Managing Groups and Teams/Conflict

Conflict Defined

[edit | edit source]Conflict can exist between factions or groups within a team, with a leader or manager, and with other teams or departments within the company. It has been defined in numerously different ways and has come to hold several connotations. The following is an example of a relatively broad dictionary entry, where conflict is defined in the following way(s):

Conflict

1. To come into collision or disagreement; be contradictory, at variance, or in opposition; clash: The account of one eyewitness conflicted with that of the other. My class conflicts with my going to the concert.

2. To fight or contend; do battle.

3. A fight, battle, or struggle, esp. a prolonged struggle; strife.

4. Controversy; quarrel: conflicts between parties.

5. Discord of action, feeling, or effect; antagonism or opposition, as of interests or principles: a conflict of ideas.

6. A striking together; collision.

7. Incompatibility or interference, as of one idea, desire, event, or activity with another: a conflict in the schedule.

8. Psychiatry. a mental struggle arising from opposing demands or impulses.

Conflict in Groups and Teams

[edit | edit source]Conflict inevitably arises in one form or another in varying degrees due to the mere group and/or team dynamics of having people with differing backgrounds, ideas, and potential agendas coming together in an effort to accomplish a common goal. Conflict is generally considered to be negative and something to be avoided. Numerous frameworks such as LaFasto and Larson's CONNECT model have been developed to help rid groups of negative conflict. However, conflict isn’t always negative and there are circumstances in which positive conflict is necessary in order to prevent compliance tendencies and the potentially disastrous effects of groupthink.

In the following sections, the positive and negative realms of conflict will be outlined and further detailed in an effort to narrow the scope of conflict while helping to navigate some of the more negative connotations that easily come to mind when thinking about conflict. Use all positive words and actions and you will get the same back, respect others and they will respect you.

Types of Conflict that a Team Can Face

[edit | edit source]Positive conflict vs Negative conflict

Positive conflict

[edit | edit source]

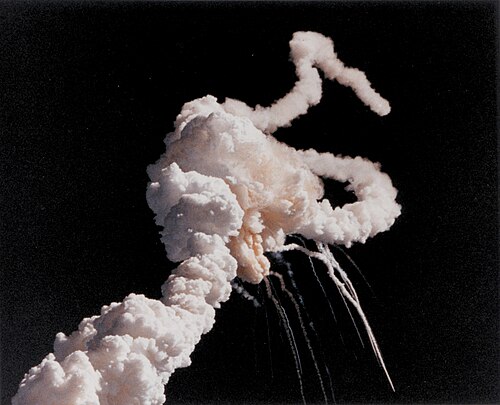

Positive conflict is the notion that a healthy discourse may exist in the disagreement among group members regarding personality traits, styles, or characteristics or the content of their ideas, decisions or task processes which involves a pathway towards resolution. Any tolerable amount of conflict is vital to group success in order to avoid groupthink and to generate more innovative ideas among potentially and vastly differing members of the group. In addition, positive conflict generates buy-in and offers elements of ownership and a sense of cooperation and enhanced membership to all of the group members. Positive conflict reduces the effects of conformity pressures and groupthink. Groupthink occurs when conformity and compliance pressures are exaggerated, and it generally occurs in the absence of task conflict. One of the most devastating examples of groupthink occurred on the morning of January 28th, 1986 in which the Challenger space shuttle exploded over the Atlantic Ocean after the failure of an O-ring. This failure resulted from the O-ring being unable to withstand extreme temperatures in which the O-ring had never been truly tested. Numerous NASA staff members were aware of the possible failure of the O-ring in extreme temperatures, and they were also aware of the ramifications should the O-ring break. However, the decision making process regarding whether or not the shuttle was safe to launch was riddled with flaws that ultimately created a breeding ground for groupthink. To illustrate, the Challenger launch had been postponed several times before this scheduled date, and there was direct pressure from NASA to approve the launch. There was also media pressure as they were scheduled to film the launch, since it would be the first time a teacher was sent into space. NASA officials feared public ridicule if the launch was delayed again, and as early as six days prior to the launch, NASA put the pressure on. They told the inspectors to stop thinking like inspectors and start thinking like managers, and they rationalized that there was no conclusive evidence to suggest that the O-ring would not work. As a result, the inspectors bowed to conformity pressures and gave the approval to launch. The resulting launch and subsequent death of all 7 crew members aboard the Challenger shook the nation and was not the front page news that NASA had hoped for.

