Information and Communication Technologies for Poverty Alleviation/Print version

| This is the print version of Information and Communication Technologies for Poverty Alleviation You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

The current, editable version of this book is available in Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection, at

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Information_and_Communication_Technologies_for_Poverty_Alleviation

Preface

Preface to the First Edition

[edit | edit source]The information revolution is commonly talked about as a phenomenon that affects everybody, bringing fundamental changes to the way we work, entertain ourselves and interact with each other. Yet the reality is that for the most part, such changes have bypassed the majority of humankind, the billions of poor people for whom computers and the Internet mean nothing. However, in a growing number of instances, and as part of a quieter revolution, a variety of local organizations, aid agencies and government bodies are discovering that Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) can be used to extend the reach of the information revolution to the poorest of people living in the remotest corners of the world.

Under the right circumstances, ICTs have been shown to be capable of inducing social and economic development in terms of health care, improved education, employment, agriculture, and trade, and also of enriching local culture. Yet making this possible is by no means straightforward, as it involves more than the mere deployment of technology and requires as much learning on the part of the promoters of the technology as on the part of its users. It is all too easy to introduce technology with great expectations; it is far more challenging to create the necessary conditions under which the technology can attain its full potential, requiring as it does the combined and coordinated efforts of a range of stakeholders with disparate interests.

Much of the evidence in support of the use of ICTs for alleviating poverty remains anecdotal, and initiatives are proceeding with little reference to each other. There is a need for field practitioners to take stock of the experience that has so far been accumulated. Each experiment in the field generates learning opportunities and there are no failures, except perhaps our own when we do not learn from past experience. Moreover, as experience accumulates, we can begin to make general sense of it by detecting recurring themes and patterns of relationships that can be usefully carried forward.

This e-primer is brought to you by United Nations Development Programme Asia-Pacific Development Information Programme, in collaboration with the Government of India. APDIP seeks to create an ICT enabling environment through advocacy and policy reform in the Asia-Pacific region. The APDIP series of e-primers aims to provide readers with a clear understanding of the various terminologies, definitions, trends and issues associated with the information age. This e-primer on ICTs for Poverty Alleviation reviews contemporary initiatives at field level and synthesizes the learning opportunities that they provide. It serves as a practical guide for field implementers, offering not only a glimpse of best practices, but also a deeper understanding of how these have been applied in a range of instances.

We wish to acknowledge the contribution of the peer reviewers and the production team of the e-primer series.

| Shahid Akhtar Programme Coordinator, |

O.P.Agarwal Joint Secretary (Training), |

Introduction

The major aid agencies and donors, as well as many developing country governments, are becoming increasingly enthusiastic about the prospects for improving the effectiveness of their development activities by making Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) available to poor people. This primer describes how ICTs are being used to alleviate poverty. It addresses the so-called digital divide, which describes the stark disparities between the few people with abundant access to ICTs and the vast numbers of people without any access at all, and describes the efforts that are being applied to overcome it.

INTRODUCTION

[edit | edit source]Information and knowledge are critical components of poverty alleviation strategies, and ICTs offer the promise of easy access to huge amounts of information useful for the poor. However, the digital divide is argued to be the result rather than the cause of poverty, and efforts to bridge it must be embedded within effective strategies that address the causes of poverty. Moreover, earlier patterns of adoption and diffusion of technology suggest that ICTs will not achieve their full potential without suitable attention being paid to the wider processes that they are intended to assist and to the context within which they are being implemented.

There are many examples of successful implementation that allow for a synthesis of experience that can lead to an understanding of how to approach the use of ICTs for widespread alleviation of poverty.

ICTs are usually understood to refer to computers and the Internet, but many consider this view to be limited, as it excludes the more traditional and usually more common technologies of radio, television, telephones, public address systems, and even newspapers, which also carry information. In particular, the potential value of radio as a purveyor of development information should not be overlooked, especially in view of its almost ubiquitous presence in developing countries, including the rural locations in which the vast majority of the poor live.

This primer describes several examples of how ICTs have contributed to poverty alleviation, to a greater or lesser extent. Several case studies are given at the end. Some lessons learned from the examples are synthesized and it is shown how implementation efforts have to take into account the wide variety of factors that are critical for success. A poverty alleviation framework is presented to facilitate the full consideration of all such factors and the framework is used to analyse the outcomes of the cases and the factors that have influenced them.

Many of the factors that will define how ICTs will be integrated into existing community and national development initiatives are highly contextual in nature; dependent on existing norms of institutional behaviour and on how vigorously reforms can be implemented. As a result, diffusion and replication rates will vary among communities and between nations. In some cases, we can expect slow progress towards further diffusion of ICTs for poverty alleviation.

Concepts & Definitions

What is poverty, where is it, and how does it look when it has been alleviated?

[edit | edit source]Before examining how ICTs might be used to alleviate poverty, it is appropriate to consider what is actually meant by poverty. The World Bank reports that of the world’s six billion people, 2.8 billion, almost half, live on less than US$2 a day, and 1.2 billion, a fifth, live on less than US$1 a day, with 44 percent of them living in South Asia. The Millennium Development Goals set for 2015 by international development agencies include reducing by half the proportion of people living in extreme income poverty, or those living on less than US$1 a day. The figure of US$1 income per day is widely accepted as a general indicator of extreme poverty within development discourse, but of course there is no absolute cut-off and income is only one indicator of the results of poverty, among many others.

Figure 1: Indicates the Global Distribution of Poverty (World Bank, 2001/2002)

|

This image is available under the terms of GNU Free Documentation License and Creative Commons Attribution License 2.5

The World Bank report goes beyond the view of income levels in its definition of poverty, suggesting that poverty includes powerlessness, voicelessness, vulnerability, and fear. Additionally, the European Commission suggests that poverty should not be defined merely as a lack of income and financial resources. It should also include the deprivation of basic capabilities and lack of access to education, health, natural resources, employment, land and credit, political participation, services, and infrastructure (European Commission, 2001). An even broader definition of poverty sees it as being deprived of the information needed to participate in the wider society, at the local, national or global level (ZEF, 2002).

The assertion that a knowledge gap is an important determinant of persistent poverty, combined with the notion that developed countries already possess the knowledge required to assure a universally adequate standard of living, suggest the need for policies that encourage greater communication and information flows both within and between countries. One of the best possible ways to achieve this greater interaction is through the use of ICTs. But when this happens, how is it possible to measure the effects?

Increases in household income that can be directly attributed to the use of ICTs are probably easy to isolate with careful research. Changes in the other characteristics of poverty, such as voicelessness and vulnerability, will be harder to tease out with research, and are best detected by asking the people concerned directly.

Experiences with field evaluations of ICTs that were deployed to alleviate poverty have been mixed and are controversial. Pilot projects have often failed to deliver expected benefits quickly enough for their funding agencies, or they have delivered unexpected benefits that the evaluators have difficulty accounting for. Usually, the time scales that communities require to fully appropriate ICTs and to use them to achieve significant benefits far exceed the expectations of the technology promoters and/or evaluators, who run out of patience and prematurely and inappropriately declare the project a failure.

What is the “digital divide”?

