History of Western Theatre: 17th Century to Now/Spanish Post-WWII

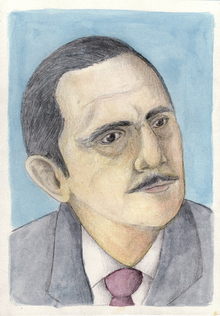

Alejandro Casona

[edit | edit source]

Alejandro Casona (1903-1965) continued commendable work from the previous era with “Corona de amor y muerte” (1955, The crown of love and death), yet another adaptation of the history of Peter I of Portugal (1320-1367) and Inês of Castro (1325-1355) following Montherlant’s “The dead queen” (1942).

“The Inés de Castro tragedy comes from the conflict between the king of Portugal and his son Pedro, the crown prince. The king, for political reasons, wants Pedro to marry Constanza, princess of Castile. Pedro has loved Inés de Castro and has had children by her. This love has transcended all parental and political opposition. In fact Casona has a strong suggestion that it is the very opposition which has welded a love which might not have been so constant. The king feels that he has no choice but to have Inés killed. In Casona's final scene, Inés appears to Pedro shortly after her death, presenting Casona’s philosophical speculations about death in a memorable manner. Death guarantees that the love of Pedro and Inés will never be threatened by time, force, or the withdrawal of force” (Moore, 1974 pp 53-54).

”The crown of love and death”

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1355. Place: Coimbra, Portugal.

Text at ?

Alfonso, king of Portugal, has invited the infanta of Castile to marry his son, Pedro, who, resisting this plan, has failed to show up. Suspecting that the prince is with his presumed mistress, Inês of Castro, a Spanish noblewoman with whom he has taken refuge at Santa Clara manor, the king orders his marshal to bring him over. When the prince obeys, Alfonso informs him that Inês will be sent farther away to one of his castles near Galicia and presents him to Constanza. When Pedro declares that he missed her arrival because of his only love, Constanza turns to Leonor, one of her waiting women, informing her that during the king’s hunt the following day that Leonor must pretend to lose control of her horse as a diversion while she visits Inês. At Santa Clara manor, Constanza advises her rival to abandon Pedro since she may sign a marriage contract already drawn between the courts of Portugal and Castile. Enraged at Inês’ continued resistance, Constanza draws a whip to mark her face but then throws it away. Unexpectedly, the king enters in his hunting garments, surprised to find the infanta in these premises. “Do not uselessly engage your authority,” she advises the king. “We have all powers except one. That one is enough for them.” But alone with Inês, he reminds her that she holds the key as to the peace between Portugal and Castile. “My only peace and my only war are called Pedro,” she retorts. They are interrupted by Juan, her seven-year old son. Knowing that the king may yield to her love-match in presence of her never-before-seen son, she leaves them together. But although the king and Juan play and part as friends, the unyielding king pursues his quest with the returning Pedro until his son informs him of his secret marriage with Inês seven years ago. The stunned king yet responds that the marriage can be annulled. “Hereafter, expect neither pardon no quarter,” he declares. In a meeting with his counsellors, he declares that the safest way to avoid war with Castile is to condemn Inês. The counsellors agree, even Pacheco, a favorite companion of the prince, all the more so when signs of revolt appear among the Portuguese populace. Successful in obtaining an annulment of the marriage contract, he king was requests his son to sign the document. Pedro refuses. “Behold the poor man God gave me as a replacement!” he exclaims to his counselors. “His ambitions are constrained in the limits of a bed-room. Pacheco warns Pedro that the more he resists, the more Inês is placed in danger. “When the knot cannot be untied, we cut it,” the king pronounces. To facilitate this purpose, the king orders Pedro’s arrest at the castle of Montemor-o-Velho and with his three counsellors head for Santa Clara manor to kill Inês. Her ghost appears to Pedro and when his associate confirms her death, Pedro leads a successful revolt against his father and becomes the new king.

Antonio Buero Vallejo

[edit | edit source]

Antonio Buero Vallejo (1916-2000) reached prominence with the gritty drama, “Historia de una escalera” (Story of a staircase, 1949) and the mystery drama, “Madrugada” (Before dawn, more precisely Dawn, 1953).