Other disasters that occurred due to conformity pressures include the Bay of Pigs, the Tenerife plane crash disaster, the holocaust, and many others. To test how strong the effects of conformity pressures are on less cohesive groups and among individuals that were only recently introduced, Solomon Asch conducted his famous conformity experiment in which a group of random participants were shown a picture of the following lines, and they were asked which line in the second group of lines is approximately the same height as the first line shown.

Individuals that were a part of the experiment (confederates to the experiment) selected an obviously inappropriate line such as line “B” as their answer. The results were astounding in which the remaining individual in the group (not a confederate to the experiment) also selected line “B” as their answer due to perceived pressures to conform. Conformity occurs as a result of individuals’ desire to be liked and their need to be right. Therefore, they tend to fall victim to false consensus biases and generally bring their behavior in line with the group’s expectations and beliefs. So how are you to know if your group is falling prey to conformity pressures and groupthink? Here are some common symptoms:

- Illusions of invulnerability

- Rationalization & justification

- Illusion of group morality

- Stereotyping the out-group as weaker, evil, or stupid

- Direct or indirect peer or supervisory pressures

- Self-censorship by team members

- Illusions of unanimity

First, realizing that you and your group are affected by or susceptible to conformity pressures and groupthink is very important. Next, in order to create a norm of conflict, it is essential that a feeling of psychology safety is present. This can be instated by encouraging objections, criticisms, and altering perspectives. Also, as a leader, one should avoid making clear statements about your preferences, create subgroups, have outside experts come in to observe the decision making process, and re-examine the next best alternatives once a decision has been reached. Finally, limiting the size of the group and assigning roles that make conflict commonplace (such as a “Devil’s Advocate”) will help to discourage and minimize compliance pressures. After the Challenger explosion, NASA took similar steps to avoid future disasters in which they instituted a verbal and video recorded affirmation from several NASA officials that certify flight readiness. Furthermore, NASA's managers instituted a veto policy in which anyone at any level is given the authority to stop the flight process.

In addition to avoiding groupthink and conformity pressures, positive conflict is more likely to generate a sense of membership, involvement, and enthusiasm from all group members and is also more likely to lead to the infusion of more creative and innovative ideas. This results from each team member having the opportunity to voice his or her own perspective on the issues being decided by the group. When individuals feel more involved in the decision making process, they are more likely to state a high satisfaction level with their team and are additionally more likely to want to continue working as a member of that team.

Creating a heterogeneous team is another way to encourage diverse perspectives, opinions, and ideas. Heterogeneous groups also have a broader knowledge base resulting from a variety of experiences, backgrounds, skills, and achievements. Comparable to other investment strategies that are somewhat more risky (in terms of the increased likelihood for ensuing conflict levels), diverse teams stand a greater chance for potential return and favorable results as well.

Negative conflict

[edit | edit source]

In diverse and heterogeneous teams, negative conflict has a tendency to emerge in varying degrees due to the mere dynamics of having diverse individuals with differing backgrounds, ideas, and potential agendas coming together. Negative conflict can arise in several different arenas including the following:

- Conflict can arise between factions or groups within a team.

- Subgroups, or factions, can develop within a team. Each group has their own opinions and will stick together and oppose other factions within the team. Organizations can be greatly divided by such factions

- Conflict can develop between team members and the leader of the team.

- Team members can disagree with the team leader. This can lead to refusal to follow the direction of the team leader. There may be conflict with management because management has not given clear goals to the team or may not be supporting the team. The organization could have a culture that does not allow teams to work effectively.

- Conflict can form between the different teams or departments in the organization.

Unlike positive conflict, negative conflict is better if avoided and must be swiftly addressed and resolved when it does present itself. Due to the dangerous nature and destructive effects negative conflict has on productivity and moral, it may potentially lead to Human Resource Management issues or even a lawsuit. In order to set the stage so that interpersonal conflict is avoided or at least minimized, firms can prevent the establishment of in-groups and out-groups, foster open communication and trust, understand the various personality styles that comprise a group, and coach effective communication skills and perspective taking skills to team members.