[edit | edit source]The uneven global distribution of access to the Internet has highlighted a digital divide that separates individuals who are able to access computers and the Internet from those who have no opportunity to do so. Kofi Annan, Secretary-General of the United Nations, has said:

- The new information and communications technologies are among the driving forces of globalisation. They are bringing people together, and bringing decision makers unprecedented new tools for development. At the same time, however, the gap between information ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’ is widening, and there is a real danger that the world’s poor will be excluded from the emerging knowledge-based global economy. (Anan, 2002)

A few statistics serve to highlight the alarming differences between those at both ends of the digital divide:

- All of the developing countries of the world own a mere four percent of the world’s computers.

- 75 percent of the world’s 700 million telephone sets can be found in the nine richest countries.

- There are more web hosts in New York than in continental Africa; there are more in Finland than in Latin America and the Caribbean combined.

- There were only 6.3 million Internet subscribers on the entire African continent in September 2002 compared with 34.3 million in the UK. (Nua Internet)

Table 1 shows the gap in Internet access between the industrialized and developing worlds. More than 85 percent of the world’s Internet users are in developed countries, which account for only about 22 percent of the world’s population.

Figure 2

|

Looking more closely at the access statistics reveals further levels of inequality within the developing countries that are least served. Typically, a high percentage of developing country residents live in rural areas. The proportion can rise to as much as 85 percent of the population in the least developed countries and is estimated at 75 percent overall in Asia. Rural access to communication networks in developing countries is much more limited than in urban areas. Table 2 depicts global teledensity levels (main lines plus cellular subscribers), indicating that the USA has more telephones than people, whereas Africa has a mere 6.6 telephones per 100 inhabitants.

In developing countries, rural teledensity is even lower than the global figures might suggest because of the differences between them and their urban counterparts. In the poorest countries, the already low urban teledensity can be three times or more that of the rural areas, whereas in the richest countries it is about the same. Table 3 shows how Internet host and personal computers are distributed throughout the world, further highlighting the gaps between developed and developing nations.

Figure 3

|

Not surprisingly, the digital divide mirrors divides in other resources that have a more insidious effect, such as the disparities in access to education, health care, capital, shelter, employment, clean water and food. These other divides can arguably be viewed as being a result of an imbalance in access to information— in short, the digital divide—than its cause. Information is critical to the social and economic activities that comprise the development process. Thus, ICTs, as a means of sharing information, are a link in the chain of the development process itself (ILO, 2001).

Figure 4

|

Does the digital divide refer only to access to technology?

[edit | edit source]Eliminating the digital divide requires more than the provision of access to technologies. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), although ICTs can contribute significantly to socio-economic development, investments in them alone are not sufficient for development to occur (ILO, 2001). Put simply, telecommunications is a necessary but insufficient condition for economic development (Schmandt et. al, 1990).

Martin and McKeown suggest that the application of ICTs is not sufficient to address problems of rural areas without adherence to principles of integrated rural development. Unless there is at least minimal infrastructure development in transport, education, health, and social and cultural facilities, it is unlikely that investments from ICTs alone will enable rural areas to cross the threshold from decline to growth (Martin and McKeown, 1993).

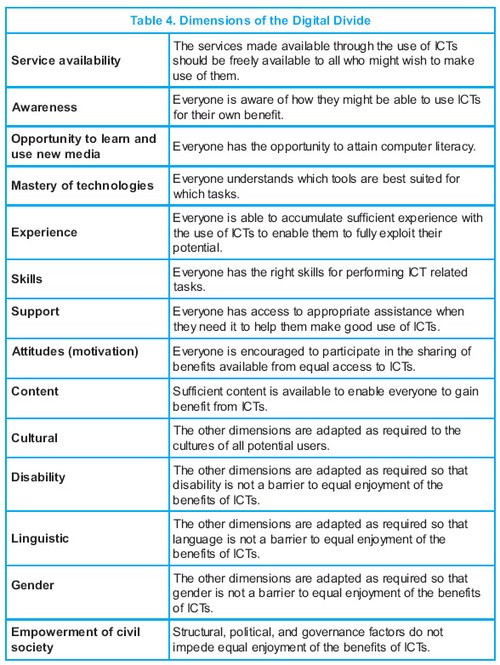

The digital divide then goes beyond access to the technology and can be expressed in terms of multiple dimensions. And if societies wish to share the benefits of access to technology, then further provisions have to be made in order to address all of the dimensions of the digital divide. Table 4 summarizes these dimensions.

These dimensions of the digital divide imply a variety of societal concerns that have to do with education and capacity building, social equity, including gender equity, and the appropriateness of technology and information to its socio-economic context.

Figure 5

|

Furthermore, some consider even the use of the term “digital divide” to be problematic. First, it is not the real issue; it is the information and knowledge gap that is the real concern and in that regard, the multiple dimensions in Table 4 deserve equal attention. Second, talk of a digital divide often implies that digital access alone will overcome the associated problems. Digital access requires only purchase and installation of technology. In fact, the multiple dimensions of the digital divide imply that it is not money and technology that matter but the right approach, and unless the other divides are also addressed, crossing the digital bridge will not achieve much. Finally, and possibly more significant, is an understanding of the patterns of cause and effect. As the G8 DOT Force report points out, the digital divide is a reflection of existing broader socio-economic inequalities, and a symptom of much more profound and long-standing economic and social divides within and between societies. The report goes on: “There is no dichotomy between the ‘digital divide’ and the broader social and economic divides which the development process should address; the digital divide needs to be understood and addressed in the context of those broader divides.” (G8 DOT Force, 2001).

The argument seems to be that the digital divide is the result rather than the cause of poverty, and that efforts to “bridge the digital divide” and increase access to ICTs, unless clearly rooted in, and subordinate to, a broader strategy to combat poverty, risk diverting attention and resources from addressing its underlying causes, such as unfair trade policies, corruption, bad governance and so on. In the next section, we examine the crucial aspect of how ICTs should be embedded within strategies for combating poverty so that both (the ICTs and the strategies) can achieve their optimal effect.

What information technologies are capable of alleviating poverty?

[edit | edit source]In this section we will discuss the following ICTs: radio, television, telephones, public address systems, and computers and the Internet.

Radio

Radio has achieved impressive results in the delivery of useful information to poor people. One of its strengths is its ubiquity. For example, a recent survey of 15 hill villages in Nepal found radios in every village, with farmers listening to them while working in their fields. Another survey of 21,000 farmers enrolled in radio-backed farm forums in Zambia found that 90 percent found programmes relevant and more than 50 percent credited the programmes and forums with increasing their crop yields (Dodds, 1999). In the Philippines, a partnership programme between UNESCO, the Danish International Development Agency and the Philippine government is providing local radio equipment and training to a number of remote villages. The project is designed to ensure that programming initiatives and content originate within the communities. According to UNESCO, the project has not only increased local business and agricultural productivity, but also resulted in the formation of civic organizations and more constructive dialogue with local officials (UNESCO Courier 1997).

In South Africa, clockwork radios that do not require battery or mains electricity supplies are being distributed to villages to enable them to listen to development programming. The Baygen Freeplay radio marks one of the first commercially successful communication devices to employ a clockwork mechanism as its power supply. It is sold on a commercial basis for approximately US$75 and has been used extensively by a number of non-governmental organizations as a key element in community education programmes and disaster relief efforts. For instance, the National Institute for Disaster Management in Mozambique distributed Freeplay radios so that flood victims could receive broadcasts on the weather, health issues, government policy toward the displaced, missing family members, the activities of the aid community, and the location of land mines. In Ghana, the government distributed 30,000 Freeplay radios so villagers could follow elections.

