Saylor.org's Ancient Civilizations of the World/Philosophy and Science

Hellenistic philosophy

[edit | edit source]Usually, Hellenistic philosophy is described as the period of Western philosophy that developed in the Hellenistic civilization following Aristotle and ending with the beginning of Neoplatonism.

Hellenistic schools of thought

[edit | edit source]Pythagoreanism and Neopythagoreanism

[edit | edit source]Pythagoras

Pythagoreanism was the system of esoteric and metaphysical beliefs held by Greek philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras of Samos (c.570 – c.495 BCE) and his followers, the Pythagorean cult. Pythagoras (c. 570 BCE-495 BCE) was an early Greek philosopher, mathematician and the founder of a religion called Pythagoreanism. He is famous for his eponymous theorem about right triangles: The sum of the areas of the two squares on the legs (a and b) equals the area of the square on the hypotenuse (c). Little reliable information remains about the life of Pythagoras, to the point that historians some historians attribute some of "his" thoughts to his followers. Whether they were the ideas of the man or a school of thought, the ideals influenced many Greek philosophers (a word said to have been coined by Pythagoras, Greek for a "lover of wisdom") including Plato.

Pythagorean thought was dominated by mathematics, and it was profoundly mystical. Pythagorean triangle---and its uses in problem solving]] Pythagoreanism emphasized a belief in mathematics and that numbers are the ultimate philosophical truth. The Pythagoreans are known for their theory of the transmigration of souls, and also for their theory that numbers constitute the true nature of things. They performed purification rites and followed and developed various rules of living which they believed would enable their souls to achieve a higher rank among the gods. Arguably, Pythagoras' most important contribution to society was the Pythagorean Theorem, which states that in any right triangle ABC, where "C" is the hypotenuse, A^2+B^2=C^2.

Two schools of Pythagorean thought eventually developed, one based largely on mathematics and continuing his line of scientific work(the mathēmatikoi or "learners"); the other focusing on his more esoteric teachings (the akousmatikoi or "listeners"), though each shared a part of the other.

Its two main representatives are:

- Pythagoras (570-495 BCE), creator of the Pythagorean theorem, and

- Hippasus (5th century BCE), who is traditionally credited with the discovery of the existence of irrational numbers.

Neopythagoreanism was a school of philosophy reviving Pythagorean doctrines, which was prominent in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. It was an attempt to introduce a religious element into Greek philosophy, worshiping God by living an ascetic life, ignoring bodily pleasures and all sensuous impulses, to purify the soul.

Its main representatives were:

- Nigidius Figulus (98-45 BCE), who incorporated Stoic elements to esoteric Pythagoreanism, to create Neopythagoreanism.

- Numenius of Apamea (2nd century CE), a forerunner of the Neoplatonists.

Epicureanism

[edit | edit source]Epicurus (341 BCE – 270 BCE) was a materialist philosopher, in the sense that Epicurus placed emphasis on only the tangible things of the Earth. For Epicurus, the purpose of philosophy was to attain the happy, tranquil life, characterized by ataraxia—peace and freedom from fear—and aponia—the absence of pain—and by living a self-sufficient life surrounded by friends, enjoying the simple joys of life instead of pursuing wealth, fame or power. Many of his thoughts were groundbreaking for the time. He taught that pleasure and pain are the measures of what is good and evil; death is the end of both body and soul and should therefore not be feared; the gods do not reward or punish humans; the universe is infinite and eternal; and events in the world are ultimately based on the motions and interactions of atoms moving in empty space.

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy based upon the teachings of Greek philosopher Epicurus, founded around 307 BCE. It viewed the universe as being ruled by chance, with no interference from gods. It regarded absence of pain as the greatest pleasure, and advocated a simple life. It was the main rival to Stoicism until both philosophies died out in the 3rd century CE.

Its main representatives were:

- Epicurus (341-270 BCE). For the founder of Epicurianism, the purpose of philosophy was to attain the happy, tranquil life, characterized by peace and freedom from fear by living a self-sufficient life surrounded by friends.

