Issues in Interdisciplinarity 2018-19/Evidence for the Implications of the Cow in India

| This is the print version of Issues in Interdisciplinarity 2018-19 You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

The current, editable version of this book is available in Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection, at

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Issues_in_Interdisciplinarity_2018-19

Disciplinary Categories and Reframing Deforestation in Guinea

This chapter aims to explore how disciplinary categories can create knowledge borders, leading to a lack of information flow within problem-solving, and how hierarchy among disciplinary categories might lead to the assumption that one certain solution is best.

Disciplinary categories can be applied to a variety of contexts, therefore its precise meaning will naturally vary. As a working definition for this chapter, we understand disciplinary categories to be the bordered fields of academia.[1] For example, mathematics and anthropology are different disciplinary categories. The rigidity and distinction in academic disciplines are intrinsic in its etymology, and these characteristics can lead to disregarding ideas that oppose the accepted canon.[2]

Thus, there is frequently a lack of interaction between different disciplines, especially in policy-making. This prevents us from reaching holistic conclusions when thinking about real-world problems.

To present these issues of disciplinary categorisation in context, we will discuss a case study regarding environmental conservation in Guinea based on the research of Leach and Fairhead. It is a piece of interdisciplinary work exploring the previous absence of communication between disciplines, which led to essential evidence being omitted or misinterpreted, hence forming impartial conclusions.

This chapter will then draw out some key issues regarding disciplinary categories and their interactions in solving issues, in relation to this case study.

Case study

[edit | edit source]

Leach and Fairhead's research took place in Kissidougou; a city located in Guinea's savanna-forest transition zone,[3] which was believed to be undergoing a deforestation crisis.[4]

Administrators and ecologists have maintained that forest cover in Guinea had significantly reduced since 1995.

Pieces of evidence predominantly provided by scientific disciplines, have formed a narrative with limited perspectives. Through extensive mathematical modelling and ecological analysis, policymakers and scientists established the change in the lifestyles and land use of the Kissidougou people, along with population growth,[5] to be the primary reasons of deforestation there. Their research included identification of certain species of trees and other forms of vegetation, that are typically found in the outskirts of forest patches, which led to experts concluding that deforestation had occurred.[3]

Leach and Fairhead challenged this by conducting research alongside existing data encompassing several disciplines such as history, economics, archaeology and anthropology, revealing that the emergence of these variant forest patches was primarily due to intervention by local communities,[5] rather than as a result of deforestation.

The pair spoke to villagers about the history of the Kissidougou and consulted aerial photographs that showed the area's vegetation history.[6] The data not only revealed that there actually was an increase in forest patches, but also proved that the 'rapid population growth causing deforestation' narrative was unfounded. Through analysing broader regional history, anthropological evolution, and archaeology, they found that certain areas had significantly higher rural populations in the 19th century than in 1995.[5] Therefore, when viewing the problem through an interdisciplinary lens, it becomes apparent that the change in population demographics did not result in degradation.

The researchers also included socioeconomic analysis of Kissidougou's population to explain how their activities impacted the vegetation in the area. The villagers had adapted the land to suit changing socioeconomic conditions. They switched from coffee planting to fruit tree planting after the post-colonial period, due to falling prices, and this helped nurture the creation of the forest patches.[5]

It is clear from this case study that a more appropriate solution can be reached considering evidence from other disciplinary categories.

A question to consider is whether the research of academic disciplines that are seemingly more objective or use quantitative data, tend to naturally be more conducive to policy-making. Difficulties arise from assessing the weight of quantitative data from some disciplines against the qualitative of others. The quality of objectivity might give leverage to 'inform policies to address [issues]', compared to other disciplinary categories that may hold other perspectives.[7] By calculating the loss of forest cover mathematically and using these figures to drive a decision to impose policies, we neglect the understanding of important cultural values and livelihoods of locals.[7]

Range of research methodology among academic disciplines

[edit | edit source]Data is essential in solving real-world problems, but different academic disciplines are anchored to different methods of collecting data. This can lead to differing evidence, and perhaps then a different truth and approach to solving the same issue. Research methodologies include interviews, content analysis, focus groups and language-based analysis to name a few.[8] This becomes a problem in interdisciplinary work, when disciplines disagree about the way that research is being conducted.

However, as exemplified by the case study of deforestation in Kissidougou, by integrating viewpoints from other disciplines in discussions about how research should be conducted for particular issues, it can help highlight weaknesses of the research and factors it may be neglecting in the methodology.[2]

Communication between and perceived hierarchy among disciplines

[edit | edit source]An issue that should be addressed whilst incorporating multiple disciplines into solving an issue is how they will interact. Academic disciplines can be seen as communities, with ‘distinctive cultural characteristics’ and ‘cultural differences’. Tony Becher, a professor at the University of Sussex, writes that 'disciplinary groups can usefully be regarded as academic tribes, each with their own set of intellectual values and their own patch of cognitive territory'.[9]

Research integrating both quantitative and qualitative methods is becoming increasingly common. A solution to overcoming the borders of academic disciplinary research is employing overall designed systems for mixed-method research, named ‘typologies'. However many of these have been constructed in theoretical terms and are yet to be tested in real-world examples. These typologies draw attention to questions such as: which has priority, the qualitative or quantitative data? Is there more than one data strand? Are the types of data from each discipline collected simultaneously or sequentially?[8]

It is often the case that some disciplinary categories tend to 'dominate’ in terms of their input on a range of issues, according to a hierarchical structure.[10] This is dependent on what kinds of particular perspectives are reinforced, usually by authoritative bodies. Placing a greater weight on viewpoints from a certain discipline can lead to disregarding those derived from other disciplines. This was observed in the case study on Kissidougou, where mathematical and ecological perspectives were primarily considered and supported by policymakers, but perspectives from anthropology and history were overlooked.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]As a counter-point to the advocacy of interdisciplinarity in solving complex issues, it might be that not all issues benefit from working across disciplines. What is important, however, is that academic disciplines are subjected to scrutiny from alternative approaches and disciplines. Encouraging communication and opening up a dialogue will always be beneficial.[2]

As seen from the case study, there becomes a need to pull research out of disciplinary silos to solve complex problems more holistically.[11] By travelling over the borders of academic disciplines, regardless of differences in methodologies, terminology and evidence, greater validity and a more comprehensive account of an area of inquiry can be reached.[8] This can open the doors to new solutions, which incorporates crucial knowledge required to initiate productive change.[12]

See also

[edit | edit source]- Academic Disciplines

- Environmental Protection

- Environmental Degradation

- Deforestation

- Landscape Ecology

- Transitional Zone

External links

[edit | edit source]- Fields of Knowledge, a zoomable map outlining different academic disciplines and their sub-sections.

- Second Nature, a documentary based on Leach and Fairhead's research in Guinea.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary. “discipline, n.”. [Internet]. [cited 2018 Nov 29]. Available from: http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/53744?rskey=F30kzg&result=1

- ↑ a b c Harriss J. The case for cross-disciplinary approaches in international development. World development. 2002;30(3):487–96.

- ↑ a b Fairhead J, Leach M. Webs of power: forest loss in Guinea. Seminar in New Delhi; 2000. p. 44–53.

- ↑ Shepherd J. Melissa Leach: Village Voice. [Internet]. The Guardian; 2007 [cited 2018 Nov 28]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2007/jul/17/highereducationprofile.academicexperts

- ↑ a b c d Fairhead J, Leach M. False Forest History, Complicit Social Analysis: Rethinking Some West African Environmental Narratives. World Development. 1995;23(6):1023-1035.

- ↑ Fairhead J, Leach M. Reading Forest History Backwards: Guinea's Forest–Savanna Mosaic, 1893–1993 [Internet]. Environmentandsociety.org; 1995 [cited 2018 Dec 5]. Available from: http://www.environmentandsociety.org/sites/default/files/key_docs/Fairhead-Leach-1-1.pdf

- ↑ a b Fairhead J, Leach M. Reframing Deforestation Global Analyses and Local Realities: Studies in West Africa. 1st ed. London: Routledge; 1998.

- ↑ a b c Bryman A. Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: how is it done?. Qualitative Research. 2006;6(1):97-113.