“Story of a Staircase" “which depicts the hopes and illusions of families in a Madrid tenement reflected the painful reality of the postwar period” (Halsey, 1986 p 276). “Buero’s drama portrayed the working-class people of a dilapidated Madrid tenement; the single setting of the unchanging stairway symbolized the fate of three successive generations who remained trapped in the same wretched situation. Incorporating a tragic portrayal of human existence generally absent from twentieth-century Spanish theatre, Historia de una Escalera represented a passionate but lucid judgement on Spanish society of the period” (Halsey and Zatlin, 1998 p 66). It "is a realistic drama dealing with the hopes and failures of three generations of inhabitants of a shabby apartment building in Madrid...The stairwell itself is a unifying element and an indelible visual symbol of the lives of the characters who can only move within boundaries dictated by social conditions or by their own self-delusion” (Holt, 1975 p 110). "Buero Vallejo often presents a dark picture of the world, attenuated by rays of hope. This is especially true in his early works. In 'Story of a staircase', he deals with the inability of his characters to break away from their oppressive social environment and lead a meaningful existence. In this highly schematic play, the stairway in an old apartment building represents the harsh material world that the tenants hope to change for the better. As the play begins, Urbano and Fernando, still young men, are discontent with their living conditions and hope for a better existence. Urbano, a worker, believes that through the labor union, by means of collective effort, this future betterment can be attained. Fernando, an employee in a small paper shop, hopes to be an architect, an engineer, and a poet, and to change the world by his own individual effort. Thirty years later, the stairway is still there; their hopes have not materialized; they are still living in the same building. Fernando is still a petty employee who has married, for money, a woman he does not love; Urbano, still a laborer, is married to Fernando's former girl friend who does not love him. At the end, in an ironic note, Fernando's son courts Urbano's daughter with the same words Fernando used thirty years earlier; he too hopes to be an architect, an engineer, and a poet. The implication is that these hopes, too, will not be fulfilled. In Story of a Staircase, the symbols of hope- the labor union and the architect/engineer/poet- achieve thematic relevance. In this play, Buero Vallejo equates spiritual transcedence, a desire for an authentic existence, with the achievement of social betterment. Quite appropriately, the labor union image suggests a collective attempt at edification, and the architect/engineer/poet image connotes an intellectual, spiritual renovation by means of individual effort. However, in a note of profound dejection and pessimism, Buero Vallejo seems to suggest that these endeavors cannot be fulfilled" (Ling, 1972a p 420). "Urbano and Fernando are complete failures because they talked and dreamed about what they were going to do, but did nothing to further their dreams. Some critics have blamed their failure on their environment, symbolized by the unchanging stairway, yet others in the play did manage to raise their standard of living, namely Elvira's father, and the 'Joven' and 'Señor' who appear briefly at the beginning of Act III. The latter three seemed well satisfied with their economic achievements. Urbano, however, placed all his hopes in his industrial union while Fernando considered himself a superior intellectual above menial work. Neither faced the hard fact of concentrated individual effort and struggle to inch ahead and break the chain that bound them to 'la escalera'...Before declaring his love to Carmina and while still indifferent to Elvira, Fernando already showed signs of his lack of ambition" (Giuliano, 1970 pp 21-22). In Buero’s view, the staircase “had clearly meant to symbolize the state of Spain at the time” (Dixon, 2018 p 281). “Space, and the life that developed within it, was to be tight, cramped, and restricted...Rather than a space outside the normal processes of life, the liminal stairway becomes their habitat, and therefore transgresses the boundaries of privacy to shape the residents’ lives through communal vigilance and internalized surveillance that reflect the social context of Francisco Franco’s Spain in the 1940s...The reader can estimate that the action transpires in 1919 (Act I), 1929 (Act II), and 1949 (Act III). Over those thirty years, the spectator witnesses the evolution of the relationships among three generations of residents of the stairway: Fernando is in love with Carmina, but instead marries Elvira, who is in love with him. Carmina ends up with Urbano, Fernando’s childhood friend. Urbano’s sister Rosa has a tormented relationship with Carmina’s lecherous brother, Pepe. The play ends with the two main couples’ children, Fernando, the son, and Carmina, the daughter, vowing to escape their uncomprehending community with words almost identical to those their parents, who are listening, once used” (Winkel, 2019 pp 113-114).

