How Wikipedia Works/Chapter 2

- The World Gets a Free Encyclopedia

The hopeful dreams from the early days of Wikipedia have become reality. There is a free, online encyclopedia, and in Chapter 1, What's in Wikipedia?, you reviewed its content. But what led to Wikipedia's creation, and what is the philosophy behind the site?

In Serendipities, leading Italian academic and intellectual Umberto Eco closed his first essay with this thought:

- After all, the cultivated person's first duty is to be always prepared to rewrite the encyclopedia.[1]

In 1994, when Eco lectured to the University of Bologna on "The Force of Falsity," he naturally did not mean this statement literally. For him, the encyclopedia is metaphorical; a revision of beliefs is a sign of a civilization that can question itself, and fresh views and discoveries, such as a scientific advance or the exposure of a forgery, prompt new summaries of knowledge. But Wikipedia has allowed this metaphor to spring to life: Daily, thousands of people "rewrite the encyclopedia," and no one checks to see whether these editors have the appropriate degrees or credentials or are even dressed for the occasion.

Wikipedia combines the ideas of the encyclopedia, the wiki website, and free and open content to define how a free encyclopedia can be built by everyone. In this chapter, we'll explore these three ideas and how they have evolved, discuss the motivation behind the project and its early history, and examine the drawbacks to Wikipedia's method by discussing some common criticisms of the site, centered around a few case studies. In the last chapter of this book, we'll return to more recent history and the current organizational side of Wikipedia. In the meantime, as you read and edit articles and participate in community discussions, knowing Wikipedia's philosophical background and influences is key to understanding how it works.

Wikipedia's Mission

[edit | edit source]What is Wikipedia's role? In the 21st century, distributing information is easier than ever before. A megabyte of data—equivalent to the text of a large book—can be sent to mobile phones in most parts of the world for less than one cent. The Internet's infrastructure is increasingly available to the world's population, and broadcasters and publishers are becoming less-necessary intermediaries.

What has been missing is the freely available online information itself. The Web has plenty of other content: news, opinion, virtual shopping, and social networking. What the Web has lacked are hard facts, and quality factual material can change lives.

This is where Wikipedia comes in. Its mission is to make the whole world's information available in all languages. Until now, this has not been possible: Large reference libraries are not spread evenly around the planet. If you believe that good and balanced information is something that everyone needs, you can understand why a comprehensive, neutral online encyclopedia is important. And if you believe this information is a tool that everyone should be able to use in their daily work, you can see why a free, accessible encyclopedia is essential. Having quick, easy, everyday access to facts and reference materials matters now and is not merely a science-fiction concept like in Isaac Asimov's Encyclopedia Galactica or Douglas Adams's handheld Hitchhiker's Guide.

- What Wikipedia Does: "Imagine a world in which every single person on the planet is given free access to the sum of all human knowledge. That's what we're doing." —Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales, from an often-quoted 2004 interview on Slashdot

- Further Reading

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serendipities Wikipedia's article on the Umberto Eco book cited at the beginning of this chapter

http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Jimmy_Wales The Slashdot quote and other Jimmy Wales sayings

Wikipedia's Roots

[edit | edit source]Wikipedia was founded in 2001, but the critical ideas and developments that helped shape the site were developed long before that. These ideas are listed below in chronological order. They show a quickening pace, especially after 1990 when the World Wide Web became a concrete proposal. Throughout the 1990s, technology progressed. New ways of thinking about tools emerged, and thoughtful and innovative developments combined to affect the content and implications of computer technology. These developments have produced ideas that are shaping the world. Wikipedia is part of a long tradition that predates the Internet, however, and some much older ideas feed into Wikipedia's culture—not least of which is the revolutionary concept of the encyclopedia.

Ancient Greece to Today: Encyclopedias

[edit | edit source]What is an encyclopedia? To most people, an encyclopedia is a large book or multivolume work. Comprised of a comprehensive collection of short articles, an encyclopedia divides an area of knowledge into separate topics. Encyclopedias are reference works, designed to orient new readers, summarize details that might have previously been spread over many publications, and provide a summary of available information in comprehensible terms. A good encyclopedia can answer many questions, without replacing the sources from which it was constructed.

Encyclopedias are examples of tertiary sources. They are neither primary sources, such as historical documents, nor are they secondary sources, such as textbooks, which usually discuss, report on, or interpret primary sources. Instead, an encyclopedia's compilers have gathered and summarized available secondary sources (often noting primary sources as well) to report on a field of knowledge and current thinking at that particular time.

The encyclopedia has venerable origins. Early examples exist in manuscript form in cultures around the world, and bound encyclopedias have been around almost as long as there have been books at all. Pliny's enormous Historia naturalis, written in 77 AD, is often cited as one of the first encyclopedias; this work was influential for at least 1,500 years. Some of the other very first encyclopedias were written in Chinese (the now-lost Huang Ian, published around 220 AD) and Arabic (the 10-volume Kitāb 'Uyūn al-Akhbār, or Adab al-Kitāb, compiled around 880 AD). Throughout the medieval era in Europe, other encyclopedic works were developed, many written in Latin and based around philosophical and religious ideas.

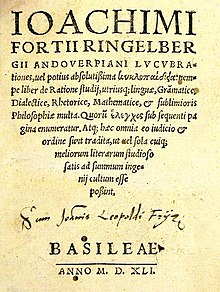

The word encyclopedia was not used to describe these works until much later, however. So where did this word originate? Wikipedia itself provides this explanation, crediting the 16th-century scholar Joachim Sterck van Ringelbergh (Figure 2.1, “Title page from Lucubrationes vel potius absolutissima kyklopaideia, 1541”):

- The word encyclopedia comes from the Classical Greek "ὲγкύкλια παιδεία" (pronounced "enkyklia paideia"), literally, a "[well-]rounded education," meaning "a general knowledge." Though the notion of a compendium of knowledge dates back thousands of years, the term was first used in 1541 in the title of a book by Joachimus Fortius Ringelbergius, Lucubrationes vel potius absolutissima kyklopaideia (Basel, 1541). The word encyclopaedia was first used as a noun by the encyclopedist Pavao Skalic in the title of his book, Encyclopaedia seu orbis disciplinarum tam sacrarum quam prophanarum epistemon (Encyclopaedia, or Knowledge of the World of Disciplines, Basel, 1559). (From w:Encyclopedia, April 2007)

The earliest encyclopedias compiled knowledge about the entire world and were meant to be read straight through as a complete education.[2] This notion eventually evolved into the more modern concept of an encyclopedia as a reference work, more akin to the concept of a dictionary in which words are defined for easy consultation. (Encyclopedic dictionaries, a hybrid form, have existed since at least the second century AD.) An encyclopedia in the contemporary sense may illustrate objects, map places, contain articles about history, geography, science, and biography, and cover the spectrum of factual knowledge.

In the modern age, traditional encyclopedias have worked hard to balance the topics important to their audience with limited space and editorial capacity. Generalist encyclopedias aim to be universal in scope, while being compact enough to be fully updated every few decades and to fit on a bookshelf. Specialist encyclopedias can fill a similar amount of space for one field or subfield. A general children's encyclopedia such as World Book is written with a different format and goals than a scientific encyclopedia, but both provide clear introductions to topics. This formula has been a successful one, providing publishers with high sales continuing from the 18th century to today.

