Professionalism/Michael de Guzman and the Bre-X Scandal

Introduction

[edit | edit source]This chapter explores the 1997 Bre-X gold mining fraud. We examine the enabling forces around the scandal and analyze Michael De Guzman's specific cover-up strategy. Participants include Bre-X management, investors, the Indonesian Government, Freeport-McMoRan, Busang villagers and the Ontario Securities Commission. We discuss evident decision traps that are applicable across industries and professionals.

Timeline of Events

[edit | edit source]Team Formation

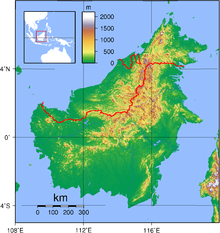

[edit | edit source]In 1988, David Walsh founded Bre-X Minerals Ltd out of his basement in Calgary, Canada.[1] Initially focused on diamond expeditions in the Northwest Territories, Bre-X found little success in its first years of operations. After several failed expeditions, Walsh filed for personal bankruptcy in 1991.[2] To "put some romance into Bre-X," Walsh shifted his company's focus to foreign gold expeditions. He reached out to John Felderhof, a geologist famous for discovering the largest gold mine in Papua New Guinea, and together they targeted the jungles of Indonesia.[3] Felderhof was named General Manager of Bre-X's Indonesian exploration and brought in Michael De Guzman, a Filipino geologist and long-time friend. Following De Guzman's and Felderhof's guidance, Walsh purchased land in Busang on the island of Borneo.[4]

Striking Gold

[edit | edit source]Although over twelve mining companies labeled the land as "worthless", De Guzman and Felderhof were confident they would strike gold. This optimism faded, however, after failing on their first two attempts. "We almost closed the property," said De Guzman, claiming that Felderhof said "close the property" just before their initial hit.[2] After finally striking gold in 1995, Bre-X estimated over 30 million ounces of gold on the property.[1] De Guzman and Felderhof continued to survey the land, and their estimates rose with each newly discovered sample.[5] By 1997, Bre-X's estimate eclipsed 71 million ounces of gold.[4] Felderhof believed the valuations could eventually exceed 200 million ounces, more than the Californian gold rush. When asked about the find, Walsh said "We all find it hard to believe that we're responsible for the largest gold discovery probably in the history of the world."[2]

Stock Price Soars

[edit | edit source]As word of the discovery spread, investors flocked to Bre-X. J.P. Morgan made public statements endorsing the Busang site and Lehman Brothers labeled it "the gold discovery of the century."[1] In 1996, Walsh began trading the once penny-stock on the Toronto Stock Exchange. The stock price soared from 30 cents to $170 in just two years.[6] Local investors saw immediate gains, with one Canadian woman claiming to know "about five new millionaires."[7]

Indonesian Government Intervention

[edit | edit source]As gold estimates soared, the Indonesian government and President Suharto intervened.[4] Fearful that Bre-X lacked the resources necessary to handle the growing gold mine, President Suharto forced Bre-X to enter a partnership with a larger gold mining company. [1] Suharto also did not realize that his country was sitting on such a large reserve of gold and wanted to make sure that he had a piece of the pie. By the end of negotiations, Bre-X held 45% of the land, the Indonesian government owned 40% and Freeport-McMoRan claimed the remaining 15%.[8]

Collapse

[edit | edit source]Six weeks after closing the deal, Freeport-McMoRan began due diligence testing in Busang by completing core holes 1-2m away from the four Bre-X drill-holes that contained the highest gold grades. After failing to strike gold in any of these holes, Freeport requested to meet with De Guzman to discuss their findings. On his way to the meeting, De Guzman committed suicide, jumping out of his helicopter.[9] As news spread of De Guzman's death, fearful investors sold over nine million Bre-X shares.[10] Walsh urged investors to ignore the rumors and launched an independent investigation.[11] To Walsh's dismay, the investigation determined that "the estimated size of the Busang reserve was based on falsified data."[12] Bre-X lost $583 million dollars as the stock fell 80 percent, crashing the Toronto Stock Exchange's computerized trading system.[13] In November of 1997, Bre-X filed for bankruptcy.[14]

