History of Western Theatre: Greeks to Elizabethans/Printable version

| This is the print version of History of Western Theatre: Greeks to Elizabethans You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

The current, editable version of this book is available in Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection, at

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/History_of_Western_Theatre:_Greeks_to_Elizabethans

Origins and Traditions

During the 5th century in the city of Athens, our first examples of public performance began to take place. Originally held in Eleutherae, was a temple dedicated to Dionysus, the Olympian Greek god of wine, the grape harvest, madness and ecstasy. On the southern slope of this temple, the earliest known formation of an agora developed which created the platform for all kinds of activities. All original dithyrambs and tragedies took place in this space along the hillside. Aside from performance art, other gatherings were held in the space including political, social, and religious gatherings, specifically the Dionysian festival, where competitions were held to judge the best tragedies and, from 487 B.C., comedies. The first winner in the tragedy genre was the 5th-century BC tragic poet and playwright Aeschylus of the Classical, Periclean age who also served as a hoplite in the Greco-Persian wars. It is this conflict that would heavily influence his later work The Persians: the only drama at the time to deal with relatively recent and contemporary events his audience would be familiar with.

Some would consider the agora as the center of the polis because of the various activities that frequently trafficked through the venue. However, the argument arises as to whether the first instance of "Greek Theatre" began here due to some defining qualities that are absent. There is little confirmation that the agora had an orchestra or whether they designated a particular space for an orchestra . If there was confirmation of an orchestra, then we can infer that the agora had designed a space for dancing and choral hymns. The presence of a "chorus" would also be an important factor in deciding whether "theatre" in the traditional sense took place there.

The Greek Festival

Anthesteria The oldest of Greek festivals, was a three day festival celebrating Dionysis, occurred during the middle of the month of Anthesterion (around the end of February). The first day was devoted to everyone including slaves, to join in festivities and join in wine drinking. The second day, participants dressed gaily and went around visiting friends, and participating in drinking competitions. The third day was a day of reverence, devoted to honoring the dead. Although this festival did not have dramatic elements, its structure influenced that of the Dionysia.

Dionysia The Dionysia was the first known dramatic festivals, Consisting of several smaller festivals held in each deme, or subdivision of Attica. The largest of these was the City Dionysia. The smaller Rural Dionysia festivals were normally in the month of Poseidon (around December). This festival's focus was centralized around the procession escorting a phallos brought in to encourage fertility within their autumn crops or of the earth in general, and slaves were allowed to attend the festivities.

Ticketing and admission fees in greek theatre were not introduced until the middle of the fifth century B.C.E.

City Dionysia The City Dionysia was a festival to celebrate the God Dionysus, who's cult name is Elutheria, meaning freedom. It is related with what is thought of as the home of the God, Eleutherai, which is located between Attica and Thebes. The festival would take place at the beginning of March/End of April and was kicked off by a procession. The procession on the first day, would go through the city, and the statue of Dionysus would be carried to the theater, which was built on the south slope of the Acropolis near the temple. The clothing of those in the procession would consist of bright colors and jewelry, and they would often wear masks. Those who were in the procession were the Ephebi, Canephori, and the human sacrifices. The Ephebi are men who carry shields and lances and escort the statue of the god. The Canephori are virgin women who carry baskets on their heads which contain things necessary for the sacrifices. The human sacrifices are provided by the state, individuals, or different population classes. Upon arrival to the theater, the sacrifices were made. At the end of the day, the procession (now lacking the human sacrifices) would follow its route back through the city, leaving the statue of Dionysis in the Orchestra.

The performances consisted of dithyrambs & narrative poems performed by choruses, as well as satyr plays, tragedies, and comedies. There were two types of competition. Dramatic competition, and choral competitions. Within the choral competitions, there were two separate ones. One for men, and one for boys. They were called cyclic choruses due to the circular formation in which they stood. There were five choruses of men and boys alike, composed of fifty members each. The choruses were provided by the tribes of Attica, making the competition a tribal one, and each chouragus (the leader) was from one of the ten tribes.

Architecture

The oldest theatrical area is at the Minoan Palaces at Phaistos. It consisted of stone risers for a standing audience of about 500. It also had a rectangular performing surface. Originally, the patrons of the Theatre of Dionysus had to stand to watch the performance. Around 489 B.C.E., temporary wooden seats were introduced. Permanent stone seats were not completed until some time around 330 B.C.E..

Typical audiences ranged for 17,000 to 21,000 and could seat upwards of 30,000 during festival times in what was called the Theatron. Known as 'the seeing place', it was usually built into the natural slope of a hilly terrain that sloped down into a flt bottomed area that was in or near a city. This shape was known as the Koilon which was a word for the actual flow of the whole of the theatre. The Koilon was split into what were called Diazoma, the upper and the lower, which were the wide horizontal walkways between the upper and lower areas of seating. The theatron was broken up into Kilmakes, the stairways of the theatron, and the Kerkis, the wedge shaped pieces of seating.

-The greek stage and all of it's parts.

The actual area for performance was split up into several different sections as well. The Orchestra, the Thymele, the Skene, and the Paradoi. The orchestra was known as 'the dancing place' and was a flat circular space at the bottom of the koilon. n the Theatre of Dionysus, the orchestra was created first, and was thought to be rectangular until it was rounded out in the forth century (which means that it was rectangular during the era in which the surviving Greek plays were written and performed). It was the area of the stage where the chorus was located and stayed. The chorus leader would stand upon the Thymele, an altar to Dionysus.

Yet a different view of the Greek Stage.