Today thousands of specialist encyclopedias are in print (Figure 2.2, “The six-volume Encyclopedia Lituanica, published from 1970 to 1980 in Boston, Massachusetts” shows one of these, the Encyclopedia Lituanica, an English-language six-volume encyclopedia on Lithuania). General encyclopedias have become household names: Encyclopaedia Britannica[3] and World Book for English speakers, the German Brockhaus, and the French Larousse. The Great Soviet Encyclopedia grew to 100,000 articles in Russian and produced encyclopedias in other languages of the USSR.

Late 17th Century: The Modern Encyclopedia

[edit | edit source]The encyclopedia as we know it today was strongly influenced by the 18th-century European Enlightenment. Wikipedia shares those roots, which includes the rational impetus to understand and document all areas of the world.

Jonathan Israel[4] cites the Grand Dictionnaire of Louis Moréri (Figure 2.3, “Louis Moréri (1643–1680), a pioneer of the modern encyclopedia”) as being the first modern encyclopedia. Published in 1674, it ran to many editions over half a century. Then, as now, times were changing: The previous decade's Royal Society of London was composed of amateurs, mostly outside the universities, but they were pioneers of learned society and the modern scientific method. The new media of the time were journals, such as the Royal Society's Philosophical Transactions, which were used to spread knowledge of scientific discoveries and theories. According to Israel, by the decade after Moreri's compilation appeared, the new institution of the learned journal threatened existing authority.

By the Enlightenment, the Renaissance concept of the polymathic uomo universale or universal man had been stretched to its limits. Science and exploration had added many facts to the body of knowledge, and no one person could grasp everything significant.

Encyclopedia editors made fields of knowledge available to the reading public by coordinating the efforts of leading scholars and intellectuals and condensing the available information. Israel writes that "these massive works … were expressly produced for a broad market." He mentions the "stupendous" 64-volume Zedler Universal-Lexicon in German (published 1731–1750); he also comments on the sheer expense of a well-stocked library at that time.[5] Access to general information was now available for the prosperous middle class; it was no longer confined to the rich and those actively involved in the intellectual networks.

The new generation of encyclopedias, of which the best-known is Denis Diderot's provocative French Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (Encyclopedia, or a systematic dictionary of the sciences, arts and crafts), were general works. They included all areas of knowledge, from the technical to the esoteric to the theological.

Wikipedia as an Encyclopedia

[edit | edit source]Wikipedia carries on these encyclopedist traditions but with some radical changes. The most obvious change is technological: Wikipedia stores information online, so its scope is not limited by the economics of printing.

Wiki page structure encourages many short articles rather than a few long ones. This works because pages are hypertext: a collection of articles linked back and forth. Earlier encyclopedias used footnotes and indexes as a way to link to other articles, but Wikipedia uses hypertext to its full potential, giving it a very different organizational style compared to the printed page. This extensive linking extends beyond articles in the English-language version: Wikipedias in different languages, from French to Swahili (Figure 2.4), are cross-referenced with tens of millions of links, as described further in Chapter 15, 200 Languages and Counting.

As described in Chapter 1, What's in Wikipedia?, Wikipedia editors encounter the same issues that the original encyclopedia editors did—what topics to include and how to present them—and address these issues by developing content standards and style guidelines. Articles should be concise surveys, not personal essays: complete, accurate, and objective. They should summarize topics quickly in the lead section, as dictionaries do. These stylistic guidelines help Wikipedia fulfill the encyclopedia's traditional function: People consult the site for rapid introductions to a subject, written for the general reader.

Wikipedia's scope is far greater than previous encyclopedic projects, however. Encyclopedias have traditionally been published as comprehensive guides to some defined area of knowledge. Wikipedia is instead a collection of both specialist and generalist encyclopedias, linked together into an integrated work. Its articles can be updated immediately: Articles are dynamic, and their content can change from day to day or even (in the case of current events) from minute to minute. Wikipedia's huge scale and rapid updating is possible in part because the authorship model is completely different from earlier projects: The idea of the famous author or expert-written article has been discarded.

Finally, unlike earlier encyclopedias, Wikipedia is a noncommercial project, and its content is deliberately licensed so others can freely use it. This ease of access alone is surely far beyond what the early encyclopedists hoped for.

The 1960s and 1970s: Unix, Networks, and Personal Computers

[edit | edit source]Looking ahead several hundred years, we'll now explore the technological part of Wikipedia's heritage: the free software movement, the development and widespread growth of the Internet and the personal computer, and the development of wiki technology.

During the late 1960s, two key developments in computing technology occurred. The first was the beginning of the modern operating system essential to networked computing. In the 1960s, the computers in the public eye were the hugely expensive S/360 series of mainframe computers from IBM, whose twitching tape drives became iconic for speedy electronic brainwork. Meanwhile, comparatively disregarded at the time, the Unix operating system at Bell Labs was created on a humble PDP-7 minicomputer from the Digital Equipment Corporation. (According to legend, the machine had been recycled after having been left in a corridor.) Unix ultimately became one of the most widely used operating systems for the servers that power the Internet, continuing to flourish long after the IBM mainframes became hardware dinosaurs and inspiring a variety of free software projects.

During this same time period, the groundwork for the network that would become the Internet was laid. Called ARPANET, the original Internet was a US Department of Defense project first theorized in the 1960s. Along with other networks, ARPANET provided some of the first connections to universities and research institutions. Later, the technology behind this network became available for new networks available to consumers: The first email service was offered by CompuServe in 1979, the same year newsgroup software was developed.

A decade later, Tim Berners-Lee would develop a networked implementation of the idea of hypertext, an idea that would become the World Wide Web. With the development of web browsers in the early 1990s, consumers, who had been buying personal computers since the mid-1970s (a phenomenon that became widespread with the introduction of the Apple II in 1977), could now "go online" and participate in the growing Internet. These developments, occurring over just a few decades, completely reshaped the modern world and made large online projects like Wikipedia possible. The advent of personal networked computing also provided the necessary technical background for the cultural ideas of free software and online communities, which are critical to Wikipedia's development.

The 1980s: The Free Software Movement

[edit | edit source]In the early 1980s, Richard M. Stallman, a software developer at MIT's Artificial Intelligence Lab, became alarmed at what he saw as a loss of freedom for computer programmers. Stallman had spent two decades working in a collegial environment, where changing or amending software was technically feasible and clear of legal worries. If someone needed someone else's computer program, he just asked for and adapted it.

As explained on Wikipedia:

- In the late 1970s and 1980s, the hacker culture that Stallman thrived in began to fragment. To prevent software from being used on their competitors' computers, most manufacturers stopped distributing source code and began using copyright and restrictive software licenses to limit or prohibit copying and redistribution. Such proprietary software had existed before, and it became apparent that it would become the norm. ...

- In 1980, Stallman and some other hackers at the AI lab were not given the source code of the software for the Xerox 9700 laser printer (code-named Dover), the industry's first. (From Richard Stallman, April 2007)

While Stallman and other hackers had been able to customize another lab printer so that a message was sent to users trying to print when there was a paper jam, they could not do so with Dover—a major inconvenience, as the printer was on a different floor. Stallman asked for the printer software but was refused; this experience and others convinced Stallman of the ethical need for free software.

