancée’s riding vehicle in front of his house. Robert demands to know the purpose of her visit, but she declines, instead requesting Chamillac to reveal it as she leaves. Chamillac declines as well, so that both men can only agree to fight a duel the following day over the unsolved secret. Back at La Bartherie’s house, Maurice and Joan’s father, General La Bartherie, hears from Clotilde about Chamillac, whose father was once a friend of his and who was a soldier under his orders. Unexpectedly, Robert shows up to say that circumstances no longer permit him to remain his daughter’s fiancé. When the general asks her the reason, she confesses it is because of her visit at Chamillac’s house late at night but refuses to reveal the motive. He violently seizes her by the arm until Maurice enters to confess his gambling debts. Taken aback by this confession, Robert retracts his withdrawal, but, after hearing Joan’s anger at his mistrust, he marches off. Joan receives the visit of Sophie, who reveals her fear that Chamillac intends to marry her only from a sense of duty, not love, and so proposes to quit the field to her. But Joan retorts that she has merely a sympathetic regard for the man. Sophie then reveals the main purpose of her visit, that Chamillac was stricken down in a duel with her ex-fiancé. The general has also heard the news and now insists on knowing the relation between her and Chamillac. She repeats what she said to Sophie. “There may never be anything in common between you and Mr de Chamillac,” the general declares. Seven weeks later at Chamillac’s house, the recovering duelist receives the usual visit of Hugonnet and Sophie, now married to each other, followed by General La Bartherie, who requests Chamillac to reveal why his marriage with her daughter is impossible. Reluctantly, Chamillac confesses before him and Joan that as a young man he was gambler much like Maurice and, in a fit of despair at his mounting debts, once stole an envelope containing 15,000 francs from the general’s desk. The general discovered the thief, who took means to die in battle the following day, when he became severely injured but survived, since which time he has devoted many hours to works of charity. “I wanted to impose the supreme expiation," the general declares. “Go, kiss your wife.” Chamillac embraces Joan.

Emile Erckmann and Alexandre Chatrian

[edit | edit source]

Other realists in the same vein include the duo of Emile Erckmann (1822-1899) and Alexandre Chatrian (1826-1918), who wrote "Les Rantzau" (The Rantzaus, 1882), adapted from their novel, "The two brothers" (1871), who carry on a vendetta for many years because their father's will favored the elder. The Erckmann-Chatrian team also wrote a more melodramatic piece, "The Polish Jew" (1867), adapted in the English theatre by Leopold Davis Lewis (1828-1890) into "The bells" (1871). Fifteen years ago, Mathias incurs financial troubles and is in danger of losing his inn when he meets a Polish Jew whom he hacks to death with an axe for his money. One day, he faints when another Polish Jew enters his inn to warm himself. His joy in beholding his daughter's marriage is spoiled by dreams of being taken to court for murder. On the marriage day, he falls into a fit and dies.

"The geographical and emotional center of the works of Erckmann-Chatrian can be marked with considerable precision: it is a section of the western Rhineland, a narrow strip of borderland between Alsace and Lorraine, extending from the summits of the Donon and the Schneeberg on the south (at about the latitude of Strasbourg) to Fénétrange and La Petite Pierre on the north. In this region, the Vosges are red sandstone, rising nowhere to high peaks, but weathered into a tangle of precipice and gorge, intersected by narrow, winding valleys, and heavily wooded with fir and beech" (March, 1935 pp 370-371).

"The Rantzaus"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1829. Place: Vosges mountains, Lorraine region, France.

Text at ?

