Nanotechnology/Semiconducting Nanostructures

| Navigate |

|---|

| << Prev: Overview of Production methods |

| >< Main: Nanotechnology |

| >> Next: Metallic Nanostructures |

Nanotubes

[edit | edit source]Certain compounds are capable of forming nanotubes where the tube consists of round shell of a single layer of atoms in a cylindrical lattice. Carbon nanotubes is the most famous example, but also other materials can form nanotubes such as Boron-nitride, Molybdenum sulfide and others.

Nanotubes can also be made by etching the core out of an shell structured rod, but such tubes will normally contain many atomic layers in the wall and have crystal facets on the sides.

Carbon Nanotubes

[edit | edit source]Carbon nanotubes are fascinating nanostructures. A sheet of graphene as in common graphite, but rolled up in small tubes rather than planar sheets.

Carbon nanotubes have unique mechanical properties such as high strength, high stiffness, and low density [1] and also interesting electronic properties. A single-walled carbon nanotube can be either metallic or semiconducting depending on the atomic arrangement [2].

This section is a short introduction to carbon nanotubes. For a broader overview the reader is referred to one of the numerous review articles or books on carbon nanotubes

Geometric Structure

[edit | edit source]The simplest type of carbon nanotube consists of just one layer of graphene rolled up in the form of a seamless cylinder, known as a single-walled carbon nanotube (SWCNT) with a typical diameter of just a few nanometers. Larger diameter nanotube structures are nanotube ropes, consisting of many individual, parallel nanotubes closed-packed into a hexagonal lattice, and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) consisting of several concentric cylinders nested within each other.

Single walled Carbon Nanotube

[edit | edit source]The basic configuration is thus the SWCNT. Its structure is most easily illustrated as a cylindrical tube conceptually formed by the wrapping of a single graphene sheet. The hexagonal structure of the 2-dimensional graphene sheet is due to the hybridization of the carbon atoms, which causes three directional, in-plane bonds separated by an angle of 120 degrees.

The nanotube can be described by a chiral vector that can be expressed in terms of the graphene unit vectors and as with the set of integers uniquely identifying the nanotube. This chiral vector or 'roll-up' vector describes the nanotube circumference by connecting two crystallographically equivalent positions i.e. the tube is formed by superimposing the two ends of .

Based on the chiral angle SWCNTs are defined as zig-zag tubes (), armchair tubes (), or chiral tubes ().

Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes

[edit | edit source]MWCNTs are composed of a number of SWCNTs in a coaxial geometry. Each nested shell has a diameter of where is the length of the carbon-carbon bond which is 1.42 Å. The difference in diameters of the individual shell means that their chiralities are different, and adjacent shell are therefore in general non-commensurate, which causes only a weak intershell interaction.

The intershell spacing in MWCNTs is 0.34 nm - quite close to the interlayer spacing in turbostratic graphite [6]

Electronic Structure

[edit | edit source]The electronic structure of a SWCNT is most easily described by again considering a single graphene sheet. The 2-D, hexagonal-lattice graphene sheet has a 2-D reciprocal space with a hexagonal Brillouin zone (BZ).

The bonds are mainly responsible for the mechanical properties, while the electronic properties are mainly determined by the bands. By a tight-binding approach the band structure of these bands can be calculated [7]

Graphene is a zero-gap semiconductor with an occupied band and an unoccupied band meeting at the Fermi level at six points in the BZ, thus it behaves metallic, a so-called semimetal.

Upon forming the tube by conceptually wrapping the graphene sheet, a periodic boundary condition is imposed that causes only certain electronic states of those of the planar graphene sheet to be allowed. These states are determined by the tube's geometric structure, i.e. by the indices of the chiral vector. The wave vectors of the allowed states fall on certain lines in the graphene BZ.

Based on this scheme it is possible to estimate whether a particular tube will be metallic or semiconducting. When the allowed states include the point, the system will to a first approximation behave metallic. However, in the points where the and the bands meet but are shifted slightly away from the point due to curvature effects, which causes a slight band opening in some cases [8]

This leads to a classification scheme that has three types of nanotubes:

- Metallic: These are the armchair tubes where the small shift of the degenerate point away from the point does not cause a band opening for symmetry reasons.

