Iranian History/The Islamic Republic of Iran

The Iranian Revolution (also known as the Islamic Revolution,[1][2][3][4][5][6] Persian: انقلاب اسلامی, Enghelābe Eslāmi) was the revolution that transformed Iran from a monarchy[7] under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to an Islamic republic under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of the revolution and founder of the Islamic Republic.[8] It has been called "the third great revolution in history," following the French and Russian revolutions,[9] and an event that "made Islamic fundamentalism a political force ... from Morocco to Malaysia."[10]

Although some might argue that the revolution is still ongoing (not complete), its time span can be said to have begun in January 1978 with the first major demonstrations to overthrow the Shah (empowered by external Anglo-American interests, both political as economical),[11] and concluded with the approval of the new theocratic Constitution — whereby Khomeini became Supreme Leader[12] of the country — in December 1979. In between, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi fled Iran in January 1979 after strikes and demonstrations paralyzed the country, and on February 1, 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Tehran to a greeting by several million Iranians.[13] The final collapse of the Pahlavi dynasty occurred shortly after on February 11 when Iran's military declared itself "neutral" after guerrillas and rebel troops overwhelmed troops loyal to the Shah in armed street fighting. Iran officially became an Islamic Republic on April 1, 1979, when Iranians overwhelmingly approved a national referendum to make it so.[14]

The revolution was unique for the surprise it created throughout the world:[15] it lacked many of the customary causes of revolution — defeat at war, a financial crisis, peasant rebellion, or disgruntled military;[16] produced profound change at great speed;[17] overthrew a regime thought to be heavily protected by a lavishly financed army and security services;[18][19] and replaced an ancient monarchy with a theocracy based on Guardianship of the Islamic Jurists[20] (or velayat-e faqih). Its outcome, an Islamic Republic "under the guidance of an 80-year-old exiled religious scholar from Qom[21]," was, as one scholar put it, "clearly an occurrence that had to be explained.…"[22]

Not so unique but more intense is the dispute over the revolution's results. For some it was an era of heroism and sacrifice that brought forth nothing less than the nucleus of a world Islamic state, "a perfect model of splendid, humane, and divine life… for all the peoples of the world."[23] At the other extreme, disillusioned Iranians explain the revolution as a time when "for a few years we all lost our minds,"[24] and as a system that, "promised us heaven, but ... created a hell on earth." [25]

Reasons for the revolution

[edit | edit source]Explanations advanced for why the revolution happened and took the form it did include actions of the Shah and the mistakes and successes of the different political forces:

Errors of the Shah

[edit | edit source].[26] This included his original installation by Allied Powers and assistance from the CIA in 1953 to restore him to the throne, the use of large numbers of US military advisers and technicians and the capitulation or granting of diplomatic immunity from prosecution to them, all of which led nationalistic Iranians, both religious and secular[27] to consider him a puppet of the West;[28][29]

- Extravagance, corruption and elitism (both real and perceived) of the Shah's policies and of his royal court;[30][31]

- His failure to cultivate supporters in the Shi'a religious leadership to counter Khomeini's campaign against him;[32][33]

- Focusing of government surveillance and repression on the People's Mujahedin of Iran, the communist Tudeh Party of Iran, and other leftist groups, while the more popular religious opposition organized, grew and gradually undermined the authority of his regime;[34][35][36]

- Authoritarian tendencies that violated the Iran Constitution of 1906,[37][38] including repression of dissent by security services like the SAVAK,[39] followed by appeasement and appearance of weakness as the revolution gained momentum;[40][41]

- Failure of his overly ambitious 1974 economic program to meet expectations raised by the oil revenue windfall. Bottlenecks, shortages and inflation were followed by austerity measures, attacks on alleged price gougers and black-markets, that angered both the bazaar and the masses;[42]

- His antagonizing of formerly apolitical Iranians, especially merchants of the bazaars, with the creation of a single party political monopoly (the Rastakhiz Party), with compulsory membership and dues, and general aggressive interference in the political, economic, and religious concerns of people's lives;[43]

- His overconfident neglect of governance and preoccupation with playing the world statesman during the oil boom,[44] followed by a loss of self-confidence and resolution[40] and a weakening of his health from cancer[45] as the revolution gained momentum;

- Underestimation of the strength of the opposition — particularly religious opposition — and the failure to offer either enough carrots or sticks. Efforts to please the opposition were "too little too late,"[46] but no concerted counter-attack was made against the revolutionaries either.[40]

- Failure to prepare and train security forces for dealing with protest and demonstration, failure to use crowd control without excessive violence[47] (troops used live ammunition, not Plexiglas shields or water cannons),[48] and use of the military officer corps more as a powerbase to be pampered than as a force to control threats to security;[49]

- The personalised nature of the Shah's government, where prevention of any possible competitor to the monarch trumped efficient and effective government and led to the crown's cultivation of divisions within the army and the political elite,[50] and ultimately to a lack of support for the regime by its natural allies when needed most (thousands of upper and middle class Iranians and their money left Iran during the beginning of the revolution).[51]

Failures and successes of other political forces

[edit | edit source]- Overconfidence of the secularists and modernist Muslims, of liberals and leftists in their power and ability to control the revolution;[52]

- Shrewdness of the Ayatollah Khomeini in winning the support of these liberals and leftists when he needed them to overthrow the Shah by underplaying his hand and avoiding issues (such as rule by clerics or "guardianship of the jurists") he planned to implement but knew would be a deal breaker for his more secular and modernist Muslim allies;[53]

- Cleverness and energy of Khomeini's organizers in Iran who outwitted the Shah's security forces and won broad support with their tactical ingenuity — amongst other things, convincing Iranians that the Shah's security was more brutal than it was;[49]

- The Ayatollah Khomeini's self-confidence, charisma, and most importantly his ability to cast himself as following in the footsteps of the beloved Shi'a Imam Husayn ibn Ali, while portraying the Shah as a modern day version of Hussein's foe, the hated tyrant Yazid I;[54] and so to be seen by millions as a savior figure,[55] and inspiring hundreds to feats of martyrdom fighting the regime.

- Policies of the American government, which helped create an image of the Shah as American "puppet" with their high profile and the 1953 subversion of the government on his behalf, but helped trigger the revolution by pressuring the Shah to liberalize, and then finally may have heightened the radicalism of the revolution by failing to read its nature accurately (particularly the goals of Khomeini), or to clearly respond to it.[56][57][58]

Ideology of Iranian revolution

[edit | edit source]| A Wikibookian questions the neutrality of this page. You can help make it neutral, request assistance, or view the relevant discussion. |

The ideology of the revolution can be summarized as populist, nationalist and most of all Shi'a Islamic.

Contributors to the ideology included Jalal Al-e-Ahmad, who formulated Gharbzadegi -- the idea that Western culture was a plague or an intoxication that alienated Muslims from their roots and identity and must be fought and expelled.[59] Ali Shariati influenced many young Iranians with his interpretation of Islam as the one true way of awakening the oppressed and liberating the Third World from colonialism and neo-colonialism.[60]

And most of all Ayatollah Khomeini, the man who dominated the revolution itself. He preached that revolt, and especially martyrdom, against injustice and tyranny was part of Shia Islam,[61] that Muslims should reject the influence of both Soviet and American superpowers in Iran with the slogan "not Eastern, nor Western - Islamic Republican" (Persian: نه شرقی نه غربی جمهوری اسلامی)

Even more importantly he developed the ideology of velayat-e faqih, that Muslims, in fact everyone, required "guardianship," in the form of rule or supervision by the leading Islamic jurist or jurists -- such as Khomeini himself.[62] Rule by Islamic jurists would protect Islam from innovation and deviation by following traditional sharia law exclusively, and in so doing would prevent poverty, injustice, and the "plundering" of Muslim land by foreign unbelievers.[63]

Establishing and obeying this Islamic government was so important it was "actually an expression of obedience to God," ultimately "more necessary even than prayer and fasting" for Islam because without it true Islam will not survive. [64] It was a universal principle, not one confined to Iran. All the world needed and deserved just government, i.e. true Islamic government. [65]

This revolutionary vision of theocratic government was in stark contrast to that of other revolutionaries - traditionalist Shia clerics, Iran's democratic secularists and Islamic leftists. Consequently, prior to the overthrow of the Shah, the revolution's ideology was known for its "imprecision"[66] or "vague character,"[67] with the specific character of velayat-e faqih/theocratic waiting to be made public when the time was right.[68] Khomeini believed the opposition to velayat-e faqih/theocratic government by the other revolutionaries was the result of propaganda campaign by foreign imperialists eager to prevent Islam from putting a stop to their plundering. This propaganda was so insidious it had penetrated even Islamic seminaries and made it necessary to "observe the principles of taqiyya" (i.e. dissimulation of the truth in defense of Islam), when talking about (or not talking about) Islamic government. [69][70]