- ↑ Becher T. The significance of disciplinary differences. Studies in Higher Education. 1994;19(2):151-161.

- ↑ Brew A. Disciplinary and interdisciplinary affiliations of experienced researchers. Higher Education. 2007;56(4):423-438.

- ↑ Stirling A. Disciplinary dilemma: working across research silos is harder than it looks. [Internet]. The Guardian; 2014 [cited 2018 Nov 26]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/science/political-science/2014/jun/11/science-policy-research-silos-interdisciplinarity

- ↑ Jacobs JA. The Critique of Disciplinary Silos. In defense of disciplines: Interdisciplinarity and Specialization in the Research University. 1st ed. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press; 2014. p.13-26.

Disciplinary Categories and Their Effect On Gender Perception

This article will analyse the categorisation of gender through various disciplines. Exhibiting the relevant issues in each case suggest that the use of interdisciplinarity could help us arrive at more holistic inferences on such a controversial subject.

Disciplinary Categories

[edit | edit source]Disciplinary categories are results of breaking down academia into its constituent subject topics, termed disciplines, based on their content and research methods. These disciplines are then assigned to broad categories like humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. They are devised to organise various fields of knowledge, resulting in many institutions sharing the same system of classification. Consequently, they appear universal and absolute. However, dissent arises not only on the labels of categories, but also their non-mutually exclusive content. For instance, Economics can be a social science or an empirical science depending on the use of a qualitative or quantitative approach[1]. Fluctuations in disciplinary categories have also been witnessed over time and in different geographical locations, such as the creation of gender studies, initially women’s studies, as a new discipline in the 20th century West[2].

Similar issues of categorisation occur in human identification under the lenses of gender and sexuality.

Categorising Humans

[edit | edit source]Upon first interaction with a person, it takes only 600ms to recognise their sex[3]. The human brain immediately begins categorising the person based on factors like sex, race, and age[4]. However, studies increasingly reveal the ambiguity of boundaries between the elements of these categories[5]. French sociologist Christine Delphy observes that most work on gender presupposes that ‘sex precedes gender’[6]; sex being a biological function and gender a cultural identifier to separate traditional masculinity and femininity. However, an incoherence arises upon viewing the issue from different disciplines, indicating that the categorisation is not as universal as it appears.

Perception of Gender in Different Disciplines

[edit | edit source]Biology

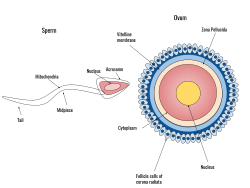

[edit | edit source]Biology denotes the difference in sex as the distribution of XX and XY chromosomes, the possession of either male or female genitalia, and the balance of hormones in our body. Testosterone is associated with stereotyped masculinity because it increases competitiveness and aggression whereas oestrogen is associated with feminine characteristics of increased emotion[7]. This forms the basis for cultural perceptions of males being better suited to hard labour and females to childbearing and domesticity[8]. This approach is largely criticised for being too deterministic in its analysis of gender and/or sex categorisation. Studies have shown that children classify others from their clothes more easily than from their sexual organs[9] demonstrating the reliance humans place on gendered archetypes when identifying others[10]. Hence, this biological classification provides solid grounds for the empirical study of gender and sexuality but is rendered fallible in consideration of the nature vs. nurture debate by lacking individualism.

Economics and Politics

[edit | edit source]Historically, capitalism has typically enforced a division of jobs deemed 'masculine' and 'feminine'. Jobs seen as useful for creating revenue and furthering society are considered superior, therefore assigned to men, and paid[11], whilst women are expected to perform unpaid domestic tasks[12]. For example in the 1950s nuclear family concept, men were given high-standing jobs whilst women were left as housewives or under-paid secretaries. Second-wave feminism helped to reduce these differences, thus encouraging women to fully enter the workforce.

The economy further enforces this division on a daily basis through mass-media and advertising, supposedly appealing to the artificial stereotypes associated with each gender, like women's beauty products. Whilst this is in attempt to maximise profits through appealing to a specific audience[13], the capitalist approach in this sense is argued to hinder approaches to gender equality by inadvertently prescribing gender stereotypes in widespread media.

Law

[edit | edit source]Many countries have started implementing laws regarding gender allowing citizens freedom of identity regardless of their biological sex. In 2016, Norway permitted anyone to legally change their sex without surgery[14] and Canada made denying gender theory illegal[15]. The UK also adopted the Gender Recognition Act. Nonetheless, most countries still do not accept non-binary gender.

Both extremes of legal gender recognition create conflicts in society. Countries not accepting of a third gender, gender reassignment surgeries, or name changes have been attacked by the left wing for their intolerance. Contrastingly, legalising gender changes before surgery is viewed as a security threat towards women due to possible abuse of the system. This occurred in Norway in 2016, when a woman felt uncomfortable when a biological male, legally identifying as female, entered the female bathroom of a gym. The woman talked to the staff about feeling unsafe, and ended up being sued for harassment. The court later ruled against any such claims[16][17].

As laws tend to dictate a public paradigm of right vs. wrong, the implementation of legal rulings regarding gender has dramatically helped the normalisation of non-binary gender. Yet, legal proceedings on such a divided issue have simultaneously given rise to further conflicts regarding expansion or retraction of these laws.

Linguistics

[edit | edit source]

In the West, it is common practice to indicate an individual's autonomous identity with the favoured pronoun he, she, they, or ze. A topic receiving much controversy is the use of pronouns as enforcing a binary of male and female. To incorrectly identify someone’s gender is construed as offensive. Hence, the use of additional pronouns introduces acceptance into a language. Whilst it may be positive to expand the lexical field of gender, each pronoun carries assumptions of gender norms. Just as ‘he’ implies masculinity, gender neutral pronouns can inadvertently cause associations with LGBTQ+ stereotypes[18].

This problem is expanded in gendered languages where it is necessary to express gender in many aspects such as adjectival agreement in French or the existence of gendered first-person pronouns in Japanese[19]. Such a range of identifiers can be problematic and cause further discrimination but are crucial for cultural expression. Oppressive regimes often prohibit gender descriptors differing from the traditional heterosexual male and female roles. Therefore, some people only discover their identity upon encountering a word to describe it; for example Jang Yeong-Jin only realised his homosexuality upon leaving North Korea[20]. This demonstrates that linguistics allow for both further expression and stereotyping of gender, inviting debate upon whether it is advantageous to have such a range of identifiers.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]The aforementioned disciplines are a small part of a greater discussion, but they suffice to illustrate the conflicting nature of gender categories. While natural sciences focus on sex and physical features, social sciences discuss the cultural norms attached to gender. Moreover, these terms are often used interchangeably, defined differently by almost all individuals. However conflicting, we still need these categories to follow our innate need to classify and better perceive the world and to accept and recognise the third gender.

Still, we must remember that any definitions are in no way absolute. Any broad topic must be broken down for thorough study, but it is imperative to keep in mind that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts, both in academia and gender and sexuality. Thus, one should utilise interdisciplinarity and systems thinking, exploring every related discipline, to arrive at solutions that better reflect reality. We must remember the interconnected cause and effect relationship amongst all the elements and the consequences of oversimplifying any processes involved.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Chetty R. Yes, Economics Is a Science. The New York Times. 2013 Oct 20. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/21/opinion/yes-economics-is-a-science.html

- ↑ Kaplan G, Bottomely G, Rogers L. Ardent warrior for women's rights. The Sydney Morning Herald. 2003 Jul 31. Available from: https://www.smh.com.au/national/ardent-warrior-for-womens-rights-20030731-gdh6tb.html

- ↑ Bruce V, Burton A, Hanna E, Healey P, Mason O, Coombes A et al. Sex Discrimination: How Do We Tell the Difference between Male and Female Faces?. Perception. 1993;22(2):131-152.

- ↑ Baudouin J, Tiberghien G. Gender is a dimension of face recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2002;28(2):362-365.

- ↑ Richards C, Bouman W, Seal L, Barker M, Nieder T, T’Sjoen G. Non-binary or genderqueer genders. International Review of Psychiatry. 2016;28(1):95-102.