Software, now produced by companies such as Microsoft, was owned and controlled, and sharing it entailed breaking a license and breaking the law. Source code—the version of a program necessary to make changes—was frequently not made available. You couldn't customize software, even after you paid for it.

In 1983, Stallman announced the GNU operating system project and two years later founded the Free Software Foundation. In an essay titled "What is Free Software?" Stallman declared the freedoms essential for free software:

- The freedom to run the program for any purpose

- The freedom to study how the program works and adapt it to your needs

- The freedom to redistribute copies so you can help your neighbor

- The freedom to improve the program and release your improvements to the public so the whole community benefits

The GNU project (whose logo, appropriately enough, features a gnu—see Figure 2.5, “The GNU project logo”) set out to build a completely free operating system, inspired by Unix. The acronym GNU was a programmer's joke that stood for GNU's Not Unix. A collaborative project, GNU was largely functional by the early 1990s. In 1991, a young Finnish programmer named Linus Torvalds offered one of the last essential remaining pieces, a kernel.

Torvalds called his project Linux. The combined system of GNU software run on this kernel is known as GNU/Linux and is now widely used by both individuals and corporations. Hundreds of people worldwide have contributed to Linux.[6]

This operating system, which has become the basis of numerous distributions developed for different purposes, has been one of the great successes of the free software movement. Some versions of GNU/Linux are distributed commercially, such as Red Hat Linux. The ideas behind free software have become widespread; other successful examples of free software projects are the Apache software, on which many servers run, and the Mozilla web browser, which millions of people use. Today, freely licensed, collaboratively built software supports work by businesses and individuals worldwide.

GNU developers recognized that new software licenses, which differed from traditional ideas of copyright, needed to be created to preserve the freedom to share these programs legally. Although the rights assigned with copyright have been of concern for a long time—a mention is made of copyright in the US Constitution, which grants Congress the power to "promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries"—the advent of the personal computer and the Internet have magnified and broadened copyright issues. Broadly speaking, copyright law assigns the author of a creative work certain exclusive rights to sell and distribute that work, keeping others from copying and profiting from an author's work without permission. Today, copyright is assigned automatically in the United States and in many other countries when a work is created. However, because copying a work, such as a computer file, is now quick, routine, and costs virtually nothing, many questions have been raised about the place and effectiveness of copyright law in an electronic environment.

As an alternative to traditional copyright, Stallman created the General Public License (GPL) in 1989; today, this license is widely used for free software. This license is an example of copyleft—a movement to protect the freedom of creative works by using new licensing arrangements that incorporate ideas from free software.

As usual, Wikipedia has plenty to say on the matter:

- Copyleft is a play on the word copyright and is the practice of using copyright law to remove restrictions on distributing copies and modified versions of a work for others and requiring that the same freedoms be preserved in modified versions.

- Copyleft is a form of licensing and may be used to modify copyrights for works such as computer software, documents, music, and art. In general, copyright law allows an author to prohibit others from reproducing, adapting, or distributing copies of the author's work. In contrast, an author may, through a copyleft licensing scheme, give every person who receives a copy of a work permission to reproduce, adapt or distribute the work as long as any resulting copies or adaptations are also bound by the same copyleft licensing scheme. (From Copyleft, April 2007)

By the turn of the 21st century, free software ideas had spread well beyond computer code. In 2000, Stallman created the GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL). The GFDL was conceived of as a complementary license to the GPL but was intended for written works such as software documentation rather than code. Wikipedia adopted the GFDL early on as its license for all content created on the site—a move that guarantees the site's content will remain perpetually free for everyone to use and redistribute.

Wikipedia and the Free Perspective

[edit | edit source]Wikipedia's approach is tied to the ideals of the free software movement. Both the software on which Wikipedia runs (MediaWiki) and the site's content are freely available for use by anyone to adapt and modify, qualified only by the requirements of their respective GPL and GFDL licenses. Wikipedia's slogan is Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. No one has to pay to view Wikipedia articles, but free means more than that: Free also means "no strings attached," and this is the consistent goal of the Wikimedia projects. Freedom means free of cost, free of restrictions to change and modify any content, free to redistribute, free for anyone to participate, and free of commercial influences.[7] The GFDL license specifies that any work placed under it may be legally reused and republished by anyone, with the only restriction being that any such republishing must itself also be licensed under the GFDL (and the original authors must be credited). In other words, the license ensures that any GFDL-licensed content is both freely available and open to all. Though contributors to Wikipedia do retain the copyrights to their work, they lose the right to specify what can be done with it.

Thus another site can repackage and profit from Wikipedia articles, as long as it respects the license. In fact, there are many legitimate sites like this, called mirror sites, and anyone using a search engine will come across them often. The only rules are that if a site does copy Wikipedia material, those pages must also be licensed under the GFDL and must acknowledge the content's origin. Because of this clause, the GFDL is sometimes called a viral license: It propagates and perpetuates itself.

Any author adding to Wikipedia should know what the license means. If having personal control over your work matters to you, you should not add it to Wikipedia. Once you have saved your contributions to the site, you've conceded that others can modify them and use them in any way they wish under the licensing terms.

Other works using the GFDL include the book you're reading; its text may be reused under the same conditions. The GFDL requires a history of authorship; on Wikipedia, you can look up the full list of original authors of articles (including pseudonyms, automated edits, and IP numbers) on the page histories of every Wikipedia page we cite. You'll find more about the GFDL and reuse compliance in Appendixes Appendix A, Reusing Wikimedia Content and Appendix E, History.

1995: Ward's Wiki

[edit | edit source]Tim Berners-Lee, the pioneer of the World Wide Web's technology, has said he always intended for the Web to be interactive. The social and cooperative side of Internet usage is now catching up with that potential, and wiki sites are just one part of a larger pattern.

A wiki is a type of website that anyone can edit. Setting up a wiki creates an effective tool for collaborative group authoring. Simply speaking, a wiki is a collection of web pages, located at a common address on the World Wide Web, that link to each other through their page titles and can be edited online by contributors without special permissions. More technically, a wiki is a kind of database, consisting of pages of HTML, the markup language used on the Web, but wiki pages can be edited by contributors using a simpler markup language.

Structurally, a wiki can contain multiple discussions consisting of many topics and is by its very nature dynamic and changing. Most wikis record the changes that are made to them, keep previous versions of pages, and make it very simple to add clickable links from one page to another page on the site. Openness is a key feature of most wikis as well. You don't need much technical knowledge or special permission to edit most wiki pages; instead, you can change them as you see fit. Wiki pages contrast with conventional web pages that have largely static and uneditable content.

The wiki concept and the name come from Howard G. "Ward" Cunningham, an American computer programmer. Instead of calling his idea QuickWeb, his first idea, he chose the Hawaiian term wiki wiki when setting up his website, WikiWikiWeb:

- In order to make the exchange of ideas between programmers easier, Ward Cunningham started developing the WikiWikiWeb in 1994 based on the ideas developed in HyperCard stacks that he built in the late 1980s. He installed the WikiWikiWeb on his company Cunningham & Cunningham's website c2.com on March 25, 1995. Cunningham named WikiWikiWeb that way because he remembered a Honolulu International Airport counter employee telling him to take the so-called "Wiki Wiki" Chance RT-52 shuttle bus line that runs between the airport's terminals. "Wiki Wiki" is a reduplication of "wiki," a Hawaiian-language word for fast. (From w:WikiWikiWeb, April 2007)

On this original wiki site, meant for the Portland Pattern Repository (Figure 2.6, “The front page of the original wiki at ”), programmers exchanged ideas on patterns and approaches to programming, forming a somewhat rambling but fruitful discussion space.