In the end, the revolutionary ideology prevailed. Khoemini and his core supporters worked determinedly to establish a government led by Islamic clerics, and opposition from the different factions was defeated, sometimes violently. (see below: Khomeini takes power, Consolidation of power by Khomeini and Opposition to the revolution)

Background of the revolution

[edit | edit source]Pahlavi dynasty and its secular, anti-clerical policies

[edit | edit source]Following the Iranian Constitutional Revolution of 1906, Iran's first constitution came into effect, approved by the Majlis. The constitution established a special place for Twelver Shi'a Islam. It declared Islam the official religion of Iran, specified that the Shi'a clergy were to determine whether laws passed in the majlis were "comfortable to the principles of Islam", and that of committee of the clergy were to approve all laws, and required the Shah to promote the Twelver Shi'a Islam, and adhere to its principles. [71] (See: Supplementary Fundamental Laws)

However, after the rise of the Pahlavi dynasty, Reza Pahlavi, like his contemporary Atatürk, tried to secularize and westernize Iran. He marginalized the Shi'a clergy, and put an end to Islamic laws and tried unveiling women. Reza Pahlavi tried to secularize Iran by ignoring the religious constitution. By the mid-1930s, Reza Shah's style of rule had caused intense dissatisfaction to the Shi'a clergy throughout Iran, thus creating a gap between religious institutions and the government.[72] He banned traditional Iranian dress for both men and women, in favour of western dress.[73] Women who resisted this compulsory unveiling had their chadors forcibly removed and torn. He dealt harshly with opposition: troops were sent to massacre protesters at mosques and nomads who refused to settle. Both liberal and religious newspapers were closed and many imprisoned.[73]

1940s: The Shah comes to power

[edit | edit source]Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi came to power in 1941 after the deposing of his father, Reza Shah, by an invasion of allied British and Soviet troops in 1941. Reza Shah, a military man, had been known for his determination to modernize Iran and his hostility to the clerical class (ulema). Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi held power until the 1979 revolution with a brief interruption in 1953; when he had faced an attempted revolution. In that year he briefly fled the country after a power-struggle had emerged between himself and his Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh, who had nationalized the country's oil fields and sought control of the armed forces. Mossadegh had been voted into power through a democratic election. Through a military coup d'etat aided by a CIA and MI6 covert operation, codenamed Operation Ajax, Mossadegh was overthrown and arrested and the Shah returned to the throne. Iranian sentiment has remembered this undermining of Iranian democratic process as a chief complaint against the United States and Britain.

Like his father, Shah Pahlavi vainly sought to modernize and "westernize" a country severely underdeveloped by his own politics. As R. Kapuchinsky has authoritatively stated, these attempts were daunted by the lack of education of Iran's labor force and big gaps in technical and industrial facilities. He retained close relationships with the United States and several other western countries, and was frequently recognized by the American presidential administrations for his policies and steadfast opposition to Communism. Opposition to his government came from leftist, nationalist and religious groups who criticized it for violating the Iranian constitution, political corruption, and the savage political oppression of the SAVAK (secret police). Of ultimate importance to the opposition were the religious figures of the Ulema, or clergy, who had shown themselves to be a vocal political voice in Iran with the 19th century Tobacco Protests against a concession to a foreign interest. The clergy had a significant influence on the majority of Iranians who tended to be the religious, traditional and alienated from any process of Westernization.

1960s: Rise of Ayatollah Khomeini

[edit | edit source]

Khomeini, the future leader of the Iranian revolution was declared as a marja, by the Society of Seminary Teachers of Qom in 1963, following the death of Grand Ayatollah Seyyed Husayn Borujerdi. He also came to political prominence that year leading opposition to the Shah and his program of reforms known as the White Revolution. Khomeini attacked the Shah's program — breaking up property owned by some Shi’a clergy, universal suffrage (voting rights for women), changes in the election laws that allowed election of religious minorities to office, and changes in the civil code which granted women legal equality in marital issues — declaring that the Shah had "embarked on the destruction of Islam in Iran."[74]

Following Khomeini's public denunciation of the Shah as a "wretched miserable man" and arrest on June 5, 1963, three days of major riots erupted throughout Iran with police using deadly force to quell it. The Pahlavi government said 86 killed in the rioting; Khomeini supporters stated at least 15,000 killed;[75] while some say that post-revolutionary reports from police files indicate more than 380 were killed.[76] Khomeini was kept under house arrest for 8 months and released. He continued to agitate against the Shah on issues including the Shah's close cooperation with Israel and especially the Shah's "capitulations" of extending diplomatic immunity to American military personnel. In November 1964 Khomeini was re-arrested and sent into exile where he remained for 14 years until the revolution.

A period of "disaffected calm" followed.[77] Dissent was suppressed by SAVAK security service but the budding Islamic revival began to undermine the idea of Westernization as progress that was the basis of the Shah's secular regime. Jala Al-e Ahmad's idea of Gharbzadegi (the plague of Western culture), Ali Shariati's leftist interpretation of Islam, and Morteza Morahhari's popularized retellings of the Shia faith, all spread and gained listeners, readers and supporters.[59] Most importantly, Khomeini developed and propagated his theory that Islam requires an Islamic government by wilayat al-faqih, i.e. rule by the leading Islamic jurist. In a series of lectures in early 1970, later published as a book (Hokumat-e Islami, Velayat-e faqih, or Islamic government, Guardianship of the jurist in English), Khomeini argued that Islam requires obedience to sharia law alone, and this in turn requires that the leading Islamic jurist or jurists must not only guide Muslims but run the government.

While Khomeini did not talk about this concept in interviews and talks with outsiders, the book was widely distributed in religious circles, especially among Khomeini's students (talabeh), ex-students (clerics), and small business leaders. This group also began to develop what would become a powerful and efficient network of opposition[78] inside Iran, employing mosque sermons, smuggled cassette speeches by Khomeini, and other means. Added to this religious opposition were more modernist students and guerrilla groups[79] who admired Khomeini's leadership though they were to clash with and be suppressed by his movement after the revolution.

1970s: Pre-revolutionary conditions and events inside Iran

[edit | edit source]Several events in the 1970s set the stage for the 1979 revolution:

In October 1971, the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire was held at the site of Persepolis. Only foreign dignitaries were invited to the three-day party whose extravagances included over one ton of caviar, and preparation by some two hundred chefs flown in from Paris. Cost was officially $40 million but estimated to be more in the range of $100–120 million.[80] Meanwhile, the provinces of Baluchistan and Sistan, and even Fars where the celebrations were held, were suffering from drought. "As the foreigners reveled on drink forbidden by Islam, Iranians were not only excluded from the festivities, some were starving."[81]

By late 1974 the oil boom had begun to produce not "the Great Civilization" promised by the Shah, but an "alarming" increase in inflation and waste and an "accelerating gap" between the rich and poor, the city and the country.[82] Nationalistic Iranians were angered by the tens of thousand of skilled foreign workers who came to Iran, many of them to help operate the already unpopular and expensive American high-tech military equipment that the Shah had spent hundreds of millions of dollars on.

The next year the Rastakhiz party was created. It became not only the only party Iranians could belong to, but one the "whole adult population" was required to belong and pay dues to.[83] Attempts by this party to take a populist stand with "anti-profiteering" campaigns fining and jailing merchants, proved not only economically harmful but also politically counterproductive. Inflation was replaced by a black market and declining business activity. Merchants were angered and alienated.[84]

In 1976, the Shah's government angered pious Iranian Muslims by changing the first year of the Iranian solar calendar from the Islamic hijri to the ascension to the throne by Cyrus the Great. "Iran jumped overnight from the Muslim year 1355 to the royalist year 2535."[85] The same year the Shah declared economic austerity measures to dampen inflation and waste. The resulting unemployment disproportionately affected the thousands of recent poor and unskilled migrants to the cities. Culturally and religiously conservative and already disposed to view the Shah's secularism and Westernization as "alien and wicked",[86] many of these same people went on to form the core of revolution's demonstrators and "martyrs".[87]

In 1977 a new American President, Jimmy Carter, was inaugurated. In hopes of making post-Vietnam American power and foreign policy more benevolent, he created a special Office of Human Rights which sent the Shah a "polite reminder" of the importance of political rights and freedom. The Shah responded by granting amnesty to 357 political prisoners in February, and allowing Red Cross to visit prisons, beginning what is said to be 'a trend of liberalization by the Shah'. Through the late spring, summer and autumn liberal opposition formed organizations and issued open letters denouncing the regime.[88] Later that year a dissent group (the Writers' Association) gathered without the customary police break-up and arrests, starting a new era of political action by the Shah's opponents.[89]

That year also saw the death of the very popular and influential modernist Islamist leader Ali Shariati, allegedly at the hands of SAVAK, removing a potential revolutionary rival to Khomeini. Finally, in October Khomeini's son Mostafa died. Though the cause appeared to be a heart attack, anti-Shah groups blamed SAVAK poisoning and proclaimed him a 'martyr.' A subsequent memorial service for Mostafa in Tehran put Khomeini back in the spotlight and began the process of building Khomeini into the leading opponent of the Shah.[90][91]

Oppositions groups and organizations

[edit | edit source]Opposition groups under the Shah tended to fall into three major categories: constitutionalist, Marxist, and Islamist.

