History of video games/Print version/First Generation of Video Game Consoles

| This is the print version of History of video games You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

- First Generation of Video Game Consoles

The First of Generations

[edit | edit source]Home game consoles as they are known today have to start somewhere and this is it. Though there are a number of definitions of which generation a console belongs to from here on out, most at least agree that the home consoles here belong to the first generation. After this definitions quickly get out of sync with each other Keep in mind that people classify game console generations as more of an art than a science, and there is no formal industry or academic organization which classifies consoles by their generation. While console generations are arbitrary, they still help with understanding consoles historically, so this book uses them.

Going forward in this book this book will generally share its console classification system with the system used by Wikipedia. This is because the system used by Wikipedia is widely used casually by the general public and news outlets. However it's important to note that this system is by no means the only one, and it definitely isn't the correct one in many academic contexts.

Trends

[edit | edit source]As stated previously, console generations are fairly arbitrary. However they aren't entirely baseless either. Besides time of release, generations are typically classified using factors such as the technologies used, social factors, economic conditions, and other influences. When a generation is mentioned in this book, prevailing industry movements will be brought up under Trends. Though these are not always universally true for a generation, they help give a big picture impression of what the industry valued at the time, and how things were changing.

The Bare Minimum

[edit | edit source]As an emerging technology, designers struggled to simply make an interactive device that plugs into a television, let alone design complex games for them. Systems this generation are often capable of drawing just a few lines or dots on a television screen, and little more. Systems often made more with less by asking players to attach overlays to their television sets, and other tricks to make the most out of limited hardware capabilities.

Features many would consider fundamental today, such as automatically keeping scores, are not a given and are frequently left for the player to keep track of. Other features such as color graphics, single player modes, and the ability for a console to generate even a simple beep for audio were sometimes included, but were by no means universal. Keep in mind that this console generation started less than two decades after the first consumer color television broadcast.[1] In fact, in 1972, when the Magnavox Odyssey kicked off the first generation of home video game consoles, Color Television adoption had only just reached over 50% in the United States of America,[2] and many important nations had yet to launch color TV broadcasts.[3]

Dedicated systems

[edit | edit source]Most first generation consoles were only able to play the games built into them, with the Magnavox Odyssey being the primary semi-exception by using jumper cards used to manipulate console internals for desired results.[4] Other consoles such as those in the PC-50x family, were simply adapters for cartridges which effectively contained the entire console. Proper cartridges used as game software media would not appear until the second generation with the Fairchild Channel F.[5]

Late in this generation, the industry also saw the first TV-Game console combination unit, in the 1977 ITT Schaub-Lorenz Programmable Television.[6][7] This trend of integrating consoles and displays would continue in following generations as a niche market.

Battery power

[edit | edit source]Most home game consoles this generation were powered by batteries, despite needing a television to play games. This reduced the upfront cost and complexity of the system because an AC adapter was not needed and consistent DC power would be supplied by the batteries. Some consoles did have an optional power adapter available for purchase.[8]

It is important to note that during the 1970's power supply technology was undergoing rapid advancements, and efficient switching power supplies were only starting to see adoption in consumer products by the end of the decade.[9]

Home Consoles

[edit | edit source]There were a staggering number of console in the first generation with over 900 models of them sold across the globe.[10] What's even more staggering is that most of them were based on standardized "pong on a chip" designs,[10] playing almost the exact same games as a result. Furthermore, the gaming industry is notoriously bad at preserving its history, and many of these consoles are known by little more than their names. Therefore this part of the book lists only the most notable among these multitude of consoles, for which substantial references still exist.

External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Google Arts and Culture - Early Home Gaming online exhibit.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Timeline Events in the History of Broadcasting". chip.web.ischool.illinois.edu. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ "Facts-Stats". web.archive.org. 31 July 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ "Timeline of the introduction of color television in countries". Wikipedia. 10 February 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ "Video Game Firsts: The First Home Video Game Console - The Magnavox Odyssey - Warped Factor - Words in the Key of Geek". www.warpedfactor.com. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ Edwards, Benj (22 January 2015). "The Untold Story Of The Invention Of The Game Cartridge". Fast Company. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ Manikas, Pantelis. "ITT Schaub-Lorenz Programmable Television". The voice of the gaming community. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ "ITT Schaub-Lorenz Programmable Television – The Video Game Kraken". Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ Voskuil, Geplaatst door Erik. "Nintendo Color TV-Game 6 (カラー テレビゲーム 6, 1977)". Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "A Half Century Ago, Better Transistors and Switching Regulators Revolutionized the Design of Computer Power Supplies". IEEE Spectrum: Technology, Engineering, and Science News. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ a b "List of first generation home video game consoles". Wikipedia. 14 January 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

-

An APF TV Fun model 401 being played on a CRT television.

History

[edit | edit source]

Background

[edit | edit source]Before making the APF TV Fun, APF made consumer electronics like calculators.[1]

Launch

[edit | edit source]The APF TV Fun model 401 was released in 1976 for $125.[2][3] The system sold very well with 400,000 first year sales,[4] and lead APF to make more game consoles.[3]

In February 1977, the TV Fun Model 405 was launched.[5]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]The APF-MP1000 followed the system, featuring much better capabilities and design.