“Dawn” “is undeniably a skillfully wrought dramatic piece...[As Halsey (1973) first pointed out], parallels between dawn and Ibsen’s Ghosts are particularly notable. Both plays have a protagonist who undertakes a tragic search for truth about herself and about the past, and the symbolic stage effect of light flooding the room at the end of Dawn corresponds to Ibsen’s use of sunlight on the mountains in Ghosts. Without question, the most admirable quality of the play is its remarkably controlled form. The unities are strictly observed while a conspicuous clock records literally the playing time of the two acts as Amalia, working against time, seeks her answers” (Holt, 1975 pp 115-116), a perfect fusion of stage time and real time and adherence to the classical unities” (Lott, 1976 p 362). "Amalia, who felt a coldness developing in her husband Mauricio's attitude toward her, was unable to find out the reason for it before his death. Feeling that it was the result of gossip spread by one of his relatives before his death, she called them to her home minutes after his demise, pretending that he was still alive but liable to pass away at any moment. She attempts to extract the truth, promising that she will not permit her husband to leave her his wealth, but to leave it to them instead. By playing on their lust for money she finally discovers that her conjecture was correct, and, moreover, that her husband had loved her deeply to the end. Amalia had been the mistress of a painter before becoming the mistress, and later, wife, of Mauricio. His death meant wealth for her, but, this was of no importance. She was tortured by the thought that he had married and left her his fortune merely as payment for services rendered. She loved him profoundly and had to find out if he had still loved her up to the time of his death. Her bold plan was successful, and the knowledge that she was still united to Mauricio even in death gave her the strength to continue living. Her supreme effort, and the depth of their mutual love made Amalia, in Buero's ideology, reach the zenith of feminine accomplishment" (Giuliano, 1970 p 25). The play “portrays the intricate and well-planned battle of wits in which Amalia engages her husband’s relatives, whom she summons to learn the truth...Elements which underscore the mounting tension during her contest with the relatives are, first, the presence...of the dead body, with the imminent risk of discovery by the relatives, and, second, the pressure of time. Since Amalia knows that, in an hour and a half, the friends who will come to arrange the wake will reveal that Mauricio is already dead, she essays to trick the guilty person into betraying himself under the stress of the minutes which tick by. The relatives, meanwhile, try to prolong the battle in the hope that Mauricio will die before signing the will, and two of them even plot to murder him...The jealousy, greed, and hatred of the relatives gradually come to light...Amalia learns the truth...and this truth signifies the complete triumph of her love. Mauricio omitted Leandro and Lorenzo from his will because they both slandered her” (Halsey, 1973 pp 59-61). “The child-like status of women is often portrayed as a positive thing in the plays, and this is frequently contrasted with the manipulations of wilier, worldly-wise more ‘adult’ women. It is true that some of Buero’s early plays contain female protagonists, but in La tejedora de suen ̃os, Casi un cuento de hadas (1952), Madrugada (1953), Irene, o el tesoro (1954) and Las cartas boca abajo (1957), these protagonists are portrayed somewhat negatively, often as weak or delusional, and dependent on men for purpose and definition. Moreover, these female protagonists are generally not found responsible for their own weakness; men are presented as both the cause of their problems and the solution to them” (O'Leary, 2011 p 695).

”Story of a staircase”

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1919-1949. Place: Madrid, Spain.

Text at ?

When an electric bill collector shows up in an apartment building, Generosa, Paca, and Elvira pay, but Asuncion cannot. To save Asuncion from having her electricity cut off, Elvira’s father, Manuel, pays the bill. Elvira is thankful for this generous gesture, because she loves Asuncion’s son, Fernando. She requests her father to hire him and take him away from his low-paying office job, although he considers the boy a good-for-nothing. Paca’s son, Urbano, encourages Fernando to think over the possibility of organizing a union, but the latter prefers the thought of getting ahead by his own efforts. When Paca notices Generosa’s son and a pimp, Pepe, near her daughter, Rosa, she threatens to hit him with a frying pan, after which Urbano threatens to throw him downstairs. When Elvira asks Fernando’s help in purchasing a book, he roughly sends her away, loving instead Generosa’s daughter, Carmina. Ten years later, on the day of the funeral of Generosa’s husband, Fernando and Elvira, the latter with an infant on her arms, creep on the staircase while Pepe is scolded by his wife and part-time prostitute, Rosa, for failing to bring in money, flirting instead with Paca’s other daughter, Trini. The latter scolds him for failing to show any feeling on the day of his father’s funeral. Soon after, Urbano threatens him for coming near Trini, possibly to make a whore of his wife’s sister, too. In view of the dim prospects of Generosa and Carmina, Urbano proposes marriage to Carmina and is accepted. Although he has disowned Rosa, her father, Juan, helps her secretly by handing over money to Trini so that she can pretend it is hers to give. But she instantly reveals the secret to her sister. With Elvira complaining of her husband’s continued attachment to Carmina, Fernando is stunned on seeing Urbano and Carmina step into the landing hand in hand together. Twenty years later, Carmina and Fernando admit to their 12-year old son, Manolin, that they had no money to spend on his birthday cake. Manolin spies on the meeting between Urbano and Carmina’s daughter, young Carmina, and Fernando and Elvira’s son, young Fernando, who asks why she has been avoiding him. “This afternoon, we can meet where we did like last time,” she answers. When he wants to know more, she confesses that her parents refuse to accept him as a son-in-law. “Forget about us; forget about our plans,” she now says. When Manolin tells old Fernando about his brother kissing young Carmina, he is angry, mostly because of his wife’s disapproval. Pepe has left Rosa, so that she and Trini, who never married, remain alone. Over the years, Urbano and Carmina have been disappointed. “Why did you marry me me if you didn’t love me? Urbano asks. “I never deceived you,” Carmina responds. “You insisted.” Urbano and Carmina tell Fernando that they consider his son as great a loafer and coward as he is. Elvira embarrasses her husband by telling Carmina: “You think I took him away from you? Well, you can have him back any time.” Still willing, young Fernando wants to leave the building and start over with young Carmina, repeating ambitious words very similar to those of his father years ago. Young Carmina is now enthusiastic while her parents and his look down the staircase with sad eyes.