In its original concept, a wiki expresses the views of a community with some common interest and brings people together in a shared space for discussing ideas and building resources. The main point of a wiki website is to make it easy for contributors to collaborate in building its content, whatever that content may be. If the site is wide open, what "the community" is may be nebulous, but a wiki community is often simply defined as those people who are editing the site.

A wiki, then, is not simply a technology but a whole approach for a group using a website to collaborate. This approach, which you could call a philosophy, cannot really be expressed by looking at single users or editors: Wikis have a collective aspect. In this, wikis are related to and draw from the culture of other online and open source communities.

1997: Open Source Communities

[edit | edit source]For software to be freely available is one thing, for many people to contribute to building the software is another. In an influential 1997 essay, "The Cathedral and the Bazaar," Eric S. Raymond drew on the recent history of Linux development and argued that the open nature of free software allowed for widescale collaboration and development. Raymond coined a new term, open source, with a definition similar to the idea of free software. In the late 1990s, a group of Bay Area computer programmers and Raymond developed an open source movement, which also centered around sharable software but particularly emphasized the pragmatic benefits of collaboratively developed software to companies.

Raymond described how opening up software projects by making source code available and using open development processes could ultimately produce better software by increasing the number of people able to work on it. He coined the aphorism, "Given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow," which emphasizes how many different people, all concerned with understanding a program, help to find mistakes and other weaknesses and get them fixed quickly. In the essay, he also writes about the other benefits of using a self-selected group of collaborators who are only acting out of their own passion for the project:

- ...contributions [to Linux] are received not from a random sample, but from people who are interested enough to use the software, learn about how it works, attempt to find solutions to problems they encounter, and actually produce an apparently reasonable fix. Anyone who passes all these filters is highly likely to have something useful to contribute. (From Eric S. Raymond, "The Cathedral and the Bazaar," presented at Linux Kongress, 1997)

Figure 2.6. The front page of the original wiki at http://c2.com/cgi/wiki

In a comparable way, Wikipedia urges its many readers to become writers, fact-checkers, and copyeditors, allowing anyone to ask a question or fix incorrect information. In a broad sense, the ideas of shared improvement and collective scrutiny are common to wikis, free software, and the concept of an encyclopedia that anyone can edit.

2000: Online Community Dynamics

[edit | edit source]Wikipedia is famous for fostering an elaborate, unusual volunteer community, but Wikipedia is far from being the first online community or the first wiki community. Other groups had already explored the ideas that would become the basis of Wikipedia's social principles.

Dedicated virtual communities have been around since the very beginning of computer networks. As the Internet has grown, hundreds of online communities have developed, each with its own mores and traditions. The idea of community suggests a focus on the individual people involved and how they interact as being key to understanding how these groups function. Wikipedia suggests a definition of a virtual community as being simply "a social network with a common interest, idea, task or goal that interacts in a virtual society across time, geographical and organizational boundaries and is able to develop personal relationships." For instance, some early notable online communities include the following (adapted from w:Virtual community):

- Usenet, established in 1980 as a distributed Internet discussion system, was one of the first highly developed online communities with volunteer moderators

- The WELL, established in 1985, pioneered some aspects of online community culture with many users voluntarily contributing to community building and maintenance (for example, as conference hosts).

- AOL offered various forms of chat and gaming from its inception in 1983 and later helped pioneer the contemporary "chatroom." These chatrooms were initially moderated by volunteer community leaders and helped propel AOL to its position as the largest of the online service providers.

The new wiki communities in the late 1990s started with the idea of interacting online, which had been developed by these and many other online communities, and then added the ideas of open mass collaboration articulated by the growing free and open source software movement. But as wikis matured, they had to develop new ideas and principles for how people could collaborate fruitfully on such open, radically different websites.

The people working on the original WikiWikiWeb coined terms and developed ideas that would later become influential in other wiki communities, for instance, that people could take on different roles such as wiki gnomes, who beaver around on the site fixing small points of format and style. They also noticed that content could develop on a wiki in various ways (some better than others), for example, as walled gardens, dense areas of content that the average editor found hard to access.

The conversation continued on one small but influential wiki, MeatballWiki, which was set up in April 2000 by the Canadian Sunir Shah. This wiki attracted those interested in discussing online communities and their dynamics and typical issues. Much of the conversation on MeatballWiki was about the ways in which individual editors tended to respond to the freedom of editing a wiki. The concepts of soft security (security through group dynamics rather than hard-coded limits) and the right to leave (someone should be able to both join and leave a wiki community easily and gracefully) were first discussed here. Users also discussed large-scale concepts that affected the whole community, such as forking and interwiki connections—communities splitting apart or coming together. MeatballWiki continues today, full of essays, discussions, arguments, and musings about what constitutes a healthy, successful online community and what it means to work on a wiki.

Thus, the WikiWikiWeb, MeatballWiki, and other early sites developed the terminology and articulated the principles of structuring community that many wikis, including Wikipedia, operate with today. Wikipedia, in turn, has gone on to apply these ideas in large-scale ways not imagined by these early wikis.

Wikipedia as a Wiki Community

[edit | edit source]Wikipedia developed in an atmosphere where wikis were already established as a particular kind of online community. The word wiki is sometimes interpreted as a backronym, a back-formed acronym, as if it stood for W-I-K-I. In the style of Internet abbreviations, you could read this as What I Know Is, referring to the knowledge contribution, storage, and exchange functions of wikis. A typical wiki is still reminiscent of notes on an extended brainstorming session: The hypertext structure makes it possible to take up any point in its own smaller discussion thread. The early wikis were precursors to Wikipedia, not only in terms of technology, but also because people saw wiki editing, from the start, as a way to share knowledge. Wikipedia, however, changed the model of wikis from being a continuing conversation among peers to being a project for collating information and building a reference resource—and in so doing, showed that you could build a single work with a large, disparate online community spanning language and geography.

Being a wiki site is not intrinsic to Wikipedia's content. The adaptation of wiki technology, however, has been key to Wikipedia's quick success in an area where previous projects have failed. From the point of view of a technology historian, Wikipedia already deserves to be called a killer app, the sort of application of a technology that in itself justifies the success of wikis. Wikipedia has used its wiki aspects successfully to collate and develop the world's largest encyclopedia so far.

Embracing the history of encyclopedias, the openness of free software, and the easily accessible, collaborative aspects of online communities and wikis meant that Wikipedia was able to draw on both a large pool of technically aware people who saw the benefits of the free software movement as well as many nontechnical people who were attracted to the encyclopedic mission and community structure. A high level of collaboration has been possible in areas that would have been difficult to foresee. For instance, current events articles are rapidly updated, often with a thousand or more edits from hundreds of people in a single day, demonstrating the extraordinarily responsive power of this collaborative tool.

2001: Wikipedia Goes Live

[edit | edit source]Wikipedia has been an evolving phenomenon from the start. It has grown rapidly and has steadily attracted more attention.