Technology

[edit | edit source]Casing tended to be shared between models of APF TV Fun.[6] Systems were manufactured in Japan.[7]

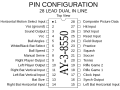

401

[edit | edit source]The APF model 401 uses a General Instrument AY-3-8500 chip, and takes 6 C type batteries.[2][3] A CD4071 chip handles video output on the APF model 401.[8]

402

[edit | edit source]The 402 also uses a General Instrument AY-3-8500 chip but has an additional General Instrument AY-3-8515 chip to add color graphics capability to the system.[9]

Notable games

[edit | edit source]The APF TV Fun 402 supported two light gun games.[9]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]APF TV Fun 402C console

[edit | edit source]APF TV Fun Controllers

[edit | edit source]-

Paddle controllers for the APF TV Fun 402C.

-

Light Gun for the APF TV Fun 402C.

APF TV Fun 402C Internals

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Old Computers - APF TV Fun 401.

- Pong Museum - APF TV Fun 401.

References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ "TheGameConsole.com: APF TV Fun Model 401 Game Console". www.thegameconsole.com. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e f "pongmuseum.com - APF TV Fun - Model 401". pongmuseum.com. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ Edwards, Benj (2 September 2016). "Ed Smith And The Imagination Machine: The Untold Story Of A Black Video Game Pioneer". Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/3063298/ed-smith-and-the-imagination-machine-the-untold-story-of-a-black-vid.

- ↑ "APF TV Fun model 405 retro gaming console". Vox Odyssey. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "APF TV Fun". Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "APF TV FUN 401". IT History Society. 15 December 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "APF TV Fun console repair". www.raphnet.net. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "APF TV Fun Consoles". AtariAge Forums. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

-

An Atari Game Brain. A few consoles are known to have been produced.

History

[edit | edit source]The Game Brain was developed by Atari as an early effort by the company to create a game console which used interchangeable cartridges.[1]

Development on the Atari Game Brain was discontinued before release in order to focus efforts on the Atari 2600, which featured a more advanced design.[2]

Technology

[edit | edit source]Each cartridge for the Game Brain essentially contained all major hardware for the console, essentially being condensed versions of previous Atari dedicated consoles.[2]

The use of 4 rounded buttons arranged in cardinal directions is considered a precursor of sorts to the later D-Pad design.[3]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]-

On display at E3 2011.

-

On display at E3 2011.

External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Atari Museum - Game Brain Page with history and photographs.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Atari Game Brain - Ultimate Console Database". ultimateconsoledatabase.com. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ↑ a b "The Atari Game Brain (C-700)". www.atarimuseum.com. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ↑ Venables, Michael. "Adam Coe's Modded Future: Eco-Friendly, Ergo-Friendly, Evil D-Pads And White Zombies" (in en). Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaelvenables/2013/07/07/adam-coes-modded-future-eco-friendly-ergo-friendly-evil-d-pads-white-zombies/?sh=52dccfb45641.

-

The BSS 01 console from East Germany.

History

[edit | edit source]Development

[edit | edit source]

The system used imported chips from the United States of America, a rare occurrence due to the prevalence of clone chips and serious export restrictions on legal transport of such chips to communist nations.[1][2][3] These chips were likely obtained by funneling them through a network of fake companies to hide their use from export regulations and then smuggled across the border to East Germany.[4]

Launch

[edit | edit source]The BildSchirmSpiel 01 (BSS 01) was released sometime around 1980 in East Germany for 500 East German marks, playing games similar to Pong.[2][3] This cost of the console was prohibitive, costing as much as a worker would make in a half month.[1]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]

The price was reduced to 330 East German Marks in 1984, when the system was discontinued having sold 1,000 consoles, in order to focus production on alarm clocks with radios.[5][1][6]

Around the reunification of East Germany with West Germany in 1990, most East German computer organizations folded.[7] This included the BSS 01 manufacturer Halbleiterwerk Frankfurt Oder (HFO), which ceased operations around 1991.[8] Despite widespread unemployment initially, the computer industry had returned to former East German areas by 2000.[9][7]

Retrospective

[edit | edit source]The BSS 01 serves as a unique example of how a Warsaw Pact country approached building a video game console during the Cold War, and the barriers that had to be surmounted to create it. It furthermore shows how social factors surrounding the release of a console could cause it to sell poorly, in this case a high cost compared to standard worker wages.

Technology

[edit | edit source]The BSS 01 uses a GI AY-3-8500-7 chip and produces black and white graphics.[2]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Old Computers - BSS 01 page with history and specs.

- Pong Museum - BSS 01 page with history, photos, and specs.

- Game Medium - BSS 01 page with history.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c "pongmuseum.com - and the ball was square... RFT - TV Spiel BSS 01 made in DDR - GDR". pongmuseum.com. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "Gaming Beyond the Iron Curtain: East Germany". Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "Retropolis #104: Piep-Show jenseits der Mauer - BSS 01". Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "BSS 01". Wikipedia. 11 November 2020. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ↑ "BSS 01 / Bildschirmspiel 01 - DDR Konsole - OhrBIT (04.06.2017)". Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ a b Schmid, John; Tribune, International Herald (13 March 2002). "East German chip zone is growing despite global slowdown : Silicon Saxony dodges crisis (Published 2002)". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "East German CPU's The CPU Shack Museum". Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ McGrane, Sally (25 October 2000). "ONLINE OVERSEAS; Their Roots Give Former East Germans an Edge (Published 2000)". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ Markham, James M. (13 February 1984). "TV BRINGS WESTERN CULTURE TO EAST GERMANY (Published 1984)". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

-

The original Coleco Telstar.

