Saylor.org's Ancient Civilizations of the World/Athens

Introduction

[edit | edit source]

Athens is one of the oldest named cities in the world, having been continuously inhabited for at least 7000 years. Situated in southern Europe, Athens became the leading city of Ancient Greece in the first millennium BCE and its cultural achievements during the 5th century BCE laid the foundations of western civilization.

The name of Athens, connected to the name of its patron goddess Athena, originates from an earlier, Pre-Greek language. The etiological myth explaining how Athens acquired this name through the legendary contest between Poseidon and Athena was described by Herodotus, Apollodorus, Ovid, Plutarch, Pausanias and others. It even became the theme of the sculpture on the West pediment of the Parthenon. Both Athena and Poseidon requested to be patrons of the city and to give their name to it, so they competed with one another for the honour, offering the city one gift each. Poseidon produced a spring by striking the ground with his trident, symbolizing naval power. Athena created the olive tree, symbolizing peace and prosperity. The Athenians, under their ruler Cecrops, accepted the olive tree and named the city after Athena. A sacred olive tree said to be the one created by the goddess was still kept on the Acropolis at the time of Pausanias (2nd century AD). It was located by the temple of Pandrosus, next to the Parthenon. According to Herodotus, the tree had been burnt down during the Persian Wars, but a shoot sprung from the stump.

Geography

[edit | edit source]Athens was in Attica, about 30 stadia (3.3 miles , 5.3 km) from the sea, on the southwest slope of Mount Lycabettus, between the small rivers Cephissus to the west, Ilissos to the south, and the Eridanos to the north, the latter of which flowed through the town. The walled city measured about 0.93 miles(1.5 km) in diameter, although at its peak the city had suburbs extending well beyond these walls. The Acropolis was just south of the centre of this walled area. The city was burnt by Xerxes in 480 BC, but was soon rebuilt under the administration of Themistocles, and was adorned with public buildings by Cimon and especially by Pericles, in whose time (461-429 BC) it reached its greatest splendour. Its beauty was chiefly due to its public buildings, for the private houses were mostly insignificant, and its streets badly laid out. Towards the end of the Peloponnesian war, it contained more than 10,000 houses, which at a rate of 12 inhabitants to a house would give a population of 120,000, though some writers make the inhabitants as many as 180,000.

Athens consisted of two distinct parts:

- The port city of Piraeus, also surrounded with walls by Themistocles and connected to the city with the Long Walls, built under Conon and Pericles.

- The City, properly so called, divided into The Upper City or Acropolis, and The Lower City, surrounded with walls by Themistocles.

The Long Walls

[edit | edit source]

The Long Walls consisted of two walls leading to Piraeus, 40 stadia long (4.5 miles, 7 km), running parallel to each other, with a narrow passage between them. In addition, there was a wall to Phalerum on the east, 35 stadia long (4 miles, 6.5 km). There were therefore three long walls in all; but the name Long Walls seems to have been confined to the two leading to the Piraeus, while the one leading to Phalerum was called the Phalerian Wall. The entire circuit of the walls was 174.5 stadia (nearly 22 miles, 35 km), of which 43 stadia (5.5 miles, 9 km) belonged to the city, 75 stadia (9.5 miles, 15 km) to the long walls, and 56.5 stadia (7 miles, 11 km) to Piraeus, Munichia, and Phalerum.

The Acropolis or upper city

[edit | edit source]

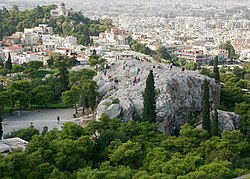

The Acropolis, also called Cecropia from its reputed founder, Cecrops, was a steep rock in the middle of the city; its sides were naturally scarped on all sides except the west end. It was originally surrounded by an ancient Cyclopean wall said to have been built by the Pelasgians. At the time of the Peloponnesian war (431-404 BC) only the north part of this wall remained, and this portion was still called the Pelasgic Wall; while the south part which had been rebuilt by Cimon, was called the Cimonian Wall. On the west end of the Acropolis, where access is alone practicable, were the magnificent Propylaea, "the Entrances," built by Pericles, before the right wing of which was the small Temple of Athena Nike. The summit of the Acropolis was covered with temples, statues of bronze and marble, and various other works of art. Of the temples, the grandest was the Parthenon, sacred to the "Virgin" goddess Athena; and north of the Parthenon was the magnificent Erechtheion, containing three separate temples, one to Athena Polias, or the "Protectress of the State," the Erechtheion proper, or sanctuary of Erechtheus, and the Pandroseion, or sanctuary of Pandrosos, the daughter of Cecrops. Between the Parthenon and Erechtheion was the colossal Statue of Athena Promachos, or the "Fighter in the Front," whose helmet and spear was the first object on the Acropolis visible from the sea.