Wikipedia's immediate predecessor was Nupedia. (This was not the first Internet encyclopedia idea, however; Interpedia, a project from 1993, never got off the drawing board.) Nupedia was started by Jimmy Wales, with Larry Sanger serving as editor-in-chief. The project was supported by Bomis, an Internet portal company founded and run by Wales and Tim Shell. Nupedia sought to provide an online encyclopedia website under a free-content license, built from contributed articles. Its model was more conventional, though; it was not a wiki, and contributors were expected to be experts in their fields. The pieces they submitted would only be published to the site after an extensive peer review process. The momentum of the project became lost in these multiple review stages, and only a few articles were ever completed.

Wikipedia was created on January 15, 2001, as an alternative based on an open wiki site. Initially, the site was presented as a way to attract new contributors and articles to Nupedia. (Both Sanger and Wales participated in developing the site in the early days, and there was later some dispute over whether they were "co-founders" of Wikipedia. Sanger left the project in 2002, while Wales continues to play a leading role in Wikipedia today.) To differentiate the site from Nupedia, the new project was named Wikipedia.

Wikipedia was immediately successful. Its wiki setup lowered the barriers to entry, and its reputation grew by word-of-mouth alone—the site has never advertised directly. A few key mentions on popular websites drew notice to the site; in March 2001, a posting was made on the Slashdot website, and in July of that year, it received a prominent pointer in a story on the community-edited technology and culture website Kuro5hin. These stories brought surges of traffic to Wikipedia, including people with technical savvy. Search engines, especially Google, also brought hundreds of new visitors to the site every day. The first major coverage in the mainstream media was in the New York Times on September 20, 2001.

By mid-2001, Wikipedia was beginning to acquire an identity of its own (Figure 2.7, “The Wikipedia logo used from late 2001 until 2003. This logo was designed by a volunteer called The Cunctator and was the winner in an open logo contest. See the progression of the Wikipedia logo over time at .”). Versions in Catalan, Chinese, German, French, Hebrew, Italian, Spanish, Japanese, Russian, Portuguese, and Esperanto had been created, and technical support had been set up (mostly far from the public gaze, as Jimmy Wales chatted on IRC and discussed issues on the mailing list). More visitors meant more articles were written and also more edits were made to improve existing articles (just as important, if a little harder to quantify). The Recent Changes page showed increasing activity. The project passed 1,000 articles around February 12, 2001 and 10,000 articles around September 7, 2001 (see Figure 2.8, “Wikipedia as it appeared in late 2001 (from the Nostalgia wiki, , a browsable version of a snapshot of Wikipedia from 2001)” for how Wikipedia appeared around December 2001). Nupedia, by contrast, only completed some 24 finished articles over its lifespan from 2000 to 2003.

Wikipedia Today

[edit | edit source]Today, Wikipedia is a household word (at least in households with access to the Web). By late 2007, the site had become the #8 most visited website worldwide, as measured by Alexa ratings,[8] and the volunteer-based community organization behind Wikipedia has become highly complex, learning from past mistakes and developing institutions. Wikipedia is not only a piece of hypertext; the site is by far the largest and most inclusive cross-referenced single collection of factual information to ever exist. Due in part to this assiduous cross-linking of content, Wikipedia articles are prominent in search engine results; many (if not most) queries on the Web can be answered with a Wikipedia article. Wikipedia is an Internet phenomenon, unlike anything seen before—and it could not have technically existed on a comparable scale until quite recently.

During the early years, Wikipedia was administered (technically, financially, and socially) entirely by volunteers. The hardware and personnel needed to run the site was donated by Bomis. As time passed, however, Wikipedia's needs outstripped the ability of Bomis to meet them. The site's infrastructure (but not its content) is now run by the nonprofit Wikimedia Foundation (WMF), which will be described in depth in Chapter 17, The Foundation and Project Coordination.

The WMF, employing a very small staff and governed by a board of directors, has taken on the role of coordinating a very large and disparate group of volunteers from around the world: By 2008, Wikipedias existed in over 250 languages. The Foundation serves as the parent organization for all Wikipedias and sister projects (these other reference projects are described in Chapter 16, Wikimedia Commons and Other Sister Projects). Initially based in St. Petersburg, Florida, the WMF moved to San Francisco early in 2008. However, most of the servers that provide Wikipedia's infrastructure are still hosted in Florida, with additional servers in Europe and South Korea.

The Foundation's goals have remained in line with the ideal of volunteers freely creating content and distributing the world's information. Its mission statement is, in part,

- to empower and engage people around the world to collect and develop educational content under a free license or in the public domain, and to disseminate it effectively and globally.... The Foundation will make and keep useful information from its projects available on the Internet free of charge, in perpetuity.

The rest of the story of Wikipedia belongs in Part IV. There we'll tell you about the current gamut of projects in many languages and about the Wikimedia Foundation. The key ingredients for these projects and the Foundation were already in place after the first six months: developers to work on the software, open authorship of content, an international and multilingual group of contributors, word-of-mouth publicity, and a loose but effective central control of infrastructure, with community-driven lightweight editorial mechanisms.

Unfinished Business

[edit | edit source]Wikipedia's growth is still entirely open ended—the project has simplified the problem of where to stop by completely disregarding that question. The number of articles on the English-language Wikipedia might still grow by a factor of three or four, or even more. For instance, information about geography, if added to the same depth for the rest of the world as it has been already for the United States, could swell the English-language Wikipedia to a size between 5 and 10 million articles.

There are better questions to ask, however, than simply concentrating on future growth. How easy is it to find fresh encyclopedic topics? When will the editing community switch to focusing on greater depth and quality for each individual article, rather than on greater breadth of coverage overall? This may well be happening already: Quality of content is becoming just as important as quantity (see Chapter 7, Cleanup, Projects, and Processes for more on these quality-focused projects and how to get involved).

Enquire Within Upon Everything was a bestselling Victorian reference and how-to book, first published in 1856 (and referenced in the name of Tim Berners-Lee's early web precursor project ENQUIRE). This would perhaps be a better title for Wikipedia, which is gradually becoming a reference about everything. But some caution is still required when using Wikipedia (see Chapter 4, Understanding and Evaluating an Article), and this is to be expected; the wiki culture has a deep acceptance of imperfection and incompleteness as both inevitable and perhaps even necessary for inspiring a working community.