History

[edit | edit source]

Development

[edit | edit source]Coleco was founded as the Connecticut Leather Company in west Hartford Connecticut in 1932 by Maurice Greenberg, a Russian immigrant.[1][2]

The Coleco Telstar was devised as a home version of Pong in 1975.[1] Shortly after product design began, Leonard Greenberg of Coleco discovered that home pong style games already existed.[1]

Much of the Coleco Telstar had to be redesigned in a week to meet an FCC deadline, after they failed their first FCC compliance test.[3][4] Coleco quickly signed a licensing agreement with Magnavox to consult with Ralph Baer, who successfully got the radio interference of the Telstar under control.[3]

At least some units were made in the United States of America.[5]

Launch

[edit | edit source]

The first Coleco Telstar console was released in 1976 at a cost of $50 with the capability of playing Hockey, Tennis, and Handball.[6] In 1976 over a million Coleco Telstars sold due to it's low price, which was about half of what competitors charged.[6][1] Still sales were considerably hampered by a strike and material shortage at the critical lead up to the 1977 Christmas season.[7]

In 1977 the Coleco Telstar deluxe was released exclusively for the Canadian market.[8]

The Coleco Telstar consoles were followed by the ColecoVision.

Technology

[edit | edit source]The original Coleco Telstar used a General Instrument AY-3-8500.[6] This inexpensive chip contained the game logic and graphical output functions.[9]

The Telstar Arcade uses a very different triangle cartridge based system with each cartridge containing a MOS MPS 7600 processor,[10][11] as well as game ROM.[12] This cartridge based approach is completely different from every other Coleco Telstar console, which were dedicated consoles. However the console still shared the Telstar brand.

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Telstar Series

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Old Computers Museum - Coleco Telstar page with history and specs.

- Pong Story - Coleco Telstar page with history and photos.

- Video Game Console Library - Coleco Telstar page with history, specs, and photos.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c d Kleinfield, N. R. (21 July 1985). "COLECO MOVES OUT OF THE CABBAGE PATCH (Published 1985)". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ↑ "Coleco Industries". Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ↑ a b "Pong-Story : Coleco Telstar". www.pong-story.com. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ "Because of Her Story". Because of Her Story. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ "Video game console:Coleco Telstar Ranger - Coleco Industries". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ↑ a b c "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ "COLECO'S NEW VIDEO CHALLENGE (Published 1982)". The New York Times. 11 November 1982. https://www.nytimes.com/1982/11/11/business/coleco-s-new-video-challenge.html.

- ↑ "Coleco Canada – Montreal Video Game Museum". Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ↑ "Pong-Story : PONG in a Chip". www.pong-story.com. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ "This Is the Strangest Video Game Console of All Time - IGN". Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ↑ "Pong-Story : Coleco Telstar Arcade". www.pong-story.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "Coleco Telstar Arcade (1977 – 1978)". Museum of Obsolete Media. 14 May 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

-

A Nintendo Computer TV Game console

History

[edit | edit source]Development

[edit | edit source]Nintendo licensed the Odyssey technology from Magnavox to produce the Color TV Game 6 and Color TV Game 15.[1] Noted engineer Masayuki Uemura assisted in the development of Color TV-Game systems.[2]

Launch

[edit | edit source]

Released in 1977, the Color TV-Game line were the first consoles released by Nintendo, starting with the Color TV Game 6.[3]

The Color TV Game 15 was released in 1978 at a cost of 15,000 yen.[3][4]

The Color TV Game Racing 112 had the worst market performance of the Color-TV-Game series.[5] The price of this system was cut multiple times.[6]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]350,000 Color TV Game 6 consolers were sold, but were not profitable due to high production costs.[3][7] The complete Color TV game series sold about three million consoles.[8]

The Color TV-Game was succeeded by the cartridge based Nintendo Entertainment System and Famicom, which featured much improved capabilities over the Color TV Game line.

Technology

[edit | edit source]Models of the Color TV Game 6 used 6 C type batteries as a power source, with an optional power adapter being available for the CTG-6V model.[9]

Often Japanese televisions of the 1970's were not capable of easily accepting an input from consumer hardware, so the Color TV-Game line was designed with this in mind.[10]

Notable games

[edit | edit source]The Color TV-Game 6 and 15 both shared their primary Mitsubishi integrated circuit, with the Color TV-Game 15 exposing 9 more games then the Color TV-Game 6.[11]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Color TV Game Variants

[edit | edit source]Blockbreaker Kuzushi

[edit | edit source]Blockbreaker Kuzushi Internals

[edit | edit source]-

The ribbon cable loops underneath the motherboard to the front panel.

-

A top down view of the Color TV Game. The large Mitsubishi M58821P 9592 chip can be seen.

Origin of Nintendo

[edit | edit source]Nintendo was founded in Kyoto, Japan in 1889 to make Hanafuda cards,[12] making it one of the oldest companies to have a major impact on the video game industry.

-

Nintendo's first headquarters in Kyoto, Japan - 1889.

-

1890 poster showing Nintendo playing cards.

-

Nintendo Staff in 1949.

External References

[edit | edit source]- Centre for Computing History - Color TV Game 6 page.

- Centre for Computing History - Color TV Game 15 page

- Before Mario - Color TV Game series page.

