Peeragogy Handbook V1.0/Designs for Co-Working

Here our aim is to develop the productive “paragogical” side of peeragogy through a discussion of the strategies, joys, and sorrows of co-working. It complements the co-facilitation page.

These questions could apply to our working group(s) here, and to pretty much any working group in existence:

- How do you pass the ball?

- How do you keep the energy going?

- How do you diagnose where the group is going and make things “intentional” instead of assumed?

And how do we do all of this in a way that takes learning into account? (The proposed “allowed list” comes from Simon Sinek, by way of Fabrizo Terzi and the FTG.)

Co-working as the flip side of convening

[edit | edit source]Linus Torvalds, interviewed by Steven Vaughan-Nichols for a Hewlett-Packard publication, had this to say about software development:

The first mistake is thinking that you can throw things out there and ask people to help. That's not how it works. You make it public, and then you assume that you'll have to do all the work, and ask people to come up with suggestions of what you should do, not what they should do. Maybe they'll start helping eventually, but you should start off with the assumption that you're going to be the one maintaining it and ready to do all the work. The other thing--and it's kind of related--that people seem to get wrong is to think that the code they write is what matters. No, even if you wrote 100% of the code, and even if you are the best programmer in the world and will never need any help with the project at all, the thing that really matters is the users of the code. The code itself is unimportant; the project is only as useful as people actually find it.

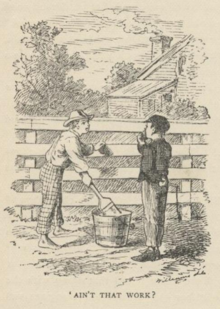

It is important to understand your users -- and remember that contributors are a special class of "user" with a real time investment in the way the project works. We typically cannot "Tom Sawyer" ourselves into leisure or ease just because we manage to work collaboratively, or just because we have found people with some common interests.

The truth is probably somewhere in between Torvalds and Twain. Many people actively want to contribute! For example, on "Wikipedia, the encyclopedia anyone can edit" (as of 2011) as many as 80,000 visitors make 5 or more edits per month. This is interesting to compare with the fact that (as of 2006) "over 50% of all the edits are done by just .7% of the users… 24 people...and in fact the most active 2%, which is 1400 people, have done 73.4% of all the edits." Similar numbers apply to other peer production communities.

A little theory

[edit | edit source]In many natural systems, things are not distributed equally, and it is not atypical for e.g. 20% of the population to control 80% of the wealth (or, as we saw, for 2% of the users to do nearly 80% of the edits). Many, many systems work like this, so maybe there's a good reason for it.

Let's think about it in terms of "coordination" as thought of by the late Elinor Ostrom. She talked about "local solutions for local problems". By definition, such geographically-based coordination requires close proximity. What does "close" mean? If we think about homogeneous space, it just means that we draw a circle (or sphere) around where we are, and the radius of this circle (resp. sphere) is small. An interesting mathematical fact is that as the dimension grows, the volume of the sphere gets "thinner", so the radius must increase to capture the same d-dimensional volume when d grows! Based on this, we might guess that the more dimensions a problem has, the more resources we will need to solve it. From another perspective, the more different factors impact a given issue, in some sense, the less likely there are to be small scale, self-contained, "local problems" in the first place.

If we think about networks instead of homogeneous space, and notice that some nodes in the network have more connections than others, then we see the same issue applies to these nodes: they have more complexity in their immediate region than the others. This might suggest that such "central nodes" (e.g. popular films, popular words, popular websites, popular people) would, by definition, be less discriminating in terms of who/what they couple with. On a certain level (weak ties) this is probably true. But on another level (strong ties) I think it must not be true -- you can't really have it both ways.

Asking for organizations to work on the "local" level of strong ties when they are "really" all about many low-bandwidth weak ties isn't likely to work well. Google is happy to serve everyone's web requests -- but they can't have just anyone walking in off the street and connecting devices their network in Mountain View. (Aside: the 2006 article on Wikipedia quoted above was written by Aaron Swartz, who achieved some notoriety for doing essentially just that, though in his case, it was MIT's network, not Google's.) We might guess that the more institutionally committed someone is, the less likely they are to be able to form deep connections with anyone who is not an integral part of their institution.

Of course, we don't "give up". We aspire to create systems that have both aspects, systems where a "dedicated individual can rise to the top through dint of effort", etc. These systems are well articulated, almost like natural languages, which are so expressive and adaptive that "most sentences have never been said before". In other words, a well-articulated system does lend itself to "local solutions to local problems" -- but only because all words are NOT created equal.

My brothers read a little bit. Little words like 'If' and 'It.' My father can read big words, too, Like CONSTANTINOPLE and TIMBUKTU.

Co-working: what is an institution?

[edit | edit source]We could talk in this section about Coase's theory of the firm, and Benkler's theory of "Coase's Penguin". We might continue quoting from Aaron Swartz. But we will not get so deep into that here: you can explore it on your own!