An example of a firm, where the formation of in-groups and out-groups fostered so much negative conflict, was the Lehman Brothers firm, this in-group and out-group culture lead to the selling of the firm. Within this firm, a strong separation between Traders and Bankers literally divided the corporation and led to its ultimate demise. Differences between the functions were exaggerated and there was a perception that each of the divisions was pursuing its own unique and more valuable objectives. There was not a unified vision within the company and personality conflict was commonplace. The Traders believed that the Bankers were lazy "Ivy League" graduates who were awarded greater benefits simply to uphold the status-quo. The Bankers perceived the Brokers as less intelligent, blue collar workers who deserved less compensation and rewards. Creating in-groups and out-groups in a company leads to an unhealthy competition between the groups. Each faction ends up battling for a greater share of the company’s limited resources and an “us” vs. “them” rational emerges, while energy is wasted on trying to prove which group is better rather than to maintain common goals. As demonstrated by the infamous Robbers Cave Experiment conducted by Muzafer Sherif, working toward a common goal and maintaining common purpose is essential for group unity and contributes to the reduction of personal conflict. In this experiment, 22 boy scouts were assigned to two separate camps and neither group was aware of the other's existence. Each boy formed a strong identification with his own group, and the scouts were even allowed to select a group name. The first contact between the two groups was to play a competitive sport and friction emerged between the groups almost immediately. During the resolution phase of the experiment, a task was developed in which the two groups were forced to cooperate and work together toward achieving a common purpose that neither group could achieve alone. A broken-down truck that needed to be towed back to the camp was staged, and the two groups had to combine their man-power to tow the truck. By the end of the experiment, the in-groups and out-groups had merged, and the entire group even insisted upon riding back home on the same bus together. In addition to forming a super-ornate goal for group members to achieve, pointing out what group members have in common and defusing stereotypes is a way to prevent the formation of an out-group.

Fostering support, trust, and open communication is also essential if relationship conflicts are to be reduced and quickly resolved. Open communication can be established by the following:

- Establish ground rules.

- Take turns when talking and do not interrupt. Ensure that each team member has equal time when stating their perspective. Listen for something new and say bring something new to the discussion. Avoid restating the facts and “talking in circles.” Avoid power plays and eliminate status or titles from the discussion

- Listen compassionately

- Avoid thinking of a counterargument while the other person is speaking. Listen to the other person’s perspective rather than listening to your own thoughts. Don’t make an effort to remember points.

- Point out the advantages of resolving the conflict.

- Maintain a neutral vantage point and be willing to be persuaded.

- Avoid all-or-none statements such as “always” and “never” and point out exceptions when these statements are used.

- (IE: What does it look like when Marketing does consult sales before acting?)

- Create a goal of discovery rather than of winning or persuading.

- Be alert to common goals and where goals overlap as each party is communicating their perspective.

- Use clarifying statements to ensure the other party feels understood and listened to such as, “What I heard you say is that you feel unappreciated and that you lack vital feedback to help you perform, is this correct?”

- Help team members to separate the problem from the person.

- Use techniques such as role-playing, putting oneself in the competitor’s shoes, or conducting war games. Such techniques create fresh perspectives and engage team members.

- Team members should recognize each other for having expressed his view and feelings.

- Thanking one another recognizes the personal risk the individual took in breaking from group think and should be viewed as an expression of trust and commitment toward the team.

- Help each team member to understand one anothers' perspective, and help them to re-frame the situation.

- The exact same situation can often be viewed differently by several individuals. To illustrate, what did you see first in the picture below, the young woman or the old woman?

Once a team has received coaching on how to communicate effectively, address conflict situations immediately as they arise. Letting tense situations fester will only allow time for animosity to polarize and grow. Helping team members to reframe the problem and see it from the other individual’s perspective can also be accomplished directly, via cross-training and job shadowing which allows each team member to draw from a frame of reference by walking in the other team member's shoes. Utilizing the Big 5 personality test descriptions will also add an element of understanding to the group dynamic. To illustrate, if Jimmy is highly extroverted, neurotic, and conscientious, it may help Tim, who is not quite as extroverted as than Jim and who is more agreeable, to understand where Jimmy’s seemingly endless ability to voice his irritation with others is stemming from, and he may not take it as personally. In addition, Jimmy may better understand and get less irritated with Tim’s perceived inability to take initiative and make decisions efficiently.