- Gamester81 - Color TV Game history, model info, and trivia page.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Persuasive Games: Wii Can't Go On, Wii'll Go On" (in en). www.gamasutra.com. https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/182294/persuasive_games_wii_cant_go_on_.php. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ "Masayuki Uemura, the designer of the NES and SNES, has died age 78". VGC. 9 December 2021. https://www.videogameschronicle.com/news/masayuki-uemura-the-designer-of-the-nes-and-snes-has-died-age-78/.

- ↑ a b c "Nintendo's First Console Is One You've Never Played" (in en-us). Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/nintendos-first-console-is-one-youve-never-played-5785568. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ Voskuil, Geplaatst door Erik. "Nintendo Color TV Game 15 - Service Manual (カラー テレビゲーム 15 サービス マニュアル)". Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ "Designing the Nintendo Entertainment System - Masayuki Uemura talk". JUICY GAME REVIEWS. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ Voskuil, Geplaatst door Erik. "Nintendo Color TV Game Racing 112 (任天堂 カラー テレビゲーム レーシング 112, 1978)". Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ "Looking Back at Nintendo's Forgotten Console". CBR. 26 April 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ↑ "Color TV Game 6 - Game Console - Computing History". www.computinghistory.org.uk. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ Voskuil, Geplaatst door Erik. "Nintendo Color TV-Game 6 (カラー テレビゲーム 6, 1977)". http://blog.beforemario.com/2011/04/nintendo-color-tv-game-6-6-1977.html. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ O'Kane, Sean (18 October 2015). "7 things I learned from the designer of the NES". The Verge. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ Voskuil, Geplaatst door Erik. "Nintendo Color TV-Game 15 (カラー テレビゲーム 15, 1977)". Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ "Video game:Nintendo Color TV Game 6 - Nintendo". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

-

The 1972 Electro Tic-Tac-Toe by Waco.

History

[edit | edit source]The Waco Electro Tic-Tac-Toe was released in 1972.[1][2] The Waco Electro Tic-Tac-Toe is perhaps among the first electric handheld systems and a possible influence to many other designs that would follow, though it's reliance on players for logic and scoring makes this status disputed.[3][1] Unfortunately, little more is known about the history of the Waco Electro Tic-Tac-Toe.

Technology

[edit | edit source]Button illumination came from lamps, with filters used to add color.[1] The system was simple, and gameplay only supported two players.[1] The Electro Tic-Tac-Toe is powered by two D size batteries.[4]

-

A small incandescent bulb used for Christmas tree lighting. In the early 1970's small bulbs like this served the role more efficient LED's would later serve, including in the Electro Tic-Tac-Toe.

-

Two D cell batteries, similar to those used in the Electro Tic-Tac-Toe. These large alkaline batteries were standardized and could commonly be found in stores. These batteries were not typically integral in devices, and could be changed on the fly, but this was because these batteries were one use only and not meant to be rechargeable. A match stick is included for scale.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c d "Waco Electro Tic-Tac-Toe - First Electronic Game Ever?". Retro Thing. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ↑ "Games". www.decodesystems.com. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ↑ "Evolution of handheld gaming devices. timeline". Timetoast. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "Waco Tic-Tac-Toe". www.handheldmuseum.com. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

History

[edit | edit source]

Entex was founded in Compton, California in 1970 to produce toys.[1] Entex launched the Gameroom Tele-Pong in 1976,[2][3] becoming an early entrant into the game console market. Little more information is available for this console, though it's earliness and following Entex consoles make it noteworthy.

Technology

[edit | edit source]The Gameroom Tele-Pong likely used analog circuits,[4] similar to the Magnavox Odyssey. The system uses eight integrated circuits, and 26 transistors.[5][3] The console has a one player mode, which is known for its high difficulty.[2][3]

The Gameroom Tele-Pong is powered by four C type batteries.[4] Players may manually turn score dials on the console to track scores.[3] This was common feature on consoles lacking major compute resources, as it removes the need for players to manually track score in their heads or on paper.

External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Old Computers Museum - Entex Gameroom Tele-Pong page with photo.

- Old Computers Museum - Binatone TV Game page with photo.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Entex Handheld Games". handheldmuseum.com. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ↑ a b "Entex Gameroom Tele-Pong is a video game console". Vox Odyssey. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c d Manikas, Pantelis. "Entex Gameroom Tele-Pong". News & Reviews for Videogames & Gaming Consoles consall.eu. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ↑ a b "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ↑ "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

-

The Magnavox Odyssey and controller.

History

[edit | edit source]Background

[edit | edit source]

The Magnavox company was founded on the 5th of July in 1917, and mainly produced products such as radios, speakers, and televisions for consumers and the military.[1]

Ralph Baer was born in 1922 in Germany, where he was soon denied an education under the increasing power of the Nazis.[2] Baer and his family fled to the United States as refugees, fleeing persecution in Nazi Germany.[3] A chance encounter on a subway in 1938 lead Baer to gain an interest in technology.[4] Baer later was drafted into the American army to fight the Nazis in World War II.[5][3]

Development

[edit | edit source]

Ralph Baer, now an engineer who specialized in television, thought of an interactive television game in 1966.[6] In 1967 a prototype unit called TV Game Unit #1, which allowed a dot to be manipulated on a television screen.[6] This test system used vacuum tubes instead of transistors, but was still compact due to its simplicity.[7]

The following prototype TV Game Unit #2 allowed for two players, and was referred as the "Pump Unit" because of its unique up and down handle controller.[8]