In Nepal, a digital broadcast initiative is being tested that will broadcast digital radio programming via satellite to low-cost receivers in rural and remote villagers. The programme is targeting HIV/AIDS awareness, and has the potential to link with computers to receive multimedia content.

Community radio projects indicate how communities can appropriate ICTs for their own purposes. For example, in Nepal, two community radio stations are well established—Radio Lumbini in Manigram in western Nepal and Radio Madan Pokhara in Palpa District. The Village Development Committee holds one licence and a community group holds the other. Both services have proven to be very popular. Ownership of radio receivers in the coverage areas has increased dramatically (shown as 68 percent in the census). Programmes include valuable development messages, such as AIDS awareness and prevention. The Kothmale community radio station in Sri Lanka [1] accepts requests for information from community members and searches the Internet for answers, which it then broadcasts on the air.

Television

Television is commonly cited as having considerable development potential, and some examples of using it for education are given later in the report. Probably the most notable example of TV for development comes from China with its TV University and agricultural TV station. In Viêt Nam, two universities in the Mekong Delta Region work with the local TV station to broadcast weekly farmers workshops that are watched by millions.

Telephone

The well-known case of Grameen hand phones in Bangladesh, in which the Grameen Bank, the village-based micro-finance organization, leases cellular mobile phones to successful members, has delivered significant benefits to the poor. The phones are mostly used for exchanging price and business and health-related information. They have generated information flows that have resulted in better prices for outputs and inputs, easier job searches, reduced mortality rates for livestock and poultry, and better returns on foreign-exchange transactions. Phone owners also earn additional income from providing phone services to others in the community. Poor people account for one-fourth of all the phone calls made. For villagers in general, the phones offer additional non-economic benefits such as improved law enforcement, reduced inequality, more rapid and effective communication during disasters and stronger kinship bonding. The phones also have perceptible and positive effects on the empowerment and social status of phone-leasing women and their households (Bayes et al., 1999).

A study in China found that villages that had the telephone, the most basic communications technology, experienced declines in the purchase price of various commodities and lower future price variability. It also noted that the average prices of agricultural commodities were higher in villages with phones than in villages without phones. Vegetable growers said that access to telephones helped them to make more appropriate production decisions, and users of agricultural inputs benefited from a smoother and more reliable supply. Better information also improved some sellers’ perception of their bargaining position vis-à-vis traders or intermediaries. Finally, village telephones facilitated job searches, access to emergency medical care and the ability to deal with natural disasters; lowered mortality rates for livestock thanks to more timely advice from extension workers; and improved rates in foreign-exchange transactions (Eggleston et al., 2002).

Public address systems

Public address systems are commonly found in China and Viêt Nam where they are used to deliver public information, announcements and the daily news. One community in Viêt Nam is planning to augment its public address system by connecting to the Internet to obtain more useful information for broadcasting. Public address systems are more localized than radio, but are technically simpler and less expensive. However, research on poor communities suggests that the telephone and radio remain the most important (direct access) ICT tools for changing the lives of the poor (Heeks, 1999).

Computers and the Internet

Computers and the Internet are commonly made available to poor communities in the form of community-based telecentres. As the examples cited in this report and the case studies in the annex show, community-based telecentres provide shared access to computers and the Internet and are the only realistic means of doing this for poor communities. Although telecentres come in many guises, the two key elements are public access and a development orientation. It is the latter characteristic that distinguishes telecentres from cyber cafés. Of course, the cyber café can be a useful device in fostering development through ICTs, but the difference is crucial, because development-oriented telecentres embody the principle of providing access for a purpose—that of implementing a development agenda.

To achieve their development objectives, telecentres perform community outreach services in order to determine the types of information that can be used to foster development activities. Computer literate telecentre staff act as intermediaries between community members who may not be familiar with ICTs and the information services that they require. Telecentres can provide a range of ICT-based services from which they can earn an income, such as telephone use, photocopying and printing, email and word processing. This helps with financial self-sustainability, which telecentres are often required to attain, although some argue that ICT-based development services should not have to be paid for by poor people, and should be provided as a public service, rather like libraries. The results of experiments with telecentres are mixed: some have demonstrated considerable benefits for their target audiences; others are struggling with fragile connectivity and uncertain communities. Very few have achieved self-financing sustainability.

Development Strategies and ICTs

What is the relationship between development, information and ICTs?

[edit | edit source]There is a risk that the argument in support of ICTs for development will be used excessively, in support of projects that cannot otherwise be justified by more rational means. The attendant danger is that the concept of ICTs for poverty alleviation loses credibility among development planners and decision makers. Nevertheless, the potential of information as a strategic development resource should be incorporated as a routine element into the development planning process, so that project managers become used to thinking in these new terms.

The most effective route to achieving substantial benefit with ICTs in development programmes is to concentrate on re-thinking development activities by analysing current problems and associated contextual conditions, and considering ICT as just one ingredient of the solution. This implies an approach to developing strategies for information systems and technology that are derived from and integrated with other components of the overall development strategy. This approach is depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6. The Relationship Between Development, Information and ICTs

|

The general rule is that the application of ICTs to development should always begin with a development strategy. From that, an information plan for implementing the development strategy can be derived and only out of that should come a technology plan. While strategic thinking can be informed by an appreciation of the capabilities of ICTs, it is essential to have clear development targets that are specific to the context before the form of use of the ICTs is defined. Additionally, in considering the development strategy, bottom-up, demand-driven development objectives are usually preferable to top-down, supply-driven objectives, so that goals begin with an appreciation of the needs of development recipients as they would themselves express them.

From an unambiguous articulation of the development strategy, an information plan is drawn. This will set down the information resources required to achieve the development strategy. Again, this determination can be made against an informed background with regard to the capabilities of ICTs, but it should not be driven by the mere application of technology. Finally, a plan for the technology can be drawn up that will be capable of delivering the information resources required for the achievement of the strategy.

Although such an approach makes sense intuitively, there are many examples of technology-related development projects that are technology-driven, top-down and supply-driven, and they often result in sub-optimal outcomes because of this.

Modelling the relationship between ICTs and development addresses the earlier comments about the digital divide in greater depth. The model is applicable at all points at which closing the divide is attempted. It was developed to facilitate a grass-roots implementation targeting community development where heavy emphasis was placed on empowering the community to construct their own agenda for ICT-assisted development, prior to introducing the technology (Harris et al., 2001).

In the next section, a number of technology-related development initiatives are described, and the reader might wish to reflect on the extent to which the outcomes of each were a result of deploying technology or of implementing a sound development strategy. The earlier discussion of some of the technology choices available underscores the need to be clear about the development and information delivery strategies before deciding on the technology. In highlighting where such strategies may be applied, subsequent sections provide a brief overview of the major areas of application of ICTs to poverty alleviation that have been observed to offer some promise.

What strategies for poverty alleviation have been successfully pursued with the use of ICTs?