As drama developed into a major form and developments had to be made to just basic flat areas of stage, the Skene, which was roughly translated to "Tent", was at first (Around the fifth century) made up of wooden poles with a canvas roof that became stone in the fourth century. Started small and became grander as plays became grander. Also served as storage. It served as the back wall of the stage and had doors and sets within it as well as served as storage for the performance. Later on in time the name changes later to Scaenae which comes closer to our current 'scenes' and 'scenery'. It evolved in later time to a wooden structure with a flat roof with a stone core for onstage changing of costumes and masks while the chorus would sing. The Paradoi were one or two (Usually two) entrances for actors between the skene and the seats and is where the chorus entered. Located on either side of the Skene, they served as entrances and exits for the actors. Usually two gangplanks off either side of the orchestra that the chorus or actors would used for entrances. In addition to the Skene, the Paraskenion were side additions to the Skene in one of two story wings that could be ornamented with pillars or support a frieze. At some point in the theatre's development, the Logeion Proskenion was added as well. The name refers to "something set up before the skene" and was a raised platform in front of the skene.

An interesting addition that came along with the advent of Greek theatre are the Charonian steps. They were used as entrances into the action from the 'underworld' or ghostly apparitions of the departed.

Several devices were used as set pieces to forward the action in Greek theatre. The Machina, Ekkyklema, and the Periaktoi. A crane, the Machina, was used to lift the actors and sometimes certain props, such as a Pegasus, into the air. It was used to represent the gods or heroic characters or in comedy to make fun of such situations. TheEkkyklema was a roll out platform that was used for tableaus. It was most often used to display the dead bodies of actions that took place off stage and was rolled out from a center door in the skene. Finally, the Periaktoi were triangle pieces of scenery that allowed scene changes. Each side was a different piece of the scenery and could be turned in order to make a new backdrop with either side of all of the pieces.

The Deus Ex Machina was the term for the overuse of the Machina which was usually used to 'clean up' plots or contrived endings, usually by Euripides. The Gods would simply come down and solve the problems and then disappear again.

Plays

Sophocles

Ajax Written 440 BCE

Antigone Written 442 BCE

Electra Written 410 BCE

Oedipus at Colonus

Oedipus the King Philoctetes Written 409 BCE

The Trachiniae Written 430 BCE

Aeschyus:

Agamemnon Written 458 BCE

The Choephori Written 450 BCE

Eumenides Written 458 BCE

The Persians Written 472 BCE

Prometheus Bound Written 430 BCE

The Seven Against Thebes Written 467 BCE

The Suppliants Written ca. 463 BCE

Euripides:

Alcestis Written 438 BCE

Andromache Written 428-24 BCE

The Bacchantes Written 410 BC.

The Cyclops Written ca. 408 BCE

Electra Written 420-410 BCE

Hecuba Written 424 BCE

Helen Written 412 BCE

The Heracleidae Written ca. 429 BCE

Heracles Written 421-416 BCE

Hippolytus Written 428 BCE

Ion Written 414-412 BCE

Iphigenia At Aulis Written 410 BCE

Iphigenia in Tauris Written 414-412 BCE

Medea Written 431 BCE

Orestes Written 408 BCE

The Phoenissa Written 411-409 BCE

Rhesus Written 450 BCE

The Suppliants Written 422 BCE

The Trojan Women Written 415 BCE

Aristophanes

The Acharnians Written 425 BCE

The Birds Written 414 BCE

The Clouds Written 419 BCE

The Ecclesiazusae Written 390 BCE

The Frogs Written 405 BCE

The Knights Written 424 BCE

Peace Written 421 BCE

Plutus Written 380 BCE

The Thesmophoriazusae Written 411 BCE

The Wasps Written 422 BCE

Genres

In ancient Greek Theatre, there were only three genres of theatre: Comedy, Tragedy, and Satyr Plays.

Comedies were humorous plays with happy endings. Tragedies were morose plays with sad endings. Satyr plays were satirical farce of various myths and legends.

Tragedies and comedies were two distinct dramatic styles that were never intermingled.

Satyr plays were introduced later than the other two genres and were used in the Dionysian theatre festival as comic relief between tragedies. Satyr plays were regarded higher then comedies but lesser than tragedies.

Playwrights

Out of all the known Greek playwrights, the complete works of only four of them remain for us today. Out of these four, three are tragic playwrights, and one is a comedic playwright. The three tragic playwrights are Sophocles, Aeschyus, and Euripides. Sophocles was responsible for such titles as "Oedipus Rex" and "Antigone". Aeschyus was the author of "Agamemnon" and "The Persians", while Euripides was the creator of classics such as "Medea" and "The Trojan Women".

Complete lists of Plays

Sophocles

Ajax Written 440 BCE

Antigone Written 442 BCE

Electra Written 410 BCE

Oedipus at Colonus

Oedipus the King Philoctetes Written 409 BCE

The Trachiniae Written 430 BCE

Aeschyus:

Agamemnon Written 458 BCE

The Choephori Written 450 BCE

Eumenides Written 458 BCE

The Persians Written 472 BCE

Prometheus Bound Written 430 BCE

The Seven Against Thebes Written 467 BCE

The Suppliants Written ca. 463 BCE

Euripides:

Alcestis Written 438 BCE

Andromache Written 428-24 BCE

The Bacchantes Written 410 BC.

