New Zealand History/Print version

| This is the print version of New Zealand History You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

Introduction to A Concise New Zealand History

This is a concise textbook on New Zealand history, designed so it can be read by virtually anyone wanting to find out more about New Zealand history.

The textbook covers the time span of human settlement in New Zealand. It includes:

- The discovery and colonisation of New Zealand by Polynesians.

- Maori culture up to the year 1840.

- Discovery of New Zealand by Europeans.

- Early New Zealand economy and Missionaries in New Zealand.

- The Treaty of Waitangi.

- European colonisation, and conflict with the Maori people.

- Colonial, Twentieth Century and Modern Government.

- Important events in the twentieth century and recent times.

Find out how events in New Zealand's humble beginnings have shaped the way the country is in the present day.

PART 1: EARLY HISTORY

Polynesian Settlement of New Zealand

Around 950 AD, it is believed Polynesian settlers used subtropical weather systems, star constellations, water currents, and animal migration to find their way from their native islands, in central Polynesia to New Zealand. As the settlers colonized the country, they developed their distinctive Māori culture.

According to Māori, the first Polynesian explorer to reach New Zealand was Kupe, who traveled across the Pacific in a Polynesian-style voyaging canoe. It is thought Kupe reached New Zealand at Hokianga Harbour, in Northland, about 1070 years ago.

Although there has been much debate about when and how Polynesians actually started settling New Zealand, the current understanding is that they migrated from East and central Polynesia, the Southern Cook and Society islands region. They migrated deliberately, at different times, in different canoes, first arriving in New Zealand in the late 10th Century.

For a long time during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, it was believed the first inhabitants of New Zealand were the Moriori people, who hunted giant birds called moas. The theory then established the idea that the Māori people migrated from Polynesia in a Great Fleet and took New Zealand from the Moriori, establishing an agricultural society. However, new evidence suggests that the Moriori were a group of mainland Māori who migrated from New Zealand to the Chatham Islands, developing their own distinctive, peaceful culture. During the w:Moriori Genocide, most of the Moriori were killed or enslaved, with few remaining today.

Maori Culture and Lifestyle up to 1840

Polynesians had arrived in Aotearoa (the Land of the Long White Cloud) i.e. New Zealand, around 1250 AD. At that point, having come from a tropical region, they had to dramatically change their lifestyle to suit the new environment.

Some of the biggest changes the Polynesians had to adapt to was that New Zealand was much larger and had a more temperate climate than the islands they had migrated from. This meant they had to build houses on the ground instead of on stilts to make them warmer, they had to develop much warmer clothing. New ways to hunt, fish, build, adapt. The Polynesians became a new group of people who eventually were called Maori (by Europeans) although 'Maori' referred to themselves as 'Tangata Whenua' i.e. People of the Land.

Maori as a people were known amongst themselves by their Iwi (Tribal) affiliations which often reflected the particular 'Waka' (or canoe) the individual could trace his oral history or lineage back to. Inter-marriage between Iwi was a way of strengthening alliances between various tribal groupings. Within Iwi (tribal groups) smaller family groups or sub-tribes (Hapu) was organized. Men had full faced tattoos (moko) which reflected this identity, as well as other attributes, such as status, bravery etc. Women also had tattooing on lower-lips and chins which also represented both lineage 'whakapapa', and status. This art of tattooing was highly sacred (Tapu), as were many other aspects of Maori culture such as canoe building, carving, hunting etc.

The first Maori settlements were mostly located around harbours or river mouths where fish and seabirds lived.

New Zealand, unlike their original islands, was abundant in wild game, so the Maori used both agriculture and hunting to sustain the Iwi. One of their biggest sources of food was the Moa, a large flightless bird. The Moas varied in size from the height of a turkey to 3.7 metres high. Unfortunately, this made them easy targets, and they became extinct due to over-hunting by about 1500. As a result of this, the Maori switched back to agriculture.

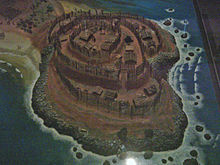

Gradually, the Maori dispersed themselves over New Zealand in different tribes, with different chiefs as leaders. The different tribes became more aggressive, however, and inter-tribal warfare became much more frequent over time. This led to the advent of the Pa (a fortified village). An average Pa included ditches, banks and Palisades as protection.

New Zealand eventually became divided up by tribal territories which were recognised by other tribes with predominant land features (rivers, mountains, lakes). This culture remained up until the 18th Century when the Europeans came to New Zealand.

After the first European whalers and traders came to New Zealand, the Maori lifestyle in some areas changed dramatically, and never returned to the way it was. One of the most popular commodities the Maori were interested in trading for were muskets. As Maoris had no long-range weapons, muskets were a valuable asset to tribes. The introduction of muskets made inter-tribal wars far more dangerous, especially if it was a tribe with muskets against a tribe without.

Before the arrival of Missionaries, Maori culture included their own religion, but when Europeans arrived that all changed, and Maoris were gradually converted to Christianity.

A written form of the Maori language was also created for the Maori by the Missionaries, and gradually the Maori culture became something completely different than before.

PART 2: EUROPEAN EXPLORATION AND SETTLEMENT

First European Explorers to Discover New Zealand

Abel Tasman

Abel Tasman, a Dutch explorer, was one of the first Europeans to discover New Zealand on the 13th of December 1642, in his search for the Great Southern Continent. Tasman noted in his journal that it was a large land, uplifted high (the area he sighted was near the Southern Alps). He called New Zealand 'Staten Landt' which refers to the 'Land of the (Dutch) States-General'.

The first encounter Tasman had with the Maori was on the 18th of December in Taitapu Bay (now Golden Bay), when two canoes from the shore approached Tasman's ship. Communication was not possible, as the Dutch and the Maori couldn't understand each other's languages.

Later, more canoes approached the ship, so the Dutch sent out a boat to tempt the Maori to come on board. One of the canoes rammed the small Dutch boat, killing some sailors. The Dutch, in turn, fired at the Maori when more canoes approached, causing the Maori to retreat to shore rapidly.

After this, Tasman travelled to the tip of the North Island before leaving New Zealand waters.

James Cook

British explorer, James Cook, captain of the Endeavour entered New Zealand waters on the 6th of October 1769, and laid anchor at today's Poverty Bay. When Cook saw smoke, he realised the land was inhabited, he and a group of sailors headed to shore, in the hope of befriending the natives and taking on board refreshments. The Maori were hostile, however, and the British had to fire on the Maori in self-defence.

Cook attempted trade with Maori again at a different location, but with no success. He managed to sketch 2400 miles of coastline on the journey and proved New Zealand was not part of a major continent. He returned to New Zealand another two times in the 18th Century.

Jean-Francois-Marie de Surville

Jean Francois Marie De Surville, was a captain of the French East India Company ship, Saint Jean Baptiste. He entered New Zealand Waters on the 12th of December 1769, 11:15am, off the Coast of Hokianga. On 16th of December, the French Ship rounded North Cape. Captain James Cook and Captain Jean propably passed within 20 to 25Km from each other. One Day later, on the 17th, Jean discovered what he called 'Lauriston Bay', Unbeknown to him, Captain James Cook had already named it 'Doubtless Bay'. From the 18th to the 31st of December, Jean anchored off North of Doubtless Bay. At that point, Maori Waka rowed out to him, and begun the first acts of Trade in New Zealand.

However, peacefully relations between the Maori and the French didn't last. Two days later, Jean perceived that the Maori were stealing a Boat which had drifted ashore. In retaliation, Jean Burned down various Huts, food stores, nets and Canoes. Soon after, he took prisoner of the Ngati Kahu leader, Ranginui. Unfortunately, Ranginui died out at sea, on the 24th of March 1770.

Jean Francois Marie De Surville Confirmed the Non-existence of Davis Land otherwise known as Terra Australias. This mythical Southern continent was hypothesised to 'Balance' the earth.