[edit | edit source]Distributing locally relevant information

In the case of Internet diffusion, a consistent finding of surveys of Internet users and providers in developing countries is that the lack of local language and locally relevant content is a major barrier to increased use. Unless there is a concerted effort to overcome this constraint, Internet growth in many developing countries could be stuck in a low-use equilibrium (Kenny et al., 2001). The undersupply of pro-poor local content inhibits the virtuous circle, known as the network effect, whereby the growth of the on-line community makes the development of Internet content a more attractive commercial and social proposition, and increasing amounts of attractive content encourages the growth of the on-line community.

In the Village Information Shops in Pondicherry, India, a major contributory factor to all operations is the use of Tamil language and Tamil script in the computers (Sentilkumaran and Arunachalam, 2002). Despite there being no standard for the representation of Tamil in software at the time of implementation, the project staff were able to develop the use of Microsoft Office applications in Tamil script. Moreover, the applications are operated in Tamil using a western, Roman script QWERTY keyboard. The operators (semi-literate women) have learned the appropriate keyboard codes for the Tamil characters and are quite proficient at data entry. The centre in Villianur has generated a number of databases for local use, and all but one are in Tamil. The centres collect information on indigenous knowledge systems and are developing useful brochures in Tamil.

Beyond the entry of data, the extent to which use of the Tamil language has promoted the use of the information shops and fostered interactivity and engagement between the various information systems that are available and their intended beneficiaries, cannot be underestimated. Local content is directed towards the information needed to satisfy the communities’ needs, and is developed in collaboration with the local people. There are close to a hundred databases, including rural yellow pages, which are updated as often as needed. An entitlements database serves as a single-window for the entire range of government programmes, fostering greater transparency in government. Relevant content is obtained from elsewhere if it is found useful to the local community. For example, useful information has been collected from Government departments, the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Aravind Eye Hospital and the US Navy’s web site. The centres have held health camps in the villages in cooperation with local hospitals as part of gathering information about local health care needs. The centres use multimedia and loud speakers to reach out to illiterate clients, and publish a fortnightly Tamil newspaper called Namma Ooru Seithi (Our Village News), which has become so popular that Government departments such as the District Rural Development Agency, Social Welfare Board, and the Small Scale Industries Centre use it to publicize their schemes (Arunachalam, 2002).

The Gyandoot project in Madhya Pradesh State of India is an intranet in the district of Dhar that connects rural cyber cafés catering to the everyday needs of the masses [2] . It provides the following services:

- Commodity marketing information system

- Income certificate

- Domicile certificate

- Caste certificate

- Landholder’s passbook of land rights and loans

- Rural Hindi e-mail

- Public grievance redressal

- Forms of various government schemes.

- Below-Poverty-Line Family List

- Employment news

- Rural matrimonial

- Rural market

- Rural newspaper

- Advisory module

- E-education

Targeting disadvantaged and marginalized groups

Within populations of poor people, disadvantaged and marginalized sections of society usually face impediments to using, and making good use of, ICTs in much the same way that they might face impediments in using other resources. Women in developing countries in particular face difficulties in using ICTs, as they tend to be poorer, face greater social constraints, and are less likely to be educated or literate than men. Moreover, they are likely to use ICTs in different ways, and have different information requirements than men. Women are also less likely to be able to pay for access to ICTs, either because of an absolute lack of funds or because they lack control of household expenditure. Constraints on women’s time or their movement outside of the home can also reduce their ability to access technologies (Marker et al. 2002). Such groups usually require special assistance and attention in order to benefit from programmes that are targeted at poor people.

People who do not understand the English language are also a marginalized section of society on the Internet. Such people include the majority populations of French-speaking Africa, the Middle East, Eastern Europe and Latin America. Even when users have basic English proficiency, they are discouraged from using web sites that are only in English.

Strategies for reaching marginalized sectors of society through ICTs include the collection, classification, protection, and commercialization of indigenous knowledge by minority groups using ICTs. Traditional remedies are being recorded in databases and afforded protection from foreign applications for patents. The value of such practices is evident from the stringent rules imposed by the state government of Sarawak, Malaysia, on the island of Borneo, over the collection of flora samples in their rainforests, where a particular tree species promises to yield substances that might lead to a cure for HIV/AIDS. The Honey Bee network in India collects local innovations, inventions and remedies, stores them on-line, and helps owners obtain incomes from local patents and commercialization of inventions. The database contains more than 1,300 innovations. Similarly, the Kelabit ethnic group of Sarawak, one of Borneo’s smaller ethnic minorities, are recording their oral history in a database of stories told by the old people. They are also using computers to assemble their genealogical records.

The selling of handicrafts on the Internet by local artisans, a form of e-commerce, also provides buyers with the historical and cultural background of indigenous products. Traders in such products deliberately disconnect ethnic artefacts from the identity of the artists in order to keep down the prices at which they can obtain the artists’ works. Providing the artisans with more direct access to their market through the Internet allows them to build up a clientele and achieve recognition as the creator of original art and crafts. Relatedly, web sites that feature aboriginal art can now be found with strict warnings against using Australian aboriginal designs without permission, seemingly in response to complaints that T-shirt manufacturers freely plagiarize designs without any recompense to the creators. Whether such warnings are effective is hard to tell, but at least the web site can be used to register ownership rights and to demonstrate priority in the creation of designs.

Nearly 80 percent of the world’s disabled population of 500 million people lives in developing countries. Usually their disability only compounds the difficulties they already face as (possibly poor) citizens of developing countries. But like people who live in isolated and remote locations, they probably stand to gain far more benefit from being able to make good use of ICTs. Efforts to enable access to ICTs by disabled people are under way. One such effort relates to the development of adaptive technology, which is a major prerequisite for many people with disabilities to use computer technology. These are modifications or upgrades to a computer’s hardware and software to provide alternative methods of entering and receiving data. Many of the modifications can be made relatively inexpensively. Some modifications can be as simple as lowering a computer desk while others can be as elaborate as attaching an input device that tracks eye movements. Common adaptive technologies include programs that read or describe the information on the screen, programs that enlarge or change the colour of screen information, and special pointing or input devices. There are standards and guidelines for World Wide Web accessibility and electronic document accessibility for individuals with disabilities. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines set out by the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) [3] is the world standard for WWW contents accessibility.

Digital Divide Data Entry is a philanthropic organization that uses the Internet, the English language and the computer skills of Cambodia’s youth to provide basic information services to North America corporations. They employ 10 disabled people to copy type documents into a computer, a simple task that requires only typing skills and a basic knowledge of English. The organization is currently working on a US$30,000 contract to input more than 100 years of archives of the Harvard University newspaper. Once completed, the work can be sent to the US via e-mail. There are plans to hire more disabled people, more women and more poor people, and to expand from data entry to more complicated tasks, like creating web pages and Power Point presentations.

Promoting local entrepreneurship

It has been claimed that ICTs have the potential to impact the livelihood strategies of small-scale enterprises and local entrepreneurs in the following areas:

- Natural capital - opportunities for accessing national government policies

- Financial capital - communication with lending organizations, e.g., for micro-credit

- Human capital - increased knowledge of new skills through distance learning and processes required for certification

- Social capital - cultivating contacts beyond the immediate community

- Physical capital - lobbying for the provision of basic infrastructure

To cite an example, India Shop is an Internet-based virtual shopping mall selling Indian handicrafts. Established by the Foundation of Occupational Development (FOOD) in Chennai, India Shop involves e-marketers who promote the goods over the Internet, through chat-rooms and mail lists. They work from a computer, either at home or in a cyber café, and draw commissions on the sales that they achieve. The e-marketers respond to sales enquiries and liase with the craftspeople, typically exchanging multiple e-mails with clients before sales are closed. There are more than 100 people marketers, earning between Rs2,000Rs10,000 per month.