The Cyclops Written ca. 408 BCE

Electra Written 420-410 BCE

Hecuba Written 424 BCE

Helen Written 412 BCE

The Heracleidae Written ca. 429 BCE

Heracles Written 421-416 BCE

Hippolytus Written 428 BCE

Ion Written 414-412 BCE

Iphigenia At Aulis Written 410 BCE

Iphigenia in Tauris Written 414-412 BCE

Medea Written 431 BCE

Orestes Written 408 BCE

The Phoenissa Written 411-409 BCE

Rhesus Written 450 BCE

The Suppliants Written 422 BCE

The Trojan Women Written 415 BCE

Aristophanes

The Acharnians Written 425 BCE

The Birds Written 414 BCE

The Clouds Written 419 BCE

The Ecclesiazusae Written 390 BCE

The Frogs Written 405 BCE

The Knights Written 424 BCE

Peace Written 421 BCE

Plutus Written 380 BCE

The Thesmophoriazusae Written 411 BCE

The Wasps Written 422 BCE

Acting

Acting

History

In tragedy, Thespis introduced a single actor that interacted with the chorus, Aeschylus added a second actor, and Sophocles a third. Satyric drama followed the same rules tragedy did, so it was also limited to three actors. In comedy, Cratinus established the rule of having only three actors in a comedy, although, there could be more non-speaking supernumeraries. Playwrights themselves appeared as characters in their play, at first alone, and then with a professional actor. By the early fifth century however, this practice was not so popular.

Social Standing

The members of the Chorus were not considered actors, and neither were the people that played mute characters, or the characters with only a few lines to say. Only those who played parts that had a significant amount of dialogue were considered actors. Actors started out as unimportant followers to the playwrights. There was no demand for full-time performers. Being an actor was a part-time job. By the mid fifth-century, their names were recorded in competitions along with the playwrights, and by the fourth century, the actors were considered more important than the playwrights. Some playwrights even wrote scenes into their plays simply to show off the actor's ability.

Playwrights originally chose their own actors, and they would often use the same ones repeatedly. As the actor's status rose, the state began choosing the actors. They would then be given to the playwrights based on a lot. By doing this no writer had an unfair advantage. The other two actors were then selected jointly by the playwright and the lead. Actors were paid by the state, and if an actor was assigned to the Athenian festival and did not show up, he was fined by the state.

Only leading actors would compete for the prize which could be given for a performance in a non-winning play.

Acting Style

The voice was exercised and trained as much as an opera singer could today. Some actors had high vocal standards and achieved excellence, while other just yelled and ranted. Because actors were normally in masks, movement was simplified and broadened almost to the point of becoming symbolic. While there were two different acting styles for comedy and tragedy, the audience was able to pick out when an actor was not doing well with either.

In Comedy, voice technique was closer to general conversation. Movement and common place actions were exaggerated to the point of of the extreme and ridiculous, moving to the style of burlesque.

In Tragedy, voice technique needed to be “sonorous”, with a “loud and ringing intonation.” Articulation, rhythm and meter were also important. The movement style was more set and dignified. The style moved more towards idealization.

The acting was stylized and used masks and movements to tell the story rather than realism. Mask provided unique challenges to Greek actors in many ways. Resonance was an issue as the mask would obstruct the actor's use of his voice, creating internal resonance inside the mask, face, and head. Projection was a problem fixed by the koilon, which had naturally good acoustics, while the internal resonation was harnessed by actors to propel themselves into a more grandiose style of acting.

Due to the larger than life nature of Greek masks actors used a vocabulary of gesture, or cheironomia. Also translated into "Shadow Boxing" and "Pantomimic Movement," this process of using a set of particular gestures was employed to make the actors' bodies look proportional to their masks and also to bring out the emotions that were inherent within them. For example, lowering one's mask slightly could be considered a sign of contemplation while raising it could signal pride or a challenge.

Along with this physical vocabulary came Schemata, or "physical stances," that helped promote the mask to imitate the thoughts and feelings conveyed in it's facial expression.

"Silent Masks" were an interesting convention in acting technique. There is evidence in Greek tragedies of masked characters that are silent for extended periods of time or for certain scenes. This helped punctuate important moments that the playwright wanted to accentuate and also was a way in which death was portrayed. If a character was killed, the mask would often be put on a false dummy, freeing up the actor to play more roles.

Actors were judged above all by the beauty of vocal tone and the adaptation of speaking to mood and character. Therefore, acting style concentrated mostly on the voice with three types of delivery: speech, recitative, and song. Lines were recited more declamatory than realistic. There was no change in voice for difference in age or sex. It was more important to portray emotional tone.

Actor’s Guild

The Actor's Guild was created to protect theatre artists, and to raise their social status. The members were called Artists of Dionysus. Poets, actors, chorus-singers, trainers, and musicians belonged to guild. It is thought that the Guild may have originated with Sophocles’ literary club, though the two may not be connected. The group was definitely fully formed by the time of Aristotle. Because members participated in religious festivals, they received certain privileges, such as the ability to travel through “foreign and hostile states” to get to festivals and they were sometimes exempted from naval and military service (though not always).Later on, both of these privileges were made official by the Amphictyonic Council, also adding that the artists could not be arrested unless they owed a debt to a person or to the state. Another similar group is the Athenian Guild of Artists of Dionysus. They had a sacred enclosure and altar at Eleusis, where libations were offered to Demeter and Kore at time of Eleusinian mysteries.

Famous Actors

Aeschylus was associated with Cleander and Mynniscus, and Sophocles was associated with Cleidemides and Mynniscus. Callipides was considered arrogant, and Mynniscus considered his work to be of less dignity, and overly realistic. Nicostratus was well known for his delivery of long narrative speeches of messengers. A saying came about “To do a thing like Nicostratus”, meaning to do something right.

In the time of Demosthenes, there was Polus of Aegina, who taught elocution to Demosthenes, and at the age of seventy acted in eight tragedies in four days. Theodorus had a natural tone of delivery, and wouldn’t let subordinate actors appear before him on stage. He also thought that tragedy was much more difficult than comedy. Aristodemus and Neoptolemus were part of court of Phillip, and helped bring about peace of Philocrates. Thessalus and Athenodorus were famous rivals. Comic and Tragic acting were completely separated, and no actors attempted to do both. The comic actor Hermon's favorite joke was to knock heads of fellow actors with a stick. Parmenon was lauded for his skill in imitating grunt of a hog.