Lower city

[edit | edit source]The lower city was built in the plain round the Acropolis, but this plain also contained several hills, especially in the southwest part. On the west side the walls embraced the Hill of the Nymphs and the Pnyx, and to the southeast they ran along beside the Ilissos.

History

[edit | edit source]Origins

[edit | edit source]Athens has been inhabited from Neolithic times, possibly from the end of the 4th millennium BC, or nearly 7000 years. By 1412 BC, the settlement had become an important center of the Mycenaean civilization and the Acropolis ("city high" or citadel) was the site of a major Mycenaean fortress whose remains can be recognised from sections of the characteristic Cyclopean walls. On the summit of the Acropolis, cuttings in the rock have been identified as the location of a Mycenaean palace.

Between 1250 and 1200 BC a staircase was built down a cleft in the rock to reach a protected water supply, in a similar way to ones at Mycenae. Unlike other Mycenaean centers, such as Mycenae and Pylos, we do not know whether Athens suffered destruction in about 1200 BC, an event often attributed to a Dorian invasion, and the Athenians always maintained that they were "pure" Ionians with no Dorian element. However, Athens, like many other Bronze Age settlements, went into economic decline for around 150 years following this.

Iron Age burials are often richly provided for and demonstrate that from 900 BC onward Athens was one of the leading centers of trade and prosperity in the region. This position may well have resulted from its central location in the Greek world, its secure stronghold on the Acropolis and its access to the sea, which gave it a natural advantage over inland rivals such as Thebes and Sparta.

According to legend, Athens was formerly ruled by kings, a situation which may have continued up until the 9th century BC. From later accounts, it is believed that these kings stood at the head of a land-owning aristocracy known as the Eupatridae (the 'well-born'), whose instrument of government was a Council which met on the Hill of Ares, called the Areopagus and appointed the chief city officials, the archons and the polemarch (commander-in-chief).

Before the concept of the political state arose, four tribes based upon family relationships dominated the area. The members had certain rights, privileges, and obligations:

- Common religious rights.

- A common burial place.

- Mutual rights of succession to property of deceased members.

- Reciprocal obligations of help, defense and redress of injuries.

- The right to intermarry in the gens in the cases of orphan daughters and heiresses.

- The possession of common property, an archon, and a treasurer.

- The limitation of descent to the male line.

- The obligation not to marry in the gens except in specified cases.

- The right to adopt strangers into the gens.

- The right to elect and depose its chiefs.

During this period, Athens succeeded in bringing the other towns of Attica under its rule. This process of synoikismos – the bringing together into one home – created the largest and wealthiest state on the Greek mainland, but it also created a larger class of people excluded from political life by the nobility. By the 7th century BC social unrest had become widespread, and the Areopagus appointed Draco to draft a strict new code of law (hence the word 'draconian'). When this failed, they appointed Solon, with a mandate to create a new constitution (in 594 BC).

Reform and democracy

[edit | edit source]The reforms that Solon initiated dealt with both political and economic issues. The economic power of the Eupatridae was reduced by forbidding the enslavement of Athenian citizens as a punishment for debt, by breaking up large landed estates and freeing up trade and commerce, which allowed the emergence of a prosperous urban trading class. Politically, Solon divided the Athenians into four classes, based on their wealth and their ability to perform military service. The poorest class, the Thetai, who formed the majority of the population, received political rights for the first time and were able to vote in the Ecclesia (Assembly). But only the upper classes could hold political office. The Areopagus continued to exist but its powers were reduced.

The new system laid the foundations for what eventually became Athenian democracy, but in the short-term it failed to quell class conflict and after 20 years of unrest the popular party, led by Peisistratus, a cousin of Solon, seized power (in 541 BC). Peisistratus is usually called a tyrant, but the Greek word tyrannos does not mean a cruel and despotic ruler, merely one who took power by force. Peisistratus was in fact a very popular ruler, who made Athens wealthy, powerful, and a centre of culture, and instituted Athenian naval supremacy in the Aegean Sea and beyond. He preserved the Solonian constitution, but made sure that he and his family held all the offices of state.

Peisistratus died in 527 BC and was succeeded by his sons Hippias and Hipparchus. They proved to be much less adept rulers and in 514 BC, Hipparchus was assassinated in a private dispute over a young man (see Harmodius and Aristogeiton). This led Hippias to establish a real dictatorship, which proved very unpopular and he was overthrown in 510 BC.