Constitutionalists, including National Front of Iran, wanted to revive constitutional monarchy including free elections. Without elections or outlets for peaceful political activity though, they had lost their relevance and had little following.

Marxists groups were illegal and heavily suppressed by SAVAK internal security apparatus. They included the Tudeh Party of Iran; the Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas (OIPFG) and the breakaway Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas (IPFG), two armed organizations; and some minor groups.[92] Their aim was to defeat the Pahlavi regime by assassination and guerilla war. Although they played an important part in the revolution, they never developed a large base of support.

Islamists were divided into several groups. The Freedom Movement of Iran was formed by religious members of the National Front of Iran. It also was a constitutional group and wanted to use lawful political methods against the Shah. This movement comprised Bazargan and Taleqani. The People's Mujahedin of Iran was a quasi-Marxist armed organization that opposed the influence of the clergy and later fought the Islamic government. Individual writers and speakers like Ali Shariati and Morteza Morahhari did important work outside of these parties and groups.

Amongst the close followers of Ayatollah Khomeini, there were some minor armed Islamist groups which joined together after the revolution in the Mojahedin of the Islamic Revolution Organization. The Coalition of Islamic Societies was founded by religious bazaaris[93] (traditional merchants). The Combatant Clergy Association comprised Motahhari, Beheshti, Bahonar, Rafsanjani and Mofatteh who later became the major governors of Islamic Republic. They used a cultural approach to fight the Shah.

Because of internal repression, opposition groups abroad, like the Confederation of Iranian students, the foreign branch of Freedom Movement of Iran and the Islamic association of students, were important to the revolution.

1978: Outbreak of the Revolution

[edit | edit source]The early visible opposition by liberals was based in the urban middle class, a section of the population that was fairly secular and wanted the Shah to adhere to the Iranian Constitution of 1906, not a republic ruled by Islamic clerics.[94] Prominent in it was Mehdi Bazargan and his liberal, moderate Islamic group Freedom Movement of Iran, and the more secular National Front.

The clergy were divided, some allying with the liberal secularists, and others with the Marxists and Communists. Khomeini, who was in exile in Iraq, worked to unite clerical and secular, liberal and radical opposition under his leadership[95] by avoiding specifics — at least in public — that might divide the factions.[96]

The various anti-Shah groups operated from outside Iran, mostly in London, Paris, Iraq, and Turkey. Speeches by the leaders of these groups were placed on audio cassettes to be smuggled into Iran.

The first major demonstration

[edit | edit source]The first of the major demonstrations against the Shah led by Islamic groups came in January 1978. Angry students and religious leaders in the city of Qom demonstrated against a libelous story attacking Khomeini run in the official press. The army was sent in, dispersing the demonstrations and killing several students (two according to the government, 70 according to the opposition).[97]

According to the Shi'ite customs, memorial services are held forty days after a person's death. In mosques across the nation, calls were made to honour the dead students. Thus on February 18 groups in a number of cities marched to honour the fallen and protest against the rule of the Shah. This time, violence erupted in Tabriz, and over a hundred demonstrators were killed. The cycle repeated itself, and on March 29, a new round of protests began across the nation. Luxury hotels, cinemas, banks, government offices, and other symbols of the Shah regime were destroyed; again security forces intervened, killing many. On May 10 the same occurred.

Ayatollah Shariatmadari joins the opposition

[edit | edit source]In May, government commandos burst into the home of Ayatollah Kazem Shariatmadari, a leading cleric and political moderate, and shot dead one of his followers right in front of him. Shariatmadari abandoned his quietist stance and joined the opposition to the Shah.[98]

The Shah attempted to appease protestors by dampening inflation, making appeals to the moderate clergy, and by firing his head of SAVAK and promising free elections the next June.[99] But the anti-inflationary cutbacks in spending led to layoffs — particularly among young, unskilled workers living in city slums. By summer 1978, these workers, often from traditional rural backgrounds, joined the street protests in massive numbers. Other workers went on strike and by November the economy was crippled by shutdowns.[100]

The Shah approaches the United States

[edit | edit source]

Facing a revolution, the Shah appealed to the United States for support. Because of its history and strategic location, Iran was important to the United States. It was a pro-American country sharing a long border with America's cold war rival, the Soviet Union, and the largest, most powerful country in the oil-rich Persian Gulf. But the Pahlavi regime had also recently garnered unfavorable publicity in the West for its human rights record.[101]

The Carter administration followed "no clear policy" on Iran.[102] The U.S. ambassador to Iran, William H. Sullivan, recalls that the U.S. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski “repeatedly assured Pahlavi that the U.S. backed him fully." President Carter arguably failed at following up on those assurances. On November 4, 1978, Brzezinski called the Shah to tell him that the United States would "back him to the hilt." At the same time, certain high-level officials in the State Department believed the revolution was unstoppable.[103] After visiting the Shah in summer of 1978, Secretary of the Treasury Blumenthal complained of the Shah's emotional collapse, reporting, "You've got a zombie out there."[104] Brzezinski and Energy Secretary James Schlesinger (Secretary of Defense under Ford) were adamant in their assurances that the Shah would receive military support. Brzezinski still advocated a U.S. military intervention to stabilize Iran even when the Shah's position was believed to be untenable. President Carter could not decide how to stabilize the situation; he was certainly against another coup. Initially, there appeared to be support for a peaceful transfer of power, however this option evaporated when Khomeini and his followers swept through the country, taking power on February 12, 1979. Many Iranians believe the lack of intervention and sometime sympathy for the revolution by high-level American officials indicate the U.S. "was responsible for Khomeini's victory."[105] A more extreme position asserts that the Shah's overthrow was the result of a "sinister plot to topple a nationalist, progressive, and independent-minded monarch."[106]

Abadan arson attack

[edit | edit source]As violence continued, over 400 people died in the Cinema Rex Fire arson attack in August in Abadan. Although movie theaters had been a common target of Islamist demonstrators[107][108] such was the distrust of the regime and effectiveness of its enemies' communication skills that the public believed SAVAK had set the fire in an attempt to frame the opposition.[109] The next day 10,000 relatives and sympathizers gathered for a mass funeral and march shouting, ‘burn the Shah’, and ‘the Shah is the guilty one.’[110]

Black Friday

[edit | edit source]By September, the nation was rapidly destabilizing, with major protests becoming a regular occurrence. The Shah introduced martial law, and banned all demonstrations. A massive protest broke out in Tehran, in what became known as Black Friday.

The clerical leadership spread rumours that "thousands have been massacred by Zionist troops."[111] The troops were actually ethnic Kurds who had been fired on, and the number killed not 15,000 but more like 700,[112] but in the meantime the appearance of government brutality alienated much of the rest of the Iranian people and the Shah's allies abroad. A general strike in October resulted in the paralysis of the economy, with vital industries being shut down, "sealing the Shah's fate".[113]

Ayatollah Khomeini in Paris

[edit | edit source]

Shah decided to seek the deportation of Ayatollah Khomeini from Iraq and on September 24, 1978, Iraqi regime sieged the house of Khomeini in Najaf. He was informed that his continued residence in Iraq was contingent on his abandoning political activity, a condition he rejected. On October 3, he left Iraq for Kuwait, but was refused entry at the border. Finally October 6 Ayatollah Khomeini embarked for Paris. On October 10 he took up residence in the suburb of Neauphle-le-Château in a house that had been rented for him by Iranian exiles in France. From now on the journalists from across the world made their way to France, and the image and the words of the Ayatollah Khomeini soon became a daily feature in the world's media.[114]

Muharram protests

[edit | edit source]On December 2, during the Islamic month of Muharram, over two million people filled the streets of Tehran's Azadi Square (then Shahyad Square), to demand the removal of the Shah and return of Khomeini.[115]

Victory of revolution and fall of monarchy

[edit | edit source]The Shah leaves

[edit | edit source]

On January 16, 1979 the Shah and the empress left Iran at the demand of prime minister Dr. Shapour Bakhtiar (a long time opposition leader himself) and to scenes of spontaneous joy and the destruction "within hours of almost every sign of the Pahlavi dynasty."[116] Bakhtiar dissolved SAVAK, freed political prisoners, ordered the army to allow mass demonstrations, promised free elections and invited Khomeinists and other revolutionaries into a government of "national unity".[117] After stalling for a few days he allowed Ayatollah Khomeini to return to Iran, asking him to create a Vatican-like state in Qom and called upon the opposition to help preserve the constitution.