Thirty years ago, Anthony Rantzau’s will stipulated that most of his possessions were to go to his elder son, John, to the detriment of the younger one, James. Since then, the two brothers have been feuding. Most recently, John, now a rich farmer, purchased land between two strips of land belonging to James, meant to impede his brother’s business as a wood merchant. A day before his saint’s day, James’ son, George, surprises his old schoolteacher, Florence, with a gift: Jussieu’s "Dictionary of natural sciences" (1824). George complains of his uncle suing his father because of the land purchase. James, also the village’s mayor, follows his son in Florence’s lodging, swearing he will fight his brother irrespective of court-costs. When the arrival of John and his daughter, Louise, is announced, father and son immediately leave by the back-door to avoid meeting them. John gives Florence a heifer as a gift, which Louise herself took care of since its birth, which pleases Florence’s wife, Mary-Ann as well. "When women are happy, men lead a quiet life," John comments with a smile. John invites Florence to supper with Marry-Ann and their daughter, Juliet, on the following day. Also invited to the party is John’s friend, Paul-Luke Lebel, recently named guard general of waters and forest, whom he intends as his daughter’s husband. To bother his brother living next door, a man who hates music, John encourages Paul-Luke to sing aloud a romance, but the latter’s voice is drowned out when James begins loudly to thresh wheat in his barn. John takes Florence apart to ask him a favor. Fearing his hot temper in case of a refusal, he wants Florence to announce to his daughter his choice as her husband. Florence unwillingly accepts and is shocked on hearing that rather than submit to her father’s will, she would return to the convent of Molsheim where she stayed in her youth. When John learns of this, he lifts his hand to strike his daughter. Florence tries to prevent the blow, but then John turns his rage against him. "Save yourself, Louise, save yourself," Florence cries out. "He’ll kill you." John pushes him out and threatens to prevent her plan. He arranges to announce the marriage, with Florence forced to put up the sign on the door of city hall. To his disbelieving ears, Florence learns from a despondent James that George loves Louise and wants to marry her. When George next meets Paul-Luke, they agree on fighting a duel for Louise’s hand. Troubled by her daughter’s disapproval, Louise’ health deteriorates and her doctor fears the worst, so that John unwillingly goes over to his brother’s house to prepare for their marriage. When the agreements are drawn, George tears up the paper, pointing out that the agreement hurts both parties. Contrite, John and James finally agree to begin anew.

Gaston Devore

[edit | edit source]Another family conflict, "La conscience de l'enfant" (The child's conscience, 1899), is the theme of a drama by Gaston Devore (1859-1949).

"The child's conscience"

[edit | edit source]Time: 1890s. Place: Paris, France.