The Cover-up

[edit | edit source]Salted Samples

[edit | edit source]In the aftermath of the scandal, Strathcona Mineral Services conducted an independent audit of Bre-X. They discovered that Bre-X had tampered with the core samples, adding gold from an external source.[1] In their report, they commented on the historical significance of the tampering, astounded by the length, scale and accuracy of the tampering operation.[15] The report concluded that a member of the Bre-X team most likely engaged in "salting", sprinkling gold onto samples before shipping them to the lab for testing.[1] Interviews with on-site workers revealed suspect operational procedures. The testing labs were "very downstream" from the mining facility, giving De Guzman privacy to prepare the samples.[16] Workers reported De Guzman leaving open bags of rock samples in his office and often "blend[ing] pulverized rock samples with reddish, white and gold-colored powders" into the samples.[1] Some journalists speculate that initial salting was simply to extend the project, but the salting continued after the enormous estimates returned from the lab.[5]

Volcanic Pool Theory

[edit | edit source]Prior to joining the Bre-X operation, De Guzman developed the "Volcanic Pool Theory." De Guzman believed that when a volcano "collapse[s] back onto itself," gold is created from the "massive buildup of heat and pressure." [2] The "Volcanic Pool Theory" motivated Bre-X's selection of Busang and justified their unorthodox mining practices. Busang's proximity to volcanoes made it the ideal location to test De Guzman's life work and potentially prove his Theory. Under typical mining conditions, after extracting a core sample from the ground, half is sent to the lab for testing and the other half is stored for future audits.[1] De Guzman argued that volcanic pressure causes a non-uniform distribution of gold across the core sample. For this reason, the entire sample must be tested to accurately measure the gold content.[17] This procedure resulted in minimal core sample storage, preventing future auditors from accurately assessing the valuations. [5]

Traps in Decision Making

[edit | edit source]De Guzman surrounded himself with young geologists that recently graduated from college. Their inexperience resulted in minimal questioning of management, despite De Guzman's unorthodox practices. An observer likened the Bre-X team to "the geological equivalent of the batboys for the World Champion Yankees." While they were excited to partake in the gold rush, their inexperience limited their role in the operation.[2] This limited role allowed De Guzman's tactics to go unchecked.

During the due diligence process, several investors questioned Bre-X's testing of the entire core sample. Felderhof responded by asserting De Guzman's expertise, arguing he does "not have time to educate them on the various grade determination methods for gold commonly used on a global basis in the mining industry."[1] Because most investors lacked experience in the mining industry, many blindly trusted the "Volcanic Pool Theory" justification, leading to high valuations and minimal further questioning.[5]

Normalization deviance has also plagued investors in the mining industry. Investors have fallen for similar scandals in the past including a Uranium scandal in Utah in 1954, a Nickel scandal in Australia in 1969 and most recently, a gold mining scandal in China in 2007. Overconfident market expectations caused the stock prices of these companies to soar.[18] Although skepticism of reported findings increases after a scandal like Bre-X is uncovered, decision fatigue eventually settles in and investors fall for similar traps over time.

Aftermath

[edit | edit source]Busang Community Members

[edit | edit source]At the height of Bre-X's valuations, many local villagers moved their families to Busang. Much like the gold rush of California, most of these villagers left everything behind in hope of finding gold. Bre-X encouraged settlement, electrifying local villages and building a new church and kindergarten.[2] Local villagers have remained in the area in hopes of striking gold. Said one villager who pans for gold each day, "There is gold here. If there is someone who was interested to continue the Busang project, please come to Indonesia."[19]

