History of video games/Print version/Second Generation of Video Game Consoles

| This is the print version of History of video games You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

- Second generation of video game consoles

Trends

[edit | edit source]Flooded Market

[edit | edit source]A huge number of consoles and video games flooded the market. Many of these consoles and games were low quality, and made it difficult for consoles offering innovative features or quality games to compete. This was one factor which lead to the video game crash of 1983.[1]

Digital programmable computers

[edit | edit source]This generation, many game consoles contained basic 8-bit computers. Rarely 4-bit and 16-bit computers would be used, like in the Game & Watch platform (4-bit)[2] or the Intellivision (16-bit),[3] though this had minimal impact on console graphics which were primarily constrained by other factors. Cartridge based systems became normal during this generation, and the introduction of digital programmable computers allowed game consoles to run software, which permitted more varied games than what the console designers originally intended.

Representative Graphics

[edit | edit source]This generation saw increased graphical capabilities of home game consoles, leading to less reliance on simple squares and rectangles in conjunction with overlays, and evolving to simple pixel artwork and rarely vector art. The pivotal choice between industry support for raster or vector graphics technology would hugely affect the industry going forward, with many genres of games favoring one or the other. The ultimate success of the use of raster graphics this generation would lead to their dominant use until the fifth generation of consoles. While these graphics would quickly be considered quite outdated by the mid to late 1980's, this step was a huge leap in quality and allowed more arcade style games to be played on home consoles.

This generation saw the first handheld consoles with basic screens. The displays were typically not visible in the dark and were monochrome only, but they still offered an improvement over the previous approach of using a few basic single color lights as output.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "No. 3038: The Video Game Crash of 1983". www.uh.edu. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ↑ "Game & Watch: Super Mario Bros. Review — Only 80s Kids Remember". DualShockers. 17 November 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ "Intellivision". kevtris.org. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

-

The Acetronic MPU 1000, one of the many consoles based on the 1292 Advanced Programmable Video System

History

[edit | edit source]The 1292 Advanced Video Programmable Video System was released in either 1976 or 1978.[1][2]

Technology

[edit | edit source]The 1292 Advanced Programmable Video System is powered by an 8-bit Signetics 2650AI processor[1][2] clocked at about 887kHz.

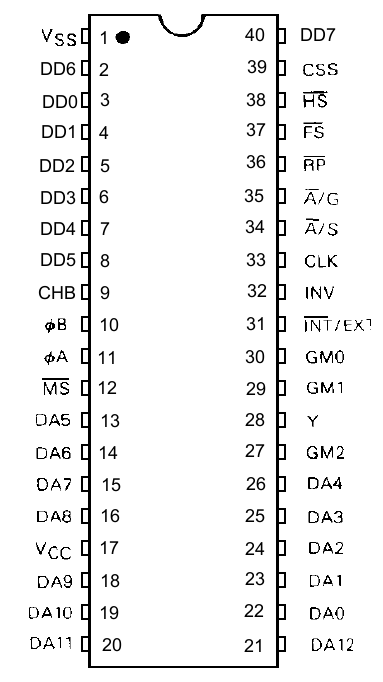

A Signetics 2636N Programmable Video Interface (PVI) chip clocked at 3.58 megahertz[3] is used for graphics, capable of rendering four sprites,[2][1] a background grid and four score digits. By programming in real-time during each scan of the TV picture, the sprites may be reprogrammed further down the screen. Similarly, score digits may be displayed at both the top and bottom of the screen. All video is generated from 113 registers in the PVI. As such, there is no video RAM in this system. The PVI also provides the programmer with 37 bytes of scratch memory that maybe used for variables.[4] A few games cartridges for these consoles such as chess included an extra 1kB of RAM.

Games

[edit | edit source]Two games were specific to the Voltmace Database.[5]

System Gallery

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- IGDB - 1292 Advanced Programmable Video System page with history and specs.

- Video Game Console Library - Page with history, specs, and photos of variants.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c "1292 Advanced Programmable Video System - Audiosonic PP-1292 Advanced Programmable Video System". www.igdb.com. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c "Video Game Console Library". Video Game Console Library. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ↑ "1292 Advanced Programmable Video System Console Information". Console Database. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ↑ "Signetics Programmable Video Interface (PVI) 2636" (PDF). Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ↑ "Videomaster / Voltmace Database Games-Computer (1980 - early 1980s)". Museum of Obsolete Media. 29 January 2015. https://obsoletemedia.org/voltmace-database-games-computer/.

-

An APF-MP1000 with controller removed from console.