- Zeno of Sidon (1st century BCE), who held that happiness is not merely dependent upon present enjoyment and prosperity, but also on a reasonable expectation of their continuance and appreciation.

Cynicism

[edit | edit source]

The Cynics were an ascetic sect of philosophers beginning with Antisthenes in the 4th century BCE and continuing until the 5th century CE. Their philosophy was that the purpose of life was to live a life of Virtue in agreement with Nature. This meant rejecting all conventional desires for wealth, power, sex, and fame, and by living a simple life free from all possessions. As reasoning creatures, people could gain happiness by rigorous training and by living in a way which was natural for humans. They believed that the world belonged equally to everyone, and that suffering was caused by false judgments of what was valuable and by the worthless customs and conventions which surrounded society. Many of these thoughts were later absorbed into Stoicism.

Its main representatives were:

- Antisthenes (445-365 BCE), the founder of Cynic philosophy; and

- Demetrius (10-80 CE) who wrote: "An easy existence, untroubled by the attacks of Fortune is a Dead Sea."

Cyrenaicism

[edit | edit source]The Cyrenaics were an ultra-hedonist Greek school of philosophy founded in the 4th century BCE, supposedly by Aristippus of Cyrene, although many of the principles of the school are believed to have been formalized by his grandson of the same name, Aristippus the Younger. The school was so called after the Greek city of Cyrene, the birthplace of Aristippus. The Cyrenaics taught that the only intrinsic good is pleasure, which meant not just the absence of pain, but positively enjoyable sensations. Of these, momentary pleasures, especially physical ones, are stronger than those of anticipation or memory. They did, however, recognize the value of social obligation and that pleasure could be gained from altruistic behaviour. The school died out within a century and was replaced by the philosophy of Epicureanism.

Its main representative was:

- Aristippus of Cyrene (435-360 BCE)

Platonism and Neoplatonism

[edit | edit source]

Platonism is the philosophy of Classical Greek philosopher Plato (424/423 BCE – 348/347 BCE) which was maintained and developed by his followers. The central concept of Platonism is the distinction between that reality which is perceptible, but not intelligible, and that which is intelligible, but imperceptible; to this distinction the Theory of Forms is essential. The forms are typically described in dialogues such as the Phaedo, Symposium and Republic as transcendent, perfect archetypes, of which objects in the everyday world are imperfect copies. In the Republic, the highest form is identified as the Form of the Good, the source of all other forms, which could be known by reason. In the Sophist, a later work, the forms being, sameness and difference are listed among the primordial "Great Kinds". In the 3rd century BCE, Arcesilaus adopted skepticism, which became a central tenet of the school until 90 BCE when Antiochus added Stoic elements, rejected skepticism, and began a period known as Middle Platonism. In the 3rd century CE, Plotinus added mystical elements, establishing Neoplatonism, in which the summit of existence was the One or the Good, the source of all things; in virtue and meditation the soul had the power to elevate itself to attain union with the One. Platonism had a profound effect on Western thought, and many Platonic notions were adopted by the Christian church which understood Platonic forms as God's thoughts.

Its main representatives were:

- Plato (424/423–348/347 BCE), writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the foundations of Western philosophy and science.

- Speusippus (407-339 BCE)successor to Plato as head of the Academy.

- Xenocrates (396-314 BCE), who taught that virtue produces happiness, but that external goods can minister to it and enable it to effect its purpose.

- Antiochus of Ascalon (130-68 BCE) generator of the phase of philosophy known as Middle Platonism.

- Plutarch (46-120 CE), author of Parallel Lives and Moralia.

Neoplatonism, or Plotinism, was a school of religious and mystical philosophy founded by Plotinus in the 3rd century CE and based on the teachings of Plato and the other Platonists. Neoplatonism focused on the spiritual and cosmological aspects of Platonic thought, synthesizing Platonism with Egyptian and Jewish theology. They believed that the summit of existence was the One or the Good, the source of all things. In virtue and meditation the soul had the power to elevate itself to attain union with the One, the true function of human beings. It was the main rival to Christianity until dying out in the 6th century.