No Criminal Charges

[edit | edit source]Many investors accused Walsh and Felderhof of colluding with De Guzman, citing instances of suspicious behavior. When Bre-X filed for the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, they announced they "prepared, reviewed or verified [their findings] with independent mining experts," but failed to disclose that the samples were always drawn and controlled by Bre-X. Felderhof and Walsh also raised suspicion when they each sold $25 million in Bre-X stock prior to De Guzman's suicide. The courts ruled in favor of Felderhof and Walsh, claiming they "acted with their normal professionalism, which by its very nature bestows credibility."[16] The Judge further believed "Felderhof has proven that he took all reasonable care."[3] The Nasdaq also released a statement claiming that Bre-X passed the SEC's filing and financial requirements.[16]

New Regulations

[edit | edit source]A spokesperson for Nesbitt Burns, an investment company that endorsed Bre-X, argued under the current reglatory climate, "our analysts rely on publicly available information...our experts are not experts in uncovering fraud." He further claimed, "our industry and our clients have been victimized." In the late 1990s, Canadian gold mining companies were not liable for the accuracy of their gold estimates. Because Bre-X did not publicly offer their shares, standardized due diligence was not required.[16] The Ontario Securities Commission passed the NI 43-101 in response to the Bre-X scandal, "prohibit[ing] misleading disclosure" and requiring the "involvement of a qualified person."[20]

Conspiracy Theories

[edit | edit source]Several conspiracy theories have surfaced around the Bre-X scandal. Many people, including the doctor who performed De Guzman's autopsy, believe De Guzman faked his suicide and is still alive today.[6] Workers on site the day Guzman disappeared claimed he was carrying large duffel bags of cash. Some say he ran to South America with a few hundred thousand dollars, while others say it was upwards of hundreds of millions. With this amount of money he could have bribed his way to freedom.[21] Genie De Guzman, his widowed wife, fueled the controversy when she claimed she mysteriously received a payment of $25,000 from Brazil.[22] Another independent investigation found that De Guzman was pushed from the helicopter and served as the "fall guy" for the entire company.[6] It is also possible that De Guzman orchestrated the entire scandal, developing his "Volcanic Pool Theory" and then using it to convince successful prospectors who had fallen on rough times to invest without questioning.

Conclusion

[edit | edit source]Michael De Guzman convinced experienced investors, expert auditors and even Bre-X management that a dry mine was worth over $6 billion. In David Walsh's words, "four and a half years of hard work and the pot at the end of the rainbow is a bucket of slop."[3] De Guzman leveraged his perceived expertise to justify suspect behavior and created a work environment where he could operate unchecked. These tactics to garner trust and seize control are illustrated across cases on ethics. It is a professional's responsibility to identify these red flags and thwart the fraud before it impacts thousands of stakeholders. We focused primarily on the specifics of the Bre-X scandal in this chapter and further analysis on the broader implications would strengthen this case study. A closer look at Freeport-McMoRan or the Indonesian Government as a stakeholder would improve this chapter as well.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Lane McNamara, et al. v. Bre-X Minerals Ltd. (1997, July) Civil Action No. 597CV159. United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas. Retrieved May 8th from http://securities.stanford.edu/filings-documents/1012/BXMNF97/1997725_r05c_97159.pdf

- ↑ a b c d e f Behar, R. (1997, June 9) Jungle Fever: The Bre-X Saga is the Greatest Gold Scam Ever. But to Understand the Enormity of the Fraud, You Had to Be There. Our Man in Borneo Tells his Story. Retrieved May 8th from http://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/1997/06/09/227519/index.htm

- ↑ a b c Stephenson, A. and Seskus, T. (2017, January 26) Behind ‘Gold’: The real story of Bre-X proves life is stranger than fiction. Retrieved May 8th from http://www.calgarysun.com/2017/01/26/behind-gold-the-real-life-story-of-bre-x-proves-life-is-stranger-than-fiction

- ↑ a b c R. v. Felderhof (2007, July 31) Ontario Court of Justice. Retrieved May 8th from http://www.groiaco.com/pdf/Judgment.pdf

- ↑ a b c d Henchek, C. (1998 June) Bre-X: The Lure of False Gold. Engineering and Mining Journal.