History

[edit | edit source]Launch

[edit | edit source]The APF-MP1000 was released in 1978 to replace the older APF TV Fun line of consoles.[1][2] Uniquely for the time, the APF-MP1000 could be expanded into the Imagination Machine home computer via use of an add on module called the MPA-10.[3][4] The full Imagination Machine cost $599 and was released by 1979.[3][5] This price was considered low compared to competitors.[6] The Imagination Machine was developed by Ed Smith, one of the first African American engineers in the video game industry.[3]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]Between 20,000[7], and 50,000[3] APF-MP1000 consoles were sold.

APF saw its revenue drop 97% between 1981 and the video game crash of 1983.[3] Figures like this show the huge impact of the video game crash on company bottom lines. An Imagination Machine II was said to be planned but was never released.[5]

Technology

[edit | edit source]The APF-MP1000 uses an 8-bit Motorola 6800 CPU clocked at 3.579 megahertz.[5][1] This processor is not to be confused with the Motorola 68000, a more advanced processor commonly used on consoles several years following the launch of the MP1000.

The system has just 1 kilobyte of RAM.[1][8][9] The Imagination Machine computer upgrade gave the system 9 kilobytes of total RAM.[3]

Notable games

[edit | edit source]12 games were released for the APF-MP1000.[10]

The system has the game Rocket Patrol built-in to the system.[11]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Console

[edit | edit source]Detachable controllers

[edit | edit source]Internals

[edit | edit source]Technology

[edit | edit source]-

The APF-MP1000 Power Supply.

-

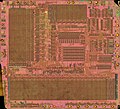

The die of a Motorola 6800 CPU, similar to the one used in the APF-MP1000.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ "ARCHIVE.ORG Console Library: APF-MP1000 : Free Software : Free Download, Borrow and Streaming : Internet Archive". archive.org. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e f "The Imagination Machine - Georgia State University News -". Georgia State News Hub. 15 March 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ "Home Page". Video Game Console Library. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c "DP FAQ". www.digitpress.com. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ Corporation, Bonnier. Popular Science. Bonnier Corporation. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ Ltd, Earl G. Graves (December 1982). "Black Enterprise" (in en). Earl G. Graves, Ltd.. https://books.google.com/books?id=N6pacvfrf0wC&pg=PA44&dq=APF-MP1000&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjEg5yw-LHtAhUKjVkKHdC0ApMQ6AEwCHoECAcQAg#v=onepage&q=APF-MP1000&f=false.

- ↑ "APF-MP1000 Pre-83". pre83.com. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ "Motorola 6800 microprocessor family". www.cpu-world.com. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ "History of Consoles: APF MP1000 (1978) Gamester 81". Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ "APF M1000 Video Game System Review". THE NORTHEAST OHIO VIDEO HUNTER. 1 August 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

-

The Emmerson Arcadia 2001.

History

[edit | edit source]

Phillips created an example platform for one of their chipsets, leading to a number of small mostly compatible consoles based on their specifications, one of the most popular being the Emerson Arcadia 2001.[1] Other notable compatible systems included the German Tele-Fever and the officially licensed Canadian console Leisure Vision.

Emerson Radio cooperation released the Emerson Arcadia 2001 in 1982.[2]

Thousands of game cartridges for the Arcadia 2001 were barred from sale due to legal issues.[2]

Technology

[edit | edit source]Compute

[edit | edit source]The console is powered by a Signetics 2650A CPU clocked at 3.58 MHz.[1]

The system has 1 kilobyte of RAM.[1] Some materials suggested the Emerson Arcadia 2001 had 28 or 24 kilobytes of RAM, which was not true.[3][4][5]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Console

[edit | edit source]Controller

[edit | edit source]Teardown

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ↑ a b "TOSEC: Emerson Arcadia 2001 (2012-04-23)". 23 April 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ↑ "Arcadia 2001 -- FAQ guide". www.digitpress.com. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "History of Consoles: Arcadia 2001 (1982) Gamester 81". Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "Home Page". Video Game Console Library. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

-

The Atari 2600 with joystick.

