Transportation Deployment Casebook/2024/Philippine National Road Network

The Philippine National Road Network is a collection of roads constructed, maintained, and upgraded by the government of the Republic of the Philippines, through its road infrastructure arm, the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH). Roads are a primary mode of land transportation in the Philippines. Although the country is an archipelago, its national highway network is interconnected with roll-on, roll-off ports which connect most of the islands.

Advantages

[edit | edit source]The growing road network of 35,164 kilometers [1] at present has always been given primary focus by the government for continuous improvement as it is strongly tied with the economic development of the country. Its main advantages being:

- Connecting all the islands from north to south

- Consistently implementing highway design and safety standards throughout the country

- Generating jobs through construction and maintenance projects

Main Markets

[edit | edit source]Funding for the road network is sourced from government revenues and as a result, the national road network of the Philippines is not tolled. Unlike the United States Interstate Highway System, permitted types of vehicles, including motorcycles, private cars, trucks, and buses, can freely traverse the road without payment. Nevertheless, inter-island movements would require payment to the ships which carry the vehicles from one island to another.

Background and History

[edit | edit source]Geography and its Implications

[edit | edit source]The Philippines is an archipelago situated in Southeast Asia surrounded by the Pacific Ocean in the east, Taiwan in the north, South China Sea in the west, Malaysian state of Sabah in the southwest, and Celebes Sea and Indonesia in the south. The country is divided into three major island groups namely, Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. While Luzon and Mindanao are larger islands with smaller islands, Visayas is a collection of several islands.

With the said geography, land transport may only be limited to the network of roads in each island, if there was any in the pre-colonial times. At present, land transportation is complemented by maritime travel by accessing roll-on, roll-off ports which ferry vehicles from one island to another. Moreover, moving around the Philippines can be done by land, sea, or air travel with the latter being the fastest and convenient, but at the same time a fairly more expensive option.

Pre-Colonial Era

[edit | edit source]

While records of pre-colonial land transport mode are not evident, it has been apparent that the area where the present-day Philippines is situated played an important role in the maritime movement of people, material culture, and ideas. Inter-island movement of people, including farmer Austronesian-speaking communities from China and Taiwan, [2] already existed. Fishing and farming are the main sources of food of the indigenous Filipinos who lived mostly in small village communities. Its well-preserved rice terraces in the modern-day province of Ifugao showed pre-colonial prowess in the field of irrigation.

Spanish and American Colonial Period

[edit | edit source]

Despite various communities existing in the archipelago in the prior years which can potentially influence the development of the road network of the Philippines, its earliest record can be traced during the Spanish occupation of the Philippine archipelago. Forced labor enabled the construction of the first roads in the Philippines dating as early as 1565. A well-preserved cobblestone road example is in Calle Crisologo located in Vigan, a city in the province of Ilocos Sur in Luzon island. The city is considered as one of the most intact Spanish planned colonial towns in Asia [3].

Forms of transportation began to evolve especially with the use of the calesa, a horse-drawn carriage. Horses are not a local fauna in the Philippines and were imported from other countries. Prior to its availability, carabaos or an indigenous species of water buffalos were used to draw the carriages [4].

The roots of the present-day DPWH came from two colonial government entities, the Bureau of Public Works and Highways (Oficina de Obras Publicas y Carreteras) and the Bureau of Communications and Transportation (Oficina de Comunicaciones y Transportes) in 1868 [5].

Thirty years later, with the declaration of Philippine independence, an organic revolutionary government decree was issued by the first Philippine president, Emilio Aguinaldo, on June 23, 1898 creating the Department of War and Public Works[5]. This government office was tasked to primarily construct and maintain roads and bridges in the country. Building of trenches as well as fortifications necessary for the ongoing war were also under the jurisdiction of this body.

Not long after its declared independence, the Philippines went under the American rule after Spain ceded the archipelago with the United States (US). In turn, the construction and maintenance of the national roads went under the control of the US Army engineers. When the World War II broke out in 1941, the Philippine government ceased its operation almost entirely and was occupied by the Japanese from 1942 to 1945.