Classical Athens

[edit | edit source]The city of Athens during the classical period of Ancient Greece (508–322 BC) was a notable polis leading the Delian League in the Peloponnesian War against Sparta and the Peloponnesian League. The peak of Athenian hegemony was achieved in the 440s to 430s BC, known as the Age of Pericles.

In the classical period, Athens was a center for the arts, learning and philosophy, home of Plato's Akademia and Aristotle's Lyceum, Athens was also the birthplace of Socrates, Pericles, Sophocles, and many other prominent philosophers, writers and politicians of the ancient world. It is widely referred to as the cradle of Western Civilization, and the birthplace of democracy, largely due to the impact of its cultural and political achievements during the 5th and 4th centuries BC on the rest of the then known European continent.

Rise to power (508–448 BC)

[edit | edit source]Hippias - of the Peisistratid family - established a dictatorship in 514 B.C., which proved very unpopular, although it established stability and prosperity and was eventually overthrown with the help of an army from Sparta, in 511/10 B.C. The radical politician of aristocratic background (the Alcmaeonid family), Cleisthenes, then took charge and established democracy in Athens. The reforms of Cleisthenes replaced the traditional four Ionic "tribes" (phyle) with ten new ones, named after legendary heroes of Greece and having no class basis, which acted as electorates. Each tribe was in turn divided into three trittyes (one from the coast; one from the city and one from the inland divisions), while each trittys had one or more demes (or subdivision of land) —depending on their population—which became the basis of local government. The tribes each selected fifty members by lot for the Boule, the council which governed Athens on a day-to-day basis. The public opinion of voters could be influenced by the political satires written by the comic poets and performed in the city theaters. The Assembly or Ecclesia was open to all full citizens and was both a legislature and a supreme court, except in murder cases and religious matters, which became the only remaining functions of the Areopagus. Most offices were filled by lot, although the ten strategoi (generals) were elected.

Prior to the rise of Athens, Sparta, a city-state with a militaristic culture, considered itself the leader of the Greeks, and enforced an hegemony. In 499 BC, Athens sent troops to aid the Ionian Greeks of Asia Minor, who were rebelling against the Persian Empire. This provoked two Persian invasions of Greece, also known as the Persian Wars, both of which were repelled under the leadership of the soldier-statesmen Miltiades and Themistocles. In 490 the Athenians, led by Miltiades, prevented the first invasion of the Persians, guided by king Darius I, at the Battle of Marathon. In 480. the Persians returned under a new ruler, Xerxes I. The Hellenic League led by the Spartan King Leonidas led 7,000 men to hold the narrow passageway of Thermopylae against the 100,000-250,000 army of Xerxes, during which time Leonidas and 300 other Spartan elites were killed. Simultaneously the Athenians led an indecisive naval battle off Artemisium. However, this delaying action was not enough to discourage the Persian advance which soon marched through Boeotia, setting up Thebes as their base of operations, and entered southern Greece. This forced the Athenians to evacuate Athens, which was taken by the Persians, and seek the protection of their fleet. Subsequently the Athenians and their allies, led by Themistocles, defeated the Persian navy at sea in the Battle of Salamis. It is interesting to note that Xerxes had built himself a throne on the coast in order to see the Greeks defeated. Instead, the Persians were routed. Sparta's hegemony was passing to Athens, and it was Athens that took the war to Asia Minor. These victories enabled it to bring most of the Aegean and many other parts of Greece together in the Delian League, an Athenian-dominated alliance.

Athenian hegemony (448–430 BC)

[edit | edit source]This was a period of Athenian political hegemony, economic growth and cultural flourishing formerly known as the Golden Age of Athens or The Age of Pericles. In the mid-fifth century, what started as an alliance of independent city-states gradually became an Athenian empire. Eventually, Athens abandoned the pretense of parity among its allies and relocated the Delian League treasury from Delos to Athens, where it funded the building of the Athenian Acropolis. With its enemies under its feet and its political fortunes guided by statesman and orator Pericles, Athens produced some of the most influential and enduring cultural artifacts of the Western tradition. The playwrights Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides all lived and worked in fifth century Athens, as did the historians Herodotus and Thucydides, the physician Hippocrates, and the philosopher Socrates.

During the golden age, Athenian military and external affairs were mostly run by the ten strategoi (or generals) who were elected each year by the ten clans of citizens, and whose supreme command was rotated daily. These strategoi had duties which included planning military expeditions, receiving envoys of other states and directing diplomatic affairs. During the time of the ascendancy of Ephialtes as leader of the democratic faction, Pericles was his deputy. When Ephialtes was assassinated by personal enemies, Pericles stepped in and was elected strategos in 445 BCE, a post he held continuously until his death in 429 BCE, always by election of the Athenian Assembly.