Baer convinced company leadership to fund his project with a $2000 budget.[9] The TV Game Unit #7 prototype, called the "Brown Box" could play multiple games, and had two controllers with a design that, while unrefined, was quite similar to the gamepads used in the third and fourth generation of consoles.[10] A prototype 1968 controller featuring a real golf ball on the end of a sturdy joystick was made, allowing the use of a standard golf club to be used in a golf game.[11] A prototype plastic lightgun was also made for shooting games.[12] Program card overlays served as a sort of game medium, indicating which switches needed to be pressed to access specific games. [13]

Magnavox contracted Nintendo, then a Japanese company that made a number of consumer goods including toys, to produce the light guns for the Magnavox Odyssey in 1971, adapting an existing Nintendo light gun toy for this purpose.[14][15][16]

On January the 27th, 1972 production of the Magnavox Odyssey began.[17]

The name Odyssey was chosen as a nod to the Stanley Kubrick film 2001: A Space Odyssey.[18]

Launch

[edit | edit source]Magnavox launched the Magnavox Odyssey in May of 1972.[6][17] The cost of the Odyssey was $99.95,[18] which included 12 pack in games.[19]

For reasons unrelated to the Odyssey, Dutch company Philips acquired the American company Magnavox in 1974.[20][1] The Philips company was founded in 1891, making it among the oldest companies to have a large involvement in the gaming industry.[21][22]

The Magnavox Odyssey 100 was released in 1975, with used four integrated circuits to greatly simplify hardware.[23]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]Production of the Magnavox Odyssey ended in 1975.[24] The console was followed by the Odyssey series of dedicated consoles. The console would later receive a proper followup in the Magnavox Odyssey².

The Magnavox Odyssey sold less than 100,000 consoles its first year and about 350,000 total[25] due to poor marketing.[6] Magnavox salespeople would often incorrectly imply that a Magnavox Television was required to use the console to sell more Magnavox televisions, despite it's compatibility with nearly all televisions.[26][27]

The Magnavox Odyssey would inspire Atari co-founder Nolan Bushnell to have his company make Pong, eventually leading Magnavox to take legal action against Atari.[27][28]

In 1973, following the launch of the Odyssey, Baer demonstrated a concept All Purpose Box console pioneered a number of concepts which are now common.[29] The Multimedia Box would run games, including some which could be advertiser supported, educational content, and mail order shopping.[29]

In 2021 Handball for the Brown Box prototype would be the first video game to be depicted on currency produced by the United States Mint.[30]

Because it is commonly recognized as the first home game console, the Magnavox Odyssey is also nearly universally categorized as a first generation console.

Preservation

[edit | edit source]Due to it's wildly different technical architecture, and a reliance on physical objects, accurate emulation of the Odyssey relies on much different techniques compared to standard emulators.

In 2017 a team at the University of Pittsburgh began working to preserve Odyssey related materials.[31]

Technology

[edit | edit source]

The Magnavox Odyssey lacked a computer, instead using analog circuitry and game cards that manipulate internal jumpers to achieve desired results.[32][33] Display output was limited to a line and three white blocks[27], so color overlays and physical items were used to enhance gameplay.[34] Overlays attached to the CRT televisions via either the static electricity generated by the television, or manually with tape.[35]

The system is powered by six C type batteries.[36], though an optional AC adapter was available.[37] Inserting a game card turned on the power, so the unit lacks a power button.[38]

Games

[edit | edit source]Because the Odyssey lacked a computer, and was primarily a graphics generating device, games for the Magnavox Odyssey were simple, and were often versions of real sports like tennis.[39] Other games included a US Geography quiz game, and a roulette game.[39] No matter the game, the Odyssey relies a lot on its players to use their imaginations, as well do things like keep score or enforce rules.

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Console

[edit | edit source]Controller

[edit | edit source]-

Controller front. The single stage vertical dial is visible.

-

Controller back and twelve pin plug. The two stage horizontal and "English" dial is visible.

Accessories

[edit | edit source]Technology

[edit | edit source]Marketing

[edit | edit source]

External Resources

[edit | edit source]- MoMA - Magnavox Odyssey exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art.

- Smithsonian National Museum of American History - Magnavox Odyssey page featuring photo with Odyssey and packaging.

- Smithsonian National Museum of American History - Article about Ralph Baer and prototypes.

- Video Game Console Library - Magnavox Odyssey page with history and photos.

- Old Computers - Magnavox Odyssey Page with history and technical information.

- Centre for Computing History - Magnavox Odyssey page

- Video Game Kraken - Odyssey by Magnavox page

- Pong Story's website on the Odyssey.

- Video Game History Foundation - Page on the Odyssey focusing on the history of advertising the system.

- BBC Archive - Includes a video from 1973 which introduces the then novel concept of a video game.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "Because of Her Story". Because of Her Story. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "Inventor Ralph Baer Was An American Success Story". NPR.org. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ Sullivan, Gail. "The 1938 subway ride that led to the invention of video games". Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2014/12/08/the-subway-ride-that-led-to-the-invention-of-video-games/.