Finally, understanding common stereotypes and mental shortcuts that are used when passing judgment on others will make team members more aware of how these shortcuts are leading to bias conclusions. The common cognitive biases and a brief description are as follows:

- Self Fulfilling Prophecy: the tendency to engage in behaviors that elicit results which will (consciously or subconsciously) confirm our beliefs.

- Halo Effect: the tendency for a person's positive or negative traits to "spill over" from one area of their personality to another in others' perceptions of them

- Primacy Effect: the tendency to weigh initial events more than subsequent events.

- Recency Effect: the tendency to weigh recent events more than earlier events

- Availability Heuristic: a biased prediction, due to the tendency to focus on the most salient and emotionally-charged outcome.

- Selective Perception: selectively attend to data that supports your conclusion while omitting valid evidence that does not.

- Actor-Observer Bias: the tendency for explanations for other individual's behaviors to overemphasize the influence of their personality and underemphasize the influence of their situation. This is coupled with the opposite tendency for the self in that one's explanations for their own behaviors overemphasize their situation and underemphasize the influence of their personality.

- Hindsight Bias: sometimes called the "I-knew-it-all-along" effect, the inclination to see past events as being predictable.

- Illusory Correlation: beliefs that inaccurately suppose a relationship between a certain type of action and an effect

- Egocentric Bias: occurs when people claim more responsibility for themselves for the results of a joint action than an outside observer would.

- False Consensus Bias: the tendency for people to overestimate the degree to which others agree with them.

- Fundamental Attribution Bias: the tendency for people to over-emphasize personality-based explanations for behaviors observed in others while under-emphasizing the role and power of situational influences on the same behavior

- Just World Phenomenon: the tendency for people to believe that the world is "just" and therefore people "get what they deserve."

- Self Serving Bias: the tendency to claim more responsibility for successes than failures. It may also manifest itself as a tendency for people to evaluate ambiguous information in a way beneficial to their interests

- Illusion of Transparency: people overestimate others' ability to know them, and they also overestimate their ability to know others.

- Ingroup Bias: the tendency for people to give preferential treatment to others they perceive to be members of their own groups.

“…If you form a picture in your mind of what you would like to be and hold it there long enough, you will soon become exactly as you have been thinking.” –William James, Professor of Psychology, Harvard University.

Why is Conflict Resolution Important in a Team Setting?

[edit | edit source]Whether we embrace it or avoid it, conflict is an inherent part of the human condition. Unlike certain tasks or responsibilities, conflict is not isolated to one or another aspect of life. With conflict looming all about us, why should we even bother trying to resolve it? Or, if conflict is inherent to being human, is it then presumptuous to even attempt its resolution? We propose that, in the vast majority of instances of team conflict, avoidance is a worse solution than engagement with the conflicting situation. Moreover, avoided conflict will lead to less optimal solutions and may even prevent the team from finishing a project. Thus, from a manager’s perspective, it is a simple equation of a cost/benefits analysis in that the cost to the organization is greater when teams avoid conflict than when they engage it. In this chapter we will discuss the symptoms of conflict and recommend solutions for their resolution.

Conflict absorbs team resources that could be better utilized working towards the team’s goals. As discussed, managers should manage conflict in a way that leads the team towards completion of team goals.

What are the Symptoms of Team Conflict?

[edit | edit source]Almost everyone has endured the experience of being part of a team that was plagued with conflict. Whether in a large group that erupts in anger and can’t finish a meeting, or a small group of two or three individuals that resort to backbiting and gossiping to vent frustration over a conflict, everyone has been a part of a team where conflict has gotten out of control. With this in mind, there are several symptoms of conflict that can be identified in groups which can help groups to recognize and manage conflict before it tears them apart. By identifying the following symptoms related to communication, trust, and opposing agendas, the team leader can identify conflict before it erupts. As you read through these symptoms, think of the teams that you are a part of and look for symptoms that exist in your team.

One common symptom of conflict is a lack of communication or a lack of respectful communication. This is most often seen when teams fail to have meaningful meetings. Most often, non-communicating meetings are characterized by team members sitting and listening to what the boss has to say. Often chatter or silence prevails in teams. A lack of communication can also be noted when team members don’t get along, and so refuse to talk to each other. These feuds create barriers within teams and prevent communication in the team. A lack of communication or disrespectful communication leads to a lack of trust, which is another symptom of team conflict. Teams that fail to produce desired results often lack the trust in one another as team members necessary to succeed. Without trust in a team, verbal or non-verbal conflict becomes the norm of the team. Team members spend more energy protecting their own positions and jobs then they do producing what is required for the team’s success. When trust erodes in a team, the habit of blaming others becomes the norm as individuals try to protect themselves. Team members become enemies that compete against each other rather than allies that build and help one another to achieve a common goal. Teams that lack trust often gossip about other members or have frequent side conversations after meetings to discuss opposing opinions. Such activity sucks strength out of the team and its purpose.