Its main representatives were:

- Plotinus (205-270 CE), who taught that there is a supreme, totally transcendent "One", containing no division, multiplicity or distinction; beyond all categories of being and non-being.

- Porphyry (233-309 CE), who wrote Isagoge, an introduction to logic and philosophy, that became the standard textbook on logic throughout the Middle Ages.[1]

Peripateticism

[edit | edit source]The Peripatetics was the name given to the philosophers who maintained and developed the philosophy of Aristotle (384-322 BCE). They advocated examination of the world to understand the ultimate foundation of things. The goal of life was the happiness which originated from virtuous actions, which consisted in keeping the mean between the two extremes of the too much and the too little.

Its main representatives were:

- Aristotle (384-322 BCE). His writings were the first to create a comprehensive system of Western philosophy, encompassing morality, aesthetics, logic, science, politics, and metaphysics.

- Strato of Lampsacus (335-269 BCE), who increased the naturalistic elements in Aristotle's thought to such an extent, that he denied the need for an active god to construct the universe, preferring to place the government of the universe in the unconscious force of nature alone.

Pyrrhonian skepticism

[edit | edit source]Pyrrhonian skepticism, was a school of skepticism beginning with philosopher Pyrrho in the 3rd century BCE, and further advanced by Aenesidemus in the 1st century BCE. It advocated total philosophical skepticism about the world in order to attain ataraxia or a tranquil mind, maintaining that nothing could be proved to be true so we must suspend judgement.

- Pyrrho (365-275 BCE). His theory of the impossibility of knowledge (The impossibility of knowledge, even in regard to our own ignorance or doubt, should induce the wise person to withdraw into themselves) is the first and the most thorough exposition of noncognitivism in the history of thought.

- Timon (320-230 BCE)

- Aenesidemus (1st century BCE)

- Sextus Empiricus (2nd century CE)

Stoicism

[edit | edit source]Stoicism was founded by Zeno of Citium in the 3rd century BCE. Based on the ethical ideas of the Cynics, it taught that the goal of life was to live in accordance with Nature. It advocated the development of self-control and fortitude as a means of overcoming destructive emotions. It was the most successful school of philosophy until it died out in the 3rd century CE.

Its main representatives were:

- Zeno of Citium (333-263 BCE) believed that goodness and peace of mind could be gained from living a life of virtue in accordance with nature.

- Seneca (4 BCE-65 CE), Roman philosopher, statesman, and dramatist.

- Marcus Aurelius (121-180 CE), Roman Emperor and author of the Meditations, a literary monument to a philosophy of service and duty, describing how to find and preserve equanimity in the midst of conflict by following nature as a source of guidance and inspiration.

Hellenistic sciences

[edit | edit source]The military campaigns of Alexander the Great spread Greek thought to Egypt, Asia Minor, Persia, up to the Indus River. The resulting Hellenistic civilization produced seats of learning in Alexandria in Egypt and Antioch in Syria along with Greek speaking populations across several monarchies. Hellenistic science differed from Greek science in at least two ways: first, it benefited from the cross-fertilization of Greek ideas with those that had developed in the larger Hellenistic world; secondly, to some extent, it was supported by royal patrons in the kingdoms founded by Alexander's successors.

Especially important to Hellenistic science was the city of Alexandria in Egypt, which became a major center of scientific research in the 3rd century BCE. Two institutions established there during the reigns of Ptolemy I Soter (reigned 323 - 283 BCE) and Ptolemy II Philadelphus (reigned 281 - 246 BCE) were the Library and the Museum. Unlike Plato's Academy and Aristotle's Lyceum, these institutions were officially supported by the Ptolemies; although the extent of patronage could be precarious, depending on the policies of the current ruler.