In Gujarat, computerized milk collection centres using embedded chip technology are helping ensure fair prices for small farmers who sell milk to dairy cooperatives. The fat content of milk used to be calculated hours after the milk was received; farmers were paid every 10 days and had to trust the manual calculations of milk quality and quantity made by the staff of cooperatives. Farmers often claimed that the old system resulted in malfeasance and underpayments, but such charges were difficult to prove. Computerized milk collection now increases transparency, expedites processing, and provides immediate payments to farmers (World Bank, 2002).

Indeed, small-scale entrepreneurs in developing countries, especially women, have shown the ability to harness ICTs for developing their enterprises. For example, a group of ladies in Kizhur village, Pondicherry decided that they wanted to start a small business enterprise manufacturing incense sticks. They began as sub-contractors but their confidence and enterprise grew from utilizing the local telecentre. As a result of some searches by the telecentre operators, they were able to develop the necessary skills for packaging and marketing their own brand name incense. The ladies were quickly able to develop local outlets for their products and they are confidently using the telecentre to seek out more distant customers.

ICT and e-commerce are attractive to women entrepreneurs (who in many developing countries account for the majority of small and medium-size enterprise owners), as it allows them to save time and money while trying to reach out to new clients in domestic and foreign markets. There are many success stories in business-to-consumer (B2C) retailing or e-tailing from all developing-country regions, demonstrating how women have used the Internet to expand their customer base in foreign markets while at the same time being able to combine family responsibilities with lucrative work. However, in spite of the publicity given to e-tailing, its scope and spread in the poorer parts of the world have remained small, and women working in micro-enterprises and the informal sector are far from being in a position to access and make use of the new technologies. Moreover, B2C e-commerce is small compared to business-to-business (B2B) e-commerce and thus benefits only a small number of women (UNCTAD, 2002).

Improving poor people’s health

Health care is one of the most promising areas for poverty alleviation with ICTs, based largely as it is on information resources and knowledge. There are many ways in which ICTs can be applied to achieve desirable health outcomes. ICTs are being used in developing countries to facilitate remote consultation, diagnosis, and treatment. Thus, physicians in remote locations can take advantage of the professional skills and experiences of colleagues and collaborating institutions (DOI, 2001). Health workers in developing countries are accessing relevant medical training through ICT-enabled delivery mechanisms. Several new malaria Internet sites for health professionals include innovative “teach-and-test” self-assessment modules. In addition, centralized data repositories connected to ICT networks enable remote health care professionals to keep abreast of the rapidly evolving stock of medical knowledge.

When applied to disease prevention and epidemic response efforts, ICT can provide considerable benefits and capabilities. Public broadcast media such as radio and television have a long history of effectively facilitating the dissemination of public health messages and disease prevention techniques in developing countries. The Internet can also be utilized to improve disease prevention by enabling more effective monitoring and response mechanisms.

The World Health Organization and the world’s six biggest medical journal publishers are providing access to vital scientific information to close to 100 developing countries that otherwise could not afford such information. The arrangement makes available through the Internet, for free or at reduced rates, almost 1,000 of the world’s leading medical and scientific journals to medical schools and research institutions in developing countries. Previously, biomedical journal subscriptions, both electronic and print, were priced uniformly for medical schools, research centres and similar institutions, regardless of geographical location. Annual subscription prices cost on average several hundred dollars per title. Many key titles cost more than US$1500 per year, making it all but impossible for the large majority of health and research institutions in the poorest countries to access critical scientific information.

Apollo Hospitals has set up a telemedicine centre at Aragonda in Andhra Pradesh, to offer medical advice to the rural population using ICTs. The centre links healthcare specialists with remote clinics, hospitals, and primary care physicians to facilitate medical diagnosis and treatment. The rural telemedicine centre caters to the 50,000 people living in Aragonda and the surrounding six villages. As part of the project, the group has constructed in the village a 50-bed multi-speciality hospital with a CT scan, X-ray, eight-bed intensive care unit, and blood bank. It also has equipment to scan, convert and send data images to the tele-consultant stations at Chennai and Hyderabad. The centre provides free health screening camps for detection of a variety of diseases. There is a VSAT facility at Aragonda for connectivity to Hyderabad and Chennai. The scheme is available to all the families in the villages at a cost of Rs.1 per day for a family of five.

In Ginnack, a remote island village on the Gambia River, nurses use a digital camera to take pictures of symptoms for examination by a doctor in a nearby town. The physician can send the pictures over the Internet to a medical institute in the UK for further evaluation. X-ray images can also be compressed and sent through existing telecommunications networks.

Across Sub-Saharan Africa, the Internet is used to report daily cases of meningitis to monitor emerging epidemics. When threshold levels are reached, mass vaccination is required and the Internet is used to rapidly mobilize medical personnel and effectively coordinate laboratories and specialist services.

In Andhra Pradesh again, handheld computers are enabling auxiliary nurse midwives to eliminate redundant paperwork and data entry, freeing time to deliver health care to poor people. Midwives provide most health services in the state’s vast rural areas, with each serving about 5,000 people, typically across multiple villages and hamlets. They administer immunizations, offer advice on family planning, educate people on mother-child health programs and collect data on birth and immunization rates. Midwives usually spend 15–20 days a month collecting and registering data. But with handheld computers they can cut that time by up to 40 percent, increasing the impact and reach of limited resources (World Bank, 2002).

Strengthening education

The growth of distance education is being fuelled by the urgent need to close the education gap between poor and rich nations. According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), only about three percent of young people in sub-Saharan Africa and seven percent in Asia attend some form of postsecondary education. This compares with 58 percent in industrialized countries as a whole, and 81 percent in the United States.

Developing countries see investing in distance education programmes as a way to educate more people for less money. UNESCO and the World Bank have reported that in the world’s 10 biggest distance education institutions, the majority of which are in the Third World, the cost of education per student is on average about one third the cost at traditional institutions in the same country. In China, where only one out of 20 young people receives higher education, distance learning is helping the education system move from elite to mass education because traditional universities cannot meet the demand. China Central Radio and Television University has 1.5 million students, two-thirds of them in degree programmes. The university caters to working adults. It broadcasts radio and TV lectures at fixed times to students at 2,600 branch campuses and 29,000 study centres, as well as at workplaces.

Distance education seems a natural pre-cursor to on-line education, but the two are not the same, and the transition from the former to the latter can be a challenge. Even the pioneering British Open University still bases its course work on hard copy material, using the Internet for the support aspects of education, such as student and tutor interaction. Initial enthusiasm for the idea of a virtual university has been slow to materialize and there are still very few fully accredited degree programmes that can be taken entirely on-line. Some of the difficulties arose from the slow emergence of understanding about what ICTs contribute to the pedagogical aspects of the teaching-learning process. Other barriers to e-learning include the time and cost required to prepare digital learning materials.