- ↑ Delphy C. Rethinking sex and gender. Women's Studies International Forum. 1993;16(1):1-9.

- ↑ DeCecco J, Elia J. A Critique and Synthesis of Biological Essentialism and Social Constructionist Views of Sexuality and Gender. Journal of Homosexuality. 1993;24(3-4):1-26.

- ↑ Geary D. Male, female: The evolution of human sex differences. American Psychological Association; 1998.

- ↑ Case M. Disaggregating Gender from Sex and Sexual Orientation: The Effeminate Man in the Law and Feminist Jurisprudence. The Yale Law Journal. 1995;105(1):1-5.

- ↑ Kessler S, McKenna W. Gender: An Ethnomethodological Approach. University of Chicago Press; 2001.

- ↑ Federici S. Caliban and the Witch: Women, The Body, and Primitive Accumulation. Brookyln, NY. Autnomedia. 2004

- ↑ Women shoulder the responsibility of 'unpaid work' - Office for National Statistics [Internet]. Office for National Statistics. 2016 Nov 10. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/articles/womenshouldertheresponsibilityofunpaidwork/2016-11-10

- ↑ Mager J. and Helgesson J. Fifty Years of Advertising Images: Some Changing Perspectives on Role Portrayals Along with Enduring Consistencies, Sex Roles, 2011,64:238–252

- ↑ Norwegian law amending the legal gender. Transgender Europe. 2016. Available from: https://tgeu.org/norwegian-law-amending-the-legal-gender/

- ↑ Gender Identity and Gender Expression. Department of Justice Canada. 2017. Available from: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/pl/identity-identite/index.html

- ↑ Norway: A woman is accused of harassment for questioning a man who uses the women's changing room at a fitness centre. This is the translation of the case review. [Internet]. Womenwhosayno.blogspot.com. 2018. Available from: https://womenwhosayno.blogspot.com/2018/10/norway-woman-is-accused-of-harassment.html

- ↑ Danielsen I, Øygarden G, Aschehoug T. Sak 68/2018 [Internet]. Diskrimineringsnemnda; 2018. Available from: http://www.diskrimineringsnemnda.no/media/2218/68-2018-uttalelse-anonymisert.pdf

- ↑ Dembroff R, Wodak D. He/She/They/Ze. Ergo: An Open Access Journal of Philosophy. 2018;5(14):371-403. Available from: http://ergo.12405314.0005.014

- ↑ McConnell‐Ginet S. “What's in a Name?” Social Labeling and Gender Practices. The Handbook of Language and Gender. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2003. 69-97. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470756942.ch3

- ↑ Kim J, Kim S. North Korea's only openly gay defector: 'it's a weird life'. The Guardian. 2016 Feb 18. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/feb/18/north-koreas-only-openly-gay-defector-its-a-weird-life

Evidence in Nutrition

Nutrition sciences is a relatively young discipline.[1] There is much debate about what is healthy and which metric is best for measuring health. When we consider the structures around weight and dieting, studying human health has as many social implications as it does scientific. In this chapter, we take an interdisciplinary approach to addressing issues of evidence in relation to nutrition, dieting, obesity and health. To best understand not only evidence itself, but also the way people engage with it, we include nutrition science, marketing and economics in our discussion of these issues.

Research in Nutrition Science

[edit | edit source]Modern nutrition science began in the early 20th century with the supplementation of food with vitamins, which led to a decrease in deficiency related diseases. In wealthy countries, the discipline then became focused on dietary fat and sugar as posing health risks. In 1977 the US Senate Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs published a somewhat controversial report titled Dietary Goals for the United States that recommended a low fat diet. The evidence used in this report was called into question and found insufficient by the US National Academy of Sciences, Food and Nutrition Board.[1]

Methodologies

[edit | edit source]Data in nutrition sciences are gathered in many ways, ranging from ecological case studies, to intervention experiments. The methodology used to address deficiency diseases, which involved isolating a nutrient, was applied to research on the impacts of sugar and fat in the 1950s-70s. However, these methods, while effective for their original purpose, were not well suited to non-communicable diseases like obesity. Researchers today still use a lot of the same methods, but hold their data to a much higher standard of accuracy. Additionally, more recent publications are less likely to make far reaching claims about the relative health of different foods.[1]

Funding and Biases

[edit | edit source]The rise of the internet has given the general population access to a wide variety of studies, articles and arguments regarding health; however, the evidence presented in these sources may not always be legitimate. This applies even to studies that appear to be academic, when we consider research sponsorship. There have been multiple cases in which the outcome of a study has favoured the interests of the funding body.[2] For example, the Coca-Cola Company conducted research to show that exercise is more important to ones health than nutrition.[3]

Media outlets, such as the Guardian and Inside Philanthropy, have drawn attention to the issue of corporate influence in academic research. It has also garnered attention from academics, such as Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian of Tufts University, who recently published this study on conflict of interest in nutrition research. He concludes that “evidence for substantial bias has been identified in conclusions of industry- sponsored systematic reviews regarding the health effects of sugar-sweetened beverages and artificial sweeteners.”[4]

The presence of food industry capital in research is enormous, and is closely linked to the industry’s presence in national health groups in countries like the USA.[5] These findings call into question the validity of the evidence for health and nutrition.

Health

[edit | edit source]The official definition of health, given by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1948, states that "health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease of infirmity." [6] WHO fails to indicate how the subject is produced or measured.[7] Similarly, the OED and the NHSprovide scarce explanations of health. An article from the British Journal of General Practice defines ‘health’ as the capacity to make an adaptation to an environment, and is subject to a variety of forces that can change and damage us.[7] There is not only conflict over how to define health, but how to achieve that state. There is a large body of research and evidence, leading to few concrete conclusions.

Obesity and Related Diseases

[edit | edit source]There is extensive scientific research that suggests obesity is linked to problems with health, including cardiovascular diseases and Type II diabetes.[8] [9] The evidence regarding these findings is rather uncontroversial and accepted by both the scientific community and general population. Issues of evidence become more important in defining obesity. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “Overweight and obesity are defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that may impair health.” [6] There are multiple metrics used to measure obesity, including Body Mass Index (BMI) and percent body fat.

As stated in the introduction, evidence in nutrition is not just a scientific issue. It is also something we engage with on a social level. Society places high value on thinness, which impacts the general perception of health. If someone appears thin or "in shape" this is often taken as evidence of their good health. However, even people with normal BMIs can have what professionals call "normal weight obesity," which is also correlated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and other health problems.[10]

Advertising

[edit | edit source]Cambridge Dictionary defines advertising as “the business of trying to persuade consumers to buy given goods or services.” [11] In order to achieve this end, advertisers must provide reasons, or evidence, to support their product. The main issue in diet advertising is the manipulation of data or inaccurate paraphrasing of scientific findings. So called “soft” health claims, such as “makes you healthy” are intentionally vague, resulting in their interpretation as valid health claims.[12] According to M. Katan, ¨the formulation of soft claims [is] a fine art, creating claims that imply health effects without actually naming a disease.¨ [13] The issue of evidence in diet advertising in important not only because of the link between diet and health, but also because advertising is a dominant tool in shaping health preferences and knowledge about food. This especially impacts children and teenagers, as they are the most vulnerable to external influence.[12]

Some evidence suggests that food marketing practices may have led to positive public health outcomes, by changing dietary habits among American customers.[14] [15][16] For instance, there has been a trend away from high-fat foods since the 1970s.[15] Additionally, a report from the American Marketing Association argues that health claims in advertising can transform markets.[17] Allowing truthful claims by manufacturers may benefit consumers, as it increases the competitive pressures on companies to market the nutritional features of foods.[15] Health claims can also be considered a legitimate educational tool.[12]

On the other hand, many argue that health claims in advertisements are “designed to deceive,” by withholding some scientific evidence.[18] One study found that most advertisements promote “energy-dense, nutrient-poor” food, which has a questionable health benefit.[19] There is also a link between the proliferation of health claims, and the change of nutritional public policy. These claims are commonly found on food products throughout the world, but their regulation varies widely among countries. A recent WHO survey reported that among 74 countries, 35 have no regulation on health claims.[20]

Evidence is important in making and defending arguments about the value of health claims, yet it does not definitively support either side of the debate. This subjective and inconclusive nature of evidence has impacts on our health, policy and society as a whole.