Khomeini's return and fall of the monarchy

[edit | edit source]

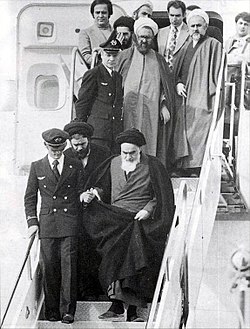

On February 1 1979 Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Tehran to rapturous greeting by several million Iranians. Khomeini had flown back to Iran in a chartered Air France Jumbo Jet.[118] Not only the undisputed leader of the revolution,[119] he had now become what some called a "semi-divine" figure, greeted as he descended from his airplane with cries of ‘Khomeini, O Imam, we salute you, peace be upon you.’[120] Crowds were now known to chant "Islam, Islam, Khomeini, We Will Follow You," and even "Khomeini for King."[121]

On the day of his arrival Khomeini made clear his fierce rejection of Bakhtiar's regime in a speech promising ‘I shall kick their teeth in.’ He appointed his own competing interim prime minister Mehdi Bazargan on February 4, `with the support of the nation’ and demanding ‘since I have appointed him, he must be obeyed.’ It was ‘God's government,’ he warned, disobedience against which was a ‘revolt against God.’[122] As Khomeini's movement gained momentum, soldiers began to defect to his side. On February 9 about 10 P.M. a fight broke out between loyal Immortal Guards and pro-Khomeini rebel Homafaran of Iran Air Force. Khomeini declaring jihad on loyal soldiers who did not surrender.[123] Revolutionaries and rebel soldiers gained the upper hand and began to take over police stations and military installations, distributing arms to the public. The final collapse of the provisional non-Islamist government came at 2 p.m. February 11 when the Supreme Military Council declared itself "neutral in the current political disputes… in order to prevent further disorder and bloodshed."[124][125] TV and Radio stations, palaces of Pahlavi dynasty and government buildings were then occupied by revolutionaries.

This period, from February 1 to 11, known as the "Decade of Fajr," is celebrated every year in Iran.[126][127] February 11 is "Islamic Revolution's Victory Day", a national holiday with state sponsored demonstrations in every city.[128][129]

Revolutionary organizations

[edit | edit source]Revolutionary Council

[edit | edit source]The "Revolutionary Council" was formed by Khomeini to manage the revolution on 12 January of 1979, shortly before he returned to Iran. Its existence was kept a secret during the early, less secure time of the revolution. Rafsanjani says Ayatollah Khomeini chose Beheshti, Motahhari, Rafsanjani, Bahonar and Musavi Ardabili as members. These invited others to serve: Bazargan, Taleqani, Khamenei, Banisadr, Mahdavi Kani, Yadollah Sahabi, Katirayee, Ahmad Sadr Haj Seyed Javadi, Qarani and Ali Asqr Masoodi.[130] This council suggested Mahdi Bazargan as the prime minister of the temporary government of Khomeini, and he accepted it.[27]

After the revolution took power, the council became a legislative body issuing decrees until the formation of first parliament[citation needed] on 12 August 1980.[131] The laws passed by this council were recognized as legitimate in the Islamic republic of Iran.[citation needed]

The Provisional Revolutionary Government

[edit | edit source]

The Provisional Revolutionary Government or "Interim Government of Iran" (1979–1980) was the first government established in Iran following the overthrow of the monarchy. It was formed by order of Ayatollah Khomeini on February 4, 1979, while Shapour Bakhtiar (the Shah's last Prime Minister) was still claiming power.[27]

Ayatollah Khomeini appointed Bazargan as the prime minister of "The Provisional Revolutionary Government" on February 4 1979. According to his commandment:[132]

"Mr. Engineer Bazargan, Based on the proposal of the Revolutionary Council, in accordance with the sharia based rights and legal rights which are both originated from the decisive and closely unanimous votes of Iranian nation for leadership of the movement, which in turn has been expressed in the vast gatherings and wide and numerous demonstrations throughout Iran and by virtue of my trust on your firm belief in the holy tenets of Islam ... I appoint you the authority to establish the interim government ... for the formation of a temporary government to arrange the affairs of the country and especially a national referendum vote about turning the country into an Islamic republic, ... All public offices, the army, and citizens shall furnish their utmost cooperation with your interim government so as to attain the high and holy goals of this Islamic revolution and to restore order and function to the affairs of the nation. I pray to God for the success of you and your interim government at this sensitive juncture of our nation's history.’’ Ruhollah Al-Musavi al-Khomeini

Elaborating further on his decree, Khomeini made it clear Iranians were commanded to obey Bazargan and that this was a religious duty.

As a man who, though the guardianship [Velayat] that I have from the holy lawgiver [the Prophet], I hereby pronounce Bazargan as the Ruler, and since I have appointed him, he must be obeyed. The nation must obey him. This is not an ordinary government. It is a government based on the sharia. Opposing this government means opposing the sharia of Islam ... Revolt against God's government is a revolt against God. Revolt against God is blasphemy.[133]

Mehdi Bazargan introduced his 7-member cabinet on February 14, 1979,[citation needed] three days after victory day when the army announced its neutrality in conflicts between Khomeini's and Bakhtiar's supporters. Bakhtiar resigned on the same day, February 11.

The PRG is often described as "subordinate" to the Revolutionary Council, and having had difficulties reigning in the numerous komiteh which were competing with its authority[134]

Prime Minister Bazargan resigned and his government fell after American Embassy officials were taken hostage on November 4, 1979. Power then passed into the hands of the Revolutionary Council. Bazargan had been a supporter of the original revolutionary draft constitution rather than theocracy by Islamic jurist, and his resignation was received by Khomeini without complaint, saying "Mr. Bazargan ... was a little tired and preferred to stay on the sidelines for a while." Khomeini later described his appointment of Bazargan as a "mistake."[135]

The Committees of Islamic Revolution

[edit | edit source]| |

A Wikibookian has nominated this page for cleanup. You can help make it better. Please review any relevant discussion. |

| A Wikibookian has nominated this page for cleanup. You can help make it better. Please review any relevant discussion. |

The first "komitehs" (from the French comité), or committees, "sprang up everywhere" as autonomous organizations in late 1978. Organized in mosques, schools and workplaces, they mobilized people, organized strikes and demonstrations, and distributed scarce commodities. After February 12th, many of the 300,000 rifles and sub-machine guns seized from military arsenals[136] ended up with the komitehs who confiscated property and arrested those they believed to be counter-revolutionaries. In Tehran alone there were 1500 committees. Inevitably there was conflict between the komitehs and the other sources of authority, particularly the Provisional Government.[137]

To deal with this, on February 12th, the committees of the Islamic revolution were charged with gathering weapons, organizing the armed revolutionaries, and generally fighting anarchy in the wake of the collapse of the police and weakness of the army. Khomeini put Ayatollah Mahdavi Kani in charge of the komiteh.[138] They also served as "the eyes and ears" of the new regime, and are credited by critics with "many arbitrary arrests, executions and confiscations of property".[139] In the summer of 1979, the komitehs were purged to eradicate the influence of the leftist guerilla movements that had infiltrated them.[140] In 1991 they were merged with the conventional police in a new organisation known as the Niruha-ye Entezami (Forces of Order).[141]

Islamic Republic Party

[edit | edit source]The Islamic republic party was started by Khomeini lieutenant Seyyed Mohammad Hosseini Beheshti and the Coalition of Islamic Societies within a few days of the Khomeini's arrival in Iran. It was made up of the Mojahedin of the Islamic Revolution (OMIR), merchants of the bazaar and "a large segment of the politically active clergy." It "operated on every level of society, from government offices to almost all city quarters..."[142] and worked to establish theocratic government by velayat-e faqih in Iran outmaneuvering opponents and wielding power on the street through the Hezbollah.