History

[edit | edit source]Development

[edit | edit source]Development of hardware which would become the Atari 2600 had begun by December 1975.[1] The prototype of the Atari 2600 was based on a Jolt card, which used a 6502 processor.[2] Software for the console was developed on a DEC PDP-11 minicomputer[2], which despite the classification name was a computer about the size of a refrigerator.[3] (And thus much smaller then room sized mainframes)

Launch

[edit | edit source]

The Atari 2600 was launched in 1977.[4] At launch the Atari 2600 cost $199.[5] Atari was able to leverage their strong arcade game brands to create home ports the same games - achieving massive market success.[6]

Early Atari 2600 units featured six switches and heavy RF shielding, which were later reduced to four switches and lighter shielding.[4]

In 1981 VCS cartridges cost as little as $20 and as much as $35.[6]

The launch of the Atari 5200 in 1982 may have harmed Atari 2600 sales, though a lack of coordination within Atari led to the Atari 2600 overshadowing it anyway.[7]

The 2700, a version of the 2600 with support for wireless controllers, was planned for a 1981 release but was scrapped with only a few prototype units being produced.[8]

The Video Game Crash

[edit | edit source]The combined success of Atari products in the home and in the arcade made the company a captain of industry, and the name Atari itself had become a cultural icon synonymous with video games and high technology. By 1982 Atari products had become so popular that it triggered an early panic among parents regarding possible negative effects of video games.[9][10] By 1983 some politicians involved in promoting new high tech industries in the United States were labeled as "Atari Democrats", a moniker which shows just how much pull Atari had on the public mindshare.[11] However this influence was not to last long, and Atari as well as the rest of the North American video game industry would soon find itself under an existential threat.

A major Christmas 1982 title, ET, was rushed into development and given only five and a half weeks of development time.[12] A contributing factor to the glut of systems and games on the market came from Atari requiring retailers to overstock their systems.[4] The game performed poorly on the market and caused massive financial harm to Atari.[12]

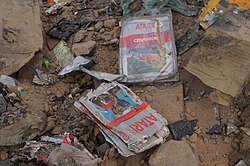

Landfill

[edit | edit source]

In September 1983 Atari disposed of surplus cartridges in a Alamogordo, New Mexico landfill.[12] This fact became an urban legend as time went on, until it was confirmed in a landfill dig.[12] Cartridges were found following 30 feet of digging.[13] The recovery project caused many to look at archeology in a new light, due to the recovery of something relatively recent.[13]

Later life and discontinuation

[edit | edit source]Following Nintendo's revival of the American video game market, Atari relaunched the system as the Atari 2600 Jr. in 1986.[4] The system was discontinued in 1992,[4][14] making the 2600 among the longest lasting consoles on the market.

Legacy

[edit | edit source]The Atari 2600 remained an iconic gaming system long after it was discontinued.

In 2021 various Atari 2600 games were used to demonstrate machine learning techniques at the organization Uber AI.[15][16]

In 2021 It was announced that Atari would begin producing new Atari 2600 cartridges as part of the Atari XP line.[17]

Myths

[edit | edit source]Due to its cultural prominence, a number of historically inaccurate myths have emerged regarding the system. One such false myth is that the blind musician Stevie Wonder was a spokesman for the system, though he was not.[18][19]

Technology

[edit | edit source]Compute

[edit | edit source]

The Atari 2600 used a MPU (CPU), the 8 bit MOS 6507 (Low cost version of the MOS 6502) clocked at 1.19MHz.[20] This processor was bottlenecked somewhat by poor IO performance.[14] A special chip is used to assist with graphics and sounds called the Television Interface Adapter (TIA)[14] which contains about 10,000 transistors and handles two (first version) or three (Later revision) sprites.[21] The Atari 2600 had 128 bytes of RAM, and up to a 4KB ROM.[22]

Some games, such as Pitfall II, used expansion chips to enhance the graphical and audio capabilities of the Atari 2600.[4]

Because of it's limitations, developers resorted to a number of tricks to make the most of the system performance.[23] As an example, some skilled commercial developers and skilled Demoscene creators would later be able to push to Atari 2600 to perform pseudo 3D Games or simple 3D via raycasting.[24][25]

Controller

[edit | edit source]A third party motion sensing controller that used mercury switches, the Le Stick, was released for the system.[26] This is a notable example of an early motion controller for a home console.

Notable games

[edit | edit source]Over 500 games were released for the Atari 2600.[27]

1977

[edit | edit source]

- Combat - Launch title and common pack-in cartridge, based on the arcade hit games Tank (1974) and Jet Fighter (1975).

- Video Olympics - Launch title

1978

[edit | edit source]- Super Breakout - port of the 1975 arcade game (see Pong and Breakout), using full-color graphics, instead of the black and white of the original version.