Contests between Actors

Originally, actors were not recognized, just poets and choregi, but later on best actor was rewarded as well as best poet. In the City Dionysia, about 446 B.C., the first official competition between tragic actors was held. In the fifth and fourth centuries, nothing is said about competitions between comedic actors in City Dionysia, it seems to have become a regular event in second century, though no one seems to know about the period in between. At Lenea, contests go as far back as 420 B.C. for tragic actors, comic actors as far as 289 B.C. for sure, maybe even further back.

The contests were limited to principal actors and protagonists, since they carried the play. They played not only the main role, but often several others. The other actors weren’t considered. Not only were contests for actors happening at the performance of new comedies and tragedies (alongside contests for poets and choregi), there were also contests for actors alone, where old plays were performed. In one form, each actor performed a different play, and the play was judged solely on the skill of the actor. These took place in Rural Dionysia, in townships of Attica, but not at the Athenian Festivals. In another form, each actor performed the same play, and most likely each actor performed only portions of the play. This kind of competition was most likely used by the state to choose which actor would perform the old play that went on before the new plays at festivals.

Selection of the Actors

Actors were not really needed until Aeschylus. They were at first chosen by the poets, and some actors became permanently associated with certain poets. The change in the selection process probably occurred in the mid-fifth century, when acting contests first started, and actors were officially recognized in festivals. Three protagonists were selected by the archon. The method of selection is unclear, though it was probably a small contest. Subordinate actors were not chosen by state, though the protagonist could provide his own deuteragonist and tritagonist. The protagonists were assigned to poets by lot. The three poets competing would draw to ascertain order of choice, then each would choose his actor. Each protagonist would act in all three tragedies of the poet he’s given to. Whichever actor won was able to compete in the next years festival without having to be chosen by the archon. By the middle of the fourth century, all actors were divided equally among the poets (since success of play depended on talent of actor, not so much on the poet). Each poet would have all three actors act in one of his three plays, so each actor would have acted under each poet.

Comedy seems to have been run the same way, though each poet only submitted one play, so the last change was not needed. Sometimes an actor would act in two plays, though not often.

Adaptations

Adaptations of Classic Tragedy plays by actors were encouraged by government. When it was found that actors were tampering with the text, the orator Lycurgus tried to put a stop to it by passing a law that stated that actors must perform the text as written. He also had public copies made of the works of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides that were deposited in the state archives.

(need to cite The Attic Theatre)

More Acting Stuffs

[edit | edit source]Acting as an etotic[check spelling] artform was developing in Athens alongside other more traditional artforms such as painting, sculpture, art in its entirety, etc. The physical representations of Greek Actors were directly influenced by the likenesses taken from Greek art. A modern example of this would be contemporary actors developing their character traits from photographs, other live performances, or film. The Greeks drew from what they were exposed to, as said before, sculptures, figures from ceramic art, paintings. The artistic fundamentals of shape, form, the line defined the actor and his/her body in the three-dimensional sense of the stage. This was the only available media a Greek actor could utilize. Likewise, fine artists took inspiration from technical stage design. Some of the creative inventions that became of Greek theatre became useful to further motivate fellow artists. (need to cite Pollitt-Greek Sense of Theatre)

Walton, J. M. (1984). The Greek sense of theatre: Tragedy reviewed. London: Methuen.

Haigh, Arthur Elam, and Sir Arthur Wallace Pickard-Cambridge. The Attic theatre. The Clarendon press, 1907. Print.

Chorus

Chorus

[edit | edit source]The Chorus is a group of actors that together speak, sing, and dance in one body. The Chorus is part ritual part thematic device that play a much larger role in Greek Tragedy than in the other genres. One of the primary functions of the chorus is to provide atmosphere and, in some ways, underscore the tragic action. When the hero is treading upon major conflict or leading us into the rising action of the plot, the chorus, in a way, are heralders of inevitable disaster and instill a sense of fear or suspense in the audience. In some ways the Chorus can represent the audience's ideal response to the play. Nietzsche feels that the Chorus, and it's chants and songs, helped the audience better connect with the character, revealing the essence of the tragedy.

In early tragedies the Chorus was dominant. They could be used to fill time when the one main actor went off-stage to change roles or for scene changes. The Chorus could sometimes have as much as half the lines in a single show. In Aeschylus' plays, the Chorus could even serve as the protagonist or antagonist.

There is a disagreement among historians as to the actual size of the standard Chorus. Some say it started at 50, then changed to 12 with Aeschylus, then to 15 with Sophocles and Euripides. Those who say the Chorus was always as small as 12 or 15, believe that the 50 Chorus members were divided amongst the four plays with which the author was competing. This helped reduce the cost of a production. Sometimes the Chorus could be as small as three people, or there could be a second Chorus.

The Chorus usually entered with a stately march, sometimes singing. Although, they could enter from multiple directions. Onstage formation would consist of three to five member lines. While the Chorus sung and danced in unison, there could be two groups that took turns. They would exchange dialogue with the characters, sometimes as individuals. When it came to acting, the members of the Chorus would respond appropriately to the situation.

Old Comedy Chorus had 24 members and had approximately two semi-choruses. One of each gender. Chorus in comedies could have mixed genders and were more active. In dramatic form, The Chorus did not enter until after the prologue and stayed onstage for the entirety of the show.

Training of a Chorus was probably spread over the 11 months the playwright had with the Chorus before the performance. At first, it was the author who choreographed the Chorus, but as time went on this job was taken over by professionals. Some say this training was similar to that of athletes.