The party achieved a large majority in the first parliament but clashed with first president, Banisadr, who was not a member of the party. Banisadr supporters were suppressed and Banisadr impeached and removed from office June 21, 1981. A campaign of terror against the IRP followed, mounted by the guerrilla group MEK. On the 28 of June, 1981, a bombing of the office of the Islamic Republic Party by People's Mujahedin of Iran resulted in the death of around 70 high-ranking officials, cabinet members and members of parliament, including Mohammad Beheshti, the secretary-general of the party and head of the Islamic Party's judicial system. Mohammad Javad Bahonar then became the secretary-general of the party, but was in turn assassinated on September 2. Because of these events and other assassinations the Islamic Party was weakened in 1981. It was dissolved in 1987.[143]

Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps

[edit | edit source]The Revolutionary Guard or Pasdaran-e Enqelab, was established by a decree issued by Khomeini on May 5 1979 "to protect the revolution from destructive forces and counter-revolutionaries,`[144] i.e. as a counterweight both to the armed groups of the left, and to the Iranian military, which had been part of the Shah's power base. 6,000 persons were initially enlisted and trained,[145] but the guard eventually grew into "a full-scale" military force "with air force and navy branches". Its work involves both conventional military duties, helping Islamic forces abroad, such as Hezbollah in Lebanon, and internal security, such as the suppression of narcotics trafficking, riots by the discontented, and unIslamic behavior by members of the public.[146] It has been described as "without a doubt the strongest institution of the revolution"[147]

Oppressed Mobilization

[edit | edit source]"Oppressed mobilization" or Baseej-e Mostaz'afin was founded at the command of Khomeini in 1980, to be organized by the Revolutionary Guard.[148] Its purpose was to mobilize volunteers of many skills -- doctors, engineers, but primarily to mobilize those too old or young[149] to serve in other bodies. Baseej (also Basij) often provided security, and helped police and the army. Baseej were also used to attack opposition demonstrators and ransack opposition newspaper offices, who were believed to be enemies of the revolution..[150]

Hezbollah

[edit | edit source]The Hezbollah or Party of God, were the "strong-arm thugs" who attacked demonstrators and offices of newspapers critical of Khomeini, and later a wider variety of activities found to be undesirable for "moral" or "cultural" reasons.[151] Hezbollah is/was not a tightly structured independent organisation but more a movement of loosely bound groups usually centered around a mosque.[152] Although in the early days of the revolution Khomeinists -- those in the Islamic Republican Party -- denied connection to Hezbollah, maintaining its attacks were the spontaneous will of the people over which the government had no control, in fact Hezbollah was supervised by "a young protegee of Khomeini," Hojjat al-Islam Hadi Ghaffari.[153]

Jihad of Construction

[edit | edit source]Jihad of construction, or Jahad-e Sazandegi, began as a movement of "volunteers to help with the 1979 harvest", but soon took on a "broader, more official role" in the countryside. It is involved with "road building, piped water, electrification, clinics, schools, and irrigation canals."[154] It also provides "extension services, seeds, loans," etc. to small farmers[155] Finally it was merged with agriculture ministry in 2001 to form the Ministry of Jihad-e-Agriculture.[156]

The Islamic republic

[edit | edit source]Khomeini takes power

[edit | edit source]There was great jubilation in Iran at the ousting of the Shah, but the glue that stuck together the dozens of religious, liberal, secularist, Marxist, and Communist, revolutionary factions—opposition to the Shah—was now gone. Each of the many groups vying for influence had different interpretations of the broad goals of the revolution: an end to tyranny, more Islamic and less American and Western influence, more social justice and less inequality.

Khomeini had "overwhelming ideological, political and organizational hegemony,"[157] but this was in large part because his non-theocratic allies believed he had neither the interest in nor ability to rule,[158] and intended to be more a spiritual guide than a power holder. Khomeini was in his mid-70s, had never held public office, been out of Iran for more than a decade, and had told questioners things like "the religious dignitaries do not want to rule,"[159][160]

There is some dispute over whether "what began as an authentic and anti-dictatorial popular revolution based on a broad coalition of all anti-Shah forces was soon transformed into an Islamic fundamentalist power-grab"[161] after the return of Khomeini, or whether the non-theocratic groups played a role in the early days of the revolution, but did not seriously challenge Khomeini's movement in popular support.[162] Whichever was the case, Khomeini's forces prevailed, eliminating with skillful timing both adversaries and unwanted allies from power[163] and implemented his wilayat al-faqih design for an Islamic Republic led by himself as Supreme Leader.[164]

In the first year of revolution there were two centers of power: the Provisional Revolutionary Government, and the revolutionary organizations. Foundation of revolutionary organizations and councils was begun by leadership of Ayatollah Khomeini. These official and popular organizations managed revolutionary situation and established new Islamic state.

Establishment of Islamic republic government

[edit | edit source]Referendum of 12 Farvardin

[edit | edit source]On March 30 and 31 (Farvardin 10, 11) Iranians voted on whether Iran should become an "Islamic Republic," . On Farvardin 12 a 98.2% vote in favor was announced, with Khomeini declaring the result a victory of "the oppressed ... over the arrogant."[165] Several secularist and communist groups boycotted the vote but turnout was very high. The opposition claims Islamic Republic not being defined.

Assembly of Experts of Constitution

[edit | edit source]The seventy-three-member Assembly of Experts for Constitution was elected in the summer of 1979 to write a new constitution for the Islamic Republic. The Assembly was originally conceived of as a way expediting the draft constitution which Khomeini supporters had started working when Khomeini was still in exile, but which leftists found too conservative and wanted to make major changes to. Ironically, it was the Assembly that made major changes, instituting principles of theocracy by velayat-e faqih, adding on a faqih Supreme Leader, and increasing the power and clerical character of the Council of Guardians which could veto un-Islamic legislation. The new constitution was opposed by some clerics, including Ayatollah Shariatmadari, and secularists who urged a boycott. It was approved by referendum on December 2 and 3, 1979, by over 98 percent of the vote.[166]

Post-revolutionary Parties and movements

[edit | edit source]Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line

[edit | edit source]Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line was a group of student supporters of Khomeini that occupied the U.S. embassy in Tehran on 4 November 1979 after the ex-Shah of Iran was admitted to the United States for cancer treatment. Although the students later said they did not expect to occupy the embassy for long, their action received official support and triggered the Iran hostage crisis where 52 American diplomats were held hostage for 444 days. (see below)

Consolidation of power by Khomeini

[edit | edit source]The Khomeini-appointed Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan supported the establishment of a reformist, democratic parliamentary government.[167] Operating separately were the Revolutionary Council made up of Khomeini and his clerical supporters, the Revolutionary Guards, revolutionary tribunals, and at the local level revolutionary cells turned local committees (komitehs).[168] While the moderate Bazargan and his Provisional Revolutionary Government (temporarily) reassured the Westernized middle class, it became apparent they did not have power over the "Khomeinist" revolutionary bodies, particularly the Revolutionary Council and later the Islamic Revolutionary Party. Inevitably the overlapping authority of the Revolutionary Council (which had the power to pass laws) and Revolutionary government was a source of conflict,[169] despite the fact that both had been approved by and/or put in place by Khomeini.

In June, the Freedom Movement released its draft constitution; it referred to Iran as an Islamic Republic and included a Guardian Council to veto unIslamic legislation, but had no guardian jurist ruler.[170] The constitution was sent for review to the newly-elected Assembly of Experts for the Constitution which was dominated by allies of Khomeini. Despite the fact that Khomeini had originally declared it ‘correct’,[171][160] Khomeini (and the assembly) rejected the constitution, Khomeini declaring that the new government should be based "100% on Islam."

A new constitution drawn up by the Assembly of Experts for the Constitution created a powerful post of Supreme Leader for Khomeini, [9] who was in charge of the military and security services, and appointed several top government and judicial officials. A less powerful president was to be elected every four years. Another theocratic body, the Council of Guardians) was given veto power over candidates for president, parliament, and the body that elected the Supreme Leader (the Assembly of Experts) as well as laws passed by the legislature.

Hostage Crisis

[edit | edit source]In October 1979 the United States admitted the exiled and ailing Shah into the country for cancer treatment. There was an immediate outcry in Iran with both Khomeini and leftist groups demanding the Shah's return to Iran for trial and execution. Revolutionaries were reminded of Operation Ajax, 26 years earlier when the Shah fled abroad while American CIA and British intelligence organized a coup d'état to overthrow his nationalist opponent.