A New Economy Introduced to New Zealand

For 50 years after Sydney was founded in 1788, New Zealand became an economic outpost of New South Wales. New Zealand's main European based economy at the time was built around whaling, sealing, farming and trade with the Maori people.(১৭৮৮ সালে সিডনি প্রতিষ্ঠিত হওয়ার পর ৫০ বছর ধরে নিউজিল্যান্ড নিউ সাউথ ওয়েলসের একটি অর্থনৈতিক ফাঁড়িতে পরিণত হয়। তৎকালীন নিউজিল্যান্ডের প্রধান ইউরোপীয় ভিত্তিক অর্থনীতি তিমি শিকার, সিলিং, কৃষিকাজ এবং মাওরি জনগণের সাথে বাণিজ্যকে কেন্দ্র করে নির্মিত হয়েছিল।)

Whaling in New Zealand

For the first forty years of the 19th Century, whaling was the biggest economic activity for Europeans that came to New Zealand.(১৯ শতকের প্রথম চল্লিশ বছর ধরে, নিউজিল্যান্ডে আসা ইউরোপীয়দের জন্য তিমি শিকার ছিল সবচেয়ে বড় অর্থনৈতিক কর্মকাণ্ড।)

At the time in Europe, whales were needed for their oil (street lighting, frying food, oiling instruments), so the whaling industry in New Zealand was highly successful. The first whaling ship, the William Ann, was in New Zealand waters by around 1791–92, and many whaling ships arrived at New Zealand by the year 1800, most of them being British, American or French. Even some Maori joined whaling crews for new experiences.(সেই সময় ইউরোপে, এদের তেলের জন্য তিমির চাহিদা ছিল (রাস্তার আলো, ভাজা খাবার, যন্ত্রে ব্যবহৃত তেল) তাই নিউজিল্যান্ডের তিমি শিকার শিল্প অত্যন্ত সফল ছিল। প্রথম তিমি শিকারি জাহাজ, উইলিয়াম অ্যান প্রায় ১৭৯১-৯২ সাল পর্যন্ত নিউজিল্যান্ডের পানিতে বিচরণ করে। ১৮০০ সালের মধ্যে অনেক তিমি শিকারি জাহাজ নিউজিল্যান্ডে আসে, তাদের বেশিরভাগই ছিল ব্রিটিশ, আমেরিকান বা ফরাসি। এমনকি কিছু মাওরি নতুন অভিজ্ঞতার জন্য তিমি শিকারিদের দলে যোগ দিয়েছিলো।)

Sealing

The first major sealing operation in New Zealand was in Dusky Sound, November 1792, in which men were dropped off from the ship Britannia, to gather skins of Fur Seals for the China market as payment for tea. By September 1793, when the men were picked up again, they had 4500 skins.(নিউজিল্যান্ডের প্রথম মুখ্য সীল শিকার অভিযানটি হয়েছিল ১৭৯২ সালের নভেম্বরে ডাস্কি সাউন্ডে, যেখানে ব্রিটানিয়া জাহাজ থেকে পুরুষদের নামিয়ে দেওয়া হয়েছিল, চায়ের মূল্য হিসাবে চীনা বাজারের জন্য পশমি সীলের চামড়া সংগ্রহ করতে। ১৭৯৩ সালের সেপ্টেম্বরের মধ্যে, যখন তাদের আবার তুলে নেওয়া হয়, তখন তাদের কাছে ৪৫০০ চামড়া ছিল।)

Sealing was revived in 1803, when the seal colonies in Bass Strait, Australia, had been exhausted. Seals were still in high demand, for hats, and the leather for shoes. Furthermore, seal oil burned without smoke or smell and was needed for lighting and some industrial processes.(অস্ট্রেলিয়ার বাস স্ট্রেইটে সীল শিকারি উপনিবেশগুলি নিঃশেষ হয়ে যাওয়ায়, ১৮০৩ সালে (নিউজিল্যান্ড এ) সীল শিকার পুনরুজ্জীবিত হয়েছিল। টুপি এবং জুতোর জন্য তখনও সীলের চামড়ার উচ্চ চাহিদা ছিল। উপরন্তু, সীলের তেল ধোঁয়া বা গন্ধ ছাড়াই পুড়ত এবং আলো ও কিছু শিল্প প্রক্রিয়ার জন্য এর প্রয়োজন ছিল।)

There was a rush for seals in Dusky Sound and the West Coast in the early nineteenth century, and the seals were hunted to the verge of extinction by 1830. Sealing in New Zealand was finally outlawed in 1926.(ঊনবিংশ শতাব্দীর গোড়ার দিকে ডাস্কি সাউন্ড এবং পশ্চিম উপকূল সীলের জন্য সরগরম ছিল এবং ১৮৩০ সাল পর্যন্ত সীলগুলি, বিলুপ্তির সীমান্ত পর্যন্ত শিকার করা হয়েছিল। অবশেষে ১৯২৬ সালে নিউজিল্যান্ডে সীল শিকার নিষিদ্ধ করা হয়।)

Trade with the Maori People

The first European ‘town’ grew at Kororāreka, when European whalers started calling into the Bay of Islands for food and water. From the 1790s Maoris started to produce pork and potatoes to trade to the Europeans. The presence of Europeans drew Maoris to European towns. The Maoris were quick to catch on the benefits of trade and were eager for Europeans to live among them. They were especially interested in acquiring firearms.(কোরারেকায় প্রথম ইউরোপীয় 'শহর' গড়ে ওঠে, যখন ইউরোপীয় তিমি শিকারীরা খাদ্য ও জলের জন্য বে অফ আইল্যান্ড -এ আসতে শুরু করে। ১৭৯০-এর দশক থেকে মাওরিরা ইউরোপীয়দের সাথে বাণিজ্য করার জন্য শুয়োরের মাংস এবং আলু উৎপাদন শুরু করে। ইউরোপীয়দের উপস্থিতি মাওরিদের ইউরোপীয় শহরগুলিতে আকৃষ্ট করেছিল। মাওরিরা বাণিজ্যের সুবিধাগুলি দ্রুত বুঝতে পেরেছিল এবং ইউরোপীয়রা তাদের মধ্যে বসবাস করতে আগ্রহী ছিল। তারা বিশেষ করে আগ্নেয়াস্ত্র ক্রয় করতে আগ্রহী ছিল।)

Missionaries Dispatched to New Zealand

The Church Missionary Society was one of the earliest organisations to dispatch missionaries to New Zealand. In 1813, one of New Zealand's well known early missionaries, Samuel Marsden, asked the CMS to fund a mission to New Zealand. He had been impressed with the Maoris he had met in New South Wales on an earlier occasion, and felt that they needed to be evangelised. He succeeded in gathering together a band of settlers to accompany him, including a teacher and a joiner. However, Marsden had to finance his own ship to New Zealand.

Due to bureaucratic problems, the earliest missionaries arrived in New Zealand at the Bay of Islands in 1814. The mission had two main goals: Christianisation of the Maori people and the attempt to try and keep law and order among the European settlers.

The first Christian Mission Station in New Zealand was set up by Marsden in the Bay of Islands, the same year they arrived. However, the missionaries arrived to a violent atmosphere. Maori were busy trading with settlers for muskets to use on other tribes, and even the missionaries were beginning to argue amongst themselves. Marsden was also experiencing problems with the governor in New South Wales, who was treating the Mission as a bit of a joke. The missions became more successful, however, as time progressed.

In 1819, a block of land in Kerikeri was purchased to set up a new Mission Station at Paihia, which Reverend Henry Williams operated. Williams became highly respected among Nga Puhi, and prevented fighting on several occasions. Missionary influence also put an end to slavery and cannibalism among the Maori. The first baptism of a Maori in New Zealand was conducted in 1825.

Between 1834 and 1840, Mission Stations were established at Kaitaia, Thames, Whangaroa, Waikato, Mamamata (which was abandoned during tribal wars in 1836-37), Rotorua, Tauranga, Manukau and Poverty Bay. By 1840, over 20 Stations had been established, many of which were based in the North Island.

Maori learnt much from missionaries. Not only did they learn about Christianity, but they also learnt European farming techniques and trades and how to read and write. Missionaries also transcribed the Maori language into written form. For many Maori, missionaries were the first contact they had with Europeans, so the missionaries wanted to leave a good impression with the Maoris.

In 1838, a report indicated that the Church Missionary Society stations were staffed with five ministers, 20 catechists, a farmer, a surgeon, an editor, a printer, a wheelwright, a stonemason, two assistant teachers and two female teachers.

Mission Stations customarily consisted of a house for the Missionary's family, a school room, a chapel, a sleeping quarters for school children and Maoris who were being trained as teachers. A farm and orchard were often attached. From the Mission Stations, Missionaries could visit a circuit of Maori villages by foot.

The Missionary William Yate began printing in Maori in the early 1830s. The Church Missionary Society later sent a trained printer, William Colenso, and a printing press to Paihia, enabling Maori bibles to be printed in New Zealand. The first complete New Testament bible in Maori was printed in 1837. By 1840, much of the Old Testament had also been translated into Maori by William Williams and Robert Maunsell. Many copies of the translated bible were distributed direct from the printing press in Paihia.