During a family party at the Cauvelin house, Eva worries that her lover and brother-in-law, George Montret, is compromising her by the way he looks at her. Thanks to his acumen, George is elated to report a successful return of her invested money. Their talk is interrupted by her husband, Emmanuel, an accountant, to whom George specifies his wife’s profit of 100,000 francs. Emmanuel admires George, who not only runs a factory but also “possesses the genius of speculation”. George asks John Richard, a researcher after the tuberculosis vaccine and intended of George’s daughter, Germaine, whether he is willing to look over the plans of John’s new bacteriology laboratory. He is. Yet Germaine’s grandfather, Mr Cauvelin, has heard rumors about George’s shady maneuvers and warns Emmanuel that he should prevent his wife from doing business with him as well as keeping a better watch over the coquette, both suggestions downplayed by his son. Cauvelin and John’s father, Mr Richard, confer about precipitating John and Germaine’s wedding despite John’s desire for a delay in view of his work. But alone with his father, John hesitantly accepts and convinces Germaine, though more like friends than lovers, that they should marry. To help out his business dealings, George asks his wife, Jenny, whether she accepts mortgaging her properties in Brittany, which she does without hesitation. Meanwhile, Cauvelin receives the visit of a certain Mr Servans, influential board member of George’s company, who informs him that George has been dealing fraudulently, taking company cash for his own investments. He replies that the accusation is the result of a misunderstanding between Servans and himself. The next day, Eva tells George that she has developed qualms about their relation and now wants to break up, to which he reluctantly agrees and promises to deliver her letters later in the day at their usual place of rendez-vous. John shows up next, now reluctant to accept money from George for his laboratory in view of the ongoing accusations. John’s father has read about the accusations in the papers and learned from George’s lips that the accusations are at least partially true. He now wants to annul his son’s wedding plan. Cauvelin defends the notion that the wedding plan should still go forward, to which John agrees, but not his father or Germaine herself, who, in any case, considers John more as a brother. Cauvelin can only convince Richard after expressing his determination to sever George from the family and marry off Germaine without her father’s money. Jenny is distressed about the potential cancellation of the wedding until her husband discloses that a group of bankers have decided to support him. In case they fail, a banker named Audibert, greedier than the rest, may also support him. However, Emmanuel tells Jenny that his father wants her to divorce George. In addition to the rest, Cauvelin has learned that George rents an apartment to receive his mistress. He knows the address but not the woman’s name. Jenny leaves to investigate at the mentioned address, intending to divorce if the rumor is true. Later, a distressed George discovers that the banker group has failed him, only Audibert being able to save him. He asks Germaine to hide a huge sum of money in her room at Cauvelin’s house as her dowry, but she declines the offer. Beginning to break down with worry, George accuses her of defending Cauvelin’s interests more than his. Unaware that the matter concerns his wife, Emmanuel tells Eva about Cauvelin’s discovery of George’s infidelity. Eva’s anxieties increase when Jenny reveals that she has found her husband’s letters to her in their apartment. Eva wants the letters back, but Jenny is determined to use them in the divorce proceedings. Cauvelin requests Emmanuel to tell George that Audibert insists on Cauvelin being part of the new board of directors, which he accepts on condition that George severs ties with both Jenny and Germaine. Jenny leaves her husband’s letters for Cauvelin to read, after which he repulses Eva’s wish to keep her husband in the dark. “I prefer a public scandal than an intimate shame,” he affirms. He next insists that George sign a paper relinquishing his rights as a father over to him. Despite Mrs Cauvelin’s disapproval of this request, George agrees to sign. After witnessing George’s farewell to his daughter, Jenny joins her mother in revolting against the request. An angry Cauvelin expresses his hate towards George. “If you hate me,” he asks, “why do you judge me?” “You accuse me of robbing you of what belonged to you in Germaine?” Cauvelin retorts. “I did it to save what belongs to me in her.” However, Jenny requests that her husband’s rights as a father be respected. When Cauvelin declines, she follows her bankrupt husband and then Germaine follows her parents. Months later at Montret’s house, Emmanuel informs Jenny that he, too, has left their father’s house and has decided to forgive his wife’s adultery. In the meantime, Germaine’s separation from Cauvelin has made her sick in bed. George has succeeded in re-establishing a good financial position. George and Jenny agree that Germaine must marry, although he thinks that only his father can convince her, a better outcome than the present one even if it implies losing her to him, which is why he invited him over. Jenny greets Richard and his son coming over in a surprise visit. Despite his unwillingness to ignore his father’s wishes, John still wants to marry Germaine and despite John’s willingness to forego Germaine’s dowry, she refuses to affront him by refusing it and refuses to accept without Richard’s consent. To her joy, Cauvelin arrives to take her with him, but she prefers to remain with her father. Observing Germaine’s love of her father and George’s humility and abnegation, including giving his fortune to the poor, Richard finally relents his opposition to the marriage.

Edmond Rostand

[edit | edit source]

Reacting against the realist mode, Edmond Rostand (1868-1918) wrote in the neo-romantic vein, notably "Cyrano de Bergerac" (Cyrano of Bergerac, 1897), based on the life of the 17th century writer and soldier (1619-1655).