- Small-bandgap semiconducting: These are characterized by with being an integer. Here, the wave vectors of the allowed states cross the point, but due to the slight shift of the degenerate point a small gap will be present, the size of which is inversely proportional to the tube diameter squared with typical values between a few and a few tens meV

- Semiconducting: In this case . This causes a larger bandgap, the size of which is inversely proportional to the tube diameter: with experimental investigations suggesting a value of of 0.7-0.8 eV/nm

Typically the bandgap of the type 2 nanotubes is so small that they can be considered metallic at room temperature. Based on this it can be inferred that 1/3 of all tubes should behave metallic whereas the remaining 2/3 should be semiconducting. However, it should be noted that due to the inverse proportionality between the bandgap and the diameter of the semiconducting tubes, large-diameter tubes will tend to behave metallic at room temperature. This is especially important in regards to large-diameter MWCNTs.

From a electrical point of view a MWCNT can be seen as a complex structure of many parallel conductors that are only weakly interacting. Since probing the electrical properties typically involves electrodes contacting the outermost shell, this shell will be dominating the transport properties [11] In a simplistic view, this can be compared to a large-diameter SWCNT, which will therefore typically display metallic behavior.

Electrical and Electromechanical Properties

[edit | edit source]Many studies have focused on SWCNTs for exploring the fundamental properties of nanotubes. Due to their essentially 1-D nature and intriguing electronic structure, SWCNTs exhibit a range of interesting quantum phenomena at low temperature [12]

The discussion here will so far, however, primarily be limited to room temperature properties.

The conductance of a 1-dimensional conductor such as a SWCNT is given by the Landauer formula [13]

,

where ;

is the conductance quantum;

and is the transmission coefficient of the contributing channel .

More information on nanotubes

[edit | edit source]Commercial suppliers of carbon nanotubes and related products

[edit | edit source]- Nanoledge.com nanotubes and related products - fibers, pellets, resins and dispersions...

- Carbon Solution, Inc. Mainly SWCNT.

- BuckyUSA Fullerens, SWCNT, MWCNT.

- CNI HiPco Carbon nanotubes

- Carbolex SWCNT,sub-gram quantities are sold via sigma aldric

- Sigma-Aldrich SWCNT

"Buckyball"

[edit | edit source]

Buckminsterfullerene (IUPAC name (C60-Ih)[5,6]fullerene) is the smallest fullerene molecule in which no two pentagons share an edge (which can be destabilizing, as in pentalene). It is also the most common in terms of natural occurrence, as it can often be found in soot.

The structure of C60 is a truncated (T = 3) icosahedron, which resembles a soccer ball of the type made of twenty hexagons and twelve pentagons, with a carbon atom at the vertices of each polygon and a bond along each polygon edge.

The w:van der Waals diameter of a C60 molecule is about 1 nanometer (nm). The nucleus to nucleus diameter of a C60 molecule is about 0.7 nm.

The C60 molecule has two bond lengths. The 6:6 ring bonds (between two hexagons) can be considered "double bonds" and are shorter than the 6:5 bonds (between a hexagon and a pentagon). Its average bond length is 1.4 angstroms.

Silicon buckyballs have been created around metal ions.

Boron buckyball

[edit | edit source]A new type of buckyball utilizing boron atoms instead of the usual carbon has been predicted and described by researchers at Rice University. The B-80 structure, with each atom forming 5 or 6 bonds, is predicted to be more stable than the C-60 buckyball.[14] One reason for this given by the researchers is that the B-80 is actually more like the original geodesic dome structure popularized by Buckminster Fuller which utilizes triangles rather than hexagons. However, this work has been subject to much criticism by quantum chemists[15][16] as it was concluded that the predicted Ih symmetric structure was vibrationally unstable and the resulting cage undergoes a spontaneous symmetry break yielding a puckered cage with rare Th symmetry (symmetry of a volleyball)[15]. The number of six atom rings in this molecule is 20 and number of five member rings is 12. There is an additional atom in the center of each six member ring, bonded to each atom surrounding it.

Variations of buckyballs

[edit | edit source]Another fairly common buckminsterfullerene is C70,[17] but fullerenes with 72, 76, 84 and even up to 100 carbon atoms are commonly obtained.