Hellenistic scholars frequently employed the principles developed in earlier Greek thought: the application of mathematics and deliberate empirical research, in their scientific investigations.

In medicine, Herophilos (335 - 280 BCE) was the first to base his conclusions on dissection of the human body and to describe the nervous system.

Geometers such as Archimedes (ca. 287 BCE – 212 BCE), Apollonius of Perga (ca. 262 BCE – ca. 190 BCE), and Euclid (ca. 325 BCE – 265 BCE), whose Elements became the most important textbook in mathematics until the 19th century, built upon the work of the Hellenic era Pythagoreans. Eratosthenes used his knowledge of geometry to measure the distance between the Sun and the Earth along with the size of the Earth.

Astronomers like Hipparchus (ca. 190 – ca. 120 BCE) built upon the measurements of the Babylonian astronomers before him, to measure the precession of the Earth. Pliny reports that Hipparchus produced the first systematic star catalog after he observed a new star (it is uncertain whether this was a nova or a comet) and wished to preserve astronomical record of the stars, so that other new stars could be discovered. It has recently been claimed that a celestial globe based on Hipparchus's star catalog sits atop the broad shoulders of a large 2nd-century Roman statue known as the Farnese Atlas.

The level of Hellenistic achievement in astronomy and engineering is impressively shown by the Antikythera mechanism (150-100 BCE). It is a 37-gear mechanical computer which computed the motions of the Sun and Moon, including lunar and solar eclipses predicted on the basis of astronomical periods believed to have been learned from the Babylonians. Devices of this sort are not found again until the 10th century, when a simpler eight-geared luni-solar calculator incorporated into an astrolabe was described by the Persian scholar, Al-Biruni. Similarly complex devices were also developed by other Muslim engineers and astronomers during the Middle Ages.

The interpretation of Hellenistic science varies widely. At one extreme is the view of the English classical scholar, Cornford, who believed that "all the most important and original work was done in the three centuries from 600 to 300 BCE." At the other is the view of the Italian physicist and mathematician, Lucio Russo, who claims that scientific method was actually born in the 3rd century BCE, to be forgotten during the Roman period and only revived in the Renaissance.[2]

Hellenistic astronomy

[edit | edit source]Planetary models and observational astronomy

[edit | edit source]

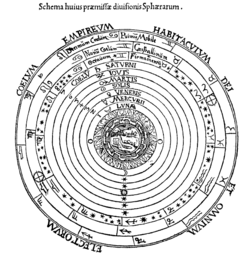

In classical Greece, astronomy was a branch of mathematics; astronomers sought to create geometrical models that could imitate the appearances of celestial motions. The Eudoxan system used a two-sphere geocentric model, which divided the cosmos into two regions:

- A spherical Earth, central and motionless (the sublunary sphere).

- A spherical heavenly realm centered on the Earth, which may contain multiple rotating spheres made of aether

However, the Eudoxan system had several critical flaws. One was its inability to predict motions exactly. Callippus, a Greek astronomer of the 4th century, attempt to correct this flaw by adding seven spheres to Eudoxus' original 27. But, some flaws persisted: the inability of his models to explain why planets appear to change speed; and its inability to explain changes in the brightness of planets as seen from Earth. Because the spheres are concentric, planets will always remain at the same distance from Earth. This problem was pointed out in Antiquity by Autolycus of Pitane (c. 310 BCE).

Apollonius of Perga (c. 262 BCE–c. 190 BCE) responded by introducing two new mechanisms that allowed a planet to vary its distance and speed: the eccentric deferent and the deferent and epicycle. The deferent is a circle carrying the planet around the Earth. (The word deferent comes from the Latin ferro, ferre, meaning "to carry.") An eccentric deferent is slightly off-center from Earth. In a deferent and epicycle model, the deferent carries a small circle, the epicycle, which carries the planet. The deferent-and-epicycle model can mimic the eccentric model, as shown by Apollonius' theorem. It can also explain retrogradation, which happens when planets appear to reverse their motion through the zodiac for a short time. Modern historians of astronomy have determined that Eudoxus' models could only have approximated retrogradation crudely for some planets, and not at all for others.