- Further Reading

Encyclopedias

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Encyclopedia#History A brief history of encyclopedias

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_encyclopedias A list of encyclopedias

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_encyclopedia_project Information about projects to build an online encyclopedia

Free Software and Open Source

http://www.fsf.org/ The Free Software Foundation

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Stallman A biography of Richard Stallman

http://www.catb.org/~esr/writings/cathedral-bazaar/ The text of Eric Raymond's essay, "The Cathedral and the Bazaar"

Wikis and Communities

http://c2.com/cgi/wiki?WelcomeVisitors c2.com, the first and original WikiWikiWeb

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wiki About wikis, from Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_wikis The history of wikis

http://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Interwiki_map Meta page on interwiki prefixes

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtual_community Virtual or online communities

http://www.usemod.com/cgi-bin/mb.pl?WikiPediaIsNotTypical An essay from MeatballWiki, "WikiPediaIsNotTypical"

Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia#History The history of Wikipedia, from Wikipedia

http://wikimediafoundation.org/wiki/Mission_statement The WMF mission statement

http://www.alexa.com/data/details/traffic_details/wikipedia.org Alexa traffic details, for the Wikipedia sites

http://reagle.org/joseph/2005/historical/digital-works.html An essay by Joseph Reagle, "Wikipedia's Heritage: Vision, Pragmatics, and Happenstance," on Wikipedia's influences and early history

The Wikipedia Model Debated

[edit | edit source]Wikipedia has been extraordinarily successful in its mission of producing a widely used, free-content encyclopedia in many languages. This success is reflected both in the very high use of the site and in the well-developed global community of dedicated volunteers that produce Wikipedia. However, Wikipedia is unfinished and far from being perfect, and this is reflected in the press about the site. Outside news stories about the site are often not "good news" about more free content. The media shows a greater interest in the "bad news" about the site's failings, which means many people first hear about Wikipedia in critical commentaries, usually about inaccuracies.

Over time, Wikipedia has acquired many critics, and hundreds of stories have been published about flaws in Wikipedia's coverage. Some discuss problems with individual articles, while others comment negatively on Wikipedia's overall policies and governance. Some also critique the entire idea behind Wikipedia. This criticism is not limited to outside media: Internally, contributors spend a great deal of time discussing how Wikipedia works and how to improve it.

In this section, we'll highlight some common objections to Wikipedia's working model: the potential for misinformation, academic respectability, and a lack of respect for expert and authoritative opinions and openness to amateur editors. We'll describe a few real-life case studies and critiques and describe Wikipedia's response. None of these objections are settled issues with easy answers; Wikipedia continues to refine its model. We encourage you, as you read through this book and learn more about how Wikipedia works, to consider these and other questions in forming your own opinion.

Misinformation: The Seigenthaler Scandal

[edit | edit source]In May 2005, a defamatory article slipped past the New Pages Patrol, the informal group of Wikipedia editors who check new articles as they are created. An anonymous hoaxer inserted a short fabricated biography, just five sentences, in the article covering John Seigenthaler, Sr., a distinguished American journalist who had served in the Justice Department of the Kennedy White House. The text suggested that Seigenthaler was connected to the Kennedy assassinations. No one noticed for five months—until September 2005 when the prank was revealed and made headlines.

A friend of Seigenthaler's originally discovered the article; he alerted Seigenthaler, who in turn contacted Jimmy Wales to complain. The objectionable content was deleted from the live page almost immediately after being noticed, by September 24, 2005; in early October, the article was then deleted altogether so the objectionable version could not be viewed from the page history (an accurate biography was subsequently re-created). Because Wikipedia content is mirrored on other sites, Seigenthaler also had to request his biography be removed at some of these sites, such as Answers.com and Reference.com.

The matter did not rest there, however. Seigenthaler published a guest editorial in November of that year in USA Today.[9] In it, he talks about his "Internet character assassination," damns the "poison-pen intellects" loose on the Internet, and calls Wikipedia a flawed research tool. This sparked off several other articles about the site and interviews with both Seigenthaler and Jimmy Wales.[10]

The whole event was something of a defining moment for the site. The national news story of the vandalized Seigenthaler biography brought home the point that Wikipedia was now prominent enough that the accuracy of an article mattered—defamatory or inaccurate content really could harm individuals. Before the Seigenthaler scandal, Wikipedia contributors tended to accept that some incorrect content was on the site and held to the philosophy of "so fix it." This idea, which is still a core part of Wikipedia's basic philosophy, holds that on an open wiki where anyone can contribute, anyone who spots something wrong can—and should—also fix it themselves. The Seigenthaler incident prompted an intense effort to write more accurately sourced articles, to institute a zero-tolerance environment for nonsense, and to recognize that people who have no desire to work on the site themselves may be affected by Wikipedia articles.

Several procedural changes also followed in the wake of this story and the issues attendant with the tremendous growth Wikipedia experienced at the end of 2005. One development was the policy on biographies of living people (Wikipedia:Biographies of living persons, shortcut WP:BLP). This policy holds such biographies to strict compliance with Verifiability and No Original Research and discusses how to maintain the Neutral Point of View policy when dealing with negative and irrelevant information or information that is out of balance with the rest of the article. Violating this policy by inserting gossip or defamatory content is very serious; the article or the revision in question may be deleted, and ongoing violations may lead to an editor being blocked from editing. To deal with article complaints, Wikipedia also set up an email address and answering mechanism staffed by trusted volunteers.

In December 2005, anonymous article creation from IP addresses was stopped. You must now register and log in to create an article (see Chapter 6, Good Writing and Research). This policy helped cut down on the number of nonsense pages being created, pages that site administrators had to delete, which had become a huge amount of work—on the order of thousands of pages a day. Some question whether this measure is effective, and in the future, Wikipedia may experiment with turning anonymous article creation back on to see how much of a difference it makes.

One of the scandal's side-effects has been that people working in the media—and anyone whose name has been in the news—now tend to check whether they have a Wikipedia page, and many request to have the page changed (or in some cases, deleted). Editors treat such requests carefully, however. They consider the issue of neutrality and accurate sourcing and will not change articles simply to meet the wishes of the subject.

John Seigenthaler's sermon about the responsible use of Wikipedia's growing media power has not fallen on deaf ears. The possibility that an article can slip through the cracks is very real. Many increasingly sophisticated mechanisms to watch for and correct bad content have been created (see Chapter 7, Cleanup, Projects, and Processes), but Wikipedia's openness—a key value—means that something incorrect may be submitted and go unnoticed until it causes trouble.

Amateur Contributors, Authority, and Academia

[edit | edit source]Any Wikipedia contributor can be anonymous, and most are pseudonymous. Contributors are under no obligation whatsoever to reveal who they are "in real life," and the majority do not. You can't really know the details of an author's experience with a topic unless he or she volunteers that information. And experience is not supposed to matter: Whether someone is a college professor or a high school student, what matters is whether he or she respects Wikipedia's rules and contributes productively to the encyclopedia. This principle has been of primary importance since the beginning: An author's or editor's background should not affect his or her standing as a Wikipedia contributor.

By the same token, the content policies set out in Chapter 1, What's in Wikipedia? (particularly Verifiability) apply to everyone. Wikipedia does not simply accept arguments from authorities. Even widely known experts in a field have to support all claims they make by including appropriate references to published literature (at least in principle).

Given this, many questions arise. If most contributors are semi-anonymous, does it matter if someone lies about who he or she is? Is Wikipedia anti-academic? Does it harm itself by not respecting experts' opinions enough? And is the site credible, given that amateurs have built it?

In this section, we'll look at different aspects of authority and criticisms of the Wikipedia model.

Wikipedia and Academic Authority

[edit | edit source]Wikipedia has an uneven reputation with educators; some see it as having low quality, and others train students to use Wikipedia appropriately. Many colleges have now made it clear that citations from Wikipedia are not acceptable in term papers.[11] Wikipedia fails some tests of academic respectability for two basic reasons.

One is concern about the quality and accuracy of Wikipedia content, which certainly varies across the site. The other, more fundamental reason is that college-level teaching can properly view encyclopedia articles, of whatever standard, as being for the lazy student. Students should do their own research.