Youthful supporters of Khomeini, calling themselves Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line invaded the embassy compound and took 52 American hostages at the American embassy, in what became known as the Iran hostage crisis. Khomeini supported the hostage-taking not only out of his enmity for the ex-Shah but to advance the cause of theocratic government and outflank his opponents, or as he told his future President, "This action has many benefits. ... This has united our people. Our opponents do not dare act against us. We can put the constitution to the people's vote without difficulty, and carry out presidential and parliamentary elections."[172] The anti-theocratic liberals who opposed keeping the hostages split from anti-theocratic leftist guerilla organizations who supported it.

Attempts to extradite the Shah for execution were unsuccessful. The Shah left America for Egypt, where he had been given exile by Pres. Anwar Sadat, and where he died less than a year after the hostage taking. This, however, did not end the crisis which switched focus to the American embassy being a "nest of spies". Embassy documents were released by Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line showing moderates had met with U.S. officials, although similar evidence of high ranking Islamists having also done so did not see the light of day.[173]

While the final settlement that released the hostages "did not meet any of Iran's original demands" and was considered "almost wholly favorable to the United States",[174] the crisis did succeed in radicalizing the revolution and further weakening Iranian moderates. Among the moderate causualties of the hostage crisis was Prime Minister Bazargan who resigned in November unable to enforce the government's order to release the hostages.[175] Another legacy was the weakening of the Iranian economy from economic sanctions placed on Iran by America which are still in place.[176][177]

Opposition to the revolution

[edit | edit source]Iranian dissent and its suppression

[edit | edit source]| A Wikibookian questions the neutrality of this page. You can help make it neutral, request assistance, or view the relevant discussion. |

The first to be executed by revolutionary leadership were members of the old regime: senior generals, and a couple of months later over 200 of the Shah's senior civilian officials[178] as punishment and to eliminate the danger of coup d’État. Brief trials lacking defense attorneys, juries, transparency or opportunity for the accused to defend themselves[179] were held by revolutionary judges such as Sadegh Khalkhali, the Sharia judge. Among those executed was Amir Abbas Hoveida, former Prime Minister of Iran. Those who escaped Iran were not immune. A decade later, another former Prime Minister, Dr. Shapour Bakhtiar, was assassinated in Paris, one of at least 63 Iranians abroad killed or wounded since the Shah was overthrown,[180] although these attacks are thought to have stopped after the early 1990s.[181]

Communist guerrillas and federalist parties revolted in some regions comprising Khuzistan, Kurdistan and Gonbad-e Qabus which resulted in fighting among them and revolutionary forces. These revolts began in April and lasted for several months or years depending on the region.

By early March revolutionaries hoping for a government based on liberal democracy were given a taste of disappointments to come when Khomeini announced "Do not use this term, ‘democratic.’ That is the Western style."[182] In mid August several dozen newspapers and magazines opposing Khomeini's idea of Islamic government — theocratic rule by jurists or velayat-e faqih — were shut down.[183][184] Khomeini angrily denounced protests against the press closings, saying "we thought we were dealing with human beings. It is evident we are not."[185] Half a year later the moderate opposition Muslim People's Republican Party was suppressed with many of the aides of its elderly figurehead, the Grand Ayatollah Shari'atmadari, put under house arrest.[186] In March 1980 the "Cultural Revolution" began. Universities, a leftist bastion, were closed for two years to purge them of opponents to theocratic rule. In July the state bureaucracy began the dismissal of 20,000 teachers and nearly 8,000 military officers deemed too "Westernized"[187]

Khomeini sometimes used takfir (declaring someone guilty of apostasy, a capital crime) to deal with his opponents. When leaders of the National Front party called for a demonstration in mid-1981 against a new law on qesas, or traditional Islamic retaliation for a crime, Khomeini threatened its leaders with the death penalty for apostasy "if they did not repent."[188]

One of the last organized opponents of theocratic rule was the People's Mujahedin of Iran, a guerrilla group that unlike most of the opposition was armed and accustomed to using violence. In February 1980 concentrated attacks by hezbollahi toughs began on the meeting places, bookstores, newsstands of Mujahideen and other leftists[189] driving the left underground. People's Mujahideen retaliated with a campaign of bombing assassination including the killing of 72 at the Islamic Republican Party headquarters on June 28, 1981[190] President Mohammad Ali Rajai and Prime Minister Mohammad Javad Bahonar were also assassinated that year.[191]

Neighboring regimes and the Iran-Iraq War

[edit | edit source]The Islamic Republic positioned itself as a revolutionary beacon under the slogan "neither East nor West" (i.e. follow neither Soviet nor American/West European models), and called for the overthrow of capitalism, American influence, and social injustice in the Middle East and the rest of the world. Revolutionary leaders in Iran gave and sought support from non-Islamic as well as Islamic Third World causes — e.g. the PLO, Sandinistas in Nicaragua, Irish IRA and anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa — even to the point of favoring non-Muslim revolutionaries over more conservative Islamic causes such as the neighboring Afghan Mujahideen.[192]

In its region, Iranian Islamic revolutionaries called specifically for the overthrow of monarchies and their replacement with Islamic republics, much to the alarm of its smaller Sunni-run Arab neighbors Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf States. Most of these countries were monarchies and all had sizable Shi'a populations - including a majority population in Iraq and Bahrain. In 1980, Iraq whose government was Sunni Muslim and Arab nationalist, invaded Iran in an attempt to seize the oil-rich predominantly Arab province of Khuzistan and destroy the revolution in its infancy. Thus began the eight year Iran-Iraq War, one of the most destructive and bloody wars of the 20th century.

A combination of fierce patriot resistance by Iranians and military incompetence by Iraqi forces soon stalled the Iraqi advance and by early 1982 Iran regained almost all the territory lost to the invasion. The invasion rallied Iranians behind the new regime, and past differences were largely abandoned in the face of the external threat. The war also became an opportunity for the regime to crush its remaining opponents, mostly the Soviet-backed leftist groups, dishing out harsh treatment, including torture and imprisonment.

Realizing its mistake, the Iraqis offered Iran a truce. Khomeini rejected it, announcing the only condition for peace was that "the regime in Baghdad must fall and must be replaced by an Islamic Republic."[193] The war continued for another six years with hundreds of thousands of lives lost and great destruction from air attacks. While in the end the revolutionaries failed to expand the Islamic revolution into Iraq, they did solidify their control of Iran.[194]

Post-revolutionary impact

[edit | edit source]International

[edit | edit source]Internationally, the initial impact of the Islamic revolution was immense. In the non-Muslim world it has changed the image of Islam, generating much interest in the politics and spirituality of Islam.[195] In the Mideast and Muslim world, particularly in its early years, it triggered enormous enthusiasm and redoubled opposition to western intervention and influence. Islamist insurgents rose in Saudi Arabia (the 1979 week-long takeover of the Grand Mosque), Egypt (the 1981 machine-gunning of the Egyptian President Sadat), Syria (the Muslim Brotherhood rebellion in Hama), and Lebanon (the 1983 bombing of the American Embassy and French and American peace-keeping troops).[196]

Although ultimately these rebellions did not succeed, other activities have had more long term impact. The Ayatollah Khomeini's 1989 fatwa calling for the killing of Salman Rushdie for his allegedly blasphemous book The Satanic Verses, demonstrated that even citizens of a foreign country living in that country were not safe from the long arm of the Islamic revolution. The Islamic revolutionary government itself is credited with financing and helping create such groups as the powerful Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq and the United Islamic Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan. In Lebanon, Iran's generous financing of Hezbollah helped establish that group as a major political and military power which fought against Israeli occupation and its proxy South Lebanon Army, and expanded Shia Islam's influence.[197] Hezbollah's dependence on Iran for military and financial aid is heavily debated, and the Israel-Hezbollah 2006 War provided an eye-opening for the world of Hezbollah weapons said to be Iranian imports.[198][199]

The revolution has won praise from some Muslim leaders. Hamas Palestinian Prime Minister Ismail Haniyeh:

You are also continuing the same path that was initiated by Imam Khomeini, since you have always supported the Palestinian people, and I hope that we will meet each other at the Al-Aqsa Mosque in the near future.[200]

Others have been less complementary. Scholars have argued the devastating Iran-Iraq "mortally wounded ... the ideal of spreading the Islamic revolution,"[201] or that Iran has lost "its place as a great regional power,"[202] because the ideology of the revolution prevents Iran from following a "nationalist, pragmatic" foreign policy. Others say the only country outside Iran the revolution has had a "measure of lasting influence" is in Lebanon.[203]

Iranians have also complained of the international impact on individual citizens. As one complained to an Iranian-American journalist: "What has come of us. Our currency is worthless. Those backward Arabs go to Europe with rials, and we can barely visit Turkey with our worthless tomans!" [204]

Energy Crisis

[edit | edit source]

The revolution shattered the Iranian oil sector and the loss of output led to the 1979 international energy crisis.