”Dawn”

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1950s. Place: Madrid, Spain.

Text at ?

Amalia’s husband, Mauricio, a picture artist who amassed important sums of money, has died of a heart attack and she has called his family over to their house without informing them of his death. Since the attending nurse is sleeping and must leave at 6 AM, she has until that time to obtain information from them. She wonders why Mauricio left money in his will only for her and one other. Mauricio’s sixty-year old brother, Lorenzo, shows up first, followed by his brother, Damaso along with Damaso’s wife and daughter, Leonor and Monica. “You two will be prize fools if you let her take anything out of this house,” Leonor tells Damaso and Lorenzo about Amalia, whom they suppose to be Mauricio’s unmarried lover left destitute because no will was left. Lorenzo’s estranged son, Leandro, next shows up, who defends Amalia when Damaso and Leonor desire that she should leave. Amalia says that they should be quiet to avoid waking Mauricio from his coma. “Why not?” Leonor asks. “Because if he wakes up,” Amalia responds, “he’ll sign the will I have prepared.” She says that the will states that he left everything for her and nothing for them. When another of Mauricio’s brothers, Mateo, left for America, there was a farewell party, at which one ofv them took Mauricio aside to tell him something serious about her. “Whoever that person was will repeat here and now word for word what was said,” she pronounces. “Otherwise, I’ll awaken Mauricio and he’ll sign the will.” Leandro proposes that she should try to wake him as Monica rushes to the adjoining room, soon captured by her father to prevent her from doing just that. An exasperated Leonor slaps her face for this aborted attempt. No family member speaks up as Amalia’s servant, Sabina, pretends that Mauricio is stirring in his bed. While Damaso, Leonor, and Leandro bicker, Lorenzo falls asleep. To everyone’s surprise, Leandro’s second cousin, Paula, rings the doorbell, who was absent at the party. To Amalia’s relief, Paula explains that she obtained news from a sculptor that Mauricio was dying, not dead. But to Amalia’s repeated inquiry, the family still fails to respond. Fifteen minutes later, Sabina catches Monica intending to revive Mauricio and takes her away. Likewise, because of his love for her, Leandro’s wish is also for Amalia to revive him. Sabina pretends to inform Amalia that the nurse is ready to give the patient an injection that might revive him, a lie that augments pressure on the family to speak up. Leonor confesses that they asked Mauricio for money. “We’re beggars,” Leonor says while turning to her husband. “That’s what you turned us into.” She admits to receiving money from Mauricio without informing her husband. “I talked about your clothes, your jewels, and all the things you’ve taken- stolen really- from the rest of us,” she tells Amalia, telling Mauricio she is a “common whore”. Paula intercedes to say that Leonor might have said something more specific, such as cheating on her lover, but Leonor denies she said such a thing. Monica whispers to Amelia that she saw Lorenzo taking Mauricio aside. Lorenzo only admits he asked for money, too, but was denied, but that Monica also took Mauricio aside. However, her story is similar to Lorenzo’s: she also asked Mauricio for money, but only on the part of her parents, and was denied. Paula tells Amalia that she knows the reason behind her fear, that someone had revealed to Mauricio that she and Leandro were lovers. “Won’t you tell her that you love her,” she confronts Leandro, “that I was just a little fling and that she should believe you? “She’s afraid that he really might not sign a will that gives her everything” Paula tells the others, “because she doesn’t know whether he believed she was unfaithful.” Amalia says he was not. With Amalia away, Leonor considers that this matter is advancing to their advantage, rattling her bracelets to wake drowsy Lorenzo, who interrogates the nurse but fails to guess that Mauricio is dead. Alone with Damaso, Lorenzo’s face changes to a determined look, proposing to end the matter by choking out what little life is left to Mauricio. Damaso only accepts to act as look-out. With Lorenzo inside the room, Damaso is discovered in a compromising position by Monica, who ruhses inside as Lorenzo comes out. “When I got in there,” Lorenzo avers, “He was already dead.” “They’ll never believe that,” Damaso retorts. With everyone back including a downcast Monica, Damaso, in a panic, reveals that Lorenzo entered the room on his own. Leandro finally reveals that his father was the one who spoke to Mauricio. “He wanted money if you and I married,” Leandro tells Amalia. “And because I turned him down, he lied about us that afternoon.” Lorenzo counters by stating that Maurio had received an anonymous letter that day, which he knew to be from Leandro, warning him to keep an eye on Amalia. Leandro hotly denies it. “I wanted something to come between you two, because I wanted you for myself,” he tells Amalia, “but I didn’t write any letter.” However, Paula contradicts him by producing that letter fetched from his coat-pocket. When Monica states that Mauricio is dead, everyone except Amalia considers Lorenzo a murderer until he questions the nurse as to the patient’s time of death: 3:30 AM. The family’s joy ends when Amalia announces that she and Mauricio were married, and so she gets all the money from his will except shares left for Mateo and Monica. “And for the two people who have told lies about me,” she says turning to Lorenzo and Leandro, “nothing.”