- ↑ "Motherboard TV: Oral History of Gaming: Ralph Baer and his All-Purpose Boxes". www.vice.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c d "Video Game History". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "TV Game Unit #1, 1967". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "The Pump Unit, 1967". National Museum of American History. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "Early Home Video Game History: Making Television Play - The Strong National Museum of Play". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ "The Brown Box, 1967–68". National Museum of American History. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "The Brown Box Golf Game Accessory, 1968". National Museum of American History. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "The Brown Box Lightgun, 1967–68". National Museum of American History. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "The Brown Box Program Cards, 1967–68". National Museum of American History. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "Nude Clan: A Video Game Podcast". nudeclan.libsyn.com. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ↑ "Nintendo: the history behind the gaming pioneers". Maxxor Blog. 29 July 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ↑ Voskuil, Geplaatst door Erik. "Nintendo Light-beam games Kôsenjû SP and Kôsenjû Custom (光線銃SP, 光線銃 カスタム 1970-1976)". Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ↑ a b "Magnavox Odyssey - First Home Video Game System in 1972". www.cedmagic.com. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ a b Range, Peter Ross (15 September 1974). "The space age pinball machine (Published 1974)". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ↑ "Inside the Magnavox Odyssey, the First Video Game Console" (in en). PCWorld. 27 May 2012. https://www.pcworld.com/article/256101/inside_the_magnavox_odyssey_the_first_video_game_console.html. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ Koshetz, Herbert (29 August 1974). "North American Phillips Seeks Magnavox Shares (Published 1974)". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1974/08/29/archives/north-american-phillips-seeks-magnavox-shares-an-offer-is-made-for.html. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "Our heritage - Company - About". Philips. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "Philips CD-i Retro Gamer". www.retrogamer.net. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "Magnavox Odyssey 100 Teardown". iFixit. 30 August 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "Video game:Magnavox Odyssey 2 The Voice Series Sid the Sepllbinder - Magnavox Company". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ "From Wind-Up Dolls to Handheld Computers, Toys Follow Evolution of Tech". Smithsonian Insider. 21 December 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "Magnavox Odyssey Video Game Unit, 1972". National Museum of American History. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c "A Video Game Odyssey: How Magnavox Launched The Console Industry". Hackaday. 14 September 2017. https://hackaday.com/2017/09/14/retrotectacular-a-video-game-odyssey/. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ Wawro, Alex. "Looking back at one of the very first video game rivalries" (in en). www.gamasutra.com. https://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/233898/Looking_back_at_one_of_the_very_first_video_game_rivalries.php. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ a b Cifaldi, Frank. "Video game inventor demonstrates multimedia box...in 1973" (in en). www.gamasutra.com. https://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/175505/Video_game_inventor_demonstrates_multimedia_boxin_1973.php. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ Bulfinch, Chris (11 June 2021). "Coin Honors Inventor and the Birth of Videogame Culture". CoinWeek. https://coinweek.com/modern-coins/coin-honors-inventor-and-the-birth-of-video-game-culture/.

- ↑ "It was a financial dud, but the first video game console, the Magnavox Odyssey, may be getting a new life" (in en). Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. https://www.post-gazette.com/business/tech-news/2019/02/24/magnavox-odysssey-pitt-vibrant-media-lab-fortnite-juju-smith-schuster-steelers-video-games/stories/201902170007.

- ↑ "Inside the Magnavox Odyssey, the First Video Game Console". PCWorld. 27 May 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "It was a financial dud, but the first video game console, the Magnavox Odyssey, may be getting a new life" (in en). Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. https://www.post-gazette.com/business/tech-news/2019/02/24/magnavox-odysssey-pitt-vibrant-media-lab-fortnite-juju-smith-schuster-steelers-video-games/stories/201902170007. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "Magnavox Odyssey Video Game Unit, 1972". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "In Search of the First Video Game Commercial". Video Game History Foundation. 10 January 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ↑ "Inside the Magnavox Odyssey, the First Video Game Console" (in en). PCWorld. 27 May 2012. https://www.pcworld.com/article/256101/inside_the_magnavox_odyssey_the_first_video_game_console.html#slide6. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "Inside the Magnavox Odyssey, the First Video Game Console". PCWorld. 27 May 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "Inside the Magnavox Odyssey, the First Video Game Console". PCWorld. 27 May 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ a b Cifaldi, Frank. "Happy 40th birthday, video games" (in en). www.gamasutra.com. https://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/176677/Happy_40th_birthday_video_games.php. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

-

Merlin playing a game of Magic Square.

History

[edit | edit source]

Development

[edit | edit source]The Merlin was developed by former NASA employee Dr. Bob Doyle and his astrophysicist wife Dr. Holly Doyle in the 1970's.[2][3][4] In 1977 Bob Doyle was working on an electronic tic tac toe game, but was told by a marketing employee to make something that wasn't boring.[5] The case was designed by Arthur Venditti, who had also named the Nerf Ball.[5][6]

Speaking to Washington Post reporter Tom Zito in 1978, Robert Doyle lamented not having long term storage for the Merlin due to the limitations of technology at the time.[7] Doyle also hoped to use voice activated technology in the future.[7] Reporter Tom Zito himself would later work on the Control Vision console.[8]

Launch

[edit | edit source]The Merlin was launched by Parker Brothers in 1978.[3] The Merlin cost $25 dollars[9] or $35 dollars.[10] In 1979 the Merlin continued to sell well.[11]

In 1982 the Master Merlin was launched.[12] In 1996 the screen based system Merlin, the 10th quest was released.[13] A smaller, more power efficient Merlin was released in 2004.[14]

Technology

[edit | edit source]The Merlin is powered by a 4 bit Texas Instruments TMS1100 processor.[5][15][16] When ordered in bulk, the TMS1000 was inexpensive, and cost around $2.[17]

The Merlin has 48 bytes of RAM and two kilobytes of ROM.[7][5]

System Gallery

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Centre for Computing History - Merlin the Electronic Wizard page.