The Philippine National Road Network

[edit | edit source]The United States recognized the independence of the Philippines on July 4, 1946. At this time, most of the infrastructure including roads were damaged during the World War II. Thus, the United States Bureau of Public Roads assisted the war-torn country in undergoing repairs as well as implementing a national highway program under the Philippine Rehabilitation Act of 1946 [5]. The US authorized the release of USD73.00 million or USD1.15 billion adjusted for present-day values for this purpose [6].

The rehabilitation works eventually paved the way in the realization of the Philippine National Road Network. The first recorded comprehensive policy for the classification of roads in the Philippines was Executive Order No. 483, Series of 1951 [7], which established the limits of public roads and declaring which roads are under the jurisdiction of the national government for maintenance as well as construction in the case for new roads [8].

| Classification | Minimum width | Connections | Jurisdiction and Source of Funding |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Road | 20 meters |

|

Department of Public Works and Communications |

| Provincial Road | 15 meters |

|

District Engineers under the supervision of the Department of Public Works and Communications |

| City and Municipal Road | 10 meters |

|

City/Municipal Government |

Philippine Highway Act of 1953

[edit | edit source]In 1953, the Philippine Highway Act was passed which supported an administrative mechanism for the improvement and maintenance of national roads and bridges [9]. An equitable management of funds across the provinces of the Philippines was also mandated to ensure the strategic development of the road network.

Some city and municipal roads gained more strategic value for national development. However, due to it being under the watch of local government units, it did not enjoy the same amount of funding the national roads received for maintenance and upgrading. Thus, Executive Order No. 113, Series of 1955 was signed by then President Ramon Magsaysay, which aimed to reclassify roads by categorizing national roads into two namely, primary and secondary, and important provincial and city roads were labeled as “national aid” roads. This allowed local governments access to national government funding for their provincial and city roads [10].

From Growth to Maturity

[edit | edit source]As the interpretations of the existing policies over national roads continued to evolve, the national road network length became shorter or longer over the next 15 years. In the same duration, the Department of Public Works and Communications had several reorganizations of its structure including becoming the Department of Public Works, Transportation, and Communication (BPWTC)[11].

The Pan-Philippine Highway System

[edit | edit source]

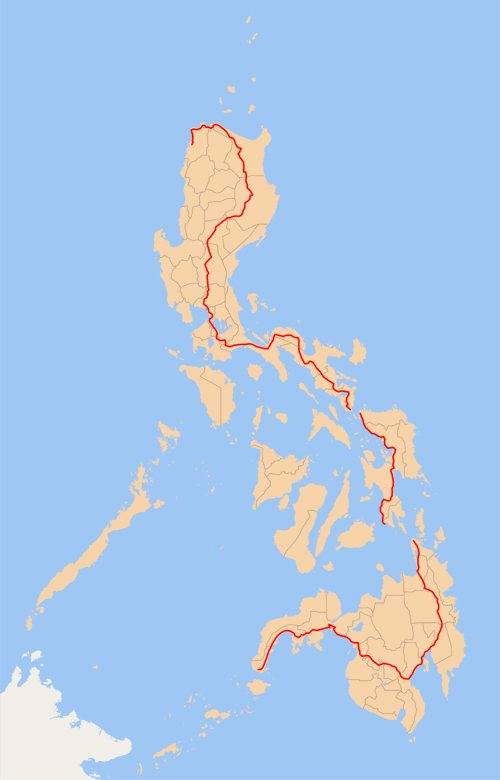

A priority project of Diosdado Macapagal who served president from 1961 to 1965, the Pan-Philippine Highway began construction. The Bureau of Public Highways under the DPWTC fostered the construction of 7,633 kilometers of national, provincial, city, and municipal roads between 1962 and 1964. Several bridges were also built and improved with a cumulative length of 3,500 meters [12].

Throughout the Philippines, the Pan-Pacific Highway has an overall length of 3,379.73 kilometers connecting the three major island groups of the Philippines – Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao [13]. This highway which forms part of the Philippine National Road Network that is presently known as Asian Highway 26 (AH26) of the Asian Highway Network.