On-line distance education is better suited to adult learners and there are now many organizations opening virtual universities to cater for them. The element of flexible timing for learning appeals to adults who are employed and who realize the value of life-long learning in a changing work environment.

Most developments in e-learning benefit the already privileged. Nevertheless, examples of pro-poor learning indicate the possibilities for the less privileged. It is almost a universally observable phenomenon that children seem to take to computers naturally, and in a unique experiment in India, this has been turned into a new mode of education called minimally invasive education. In 1999, Sugata Mitra of NIIT Ltd. placed an Internet-capable personal computer behind a glass screen in a wall of his office building that looked out to a piece of land occupied by street kids. In what became known as the “Hole in the Wall” experiment, the children very quickly learned an impressive range of computer skills without any tuition at all. As one child learned something new from experimentation, he/she passed it on to the next child. The experiment has since been repeated in half a dozen locations, and Mitra is making plans for 100,000 kiosks to create 100 million computer literates in five years.

In primary and secondary education, radio and television are increasingly important means of reaching the rural poor. In Mexico, over 700,000 secondary-school students in remote villages now have access to the Telesecundaria program, which provides televised classes and a comprehensive curriculum through closed-circuit television, satellite transmissions and teleconferencing between students and teachers. Studies have found that the program is only 16 percent more expensive per pupil served than normal urban secondary schools, while students benefit from the much smaller student-to-teacher ratios. Rural students enter the program with substantially lower mathematics and language test scores than their counterparts at traditional urban schools, but by graduation, they have equalled the math scores of those in the urban schools and cut the language score deficit in half (de Moura et al. 1999).

Further evidence that the impact of the Internet need not be limited to higher education or wealthier students can be found in Brazil’s urban slums. The Committee to Democratise Information Technology (CDI) has created 110 sustainable and self-managed community-based Computer Science and Citizenship Schools using recycled technology, volunteer assistance and very limited funds. CDI schools train more than 25,000 young students every year in ICT skills that give them better opportunities for jobs, education and life changes. CDI also provides social education on human rights, non-violence, the environment and health and sexuality. CDI cites many cases of participants developing renewed interest in formal schooling, resisting the lure to join drug gangs, and greatly increasing their self-esteem. Also, many of the program’s graduates are putting their computer skills to work in various community activities, including health education and AIDS awareness campaigns. Most teachers in CDI schools are themselves graduates of the program who have embraced technology and want to continue CDI’s work in their own communities (InfoDev).

Promoting trade and e-commerce

It is in the Asia Pacific region that e-commerce is spreading most quickly among developing countries. The region’s enterprises, particularly in manufacturing, are exposed to pressure from customers in developed countries to adopt e-business methods and are investing to be able to do so. China’s population of Internet users is already the world’s third largest.

M-commerce, defined as the buying and selling of goods and services using wireless handheld devices such as mobile telephones or personal data assistants (PDAs), is likewise growing at a rapid pace. In the last four years, growth in the number of mobile telephone users worldwide has exceeded fixed lines, expanding from 50 million to almost one billion in 2002. This rapid growth stems from the cost advantage of mobile infrastructure over fixed-line installation and from the fact that mobile network consumers can simply buy a handset and a prepaid card and start using it as soon as the first base stations are in place, without having to open a post-paid account. The introduction of wireless communications has also brought wireless data services, which are essential to conducting m-commerce, to many developing countries. If the convergence of mobile and fixed Internet and ICTs continues, first access to the Internet for a significant part of the world will be achieved using mobile handsets and networks. Wireless technologies have made inroads even in relatively low-income areas, where prepaid cards allow access to people who cannot take out a subscription because of billing or creditworthiness problems. Developing Asia is the leader in this area (UNCTAD 2002).

The main areas of m-commerce use are in text messaging or SMS (short messaging service), micro-payments, financial services, logistics, information services and wireless customer relationship management. Text messaging has been the most successful m-commerce application in developing countries, where rates of low fixed-line connectivity and Internet access have made it an e-mail surrogate. Operators in China and other Asian developing countries are gearing up for m-commerce applications for financial services in particular. However, difficulties in making electronic payments and concerns over the security and privacy of transactions are limiting the conduct of m-commerce. It may have to wait for third-generation wireless technologies and fully Internet-enabled handsets.

ICTs have been widely touted as windows to global markets for small-scale developing country producers. However, there are significant barriers facing artisans in the developing world who are trading directly with consumers (business to consumer) via the Internet. Apart from anecdotal stories, there is little evidence of craft groups successfully dealing direct with end consumers on a sustainable basis. Business-to-business e-commerce offers the greatest opportunities for artisan groups to enhance the service given to business customers (exporters, importers, alternative trade organizations, wholesale and retail buyers etc). This is likely to be much more fruitful and cost-effective for artisans.

PEOPLink is a non-profit organization that has been equipping and training grass-roots artisan organizations all over the world to use digital cameras and the Internet to market their wares while showcasing their cultural richness [4] . Between 1996 and 2000, PEOPLink developed training modules and used them as the basis for on-site workshops and on-line support for web catalogue development by 55 trading partners serving more than 100,000 artisans in 22 countries. PEOPLink offers a tool-kit to communities that enable them to create a digital catalogue of their handicrafts for posting onto a web site. It also provides additional services such as on-line trend reports, product development and feedback tools, as well as providing logistical support and services such as payment collection, distribution and handling of returns. Many new jobs were created for hundreds of poor artisans in isolated Nepalese villages. The Rockefeller Foundation, which commissioned a strategic plan for PEOPLink, found that “Internet commerce is essential for third world artisan and SME development and PEOPLink can be a leader [in this area].”

However, while some reports suggest that PEOPLink is generating substantial revenue, with daily sales ranging from US$50–500, other reports indicate that PEOPLink has achieved very low sales. There seems to be little evidence to suggest that these operations are selling a significant amount of craft goods direct to consumers. According to a Department for International Development (DFID) report, PEOPLink has had a disappointing level of sales, with no producer contacted having sold any products through its site (Batchelor and Webb, 2002). PEOPLink is now focusing on its CatGen system, software to assist in the creation of on-line catalogues to enhance B2B (business-to-business) operations.

One area of e-commerce that shows potential is the promotion and marketing of pro-poor, community-based tourism. Pro-poor tourism aims to increase the net benefits for the poor from tourism, and ensure that tourism growth contributes to poverty reduction. It is not a specific product or sector of tourism, but a specific approach to tourism. Pro-poor tourism strategies unlock opportunities for the poor, whether for economic gain, other livelihood benefits or participation in decision-making (Ashley et al., 2001). Early experience shows that pro-poor tourism strategies are able to ‘tilt’ the industry at the margin, to expand opportunities for the poor and have potentially wide application across the industry. Poverty reduction through pro-poor tourism can therefore be significant at a local or district level. Moreover, the poverty impact may be greater in remote areas, though the tourism itself may be on a limited scale (Roe and Khanya).