- ↑ a b c Dolphin, R. (1996, March 3) Stock of the century: Investors hit jackpot with gold mining. Retrieved May 8th from http://calgaryherald.com/news/local-news/bre-x-the-real-story-and-scandal-that-inspired-the-movie-gold

- ↑ Crowe, K. (1996, March 11) Gold fever sweeps investors after Bre-X discovery. Retrieved May 8th from http://www.cbc.ca/archives/entry/bre-x-gold-fever

- ↑ McNamara v. Bre-X Minerals Ltd., 197 F. Supp. 2d 622 (2001, March 30) U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas. Retrieved May 8th from http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp2/197/622/2430937/

- ↑ Wilton, S. (2007, May 26) The mystery of Michael de Guzman. Retrieved May 8th from http://calgaryherald.com/news/local-news/bre-x-the-real-story-and-scandal-that-inspired-the-movie-gold

- ↑ Calgary Herald and Herald wire services (1997, March 22) Nervous investors pound Bre-X shares. Retrieved May 8th from http://calgaryherald.com/news/local-news/bre-x-the-real-story-and-scandal-that-inspired-the-movie-gold

- ↑ Ewart, S. (1997, March 20) Bre-X geologist plunges to his death from helicopter in Borneo. Retrieved May 8th from http://calgaryherald.com/news/local-news/bre-x-the-real-story-and-scandal-that-inspired-the-movie-gold

- ↑ Bre-X Minerals LTD. (1997, May 4) News Release. Retrieved May 8th from http://www.infomine.com/press_releases/bxm/pr050497bxm.html

- ↑ CNN Money. (1997, May 5) No gold at Bre-X site. Retrieved May 8th from http://money.cnn.com/1997/05/05/companies/brex/

- ↑ Deloitte & Touche Inc. (1997, November 5) Bre-X Minerals LTD., In Bankruptcy. Retrieved May 8th from http://www.insolvencies.deloitte.ca/en-ca/Pages/BRE-X%20MINERALS%20LTD__%20IN%20BANKRUPTCY%20.aspx?searchpage=Search-Insolvencies.aspx

- ↑ Historica Canada. (1997) Bre-X Collapses. Retrieved May 8th from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/bre-x-collapses/

- ↑ a b c d Scheider, H. (1997, May 18) A Lode of Lies: How Bre-X Fooled Everyone. Retrieved May 8th, 2017 from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/inatl/longterm/canada/stories/brex051897.htm

- ↑ Lawrence, M. (1998, March 26) Expert Witness Deposition in Lane McNamara, et al. v. Bre-X Minerals Ltd. Retrieved May 8th from http://securities.stanford.edu/filings-documents/1012/BXMNF97/1998326_o20x_Lawrence.pdf

- ↑ Walker, S.(2016, October 5) Exposing Bubbles, Shysters and Out-and-out Scams. Retrieved May 8th from http://www.e-mj.com/features/6468-exposing-bubbles-shysters-and-out-and-out-scams.html#.WRHQFNLys2y

- ↑ Wilton, S. (2007, May 29) Back to Busang. Retrieved May 8th from http://calgaryherald.com/news/local-news/bre-x-the-real-story-and-scandal-that-inspired-the-movie-gold

- ↑ Ontario Securities Commission (2008, February 8) Mineral Project Disclosure Standards: Understanding NI 43-101. Retrieved May 8th from http://www.osc.gov.on.ca/documents/en/Securities-Category4/rule_20080229_43-101_1day-workshop.pdf

- ↑ Historica Candanada (2005) Bre-X Geologist Mike de Guzman Rumoured to be Alive. Retrieved May 9th from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/bre-x-geologist-mike-de-guzman-rumoured-to-be-alive/

- ↑ Canadian Press (2005, May 25) De Guzman Lives? Singapore Report Cites Cheque from Fallen Bre-X Geologist. Retrieved May 8th from http://www.resourceinvestor.com/2005/05/24/de-guzman-lives-singapore-report-cites-cheque-fallen-bre-x-geologist