Resources

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c Mozaffarian D, Rosenberg I, Uauy R. History of modern nutrition science—implications for current research, dietary guidelines, and food policy. BMJ [Internet]. 2018;:361-392. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/361/bmj.k2392

- ↑ Moodie A. Before you read another health study, check who's funding the research [Internet]. The Guardian. 2016 [cited 7 December 2018]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/dec/12/studies-health-nutrition-sugar-coca-cola-marion-nestle

- ↑ O’Connor A. Coca-Cola Funds Scientists Who Shift Blame for Obesity Away From Bad Diets [Internet]. New York Times Blog. 2015 [cited 7 December 2018]. Available from: https://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/08/09/coca-cola-funds-scientists-who-shift-blame-for-obesity-away-from-bad-diets/?_r=0

- ↑ Mozaffarian D. Conflict of Interest and the Role of the Food Industry in Nutrition Research. JAMA [Internet]. 2017 [cited 6 December 2018];317(17):1755-1756. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2623631

- ↑ Aaron D, Siegel M. Sponsorship of National Health Organizations by Two Major Soda Companies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine [Internet]. 2017 [cited 7 December 2018];52(1):20-30. Available from: https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(16)30331-2/fulltext?rss=yes#s0015

- ↑ a b Constitution of the World Health Organization. Bulletin of the World Health Organization [Internet]. 1946 [cited 6 December 2018];Basic Documents(45th Edition, Oct 2006):1. Available from: https://www.who.int/about/mission/en/

- ↑ a b Tulloch A. What do we mean by health? British Journal of General Practice [Internet]. 2005 [cited 2018Dec3];55(513):320–3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1463144/

- ↑ Golay A, Ybarra J. Link between obesity and type 2 diabetes. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism [Internet]. 2005;19(4):649-663. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16311223

- ↑ Burke G, Bertoni A, Shea S, Tracy R, Watson K, Blumenthal R et al. The Impact of Obesity on Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors and Subclinical Vascular Disease. Archives of Internal Medicine [Internet]. 2008;168(9):928. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2931579/

- ↑ Palmer S. When Thin Is Fat — If Not Managed, Normal Weight Obesity Can Cause Health Issues. Today’s Dietitian Vol 13 [Internet]. 2011 [cited 6 December 2018];(1):14. Available from: https://www.todaysdietitian.com/newarchives/011211p14.shtml

- ↑ Definition of “advertising” from the Cambridge Academic Content Dictionary © Cambridge University Press. Available from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/advertising

- ↑ a b c Williams, P. (2005). Consumer Understanding and Use of Health Claims for Foods. Nutrition Reviews, 63(7), pp.256-264.

- ↑ Katan, M. (2004). Health claims for functional foods. BMJ, 328(7433), pp.180-181.

- ↑ Daily dietary fat and total food-energy intakes--NHANES III, Phase 1, 1988–91. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association [Internet]. 1994;271(17):1309-1309. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8309459

- ↑ a b c Mathios A, Ippolito P. Food companies spread nutrition information through advertising and labels. Food Review. 1998;21:38-44.

- ↑ Stephen A, Wald N. Trends in individual consumption of dietary fat in the United States, 1920–1984. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1990;52(3):457-469.

- ↑ Calfee J, Pappalardo J. Public Policy Issues in Health Claims for Foods. Journal Of Public Policy and Marketing. 1991;10(1):33-53.

- ↑ Liebman B. Designed to Deceive. Nutrition Action Healthletter. 1999;(26):8.

- ↑ Lohmann J, Kant A. Effect of the Food Guide Pyramid on Food Advertising. Journal of Nutrition Education. 1998;30(1):23-28.

- ↑ Parker B. Food For Health – The Use Of Nutrient Content, Health, and Structure/function Claims In Food Advertisements. Journal of Advertising. 2003;32(3):47-55.

Evidence in the Gender Pay Gap

This chapter investigates the use of evidence within the Gender Pay Gap, both from a historical perspective, so as to establish this as an ongoing predicament, and from disciplinary lenses, highlighting current differences of opinion.

Historical Perspective

[edit | edit source]The Gender Pay Gap is a "measure of the difference between men’s and women’s average earnings".[1] It is commonly accepted that this disparity is not necessarily born from unequal pay for equal work but instead from a historically persisting custom of women's working restrictions, upholding cultural values, and labour division, with male careers often commanding higher wages.[2]

In 1906, twelve countries committed to a treaty[3] as part of a string of new laws dramatically limiting women's nighttime working-hours. To justify these laws courts often referred to "empirical evidence", originating from practical data collected from factory inspectors' reports and the observations of "medical men",[4] showing that night work cause negative physiological effects in women including loss of appetite, increasing morbidity and mortality.[5] Although the courts valued their evidence, we could question its validity based on whom it was collected by and how few people had access to this data.

In 1932, the BBC introduced a marriage bar[6] (the practice of terminating women's employment upon marriage or pregnancy, or not hiring married women[7]). Such restrictions were widespread during the interwar-years, and were even pursued in the public sector (within teaching, civil service and medicine[8]). It was argued that the bar was necessary in response to the economic depression and high male unemployment.[7] However, many felt that the economic rationale cited as evidence for the need of the bar was simply the publicly-presented evidence, and not the true reason why it was put into place. Commentators believed that a social consensus on women's participation in public life was instead to blame.[9] Here, we are faced with how evidence might be selected and manipulated to support one's own rationale.

These are just two of many historical examples of the ongoing issues related to evidence within the restriction of women's work.

Over time, the ways we collect and use evidence have dramatically evolved. This has allowed disciplines already addressing the issue (such as Economics) to delve further into the situation, as well as allowing a plethora of disciplines to approach the issue (such as Sociology and Psychology).

Current disciplinary perspectives

[edit | edit source]Economics uses quantitative evidence concerning disparities in wages and working hours between sexes to explain the gender pay gap. Their main focus is decomposing this evidence into particular gendered categories concerning age, field of study, level of education, interests and balance between home and work. By doing so, the proportion of this pay gap caused by gender discrimination decreases.

Indeed economists consider that data generalisations and lack of analysis of all relevant variables have caused the contradictions surrounding this gap.[10] [11] For instance, its political/social discourse mostly uses imprecise evidence such as: “women’s wages”, whilst economic studies focus on highly specific data like “Hours distributions and hourly wage penalties and advantages for hourly workers across six occupational groupings, by sex”.[12]

The decomposed evidence used, such as studies of trends in variables and convergence analysis, have concluded that a majority of this pay gap can be explained by the difference in choices men and women make. For instance, economists (such as Harvard professor Claudia Goldin) support the use of Becker’s human capital theory to explain why women orient themselves towards the jobs they do.[13][14]

Sociology focuses on the reasons underpinning the degree of occupational sex segregation and why the sexual division of labour is significant in the difference in remuneration for both sexes. Whilst sociologists recognise that Becker's human capital theory plays a certain role in gender wage disparity, they argue that it in reality it only accounts for a fraction of the rift.[15] Rather than focusing on the autonomic "supply" side decisions, sociologists highlight broader cultural and infrastructural mechanisms as key contributors to the issue.[16]

To explain sexual division of labour, sociology focuses on gender socialization as a cause of sex segregation. Their evidence for this are sociological studies displaying a positive correlation between a society's emphasis on gender differences and the extent of sex segregation.[17] On a structural level, sociologists such as Reskin highlight personnel practices actively discouraging the mobility of sexes between certain occupations, particularly in the form of work-time schedules and work equipment.[17]

Sociology suggests sexual division of labour in the workforce is paramount as female dominated spheres of work earn less on average – not because they are able to offer less in terms of human capital but because typically female work is systematically and culturally undervalued.[18] [17] As a result, policies that ban direct discrimination fail to address the broader issue.