Most of the construction of the said highway and other national roads continued during the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos, Sr. funded through foreign loans. Between 1978-1982, the completion of its regional network in Visayas and Mindanao were undertaken. The massive infrastructure development at this time aimed to generate jobs as well as develop local skills and indigenous resources [14].

Martial Law Years

[edit | edit source]Marcos, Sr. served for three terms as president of the Philippines from 1965-1969, 1969-1972, and 1981-1986, wherein during the second term he declared Martial Law (1972-1981). The government at this time consolidated all infrastructure functions into the Department of Public Works, Transportation, and Communications (DPWTC) as part of its Integrated Reorganization Plan to optimize its operations [15]. Under this Department, the Bureau of Public Highways became the Department of Public Highways in 1974, separate from the DPWTC.

In 1976, there was a shift in the form of government which yet again resulted into the renaming of the two departments into ministries – Ministry of Public Works, Transportation, and Communications (MPWTC) and Ministry of Public Highways (MPH). In 1979, further restructuring happened and the MPWTC were divided into two more entities, Ministry of Transportation and Communications (MOTC) and Ministry of Public Works (MPW).

During the leadership of Marcos, infrastructure development was a vital economic tool. However, in 1981, the increased interest rates resulting from the recession of the United States bloated the cost of loans of the Philippines. The Philippine economy declined along with other debt dependent countries in the developing world [16]. This likely also resulted with the merger [17] of MPW and the MPH in 1981 as the Ministry of Public Works and Highways (MPWH) as an austerity measure as well as streamlining the infrastructure services of the Philippines.

Post-Martial Law Years

[edit | edit source]Despite the stunted growth of the road network due to economic pressures, the national road length was aimed to be increased by 55 percent by 1987. The road network development was now focused on the intensive construction of farm-to-market linkages. Visayas and Mindanao which did not receive much infrastructure support was given priority. In addition, an estimated 7,600 kilometers of the national roads were due for rehabilitation, improvement or upgrading [18].

The shift of power from Marcos, Sr. to Corazon Aquino marked more funding for other infrastructure sectors as well as support for the science and technology as well as education sector. In 1987, following the new constitution of the Philippines being applied up to present, the education sector is mandated to receive the top share of the national budget. In addition, the MPWH reverted into a government department and is now called the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH). The government targeted that 55 percent of the national roads will be paved [19].

| Country | Road Density (km/sq km) | Paved Road Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| The Philippines | 0.63 | 0.20 |

| Vietnam | 0.46 | 0.35 |

| Thailand | 0.42 | 0.82 |

| Malaysia | 0.20 | 0.74 |

| Indonesia | 0.19 | 0.47 |

By the end of the administration of Aquino transitioning to the leadership of Fidel Ramos in 1993, 3,858 kilometers of national roads were constructed, upgraded, or rehabilitated by the DPWH [20]. In 1997, the total road network (including local roads) of the Philippines reached 190,030 kilometers and translated to an overall 0.63 kilometers of road per square kilometer but continued to lag behind Malaysia and Thailand in terms of paved road ratio [21]. Thus, most of the efforts done in this time was to increase the paved road ratio. To access more funding, roads which earned more strategic importance were converted into national roads.

Strong Republic Nautical Highway System

[edit | edit source]In 2004, the Philippines now has approximately 202,000 kilometers of roads of which a mere 15 percent was within the national road network maintained by the DPWH. The roll-on, roll-off vessel operations became a new way of further integrating the national road network across the archipelago and complement the earlier Pan-Philippine Highway System situated at the country’s east. Although started in 2003 by then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, the Strong Republic Nautical Highway System became more apparent as more traffic demand was generated prompting improvements in the national road network[22].

- Strong Republic Nautical Highway System

-

Western Nautical Highway

-

Central Nautical Highway

-

Eastern Nautical Highway

Public transport also benefited in the 919-kilometer nautical highway system wherein buses from Manila as well as key development centers can now travel through the national road up to the ports where they are ferried by ships to other islands and continue with their journey by land.