Another symptom of team conflict can be seen when team members have opposing agendas. This is not to be confused with members who have different opinions. Having different opinions in a group can be very healthy if managed correctly because it can create better ideas and ways of getting the job done. However, when team members have opposing agendas, more is at stake than differing opinions; it is two individuals fiercely committed to the exact opposite approach. Opposing agendas can create confusion in team members and can cause them to lose sight of their role in the team and the team’s final goal. Teams must work toward a common goal in order to be successful. Extreme effort must be made to reconcile differences, or such a team can look forward to failure.

What are Appropriate Solutions to Conflict?

[edit | edit source]As mentioned above, conflict is a natural and necessary element of a healthy team experience. If a team never experiences conflict, it is less likely to be as productive as a team that does experience conflict. This is especially true if the task that a team is attempting to complete is complex in nature or highly detailed. Without having members question specific actions, decisions, or the specifics of the proposed solution, it may appear to the team that there is only one way in which to solve the problem or complete the task.

One way in which a team can avoid being unproductive is by selecting members with different backgrounds. This can be difficult because people often assume that individuals who think similarly and get along with one another will be more productive when working together. But this is not necessarily true. In many cases having groups of people who think alike and are not willing to voice their disagreement can be detrimental, or even dangerous. Popular examples of this group think phenomenon are noted in the Kennedy Administration’s disaster with regards to the Bay of Pigs, or those involved with the Challenger shuttle launch. Differences among team members should however, be task orientated and not personal or relationship oriented. Relationship conflicts are rarely productive. If potential members of a team have a history of conflict due to relationships and not in relation to tasks, one or both should probably not be chosen as a team member. Additionally, peacekeepers should also be avoided, unless the team environment fosters a very safe atmosphere where the peacekeeper will feel comfortable enough to speak out in the team setting. In this case, a difference in opinion could be beneficial, but it might not be presented due to the member’s disproportionate desire to avoid conflict.

Avoiding the potential for group think, relationship conflicts, and peacekeepers in choosing team members will help to promote healthy conflict. But commitment is equally important. If team members are individually or collectively indifferent toward the overall goal, they probably will not perform well. A lack of commitment can also lead to a lack of conflict. If the team is committed to the overall goal and members are well chosen, there can be a healthy dose of conflict in the process to complete the task.

When conflict does occur, it is important to address it immediately. Although developing a solution to the conflict may take time, acknowledging it will help to ensure that it can become productive to the team. “Whatever the problem, effective teams identify, raise, and resolve it. If it’s keeping them from reaching their goal, effective teams try to do something about it. They don’t ignore it and hope it goes away.” By not addressing conflict, the leader risks sending the message that conflict is unmanageable and cause vested members to become complacent or feel their input is not valued. In the worst scenario, a conflict that is not resolved could go from being task orientated to personal.

How Can a Team Prevent Negative Conflict?

[edit | edit source]Conflict may be inevitable on a team and may even have a positive effect, “the absence of conflict is not harmony, it’s apathy.” However, most of us have had experience with the crippling side of conflict. In this section we offer insight into how other teams have successfully managed conflict and make recommendations for mechanisms to put into place in order to prevent harmful conflict. How do successful teams manage conflict?

Three business professors, who studied teams which had learned how to successfully “fight” in a team without allowing the conflict to become destructive, found some common themes as to how such teams function. First, successful teams worked with more, rather than less information and debated on the basis of facts. Second, teams developed multiple alternatives to enrich the level of debate. Third, productive teams shared commonly agreed upon goals and objectives. Fourth, teams injected humor into the decision-making process. Fifth, teams maintained a balanced power structure. And sixth, teams resolved issues without forcing consensus.