French Missionary Efforts

In the 1830s, French missionaries introduced Catholicism to the Maoris. Jean Baptiste François Pompallier was one of the main missionaries behind this movement. Pompallier was appointed the first vicar apostolic of Western Oceania, and arrived in New Zealand at Hokianga on the 10th of January 1838. He came with one priest, one brother, a small supply of goods, but very little money. Unfortunately for Pompallier, most of the Maoris around Hokianga were already Methodists, and were openly hostile towards the recently arrived Catholics.

By 1840, the headquarters of the mission had changed to Kororareka. Additional Catholic Mission Stations were soon set up at Whangaroa, Kaipara, Tauranga, Akaroa, Matamata, Otaki, Rotorua, Rangiaowhia and Whakatane.

In 1840, Pompallier was present at the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, and it is thanks to him that the fourth article, involving freedom of religion, is present.

In 1841, a report showed 164 tribes as Catholic.

Many missionaries were opposed to the colonisation of New Zealand, because they wanted to avoid conflict between Maori and Europeans for land and resources, but were gradually convinced it would be for the best, and in turn convinced many Maori Chiefs to sign the Treaty of Waitangi between the British Crown and Maori.

The Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi was an agreement between the British and about 540 Maori chiefs, in which the Maori people gave their sovereignty to the British Crown. Today, it is seen as the founding document of New Zealand.

An Overview of the Treaty

Prior to 1840, the British Government was at first uninterested in annexing the country, but with New Zealand settlers becoming lawless and reports of the French planning to take control of the country, the British finally decided to act. Once the treaty had been authorised by British authorities, the English draft of the treaty was translated overnight by the missionary Henry Williams and his son, Edward, into Maori on the 4th of February 1840.

The treaty was then debated by about 500 Maori over the course of a day and a night, with Lieutenant-Governor William Hobson, who had been appointed the task of securing British control over New Zealand, stressing the benefits to the Maoris of British sovereignty. Once the chiefs were reassured that their status and authority would be strengthened, about 40 chiefs signed the treaty at Waitangi on the 6th of February 1840. After this, the document was taken all over the country, and about 500 more chiefs signed.

The English Version and the Maori Version are as follows:

The English Version of the Treaty

The actual draft for translation into Maori and dated 4th February 1840 was as follows: Her Majesty Victoria, Queen of England in Her gracious consideration of the chiefs and the people of New Zealand, and Her desire to preserve to them their lands and to maintain peace and order amongst them, has been pleased to appoint an officer to treat with them for the cession of the Sovereignty of their country and of the islands adjacent, to the Queen. Seeing that many of Her Majesty's subjects have already settled in the country and are constantly arriving, and it is desirable for their protection as well as the protection of the natives, to establish a government amongst them. Her Majesty has accordingly been pleased to appoint Mr. William Hobson, a captain in the Royal Navy to be Governor of such parts of New Zealand as may now or hereafter be ceded to Her Majesty and proposes to the chiefs of the Confederation of United Tribes of New Zealand and the other chiefs to agree to the following articles. Article first The chiefs of the Confederation of the United Tribes and the other chiefs who have not joined the confederation, cede to the Queen of England for ever the entire Sovereignty of their country. Article second The Queen of England confirms and guarantees to the chiefs and the tribes and to all the people of New Zealand, the possession of their lands, dwellings and all their property. But the chiefs of the Confederation of United Tribes and the other chiefs grant to the Queen, the exclusive rights of purchasing such lands as the proprietors thereof may be disposed to sell at such prices as may be agreed upon between them and the person appointed by the Queen to purchase from them. Article third In return for the cession of their Sovereignty to the Queen, the people of New Zealand shall be protected by the Queen of England and the rights and privileges of British subjects will be granted to them. Signed, William Hobson Consul and Lieut. Governor. Now we the chiefs of the Confederation of United Tribes of New Zealand assembled at Waitangi, and we the other tribes of New Zealand, having understood the meaning of these articles, accept them and agree to them all. In witness whereof our names or marks are affixed. Done at Waitangi on the 6th of February, 1840.

The Maori Version of the Treaty

KO WIKITORIA te Kuini o Ingarani i tana mahara atawai ki nga Rangatira me nga Hapu o Nu Tirani i tana hiahia hoki kia tohungia ki a ratou o ratou rangatiratanga me to ratou wenua, a kia mau tonu hoki te Rongo ki a ratou me te Atanoho hoki kua wakaaro ia he mea tika kia tukua mai tetahi Rangatira – hei kai wakarite ki nga Tangata maori o Nu Tirani – kia wakaaetia e nga Rangatira Maori te Kawanatanga o te Kuini ki nga wahikatoa o te wenua nei me nga motu – na te mea hoki he tokomaha ke nga tangata o tona Iwi Kua noho ki tenei wenua, a e haere mai nei.

Na ko te Kuini e hiahia ana kia wakaritea te Kawanatanga kia kaua ai nga kino e puta mai ki te tangata Maori ki te Pakeha e noho ture kore ana.

Na kua pai te Kuini kia tukua a hau a Wiremu Hopihona he Kapitana i te Roiara Nawi hei Kawana mo nga wahi katoa o Nu Tirani e tukua aianei amua atu ki te Kuini, e mea atu ana ia ki nga Rangatira o te wakaminenga o nga hapu o Nu Tirani me era Rangatira atu enei ture ka korerotia nei.

Ko te tuatahi Ko nga Rangatira o te wakaminenga me nga Rangatira katoa hoki ki hai i uru ki taua wakaminenga ka tuku rawa atu ki te Kuini o Ingarani ake tonu atu – te Kawanatanga katoa o o ratou wenua.

Ko te tuarua Ko te Kuini o Ingarani ka wakarite ka wakaae ki nga Rangitira ki nga hapu – ki nga tangata katoa o Nu Tirani te tino rangatiratanga o o ratou wenua o ratou kainga me o ratou taonga katoa. Otiia ko nga Rangatira o te wakaminenga me nga Rangatira katoa atu ka tuku ki te Kuini te hokonga o era wahi wenua e pai ai te tangata nona te Wenua – ki te ritenga o te utu e wakaritea ai e ratou ko te kai hoko e meatia nei e te Kuini hei kai hoko mona.

Ko te tuatoro Hei wakaritenga mai hoki tenei mo te wakaaetanga ki te Kawanatanga o te Kuini – Ka tiakina e te Kuini o Ingarani nga tangata maori katoa o Nu Tirani ka tukua ki a ratou nga tikanga katoa rite tahi ki ana mea ki nga tangata o Ingarani.

-William Hobson, Consul and Lieutenant-Governor.

Na ko matou ko nga Rangatira o te Wakaminenga o nga hapu o Nu Tirani ka huihui nei ki Waitangi ko matou hoki ko nga Rangatira o Nu Tirani ka kite nei i te ritenga o enei kupu, ka tangohia ka wakaaetia katoatia e matou, koia ka tohungia ai o matou ingoa o matou tohu.

Ka meatia tenei ki Waitangi i te ono o nga ra o Pepueri i te tau kotahi mano, e waru rau e wa te kau o to tatou Ariki.

A Literal Translation of the Maori Text

Here's Victoria, Queen of England, in her gracious remembrance towards the chiefs and tribes of New Zealand, and in her desire that the chieftainships and their lands should be secured to them and that obedience also should be held by them, and the peaceful state also; has considered it as a just thing, to send here some chief to be a person to arrange with the native men of New Zealand, that the Governorship of the Queen may be assented to by the native chiefs in all places of the land, and of the islands. Because too many together are the men of her tribe who have sat down in this land and are coming hither.

Now it is the Queen who desires that the Governorship may be arranged that evils may not come to the native men, to the white who dwells lawless. There! Now the Queen has been good that I should be sent, William Hobson, a captain of the Royal Navy, a Governor for all the places in New Zealand that are yielded now or hereafter to the Queen. She says to the Chiefs of the Assemblage (Confederation) of the tribes of New Zealand, and other chiefs besides, these laws which shall be spoken now.

Here's the first: Here's the chief of the Assemblage, and all the chiefs also who have not joined the Assemblage mentioned, cede to the utmost to the Queen of England for ever continually to the utmost the whole Governorship of their lands.

Here's the second: Here's the Queen of England arranges and confirms to the chiefs, to all the men of New Zealand the entire chieftainship of their lands, their villages, and all their property.