Current Functional Classification of Roads

[edit | edit source]Between 2009 to the present, several issuances were issued by the DPWH pertaining the national road network. The policies governing the national budget for road maintenance and upgrading kept changing as local governments with minimal funding sources turn to the national government for the improvement of their roads. To resolve such issue, the DPWH issued Department Order No. 133, Series of 2018 which effectively defined in detail the functional classification of roads. This maintained the integrity of the national road network and prevented potential allocation of funds for local roads[23].

| Classification | Sub-Class | Connections | Jurisdiction and Source of Funding |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Road | National Primary Road |

|

DPWH |

| National Secondary Road |

|

DPWH | |

| National Tertiary |

|

DPWH | |

| Local Road | Provincial Road |

|

Provincial Engineering Office |

| City/Municipal Road |

|

City/Municipal Engineering Office | |

| Barangay Road |

|

City/Municipal Engineering Office | |

| Expressways |

|

Private Sector Operator |

Future Prospects

[edit | edit source]Allocation of government resources have continued to be a challenge to the ever-growing needs of road transport. Thus, the definition of the national road continues to be ambiguous and is prone to misalign limited funding of the government. In addition, the increased car ownership in the Philippines [24]has also manifested continued demand for more road capacity which can fall prey with further traffic congestion due to induced demand. The direction of the Philippine National Road Network can either be build more roads or improve other means of transport such as public transportation.

The roll-on, roll-off port which complement the national road network may become less useful in the future as the government eyes connecting the islands with physical bridges[25] with several already in the detailed engineering design stage. This may eventually lead into yet another birth stage with the islands connected and increase for national road demand.

Quantitative Analysis

[edit | edit source]Methodology

[edit | edit source]With the road length information obtained from the DPWH[26] and the Philippine Statistical Yearbooks[27], the life cycle stages of the development of the Philippine National Road Network were determined by means of an S-Curve using three-parameter function as described by the equation:

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Predicted system in year t | |

| Approximate saturation status level | |

| Coefficient | |

| Time (in years) | |

| Inflection time (in year) where half of K is achieved |

In estimating the saturation status level K, as well as coefficient, b, the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression was used. The coefficients being calculated through the intercept method, as follows:

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Dependent variable () | |

| Year |

S-Curve and Life Cycle Stage

[edit | edit source]

The S-Curve and the Life Cycle Stages of the Philippine National Road Network from the passing of the Philippine Highway Act in 1953 up to the present shows a good fit. The birth stage shows a rapidly growing system until 1958. The stagnated years are due to the absence of data during this period until 1965 where it decreased significantly due to policy changes under the new administration of Marcos, Sr. A rapid increase can be observed until 1971 when it reached its maturity during the aggressive construction works done in the system. At 1973, where presumably most of the road network was established, it coincided with the inflection point.

Interestingly, it can be observed that the actual kilometers of national road were either below or close to the predicted length between 2009 and 2018. And after the passage of Department Order No. 133, Series of 2018, where national road classification was made much clearer, the national road network began to move further above than the predicted values. This can indicate that there can be further growth of the network in the future.

| Variable | Definition | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Saturation Status Level | 43,000 | |

| Coefficient | 0.026 | |

| R-squared (Coefficient of Determination) | 0.9689 | |

| Inflection time (year) | 1973 |

Annual Data

[edit | edit source]| Year | Length (kilometers) | Predicted Length (kilometers) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1954 | 15960.94 | 16108 | First record of the road network |