1979

[edit | edit source]1980

[edit | edit source]Adventure

[edit | edit source]Adventure was an early game in the Action adventure genre.[4] This game contained the first example of an Easter Egg in a game, the name of it's programmer Warren Robinett, as a way to protest Atari's decision not to credit programmers.[4]

1981

[edit | edit source]1982

[edit | edit source]- Pitfall!

- Yars' Revenge

- Donkey Kong - Port

- Pac-Man - Port

- Frogger

- Demon Attack

- Atlantis

- Megamania

- Cosmic Ark

- Centipede

- Raiders of the Lost Ark

- Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back

- E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial

River Raid

[edit | edit source]River Raid was an early console game to use procedural generation to save limited console resources.[28]

Notably, this game became the first to be banned in West Germany in 1984 as it portrayed paramilitary content.[28][29]

Read more about River Raid on Wikipedia.

1983

[edit | edit source]Pepsi Invaders

[edit | edit source]Pepsi Invaders is among the rarest games for the system with only 125 copies produced by Coca-Cola working with Atari.[30][31]

Read more about Pepsi Invaders on Wikipedia.

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Console variants

[edit | edit source]Wood veneer

[edit | edit source]Wood veneer light sixer

[edit | edit source]All Black

[edit | edit source]Sears Tele-Games Video Arcade

[edit | edit source]Controllers

[edit | edit source]Accessories

[edit | edit source]-

The Atari 2600 AC adapter takes AC electricity from mains and turns it 9 volt, 500 mAh DC current.

-

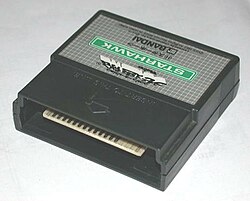

The Starpath Supercharger is an adapter allowing to run much bigger games from audio cassette.

-

The Spectravideo CompuMate (German Universum HEIMCOMPUTER variant pictured) was a membrane keyboard allowing to turn the Atari 2600 into a primitive computer running BASIC.

Development

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Atari Museum - Atari 2600 section.

- AtariAge - Atari 2600 section.

- Atari Mania - Atari 2600 section.

- Old Computers - Atari 2600 page

- The Strong National Museum of Play National Toy Hall of Fame - Atari 2600 page.

- Science Museum Group (UK) - Atari 2600 Page.

- Retro Games UK - Atari VCS page.

References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ "Gamasutra - The History of Atari: 1971-1977". www.gamasutra.com. https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/130414/the_history_of_atari_19711977.php?print=1.

- ↑ a b "Atari 2600 prototype - CHM Revolution". www.computerhistory.org. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ "An Entire PDP-11 On Your Bench". Hackaday. 24 August 2019. https://hackaday.com/2019/08/24/an-entire-pdp-11-on-your-bench/.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h "Gamasutra - A History of Gaming Platforms: Atari 2600 Video Computer System/VCS". www.gamasutra.com. https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/131956/a_history_of_gaming_platforms_.php?print=1. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ↑ "Atari 2600 Teardown". iFixit. 1 September 2010. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ a b Kunkel, Bill; Katz, Arnie (21 November 1981). "THE VIDEOGAMES: HOW THEY RATE (Published 1981)". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1981/11/21/style/the-videogames-how-they-rate.html.

- ↑ Trautman, Ted. "Excavating the Video-Game Industry’s Past" (in en-us). The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/business/currency/excavating-the-video-game-industrys-past.

- ↑ "Super Rare Atari 2700 Found At California Thrift Store" (in en-us). Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/super-rare-atari-2700-found-at-california-thrift-store-1797394693.

- ↑ "Children of the ‘80s Never Fear: Video Games Did Not Ruin Your Life" (in en). Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/children-80s-never-fear-video-games-did-not-ruin-your-life-180963452/.

- ↑ "Opinion VIDEO GAMES FOR THE 'BASEST INSTINCTS OF MAN' (Published 1982)". The New York Times. 28 January 1982. https://www.nytimes.com/1982/01/28/opinion/l-video-games-for-the-basest-instincts-of-man-151899.html.

- ↑ "InfoWorld" (in en). InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.. 28 November 1983. https://books.google.com/books?id=sy8EAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA151#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ↑ a b c d Robarge, Drew (15 December 2014). "From landfill to Smithsonian collections: "E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial" Atari 2600 game" (in en). National Museum of American History. https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/landfill-smithsonian-collections-et-extra-terrestrial-atari-2600-game. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ↑ a b "Archaeologists Dig for Video Games - Blog - The Henry Ford - Blog - The Henry Ford". www.thehenryford.org. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ↑ a b c "The Consumer Electronics Hall of Fame: Atari 2600". IEEE Spectrum: Technology, Engineering, and Science News. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ↑ Amer, Pakinam. "Machine Learning Pwns Old-School Atari Games" (in en). Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode/gamer-machine-learning-vanquishes-old-school-atari-games/.