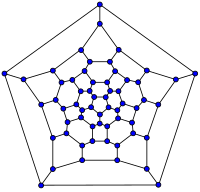

In mathematical terms, the structure of a fullerene is a trivalent convex polyhedron with pentagonal and hexagonal faces. In graph theory, the term fullerene refers to any 3-regular, planar graph with all faces of size 5 or 6 (including the external face). It follows from Euler's polyhedron formula, |V|-|E|+|F| = 2, (where |V|, |E|, |F| indicate the number of vertices, edges, and faces), that there are exactly 12 pentagons in a fullerene and |V|/2-10 hexagons.

|

|

|

|

| 20-fullerene (dodecahedral graph) |

26-fullerene graph | 60-fullerene (truncated icosahedral graph) |

70-fullerene graph |

The smallest fullerene is the w:dodecahedron--the unique C20. There are no fullerenes with 22 vertices.[18] The number of fullerenes C2n grows with increasing n = 12,13,14..., roughly in proportion to n9. For instance, there are 1812 non-isomorphic fullerenes C60. Note that only one form of C60, the buckminsterfullerene alias w:truncated icosahedron, has no pair of adjacent pentagons (the smallest such fullerene). To further illustrate the growth, there are 214,127,713 non-isomorphic fullerenes C200, 15,655,672 of which have no adjacent pentagons.

w:Trimetasphere carbon nanomaterials were discovered by researchers at w:Virginia Tech and licensed exclusively to w:Luna Innovations. This class of novel molecules comprises 80 carbon atoms (C80) forming a sphere which encloses a complex of three metal atoms and one nitrogen atom. These fullerenes encapsulate metals which puts them in the subset referred to as w:metallofullerenes. Trimetaspheres have the potential for use in diagnostics (as safe imaging agents), therapeutics and in organic solar cells.[citation needed]

Semiconducting nanowires

[edit | edit source]Semiconducting nanowires can be made from most semiconducting materials and with different methods, mainly variations of a chemical vapor deposition process (CVD).

There are many different semiconducting materials, and heterosrtuctures can be made if the lattice constants are not too incompatible. Heterostructures made from combinations of materials such as GaAs-GaP can be used to make barriers and guides for electrons in electrical systems.

Low pressure metal organic vapor phase epitaxy (MOVPE) can be used to grow III-V nanowires epitaxially on suitable crystalline substrates, sucha s III-V materials or silicon with a reasonably matching lattice constant.

Nanowire growth is catalyzed by various nanoparticles, which are deposited on the substrate surface, typically gold nanoparticles with a diameter of 20-100nm.

To grow for instance GaP wires, the sample is typically annealed at 650C in the heated reactor chamber to form an eutectic with between the gold catalyst and the underlying substrate.

Then growth is done at a lower temperature around 500C in the presence of the precursor gasses trimethyl gallium and phosphine. By changing the precursor gasses during growth, nanowire heterostructures with varying composition can be made

Resources

[edit | edit source]Nanoparticles

[edit | edit source]Catalytic particles

[edit | edit source]Commercial suppliers of nanoparticles

[edit | edit source]- Reade has a wide selection of nanoparticles

- sigma-aldrich has dispersions of nanoparticles

- nanophase

Contributors and Acknowledgements

[edit | edit source]- Jakob Kjelstrup Hansen

References

[edit | edit source]See also notes on editing this book about how to add references Nanotechnology/About#How_to_contribute.

- ↑ qian2002

- ↑ hamada1992

- ↑ avouris2003

- ↑ dresselhaus2001

- ↑ saito1998

- ↑ dresselhaus2001

- ↑ saito1998

- ↑ hamada1992.

- ↑ zhou2000

- ↑ wildoer1998,odom1998

- ↑ frank1998

- ↑ nygard1999,dresselhaus2001

- ↑ datta1995

- ↑ Bucky's brother -- The boron buckyball makes its début Jade Boyd April 2007 eurekalert.orgLink

- ↑ a b The boron buckyball has an unexpected Th symmetry G. Gopakumar, Nguyen, M. T., Ceulemans, Arnout, Chem. Phys. lett. 450, 175, 2008.[1]

- ↑ "Stuffing improves the stability of fullerenelike boron clusters" Prasad, DLVK; Jemmis, E. D.; Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 165504, 2008.[2]

- ↑ Buckminsterfullerene: Molecule of the Month

- ↑ Goldberg Variations Challenge: Juris Meija, Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006 (385) 6-7