Saylor.org's Ancient Civilizations of the World/Religion and Language

The Byzantines and the Orthodox Church

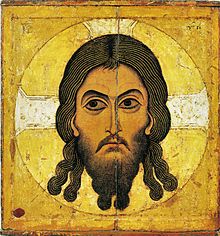

[edit | edit source]As the continuation of the Roman Empire, the Byzantines retained the administrative and financial infrastructure to maintain strong state influence over the church. The Byzantine Emperor became Christ's representative on Earth and it was his job to spread the faith to pagans, as well as to oversee the material realities of running the church. The Emperor maintained a strong grip over the church, but never in an officially delegated role. The Emperor used his power to make the Patriarchate of the capital city of Constantinople the most powerful and prestigious center of all Christendom well until the era of the crusades. To represent the power of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, Emperor Justinian funded the construction of the monumental Hagia Sophia church.

Language

[edit | edit source]The original language of the government of the Empire, which owed its origins to Rome, had been Latin, and this continued as its official language until the 7th century when it was effectively changed to Greek by Heraclius. Scholarly Latin rapidly fell into disuse in the Empire, but it still retained some ceremonial importance. In parts of the Empire that would eventually be known as Romania, Latin lingered around to form the basis of the Romance language of Romanian. Even before the fall of the Roman Empire, however, Greek remained a much more universal and important language for trade and the Christian Church in the Eastern Empire. The prevalence of Greek in the Empire, particularly in the writing of the Eastern Orthodox Church, was a direct link to the development of the Cyrillic alphabet. This alphabet would be applied to the Russian language and countless other slavic languages still spoken today.

The Byzantine Commonwealth

[edit | edit source]

With the conflict between the Church of Rome and the Church of Constantinople (what would become the Catholic and Orthodox Churches), the Byzantines looked to spread their ideas about Christianity closer to home. In the middle of the ninth century, two Byzantine monks who happened to be brothers, known by their monastic names Cyril and Methodius, embarked on a project to convert the Slavs to Christianity. Since the Slavs did not have a system of writing, they had to create one in order to translate the Bible for the Slavs. They created an alphabet, which would later evolve into the Cyrillic alphabet, named for Cyril. They journeyed to what is now Moravia, in the Czech Republic, and preached Christianity. They were opposed both by pagan Slav leaders and by Catholic bishops. In 868, they had to travel to Rome to get the pope’s support to continue their missionary work, and Cyril died there. Methodius returned to the Slavs and continued his project of conversion. After he died, however, a new pope came into power and drove Cyril and Methodius’s followers from the Slavs. Still, Byzantine Christianity flourished among the Slavs thanks to the work already accomplished by Cyril and Methodius, and exiled followers of Methodius ended up fleeing to the Bulgarian Empire. They gained influence, converted the Bulgar king, Boris-Michael, and introduced Orthodox Christianity to the populace. Soon the Bulgars would rival the Byzantines in their commitment to Orthodox Christianity. This was the beginning of the Byzantine Commonwealth, a collection of nations united by their shared Orthodox Christian tradition, which brought with it the customs and ideas of the Byzantines. Perhaps the most important group in this commonwealth was the Rus, who later became known as the Russians. Converted to Orthodox Christianity slightly later, in 998, they inherited much of the Byzantine cultural legacy.

Attribution

[edit | edit source]"The Byzantine Empire" (Wikipedia) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantine_Empire