Psychology focuses on the sundry and specific behaviour of individuals, unlike sociological theory. They are interested in the wage-related impacts of confidence and individual’s personality as related to the skills of risk-taking, negotiation and competitive behaviours.[19]

Psychology uses evidence collected from psychometric instruments, including achievement motivation and personality trait scales, capturing confidence. This approach largely ignores the wider social forces that may explain the gender pay gap.

Over-confidence is also statistically modelled so as to produce quantitative evidence for the variables giving rise to pay differences. An example of this would be the Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition model that suggests we can investigate dissimilarities in gender characteristics to explain differences in their remuneration for said characteristics.[20]

Evaluating Evidence

[edit | edit source]We could argue that it was the lack of access to and manipulation of evidence that allowed for women's working restrictions to be sanctioned. Nowadays, however, we appear to be facing a different problem. Despite an abundance of accessible evidence, researchers today primarily interpret evidence from their own disciplinary perspective, often leading to a clash of opinions as explored above.

Economics often disregards qualitative or theoretical evidence, favouring quantitative empirical evidence. Whilst sociology values quantitative evidence, it recognises that it cannot sufficiently reflect the socio-cultural forces at hand and as a result gives equal precedence to qualitative evidence.[17][21] Furthermore, evidence used in psychology is individualistic, unlike the societal models of sociology, resulting in diverging conclusions regarding the pay gap.

Clearly, single-disciplined researchers tend to collect evidence from their own disciplinary perspective to inform their conclusions, lacking an understanding of that of other disciplines. Therefore, we believe in the need for interdisciplinary thinkers to overcome the lack of cohesion within the disciplinary perspectives. Due to their interdisciplinary foundations, an interdisciplinary researcher would have the capacity to approach and understand the theories provided by different disciplines without the ulterior motive to proliferate their own discipline's agenda. We feel an interdisciplinary approach would allow for a holistic interpretation of the breadth and depth of the evidence now available to us, hence reaching a more universal consensus.

Bibliography

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Equality and Human Rights Commission. What is the difference between the gender pay gap and equal pay?. [Internet] [Cited 8 August 2018, Accessed 6 December 2018]. Available at: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/advice-and-guidance/what-difference-between-gender-pay-gap-and-equal-pay

- ↑ Griffin, Emma. What’s to blame for the gender pay gap? The housework myth. [Internet] The Guardian. 12 March 2018. [Cited 7 December 2018] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/mar/12/history-blame-gender-pay-gap-housework

- ↑ Treaty Series. No. 21. 1910. International Convention respecting the Prohibition of Night Work for Women in Industrial Employment. Signed at Berne, 26th September, 1906 (Treaties, Conventions, &c: Women (Night Work)). 20th Century House of Commons Sessional Papers. Command Papers, Cd. 5221, CXII.275. [Cited 1 December 2018] Available at: https://parlipapers.proquest.com/parlipapers/docview/t70.d75.1910-012481

- ↑ Goldmark, Josephine. Fatigue and Efficiency – A Study in Industry. New York: Charities Publication Committee; 1912. Page 252.

- ↑ Goldmark, Josephine. Fatigue and Efficiency – A Study in Industry. New York: Charities Publication Committee; 1912. Page 211. As referenced in: Woloch, Nancy. A Class by Herself: Protective Laws for Women Workers, 1890s–1990s. Princeton University Press; 2015. Page 93.

- ↑ Murphy, Kate. A marriage bar of convenience? The BBC and married women's work 1923–39. Twentieth Century British History. 2014; Volume 25 Issue 4. Pages 533-61. [Cited 2 December 2018] Available at: https://academic.oup.com/tcbh/article/25/4/533/1638235?searchresult=1

- ↑ a b Sisterhood and After Research Team. Marriage and civil partnership. [Internet] Sisterhood and After, The British Library; March 2013. [Cited 2 December 2018] Available at: https://www.bl.uk/sisterhood/articles/marriage-and-civil-partnership

- ↑ Sturge, Mary. THE MARRIAGE BAR. The Lancet. 8 October 1921: Volume 198, Issue 5119, Page 779. [Cited 3 December 2018] Available at: https://ac.els-cdn.com/S0140673601227482/1-s2.0-S0140673601227482-main.pdf?_tid=c7423ef6-12f1-40b8-8608-b342e4fba8ca&acdnat=1543758896_3bca71289b6f8e09d7d7df7e085197c9

- ↑ Redmond, Jennifer and Harford, Judith. “One man one job”: the marriage ban and the employment of women teachers in Irish primary schools. Paedagogica Historica. 2010: Volume 46, Issue 5, Pages 639-654. [Cited 2 December 2018] Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/00309231003594271

- ↑ The Economist. Are women paid less than men for the same work? [Internet] The Economist Newspaper; 2017 [Cited December 9 2018]. Available at: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2017/08/01/are-women-paid-less-than-men-for-the-same-work

- ↑ Kai, Lui. Explaining the gender wage gap: Estimates from a dynamic model of job changes and hours changes. Faculty of Economics, University of Cambridge, Department of Economics, Norwegian School of Economics, and IZA. [Internet] 2016. Pages 411-412. [Cited 8 Dec 2018] Available at: http://ftp.iza.org/dp9255.pdf

- ↑ Goldin C. Hours flexibility and the gender pay gap. Center for American Progress; April 2015. Pages 13-15.

- ↑ Goldin, C. Human Capital. In: Handbook of Cliometrics. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Verlag; 16 March 2016.

- ↑ Tverdostup M. and Paas T. GENDER UNIQUE HUMAN CAPITAL AND LABOUR MARKET RETURNS. University of Tartu, School of Economics and Business Administration, Estonia. [Internet] 2017. Available at: file:///Users/isabelle/Downloads/25_Tverdostup_Paas%20(2).pdf

- ↑ England P. The Failure of Human Capital Theory to Explain Occupational Sex Segregation. The Journal of Human Resources [Internet]. 1982; 17(3):358. [Cited 1 December 2018] Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/145585?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- ↑ 5. Andersen J. The Gender Wage Gap: Exploring the Explanations. [Internet]. 2018. [Cited 1 December 2018] Available at: http://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2097/760/JaimeAndersen2008.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- ↑ a b c d Reskin B, Bielby D. A Sociological Perspective on Gender and Career Outcomes. Journal of Economic Perspectives. [Internet] 2005;19(1):71-86. [Cited 2 December 2018] Available at: https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdf/10.1257/0895330053148010

- ↑ England P. Gender Inequality in Labor Markets: The Role of Motherhood and Segregation. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society [Internet]. 2005; 12(2):264-288. [Cited 6 December 2018] Available at: https://academic.oup.com/sp/article/12/2/264/1685513

- ↑ Frédéric Palomino, Eloïc-Anil Peyrache. Psychological bias and gender wage gap. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization; Volume 76, Issue 3, 2010, Pages 563-573.

- ↑ Leonora Risse, Lisa Farrell, Tim R L Fry. Personality and pay: do gender gaps in confidence explain gender gaps in wages? Oxford Economic Papers; Volume 70, Issue 4, 1 October 2018, Pages 919–949.

- ↑ Lips, H. The Gender Pay Gap: Challenging the Rationalizations. Perceived Equity, Discrimination, and the Limits of Human Capital Models. Sex Roles. 2012; 68(3-4):169-185.

Reliability of Legal Evidence

This chapter will explore the benefits and drawbacks of two types of legal evidence, eyewitness testimony and DNA, with reference to the disciplines of psychology and forensic science. It will evaluate the reliability of these two types of evidence, by examining their values and implications in the world of law.

Reliability in the Context of Different Disciplines

[edit | edit source]In law, reliability of evidence is the degree to which the examiner is able to rely upon it in coming to a decision.[1] However, its scope and limitations are directly influenced by what discipline the evidence stems from. In psychology, reliability is assessed through the level of consistency of research findings [2]. Eyewitness testimony places 100% reliance on the human memory, which may be tainted by several psychological influences [3], lowering its reliability. Alternatively, forensic science in law is highly authoritative and relied upon due to its validity and accuracy which has made DNA evidence increasingly unassailable [4], yet problems of reliability still exist due to its circumstantial and subjective nature.