Alfonso Sastre

[edit | edit source]

Another playwrights emerging in the Spanish post World War II period includes Alfonso Sastre (1926-2021), author of "Ana Kleiber" (Anna Kleiber, 1955), “a love drama recalling “O'Neill and the experimental techniques of the expressionists” (Pronko, 1960 pp 113).

“Three full-length plays written in the mid-50s, Ana Kleiber, La sangre de Dios, and El cuervo are characterized by experimental, non-Aristotelian forms and a nihilistic ideology. They notably lack the socialistic perspective generally associated with Sastre's theatre" (Anderson, 1972 p 840).

“Anna Kleiber” features a couple unable to live apart but also unable to live together. There is excitement and togetherness in initiating but not in maintaining the love relations...an image of a humanity suffocated by its own existence (Corrigan, 1962 p 22). "The play is essentially a case study of a woman whose sadistic and masochistic compulsions lead her to destroy herself and all who come into contact with her...The source of the repeated separation of the lovers is Anna’s perverse character which causes her constantly to undermine the very love and tranquility she seeks...Anna is neither the victim nor the product of the war around her. She is, rather, the victim of herself and of the dark forces that make suffering inevitable in human life. Sastre’s real subject...is the inadequacy of love for human fulfillment” (Anderson, 1967 pp 77-79).

"Although dramatic tragedy runs afoul of bureaucratic optimism and vanguard nihilism, it attempts to propose to the spectator the double theme which Sastre feels is fundamental, that of an existing concrete condition in which man is surrounded by anguish, pain, and death, and that of historical reality, where man participates in the development of humanity towards more just conditions. Dramatic tragedy involves theater which aims neither at the individual (bourgeois theater) nor the collective mass (political theater)" (Schwartz, 1967 p 344).

"Anna Kleiber"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1920-1940s. Place: Spain, Germany.

Text at ?

Alfred, a philosophy student, encounters by chance Anna, an actress about to jump off a bridge. He convinces her to abandon thoughts of suicide to follow him. Although disgusted at the man, she once copulated with an impresario named Charles, in her words: "just to see how low I could sink." She warns Alfred not to concern himself with her, yet they live together for eight days until she suddenly decides to leave, a letter left behind stating only this: "I have come to love you so much that I can't keep on with you." In no way discouraged, he succeeds in finding her in Charles' acting company. As the two talk, Charles shows up and makes ambiguous comments on her personality traits. Unable to tolerate any form of ridicule concerning her, Alfred fights with him, each bearing a knife, and succeeds in stabbing him to death. A prompter arrives and proposes to take care of the matter provided Alfred join the Nazi party, Charles being a Jew and so in his view worth killing. Instead, Alfred shifts away to Berlin while Anna takes to alcohol and as a result is fired from an acting company. Alfred finds her again by chance at a public park, but when war is declared he joins the troops. To his surprise, she is happy to hear these news, since the interlude offers her the chance to live more intensely rather than the vapid way she has carried on so far. But with Alfred away to war, Anna takes instead to a derelict aimless life. When he returns, she admits the waiting bored her. Even together, she still shows signs of apathy and Alfred quickly grows tired of it. She wants to be punished, but he is unable to provide even that, until, goaded, he strikes her with a poker and is arrested. They eventually write to each other, but just when they are about to live together again, she has a heart attack in a hotel and dies.

Lauro Olmo

[edit | edit source]

Lauro Olmo (1921-1994) contributed in an important way to the period with the social drama, "La camisa" (The shirt, 1962).

The Shirt "is a vivid and moving account of thee existence of an element of Spanish society, with all the natural color and the bluntness of speech of the semi-educated captured in the dialogue. Although distinctly tragic in tone, the play is not lacking in lighter frequently earthy elements that provide balance in the playwright’s realistic and credible dramatic situations” (Holt, 1975 p 149). In The Shirt, "the playwright explores the shantytown existence of proletarians in a Madrid slum. Alienated from the economic mainstream, they are forced to consider emigrating in order to survive. (During the 1950s some 300,000 Spaniards emigrated to Germany, Switzerland, and France to work in construction, in factories, in service industries, or as domestics) In the play's focal speech, Lola, the protagonist, laments: 'when we got married we came to live temporarily in this makeshift shelter ...Do you know what it is to see a man cry?...The days without heat, the patches always temporarily...seventeen years have passed...too many...the best...with them our youth has vanished'" (Donahue, 1983, p 113).