- ↑ "Uber AI plays any Atari 2600 game with 'superhuman' skill". Engadget. https://www.engadget.com/uber-ai-masters-atari-games-012832222.html.

- ↑ Handley, Zoey (16 November 2021). "Atari XP will let you put some new cartridges in your old Atari 2600". Destructoid. https://www.destructoid.com/atari-xp-limited-edition-physical-cartridges-let-you-put-new-games-in-your-old-atari-2600/.

- ↑ "Did Stevie Wonder Endorse Atari Video Games?". Snopes.com. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ↑ "Sorry, That Crazy Stevie Wonder + Atari Poster Is Fake" (in en-AU). Kotaku Australia. 1 May 2014. https://www.kotaku.com.au/2014/05/sorry-that-crazy-stevie-wonder-atari-poster-is-fake/.

- ↑ "Atari Compendium". www.ataricompendium.com. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ↑ "Atari Compendium". www.ataricompendium.com. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ↑ "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ↑ "Inventing the Atari 2600" (in en). IEEE Spectrum. 15 December 2021. https://spectrum.ieee.org/atari-2600.

- ↑ Beyman, Alex (4 January 2019). "Pushing the Crusty Old Atari 2600 to its Absolute Limit" (in en). Medium. https://alexbeyman.medium.com/pushing-the-crusty-old-atari-2600-to-its-absolute-limit-e90e9aa053cb.

- ↑ "Raycasting on VCS". AtariAge Forums. https://atariage.com/forums/topic/284798-raycasting-on-vcs/.

- ↑ "Datasoft Le Stick Joystick - Peripheral - Computing History". www.computinghistory.org.uk. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "Atari game cartridges collage - CHM Revolution". www.computerhistory.org. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ a b "The Women Who Raided Rivers and Crushed Centipedes". High Score Esports. 8 March 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ↑ "River Raid causes "erratic thinking"". AtariAge Forums. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ↑ "Pepsi Invaders Retro Gamer". www.retrogamer.net. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ↑ "Atari 2600 VCS Pepsi Invaders : scans, dump, download, screenshots, ads, videos, catalog, instructions, roms". www.atarimania.com. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ↑ a b "Atari VCS (Darth Vader) - Game Console - Computing History". www.computinghistory.org.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

-

The Atari 5200 with controller attached.

History

[edit | edit source]

Launch

[edit | edit source]

The Atari 5200 was released in the United States of America in the summer of 1982 at a cost of $270.[1]

The console struggled in the market, as regular consumers did not like that the 5200 could not play their old 2600 games they owned.[2] While backwards compatibility as a concept was novel to game systems at the time, a lack of support for old games harmed sales. Complicating matters, poor coordination by Atari lead to 2600 games flooding the market after the Atari 5200 release,[3] which probably harmed the success of the system by not only reducing the incentive to upgrade, but also by releasing major games that would be incompatible with the 5200.

Legacy

[edit | edit source]Production of the Atari 5200 ceased by May 21st, 1984 as Atari announced the successor system - the Atari 7800.[4][5] Over one million Atari 5200 consoles were sold.[6]

Technology

[edit | edit source]The Atari 5200 was based on the Atari 400 computer[7] and used an 8-bit 6502C CPU clocked at 1.79 megahertz.[1] The Atari 5200 has 16 kilobytes of RAM.[1] The Atari 5200 had 2 kilobytes of storage for its BIOS.[4]

By being based off of Atari home computers, game ports from these computers to the 5200 were supposed to be easier.[8] The trade off was a radically different architecture from the prior Atari 2600, potentially resulting in less portability between the two.

Notable games

[edit | edit source]Wikipedia has a list of Atari 5200 games.

Special Editions

[edit | edit source]A special version of the 5200 was made for use in hotels.[8]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]4 Port Console

[edit | edit source]Controllers

[edit | edit source]Other items

[edit | edit source]Internals

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ Patterson, Patrick Scott (1 November 2017). "Back to the Future: A Look at the History of Backwards Compatibility". Scholarly Gamers. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ Trautman, Ted. "Excavating the Video-Game Industry’s Past" (in en-us). The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/business/currency/excavating-the-video-game-industrys-past.