Eyewitness Testimony as Legal Evidence

[edit | edit source]Eyewitness testimony in legal terms refers to an account provided by people who have witnessed first-hand the event under trial [5]. In a large share of criminal cases where reliable evidence may be scarce, courts often turn to eyewitness statements to secure their final conviction. Despite it being the main form of evidence in many cases [6], reports indicate that they can be severely inaccurate and are responsible for over 70% of the world's documented false convictions [7], resulting in an inherent trade-off between relevance and reliability.

Psychology of Eyewitness Testimony

[edit | edit source]The reliability of eyewitness testimony can be skewed by a variety of psychological factors; even everyday bodily influences such as anxiety/stress, memory decay and poor eyesight have been shown to influence false testimony [6]. Through research, psychologists have concluded that eyewitness evidence can be contaminated by an individual’s visual perception and may lead to incorrect reconstructions of the crime [8]. An often heavier influence to false testimony is “eyewitness talk”, whereby witnesses discuss their recollection of events among themselves and subsequently alter their own memory based on the evidence of their fellow witnesses [6], resulting in their inability to differentiate between their own memory and information learned after the incident [7]. An individual's memory reconstruction may also be inherently biased by their specific cultural background and values [9]. These psychological factors depict how heavily succumbed the human mind is to internal and external influences, no matter how confident the eyewitness may be, and the resulting unreliability of eyewitness testimony in legal trials, despite its prevalence in today’s legal system.

DNA as Legal Evidence

[edit | edit source]Legal Benefits of DNA Forensics

[edit | edit source]

DNA profiling has been considered the biggest breakthrough in forensic sciences since the discovery of fingerprinting. Since the 1986 Pitchfork case, the use of DNA in the domain of forensic science has seen itself multiply exponentially. Alec Jeffreys, University of Leicester geneticist, used DNA to convict the double murderer and rapist, Colin Pitchfork, which cleared the name of the innocent suspect, Richard Buckland, making it the first legal case solved by DNA [10]. It is important to note that in this case, DNA was not used as evidence but rather helped the authorities pinpoint a suspect. The results observed and the range of use of DNA technology was applauded by many, popularizing its use in forensic labs worldwide[11].

The late 90's saw fast development in the use of DNA, leading to a normalization of its use in court. However, due to the margin for human error and skepticism, this method was not automatically adopted as the standard in court. This aversion to using DNA led to the creation of operations such as the Innocence Project (USA), whose goal was to use DNA testing positively in order to clear the name of those wrongfully accused. To date, it has helped 326 people in the 70% of cases where wrongful conviction was made due to eyewitness misidentification[12]. According to the Innocence Project, tens of thousands of cases in the USA have benefitted from DNA sampling since 1989. DNA has also changed the face of forensic science to a greater extent, as violent crimes, such as rape and murder, are most often committed by multiple time offenders, leading to the creation of DNA databases which can then be used in future investigations[13].

Drawbacks of DNA Forensics

[edit | edit source]Mishandling of DNA Forensics

[edit | edit source]DNA forensics are highly perceived as an irrefutable and reliable piece of evidence, which can overturn a defendant's adjudication[14]. In fact, any biological evidence collected at crime scenes can be analysed through DNA testing[15]. Although, this practicability has led to faulty forensic analysis of DNA, which have caused many wrongful convictions. In 2013, the New York medical examiner's office reviewed more than 800 rape cases that may have involved crime investigators who were introduced to reports with mishandled DNA evidence[14]. Mishandling of DNA evidence may include the swapping of items within labs, cross-contamination, or the disregard for certain required lab protocols.

-American biologist and the founder of the Idaho Innocence Project, Greg Hampikian

Misinterpretation of DNA

[edit | edit source]The nature of DNA forensics, in which a sample can include a mix of many potential suspects, makes it very difficult for analysts to distinguish them. In fact, one person's DNA can be found from a place they have never even visited [16]. This is caused by secondary transfer whereby human skin cells shed and get carried to different places by other people[17]. In 2013, Michael Coble, an American geneticist of the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg, carried out a scenario test which asked 108 laboratories if a particular DNA sample was part of the mix of DNA found on a ski mask from a particular crime scene. 73 laboratories inaccurately concluded that the DNA sample was part of the mix found from the mask [4]. These results clearly indicate how DNA evidence is afflicted by the analysts' discretion. Forensic science is therefore, highly circumstantial, meaning that it is subject to interpretation and by itself, cannot be treated as equivalent to scientific truths[17].

Overall Implications

[edit | edit source]A research report[18], published by the National Research Council states that the true value of forensics lies in the quality of the biological evidence collected at crime scenes and not necessarily solely on its scientific applicability. Thus, the value of evidence is heavily dependent on expert interpretation, as it does not come from scientific data, but rather from conclusions drawn from several possibilities derived by forensic science. Furthermore, psychological contamination of eyewitness accounts must be considered as it can drastically impact its credibility. It is a necessary and worthwhile task to think about the possible flaws inherent in different kinds of evidence and question professional consensus when convictions must be made in life-altering legal cases. Thus, the onus is on scientific and legal professionals to recognize and interpret the true 'value' of all evidence and adopt a holistic approach to evidence evaluation when concluding a legal case.

References

[edit | edit source]

Evidence in Climate Change

Case study: Glaciers retreat in the Andes

[edit | edit source]Climate change has had many impacts on the outlines of our glaciers today, like in the Andes or in the Himalaya where ice land has been retreating over the last few decades.[19]

The Quelccaya Ice Cap (QIC) in the Andes, Perù, faces major changes in its amount of ice. Studies claim that minor changes in climate change are importantly linked to the changes in the ice cap's mass balance.[20] The landscape of the QIC dramatically changed since 1978 (Fig. 1):[19] qualitative evidence is here proof of the changes in geography. This retreat is due to an important rise of the Freezing Level Hight (FLH), which has approximately increased of 160 m the past six decades,[21] this increase due itself to global warming in the Andes [22] Quantitative evidence such as air temperature records on land (Ta) [23] can also support these variations. With the help of specific data methods,[21] experiments have measured Ta at the QIC summit. These studies have measured a Ta warming rate of 0.14 °C/decade over the periods 1979–2016 in the area.[21] These Ta anomalies have an influence on the FLH fluctuations of the QIC which triggers the loss of ice mass in the QIC. Global warming again has effects on the geographical frame of the Andes.[22]

Hence, as glaciers retreat, populations experience a shortfall in water supply. In response to that, more expenses have to be provided to reply to agricultural and living needs.[24] For instance, the Rio Orientales project in Perù is based on implanting a water tunnel and bring water from other further sources to reply to water needs in response to the glaciers retreat: these economic changes support the existence of climate change.

The example of glaciers retreat in the Andes illustrate that diverse types of evidence in different fields can support the existence of climate change.

Introduction to evidence

[edit | edit source]Evidence in geography

[edit | edit source]Because geography is the science that predominantly portrays our world through images, evidence holds a very delicate important role. Representing the spheric earth on a flat surface, thus creating a map is an ongoing challenge that begun centuries ago. Reading a map must be enlightened by reason and critical thinking because the map is also an effective instrument for creating representations which then evolve with history. For instance, the chosen projection alters the appearance of the map: distortions of distance, direction and scale, which question the importance of evidence in representing the world. Because there is so much evidence, thanks to satellites, and because maps are difficult to create, choices must be made. Indeed, the mapmaker may use different evidence than another maker as the map is the product of his choices. Two types of evidence exist in geography:[25] evidence from qualitative research and evidence from quantitative research. Qualitative evidence informs geography with the support of observations, opinions and unnumbered evidence. Quantitative evidence is informed by numbers, surveys and statistical information.

Evidence in Economics

[edit | edit source]In Economics – which can be seen as a counter-discipline to Geography –, the question of how reliable theories are, and whether the evidence that is used to establish these, is reliable, raises. Economics is described as either a social science or a natural science, however in the social sciences, evidence is often acquired through anecdotal evidence or testimonial evidence[26] which are rather subjective, hence the findings may be considered as less reliable by one. If economics is seen as a natural science, scientific evidence is being used to make assumptions. One issue that arises in economics is that often the evidence that exists does correspond with the theory behind it, per contra a further link between evidence and real life is difficult to establish.