Costumes

Traditionally in Greek theatre Comedic performers wore the everyday garments of the Greeks. This included a body stocking, an under tunic, a draped woolen garment called a chiton, and possibly a form of draped outerwear called a himation.

The body stocking was used to insert padding materials to exaggerate the stomach and the rump, known as the progastrida / progastreda. It also created a space for the female breast plates called prosterniad / prosterneda. These were used by male actor portraying a female character since women were not generally allowed to act. This also could be a place where a comedic leather phallus could be worn.

There were two large variations of the chiton that were popular in Greek theatre, the Doric and the Ionic. The Doric chiton (or also referred to as peplos) was six feet wide and two and a half feet longer than the shoulder height of the wearer. This chiton was wrapped once around the figure with excess material folded over the top and doubly covering the bodice. The cloth was tied around the waist and then pinned at the shoulders (sometimes with brooches) leaving the arms bare. The Ionic chiton later replaced the Doric, and has the wrapping style primarily associated with ancient Greek theater. It was a much wider garment but fitted to the exact height of the wearer so there was no excess fabric at the neck, thus creating more opportunity for displaying jewelry. During the Hellenistic period, with the growth of trade and mercantilism, linen and Asian silks eventually replaced wool as the fabric of choice. Variations on the Ionic chiton and accessories also existed. For example, it was acceptable for a chiton to be clasped over the left shoulder instead of both.

There were also extremely popular garments which were wrapped around one or both shoulders called Himations, which also became an important costume piece. Most knowledge of the grecian style of dress comes from remnants of sculptures and pottery. Due to discoloration and a loss of paint pigments the garments appear to be white. A common misconception of Greek clothing is that they were lacking in color, but in actuality Greek clothing took on various colors, sizes, and levels of ornateness.They were dyed many colors, and even if the fabrics were plain white they often had borders. Expensive, bold threads, intricate borders, and tightly woven fabrics such as fine linen and silk showed high status on as well as off of the stage. The length of the chiton was also a good representation of status. Regardless of the actors age, a knee-length tunic would depict a young man, a long tunic would represent an old man, and an extremely short tunic would be insignia of a soldier. Women, regardless of status, always wore full length chitons on stage.

The padding and phallus were conventions of comedic costuming that coincided with the era of Old Comedy, which lasted roughly a century. With the advent of the era of New Comedy, came the increasing realism of costumes. The phallus and padding were lost in favor of more pedestrian, normal shapes, allowing more freedom of movement for the actors.

Another theatrical costume piece was a heeled wooden shoe, kothornoi / cothurnus / cothornous, or sometimes called a buskin. This platformed shoe gave actors on stage more height and better visibility to their audience as well as offsetting the grandeur of the masks they wore. The thick shoe was later replaced by Soccus, thin soled leather shoe, in keeping with the general move towards realism in that new era.

Later, Tragic costuming pushed in opposition of the short-statured and padded protrusions of the comedic figures. Tragic figures were known for height and esteem. On stage, this effect was achieved by wearing high kothornoi and elongating the forehead of the mask. Height of the characters was directly proportional to the importance which eventually lead tragedy to be the more respected form of drama. As far as dress is concerned, both tragic and comedic actors bore the traditional greek dress of chitons, tunics, and himations. Since tragic figures could not rely on height alone to denotate importance, more attention to fine fabrics an ornate detailing was put into distinguishing the gods and upper-class from more common citizens. It was not uncommon, however, to have a hero enter dressed in rags and later in fine clothes to show status progression.

Tragic costumes were strictly formal in nature and no more meant to depict real costumes than the set was meant to depict a real place. So there was an accepted suspension of disbelief in the visual aspects of Greek Tragedy. The masks and formal wear of the tragic theater were meant to depersonalize the actors.

The chitons of tragic costumes were most likely all purpose garments, designed so that simple alterations could represent a whole variety of characters. This variable design was very important for the actors of the age because, as with modern stock companies, actors were expected to provide their own wardrobe. If, as an actor, you owned a few multipurpose costume garments they would be precious property and essential tools in your acting arsenal.

There was a definite level of uniformity to all tragic costuming. Color symbolism, in addition to height distinction, was heavily employed. Royalty was in purple, priests wore white, and young maids in yellow. Thusly an early tendency toward stock characters was fostered. Death was depicted as an actor with black wings and a large sword. Specific hair colors, attached to masks, held symbolic value. Golden hair was called for on specific characters, white for the elderly, and cut short or "cropped" for slaves and characters in mourning. Foreigners may have been distinguished by lavish, more exotic garb. Any character that was supposedly from an oriental nation likely wore uniform non-distinct Eastern dress.

Distinctions of rank or function were indicated by carry-on props. Homer and Aristophanes show us motifs of tragic kings invariably carrying scepters with a single eagle carved in the top, and warriors with double throwing spears. Many more play writes call for heralds with wreaths and travelers with wide-brimmed hats.

Costuming Episode of Sherman and Dr. P.Scottie

Come join us as the daring duo of Sherman and Dr. P.Scottie once again travel time in search of fun facts and adventures. In this Episode Sherman and P.Scottie find themselves transported thousands of years onto the stage of a Greek Festival. Mistaking it for a masquerade they begin to dance with actors, when suddenly the locals turn on them. P.Scottie realizes that they stick out like a sore thumb in their futuristic garb. So they set out to find some ancient Greek wear to assimilate themselves into the culture for further investigastions.

Problems arise when the two dress themselves but have no idea the social significance of ancient Greek garments. They try on slave-wear, soldier-garb, and they even try on womens clothes before they realize what to wear to be hifalutin.

