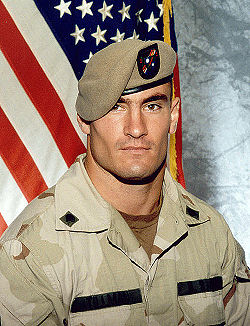

Professionalism/The Pat Tillman case

This chapter explores the details of Pat Tillman's life and the U.S. government's cover up of his death in Afghanistan. It also analyzes what lessons we can gain from this case and how we can apply these lessons our lives.

Early Life

[edit | edit source]On November 6th, 1976, Mary and Patrick Tillman gave birth to their first of three sons— Patrick Daniel Tillman in a small city of California called Fermont. Growing up, Tillman shared a special relationship with his family, especially his brother Kevin who would later enlist with Tillman. Later in life, Tillman became close to his high school friends particularly Marie Ugenti, Tillman’s high school sweetheart. The two would get married right before the Tillman brothers enlisted. In high school, Tillman quickly became the star of the Leland High School football team after initially being cut from the baseball team his freshman year. By the start of his senior year of high school in 1993, Tillman was considered one of the nation’s best players. He was credited with 110 tackles, 31 touchdowns, and averaged 25.7 yards per reception. On December 4th, 1993, Tillman helped Leland win the Central Coast Section (CCS) championship and Tillman was named one of two CCS MVPs.[1] [2]

Despite his achievements as a football star in high school, Tillman was considered too small to play football in college and drew little interest from college programs. However, Arizona State showed interest and Tillman was able to secure the last available scholarship offer. By his junior year, Tillman became a starting linebacker for the Sun Devil’s and was second on the team in tackles. By his senior year, Tillman lead the team in tackles and was named the Pac-10’s defensive player of the year. Like college programs, Tillman was largely ignored by the NFL except for the Arizona Cardinals. Tillman was selected in 1997 as the 226 overall draft pick. In his rookie year, Tillman switched to safety position and started 10 of the 16 games that season. Tillman quickly gained recognition throughout the NFL as an extremely skilled safety. At one point in his career, the St. Louis Rams Tillman a five year, 9 million dollar contract. However, Tillman felt extreme loyalty to the team that drafted him when no one else would and turned down the offer to continue playing for the Cardinals. [1] [2]

Following the attacks of September 11th, Tillman finished the remaining 15 games of the NFL season and following the completion of the season, Tillman enlisted in the Army. He turned down a three year, 3.6 million dollar contract from the Cardinals and with his brother Kevin, who turned down a chance to play professional baseball, the Tillman brothers enlisted. Tillman chose to enlist because he felt his life playing football was no longer important given what had happened to his country. [1] [2] In two different interviews Tillman gave the following quotes:

"My great-grandfather was at Pearl Harbor and a lot of my family has… gone and fought in wars, and I really haven't done a damn thing as far as laying myself on the line like that."[3]

“For much of my life I’ve tried to follow a path I believed important. Sports embodied many of the qualities I deem meaningful: courage, toughness, strength, etc. However, these last few years, especially after recent events, I’ve come to appreciate just how shallow and insignificant my role is. I’m no longer satisfied with the path I’ve been following…it’s no longer important.” [1]

By the June of 2002, the Tillman brothers had finished basic training and by the end of 2002, the brothers had completed the Ranger Indoctrination Program. [1] [2]

The Accident

[edit | edit source]On April 22nd, 2004, Tillman was operating as a member of 2nd Ranger Battalion around Khowst, Afghanistan. Tillman’s platoon, which included his brother Kevin Tillman, was sent out to do a clearing operation in the village of Manah. With them was a broken down HUMMV in tow. One of the platoon’s HUMMV began experience steering problems as a result of towing the HUMMV. At around 9:00 AM local time, the platoon stopped in a village to assess the situation and decided that the HUMMV could no longer be towed. After receiving word from superiors that there would not be support to come get the HUMMV the platoon hired a local tow truck to take the HUMMV with them on the mission. This took several hours as it was difficult for the platoon to organize the tow truck and deal with the curious locals. Superiors advised them to split into two serials (groups) to proceed with the mission. Serial 1, which contained Tillman, was sent on to Manah to complete the sweep mission there. Serial 2’s, containing Kevin Tillman, goal was to go meet with the tow truck driver, go to a hard topped road to drop off the HUMMV, and then to rendezvous with Serial 1 in Manah. Around 4:30 PM, dusk in this location, an ambush occurred on Serial 2 as they drove through a canyon with enemies firing from the canyon’s edge. Hearing the ambush, Serial 1 turned around to provide support for Serial 2. Part of Serial 1, including Tillman, dismounted from their HUMMVs and moved forward to secure the area. At this point Tillman and an Afghani soldier took cover behind a boulder where the Afghani soldier was killed. Tillman deployed a high-density smoke grenade to mark his location as friendly. When the firefight ended and a cease-fire was called, it was found that Tillman had been shot in the head three times and had been killed in action. The platoon immediately suspected that fratricide, friendly fire, was to blame for Tillman’s death. The platoon called their superiors and requested transport for Tillman’s body and the wounded as well as reinforcements to help secure the area. [4]