| 1955 | 16474.88 | 16378 | |

| 1956 | 17095.07 | 16649 | |

| 1957 | 17881.40 | 16922 | |

| 1958 | 18711.18 | 17196 | No further data available (between 1959 and 1964) |

| 1959 | 18711.18 | 17472 | |

| 1960 | 18711.18 | 17749 | |

| 1961 | 18711.18 | 18027 | |

| 1962 | 18711.18 | 18307 | |

| 1963 | 18711.18 | 18588 | |

| 1964 | 18711.18 | 18870 | |

| 1965 | 16189.35 | 19152 | Start of the Pan-Philippine Highway |

| 1966 | 16615.96 | 19436 | |

| 1967 | 17434.01 | 19720 | |

| 1968 | 18096.59 | 20005 | |

| 1969 | 19698.40 | 20291 | |

| 1970 | 20066.08 | 20576 | |

| 1971 | 21315.38 | 20863 | |

| 1972 | 21643.28 | 21149 | |

| 1973 | 22878.00 | 21436 | |

| 1974 | 24502.00 | 21722 | |

| 1975 | 21340.58 | 22009 | |

| 1976 | 21304.24 | 22295 | |

| 1977 | 22740.47 | 22581 | |

| 1978 | 22826.24 | 22867 | |

| 1979 | 22912.00 | 23152 | |

| 1980 | 23641.10 | 23436 | |

| 1981 | 23659.73 | 23720 | US Recession (Interest rates for foreign loan increased) |

| 1982 | 23738.44 | 24003 | |

| 1983 | 24136.77 | 24286 | |

| 1984 | 25097.70 | 24567 | |

| 1985 | 26259.22 | 24847 | |

| 1986 | 26237.50 | 25126 | |

| 1987 | 26081.99 | 25404 | Organization of present-day DPWH |

| 1988 | 26070.05 | 25680 | |

| 1989 | 26070.05 | 25955 | |

| 1990 | 26272.03 | 26229 | |

| 1991 | 26422.17 | 26501 | |

| 1992 | 26544.44 | 26771 | |

| 1993 | 26593.59 | 27039 | |

| 1994 | 26153.61 | 27306 | |

| 1995 | 26720.23 | 27571 | |

| 1996 | 27639.37 | 27834 | |

| 1997 | 27649.87 | 28094 | Asian Financial Crisis |

| 1998 | 27895.21 | 28353 | |

| 1999 | 29246.91 | 28609 | |

| 2000 | 30014.60 | 28863 | |

| 2001 | 30161.13 | 29115 | |

| 2002 | 30323.97 | 29364 | |

| 2003 | 30323.97 | 29611 | Strong Republic Nautical Highway opens |

| 2004 | 30323.97 | 29856 | |

| 2005 | 28951.70 | 30098 | |

| 2006 | 29208.26 | 30338 | |

| 2007 | 29369.70 | 30574 | |

| 2008 | 29650.36 | 30809 | |

| 2009 | 29898.09 | 31040 | |

| 2010 | 31242.38 | 31269 | |

| 2011 | 31359.12 | 31495 | |

| 2012 | 31597.68 | 31718 | |

| 2013 | 32226.93 | 31939 | |

| 2014 | 32526.50 | 32156 | |

| 2015 | 32633.37 | 32371 | |

| 2016 | 32770.27 | 32583 | |

| 2017 | 32868.06 | 32792 | |

| 2018 | 32932.71 | 32998 | DPWH Department Order No. 133 takes effect |

| 2019 | 33018.25 | 33201 | |

| 2020 | 33119.57 | 33401 | |

| 2021 | 33212.62 | 33599 | |

| 2022 | 34352.40 | 33793 | |

| 2023 | 35164.13 | 33984 |

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Department of Public Works and Highways (2023). 2022 DPWH ATLAS. Retrieved February 28, 2024, from https://www.dpwh.gov.ph/dpwh/DPWH_ATLAS/index.htm

- ↑ Amano, N. (n.d.). Archaeological and historical insights into the ecological impacts of pre-colonial and colonial introductions into the Philippine Archipelago. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683620941152

- ↑ Tabunan, M. L. (2022). Heritage on the Ground: A Thirdspace Reading of Calle Crisologo, Vigan City, Philippines. Heritage & Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159032X.2022.2126233

- ↑ Ryder, T. (1976). The Carriage Journal: Vol. 14 No. 1 Summer 1976. Carriage Assoc. of America. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=mk88DwAAQBAJ