The Shirt "focuses on two major problems of the 1960s: unemployment and the emigration of Spanish workers to find jobs in the industrialized nations of northern Europe. Olmo’s characters dream of winning the football pools or of emigrating, topics of avid discussion in the bar where they meet to escape the squalour of their hovels. The dilemma of whether to remain in their own country, where they were convinced that they had a right to be able to work, or to leave for exile was a problem shared by both shantytown dwellers and intellectuals during the Franco years. Juan’s conviction that it is in Spain where the real solution must be found reflects the personal stance of Olmo, Buero, and other committed dramatists who stayed in their native land. La Camisa is much more than a play about Spain’s poor and their lost dreams and illusions; the hope expressed in the work is universal” (Halsey and Zatlin, 1998 p 70).

The play is "set, not in a tenement of a Madrid, as is the case with many post-war plays, but in a [hovel] of a shanty town on the outskirts of the city. Although Juan is a skilled mason, he has no job. The play surpasses in social criticism anything previously [seen] on the Spanish stage...The poverty of the men...is the direct result of the economic structure in Spain...Juan's failure to find a steady job and his wife's subsequent emigration are prefigured when the former tries on the old and torn white shirt which Lola has found in the Rastro and the stiff collar which the grandmother has kept in her trunk ever since her husband's death...Lola is fully aware that Juan's final effort to obtain steady work will fail. The train stations are full of Spaniards who also put on their best shirt to apply for a job before deciding to leave. Afraid for her children's future, she finally determines to go to Germany herself, over the objections of her husband...For Juan, the solution- personal or collective- is not emigration. With a deep conviction of his right to work, he insists that since his employment record is good, his boss must heed his request...To Juan, moreover, emigration is both cowardly and unpatriotic...The white shirt, hung on a clothesline in full view at the beginning of the third act and torn in half by Juan in a fit of rage after the boss refuses to see him, symbolizes the former's hopes and failure. Underscoring this failure is the success of Lolo, who wins the football pools" (Halsey, 1979 pp 71-74).

"The shirt"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1960. Place: Madrid, Spain.

Text at ?

Agustinillo’s grandmother scolds the boy for wanting money to buy firecrackers when his father, Juan, does not even own a white shirt to ask his boss for temporary work as a bricklayer. To obtain money, Agustinillo distracts an attractive pedestrian by pretending to lie hurt on the ground while his friend, Nacho, lifts up her skirt so that Mr Paco, a bar owner, can get an eyeful of her undergarment. But instead of handing over the promised 5 pennies, he hands over only half a penny. The boys agree that their load of 5 firecrackers is insufficient to scare people. Nacho accosts his girlfriend, Agustinillo’s 14-year old sister, Lolita, who enters their house to avoid her brother’s teasing. Irate at being laughed at, Paco slaps Agustinillo while Nacho hides. Juan’s friend, Sebas, announces that, discouraged about work prospects, he is emigrating to Germany. Juan is disgruntled at these news. His neighbor, Maria, tired of seeing her husband, Ricardo, arrive home in a drunken state, hits his head with a frying pan, then panics when she thinks him dead. But he recovers with the help of their neighbor, Balbina. Juan’s brother, Maravillas, a balloon merchant, has trouble selling his wares until a drinking buddy of his, Lolo, buys 4 out of pity. Juan’s wife, Lola, has bought a new shirt. Though the collar is missing, it can be tied with one they already have, and though the tail-end is missing, too, any old rag can complete the garment. Yet, doubting that her husband’s request will succeed, Lola plans to head to Germany alone to find work as a house-maid, helped out by Balbina and her mother-in-law, the latter yielding her burial money for train fare. Knowing about the family’s troubles, the libidinous Paco tries to convince Lolita to work as his wife’s help-mate, but she slaps his hand away and refuses. After several people in the neighborhood watch an American satellite pass overhead, Maravillas releases his balloons, hands them over so that others may do the same, and exclaims: "Long live Spain!" At this point, Agustinillo and Nacho seize the opportunity of exploding their firecrackers and running away, but are captured by an angry Juan. Paco seizes Agustinillo while Nacho escapes. A helpful neighbor, Luis, hands over his belt to Juan, but he refuses to punish his son. Later, in a drunken stupor, Ricardo hits Maria, and so it is her turn to need Balbina’s care. Maravillas is worse than he ever was after learning of his wife’s death. Meanwhile, Juan is turned away by his boss’ secretary. Incensed, he rips his shirt as soon as he reaches home and leaves it hanging on a clothes-line. To everyone’s surprise, Lolo wins a huge amount of money in a soccer lottery after guessing correctly the outcome of all 14 matches. Juan watches dispiritedly as Lola heads for the train station with Maria uselessly clamoring in her ears that she wants to join her.

Jerónimo López Mozo

[edit | edit source]

Also of note in late 20th century Spanish theatre is Jerónimo López Mozo (1942-?), author of "Eloides" (1996).