But here's the chiefs of the Assemblage, and all the chiefs besides, yield to the Queen the buying of those places of land where the man whose land it is shall be good to the arrangement of the payment which the buyer shall arrange to them, who is told by the Queen to buy for her.

Here's the third: This, too, is an arrangement in return for the assent of the Governorship of the Queen. The Queen of England will protect all the native men of New Zealand. She yields to them all the rights, one and the same as her doings to the men of England.

-William Hobson, Consul and Lieutenant-Governor.

Now here's we: Here's the chiefs of the Assemblage of the tribes of New Zealand who are congregated at Waitangi. Here's we too. Here's the chiefs of New Zealand, who see the meaning of these words, we accept, we entirely agree to all. Truly we do mark our names and marks.

This is done at Waitangi on the six of the days of February, in the year one thousand eight hundred and four tens of our Lord.

A Comparison of the English and Maori Versions

The final draft of the treaty was done by William Hobson and James Busby Although the English and Maori versions of the treaty are mostly the same, there are some subtle differences.

In the First Article, the English Version stated that the chiefs should give all rights and powers of sovereignty to the Queen. In the Maori Version it states that Maori give up government to the Queen. There is no direct translation for sovereignty in Maori, because the Maoris had individual tribes instead of an overall ruler.

In the Second Article, the English Version stated that the Crown had the sole right of purchase to Maori land. It is not certain if the Maori Version conveyed this message properly.

European Colonisation of New Zealand

Not long after New Zealand had been widely publicised about in Britain, attempts were made to colonise New Zealand. The British came to New Zealand in 1840.

The first attempt was in 1825, when the New Zealand Company was formed in England. The New Zealand Company believed that large profits could be made from New Zealand flax, kauri timber, whaling, sealing and the colonisation of New Zealand. The company unsuccessfully petitioned the British Government for a 31-year term of exclusive trade as well as command over a military force. Nevertheless, the company sent out two ships the next year, the Lambton and the Isabella, under the command of Captain James Herd, to look at trade prospects and potential settlements. The ships docked at present-day Wellington Harbour in September or October 1826, and Herd named it Lambton Harbour. Herd later explored the area, and identified a suitable point for a European settlement at the south-west end of the harbour. The ships then sailed north to look at trading prospects and supposedly purchased one million acres of land from Maori. However, the New Zealand Company decided not to pursue any ventures in New Zealand, as it had already spent ₤20,000 on it.

The first major passage to New Zealand was made available when a new New Zealand Company was set up in England. The company was not approved by the Colonial Office or the British Government, but the first ship, The Tory, departed England in May 1839. The New Zealand Company bought land cheaply off Maori in dishonest deals to gain as much land as possible before the British Government annexed New Zealand.

The New Zealand Company initially set up a settlement at Wellington, but soon set up settlements at Wanganui in 1840, at New Plymouth in 1841 and at Nelson in 1842. The company also sent surveyors down the South Island to look at further sites for settlement.

However, the Company soon got into financial difficulties. It had planned to buy land cheaply and sell it at high prices. It anticipated that a colony based on a higher land price would attract rich colonists. The profits from the sale of land were to be used to pay for free passage of the working-class colonists and for public works, churches and schools. For this scheme to work it was important to get the right proportion of labouring to propertied immigrants. In part, the failure of New Zealand Company plans was because this proportion was never achieved; there were always more labourers than employers.

The income from the sale of land to intending settlers never met expectations and came nowhere near meeting expenses. In 1844 the Company ceased active trading. It surrendered its charter in 1850. The British Government initially assumed responsibility for the New Zealand Company's debts, but gave them to the New Zealand government in 1854.

Over the next few years over 8,600 colonists arrived in New Zealand in over 57 ships. Europeans were a majority by 1859. By 1860, over 100,000 English, Scottish, Welsh and German immigrants had settled in New Zealand.

The New Zealand Wars

The New Zealand Wars were a series of conflicts- mainly in the North Island between the native Maori, British troops and occasionally settlers.

The causes of the wars are believed to be the sudden influx of European settlers to New Zealand (far more arrived than the Maoris anticipated), and the struggle for control of the land that followed. Also, many chiefs felt that the British were not holding up their end of the bargain with the Treaty of Waitangi.

There were at least nine distinct wars in the New Zealand Wars. They were:

The Wairau Confrontation - 1843

In the first engagement of the New Zealand Wars, 49 armed settlers from Nelson tried to enforce a disputed land sale with Maori from the Ngati Toa tribe. The land on the Wairau Plains had supposedly been bought earlier by The New Zealand Company, but the local Maori disputed that claim.

The rights to the land were under investigation at the time by Land Claims Commissioner, William Spain, but after Maori burned a surveyor's hut on the Wairau Plains to the ground, some Nelson settlers had decided to take things into their own hands.

The initial skirmish was unsuccessful, with the Maori refusing to surrender the land. Fifteen Maori and settlers were killed, eleven Europeans were captured and around thirty-nine settlers escaped the scene.

The new Governor, Robert FitzRoy, considered a major invasion on the Ngati Toa tribe, but eventually decided against it because the settlers had been wrong in taking matters into their own hands.

The Northern War - 1845-46

The Northern War involved the British Army's pursuit of Hone Heke and Kawhiti of the Nga Puhi tribe, after Heke attempted to cut the British flag pole down a fourth and final time, to show the British empire as weak. This attack resulted in the burning, destruction and looting of New Zealands capital Kororareka after Kawiti and Heke attacked the British in March 1845.

Three of the major engagements in the Northern War were fought at Puketutu, Ohaeawai and Ruapekapeka.

The Wellington-Hutt War - 1846

Continued confrontations over disputed land sales in the Hutt Valley were the cause of the Wellington-Hutt War, which was fought between the Ngati Toa tribe, settlers and the British Army. The Ngati Toa tribe eventually fled north to refuge.

Wanganui War - 1847-48

Disputed land sales led to conflict around Wanganui. Wanganui itself was attacked by Topine Te Mamaku.

North Taranaki War - 1860-61

War broke out in North Taranaki in March 1860 over a block of land which a Te Atiawa Chief wanted to sell to the Crown, but many members of the tribe didn't want to give up.

The Maori opposed to the sale were led by Wiremu Kingi. The Governor soon sent out surveyors to the block of land, but the members of the Te Atiawa tribe opposed to the sale obstructed them, and built a Pa inside the south-east corner of the block of land.

On the 17th of March 1860, the British Army marched out from New Plymouth and opened fire on the Pa.

Further engagements were fought at Puketekauere, Mahoetahi, No 3 Redoubt and Te Arei.

The British Army eventually prevailed over the Maori, and a truce was signed at Te Arei Pa in 1861.

Invasion of the Waikato - 1863-64

One of the major wars of the New Zealand Wars, the Invasion of the Waikato was a massive British Army invasion of the Maori King's home district, the Waikato. The British Army ultimately defeated Waikato and its allies at Orakau in 1864. The Maori King fled, and took refuge amongst the Ngati Maniapoto tribe.

Tauranga - 1864

Major battles were fought between the Ngai Te Rangi tribe, the British Army and settlers at Gate Pa and Te Ranga.

Central-South Taranaki War - 1863-69

The Ngati Ruanui tribe, which had been helping other tribes in the North Taranaki War, returned to Southern Taranaki after the war, and attacked Tataraimaka in 1863. The British Army was sent into the area to control the Maori. The British Army was eventually replaced by the New Zealand Armed Constabulary, so the British Army could return home to England.

East Coast War - 1868-72

Te Kooti, of the Rongowhakaata tribe, escaped from his imprisonment on the Chatham Islands, and with his followers, was chased across the North Island. He eventually found refuge in the King Country.

Railways Introduced to New Zealand

Railways were initially constructed by provincial governments looking for a mode of efficient transportation.

The first railway in New Zealand was constructed by the Canterbury Provincial Government in 1863. It was built to a broad gauge of 5 feet 3 inches (1600 mm), to suit rolling stock imported from Victoria, Australia. Its primary purpose was to service ships docked at the Ferrymead wharf.

On the 5th of February 1867, the Southland Provincial Government opened a branch railway from Invercargill to Bluff. This railway was built to the international standard gauge of 4 ft 8½ inches (1,435 mm). At this stage, the Central Government set the national gauge at 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm).

A narrow-gauge line was opened on 1 January 1873, in the Otago Province, and Auckland's first railway, between Auckland and Onehunga, opened in 1873.

After the abolition of provincial governments in 1876, the Central Government took over the building of railways in New Zealand.