Evidence in Climate Change

[edit | edit source]Cultural differences in the acquisition of evidence

[edit | edit source]In economics, different international viewpoints are considered and discussed when examining and evaluating the impacts of climate change – e.g. at the G20 summit where international political leaders debate about the impacts of climate change –, hence evidence can be interpreted and appraised differently across cultures; working together on the worldwide issue is essential. Cultural differences influencing evidence also appear in the natural sciences; one study carried out by Luncz,[27] investigating behaviour of Chimpanzees across cultures, emphasises the existence of varying evidence across cultures thus the various approaches towards elucidation of evidence. Referring this to the real world, cultural differences lead to differences in evidence, which suggest different approaches towards policy making in the scientific study of economics.

Economics of Climate Change

[edit | edit source]Climate Change reveals differing approaches to evidence from various disciplines. According to economists, climate change is an outcome of greenhouse-gas emissions leading to negative externalities of production hence creating costs that are not paid for by those who generate the emanations.[28] The Kyoto Protocol (1997), aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emission and[29] soon received feedback that it would harm economic growth. In 1997 Connaughton argues that the protocol would reduce output by up to $400billion in 2010, which is close to the calculations of the EIA from 2008 expecting a decrease in GDP by $397billion billion.[30] It appears that over a time period of 11 years, researchers were able to interpret data similarly; concluding the same. The scientific study of economics may therefore be considered as reliable hence truthful, as evidence shows that even when acquiring it at different times, the outcome is interchangeable.

Geography in climate change

[edit | edit source]Largely caused by humans in the burning of fossil fuels, climate change has many impacts on the outline of our world today, modifying our landscapes.[31] Because geography is a wide and resourceful discipline with sub-disciplines, its implication in the understanding of climate change is crucial. Geography indeed offers new understandings of the issue, varying from perceiving spatial dimensions of climate change to grasping the urban changes of global warming. Generating global warming, climate change covers transformations like rising seas and melting ice as well as extreme weather events which have consequences on the geographic world.[32] Climatology (itself classified within physical geography) addresses the issue through its focus on dynamic and statistical climatology.[33] Geography also aids in understanding the possible effects of climate change on environmental systems and societies. K. O’Brien and R. Leichenko suggest that there are winners and losers of climate change.[34] These winners and losers are divided regarding their geographical position: winners ‘will include the middle- and high- latitude regions, whereas losers will include marginal lands in Africa and countries with low-lying coastal zones’, hence showing how geography adds to the economic study of climate change and offers different perspectives.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Economics and geography work hand in hand in order to understand climate change. Geography, with its sub-disciplines, brings the basis of the scientific work in order to fully grasp the issue while economics focuses on its impacts and future and how it is apprehended by society. Various types of evidence used by both disciplines aid in the global understanding of climate change. Both disciplines are crucial in order to comprehend the issue and be able to live with it, and, to a certain extent fight it.

- ↑ Collins Dictionary of Law. W.J. Steward; 2006. Available from: https://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/reliability [Accessed 4th December 2018].

- ↑ McLeod, S. What is Reliability? Available from: https://www.simplypsychology.org/reliability.html [Accessed 7 December 2018]

- ↑ Jenkins, L. Memory in the Real World: How Reliable is Eyewitness Testimony? Available from: https://www.psychreg.org/reliable-eyewitness-testimony/ [Accessed 7th December 2018]

- ↑ a b c Starr D. Forensics gone wrong: When DNA snares the innocent Science | AAAS. 2016 [cited 1 December 2018]. Available from: http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/03/forensics-gone-wrong-when-dna-snares-innocent

- ↑ McLeod, S. Eyewitness Testimony. Available from: https://www.simplypsychology.org/eyewitness-testimony.html [Accessed 28th November 2018].

- ↑ a b c Mojtahedi, D. New research reveals how little we can trust eyewitnesses. Available from: https://theconversation.com/new-research-reveals-how-little-we-can-trust-eyewitnesses-67663 [Accessed 28th November 2018].

- ↑ a b Mojtahedi, D., Ioannou, M. & Hammond, L. The Reduction of False Convictions. The Custodial Review. 2017; 81: 12. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314082250_The_Reduction_of_False_Convictions [Accessed 28th November 2018].

- ↑ Stambor, Z. How reliable is eyewitness testimony? Monitor on Psychology. 2006; 37(4): 26. Available from: https://www.apa.org/monitor/apr06/eyewitness.aspx [Accessed 28th November 2018].

- ↑ UKEssays. Relevance and Reliability of Eyewitness Testimony in Court. Available from: https://www.ukessays.com/services/example-essays/criminology/relevance-and-reliability-of-eyewitness-testimony-in-court.php?vref=1. [Accessed 28th November 2018].

- ↑ Cobain. I. Killer Breakthrough - the day DNA evidence first nailed a murderer. The Guardian. 2016, Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/jun/07/killer-dna-evidence-genetic-profiling-criminal-investigation [Accessed 3rd December 2018]

- ↑ Parven. K. Forensic use of DNA information: human rights, privacy and other challenges. University of Wollongong Thesis Collections. 2012. Available from: https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.co.uk/&httpsredir=1&article=4695&context=theses] [Accessed 3rd December 2018]

- ↑ Innocence Project. DNA Exonerations in the United States. 2018. Available from: https://www.innocenceproject.org/dna-exonerations-in-the-united-states/ [Accessed 3rd December 2018]

- ↑ Parven. K. Forensic use of DNA information: human rights, privacy and other challenges. University of Wollongong Thesis Collections. 2012. Available from: https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.co.uk/&httpsredir=1&article=4695&context=theses] [Accessed 3rd December 2018]

- ↑ a b Goldstein J. New York Examines Over 800 Rape Cases for Possible Mishandling of Evidence. The New York Times. 2013, Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/11/nyregion/new-york-reviewing-over-800-rape-cases-for-possible-mishandling-of-dna-evidence.html [Accessed 1st December 2018]

- ↑ DNA Evidence: Basics of Identifying, Gathering and Transporting | National Institute of Justice. National Institute of Justice. 2012, Available from: https://nij.gov/topics/forensics/evidence/dna/basics/pages/identifying-to-transporting.aspx [Accessed 4th December 2018].

- ↑ Papantonio M. Faulty DNA Evidence Is Causing False Convictions - The Ring of Fire Network. The Ring of Fire Network. 2018, Available from: https://trofire.com/2018/05/30/faulty-dna-evidence-is-causing-false-convictions/ [Accessed 4th December 2018].

- ↑ a b Rohrig B. Open for Discussion: How Reliable Is Forensic Evidence? - American Chemical Society. American Chemical Society. 2016, Available from: https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/resources/highschool/chemmatters/past-issues/2016-2017/october-2016/forensic-evidence.html [Accessed 1st December 2018].

- ↑ Committee on Identifying the Needs of the Forensic Sciences Community, National Research Council (2009). Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward. Washington, D.C.: THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS. Available at: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/228091.pdf [Accessed 1 Dec. 2018].

- ↑ a b Thompson, L.G., Mosley-Thompson, E., Brecher, H., Davis, M., León, B., Don, L., Lin, P.-N., Mash- iotta, T., and Mountain, K., (2006), Abrupt tropical climate change: Past and present, National Academy of Sciences Proceedings, vol. 103, p. 10536– 10543, doi:10.1073/pnas.0603900103.

- ↑ Stroup J. S., Kelly M. A., Lowell T. V., Applegate P. J., Howley J. A. (2015), Late Holocene fluctuations of Qori Kalis outlet glacier, Quelccaya Ice Cap, Peruvian Andes, Geology v. 42, p. 347–350, doi:10.1130/G35245.1

- ↑ a b c Yarleque C., Vuille M., Hardy D. R., Timm O. E., De la Cruz J., Ramos H., Rabatel A., (2018), Projections of the future disappearance of the Quelccaya Ice Cap in the Central Andes Scientific Reports vol. 8, Article number: 15564, doi:10.1038/s41598-018-33698-z

- ↑ a b Bradley R. S., Keimig F. T., Diaz H. F.,Hardy D. R. (2009), Recent changes in freezing level heights in the Tropics with implications for the deglacierization of high mountain regions Geophysical research letters, vol. 36, L17701, doi:10.1029/2009GL037712

- ↑ Diaz, H. F., and N. E. Graham, 1996, Recent changes in tropical freezing heights and the role of sea surface temperature, Nature, vol. 383, 152–155, doi:10.1038/383152a0.