Poor communities are often rich in natural assets—scenery, climate, culture and wildlife. Community-based tourism is closely associated with ecotourism and is regarded as a tool for natural and cultural resource conservation and community development. It is a community-based practice that provides contributions and incentives for natural and cultural conservation, as well as opportunities for community livelihood. Community-based tourism provides alternative economic opportunities in rural areas. It has the potential to create jobs and generate a wide spectrum of entrepreneurial opportunities for people from a variety of backgrounds, skills and experiences, including rural communities and especially women. [5]

Tourism and e-commerce are natural partners (UNCTAD, 2001). Tourism is highly information-intensive. During the intermediary period, the tourism product exists in the form of information only (reservation number, ticket, voucher). Value added by international tourism intermediaries, who are often no more than marketers and information handlers and who rarely own or manage physical tourism facilities, can be as high as 30 percent or more, which gives them control over terms and conditions throughout the whole value chain. Although it is the destination’s socioeconomic, cultural and geographical content that forms the fundamental tourism product, it often happens that with each intermediary party taking a commission, little income remains for the destination at which the product is consumed. Electronic commerce for tourism (e-tourism) can disintermediate and deconstruct the tourism value chain, driving income closer towards the actual providers of tourism experiences. But the lack of on-line payment facilities, which are fundamental to closing sales, and the lack of local financial and technological infrastructure that is typical of rural and remote locations in developing countries, regularly force e-businesses to establish external subsidiaries and accounts, thereby perpetuating dependence on established intermediary operations.

Supporting good governance

E-governance is an area of ICT use that shows rapidly increasing promise for alleviating the powerlessness, voicelessness, vulnerability and fear dimensions of poverty. Where national or local governments have taken positive steps to spread democracy and inclusion to the poor, ICTs have dramatically demonstrated how they can be used to facilitate the process. The effect can be to break down traditional patterns of exclusion, opaqueness, inefficiency and neglect in public interactions with government officials (Bhatnagar, 2002).

In the Bhoomi project of online delivery of land titles in Karnataka, India, the Department of Revenue in Karnataka has computerized 20 million records of land ownership of 6.7 million farmers in the state. Previously, farmers had to seek out the village accountant to get a copy of the Record of Rights, Tenancy and Crops (RTC), a document needed for many tasks such as obtaining bank loans. There were delays and harassment and bribes often had to be paid. Today, for a fee of Rs.15, a printed copy of the RTC can be obtained on-line at computerized land record kiosks (Bhoomi centres) in nearly 200 taluks (districts) or at Internet kiosks in rural area offices. The Bhoomi software incorporates the bio-logon metrics system, which authenticates all users of the software using their fingerprint. A log is maintained of all transactions in a session. This makes an officer accountable for his decisions and actions. Previously, requests for changes to the records could take months to process and were subject to manipulation by the officers. Now, farmers can get an RTC for any parcel of land and a Khata extract (statement of total land holdings of an individual) in 5-30 minutes from an RTC information kiosk at the taluk headquarters.

There are plans to use the Bhoomi kiosk for disseminating other information, such as lists of destitute and handicapped pensioners, families living below the poverty line, concession food grain cardholders and weather information. The response of the people at taluk level has been overwhelming. Queues can be seen at the kiosks, and 330,000 people have paid the fee without complaint. When asked what single factor contributed most to the success of this project, the manager unhesitatingly replied, “political will”.

In Kerala, the state government is sponsoring the e-shringla project to set up Internet-enabled information kiosks throughout the State. The concept grew out of the state government’s experiences with a bill-payment service called FRIENDS, (Fast, Reliable, Instant, Efficient, Network for Disbursement of Service), which operates as a one-stop service centre equipped with computers for paying bills as well as for obtaining applications and remitting registration fees. E-shringla is the next logical step from FRIENDS. It networks with a variety of government departments and providing Internet access, enabling online services and e-commerce facilities for citizens. The Karakulam Panchayat has developed a Knowledge Village Portal as an example of a community portal system that delivers a range of government and community information.

Since January 2000, Gyandoot, a government-owned computer network, has been making government more accessible to villagers in the poor, drought-prone Dhar district of Madhya Pradesh. Gyandoot reduces the time and money people spend trying to communicate with public officials and provide immediate, transparent access to local government data and documentation. For minimal fees, Intranet kiosks provide caste, income, and domicile certificates, helping villagers avoid the common practice of paying bribes to officials. The kiosks also allow small farmers to track crop prices in the region’s wholesale markets, enabling them to negotiate better terms for crop sales. Other services include on-line applications for land records and a public complaint line for reporting broken irrigation pumps, unfair prices, absentee teachers and other problems. Kiosks are placed in villages located on major roads or holding weekly markets, to facilitate access by people in neighbouring villages. The network of about 30 kiosks covers more than 600 villages and is run by local private operators along commercial lines (World Bank, 2002).

Building capacity and capability

The meaning of the term capacity building seems to vary according to the user, but there appears to be no doubt that ICTs can help achieve it. Capacity building refers to developing an organization’s (or individual’s) core skills and capabilities to help it (him/her) achieve its (his/her) development goals. This definition suits the context of ICTs well as it assumes knowledge of the existence of development goals without which ICTs are unlikely to be of much value. Hans d’Orville, Director of the IT for Development Programme, Bureau for Development Policy, United Nations Development Programme, puts it simply: “The full realisation of the potential of ICTs requires skills, training, individual and institutional capacity among the users and beneficiaries”.

But the key question for poverty alleviation seems to be whether ICTs can build the capacity of the poorest people to achieve whatever goals they may have. If you are illiterate, destitute, disabled, malnourished, low caste, homeless and jobless, will ICTs help? The most likely scenario is that these very poor people will receive assistance from organizations and institutions that use ICTs and whose programmes specifically target them as beneficiaries.

ICTs in the form of multimedia community centres/telecentres, especially at the rural level can act as a nodal point for community connectivity, local capacity-building, content development and communications, and serve as hubs for applications, such as distance education, telemedicine, support to small, medium-sized and micro-credit enterprises, promotion of electronic commerce, environmental management, and empowerment of women and youth. Where such services have a pro-ultra-poor strategy, then the benefits of ICTs can be directed to them.

The Village Information Shops in Pondicherry, India have adopted such a programme. They have used ICTs to build awareness in poor communities of the government programmes and entitlements that are available for their assistance. They have a database of more than 100 such entitlements. Moreover, they have acquired the list of ultra-poor people that the government maintains, and made it available through the centres. The staff proactively notifies the people on the list that they are entitled to claim certain benefits (the government officials had not been well known for promoting these schemes), and they provide assistance in submitting the claims, contacting the appropriate bureaucrat and moving the application forward. As a result, every household in one fishing village is now in receipt of the housing subsidies to which they are entitled, whereas previously none of them were.

Capacity building also relates to the accumulation of social capital, which refers to those features of social organization such as networks, norms and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit. The establishment of networks for mutual benefit can be nurtured and extended through the use of ICTs. ICTs can help create and sustain on-line and off-line networks that introduce and interconnect people who are working toward similar goals.

Many organizations in the women’s movement recognize this potential and have projects that provide support for ICT to be used as an advocacy tool. ICTs can also enable certain individuals, especially early adopters, to spark catalytic change in their communities. For example, one very resourceful lady in a small Mongolian town who single-handedly runs an NGO supporting women’s micro-enterprises used the local telecentre to contact a donor agency in the UK and received an award of US$10,000, a huge sum in that context, to help her in her work.