- ↑ a b c Department of Public Works and Highways. (n.d.). History. Retrieved February 26, 2024, from https://www.dpwh.gov.ph/dpwh/about/history

- ↑ Inflation Calculator | Find US Dollar’s Value From 1913-2024. (2024, February 13). https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/

- ↑ Department of Public Works and Highways (2022). Philippine National Road Network. Retrieved February 28, 2024, from https://www.dpwh.gov.ph/dpwh/DPWH_ATLAS/06%20Road%20WriteUp%202022.pdf

- ↑ Executive Order No. 483, s. 1951 | GOVPH. (1951, November 6). Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1951/11/06/executive-order-no-483-s-1951/

- ↑ Republic Act No. 917 | GOVPH. (1953, June 20). Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1953/06/20/republic-act-no-917/

- ↑ Executive Order No. 113, s. 1955 | GOVPH. (1955, May 2). Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1955/05/02/executive-order-no-113-s-1955/

- ↑ Republic Act No. 1192 | Senate of the Philippines Legislative Reference Bureau. (n.d.). Retrieved March 1, 2024, from https://issuances-library.senate.gov.ph/legislative%2Bissuances/Republic%20Act%20No.%201192

- ↑ Diosdado Macapagal, Fourth State of the Nation Address, January 25, 1965 | GOVPH. (1965, January 25). Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1965/01/25/diosdado-macapagal-fourth-state-of-the-nation-address-january-25-1965/

- ↑ Cabral, M. C. E. (2013). Asian Highway 26 (AH 26). https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/Philippines_0.pdf

- ↑ Philippine Development Plan, 1978-1982. (1978). National Economic and Development Authority. https://pdp.neda.gov.ph/devt-plans/

- ↑ Department of Public Works and Highways. (n.d.). History. Retrieved February 26, 2024, from https://www.dpwh.gov.ph/dpwh/about/history

- ↑ ABS-CBN News. (2018). The best of times? Data debunk Marcos’s economic ‘golden years’. Retrieved March 1, 2024, from https://web.archive.org/web/20181103210619/https://news.abs-cbn.com/business/09/21/17/the-best-of-times-data-debunk-marcoss-economic-golden-years

- ↑ Department of Public Works and Highways. (n.d.). History. Retrieved February 26, 2024, from https://www.dpwh.gov.ph/dpwh/about/history

- ↑ Philippine Development Plan, 1983-1987. (1983). National Economic and Development Authority. https://pdp.neda.gov.ph/devt-plans/

- ↑ Philippine Development Plan, 1987-1992. (1987). National Economic and Development Authority. https://pdp.neda.gov.ph/devt-plans/

- ↑ Philippine Development Plan, 1993-1998. (1993). National Economic and Development Authority. https://pdp.neda.gov.ph/devt-plans/

- ↑ Philippine Development Plan, 1999-2004. (2000). National Economic and Development Authority. https://pdp.neda.gov.ph/devt-plans/

- ↑ Philippine Development Plan, 2004-2010. (2004). National Economic and Development Authority. https://pdp.neda.gov.ph/devt-plans/

- ↑ Department of Public Works and Highways (2018). Department Order No. 133, Series of 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2024, from https://www.dpwh.gov.ph/dpwh/sites/default/files/issuances/DO_133_s2018.pdf

- ↑ Philippine Development Plan, 2017-2022. (2017). National Economic and Development Authority. https://pdp.neda.gov.ph/devt-plans/

- ↑ Philippine Development Plan, 2023-2028. (2023). National Economic and Development Authority. https://pdp.neda.gov.ph/devt-plans/

- ↑ DPWH ATLAS. (n.d.). Retrieved February 29, 2024, from https://www.dpwh.gov.ph/dpwh/DPWH_ATLAS/index.htm

- ↑ Handbook of Philippine Statistics, 1903-1959 (p. 165). (1960). Bureau of Census and Statistics. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=gQg-AAAAYAAJ

![{\displaystyle {\displaystyle S(t)=K/[1+exp(-b(t-t_{i}))]}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0bbc2f1261fe1875f3d75beab8cea687e324e4b0)