"Eloides"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1990s. Place: Madrid and provinces, Spain.

Text at ?

Because his son has just obtained a license to drive a truck, Sanchez announces to his employee, Eloides, that he will no longer be needed. Incensed about losing his job, Eloides drops the bottle-filled case he was carrying. When Sanchez tells him he will deduct the cost of the broken bottles from his salary, Eloides strikes the truck with an iron bar until it catches fire. For that, he is arrested but released temporarily while the court debates the case. His wife, Lola, does not wish him back until he finds another job, so that he heads for his parents' house. Because of the likelihood of his being sent to jail, his friend, Roman, advises him to escape to Madrid and for that purpose loans him money. About to board a train, Eloides sees Sanchez' accountant sitting inside and pulls back in fear of being seen. Although suspecting that Roman plans to take his place in his wife's bed, Eloides leaves anyway. He arrives in Madrid on foot, but is unable to find a job. At an abandoned train station, he meets Luis, a vagrant who earns handouts by playing classical music on his violin and who harbors him at his lodging inside the station itself. At a handout place for vagrants, Eloides is upset on hearing a white man insult a black one and overturns a table over the former. With no place to go, he washes himself at a public fountain and scrounges for food in trash-bins even after a fellow vagrant has gone through it. Still hungry, he swallows communion wafers until a curate advances towards him with a sword taken from a statue of St Michael to hurry him out of the church. He returns to Luis' room to offer him two bottles of wine stolen from the church. While drinking with his friend, Eloides swallows too plentifully, becomes sick, and vomits. With Luis asleep, Eloides prepares to steal his coat and violin, but his friend wakes up in time and fights successfully over his possessions. However, Eloides takes away all his money, explaining that he intends to pay him back once he makes a profit in buying tickets for various events and selling them at a higher price. But when Elides lines up for soccer tickets, thugs beat him up and steal his money. He avenges himself on the ringleader by stabbing him to death. As a result, he is soon arrested and given a six-year jail sentence. Wearied at the thought of returning to a vagrant life so soon, he strangles his defense lawyer to death.

José Luis Alonso de Santos

[edit | edit source]"Bajarse al moro" (Going down to Marrakesh, more precisely Going down to the Moors, 1985) by José Luis Alonso de Santos (1942-?) features teenage drama and the drug culture.

In "Going down to the Moors", "Alonso de Santos presents a non-traditional family threatened, and eventually dismantled, by the intrusion of those who hypocritically hold traditional values. In this way, he exposes the socio-cultural myths of the 'traditional family' and, at the same time, critiques the socio-political reality of a newly-democratized Spain, still struggling with its Francoist past...The setting for Bajarse al Moro is Madrid and, more precisely, the centrally located, working-class neighborhood of Lavapies during the early 1980s. Here the protagonist Chusa, her cousin Jaimito, and her lover Alberto, share a humble apartment and existence. Quite obviously, the initial family encountered in this play is 'non-traditional' and, as a social unit, exists outside the bounds of socially acceptable practice...The element of discord in this extended kinship family is Alberto. Chusa, in her description of the apartment for the benefit of Elena, the young foundling she has taken under her wing, explains that certain areas of the apartment belong to Alberto and that he does not like his things disturbed, especially his billy club...Unlike the other members of this extended kinship family, Alberto is territorial about his 'space' and possessive of his things. He is not self-employed like the others but rather has a steady job within the bounds of 'acceptable society'...Therefore, while he may have been a true member of this extended kinship family at one time and continues to live communally with the other members, he no longer experiences their self-imposed marginality, life-style, or ideals...In direct contrast to the two 'free-spirits', Chusa and Jaimito, Elena is identified as a member of bourgeois society...Elena, like the uniformed Alberto, does not belong in this marginalized world...Chusa, acting as her older and street-wiser sister, wishes to include her in on a 'business' trip to Morocco to buy hashish. Importantly, Elena must first lose her virginity in order to be able to accommodate the smuggled hashish. Unbeknown to Chusa, her offering of her lover Alberto to Elena as a 'deflowerer' for business reasons has devastating effects. Not only does their coupling make Chusa jealous but, more importantly, it opens the door for a future marriage between the two traditionalists. The introduction of Elena into the kinship family by the kind-spirited Chusa is, therefore, the catalyst for the final undoing of the initial tripartite extended kinship family. When Alberto and Elena finally leave the Lavapies apartment as a couple, they unceremoniously sever all ties with Chusa and Jaimito. They effectively break up the non-traditional kinship family in order to form their own traditional family in a newly acquired home in the suburb of Mostoles. They have removed themselves far from the centrally located and working-class Lavapies both physically and ideologically. Nonetheless, their ideas about marriage would seem to be based on myth rather than the examples of their own families...Alberto's intrusive and caricaturesque mother, Dona Antonia, is the person of greatest influence on him and the strongest supporter of the traditional family model within the play. She obsessively and exaggeratedly criticizes her son and his roommates' drug use but at the same time is blind to her own drug addiction, as Chusa wisely points out...In her mind, therefore, her abuse of alcohol and her shoplifting are excusable while the use and selling of drugs by her son and his roommates are criminal and, indeed, sinful. The accusatory Dona Antonia is also a member of a born-again religious sect. The rhetoric that she extols on many occasions is the same as that of the Catholic church espoused by Franco...She calculatingly and successfully secures Elena as a future daughter-in-law...For this match-maker, the knowledge that Elena's mother is the owner of a profitable appliance store makes the girl the perfect bride-to-be for her son, overriding any possible qualms about her family background. It is not by coincidence or only for traditional family values, therefore, that Dona Antonia is so very eager to unite her son with Elena...The influence of Alberto's born again parents has overridden the ties he once shared with Jaimito and Chusa...Chusa, on being set free from jail, finds Jaimito alone and disheartened in the emptied apartment...Extraordinarily, the play ends with the potential formation of yet another alternative family: cousins with child" (Thompson, 1998 pp 812-817).

