Saylor.org's Comparative Politics/Social Democracy

Socialism

[edit | edit source]In its early forms, socialism was a reaction against the stark inequality and misery produced by the Industrial Revolution and emerging capitalist economies, where those with property had political voice but those without were open to exploitation and oppression.

Though many somehow confuse communism and socialism, they are two different things. Socialism is concerned with welfare of the people, and as such is concerned with providing healthcare and education and the provision of other necessities of a healthy life in order to create a more 'level' society. The reasons for nationalization of industry and other aspects of society vary depending on the specific socialist system.

Communism also has these goals in mind, but is very anti-capitalistic in nature. Unlike communism, one of the corner stones of socialism is to have the state own all capital and natural resources within its sovereign territory. This means that the people being represented by the government, will control everything and thus social classes would be greatly undermined or eliminated altogether (a Communist ideal).

So, increasing education so that people may properly elect representatives, providing high-quality media that is untainted by private interests, and reducing apathy are often socialistic goals. The main difference between Communism and Socialism are that Socialists seek change through government.

Communists feel this is slow, this is reflected by Marx in his books, and thus the need for revolution, which would let them quickly change things. Marx argued that the powerful had never, throughout history, willingly relinquished their power and that revolution would be necessary to overthrow capitalism. History has many examples by which socialists have achieved change, and many countries have a democratic socialist party in power.

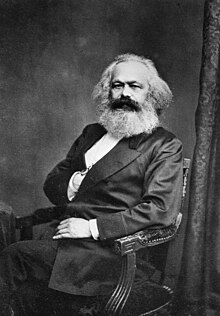

Karl Marx

[edit | edit source]"A spectre is haunting Europe---the spectre of communism"- Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto

Perhaps no thinker of the Modern Era is as misunderstood or misinterpreted as Karl Marx (1818-1883). Whether one views him as an ingenious prophet or a detestable man, Karl Marx's influence is still felt in the world more than a century after his death. At the core of Marxist philosophy is the principle of 'dialectical materialism' or 'historical materialism'.

As a young man, Marx was a devotee to the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who conceived history as a dialectical process. Hegel argued that history was the process of the status quo of the era (the thesis) clashing with a new way of life (the antithesis) to push forward the next era of history (the synthesis).

Marx took this basic dialectical idea and argued that the clash of thesis and antithesis was always one between classes, one that revolved around who owned the means of production. Marx saw an evolutionary change in European society from agrarian feudalism to urban mercantilism to industrial capitalism. Marx believed the next stage of the historical dialectic to be that of the industrial workers taking control of the means of production (Communism).

In the 20th century, several variations of Marx's philosophy emerged from the myriad of Communist leaders: Leninism, Stalinism, Maoism. Each one of these ideologies strayed quite strongly from Marx's original conception of history. Before their respective revolutions, both Russia and China remained largely agricultural societies with large peasant populations. True Marxists would argue that it was impossible to skip right from the agrarian feudal stage of development straight to communism.

The core of these communistic doctrines was to push through this period of history through rapid industrialization and the often deadly means by which these goals were achieved.