In the 2nd century BCE, Hipparchus, aware of the extraordinary accuracy with which Babylonian astronomers could predict the planets' motions, insisted that Greek astronomers achieve similar levels of accuracy. Somehow he had access to Babylonian observations or predictions, and used them to create better geometrical models. For the Sun, he used a simple eccentric model, based on observations of the equinoxes, which explained both changes in the speed of the Sun and differences in the lengths of the seasons. For the Moon, he used a deferent and epicycle model. He could not create accurate models for the remaining planets, and criticized other Greek astronomers for creating inaccurate models.

Hipparchus also compiled a star catalogue. According to Pliny the Elder, he observed a nova (new star). So that later generations could tell whether other stars came to be, perished, moved, or changed in brightness, he recorded the position and brightness of the stars. Ptolemy mentioned the catalogue in connection with Hipparchus' discovery of precession. (Precession of the equinoxes is a slow motion of the place of the equinoxes through the zodiac, caused by the shifting of the Earth's axis). Hipparchus thought it was caused by the motion of the sphere of fixed stars.

Heliocentrism and cosmic scales

[edit | edit source]In the 3rd century BCE, Aristarchus of Samos proposed an alternate cosmology (arrangement of the universe): a heliocentric model of the solar system, placing the Sun, not the Earth, at the center of the known universe (hence he is sometimes known as the "Greek Copernicus"). His astronomical ideas were not well-received, however, and only a few brief references to them are preserved. We know the name of one follower of Aristarchus: Seleucus of Seleucia.

Aristarchus also wrote a book On the Sizes and Distances of the Sun and Moon, which is his only work to have survived. In this work, he calculated the sizes of the Sun and Moon, as well as their distances from the Earth in Earth radii. Shortly afterwards, Eratosthenes calculated the size of the Earth, providing a value for the Earth radii which could be plugged into Aristarchus' calculations. Hipparchus wrote another book On the Sizes and Distances of the Sun and Moon, which has not survived. Both Aristarchus and Hipparchus drastically underestimated the distance of the Sun from the Earth.[3]

Hellenistic mathematics

[edit | edit source]During the Hellenistic period, Greek mathematics merged with Egyptian and Babylonian mathematics to give rise to a Hellenistic mathematics.

Even though, mathematical texts written in Greek have been found in Greece, Egypt, Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, and Sicily, Alexandria in Egypt, which attracted mathematics scholars from across the Hellenistic world, mostly Greek and Egyptian, but also Jewish, Persian, Phoenician and even Indian scholars.

Greek mathematician Archimedes of Syracuse (c. 287 BCE – c. 212 BCE) became one of the leading scientists in classical antiquity. He was able to use infinitesimals in a way that is similar to modern integral calculus. Using a technique dependent on a form of proof by contradiction he could give answers to problems to an arbitrary degree of accuracy, while specifying the limits within which the answer lay. This technique is known as the method of exhaustion, and he employed it to approximate the value of π (Pi). In The Quadrature of the Parabola, Archimedes proved that the area enclosed by a parabola and a straight line is 4/3 times the area of a triangle with equal base and height. He expressed the solution to the problem as an infinite geometric series, whose sum was 4/3. In The Sand Reckoner, Archimedes set out to calculate the number of grains of sand that the universe could contain. In doing so, he challenged the notion that the number of grains of sand was too large to be counted, devising his own counting scheme based on the myriad, which denoted 10,000.[4]

Attribution

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Hellenistic Philosophy" (Wikipedia) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hellenistic_philosophy

- ↑ "History of Science in Classical Antiquity" (Wikipedia) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Science_in_the_Hellenistic_period#Hellenistic_period

- ↑ "Greek astronomy" (Wikipedia) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_astronomy#Hellenistic_astronomy

- ↑ "Greek Mathematics" (Wikipedia) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_mathematics#Hellenistic