In another study, which surveyed 15,000 team members and their assessments of their team mates, two professors found that the most important behaviors in team relationships are openness and supportiveness, “Regardless of whether it was a working relationship with a peer, a superior, or a direct report, the result was the same. The two factors identified as most important were openness and supportiveness.” Moreover, the authors identify specifically what is meant by these two adjectives within a team context: openness “refers to the ability to surface and deal with issues objectively,” while supportiveness “refers to bringing out the best thinking and attitude in the other person.”

From the above insights into successful teams, we start to see that such teams put a high value on fact-based decisions and are able to set up mechanisms that bring out the best in each team member and facilitate information sharing. Drawing from these insights, then, what specific measures, should a new leader or newly formed team put into place to ensure the team can withstand conflict and even gain the benefits of creativity that comes out of conflict?

How Do Teams Prevent Damaging Conflict?

[edit | edit source]In order to prevent damaging conflict, the team leader must lay a conflict-friendly foundation for the team. The following approach will help the team leader to set the stage for conflict that is creative and productive:

- Set a clear goal for the team.

- Make expectations for team members explicit.

- Assemble a heterogeneous team, including diverse ages, genders, functional backgrounds, and industry experience.

- Meet together as a team regularly and often. Team members that don’t know one another well doesn’t know positions on the issues, impairing their ability to argue effectively. Frequent interaction builds the mutual confidence and familiarity team members require expressing dissent.

- Assign roles such as devil’s advocate and sky-gazing visionary and change these roles up from meeting to meeting. This is important to ensure all sides of an issue have been considered.

- Use techniques such as role-playing, putting oneself in the competitor’s shoes, or conducting war games. Such techniques create fresh perspectives and engage team members.

- Actively manage conflict. Don’t let the team acquiesce too soon or too easily. Identify and treat apathy early, and don’t confuse a lack of conflict with agreement.

Resolving Conflict

[edit | edit source]Interpersonal conflict should be managed and resolved before it degenerates into verbal assault and irreparable damage to a team. Dealing with interpersonal conflict can be a difficult and uncomfortable process. Usually, as team members, we use carefully worded statements to avoid frictions when confronting conflict.

The first step to resolving interpersonal conflict is in acknowledging the existence of the interpersonal conflict. Recognizing the conflict allows team members to build common ground by putting the conflict within the context of the larger goal of the team and the organization. Moreover, the larger goal can help by giving team members a motive for resolving the conflict.

The Rosetta Stone for dealing with conflict is communication. As team members we all understand the inevitability of interpersonal conflicts. Moreover, as we have established above, open and supportive communication is vital to a high performing team. One way to achieve this is by separating the problem from the person. Problems can be debated without damaging working relationships. When interpersonal conflict occurs, all sides of the issue should be recognized without finger-pointing or blaming. Above all, when team member gets yelled at or blamed for something, it has the effect of silencing the whole team. It gives the signal to everyone that dissent is not allowed, and, as we know, dissent is one of the most fertile resources for new ideas.

When faced with conflict, it is natural for team members to become defensive. However defensiveness usually makes it more difficult to resolve a conflict. A conflict-friendly team environment must encourage effective listening. Effective listening includes listening to one another attentively, without interruption (this includes not having side conversations, doodling, or vacant stares). The fundamentals to resolving team conflict include the following elements:

- Prior to stating one’s view, a speaker should seek to understand what others have said. This can be done in a few clarifying sentences,

- Seek to make explicit what the opposing sides have in common. This helps to reinforce what is shared between the disputants,

- Whether or not an agreement is reached, team members should thank the other for having expressed his view and feelings. Thanking the other recognizes the personal risk the individual took in breaking from group think and should be viewed as an expression of trust and commitment toward the team.

How Can Teams Resolve Conflict Between Factions?

[edit | edit source]In resolving conflict between factions, the team leader should start by bringing the groups together and acknowledging there is a conflict. The team leader should make sure all group members are clear about the group goal. Not only should each group member understand what the goal is, they each need to be willing to work toward achieving it.

Set ground rules for the group if this has not been done. An important rule to include is to eliminate outside politicking. When disagreements or issues arise, they should be discussed within the group. Factions should not have separate discussions about the problem. If ground rules have already been established, discuss whether all agree with them and are willing to follow them. Discuss the methods and processes that will be used to reach the team goal. Again, it is important to get all team members working together towards the common goal.

The team leader should stay alert to one faction forcing a particular solution. If such an instance arises, those forcing a solution should be asked to articulate the reason behind their thinking. Once the thinking has been articulated, there can be open discussion as to the merits and drawbacks to the proposed solution.