- Computer History Museum - Merlin page.

- Handheld Museum - Merlin page.

- Handheld Museum - Master Merlin page.

- Handheld Museum - Merlin the 10th quest page.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Forman, Ethan. "Brokers look to reposition former Parker Brothers building". Salem News. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ↑ Datamation. Technical Publishing Company. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ a b "Handheld video game:Merlin: The Electronic Wizard - Parker Brothers". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ↑ Thompson, Jacqueline. Future Rich: The People, Companies, and Industries Creating America's Next Fortunes. W. Morrow. ISBN 978-0-688-04039-0. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ a b c d "Xconomy: Bob Doyle and the Magic of Merlin, the First Mobile Game - Page 2 of 2". Xconomy. 28 February 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "Obituary of Arthur Venditti Conway, Cahill-Brodeur Funeral Homes". ccbfuneral.com. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c Zito, Tom (19 December 1978). "Wired-Up Wizards". Washington Post. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ Noble, Barbara Presley (20 December 1992). "At Work; Here's a Switch -- Keep the Job (Published 1992)". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "Interview: Ben Herman, former SNK Playmore USA president". Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ↑ The Washingtonian. Washington Magazine, Incorporated. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ New Products and Processes. Newsweek, Incorporated. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ Muir, John Kenneth (2 September 2016). "The Electronic Wizard: Remembering MERLIN (Parker Bros; 1978)". Flashbak. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "Parker Brothers Merlin, The 10th Quest". www.handheldmuseum.com. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ S, Scott. "Milton Bradley's Merlin:The Electronic Wizard". Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "Dave From EEVBlog Takes A Look At The Merlin Game From 1978!". Xadara. 7 August 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "The TMS1000: The First Commercially Available Microcontroller". Hackaday. 18 February 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ↑ "The Chip Collection - STATE OF THE ART - Smithsonian Institution". smithsonianchips.si.edu. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

-

The Odyssey 300

History

[edit | edit source]The Odyssey series was a follow up to the original Magnavox Odyssey console made following the acquisition of Magnavox by Philips in 1974.[1][2] This series of consoles began to be released in 1975 as cheaper dedicated consoles with built in games, as opposed to the original Odyssey's ability to play multiple games via jumper cards.[3][4] Unlike the original Odyssey which attempted to offer games from sports to a haunted mansion, Odyssey series consoles stuck to popular sports games.

The last Magnavox Odyssey series consoles were released in 1977[4] and the last Philips Odyssey console was released in 1978.[5] The Odyssey series of consoles were followed by the Magnavox Odyssey², a far more capable console capable of running software on cartridges.

Models

[edit | edit source]As more models were released, significant technical improvements were made, though these improvements were mostly iterative rather than groundbreaking.

Magnavox Odyssey 100

[edit | edit source]The Magnavox Odyssey 100 was released in 1975.[6] The system was built in the USA with a simple single layer circuit board and four Texas Instruments integrated circuits.[6] Uniquely, the system uses cardboard shielding internally,[6] instead of more durable materials or materials that offered improved radio frequency properties. The system can play either Tennis or Hockey and can generate sound,[7] a notable feature which was not a given in video games at the time.

Magnavox Odyssey 300

[edit | edit source]The 1976 Odyssey 300 offered an improved experience with the ability to display game scores on screen.[8] Previously scorekeeping on Odyssey consoles had been an exercise left to the player.

A different version of the Odyssey 300 that was built into a television set was also sold.[9] This was part of a small trend aimed at a niche market where specific models of television sets were integrated with a specific model of game console, typically for the purpose of saving space, making setup easier, or adding a sales point to a television model at the cost of increased expense and lower reliability.

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Consoles

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Pong Story - Contains history, console photos, box art, and screenshots for the Odyssey series.

- Old Computers Museum - Odyssey 100 article.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "The Ultimate Odyssey^2 and Odyssey^3 FAQ". web.archive.org. 8 March 2008. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ↑ Koshetz, Herbert (29 August 1974). "North American Phillips Seeks Magnavox Shares (Published 1974)". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1974/08/29/archives/north-american-phillips-seeks-magnavox-shares-an-offer-is-made-for.html.

- ↑ "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ↑ a b "Narrative and Milestones". Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ↑ "Pong-Story: Other Magnavox Odyssey systems". www.pong-story.com. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ↑ Henzel, Matthew. "Magnavox Odyssey 100 @ Video Game Obsession". www.videogameobsession.com. Video Game Obsession. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ↑ "TheGameConsole.com: Magnavox Odyssey 100 Game Console". www.thegameconsole.com. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ↑ "7 Classic Game Consoles Built Into TV Sets" (in en). PCMAG. https://www.pcmag.com/news/7-classic-game-consoles-built-into-tv-sets.

-

The Prinztronic tournament colour programmable 2000, a member of the PC-50x Family.

History

[edit | edit source]

The first PC-50X console was released in 1975.[1][2] The system was designed to be low cost,[3] and over two hundred variants of based on the PC-50X design were made.[1]

The PC-50x Family petered out over the course of the 1980's.[1][2]

Technology

[edit | edit source]PC-50X consoles made use of various General Instrument chips housed in cartridges[1], essentially making these pong consoles in cartridges, with the console simply being a power supply and interface for controllers and the television.[4] Cartridges held as many as 10 variations of a game.[5]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Console Variants

[edit | edit source]Cartridges

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Video Game Console Library - Page containing photos of different models.