Domestic

[edit | edit source]| A Wikibookian questions the neutrality of this page. You can help make it neutral, request assistance, or view the relevant discussion. |

Internally, some goals of the revolutionary — broadening education and health care for the poor, and particularly governmental promotion of Islam, and the elimination of secularism and American influence in government — have met with unqualified successes; others — such as greater political freedom, governmental honesty and efficiency, economic equality and self-sufficiency, and even popular religious devotion[206] — have not.[207] Overall, however, dissatisfaction is widespread.

Human development

[edit | edit source]One of the highlights of the revolution has been an increase in literacy. Although the Shah's regime had created a popular and successful Literacy Corps and also worked to raise literacy rates,[208] the Islamic Republic based its educational reforms on Islamic principles. A few months after the victory of the Islamic Revolution, a decree was issued by Ayatollah Khomeini to establish the Literacy Movement Organization (LMO), with the primary objective of providing literacy courses for the illiterate population through a vast mobilization program.[209] Designed especially for those who never learned to read and write, the program is credited with much of the country's success in reducing illiteracy from 52.5 per cent in 1976 to just 24 per cent, at the last count in 2002.[210] The movement has established over 2,000 community learning centers across the country, employed some 55,000 instructors, distributed 300 easy-to-read books and manuals, and provided literacy classes to a million people, men as well as women.[211][212]

In the field of health, maternal and infant mortality rates have been slashed.[213] Population growth was encouraged for the first nine years of the revolution,[214] but in 1988 youth unemployment concerns prompted the government to do "an amazing U-turn" and Iran now has "one of the world's most effective" family planning programs.[215] Overall, Iran's Human development Index rating has climbed significantly from 0.569 in 1980 to 0.732 in 2002, on par with neighbour Turkey. [216] [217]

Political freedom

[edit | edit source]Iran has elected governmental bodies at the national, provincial and local levels for which all males and females from the age of 15 on up may vote. (See Politics and Government of Iran) Although these bodies are subordinate to theocracy — which has veto power over who can run for parliament (or Islamic Consultative Assembly) and whether its bills can become law — they have more power than equivalent organs under the Shah's regime. Four of the 290 parliamentary seats are allocated for the minority Christian (3 seats), Jewish (1 seat) and Zoroastrian (1 seat) communities in rough proportion with their population[218] — giving at least token acknowledgment of individual or minority rights.[219] Khomeini met with the Jewish community upon his return from exile in Paris and issued a fatwa decreeing that the Jews were to be protected. Similar edicts also protect Iran's tiny Christian minority.[220]

Religious minorities

[edit | edit source]On the other hand, religious minorities in Iran complain of discrimination, particularly the members of the Bahá'í Faith, which has been declared heretical. More than 200 Bahá'ís have been executed or killed, hundreds more have been imprisoned, and tens of thousands have been deprived of jobs, pensions, businesses, and educational opportunities. All national Bahá'í administrative structures have been banned by the government, and holy places, shrines and cemeteries have been confiscated, vandalized, or destroyed. In March 2006, a United Nations report informed the world that Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamene’i has instructed a number of government agencies, including the revolutionary guard and the police force, to 'collect any and all information about members of the Bahá'í Faith'.[221]

Political repression

[edit | edit source]Political repression has been a major complaint against the Islamic Republic. Grumbling once done about the tyranny and corruption of the Shah and his court is now directed against "the Mullahs."[222] Fear of SAVAK has been replaced by fear of Revolutionary Guards, and other religious revolutionary enforcers.[223] Violations of human rights by the theocratic regime is said by some to be worse than during the monarchy,[224] and in any case extremely grave.[191] Torture, the imprisoning of dissidents, and the murder of prominent critics is commonplace. Censorship is handled by the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance, without whose official permission, "no books or magazines are published, no audiotapes are distributed, no movies are shown and no cultural organization is established."[225]

Women

[edit | edit source]The impact on women of the revolution has been particularly mixed. One of the striking features of the revolution was the large scale participation of women — from traditional backgrounds — in demonstrations.[226] Some of this liberating effect has continued. Female university enrollment has risen steadily, reaching 66% in 2003.[227] There are large numbers of women in the civil service and higher education, one example being the 14 women who were elected to the Islamic Consultative Assembly in 1996. On the other hand, the Islamic revolution is ideologically committed to inequality for women in inheritance and other areas of the civil code; and especially committed to segregation of the sexes. Many places, from "schoolrooms to ski slopes to public buses", are strictly segregated. Females caught by revolutionary officials in a mixed-sex situation can be subject to virginity tests.[228] "Bad hijab" ― exposure of any part of the body other than hands and face — is subject to punishment of up to 70 lashes or 60 days imprisonment.[229][230]

Economy

[edit | edit source]Iran's economy has not prospered. Dependence on petroleum exports is still strong. [231] Per capita income, which fluctuates with the price of oil, has fallen by one estimate to as low as 1/4 of what it was during the Shah's era [232][233] and is still less than it was before the revolution. Unemployment among Iran's population of young has steadily risen as job creation has failed to keep up,[234] a high level of corruption being blamed in part.[235][234]

Gharbzadegi ("westoxification") or western cultural influence stubbornly remains, brought by music recordings, videos, and satellite dishes.[236] One post-revolutionary opinion poll found 61% of students in Tehran chose "Western artists" as their role models with only 17% choosing "Iran's officials."[237]

Further reading

[edit | edit source]- Afshar, Haleh, ed. (1985). Iran: A Revolution in Turmoil. Albany: SUNY Press. ISBN 0-333-36947-5.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Barthel, Günter, ed. (1983). Iran: From Monarchy to Republic. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. <!— ISBN ?? —>.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Daniel, Elton L. (2000). The History of Iran. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30731-8.

- Esposito, John L., ed. (1990). The Iranian Revolution: Its Global Impact. Miami: Florida International University Press. ISBN 0-8130-0998-7.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Harris, David (2004). The Crisis: The President, the Prophet, and the Shah — 1979 and the Coming of Militant Islam. New York & Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-32394-2.

- Hiro, Dilip (1989). Holy Wars: The Rise of Islamic Fundamentalism. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-90208-8. (Chapter 6: Iran: Revolutionary Fundamentalism in Power.)

- Kapuściński, Ryszard. Shah of Shahs. Translated from Polish by William R. Brand and Katarzyna Mroczkowska-Brand. New York: Vintage International, 1992.

- Kurzman, Charles. The Unthinkable Revolution. Cambridge, MA & London: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Ladjevardi, Habib (editor), Memoirs of Shapour Bakhtiar, Harvard University Press, 1996.

- Legum, Colin, et al., eds. Middle East Contemporary Survey: Volume III, 1978–79. New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers, 1980. + *Legum, Colin, et al., eds. Middle East Conte

- Milani, Abbas, The Persian Sphinx: Amir Abbas Hoveyda and the Riddle of the Iranian Revolution, Mage Publishers, 2000, ISBN 0-934211-61-2.

- Munson, Henry, Jr. Islam and Revolution in the Middle East. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988.

- Nafisi, Azar. "Reading Lolita in Tehran." New York: Random House, 2003.

- Nobari, Ali Reza, ed. Iran Erupts: Independence: News and Analysis of the Iranian National Movement. Stanford: Iran-America Documentation Group, 1978.

- Nomani, Farhad & Sohrab Behdad, Class and Labor in Iran; Did the Revolution Matter? Syracuse University Press. 2006. ISBN 0-8156-3094-8

- Pahlavi, Mohammad Reza, Response to History, Stein & Day Pub, 1980, ISBN 0-8128-2755-4.

- Rahnema, Saeed & Sohrab Behdad, eds. Iran After the Revolution: Crisis of an Islamic State. London: I.B. Tauris, 1995.

- Sick, Gary. All Fall Down: America's Tragic Encounter with Iran. New York: Penguin Books, 1986.

- Shawcross, William, The Shah's last ride: The death of an ally, Touchstone, 1989, ISBN 0-671-68745-X.

- Smith, Frank E. The Iranian Revolution. 1998.

- Society for Iranian Studies, Iranian Revolution in Perspective. Special volume of Iranian Studies, 1980. Volume 13, nos. 1–4.

- Time magazine, January 7, 1980. Man of the Year (Ayatollah Khomeini).