The Colonial Government

After New Zealand was annexed by Britain, it was initially set up as a dependency of New South Wales. However, by 1841, New Zealand was made a colony in its own right. As a colony, it inherited political practices and institutions of government from the United Kingdom.

The United Kingdom Government started the first New Zealand Government by appointing governors, being advised by appointed executive and legislative councils.

In 1852, the British Parliament passed the New Zealand Constitution Act, which provided for the elected House of Representatives and Legislative Council. The General Assembly (the House and Council combined) first met in 1854.

New Zealand was effectively self-governing in all domestic matters except 'native policy' by 1856. Control over native policy was passed to the Colonial Government in the mid-1860s.

The first capital of the country was Russell, located in the Bay of Islands, declared by Governor Hobson after New Zealand was formally annexed. In September 1840, Hobson changed the capital to the shores of the Waitematā Harbour where Auckland was founded. The seat of Government was centralised in Wellington by 1865.

Provincial Governments in New Zealand

From 1841 until 1876, provinces had their own provincial governments. Originally, there were only three provinces, set up by the Royal Charter:

- New Ulster (North Island north of Patea River)

- New Munster (North Island south of Patea River, plus the South Island)

- New Leinster (Stewart Island)

In 1846, the provinces were reformed. The New Leinster province was removed, and the two remaining provinces were enlarged and separated from the Colonial Government. The reformed provinces were:

- New Ulster (All of North Island)

- New Munster (The South Island plus Stewart Island)

The provinces were reformed yet again by the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852. In this constitution, the old provinces of New Ulster and New Munster were abolished and six new provinces were set up:

- Auckland

- New Plymouth

- Wellington

- Nelson

- Canterbury

- Otago

Each province had its own legislature that elected its own Speaker and Superintendent. Any male 21 years or older that owned freehold property worth £50 a year could vote. Elections were held every four years.

Four new provinces were introduced between November 1858 and December 1873. Hawkes Bay broke away from Wellington, Marlborough from Nelson, Westland from Canterbury, and Southland from Otago.

Not long after they had begun, provincial governments were a matter for political debate in the General Assembly. Eventually, under the premiership of Harry Atkinson, the Colonial Government passed the Abolition of Provinces Act 1876, which wiped out the provincial governments, replacing them with regions. Provinces finally ceased to exist on the 1st of January 1877.

PART 3: NEW ZEALAND IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

The Dawn of the Twentieth Century

Major Events from 1900 to 1914

1900

Second Boer War

By the beginning of the twentieth century, New Zealand was already engaged in its first overseas military campaign, the Second Boer War, in which it helped the British Empire fight against the two independent Boer republics, the Orange Free State and the South African Republic (Transvaal Republic). There were two notable campaigns in 1900:

- 15th of January 1900: The New Zealand Mounted Rifles defeated a Boer assault at Slingersfontein, South Africa.

- 15th of February 1900: New Zealand troops were part of the relief of Kimberley.

1901

The Cook Islands and other Pacific Islands were annexed by New Zealand.

1903

Richard Pearse Carries out what is Believed to be the First Manned Heavier-than-air Flight

Richard Pearse, a New Zealand farmer and inventor, was a pioneer in aviation. On the 31st of March 1903, Richard Pearse achieved a semi-controlled flight near Timaru in his home-built plane, approximately nine months before the Wright brothers did.

Pearse built the plane in a workshop on his farm, out of bamboo wire and canvas. When he tested the plane on the 31st of March 1903, it managed to fly several hundred metres before crashing into a hedge. The flight was hardly controlled, however.

Although there were a number of witnesses to this event, Richard Pearse was not very eager to have his achievement widely publicised, or have his planes put into mass production, so his flight is not nearly as well known as the Wright Brothers' flight.

1907

- Fire destroyed Parliament buildings.

- Dominion of New Zealand was declared after New Zealand decided not to join the Australian Federation.

1908

- North Island Main Trunk Railway Line opened.

- New Zealand's population reached one million.

New Zealand's Involvement in World War I

After the United Kingdom declared war on Germany in 1914, New Zealand followed without second thoughts. New Zealand only had a small population of just over one million at the time, and was fairly isolated from the rest of the world, but due to New Zealand's strong ties to Britain it offered its services to the Allied Forces.

New Zealand's first act in the war was to seize German Samoa. New Zealand sent 1,413 men to conduct this action and took control of the territory without much resistance. It was the first German territory to be occupied in the name of King George V in the war.

On the 25th of April 1915, New Zealand sent troops to Gallipoli under the command of British General Alexander Godly, along with Australian soldiers, to help seize Constantinople. Due to a navigational error, however, they landed at the wrong point, and the steep cliffs in the cove they had disembarked at offered the Turkish defenders a significant vantage point. Advancement of the New Zealand-Australian forces was impossible. New Zealand suffered casualties of 2,721 dead and 4,852 wounded in the cove, and eventually it was decided to evacuate. The battle was the first great conflict of New Zealand, and the loss was felt greatly in New Zealand.

New Zealand forces also helped on the Western Front in France, in which, by the time they were relieved, had advanced three kilometres and taken eight kilometres of enemy front line. 1560 New Zealand men were killed, and 7048 were wounded.

Casualties

Out of the 103,000 men recruited, 16,697 New Zealanders serving in the war had been killed and 41,317 had been wounded; a 58 percent casualty rate. This was one of the highest rates per capita of any country involved in the war. Approximately a further thousand men died after the war, as a result of injuries suffered.

New Zealand in the Great Depression

As in many other countries, New Zealand National income fell by 40 per cent in three years. Exports were greatly affected, falling by 45 per cent in just two years.

The value of wool declined by 60 per cent from 1929 to 1932, but the value of meat wasn't so badly affected. Dairy farmers increased production of butter and cheese to try and meet the increasing problems, but failed in doing so.

In 1935, the Labour Party became the new government, seeking to promote economic stability. In this, they achieved much, developing social services, state housing, bringing wages back up, and restoring New Zealand to a sense of normality.

New Zealand in World War II

New Zealand declared war on Germany at 9.30 pm on the 3rd of September 1939, thus entering World War II. New Zealand assisted Britain, as New Zealanders still felt loyal to their 'mother country'.

New Zealand provided men for service in the British Royal Air Force and Royal Navy. The New Zealand Royal Navy was placed at Britain's disposal, and new bombers waiting in the United Kingdom to be shipped to New Zealand were made available to the Royal Air Force.

The New Zealand Army contributed the New Zealand 2nd Division to the war.

In April 1941, New Zealand's 2nd Division was deployed to Greece, to help the British and Australians defend the country from the invading Italians. The Germans soon joined in the fight, overwhelming the British and Commonwealth forces. Due to this factor, the British and Commonwealth forces had to retreat to Crete and Egypt by the 6th of April. The last New Zealand troops had evacuated Greece by the 25th of April, having sustained losses of 291 men killed, 387 seriously wounded, and 1,826 men captured in this campaign.

Since most New Zealand 2nd Division troops had evacuated to Crete, they were very much involved in the defence of Crete against German soldiers in May 1941. By the end of the month, however, German soldiers had once again overwhelmed British and Commonwealth forces, and it was decided to evacuate to Alexandria by June. In battle, 671 New Zealanders were killed, 967 wounded and 2,180 captured.

On the 18th of November 1941, the New Zealand 2nd Division took part in the North Africa Operation Crusader campaign. Merged into the British Eighth Army, New Zealand troops crossed the Libyan frontier into Cyrenaica. Operation Crusader was an overall success for the British, and New Zealand troops withdrew to Syria to recover. The Operation Crusader campaign was the most costly the New Zealand 2nd Division fought in the Second World War, with 879 men killed, and 1700 wounded.

The New Zealand 3rd Division, which was active after December 1941, supplemented existing garrison troops in the South Pacific. However, New Zealand troops were eventually replaced by American soldiers, freeing up the New Zealand 3rd Division for service within the New Zealand 2nd Division, which was in Italy.

New Zealand participated in the war until its end in 1945.

Casualties

In total, around 140,000 men served overseas for the Allied war effort. The war had a high cost on the country, with 11,625 New Zealand men killed, a ratio of 6684 dead per million in the population which was the highest rate in the Commonwealth.

Major Events in the Mid to Late Twentieth Century

1947 - Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1947

New Zealand gained total independence from Britain, through the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act of 1947. New Zealand today is an independent member of the British Commonwealth.

The British monarch is the constitutional head of state, although plays no part in the running of New Zealand. The Governor General, who is generally a New Zealander, represents the monarch in New Zealand's Parliament.