What Should a Team Leader Do To Resolve Conflict and Promote Team Performance?

[edit | edit source]Team leaders have the responsibility of resolving conflict within their teams. There are things that team leaders can do to make a team where conflict resolution occurs naturally. One thing that team leaders can do in their groups to resolve conflict is to set up team rules from the outset. As discussed earlier, such team rules can guide team members to resolve conflict between themselves, rather than going to the leader to resolve all conflict. Team leaders should foster an environment in their teams that is safe and positive. Such an environment will help foster communication and will help team members to resolve conflicts. Team leaders can also provide retreats and other activities away from the office that will help to build team unity and trust. These factors will also strengthen a team and help to avoid negative conflict before it begins.

Team leaders can also strictly monitor performance issues in their group. Performance issues that go unresolved create relationship conflict and a lack of motivation and morale. Performance issues in individual team members must be addressed immediately in order to avoid issues in the group. This doesn’t mean that team leaders always need to eliminate poor performing team members immediately. Sometimes it is the responsibility of the team leader to provide extra training to team members when they’re struggling, to help them meet expectations. When attitudes need to be changed, awareness can be brought to how a team member’s attitude negatively affects the team and invitations can be given for attitudes to improve.

In this process it is vital for the team leader to remember that accountability must be held with team members. Without accountability in a team, focus on the goal will not occur and teams won’t produce desired outcomes. Accountability promotes achievement and helps team members to reach their potential. A lack of accountability can produce great task conflict and relationship conflict. Full accountability can help produce a feeling of fulfillment and achievement and teams will achieve their optimal performance.

How Can a Team Member Resolve a Conflict with the Team Leader?

[edit | edit source]If a team member has a conflict with the team leader, the first step is to identify the type of conflict. If the conflict relates to the goal of the team, then it would appear that the goal is not clear. The conflict can also relate to the processes being used by the team. In either situation, the team member can bring up the issue in a group meeting. Ask that the goal be clarified so that all team members understand what it is. If processes were never discussed and decided on by the team, now would be an appropriate time to do so. If the team leader does not want to discuss these issues in a team meeting, the team member should approach the leader separately to discuss. The team member should explain the issue and why the current situation is not working. Again, ask that the team be allowed to discuss these issues.

If the conflict is interpersonal between the team leader and a team member, the issue should be discussed privately between the two. The team member should go to the leader and explain that there appears to be conflict and that he or she would like to resolve it. LaFasto and Larson outline an approach that can be used to resolve conflict called the Connect Model. The steps involved in the model are as follows:

- Commit to the relationship.

- Optimize safety.

- Narrow to one issue.

- Neutralize defensiveness.

- Explain and echo.

- Change one behavior each.

- Track it!

These steps provide a great review of what has been discussed throughout this chapter and will help to resolve the issue between a team leader and team member.

In summary, team conflict is an important and integral part of any team that exists. As we have outlined it in this chapter, conflict, if approached effectively and managed appropriately, can exponentially work in the favor of any team. Appropriate management of the relative type of team conflict at hand is critical for teams to be successful. This chapter has discussed several of the aspects of team conflict and how they can be best managed and potentially resolved. These concepts will help teams improve their functionality and dynamic effectiveness in an effort to reach their ultimate goals in reaching to be a high performing team.

References

[edit | edit source]- Greenhalgh, Leonard. "Managing Conflict." Sloan Management Review (Summer 2006): 45-51.

- Lafasto, Frank, and Carl Larson. "When teams Work Best". Thousand Oaks, CA.: Sage Publications, 2001. ISBN 0-7619-2366-7

- Siegel, Matt. "The Perils of Culture Conflict." Fortune. November 1998: 257-262.

- Simons, Tony L., and Randall S. Peterson. "Task Conflict and Relationship Conflict in Top Management Teams: The Pivotal Role of Intragroup Trust". Journal of Applied Psychology. 85.1 (2000): 102-111.

- Taylor, Susan M. "Manage Conflict Through Negotiation and Mediation." The Blackwell Handbook of Principles of Organizational Behavior, 2003. ISBN 9780631215066.

- Weingart, Laurie, and Karen A. Jehn. "Manage Intra-Team Conflict Through Collaboration." The Blackwell Handbook of Principles of Organizational Behavior, 2003. ISBN 9780631215066.