Those who work on Wikipedia would generally agree. Articles are intended to give quick access to information, and Wikipedia's references to scholarly works are meant to facilitate study, not replace it. Students should follow up on the references given in articles and research a topic in other sources too. Writing an essay by paraphrasing Wikipedia is not acceptable, and of course copying Wikipedia directly deserves a grade of F. Unfortunately, students can easily use the site in place of other sources. (See Appendix B, Wikipedia for Teachers for specific advice for educators using and concerned about Wikipedia.)

Wikipedia and Experts

[edit | edit source]The need to find supporting references for statements in articles (enshrined in the Verifiability and No Original Research policies) is connected to the way that controversies are handled on the site, particularly questions of contributor expertise. If you post something at all debatable, whatever your standing in the field, you must allow others to question it. Statements should make clear who said what and where, and neutrality means you include the full range of opinions. You can't just insert your expert knowledge as Wikipedia content, with no references to back up your work.

Wikipedia, therefore, has an egalitarian policy for editors. An expert has the same privileges as any other editor: Expertise must manifest itself through the editing and discussion process. The general argument is that if you're an expert in a topic, you have probably spent some years looking at the literature and should know the relevant publications to cite, so you can follow the policies with ease. The requirement to cite is a concession to the general, skeptical reader and rules out any arguments along the lines of "because I say so, and you should just accept that." If you write extemporaneously, without citing your sources, be prepared for questions along the line of "How do you know?" This challenge will happen to expert and non-expert contributors alike.

Some have argued that this leveling approach to the Wikipedia model is simply wrong. One formulation of this argument is that asking experts and professors for scholarly support for their opinions is disrespectful. Another is that Wikipedia is actively hostile to experts and expert knowledge, forcing even the most knowledgeable in a field to be challenged by extreme skeptics and amateurs.

A mismatch between the encyclopedic tradition of giving conclusions and leaving out some of the reasons why and the emphasis on giving full details and sourcing can occur. Even the reliance on reliable sources can be problematic. Reliable sources should be cited, but who determines which sources are reliable? Criticism of sources should be fair-minded, but experts can sound argumentative or too quick in their judgment to outsiders.

The solution Wikipedia offers to these difficulties is the dedicated discussion pages attached to articles. On a discussion page, you can query and clarify steps in arguments that are made in articles, as well as question the source of these statements. If, for example, the status of some book is in question, a hostile review can be brought up on the discussion page, even though it would be misplaced in the article itself. However, discussion alone sometimes can't solve conflicts involving questions of expertise, as shown in the following case studies. If the skeptic feels the expert is dodging the issue, but the expert is just trying to be concise, neither side will be satisfied.

Case Studies in Academic Authority

[edit | edit source]Wikipedia's interface with academia matters greatly to its progress, but academic authority alone is not sufficient for making one's case on Wikipedia. Wikipedia's approach in this matter has been shaped by real-world experience—including editing disputes, scandals, and matters that have been through the on-site judicial system. When contributors work pseudonymously, their qualifications must be either taken on trust or ignored. In addition, Wikipedia's history shows that even confirmed academic credentials are not a realistic safeguard against editorial clashes on the site. Editing by those holding credentials can be contested.

A contentious and highly visible area of science, the issue of climate change and its possible causes, led to one drama on Wikipedia in 2005. Many articles were involved; at this time, nearly 100 articles on climatologists, over 100 articles on global warming skeptics, and around 100 articles on the science of global warming exist (you can find these in the subcategories under w:Category:Climatology).

William M. Connolley, an academic climatologist, edits Wikipedia under his real name. Connolley ran into trouble monitoring and updating climate change pages when confronted with extreme skeptics who were also editing the climate change articles. Sheer disbelief can undermine any attempt to write sensible scientific material in accordance with consensus views, and in this case, the controversy led to edit warring between the two sides.

Due to this dispute, Connolley was sanctioned by the Arbitration Committee, the formal body of volunteer editors who help regulate and resolve disputes on the site and have the power to sanction editors if necessary (see Chapter 14, Disputes, Blocks, and Bans).[12] His sanctions consisted of a revert parole—he could only undo one change a day made by another editor, a move designed to help prevent edit warring. These sanctions were later reconsidered and dropped. Throughout the case, Connolley's qualifications to write on climate topics were not an issue; the ability to edit productively and in harmony with other editors has little to do with one's knowledge of a subject.

In a later case on pseudoscience from late 2006 (Wikipedia:Requests for arbitration/Pseudoscience), Wikipedia's view of academic authority was further clarified. The underlying issue had to do with neutrality (NPOV) and its implications for representing all major points of view when the matter in question was scientific. This ruling by the Arbitration Committee went more clearly with mainstream science; the scientific consensus is expected to predominate in scientific articles. The relevant principle read, "Wikipedia:Neutral point of view, a fundamental policy, requires fair representation of significant alternatives to scientific orthodoxy. Significant alternatives, in this case, refers to legitimate scientific disagreement, as opposed to pseudoscience."

A third case along these lines involved Carl Hewitt, an Emeritus Associate Professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who was banned from editing certain articles on the English-language Wikipedia.[13] Arbitration committee rulings determined that he violated the Neutral Point of View policy and overstated the importance of his own contributions (and those of his students) in theoretical computer science and some other areas such as quantum mechanics and the sociology of science. The issue here is not the demarcation of the academic and non-academic approaches, but rather that Wikipedia articles, as surveys of academic literature, must not give undue weight to one approach. One affected area was logic programming, the basic technology of the "fifth generation computing" project. Here Hewitt overstepped the policy on No Original Research, attempting to impose his own definition of the field in the article.[14]

These cases all illustrate specific difficulties with the Wikipedia model. Academics and other experts are subject to the same policies, on conduct and content, that apply to everyone else on the site. These cases differ, however. Hewitt's approach violated the letter and spirit of Neutral Point of View, clearly causing a conflict of interest. Experts are not immune to human failings and passion. Connolley's problems with troublesome non-experts were short-lived because of his patience with the sanctions and with other editors; his substantiation of his own contributions was never an issue. A neutral point of view is simply not negotiable on Wikipedia, no matter how great your expertise.

Pseudonyms and Claimed Expertise

[edit | edit source]The role of editors' authority and expertise has also been debated in regards to what editors can say about themselves. The case of User:Essjay, real name Ryan Jordan, came to light in the Spring of 2007 and was prominent in the news for some time.

Essjay was a well-respected and experienced editor on the English-language Wikipedia, holding several trusted administrative positions. He also claimed anonymity, not revealing his real name or identity on the site, but did claim on his user page that he had a theology doctorate and an academic teaching position. He typically worked on the administrative and process side of the site, rather than on content, and became respected as a fair and committed Wikipedian.

In 2006, Essjay was interviewed for a lengthy piece in The New Yorker[15] and continued to state that he was an academic. This was later determined to be untrue—Jordan was really a young student without experience in theology—and by misleading the journalist he embarrassed Wikipedia. After the scandal broke, he resigned from the site. Questions remain as to whether he had ever used his claimed expertise to influence content and ultimately whether claimed (but false) topical expertise mattered when considering his well-documented skills as an editor on Wikipedia. Any attempts to influence the content of articles should have been ignored by anyone aware of Wikipedia's doctrine on not arguing from authority, but whether this was the case or not is open to debate. See Chapter 11, Becoming a Wikipedian for more on user pages and advice on what to post there.