- 20th Century Video Games - Page containing photos and origin of various models.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c d "PC50X Family". Video Game Console Library. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "Prinztronic Tournament 5000 - Game Console - Computing History". www.computinghistory.org.uk. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ↑ "The PC-50x Family games and game console information". Vox Odyssey. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ↑ "Cole's Nerd-stuff Blog". nerdstuffbycole.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ↑ "General Instrument PC-50x cartridge (1977 - early 1980s)". Museum of Obsolete Media. 10 August 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

History

[edit | edit source]Due to the popularity of Pong as an arcade game, a number of official and clone consoles were made to play Pong and similar games at home. While some of these were officially licensed, and while some simply played a number of built in sports games, these first generation dedicated consoles are commonly simply referred to as "Pong Clones".

A notable early attempt at a home pong console was the 1974 release of the Video Action II.[1][2] However it would be Atari's own release of Home Pong in 1975 that would help popularize the model of dedicated home video game consoles.[3][4]

While many of these are well documented, there are many examples, potentially with interesting history of their own, that are not well documented. This page catalogues these consoles, should they be of interest. In particular, a number of consoles from the Eastern Bloc feature innovative or unique designs not seen in the Western Bloc and non aligned countries.

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Eastern Bloc Consoles

[edit | edit source]-

Турнир, an example of a dedicated pong console from the Soviet Union.

Эврика

[edit | edit source]-

Эврика (Eureka) console from the Soviet Union with controllers deployed.

-

Эврика (Eureka) with controllers stowed.

Электроника Экси-Видео 01

[edit | edit source]Видеоспорт-М

[edit | edit source]-

Видеоспорт-М

Videosport 3

[edit | edit source]Other Consoles

[edit | edit source]-

Sears TeleGames Pong, an officially licensed pong console.

-

Tomy Blip, an electromechanical self contained pong console that used LEDs instead of a screen.

-

Videomaster Rally

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Smith, Keith (3 November 2013). "The Golden Age Arcade Historian: URL's Video Action - The First US Consumer Video Game after Odyssey?". The Golden Age Arcade Historian. https://allincolorforaquarter.blogspot.com/2013/11/urls-video-action-first-us-consumer.html.

- ↑ "Video Action II by Universal Research Laboratories – The Video Game Kraken". Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ "Atari Home Pong". www.atarimuseum.com. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ "Atari PONG - Game Console - Computing History". www.computinghistory.org.uk. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

-

The Epoch TV Tennis Electrotennis

History

[edit | edit source]

Launch

[edit | edit source]TV Tennis Electrotennis was released by Epoch on September 12th, 1975 at a cost of either ¥19,000 yen or ¥19,500 yen.[1][2] The TV Tennis Electrotennis was the first Japanese video game console.[2][3]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]

Sales figures

[edit | edit source]Most sales figures for the TV Tennis Electrotennis are in the ballpark of around 10,000,[2] to 20,000 consoles sold.[4]

The German website Gamona even goes so far as to say the console could have sold over three million units, though this source notes that they were unsure of this claim.[5]

Influences

[edit | edit source]The ability for the TV Tennis Electrotennis to broadcast television signals inspired Famicom and NES designer Masayuki Uemura to consider adding a similar wireless broadcast function to the Famicom, though this was not pursued due to cost.[6]

TV Tennis Electrotennis (テレビテニス) is also known by its affectionate nickname "Pon Tennis" (ポンテニス).[7]

Technology

[edit | edit source]As the name suggests, the TV Tennis Electrotennis could only play tennis.[3] The system broadcast a television signal over a UHF antenna and ran on batteries so it did not need to be plugged into anything to work.[3][8]

External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Game Medium - TV Tennis Electrotennis page.

- Super Gaijin Ultra Gamer - TV Tennis Electrotennis page.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "ニッポンのゲーム37年史を学ぼう!". nippon.com (in Japanese). 3 October 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ↑ a b c "Japan’s 1st Video Game Console was released 40 Years ago!" (in en). Toarcade. 12 September 2015. https://toarcade.wordpress.com/2015/09/12/japans-1st-video-game-console-was-released-40-years-ago/. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c "1st Generation – Game Bros Central". Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ "TV Tennis Electrotennis". Wikipedia. 11 November 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ↑ "Retro-Gaming: Die allererste japanische Videospielkonsole feiert 40. Jubiläum". web.archive.org. 22 January 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190122044225/http://www.gamona.de/games/retro-gaming,die-allererste-japanische-videospielkonsole-feiert-40:news.html.

- ↑ "Feature: NES Creator Masayuki Uemura On Building The Console That Made Nintendo A Household Name". Nintendo Life. 3 March 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ "アタリ・ヴィデオ・コンピューター・システム – ザ・プロトタイプ20世紀が見た夢". WIRED.jp (in Japanese). Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ↑ Picard, Martin (December 2013). "The Foundation of Geemu: A Brief History of Early Japanese video games". Game Studies. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

![East German made televisions. Television played a major role in keeping East Germans informed on West German culture.[10]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f9/20180208_172139_Die_Welt_der_DDR.jpg/120px-20180208_172139_Die_Welt_der_DDR.jpg)

![The Coleco Telstar Arcade was a significantly different console in the series that used cartridges containing a processor and ROM.[12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c3/Coleco-Telstar-Arcade-Pongside-L.jpg/120px-Coleco-Telstar-Arcade-Pongside-L.jpg)