Masks

Greek Masks were usually made from wood, cloth, cork, hardened linen or leather and often included human and animal hair as decorative accents. Two small holes for the eyes and tiny holes for the mouth and ears were also included in the mask so that the actor could hear and be heard by the audience and his fellow performers. The reason there are no original Greek masks to study is because they were created out of biodegradable materials and were often sacrificed to the god Dionysus after performances. There is, however, evidence of the masks from paintings on Grecian urns and ceramic wear.

Comic mask were grotesque distortions and parodies of the normal human face. The parts of the face that would most often be distorted were the mouth and eyes, agape or bulging out respectively, to increase the humor or comedic aspects of plays and characters. Comic masks also included representations of gods in human form or anthropomorphic disguise. They usually involved gender bending, males wearing female masks, and highlighted the differences between the sexes for increased comedic effect. These were the masks of the Old Comedic Period in Greece which lasted roughly a century.

The New Comedic Period started around the late 4th century and lasted up until the 2nd Century BC. Masks of this period were starkly more realistic and shifted drastically from the over the top, gender twisted portraits of the earlier comedies. Instead of accentuating gender, masks were instead made to punctuate contrasting stereotypes, such as the stern father and the lovelorn son. The visual emotional differences and contrasts in masks were supposed to create comedy rather than relying on the abuse of gender relationships.

Tragic masks generally had wide open mouths, a sign of lamentation, suffering, or anguish. They were, more often than not, more realistic than comic masks of either period. Tragic masks made the actors wearing them look taller by enlarging the length of the forehead, this being due to the trend in Greek theatre that the taller the character was the more important they were to the story. Tragic figures were almost always taller than figures in comedies as it was the more respected form of theatre during that time.

Special masks were often made for characters that needed to be distinct. The most prominent example being the mask for Oedipus in Oedipus the King. A mask would have had to be specially made to show the unique changes that the character goes through during the course of the play, including gouging his own eyes out.

The reasons that Greeks used masks were many, though some were more important than others. First and foremost, the use of masks was a symbol of worship of the god Dionysus, as they were predominantly seen and used during festivals celebrating the same god. Secondly, the masks provided increased visibility to all the audience members in the koilon. Coupled with the natural acoustics of the outdoor theatre this provided and equally profound performance for all the people in the audience, back rows included. It also gave actors the ability to play multiple characters in a single performance, and expanded the ability of male actors to play female roles, due to the fact that during this time females could only participate in a limited extent in the chorus.

-

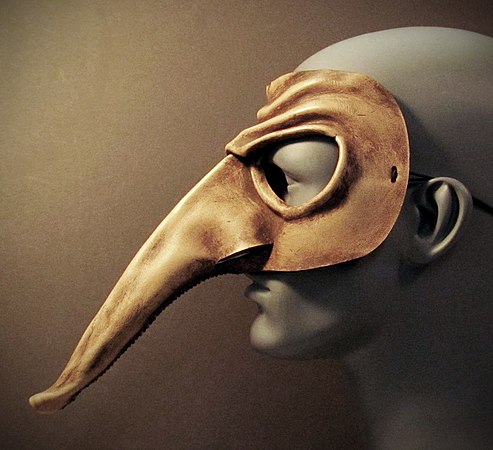

A Greek theater mask.

-

Roman terracotta mask of a Satyr.

-

A Zanni mask used in the Itallian Commedia dell'arte.

-

Harlequin, a stock role in Commedia dell'arte, wearing a mask.

Scenery

The skene was the main form of scenery in ancient Greek theatre.

The skene was a large rectangular building behind the orchestra actors could use for costume changes, like a backstage. However, it could also represent the play's location such as a palace or a house. The building was sometimes painted, as well, like a backdrop. Also, there was roof access behind the skene so characters playing gods or watchmen could enter there. In the beginning, the skene was a tent or hut, put up only for religious festivals and then taken down. It was not until later on that it became a permanent structure.

With the creation of the stage, there was a large movable facade that could be painted as a backdrop. It was always painted the same according to the genre of the play. Tragedy: an official building, comedy: rural buildings, satyric drama: a cave entrance.

Depending on where the actors entered from could have implied scenery offstage. These places for entrances and exits were side doors beside the retaining walls of the auditorium called paradoi. The right hand door meant the character was arriving from the city and the left hand door meant he was arriving from a far away place.

Decorative scenery was not built as substantial architecture until Lycurgus in the fifth century B.C. Before then, wooden structures served as skeleton framework while there was movable scenery in front. At first, the screens that functioned as scenery were skins that were basically backdrops without pictures rather than actual backdrops that we would think of today. The modern idea of backdrops, or skenographia, started around the time of Sophocles (and is often credited with their invention). Scaena ductilis, or proskenion, is similar to the modern idea of a set. The entire set wasting was painted on screens that were put on the wooden skeleton structures mentioned above.

To be edited: “No two Ancient Greek theatres were exactly alike, and when the history of each is considered one discovers that the various forms, which reduced to simplest terms constitute for us the normal type, were the result of gradual changes and repeated adjustments.” Priene, Turkey has best preserved logeion (“speaking place”)

Orchestra: 2 approaches (“hardened earth”)

- eisoidi: entrance

- parados : side entrance

episkenion: 2nd story of stage thyromata: folding doors (typically on episkenion)

Props

The Deux Ex Machina

In many Greek plays a crane, called the Machina, was used to elevate the actors for flying in roles of Gods or Heroes.

Horses were used for chariots and to represent Pegasus. They were usually adorned with elaborate costumes that could make them unruly to control. In at least one play, a pegasus was called for but with the use of the Machina, a dummy was used.

Torches were used to represent the night.

General Fact stage props - Props not used for simulating reality... Used to create dramatic emphasisActors used props to suggest further character development, beyond masks and costumes. A walking stick could suggest old age or spears could suggest military. Skeupoios, or props-makers would provide the actors with the props, and many of the props-makers made their living off this practice.