The 220,000 women members of India’s Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) who earn a living through their own labour or through small businesses have started using telecommunications as a tool for capacity building among the rural population. SEWA uses a combination of landline and satellite communication to conduct educational programs on community development by distance learning. The community development themes covered in the education programs delivered include organizing, leadership building, forestry, water conservation, health education, child development, the Panchayati Raj System and financial services.

Enriching culture

ICTs can simultaneously be a threat and an opportunity to a culture. On the one hand, ICTs threaten to engulf indigenous minorities in the relentless processes of globalization. On the other hand, ICTs can be used as tools to help indigenous minorities to engage positively with globalization on their own terms. The concern at this stage is that the former is more likely to happen than the latter. ICTs alone will not achieve cultural diversity. As with all successful applications of ICTs, adaptations in the behaviour of individuals, groups and institutions are necessary before significant cultural benefits can emerge from the deployment of ICTs.

Existing institutions such as libraries and museums can help in the process of democratizing ownership of cultural assets, provided they face up to the limitations of their traditional roles. The Internet has made the conventional role of libraries and museums obsolete. Yet such institutions have major roles to play in mobilizing communities towards a more open and dynamic approach to the assembly and preservation of indigenous culture. Libraries and museums can facilitate a more dispersed pattern of ownership and custodianship of cultural artefacts that can be increasingly represented digitally. Networks that connect digitized cultural artefacts to the communities from which they were derived can be used to foster a wider appreciation of their value and importance as well as a more inclusive approach to how they are used and interpreted.

Studies of indigenous communities regularly point to the importance they place on their cultural heritage. But they also highlight the almost complete lack of control or participation such communities have in how their culture is collected or represented. The Kelabit people in Sarawak, for example, do not feel that they exercise ownership rights over their own cultural heritage. They are concerned that outsiders are able to more easily gain access to both the records and the artefacts related to their cultural heritage than they are. They are also concerned that this can give rise to misinterpretation of the meaning of their cultural heritage. They feel powerless to present to the outside world a picture of themselves, their history and achievements, which they themselves would wish to have known. They see the situation getting worse rather than better, as technology empowers a few people to engage with information relating to their heritage, while depriving the majority of an equal opportunity.

On the other hand, ICTs can be used to help rural indigenous and minority communities achieve custodial ownership and rights of interpretation and commercialization over their own cultural heritage. The Kelabit people of Sarawak are in fact starting to use their telecentre to redress this imbalance by recording their oral histories and genealogical records.

UNESCO is currently formulating a charter and guidelines for the preservation of digital heritage. Digital heritage is that part of all digital materials that has lasting value and significance. New strategies need to be developed to ensure that they are saved for posterity. Digital heritage is either ‘born digital’ where there is no other format, or created by conversion from existing materials in any language and area of human knowledge or expression. It includes linear text, databases, still and moving images, audio and graphics, as well as related software, whether originated on-line or off-line, in all parts of the world. The preamble to the UNESCO charter states that the intellectual and cultural capital of all nations in digital form is at risk due to its ephemeral nature. Thus, the charter details the need for digital preservation principles and strategies to ensure that this heritage is available to all now and into the future.

Aside from digitization of indigenous cultural artefacts, ICTs provide a means for cultural communities to strengthen cultural ties. To cite an example, the Internet is a means to unite the more than five million Assyrians who are scattered all over the U.S., Europe and Australia. The Assyrians are the direct descendants of the ancient Assyrian and Babylonian empires. The Internet is finally uniting Assyrian communities, regardless of their geographic, educational, and economic backgrounds (Albert).

ICTs can either homogenize cultures or provide an opportunity to celebrate the diversity of culture. Whichever outcome prevails depends on how ICTs are used. Among the few experimental ICT projects involving ethnic indigenous people, short-term thinking and the pressure for tangible results (deliverables) cause donors to focus on poverty alleviation outcomes alone. However, when you talk to members of the communities themselves, it is easy to find considerable interest in using the technology for preserving and strengthening their cultural heritage.

Supporting agriculture

Research suggests that increasing agricultural productivity benefits the poor and landless through increased employment opportunities. Because the vast majority of poor people live in rural areas and derive their livelihoods directly or indirectly from agriculture, support for farming is a high priority for rural development. ICTs can deliver useful information to farmers in the form of crop care and animal husbandry, fertilizer and feedstock inputs, drought mitigation, pest control, irrigation, weather forecasting, seed sourcing and market prices. Other uses of ICTs can enable farmers to participate in advocacy and cooperative activities.

To illustrate how useful ICTs can be for farmers, consider the case of farmers in India who in the past were harvesting their tomatoes at the same time, giving rise to a market glut that pushed prices to rock bottom. At other times, when tomatoes weren’t available and the prices shot up, the farmers had none to sell. Now, they use a network of telecentres to coordinate their planting so that there is a steady supply to the markets and more regulated and regular prices.

The Maharashtra State government has plans of linking 40,000 villages with Agronet, a specially developed software package for farmers that aims to provide the latest information on agriculture.

Samaikya Agritech P. Ltd. in Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh operates 18 “Agritech Centres”, which provide agricultural support services to farmers on a commercial basis. They are permanently operated by qualified agricultural graduates called Agriculture Technical Officers (ATO) and are equipped with computers linked to the head office in Hyderabad through a modem-to-modem telephone connection. Through these centres Samaikya provides technical assistance to member farmers; inputs such as seeds, fertilizers and pesticide, machinery hire, tools and spares for sale; soil and water analyses; weather monitoring; field mapping; weekly field inspections and field visits by specialists.

Farmers register with centres and pay per growing season (two or three seasons per year) a fee of Rs.150 (about US$3) per acre/crop. A farmer registers by the field and receives support services that are specific to the fields registered. On registration, the farmer provides detailed information concerning his farming activities; the information is kept in the centre’s database, providing the basis for the technical support provided. The centre in the village of Choutkur has 53 registered farmers, covering 110 acres of registered land. This is out of a total of around 1,000 farmers within the centre’s catchment area. Major crops include sugar cane, padi and pulses.

Advice from the centres is based on data generated from pre-validated crop cultivation practices adopted in the State and provided by government agricultural services and local institutions. Farming information is up-linked from headquarters to the computers at the centres. If farmers have specific needs for information that cannot be satisfied immediately by the ATO at the centre, then the technician completes an on-line enquiry form on the computer and transmits this via modem to the headquarters. At the headquarters, specialists with more experience and qualifications organize and coordinate replies, which are typically transmitted back to the centre within 24 hours. The database and information systems are operated in the English language. Information is interpreted for the farmer by the ATO. Because some farmers are illiterate, the technicians have to spend time with explanations and descriptions. There is no standard for a computerized Telegu script.

Prior to setting up a centre, Samaikya performs a survey of local farming and cultivation practices and ascertains the political and cultural context of the potential centre. It conducts a pre-launch programme to familiarize farmers with the services. One centre closed down within three months of opening as no farmers registered for the service. This was due to the pressure placed on them by local marketeers, financiers and suppliers of inputs who perceived a threat to their livelihoods from the competing Samaikya services. Farmers were told that anyone who registered with the centre would not receive credit or essential supplies.

Creating employment opportunities

Two areas of employment opportunity arise from the deployment of ICTs. First, unemployed people can use ICTs to discover job opportunities. Second, they can become employed in the new jobs that are created through the deployment of ICTs.