Pericles was a great speaker; this quality brought him great success in the Assembly, presenting his vision of politics. One of his most popular reforms was to allow thetes (Athenians without wealth) to occupy public office. Another success of his administration was the creation of the misthophoria (which literally means paid function), a special salary for the citizens that attended the courts as jurors. This way, these citizens were able to dedicate themselves to public service without facing financial hardship. With this system, Pericles succeeded in keeping the courts full of jurors, and in giving the people experience in public life. As Athens' ruler, he made the city the first and most important polis of the Greek world, acquiring a resplendent culture and democratic institutions.

The sovereign people governed themselves, without intermediaries, deciding matters of state in the Assembly. Athenian citizens were free and only owed obedience to their laws and respect to their gods. They achieved equality of speech in the Assembly: the word of a poor person had the same worth as that of a rich person. The censorial classes did not disappear, but their power was more limited; they shared the fiscal and military offices but they did not have the power of distributing privileges.

The principle of equality granted to all citizens had dangers, since many citizens were incapable of exercising political rights due to their extreme poverty or ignorance. To avoid this, Athenian democracy applied itself to the task of helping the poorest in this manner:

- Concession of salaries to public functionaries.

- To seek and supply work to the poor.

- To grant lands to dispossessed villagers.

- Public assistance for invalids, orphans and indigents.

- Other social help.

Most importantly, and in order to emphasize the concept of equality and discourage corruption and patronage, practically all public offices that did not require a particular expertise were appointed by lot and not by election. Among those selected by lot to a political body, specific office was always rotated so that every single member served in all capacities in turn. This was meant to ensure that political functions were instituted in such a way as to run smoothly, regardless of each official's individual capacity.

These measures appear to have been carried out in great measure since the testimony has come to us from, (among others, the Greek historian Thucydides (c. 460 - 400 BCE), who commented: "Everyone who is capable of serving the city meets no impediment, neither poverty, nor civic condition..."

The economic resources of the Athenian State were not excessive. All the glory of Athens in the Age of Pericles, its constructions, public works, religious buildings, sculptures, etc. would not have been possible without the treasury of the Delian League. The treasury was originally held on the island of Delos but Pericles moved it to Athens under the pretext that Delos was not safe enough. This resulted in internal friction within the league and the rebellion of some city-states that were members. Athens retaliated quickly and some scholars believe this to be the period where we should talk about an Athenian Empire instead of a league.

Other small incomes came from customs fees and fines. In times of war a special tax was levied on rich citizens. These citizens were also charged permanently with other taxes for the good of the city. This was called the system of liturgy. The taxes were used to maintain the triremes which gave Athens great naval power and to pay and maintain a chorus for big religious festivals. It is believed that rich Athenian men saw it as an honor to sponsor the triremes (probably because they became leaders of it for the period they supported it) or the festivals and they often engaged in competitive donating.

Pericles governed Athens throughout the 5th century BC bringing to the city a splendor and a standard of living never previously experienced. All was well within the internal regiment of government, however discontent within the Delian League was ever increasing. The foreign affairs policies adopted by Athens did not reap the best results; members of the Delian League were increasingly dissatisfied. Athens was the city-state that dominated and subjugated the rest of Greece and these oppressed citizens wanted their independence.

Previously, in 550 BC, a similar league between the cities of the Peloponnessus—directed and dominated by Sparta—had been founded. Taking advantage of the general dissent of the Greek city-states, this Peloponnesian League began to confront Athens. The events of year 431 BC led to such irreparable damage that the city of Athens finally lost its independence in 338 BC, when Philip II of Macedonia conquered the rest of Greece.

Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC)

[edit | edit source]Resentment by other cities at the hegemony of Athens led to the Peloponnesian War in 431, which pitted Athens and her increasingly rebellious sea empire against a coalition of land-based states led by Sparta. The conflict marked the end of Athenian command of the sea. The war between Athens and the city-state Sparta ended with an Athenian defeat after Sparta started its own navy.

Athenian democracy was briefly overthrown by the coup of 411, brought about because of its poor handling of the war, but it was quickly restored. The war ended with the complete defeat of Athens in 404. Since the defeat was largely blamed on democratic politicians such as Cleon and Cleophon, there was a brief reaction against democracy, aided by the Spartan army (the rule of the Thirty Tyrants). In 403, democracy was restored by Thrasybulus and an amnesty declared.