Special Effects

Mechanai, or machines were devices that were used to lift actors, allowing them to appear behind the scenery. The mêchanê were similar to cranes that we have today. This was a common method to portray the Greek Gods. An Ekkyklema, or wheeled out platform would be brought onto the playing area to show scenes that took place beyond the view of the audience. Many times, they were brought out to show the results of violent acts, especially deaths (as those were never played out on the stage.

Social Context

Perecles introduced the idea of a "theoric fund" to pay for poor people to attend the theatre, thereby making theatre open to all classes. this happened around 450 B.C.E.

The Theoric Fund was the name for the treasury that handled the financial dues for all the festivals, sacrifices and public entertainment of all kinds, as well as the distribution of money to those who could not afford it in terms of the generosity of the state. It was established so that the lower class of Athens could afford to go to the public festivals of worship. Most of the money came from the public treasury though a select few individuals would also donate and take some of the burden of funding upon themselves.

Originally there was no charge for the festivals and the audience would often degenerate into fights due to the lack of seating. Because these outbreaks became so commonplace, an admission fee was instituted, to cut down on the violence. This, however, did prevent a portion of the population from attending the festivals.

The Theoric fund was established soon after. A citizen would receive something akin to a voucher, one for each day of the three-day festival of Dionysus.

in the late forth century B.C.E. the cost of admission was standardized to a cost of two obols.

The Story of Greek Theatre

[Note: the purpose of this story is to imaginatively connect into a narrative the many facts we have provided in the section on the Greeks. This should not be read as history, but as historical fiction. Our hope is that students reading it will more easily remember some of the details of Ancient Greek Theatre.]

Dionysus lifted his scrawny, baby-sized arm and declared, "Worship me here. In the clearing. I like it." And so the people did. There were only a small number of followers in the beginning. Maybe 12. During this period, a local could see the small cluster of dionites roaming through the hills with a chubby dwarf clinging to their backs. In a time before performance, the dionites worshiped the little Dionysus on street corners and nearby farms where there were lots of cattle. They were never quite audience-specific, but immensely grateful for anyone or thing that could shed a moment of its time for some praise. Their worshiping usually consisted of singing, dancing, and a sucking on the flesh of the little dwarf god, Dionysus, for his pores secreted the finest wine. Cast parties were rampant, but not without an adequate pigeage of the dwarf. This, of course, could only be accomplished by putting Dionysus in a knee high wooden barrel, where the dionites would hike up their robes and stomp him in order to cull massive quantities of wine. As attendees began to gain in size, street corners and fenced off cattle-yards would not suffice any longer. The little Dionysus and his/her 12 apostles formed a production company, Agora & Friends Stage Co. The little Dionysus entitled himself as artistic director and the rest of the company members he called the chorus. They all agreed unanimously, like they usually do, and at the same time. For their first performance the AFSC chose a nice flat clearing for their large audience turnout.

The chorus roamed the polis to find 28 other members that were identical in likeness, sexuality, and orientation in order to expand the experience of their worship that was already quite erect. The original chorus members knew that this would please their little Dionysus greatly for he loves to be worshiped. "Worship me a lot. And give me lots of standing ovations and cast parties were the wine shall be milked from my flesh all night long. This is what I want and what you need to have good theater." said the little Dionysus.

Once the chorus reached a whopping 40 identical members, they were inseparable. They all grew to be very close friends who always walked together and gossiped heavily, frantically vocalizing on every bit of human tension they crossed in public. They were quite atmospheric. The chorus were notorious for holing up in city alley-ways awaiting passerby's and would often deploy random acts of pillage and evil, in short R.A.P.E. These raucous affairs were performed solely to accumulate patronage points with the chubby dwarf god Dionysus, whom usually attributed these massive celebrations with a monologue of some kind. The field performances lasted for quite sometime. Audience members began to dwindle and the hecklers seemed to attended out of sport largely because no one took the ceremonies seriously.

The dionites packed up their little chubby messiah and fled to the forests where they could find safety and peace for a clandestine production meeting. "Children! We must leave the plains. They are not working for us. I don't know why. Decibilus, you are the sound designer. What is wrong with the sound, my child?" asked little Dionysus.

"Well, my lord. Sound is strange. But it is good. We need sound. And we want the audience to want the sound as much as we do." said Decibilus.

"This is right young Decibilus! We want them to hear what we are saying about me. How do we achieve this?" asked Dionysus.

"Well, you see my lord. I don't know because sound design is kind of a new thing for me. I'd rather just suck the wine from your flesh."

"Of course you would! But no wine for you until we fix the sound."

"We could move to a hillside." said House Managus Maximus.

"Will this work Decilibus? If we change the seating area to that of a hillside?" asked Dionysus.

"Well, uh. Yeah. Sure. Why not. What do you think Acousticus?"

"Sounds good to me." said Acousticus.

And so they fled to the southern hillside of the acropolis and prepared for worship. At the base of the hill, Tekk Directus began constructing a large square platform to be built for the chorus to stand-on. Scenus Designus took much offense to Tekk's aesthetic taste and demanded him to knock off the edges and form a circle. Tekk Directus refused to do any modification unless Scenus Designus would agree to make a child with him on top of his platform. Scenus agreed and 9 months later, Orchestrus was born.