1953 - Tangiwai Rail Disaster

At 10:21pm on Christmas Eve 1953, a lahar from a nearby volcano knocked out the rail bridge over the Whangaehu River at Tangiwai, just before the Wellington–Auckland night express train was due to cross it. The train plunged into the flooded river at high speed, killing 151 of the 285 passengers on board. At the time it was the eighth biggest rail disaster the world had seen. The whole nation, with a population of just over 2 million were stunned. For his actions in attempting to stop the train by running along the line waving a torch, Arthur Cyril Ellis was awarded the George Medal, New Zealand's highest civilian award.

1967 - Introduction of a Decimal Currency

A decimal currency was introduced to New Zealand, replacing the old system of pounds, shillings and pence.

The first decimal coins were introduced on the 10th of July 1967.

1981 - Springboks Rugby Tour

With the controversial tour of New Zealand by the South African Springboks rugby team, many New Zealanders were unhappy because the South Africans were still involved in apartheid. The tour was approved by the New Zealand Rugby Football Union, and the Government didn't intervene because the Prime Minister, Robert Muldoon, had a policy that politics shouldn't interfere with sport.

The protests against the tour were some of the most violent in New Zealand history. Protesters filled the streets outside stadiums where games were being played, and successfully invaded the pitch at some games, stopping gameplay.

After the tour, the popularity of Rugby Union in New Zealand decreased until the All Blacks won the Rugby World Cup in 1987.

1985 - Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior

In 1985, The New Zealand Government funded the voyages of the Greenpeace 'Rainbow Warrior'. These voyages were designed to protest and prevent the French nuclear testing in the Mururoa Atoll. The French Government, in conjunction with the w:DGSE, planned to bomb the civilian vessel. Today, this action would be condemned as a Terrorist Attack or State Sponsored Terrorism. On 10th of July, 1985, French agents, using scuba equipment, began to plant the limpet mines on the hull of the civilian craft. The first bomb went off at 23:48. The crew of the Rainbow Warrior initially evacuated, but some of the crew returned to investigate the damage. Fernando Pereira, a photographer, was collecting photographic equipment at his cabin. Then, at around 23:51, the second bomb went off. The rapid flooding killed Fernando Pereira.

Initially, the French Government denied any involvement of the bombing. The French statement from the New Zealand embassy was "the French Government does not deal with its opponents in such ways". When tried, two of the French agents, Dominique Prieur and Alain Marfart, pleaded guilty of manslaughter and wilful damage. Their sentences were 10 years and 7 years respectively, but were transferred to the Hao Atoll, a French Base, to receive a lesser sentence.

Then they were released within less than two years.

1987 - Māori Language Act

The Maori language Act, signed in 1987, gave official legal status to to the Maori language (Te Reo Maori). This was in response to a revival in Maori culture in New Zealand, and the Waitangi Tribunal, which was called forth to make amends to the supposed breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi. This Tribunal found breaches on both the Crown and Maori sides, and large portions of land was returned to the various Maori iwi. This act also gave the privilege to New Zealand citizens to use Te Reo Maori in court.

Famous New Zealanders

Edmund Hillary

On the 29th of May 1953, New Zealander Edmund Hillary became the first person to reach the summit of Mount Everest with Nepalese climber Tenzing Norgay (the summit at the time was 29,028 feet above sea level). He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II on his return. Sir Edmund Hillary was famous after news spread he had reached the summit, but he didn't finish at Mount Everest. He led the New Zealand section of the Trans-Antarctic expedition from 1955 to 1958.

In the 1960s, he returned to Nepal to build clinics, hospitals and schools for the Nepalese people. He also convinced their government to pass laws to protect their forests and the area around Mount Everest.

In the 1970s, several books were published by Hillary about his journey up Mount Everest.

Edmund Hillary is one of the most famous New Zealanders, and appears on the New Zealand five dollar note.

He died on the 11th of January 2008.

Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford was a nuclear physicist who became known as the 'father' of nuclear physics. He pioneered the Bohr model of the atom through his discovery of Rutherford scattering off the atomic nucleus with his Geiger-Marsden experiment (gold foil experiment).

He was born in Brightwater, New Zealand, but lived in England for a number of years.

He received the Commonwealth Order of Merit, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1908, and was a member of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom and the Royal Society.

Rutherford appears on the New Zealand one hundred dollar note.

Politics in the Twentieth Century

Political Parties and Key Policies of the Twentieth Century

At the turn of the century, the Liberals, New Zealand's first modern political party, were in power as the Government. The Liberals created a 'family farm' economy, by subdividing large estates and buying more Maori land in the North Island. New Zealand gained strong economic ties with Britain, exporting farm produce and other goods. Under Liberal, New Zealand started to form its own identity, and due to this, New Zealand declined to join the Australian Federation of 1901.

The Liberals were defeated in the 1912 election by the Reform Party, and never fully recovered. William Massey, the leader of the Reform Party, had promised state leaseholders they could freehold their land, which proved to be a good promise in winning the election. Under the Reform Party, New Zealand entered World War I, aiding Britain.

New Zealand had prosperous years at the end of the 1920s, and so was hit hard by the Great Depression of the 1930s. The Conservative coalition government failed to get New Zealand out of the Depression, which led to the rise of the Labour Party in 1935.

Under Labour, New Zealand's economy slowly recovered. The Reserve Bank was taken over by the state in 1936, spending on public works increased, and the State Housing Programme began. The Social Security Act 1938 increased the state of welfare dramatically.

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the New Zealand Government again chose to support Britain with troops. New Zealand also chose to fight in Korea in the early 1950s.

In 1945, Peter Fraser played a significant role in the conference that set up the United Nations, but the Labour Government was losing support. In 1949, the National Party became the Government of New Zealand. In the 1960s, the National Government sent troops to Vietnam to keep on side with the United States, despite protests, but this didn't hinder New Zealand's support of the National Party, and National ruled New Zealand until 1984 with only two exceptions.

New Zealand's culture remained based on Britain's through the 1960s, and the economy was still mainly made up of exporting farm produce to Britain. However, when Britain joined the European Economic Community in 1973, New Zealand no longer had an assured market for farm products.

After the second oil shock of 1978, the National Government tried to fix the problem with new industrial and energy initiatives and farm subsidies. The economy faltered in the 1980s when the fall of oil prices made these schemes unsound. Inflation and unemployment went up as a result.

The National Government of 1990-99 passed the controversial Employment Contracts Act which opened up the labour market, but diminished the power of trade unions.

In 1996, a new voting system was introduced, Mixed Member Proportional Representation, which allowed minority or coalition Governments to become the norm, but the National and Labour parties still remained dominant.

Prime Ministers of the Twentieth Century

| Name | Term in Office | Party |

|---|---|---|

| Joseph Ward | 6 August 1906 - 28 March 1912 | Liberal |

| Thomas Mackenzie | 28 March 1912 - 10 July 1912 | Liberal |

| William Massey | 10 July 1912 - 10 May 1925 | Reform |

| Francis Bell | 10 May 1925 - 30 May 1925 | Reform |

| Gordon Coates | 30 May 1925 - 10 December 1928 | Reform |

| Joseph Ward (2nd time) | 10 December 1928 - 28 May 1930 | United (Liberal) |

| George Forbes | 28 May 1930 - 6 December 1935 | United (Liberal) |

| Michael Joseph Savage | 6 December 1935 - 27 March 1940 | Labour |

| Peter Fraser | 27 March 1940 - 13 December 1949 | Labour |

| Sidney Holland | 13 December 1949 - 20 September 1957 | National |

| Keith Holyoake | 20 September 1957 - 12 December 1957 | National |

| Walter Nash | 12 December 1957 - 12 December 1960 | Labour |

| Keith Holyoake (2nd time) | 12 December 1960 - 7 February 1972 | National |

| Jack Marshall | 7 February 1972 - 8 December 1972 | National |

| Norman Kirk | 8 December 1972 - 31 August 1974 | Labour |

| Hugh Watt (Acting) | 31 August 1974 - 6 September 1974 | Labour |

| Bill Rowling | 6 September 1974 - 12 December 1975 | Labour |

| Robert Muldoon | 12 December 1975 - 26 July 1984 | National |

| David Lange | 26 July 1984 - 8 August 1989 | Labour |

| Geoffrey Palmer | 8 August 1989 - 4 September 1990 | Labour |

| Mike Moore | 4 September 1990 - 2 November 1990 | Labour |

| Jim Bolger | 2 November 1990 - 8 December 1997 | National |

| Jenny Shipley | 8 December 1997 - 5 December 1999 | National |

PART 4: NEW ZEALAND'S RECENT HISTORY

New Zealand's Recent History

Major Events in the Twenty First Century - 2000-2007

2003

The population of New Zealand reached four million.