- ↑ Vergara, W., A. Deeb, A. Valencia, R. Bradley, B. Francou, A. Zarzar, A. Grünwaldt, and S. Haeussling (2007), Economic impacts of rapid glacier retreat in the Andes, Eos Trans. AGU, 88(25), 261–264, doi:10.1029/2007EO250001

- ↑ Roberts M., (2010) What is “evidence-based practice” in geography education?, International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, vol.19, article number: 2, pp. 91-95, doi: 10.1080/10382046.2010.482184

- ↑ Phil Howard, Types of Evidence, available from: https://medium.com/@pnhoward/types-of-evidence-in-social-research-d52e756df855, date of last access: 24th of October 2018

- ↑ Luncz L, Mundry R, Boesch C. Evidence for Cultural Differences between Neighboring Chimpanzee Communities. Lepizig; 2012 p. 1.

- ↑ Stern N. The Economics of Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press; 2007.

- ↑ Fletcher S. Global climate change: The Kyoto Protocol. Policy Papers; 2003 p. 1-4.

- ↑ Corbett J. Economics of Climate Change | Encyclopedia.com [Internet]. Encyclopedia.com. 2008 [cited 28 November 2018]. Available from: https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/energy-government-and-defense-magazines/economics-climate-change

- ↑ Earth Science Communications Team at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology (2018), What’s in a name? Weather, global warming and climate change, available at: https://climate.nasa.gov/resources/global-warming/

- ↑ European Commission (2018), Climate change consequences available at: https://ec.europa.eu/clima/change/consequences_en

- ↑ Aspinall R. Geographical Perspectives on Climate Change. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2010;100(4):715-718.

- ↑ O'Brien K, Leichenko R. Winners and Losers in the Context of Global Change. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2003;93(1):89-103

Evidence for the Implications of the Cow in Contemporary India

Introduction

[edit | edit source]

According to the 2011 census, 79.8% of Indians practice Hinduism, with only 6% practicing Buddhism, Jainism, and other faiths[1]. India's second largest religious population is Islam: 14.2% of Indians identified as Muslims, which equates to about 172 million people. Unlike Hindus and other observed religions in India, Muslims do not believe the cow to be sacred, meaning they continue to kill and eat the animal across the country. In the 2014 Indian election, the issue of the cow was more hotly debated than objectively more important problems such as corruption and women's safety.[2] In this chapter, we will address varying issues raised by the cow's status in India from within different disciplines.

Religious and Historical Background

[edit | edit source]A fundamental belief in Hinduism is that all living beings have souls and practicing non-violence to all creatures is the highest ethical value[3].

When the Indo-Aryan migration happened between 1900 BCE to 1400 BCE[4], cows were the primary domesticated animals and a necessary resource for the migrants, serving as both transport and food. The Indus Valley Civilizations started to gather in the Ganges River Basin where soil was fertile and weather was suitable for agriculture, causing the population to boom. Conflict began to break out as loss of forests and natural resources put a strain on the environment and lifestyles of communities. Upperclass citizens from Vedic continued to ignore the suffering of most of population, continuing to kill livestock to satisfy their own appetite. An Anti-Vedic trend challenged this sense of entitlement, opting to protect the welfare of cows and avoid killing them. This movement led to the genesis of Buddhism, the first non-violent religion in India. Despite their initial views, the upperclass from the Vedic readjusted their practices, choosing to protect the cow. This change in beliefs was the start of Hinduism. Similar ideas were also adopted by followers of the Jainist faith; as an ancient Indian religion, Jainism operates on the fundamental beliefs that violence against all living beings, including cattle, is wrong[5].

Varying views on cow veneration were crucial to the formation of India's major religions. Historically, the contrasting ideas put a strain on harmonious living, and this religious input continues to cause problems in the contemporary climate.

The Cow in Politics

[edit | edit source]India is a federal parliamentary democratic republic, with the Centre-Left Indian National Congress and Centre-Right Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) forming the two main parties. Currently, BJP, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is most largely represented both in national parliament and at the state level across the country.[6]

Historically, the cow has always been a polarising element of Indian politics. As early as 1870, Sikh sects in Punjab were organising cow protection movements, with the Hindu religious leader Dayananda Saraswati founding a cow protection committee a decade later in 1882.[7] Due to tension caused by contrasting religious views in India, conflicts over cow slaughter have provoked riots for over 120 years: in 1893, more than 100 people were murdered as a result of religious riots, with eight dying in 1966 following a demonstration outside parliament in Delhi when protesting a national ban on cow slaughter.[8] More recently, religious tension continues to cause problems, with cow vigilante violence targeting India’s Muslim population. Between 2010 and 2017, it was reported that there were 63 attacks[9] caused by tension relating to the sanctity of the cow in India.

This swelling has been attributed to the surge of Hindu Nationalism in India, influenced by the BJP’s election.[10] Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been vocal regarding his views on the importance of the cow, going as far as to promote using cow urine as a medicinal product.[11] In this way, he has encouraged many vigilante groups to continue fiercely protecting the cow, with many Hindu Nationalists claiming to feel “empowered” by Modi and his party.[12] After winning in 2014, the BJP has encouraged groups with strict laws concerning the cow: in Uttar Pradesh, India’s largest state, BJP chief officer Yogi Adityanath began his tenure by enforcing a strict lockdown on slaughterhouses.[9]

The political tension continues to evolve as the cow continues to be a huge campaign strategy for the BJP and Centre-Left Congress alike. The BJP are seeking to replace the tiger with a cow as the national animal of India.[13] Congress is also seeking to capitalise on cow welfare as their main campaigning tactic for drawing voters. In the state of Madhya Pradesh, Congress declared that each village within the state boundaries will have a cow shelter. In an attempt trump this, the BJP stated that cow ministry will be available to Madhya Pradesh residents.[14] It’s clear that the cow continues to be an incredibly vital yet polarising aspect of Indian politics.

The Cow in Industry

[edit | edit source]Fashion Industry

[edit | edit source]With India being a huge exporter of fashion goods for high street chains like Zara and fashion houses such as Armani alike, a 2017 crackdown on leather use proved a huge problem for many designers relying on Indian factories for their production. India is the world's second largest producer of footwear and leather garments, selling $13 billion worth of goods in the 2016 tax year.[15] The BJP ruled that using cows and buffalo for leather is strictly forbidden; the effects have proven devastating for factory workers across India, who face redundancy, as well as foreign companies. The leather industry is predominantly ran by India's Muslim population, and the clamp down has caused greater religious division and tension nationwide,[16] with Muslim workers risking their lives in illegal abattoirs to export leather and maintain small businesses.

Beef industry

[edit | edit source]In 2016–2017 165.4 million tonnes were created in India, the highest in the world. Additionally, India is predominantly dependent on bull power for agriculture and transportation. Hence the cow is seen as so valuable as it fulfils so many human needs in India, which leads to the second highest cattle population of 190 million.[17] However, this huge number of cattle causes societal unrest towards those who kill cows for meat that do not give any economic value anymore. Non-producing dairy cows and infertile cows get sold and end up in the slaughterhouses. Additionally, it is well known that any ban on slaughterhouses or the discontinuation of this industry would affect Muslims and Dalits the most, as these poorest mostly work in this industry. It would also create illegal slaughterhouses and unsafe labour environments, creating an even bigger wealth disparity. Even now, people that had anything to do with this industry are still murdered, beating up and publicly hung.[18] The Indian government wants to maintain its income and export on cow industries, yet not dressing the social and religious implications.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Given that the economic market is so big on using the parts of the cow, but also the political and religious unrest surrounding this topic, it is valuable to look at this issue from an interdisciplinary perspective. The ideal solution could be found by reusing non-producing cows in other manner such as fertilizing dung[19] and avoiding the slaughterhouse, decreasing the societal unrest.

References

[edit | edit source]Evidence in driverless cars