Orchestrus was a wonderful dancer. She loved to join in with the members of the chorus for musical numbers and songs. When cast parties came along, however, Orchestrus was never invited because she got a little too drunk at her first cast party. Orchestrus insisted on singing karaoke and giving lap dances to all the actors in the company. One actor in particular that she fancied was Mattus Broderikus. Mattus Broderikus was the best dramatic actor around. He found Orchestrus' antics captivating. The next day, he asked her out and she gladly accepted. Unfortunately, the relationship only lasted a few months before Mattus found the woman of his dreams: Sarah Parkus. The break-up devastated Orchestrus, and she swore to never trust another actor again. A few months later, she realized she was pregnant. Orchestrus gave birth to a little boy, named Skennus, after his grandparents.

Now, Orchestrus demanded child support since Skennus was after all the son of Mattus, but as an actor Mattus was dirt poor and had to find other ways to help out with the child. So, instead of trying to supply funds he didn't have, Mattus agreed to look after the infant several days a week by taking him to work at the theater. But from birth the child was a hell raiser and constantly making all kinds of disrupting noises. After a while Mattus' fellow actors decided the child was too much of a distraction and that something needed to be done. Since Mattus could not go back on his word to watch Skennus, and since leaving the kid on a random street corner was frowned upon, he decided to enlist the help of Shoppicus Constructus to build a small hut like building where the child could be kept out of sight. But as every good parent knows, you must check in on your child. So every time someone needed to change masks or costumes they went into the shack to check on the child and make sure it was okay.

Italian Renaissance comedies

Main figures in Italian Renaissance comedy are Ruzante (Angelo Beolco, 1502-1542) and Niccolo Machiavelli (1469-1527). Ruzante wrote "La Fiorina" (Fiorina, 1531) and "La Piovana" (Rainwater, 1532) and Machiavelli "Mandragola" (The mandrake, 1518).

"Fiorina". Time: 1530s. Place: Italy.

"Rainwater". Time: 1530s. Place: Italy.

"The mandrake". Time: 1510s. Place: Florence, Italy.

Callimacus has an eye on Nicia's wife. He pretends to be a doctor with a potion containing mandrake, a plant-substance able to make her fertile, provided a man copulates with her, though he dies from it. Nicia first protests but then agrees to kidnap a passing stranger for the deed. To convince the religious-minded Lucretia, Nicia's wife, to cooperate, Ligurio, Callimacus' parasite friend, proposes to use her confessor, Timoteo. To sound the priest's morals, Ligurio first invents a tale whereby the wife of Nicia's nephew is said to be pregnant in a convent and must be made to swallow with his help a potion to abort the foetus, in exchange for money. Timoteo hesitates but then agrees. He is then told the tale Nicia already heard, and agrees to participate in it. To Lucrecia's objections, Timoteo counters that this is a case of possible versus certain good. Whether the copulator dies is uncertain, whereas the goodness of a birth offered to the Lord is certain. Ligurio, Timoteo, Nicia, and Callimacus' servant grab Callimacus disguised as a musician and force him inside Nicia's house, where he is conveyed in Lucretia's bed. The next day, Nicia explains to Ligurio the success of the operation, how he first examined Callimacus' body to detect any type of disease, and, satisfied on this and other matters, is now joyfully certain to be a father. To Callimacus he is so thankful that he hands over to him a key to one of his rooms whereby he can enter as he pleases.

Elizabethan comedies

As in tragedy, Shakespeare was dominant in comedies, with "A Midsummer night's dream" (1595), "As you like it" (1599), and "Twelfth night" (1601).

"A Midsummer night's dream" text at http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/A_Midsummer_Night%27s_Dream

"As you like it" text at http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/As_You_Like_It

"Twelfth night" text at http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Twelfth_Night

In addition to Shakespeare, main playwrights of Elizabethan comedies are Ben Jonson (1572-1637) and Thomas Dekker (1572-1632).

Jonson's most famous comedy in the Elizabethan period is "Every man in his humour" (1598), whose pace is both rollicking and slow at different times. In this story, Knowell seeks to prevent his son, Edward, from falling into bad company, notably with Wellbred, half-brother of Downright. Edward plants a spy, his servant, Brainworm, to find out his father's intentions and to distract him. Knowell greets a country bumpkin, Stephen, who, in a rash humor, picks a quarrel with Brainworm, who later, disguised as a poor soldier, cheats him by selling at a high price a cheap sword. Bobadil, the Elizabethan version of the Roman Miles Gloriolosus, the braggart soldier, receives the visit of Matthew, a city bumpkin, who tells him he has been threatened to be beaten by the hot-tempered Stephen. Bobadil is outraged and promises to help kill his foe by teaching him the art of duelling with a sword. The merchant, Kitely, always worried about being a cuckold, hesitates even to leave his house for a few minutes, especially as a result of his lodger, Wellbred: "He makes my house here common, as a mart,/A theater, a public spectacle/For giddy humor and diseased riot-," and asks the help of his servant, Cash, ineffective in this regard. The irascible Bobadil quarrels with the equally irascible but more valiant Downright, separated at first by Kitely, but later Bobadil meets Downright again and, forced to fight, pretends he has received a government summons not to, and is shamed in front of his friends. Cob, the water-carrier, is another man suspecting his wife of cuckolding him. Kitely, thinking his wife has a lewd meeting at Cob's house, accuses her of cuckolding him, at which time Cob, suspecting his wife as a bawd (procurer), beats her. Downright objects to visits by Wellbred and his friends to Dame Kitely and Bridget, especially with respect to Matthew's poetical verses. But Wellbred, as Bridget's brother-in-law, encourages her to receive the attention of his friend, Edward Knowell. Knowell senior discovers too late his son's marriage. Brainworm, taking Stephen's cloak carelessly left on the street, is challenged to give it back but does not, until faced with Judge Clement, whose merry humor resolves all quarrels.

"Every man in his humour" text at http://www.archive.org/details/everymaninhishu00dixogoog

Dekker's most famous comedy in the Elizabethan period is "The shoemakers' holiday" (1599).