2004

The Foreshore and Seabed Controversy

The foreshore and seabed controversy was under heavy debate in 2004. The foreshore and seabed debate involved the Maori wanting ownership of New Zealand beaches, as they saw it a customary right. This claim was based around the fact that Maori used to 'own' the beaches before Europeans came to New Zealand, and the Treaty of Waitangi stated that Maori could keep their lands and possessions.

The New Zealand public were surprised and shocked by the claim to the beaches. The Prime Minister at the time, Helen Clark, said that the Government would be passing law to ensure that beaches remained in public hands. However, the law incorporated Maori being consulted over foreshore and seabed matters. Due to this, the Labour Party was heavily attacked by National Party leader, Don Brash, who said the Government showed favouritism towards Maoris. Soon afterwards National was ahead of Labour in an opinion poll.

On the 18th of November 2004, the Labour Government passed the Foreshore and Seabed Bill and it became law. The Act made the foreshore and seabed property of the Crown. However, the Act was still subject to dispute, with some calling for modifications to the law.

The Maori Party Formed

The Maori Party was launched on the 7th of July 2004. It was formed around a former Labour Party Cabinet Minister, Tariana Turia, and as its name suggests, it is based on the indigenous Maori population. The foreshore and seabed controversy was one of the main reasons for setting up the party.

The Maori Party contested the 2005 general elections, and won four of the seven Maori seats and 2.12% of the party vote.

2007

Anti-smacking Bill Passed as Law

The Crimes (Substituted Section 59) Amendment Act 2007, commonly known as the anti-smacking Bill, was a highly controversial Bill introduced by Green Party MP Sue Bradford, which amended Section 59 of the Crimes Act. The Bill removed legal defence of 'reasonable force' for parents prosecuted of assaulting their children.

There was large-scale public opposition to the Bill. In opinion polls, there was overwhelming public opposition to the Bill. Despite this, the Bill was passed on the 16th of May 2007, with a large majority of 113 votes against 8.

New Zealand Prime Ministers at the Start of the Twenty First Century (1999-2008)

Helen Clark

Helen Clark (born on the 26th of February 1950) was the Prime Minister of New Zealand at the turn of the Twenty First Century, entering the role after the 1999 elections and serving until Labour's defeat in the 2008 elections.

Clark was the second female Prime Minister of New Zealand, serving three terms as Prime Minister, and being the leader of the Labour Party from 1993.

Clark's Government brought in significant changes to New Zealand's welfare system, most notably the Working for Families package. Her Government also changed the industrial-relations law, and raised the minimum wage six times. Other changes included the abolition of interest on student loans (after the 2005 election), and the introduction of 14 weeks paid parental leave. Helen Clark's Government also supported some highly controversial laws such as legal provision for civil-unions. Laws such as these somewhat shook the faith that the New Zealand public had in the Government.

Under the Helen Clark Government, New Zealand maintained a nuclear-free policy, thought to be at the cost of a free trade agreement with the United States of America. Clark and the Labour Party also refused to assist the United States in the Iraq invasion.

In March 2003, referring to the U.S. led coalition's actions in the Iraq War, Clark told the newspaper Sunday Star Times; "I don't think that September 11 under a Gore presidency would have had this consequence for Iraq." She subsequently sent a letter to Washington apologising for any offence that her comment may have caused.

John Key

John Key (born on the 9th of August 1961) was elected as the 38th Prime Minister of New Zealand on the 8th of November 2008, as the leader of the National Government.

National formed a coalition with the ACT party, Maori Party and United Future to make up the Government. The Labour Party (led by Phil Goff), the Green Party and the Progressives made the new Opposition.

John Key was the first male Prime Minister of New Zealand in more than a decade, succeeding Jenny Shipley (1997-1999) and Helen Clark (1999-2008).

The New Zealand Government at the Turn of the Twenty First Century

New Zealand, at the turn of the Twenty First Century, was run by the Labour Party, under the leadership of Helen Clark - the electoral system being MMP (Mixed Member Proportional Representation), which was implemented in 1996.

The MMP system allows for two votes on election day: a 'Party Vote' (the vote given to the party the voter wants represented in Parliament), and the 'Electorate Vote' (the vote given to the MP the voter wants to represent their electorate in Parliament). Due to the nature of this system, it is unlikely that a party will be able to govern without the support of minor parties. When parties make an agreement to form a Government it is called a 'coalition'. For example, following the 2005 election, the formal coalition comprised of the Labour Party (the major party, receiving a majority of votes) and the Progressive Party (the minor party), but the New Zealand First and United Future parties also provided confidence and supply to Labour in return for their leaders being Ministers outside of cabinet. The rest of the parties made up the Opposition: after the 2005 election, this was the National Party, the ACT Party and the Maori Party.

In 2008, the National Party received the majority of votes in the election, and it made a coalition agreement with the ACT Party, Maori Party, and United Future, which collectively made up enough seats in Parliament to have an overall majority. Therefore, a National-led coalition became the new Government. This made the Labour Party, Green Party, and the Progressive Party the Opposition.

This table shows how Parliament was made up after the 2005 election. It also gives a background to some of the main parties in New Zealand politics, and who they aim to represent in Parliament.

| Party | Number of Seats in Parliament (2005-2008) | Leader(s)

(2005-2008) |

Description of Party |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labour Party | 49 | Helen Clark | The Labour Party is a socially progressive party, formed in July 1916. After the 2005 election it was the largest party in Parliament (by one seat) and was the New Zealand Government up until the 2008 elections. Its leader, Helen Clark, was the Prime Minister of New Zealand, having been appointed in 1999, and winning the two successive elections. |

| National Party | 48 | John Key | The National Party is a socially conservative party, formed in May 1936. It was the second largest party in Parliament, and is traditionally Labour's main opponent. In the past it has been strongly supported by farmers.

After a record loss to Labour in the 2002 election, National made a remarkable recovery in the 2005 election under the leadership of Don Brash, only losing the election by 2 percent (one seat). |

| New Zealand First | 7 | Winston Peters | New Zealand First is a centrist, populist, and nationalist party. New Zealand First took a strong stand on reducing immigration, cutting back on Treaty of Waitangi payments, increasing sentences for crime, and buying back former state assets. The party had a confidence and supply agreement with the Government, resulting in the party's leader, Winston Peters, becoming the Foreign Affairs Minister. After the 2008 election, the party lost all seats in Parliament. |

| Green Party | 6 | Jeanette Fitzsimons and Russel Norman | The Green Party is New Zealand's major environmentalist party. It promotes views on carbon emissions and other major environmental topics, and typically does reasonably well in elections. |

| Māori Party | 4 | Tariana Turia and Pita Sharples | The Maori party is based around the Maori population in New Zealand. It was formed in 2004 around Tariana Turia, a former minister of the Labour Party. It promotes Maori rights in Parliament. |

| United Future | 2 | Peter Dunne | United Future is a 'common sense' party based around family values. Although United Future had a strong Christian background, it does not promote its Christian side any longer. The party had a confidence and supply agreement with the Labour Government, but after the 2008 election switched to being part of the National coalition. |

| ACT | 2 | Rodney Hide | The ACT Party is a classically liberal party. It promotes lower taxation, reducing government expenditure, and increasing punishments for crime. |

| Progressive Party | 1 | Jim Anderton | The Progressive Party had one elected MP after the 2005 election, the party's leader, Jim Anderton, and has had a recent focus on employment and regional development. It was part of the coalition with the Labour Government. |

END NOTES

Bibliography

Books

- Bateman New Zealand Encyclopedia

Websites

- http://history-nz.org

- http://www.nzhistory.net.nz

- The 1966 Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

- Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Authors

- Original Author: Helpfulstuffnz

- Additions by: Ferrum Dominus

| This page or section is an undeveloped draft or outline. You can help to develop the work, or you can ask for assistance in the project room. |

GNU Free Documentation License

As of July 15, 2009 Wikibooks has moved to a dual-licensing system that supersedes the previous GFDL only licensing. In short, this means that text licensed under the GFDL only can no longer be imported to Wikibooks, retroactive to 1 November 2008. Additionally, Wikibooks text might or might not now be exportable under the GFDL depending on whether or not any content was added and not removed since July 15. |

Version 1.3, 3 November 2008 Copyright (C) 2000, 2001, 2002, 2007, 2008 Free Software Foundation, Inc. <http://fsf.org/>

Everyone is permitted to copy and distribute verbatim copies of this license document, but changing it is not allowed.