- U.S. Department of State, American Foreign Policy Basic Documents, 1977–1980. Washington, DC: GPO, 1983. JX 1417 A56 1977–80 REF - 67 pages on Iran.

- Yapp, M.E. The Near East Since the First World War: A History to 1995. London: Longman, 1996. Chapter 13: Iran, 1960–1989.

- Freddy Eytan " France and the Iranian Revolution" [10]

References and notes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Islamic Revolution, Iran Chamber.

- ↑ Islamic Revolution of Iran, MS Encarta.

- ↑ The Islamic Revolution, Internews.

- ↑ Iranian Revolution.

- ↑ Iran Profile, PDF.

- ↑ The Shah and the Ayatollah: Iranian Mythology and Islamic Revolution (Hardcover), ISBN 0-275-97858-3, by Fereydoun Hoveyda, brother of Amir Abbas Hoveyda.

- ↑ An [[w:w:Iranian monarchy|]] is the kind of monarchy Iran was.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Marvin Zonis quoted in Wright, Sacred Rage, 1996, p.61

- ↑ Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, (2006), p.121

- ↑ The Iranian Revolution.

- ↑ [[w:w:Supreme Leader|]]

- ↑ Ruhollah Khomeini, Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ Iran Islamic Republic, Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ Amuzegar, The Dynamics of the Iranian Revolution, (1991), p.4, 9-12

- ↑ Arjomand, Turban (1988), p. 191.

- ↑ Amuzegar, Jahangir, The Dynamics of the Iranian Revolution, SUNY Press, p.10

- ↑ Harney, Priest (1998), p. 2.

- ↑ Abrahamian Iran (1982), p. 496.

- ↑ [[w:w:Guardianship of the Islamic Jurists|]]

- ↑ [[w:w:Qom|]] is a city in Iran.

- ↑ Benard, "The Government of God" (1984), p. 18.

- ↑ Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, "As Soon as Iran Achieves Advanced Technologies, It Has the Capacity to Become an Invincible Global Power," 9/28/2006 Clip No. 1288.

- ↑ Shirley, Know Thine Enemy (1997), pp. 98, 104, 195.

- ↑ Akhbar Ganji talking to Afshin Molavi. Molavi, Afshin, The Soul of Iran, Norton paperback, (2005), p.156.

- ↑ Mackay, Iranians (1998), pp. 259, 261.

- ↑ a b c Khomeini's speech against capitalism, IRIB World Service. Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Khomeini" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Brumberg, Reinventing Khomeini (2001).

- ↑ Shirley, Know Thine Enemy (1997), p. 207.

- ↑ Mackay, Iranians (1998), pp. 236, 260.

- ↑ Harney, The Priest (1998), pp. 37, 47, 67, 128, 155, 167.

- ↑ Taheri, The Spirit of Allah (1985), p. 136.

- ↑ Arjomand Turban (1998), p. 192.

- ↑ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 178.

- ↑ Hoveyda Shah (2003) p. 22.

- ↑ Abrahamian, Iran (1982), pp. 533–4.

- ↑ Mackay, Iranians (1998), p. 219.

- ↑ Katouzian (1981), The Political Economy of Modern Iran: Despotism and Pseudo-Modernism, 1926–1979.

- ↑ Kapuscinski, Shah of Shahs (1985).

- ↑ a b c Taheri, The Spirit of Allah (1985) pp. 234–5.

- ↑ Harney, The Priest (1998), p. 65.

- ↑ Graham, Iran (1980), pp. 19, 96.

- ↑ Abrahamian, Iran Between Two Revolutions (1982) pp. 442–6.

- ↑ Taheri, The Spirit of Allah (1985) p. 205.

- ↑ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 188.

- ↑ Graham, Iran (1980) p. 231.

- ↑ Graham, Iran (1980) p. 228.

- ↑ Harney, The Priest (1998).

- ↑ a b Graham, Iran (1980), p. 235.

- ↑ Arjomand, Turban (1998), pp. 189–90.

- ↑ Taheri, The Spirit of Allah (1985), p. 233.

- ↑ Schirazi, The Constitution of Iran (1997), pp. 293–4.

- ↑ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 200.

- ↑ Brumberg, Reinventing Khomeini (2001), pp. 44, 74–5.

- ↑ Taheri, The Spirit of Allah (1985), p. 238.

- ↑ Harney, The Priest (1998), p. 177.

- ↑ Graham, Iran (1980) p. 233.

- ↑ Zabih, Iran (1982), p. 16.

- ↑ a b Mackay, Iranians (1996) pp. 215, 264–5.

- ↑ Keddie, Modern Iran, (2003) p.201-7

- ↑ The Last Great Revolution Turmoil and Transformation in Iran, by Robin WRIGHT.

- ↑ Dabashi, Theology of Discontent (1993), p.419, 443

- ↑ Khomeini; Algar, Islam and Revolution, p.52, 54, 80

- ↑ See: Velayat-e faqih (book by Khomeini)#Importance_of_Islamic_Government

- ↑ khomeinism

- ↑ Abrahamian Iran(1982), p.478-9

- ↑ Amuzegar, Dynamics of the Iranian Revolution (1991), p.10

- ↑ Schirazi, Constitution of Iran (1997) p.29-32

- ↑ See: Hokumat-e Islami : Velayat-e faqih (book by Khomeini)#Why_Islamic_Government_has_not_been_established

- ↑ Khomeini and Algar, Islam and Revolution (1981), p.34

- ↑ http://www.worldstatesmen.org/Iran_const_1906.doc

- ↑ Rajaee, Farhang, Islamic Values and World View: Farhang Khomeyni on Man, the State and International Politics, Volume XIII (PDF), University Press of America. ISBN 0-8191-3578-X

- ↑ a b Kapuściński, Ryszard. Shah of Shahs. Translated from Polish by William R. Brand and Katarzyna Mroczkowska-Brand. New York: Vintage International, 1992.

- ↑ Nehzat by Ruhani vol. 1 p. 195, quoted in Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 75.

- ↑ Islam and Revolution, p. 17.

- ↑ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 112.

- ↑ Graham, Iran 1980, p. 69.

- ↑ Taheri, The Spirit of Allah (1985), p. 196.

- ↑ Graham, Iran (1980), p. 213.

- ↑ Hiro, Dilip. Iran Under the Ayatollahs. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. 1985. p. 57.

- ↑ Wright, Last (2000), p. 220.

- ↑ Graham, Iran (1980) p. 94.

- ↑ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 174.

- ↑ Graham, Iran (1980), p. 96.

- ↑ Abrahamian, Iran (1982), p. 444.

- ↑ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 163.

- ↑ Graham, Iran (1980), p. 226.

- ↑ Abrahamian, Iran (1982), pp. 501–3.

- ↑ Moin, Khomeini (2000), pp. 183–4.

- ↑ Moin, Khomeini (2000), pp. 184–5.

- ↑ Taheri, Spirit (1985), pp. 182–3.

- ↑ "Ideology, Culture, and Ambiguity: The Revolutionary Process in Iran", Theory and Society, Vol. 25, No. 3 (Jun., 1996), pp. 349–88.

- ↑ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p.80

- ↑ Abrahamian, Iran Between (1980), pp. 502–3.

- ↑ Mackay, Iranians (1996), p. 276.

- ↑ Abrahamian, Iran Between (1980), pp. 478–9

- ↑ Abrahamian, Iran (1982), p. 505.

- ↑ Mackey, Iranians (1996) p. 279.

- ↑ Harney, The Priest (1998), p. 14.

- ↑ Abrahamian, Iran (1982), pp. 510, 512, 513.

- ↑ Abrahamian, Iran (1982), p. 498–9.

- ↑ Keddie, Modern Iran (2003), p. 235.

- ↑ Keddie, Modern Iran (2003), pp. 235–6.

- ↑ Shawcross, The Shah's Last Ride (1988), p. 21.

- ↑ Keddie, Modern Iran (2003), p. 235.

- ↑ Amuzegar, Jahangir, Dynamics of Iranian Revolution: The Pahlavis' Triumph and Tragedy SUNY Press, (1991) p.4, 21, 87

- ↑ Taheri, Spirit (1985) p. 220.

- ↑ In a recent book by Hossein Boroojerdi, called "Islamic Revolution and its roots", he claims that Cinema Rex was set on fire using chemical material provided by his team operating under the supervision of "Hey'at-haye Mo'talefe (هیأتهای مؤتلفه)", an influential alliance of religious groups who were among the first and most powerful supporters of Ayatollah Khomeini.

- ↑ Moin, Khomeini (2000), p. 187.

- ↑ W. Branigin, ‘Abadan Mood Turns Sharply against the Shah,’ Washington Post, 26, August 1978