Santos’ “realistic use of dialogue distances his work from the theatrical tradition that placed emphasis on the rhetorical use of poetic language. Alonso de Santos instead creates characters that bring to mind the picaresque tradition” (Margenot, 1996 p 195). “Typically Alonso de Santos’s plays are bittersweet comedies. Their surface humour, creative use of contemporary slang, and intertextual references to filmic codes make them particularly appealing to a younger generation of theatre-goers” (Halsey and Zatlin, 1998 p 69).

"Going down to the Moors"

[edit | edit source]

Time: 1980. Place: Madrid, Spain.

Text at ?

Chusa invites Elena to live with her temporarily in an apartment shared with Jaimito and Alberto. Chusa explains that she intends going down to Marrakesh to pick up hashish and sell it at twenty times its value. Jaimito is at first against the idea of introducing Elena in their midst, but yields to Chusa’s decision. Suddenly, Alberto, a police officer, bursts in to say how he heard rumors that the police may soon investigate their apartment for drug possession, so that all three hide incriminating evidence. But it is a false alarm. Instead, Alberto’s alcoholic mother, Dona Antonia, arrives to complain about drug usage among the young and invites them to join a meeting of Charismatic Catholics. Elena would like to travel, but is queasy at the thought of Marrakesh because she is sure to become seasick on the way and leery about hiding the drug in her vaginal and anal tracts, all the more so because she is a virgin. Chusa proposes Alberto, her sometimes boyfriend, to handle the virgin problem, which Elena accepts, but their lovemaking is interrupted by Antonia, worried about her husband’s release from prison. The next day, Jaimito hangs around Elena, hoping she will choose him as a bed partner instead of Alberto, but she is uninterested. With Alberto and Elena locked in each other’s embraces, Jaimito and Chusa are stunned at seeing two thugs enter the apartment hunting for drugs. As Alberto and Elena rush out of the bedroom, Jaimito enters inside, pretending to look for the drugs. Instead, he comes back out with Alberto’s gun to scare the thieves. However, he accidently fires it in the air. The thugs flee, but Alberto is irate at his friend because of the danger they were all in when he fired the gun. While demonstrating its use, Alberto accidently shoots Jaimito in the arm, who is rushed to the hospital but recovers with just a minor wound. While Chusa heads for Marrakesh alone, Antonia is pleasantly surprised to hear of her husband’s reformation, now a proper and refined man agreeing to go with her at a church meeting. "In jail, he met a bank director condemned for embezzling millions," she explains to Elena. "He was the man who encouraged my husband to study and who taught classes there. Now he’s out, too, directing another bank, and has given my husband a nice position." Antonia is pleased with Elena and encourages her to marry Alberto. Elena is as willing to do so as she was to enter the drug culture. After Antonia leaves, Alberto informs Jaimito and Elena that Chusa was arrested in the train on the way back for possessing 300 g of hashish. To Jaimito’s disappointment, Alberto moves back to his parents’ house and refuses to help Chusa and thereby avoids risking to lose his position as a police officer. Chusa returns to find Jaimito alone. In the final report, she is accused of carrying only 50 g of hashish, because police officers kept 250 g for themselves. Elena arrives to say she has returned to her parents’ house until her marriage with Alberto and wants Chusa to pay back the loan that financed the trip, but Chusa refuses because she was cleaned out and so, to her mind, the loan has no longer any validity. An angry Elena insists on getting her money back until distracted by the arrival of Alberto and his mother, who, after taking away his possessions from the apartment, leave with her. Chusa thinks she is pregnant as a result of her relation with Alberto. To her surprise, Jaimito offers either to accept the role of father or help her get an abortion.