0. PREAMBLE

The purpose of this License is to make a manual, textbook, or other functional and useful document "free" in the sense of freedom: to assure everyone the effective freedom to copy and redistribute it, with or without modifying it, either commercially or noncommercially. Secondarily, this License preserves for the author and publisher a way to get credit for their work, while not being considered responsible for modifications made by others.

This License is a kind of "copyleft", which means that derivative works of the document must themselves be free in the same sense. It complements the GNU General Public License, which is a copyleft license designed for free software.

We have designed this License in order to use it for manuals for free software, because free software needs free documentation: a free program should come with manuals providing the same freedoms that the software does. But this License is not limited to software manuals; it can be used for any textual work, regardless of subject matter or whether it is published as a printed book. We recommend this License principally for works whose purpose is instruction or reference.

1. APPLICABILITY AND DEFINITIONS

This License applies to any manual or other work, in any medium, that contains a notice placed by the copyright holder saying it can be distributed under the terms of this License. Such a notice grants a world-wide, royalty-free license, unlimited in duration, to use that work under the conditions stated herein. The "Document", below, refers to any such manual or work. Any member of the public is a licensee, and is addressed as "you". You accept the license if you copy, modify or distribute the work in a way requiring permission under copyright law.

A "Modified Version" of the Document means any work containing the Document or a portion of it, either copied verbatim, or with modifications and/or translated into another language.

A "Secondary Section" is a named appendix or a front-matter section of the Document that deals exclusively with the relationship of the publishers or authors of the Document to the Document's overall subject (or to related matters) and contains nothing that could fall directly within that overall subject. (Thus, if the Document is in part a textbook of mathematics, a Secondary Section may not explain any mathematics.) The relationship could be a matter of historical connection with the subject or with related matters, or of legal, commercial, philosophical, ethical or political position regarding them.

The "Invariant Sections" are certain Secondary Sections whose titles are designated, as being those of Invariant Sections, in the notice that says that the Document is released under this License. If a section does not fit the above definition of Secondary then it is not allowed to be designated as Invariant. The Document may contain zero Invariant Sections. If the Document does not identify any Invariant Sections then there are none.

The "Cover Texts" are certain short passages of text that are listed, as Front-Cover Texts or Back-Cover Texts, in the notice that says that the Document is released under this License. A Front-Cover Text may be at most 5 words, and a Back-Cover Text may be at most 25 words.

A "Transparent" copy of the Document means a machine-readable copy, represented in a format whose specification is available to the general public, that is suitable for revising the document straightforwardly with generic text editors or (for images composed of pixels) generic paint programs or (for drawings) some widely available drawing editor, and that is suitable for input to text formatters or for automatic translation to a variety of formats suitable for input to text formatters. A copy made in an otherwise Transparent file format whose markup, or absence of markup, has been arranged to thwart or discourage subsequent modification by readers is not Transparent. An image format is not Transparent if used for any substantial amount of text. A copy that is not "Transparent" is called "Opaque".

Examples of suitable formats for Transparent copies include plain ASCII without markup, Texinfo input format, LaTeX input format, SGML or XML using a publicly available DTD, and standard-conforming simple HTML, PostScript or PDF designed for human modification. Examples of transparent image formats include PNG, XCF and JPG. Opaque formats include proprietary formats that can be read and edited only by proprietary word processors, SGML or XML for which the DTD and/or processing tools are not generally available, and the machine-generated HTML, PostScript or PDF produced by some word processors for output purposes only.

The "Title Page" means, for a printed book, the title page itself, plus such following pages as are needed to hold, legibly, the material this License requires to appear in the title page. For works in formats which do not have any title page as such, "Title Page" means the text near the most prominent appearance of the work's title, preceding the beginning of the body of the text.

The "publisher" means any person or entity that distributes copies of the Document to the public.

A section "Entitled XYZ" means a named subunit of the Document whose title either is precisely XYZ or contains XYZ in parentheses following text that translates XYZ in another language. (Here XYZ stands for a specific section name mentioned below, such as "Acknowledgements", "Dedications", "Endorsements", or "History".) To "Preserve the Title" of such a section when you modify the Document means that it remains a section "Entitled XYZ" according to this definition.

The Document may include Warranty Disclaimers next to the notice which states that this License applies to the Document. These Warranty Disclaimers are considered to be included by reference in this License, but only as regards disclaiming warranties: any other implication that these Warranty Disclaimers may have is void and has no effect on the meaning of this License.

2. VERBATIM COPYING

You may copy and distribute the Document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this License, the copyright notices, and the license notice saying this License applies to the Document are reproduced in all copies, and that you add no other conditions whatsoever to those of this License. You may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the reading or further copying of the copies you make or distribute. However, you may accept compensation in exchange for copies. If you distribute a large enough number of copies you must also follow the conditions in section 3.

You may also lend copies, under the same conditions stated above, and you may publicly display copies.

3. COPYING IN QUANTITY

If you publish printed copies (or copies in media that commonly have printed covers) of the Document, numbering more than 100, and the Document's license notice requires Cover Texts, you must enclose the copies in covers that carry, clearly and legibly, all these Cover Texts: Front-Cover Texts on the front cover, and Back-Cover Texts on the back cover. Both covers must also clearly and legibly identify you as the publisher of these copies. The front cover must present the full title with all words of the title equally prominent and visible. You may add other material on the covers in addition. Copying with changes limited to the covers, as long as they preserve the title of the Document and satisfy these conditions, can be treated as verbatim copying in other respects.

If the required texts for either cover are too voluminous to fit legibly, you should put the first ones listed (as many as fit reasonably) on the actual cover, and continue the rest onto adjacent pages.

If you publish or distribute Opaque copies of the Document numbering more than 100, you must either include a machine-readable Transparent copy along with each Opaque copy, or state in or with each Opaque copy a computer-network location from which the general network-using public has access to download using public-standard network protocols a complete Transparent copy of the Document, free of added material. If you use the latter option, you must take reasonably prudent steps, when you begin distribution of Opaque copies in quantity, to ensure that this Transparent copy will remain thus accessible at the stated location until at least one year after the last time you distribute an Opaque copy (directly or through your agents or retailers) of that edition to the public.

It is requested, but not required, that you contact the authors of the Document well before redistributing any large number of copies, to give them a chance to provide you with an updated version of the Document.

4. MODIFICATIONS

You may copy and distribute a Modified Version of the Document under the conditions of sections 2 and 3 above, provided that you release the Modified Version under precisely this License, with the Modified Version filling the role of the Document, thus licensing distribution and modification of the Modified Version to whoever possesses a copy of it. In addition, you must do these things in the Modified Version:

- Use in the Title Page (and on the covers, if any) a title distinct from that of the Document, and from those of previous versions (which should, if there were any, be listed in the History section of the Document). You may use the same title as a previous version if the original publisher of that version gives permission.

- List on the Title Page, as authors, one or more persons or entities responsible for authorship of the modifications in the Modified Version, together with at least five of the principal authors of the Document (all of its principal authors, if it has fewer than five), unless they release you from this requirement.

- State on the Title page the name of the publisher of the Modified Version, as the publisher.

- Preserve all the copyright notices of the Document.

- Add an appropriate copyright notice for your modifications adjacent to the other copyright notices.

- Include, immediately after the copyright notices, a license notice giving the public permission to use the Modified Version under the terms of this License, in the form shown in the Addendum below.

- Preserve in that license notice the full lists of Invariant Sections and required Cover Texts given in the Document's license notice.

- Include an unaltered copy of this License.

- Preserve the section Entitled "History", Preserve its Title, and add to it an item stating at least the title, year, new authors, and publisher of the Modified Version as given on the Title Page. If there is no section Entitled "History" in the Document, create one stating the title, year, authors, and publisher of the Document as given on its Title Page, then add an item describing the Modified Version as stated in the previous sentence.

- Preserve the network location, if any, given in the Document for public access to a Transparent copy of the Document, and likewise the network locations given in the Document for previous versions it was based on. These may be placed in the "History" section. You may omit a network location for a work that was published at least four years before the Document itself, or if the original publisher of the version it refers to gives permission.

- For any section Entitled "Acknowledgements" or "Dedications", Preserve the Title of the section, and preserve in the section all the substance and tone of each of the contributor acknowledgements and/or dedications given therein.