"The historic Cyrano, born at Paris in 1619, was a soldier in the Gascon regiment of Carbon de Castel-Jaloux and a disciple of Gassendi, Campanella, and Descartes. Aside from his feats of valor in the wars, he fought many a duel and set Paris laughing by his bombast and his pranks. In his comedy, Le Pedant joue, he furnished Molière with two scenes for Les Fourheries de Scapin, and in his Histoire comique des estats et empires de la lune and his posthumous Les Estats et empires du soleil he composed delightful specimens of the fantastic journey to other worlds, destined to influence Gulliver's Travels. What in Cyrano chiefly appealed to Rostand was the confinement of a fair soul within a grotesque body. He would take this fellow of the bizarre nose and noble spirit, this egoist prone to roar down the timid and floor the strong, and show him gentle to the weak, tender to the fair, and self-effacing in love. It is the character of Cyrano, rather than the ingenuity of the plot, that makes the success of Rostand's play. Since the hero's vitality is superb, what matter that the story and its incidents be spun from the brain of a romancer? It is all of the stuff of which dreams are made, but lively, virile, and jovial" (Chandler, 1920 p 317). “The plot is fiction; the hero is of course not only historical but is recreated, from the evidence of his own writings and many scattered notices, with all learning, sympathy, and truth to tradition. Cyrano de Bergerac was the most striking of all the fantastic and independent figures that preceded the age of Versailles, the age of Racine, of measure, of perfect form. He was actually a duellist, a Gascon, a satirist of free, unchastened power, a noble free-thinker, a wit in several styles including the fashionable one of points and preciosity, and a dramatic creditor of Molière” (Elton, 1900 p 151). “The plot moves briskly, keeping the audience while engaging its sympathies in favor of the hero, then building to a double climax of considerable pathos. Each of the five acts has a dramatic unity of its own, yet together the acts form an almost seamless whole” (Doherty, 1986 p 1564).

In Henry James' view, "Cyrano doubtless never flourished in fact as our author makes him flourish in fiction, but the intensifications are of the right colour. With such things as these, the medium, as I have called it, is already constituted, the form is imposed, the style springs up of itself, and author and actor have but to keep them going. M Rostand has not missed an effect of high fantasy, of rich comedy, of costume, attitude, sound or sense that could be shaken out of them; and we scarce know better how to describe the whole result than as a fine florid literary [revenge] of wounded sympathies and of the old French spirit, or at least of the imagination of it- the French spirit before revolutions and victories and defeats had made it either shrill or sore. And such an account of the matter is none the less true even if it be not precisely easy to say [revenge] against what. Against everything, we surmise, that would have made the production of a Cyrano impossible anywhere but in France, where doubtless, moreover, such productions are, whether as revenges or as speculations, less and less to be counted on" (1949 edition, pp 321-322).

“Edmond Rostand wrote ‘Cyrano’ as a reaction against the realism and naturalism which has become ascendant in the plays and the fiction of the late 19th century...’Cyrano’ reveals what Rostand and the millions among his audiences miss in today’s world: selflessness and sacrifice, integrity and courage, elegance and honor” (Goldstone, 1969 p 12). "Cyrano of Bergerac" "purports to be a partial reconstitution of the spirit of the times portrayed, and is steeped in the preciosity of that period. In this style, Rostand, as an incomparable virtuoso of language and of rhyme, revels to the utmost. Hardly any one can read the play without being captivated by its magnificent swagger, by the animation of its scenes, by the poetry of its lines, by its sentiment, by the suffering love of Cyrano for Roxane, by the vigorous or graceful climaxes, by the wonderful, even though occasionally strained wit, with which it is sprinkled" (Wright, 1925 p 891).

“The plot built around the highly colored central personality and inspired by the legend of his heroism, un folds before us in a series of episodes, which move with unflagging verve and are elaborated with abundant poetic and dramatic ingenuity” (Burr, 1920 p 112). It is "a splendid play. The hero is a typically romantic figure grotesque in appearance and great of heart. There are certain fustian lines and unlikely situations, particularly in the fourth act. But the whole play is in the highest degree touching and stirring" (Wilson, 1937 p 146). "There is a mighty love interest; there is the imcomparable bravery and audacity of Cyrano, his strength of character, his chivalrous self-denial, his reticence to proclaim his love for Roxane, until well-nigh in his last breath the truth bursts out in the magnificent line: 'No, no, dear love, I did not love you'; there is the note of gaiety in the delightful couple of the Ragueneaus, in the boisterous young cadets, in the jovial monk; there is patriotism, jubilant at first, then glorified in the death of Christian; there is a glimpse into the splendid era of the sun king- in fine, everything to evoke smiles and palpitations and tears" (Grein, 1899 p 87).