The Crowd of Amateurs

[edit | edit source]In these first two chapters, you have seen an outline of Wikipedia's model for content. There have been a few tweaks through the years, but the basic ideas of what material Wikipedia wants to gather, the way it is presented and distributed, and why things are done one way and not another have not changed much over time. That does leave a few questions. Who does the writing and editing? Is the site really an open free-for-all, or is there real project management and bureaucracy behind the scenes? These points are addressed later in this book (see Chapter 12, Community and Communication and Chapter 7, Cleanup, Projects, and Processes, respectively), but the answers, in terms of how Wikipedia works, are complex.

Going hand in hand with the criticism of Wikipedia as being hostile to experts is a related criticism about the community of editors—that Wikipedia relies on amateurs.[16] One common claim is that the only thing behind Wikipedia's success is a group of amateur writers, lacking the necessary expertise to produce a good reference work. Another criticism is that Wikipedia's framing of the issue of expertise is part of a larger problem with Internet culture. (Extensive discussion of Wikipedia's "business model" from this angle has ensued, which may be beside the point, given Wikipedia's status as a nonprofit initiative.)

Is documented contributor expertise necessary to write a great encyclopedia? The answer requires some qualification. Not all Wikipedians are amateurs; many are academics (though they may not write articles in their area of expertise). And when sources are considered, expertise is not rejected at all: Expert-written materials are the most desirable sources for articles on the site. Refer to the mission to clarify what the goal actually is. Wikipedia is building a huge compilation of materials and facts, many of which come from traditional sources, with the content policies simply acting as standards applied to everything submitted. Thinking of Wikipedians as the new encyclopedists makes sense, but, saying it more precisely, they're engaged in creating a new kind of tertiary source, for a networked world, delivered free.

Clearly, though, without widespread and open participation, the world's largest reference work could not have been created in less than a decade.[17] In contrast to the criticism of the site as being created by amateurs, many consider Wikipedia's harnessing of the masses to write a new kind of reference as a brilliant stroke—this new approach simply has a new set of strengths and weaknesses, as all new media do. For example, very rapid updates are both a strong and a weak point in the model, and this takes some getting used to.

Wikipedia has also succeeded because its arrival was timely. Since 2001, it has accumulated a base of articles—and a community of contributors—that cannot quickly be rivaled. No other multilingual reference sites have been created yet that could compete. Conceivably, criticisms noted in this chapter will lead to changes to the Wikipedia model or procedures and thus improve the encyclopedia, or a new site could improve Wikipedia's basic model. This idea is not impractical: The GFDL license and open ethos of Wikipedia explicitly encourage some kind of sequel to the site. And why shouldn't there be two tertiary sources for the planet, or even more? The future is wide open.

Notes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ See Umberto Eco, "The Force of Falsity," in Serendipities: Language and Lunacy, trans. William Weaver (New York: Columbia, 1998), 21.

- ↑ See Robert Collison, Encyclopedias: Their History Throughout the Ages (New York: Hafner, 1996), 21.

- ↑ For a critique of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, see Harvey Einbinder, The Myth of the Britannica (New York: Grove Press, 1964). This book by Einbinder, a physicist, is authoritative only for the mid-century editions of Encyclopaedia Britannica; it has a hostile bias, but it contains much interesting discussion and research on general tertiary source issues, such as updating, celebrity authors, science coverage, and humanistic approaches.

- ↑ See Jonathan Israel, Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity, 1650–1750 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 134.

- ↑ Israel, Radical Enlightenment, 135

- ↑ For a discussion of large-scale collaboration sympathetic to Linux, see James Surowiecki, The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many Are Smarter Than the Few and How Collective Wisdom Shapes Business, Economies, Societies and Nations (New York: Doubleday, 2004). For a history of GNU/Linux, see Glen Moody, Rebel Code: Inside Linux and the Open Source Revolution (New York: Basic Books, 2001).

- ↑ See the Definition of Free Cultural Works (http://freecontentdefinition.org/), which the Wikimedia Foundation adopted for its projects in 2007 (http://wikimediafoundation.org/wiki/Resolution:Licensing_policy).

- ↑ Alexa is a Web-traffic measuring company that uses data from individuals using the Alexa toolbar (http://www.alexa.com/).

- ↑ See John Seigenthaler, "A false Wikipedia 'biography,'" USA Today (November 29, 2005), http://www.usatoday.com/news/opinion/editorials/2005-11-29-wikipedia-edit_x.htm.

- ↑ The history of the whole incident is summarized in the article [[:w:Seigenthaler incident|]].

- ↑ See Noam Cohen, "A History Department Bans Citing Wikipedia as a Research Source," The New York Times (February 21, 2007), http://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/21/education/21wikipedia.html.

- ↑ The details of this restriction, from the first case in 2005, are posted at Wikipedia:Requests for arbitration/Climate change dispute. In the second case on the matter from 2005 (Wikipedia:Requests for arbitration/Climate change dispute 2), it was found that "William M. Connolley has generally adhered to his revert parole, although isolated instances can be found where compliance is incomplete or questionable," and "The one revert parole placed upon William M. Connolley was an unnecessary move, and is hereby revoked."

- ↑ See Jenny Kleeman, "Wikipedia Ban for Disruptive Professor," The Guardian (December 9, 2007), http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2007/dec/09/wikipedia.internet.

- ↑ The details of his case are posted at [[:w:Wikipedia:Requests for arbitration/Carl Hewitt|]]. Hewitt did not accept the justice of the rulings and attempted to circumvent the editing restrictions placed on him.

- ↑ See Stacy Schiff, "Know It All: Can Wikipedia Conquer Expertise?" The New Yorker (July 31, 2006), http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2006/07/31/060731fa_fact.

- ↑ See Andrew Keen, The Cult of the Amateur: How the Democratization of the Digital World is Assaulting Our Economy, Our Culture, and Our Values (New York: Doubleday, 2007). Keen's perspective is hostile to Wikipedia, emphasizing expertise and the impact on the encyclopedia business.

- ↑ See Don Tapscott and Anthony D. Williams, Wikinomics: How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything (New York: Penguin, 2006). Tapscott and Williams are sympathetic to Wikipedia, discussing it within a business context.

Summary

[edit | edit source]On March 15, 2007, a landmark was reached when the word wiki entered the Oxford English Dictionary Online, after the technology had existed for just under 12 years. Wikipedia's heritage stretches much further back, though, to the many early encyclopedia and knowledge-gathering projects of the ancient world and the impetus to understand the world during the Enlightenment era. In more recent times, the technological developments of the personal computer and the Internet made both wikis and Wikipedia possible, and the free software movement provided Wikipedia with its philosophical stance. This rich history has helped define Wikipedia's goals to provide free information to everyone in the world in their own language and to do so in a transparent, collaborative, dynamic, and open manner. Free software has also given Wikipedia its content license: the GFDL, which ensures that content will remain open, accessible, and freely reusable by anyone. These goals have been a part of Wikipedia since the site's beginnings in 2001. For all its idealism, however, the site has certainly not been immune to criticism of both the model itself and the implementation; in this chapter, we presented some case studies illustrating these criticisms.