Corinthian War and the Second Athenian League (395–355 BC)

[edit | edit source]Sparta's former allies soon turned against her due to her imperialist policies, and Athens's former enemies, Thebes and Corinth, became her allies. Argos, Thebes and Corinth, allied with Athens, fought against Sparta in the decisive Corinthian War of 395 BC–387 BC. Opposition to Sparta enabled Athens to establish a Second Athenian League. Finally Thebes defeated Sparta in 371 in the Battle of Leuctra. However, other Greek cities, including Athens, turned against Thebes, and its dominance was brought to an end at the Battle of Mantinea (362 BC) with the death of its leader, the military genius Epaminondas.

Athens under Macedon (355–322 BC)

[edit | edit source]By mid century, however, the northern kingdom of Macedon was becoming dominant in Athenian affairs, despite the warnings of the last great statesman of independent Athens, Demosthenes. In 338 BC, the armies of Philip II defeated Athens at the Battle of Chaeronea, effectively limiting Athenian independence. Athens and other states became part of the League of Corinth. Further, the conquests of his son, Alexander the Great, widened Greek horizons and made the traditional Greek city state obsolete. Antipater dissolved the Athenian government and established a plutocratic system in 322 BC (see Lamian War and Demetrius Phalereus). Athens remained a wealthy city with a brilliant cultural life, but ceased to be an independent power.

In the 2nd century BC, following the Battle of Corinth (146 BC), Greece was absorbed into the Roman Republic as part of the Achaea Province, concluding 200 years of Macedonian supremacy.

Institutions

[edit | edit source]The magistrates

[edit | edit source]

The magistrates were people who occupied a public post and formed the administration of the Athenian state. They were submitted to rigorous public control. The magistrates were chosen by lot, using fava beans (Broad beans). Black and white beans were put in a box and depending on which color the person drew out they obtained the post or not. This was a way of eliminating the personal influence of rich people and possible intrigues and use of favors. There were only two categories of posts not chosen by lot, but by election in the Popular Assembly. These were strategos, or general, and magistrate of finance. It was generally supposed that significant qualities were needed to exercise each of those two offices. A magistrate's post did not last more than a year, including that of the strategoi and in this sense the continued selection of Pericles year after year was an exception. At the end of every year, a magistrate would have to give an account of his administration and use of public finances.

The most honored posts were the ancient archontes, or archons in English. In previous ages they had been the heads of the Athenian state, but in the Age of Pericles they lost their influence and power, although they still presided over tribunals.

There were also more than forty public administration officers and more than sixty to police the streets, the markets, to check weights and measures and to carry out arrests and executions. These executions were carried out by use of bo-staff.

The Assembly of the People

[edit | edit source]The Assembly was the first organ of the democracy. In theory, it brought together in assembly all the citizens of Athens, however the maximum number which came to congregate is estimated at 6,000 participants. The gathering place was a space on the hill called Pnyx, in front of the Acropolis. The sessions sometimes lasted from dawn to dusk. The ecclesia occurred forty times a year.

The Assembly decided on laws and decrees which were proposed. Decisions relied on ancient laws which had long been in force. Bills were voted on in two stages: first the Assembly itself decided and afterwards the Council or βουλη gave definitive approval.

The Council or Boule

[edit | edit source]

The Council or Boule consisted of 500 members, fifty from each tribe, functioning as an extension of the Assembly. These were chosen by chance, using the system described earlier, from which they were familiarly known as "councillors of the bean"; officially they were known as prytaneis (meaning "chief" or "teacher").

The council members examined and studied legal projects, supervised the magistrates and saw that daily administrative details were on the right path. They oversaw the city state's external affairs. They also met at Pnyx hill, in a place expressly prepared for the event. The fifty prytaneis in power were located on grandstands carved into the rock. They had stone platforms which they reached by means of a small staircase of three steps. On the first platform were the secretaries and scribes; the orator would climb up to the second.

Culture

[edit | edit source]The period from the end of the Persian Wars to the Macedonian conquest marked the zenith of Athens as a center of literature, philosophy and the arts. Some of the most important figures of Western cultural and intellectual history lived in Athens during this period: the dramatists Aeschylus, Aristophanes, Euripides and Sophocles, the philosophers Aristotle, Plato and Socrates, the historians Herodotus, Thucydides and Xenophon, the poet Simonides and the sculptor Phidias. The leading statesman of this period was Pericles, who used the tribute paid by the members of the Delian League to build the Parthenon and other great monuments of classical Athens. The city became, in Pericles's words, "the school of Hellas [Greece]."

Attribution

[edit | edit source]"Classical Athens" (Wikipedia) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classical_Athens