The Cover Up

[edit | edit source]By 10:00 p.m. on the day of Pat’s death, Kevin Tillman was arriving at Forward Operating Base Salerno. All phones and Internet terminals available to enlisted men had been shut down to prevent information reaching the press before the next of kin was notified. 8:30 a.m. the following day Lieutenant Colonel Jeffrey Bailey arrived on scene and spoke with the soldiers from both serials. Bailey determined that, in accordance with Article 15-6 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, an investigation was necessary and informed his superior saying “I’m sure it’s a fratricide, sir, but I think I owe you the details. Let me do this investigation and I’ll give it to you as quickly as I can.” Bailey appointed Captain Richard Scott to head the 15-6 investigation. Though Scott was a highly regarded officer he was under direct command of those he was expected to investigate. As Bailey was well aware, Article 15-6 required “the investigating officer to be senior in rank to anyone whose conduct or performance he may investigate,” yet this decision that was first of numerous irregularities that spanned years and caused the Tillman family prolonged and significant pain. [1]

Captain Richard Scott completed his 15-6 investigation on the 4th of May, the day after Tillman’s memorial service. The report claimed, among other things, that “leadership played a critical role and greatly contributed to the fratricide incident…” The report proceeded up the chain of command until it reached Colonel Nixon and Lieutenant Colonel Bailey, at which point it disappeared. Additionally, when a 15-6 investigation is initiated, military law dictates that those in command must alert the Criminal Investigation Division (CID), who in turn would complete an independent criminal investigation. When the CID heard of suspected fratricide, they immediately sent a special agent to inquire. The special agent was intercepted by the legal advisor of Bailey’s boss, Major Charles Kirchmaier, who provided fraudulent information and was congratulated on “keeping the CID at bay.” Over the course of three years, four separate investigations were completed: three deficient Army 15-6 investigations and one two-year long investigation conducted by the Department of Defense inspector general’s office, which was also glaringly deficient. [1]

As soon as Bailey informed his superior, Colonel Nixon, that the cause of Tillman’s death was friendly fire, Nixon delivered the shocking news to his boss, Brigadier General Stanley McChrystal. McChrystal in turn shared the information with Lieutenant General Philip Kensinger, commander of U.S. Army Special Operations Command, and General Bryan Brown, commander of U.S. Special Operations Command. From there, the word of fratricide was sent via secret back channels to the highest levels of the Pentagon and the White House. As decreed by a federal statute and several Army regulations, Marie Tillman was supposed to be notified that an investigation was being conducted, even if fratricide was only suspected, and “be informed as additional information about the cause of death becomes known.” In addition to this initial oversight, all those involved with the investigation were under strict orders to say nothing about friendly fire to the Tillman Family. These orders lead to several instances where those involved had to explicitly deceive the Tillman’s, even at the memorial service of their loved one. In fact, the Tillman family wasn’t informed that fratricide was suspected until the 24th of May, when Bailey recognized that it was no longer possible to keep the secret contained. [1]

The glaring deficiencies described above, though they caused a great deal of pain, could all be a terrible collection of oversights and mistakes. Though a number of things happened that removed all doubt as to whether the deceit was intentional. Standard operating procedures for soldiers killed in action require that his or her uniform, and all other appropriate articles, be returned to the United States with the body for use as forensic evidence. When Corporal Tillman’s body was returned to Forward Operating Base Salerno, his uniform, body armor, notebook and other belongings were burned. In addition to the destruction of evidence, McChrystal submitted a falsified award recommendation. It contained misleading information pertaining to the events surrounding Tillman’s death, as well as two forged witness statements. The documents mentioned nothing of fratricide and in fact stated, “Corporal Tillman put himself in the line of devastating enemy fire.” Many times throughout the document it creates the impression that Tillman was killed by enemy fire. By any measure, the recommendation was fraudulent.[1]

After four failed investigations, the Tillman family was summoned to testify before the House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. It was here the Tillman’s learned that punishment was meted out by the same party that was guilty and investigating itself. Of those that were responsible for the death of Corporal Tillman some received written reprimands while a few were “released for standards” – often referred to as a “slap on the wrist.” A soldier can be RFS’d for accidentally discharging a weapon, or talking back to an officer. For their part in the ordeal, both Bailey and Nixon were promoted. Of those responsible for the “cover-up” most received “memoranda of concern” or nothing at all, and the only officer that received anything resembling punishment was Lieutenant General Philip Kensinger Jr., who was censured for lying under oath but had conveniently retired from the army 18 months earlier. Needless to say the Tillman family was stunned.[1]

Lessons

[edit | edit source]Though this is not directly related to engineering, there are a number of things that can be taken away from this case. The first, and perhaps most important lesson, can be learned from Pat Tillman himself. Pat had an incredibly thorough understanding of his ethical perspective and followed it without compromise. This is something that we can all learn from. Regardless of what the circumstances are, always be true to yourself and always stand by what you believe in. The second lesson learned from this case is that self-regulation is a dangerous and easily corruptible practice. The final lesson learned is that no matter how bad the situation or how terrible the outcomes, one should always act with honesty and integrity.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j , Krakauer, J. (2010). Where men win glory. New York, NY: Random House, Inc

- ↑ a b c d , Carter, B. (n.d.). Hero. Retrieved from http://espn.go.com/classic/biography/s/Tillman_Pat.html

- ↑ , Lewis, G, Miklaszewski , J., & Johnson, A. (2004, April 4). Ex-nfl star tillman makes ‘ultimate sacrifice’. Retrieved from http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/4815441/ns/world_news/

- ↑ Military Times .PDF Document copies Copy of US Army CID report