- ↑ a b "History of Consoles: Atari 5200 (1982) Gamester 81". Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ Sanger, David E. (22 May 1984). "ATARI VIDEO GAME UNIT INTRODUCED (Published 1984)". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ↑ "Atari 5200 SuperSystem (1982 - 1984)". Museum of Obsolete Media. 7 March 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ "Atari 5200 console - CHM Revolution". www.computerhistory.org. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ a b "ATARI 5200 SUPERSYSTEM FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS". Retrieved 14 January 2021.

History

[edit | edit source]Development

[edit | edit source]

The Atari Cosmos was devised by Roger Hector, Allan Alcorn, and Harry Jenkins.[1] The Atari Cosmos casing was designed by Roy Nishi.[1]

The development of the Cosmos lead to internal hologram manufacturing breakthroughs at Atari, allowing them to go from individually making each hologram to mass-producing them at a cost of several cents per hologram.[2]

The Atari Cosmos was essentially a fully developed product with at least 3 working units and more dummy units produced, but was not released to the public.[3] A unit at the 1981 New York Toy Fair garnered significant interest and 8,000 preorders.[1] Marketing positioned the Cosmos as a high end product worthy of a high price tag, which coupled with low production costs would have made the Cosmos very profitable for Atari.[2] However wishy washy feelings from Management lead to the Atari Cosmos being scrapped.[2]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]Despite never seeing a release the Atari Cosmos had a huge impact on gaming, as it's failure to launch resulted in some of Atari's most talented staff, including Pong creator Allan Alcorn and key R&D staff such as Roger Hector leaving the company.[2] Roger Hector would later bring his talents to the Sega Technical Institute (STI),[4] and Namco.[5]

The Atari Cosmos had an impact on the broader world as well. The Cosmos would have also been one of the first commercial uses of holograms in a consumer product.[2] Some of the Atari staff working on mass-producing holography would leave Atari to apply their expertise security holograms instead, such as those used on credit cards.[2][6] Similar holograms would find use in applications fighting fraud and counterfeit items.[7]

Technology

[edit | edit source]The COPS411 CPU powers the Atari Cosmos.[1]

The Atari Cosmos used changeable two image holographic backgrounds,[3][8] an interesting choice which decisively differentiates the Atari Cosmos from its contemporary competition. The idea is similar in concept to the overlay strategy used by other consoles to give color to monochrome games, but used to create a simple holographic background instead of a colored foreground. Gameplay graphics are generated in the foreground by a comparatively mediocre matrix of 42 red LEDs (7 LED wide, 6 LED tall resolution) giving the console a low resolution,[3] even when compared to contemporary handhelds. Two incandescent lightbulbs are positioned to allow manipulation of the hologram.[1] From this the Cosmos can effectively control two backgrounds from the hologram, either the left side or the right side.[2]

The console has 9 built in game types which were selected by the cartridge pressing a button when inserted keeping cartridge costs low.[9][1] Thanks to the holographic background, "New" games could be cheaply and easily made by using a new hologram with an existing game type.[1] Thus while gameplay would be static, visuals would be updated. This also removed the need for game development to include programming after launch.

The Atari Cosmos takes 10.5 volts of AC Power at 750 milliamps.[1] The console is often described as a tabletop console, as it does not use a battery, and thus while easily portable, can't be used while away from a power outlet.[9][3]

The system has a model number of EG500.[3]

External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Video Game Kraken - Atari Cosmos page with history and photos

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c d e f g h "The Atari Cosmos Tabletop Game System". www.atarimuseum.com. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Stilphen, Scott (2013). "Roger Hector interview". www.ataricompendium.com. http://www.ataricompendium.com/archives/interviews/roger_hector/interview_roger_hector.html.

- ↑ a b c d e "Atari Cosmos". www.handheldmuseum.com. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ "Sega-16 – Interview: Roger Hector (Director of STI)". Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ↑ "Gamasutra - A Veteran With Character: Roger Hector Speaks". www.gamasutra.com. https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3672/a_veteran_with_character_roger_.php?print=1.

- ↑ "Spawn of Atari". https://www.wired.com/1996/10/atari-2/.

- ↑ Shah, Ruchir Y.; Prajapati, Prajesh N.; Agrawal, Y. K. (2010). "Anticounterfeit packaging technologies". Journal of Advanced Pharmaceutical Technology & Research. 1 (4): 368–373. doi:10.4103/0110-5558.76434. ISSN 2231-4040. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ↑ "Buy An Original Atari "Cosmos" Hologram" (in en-us). Wired. https://www.wired.com/2007/06/buy-an-original-2/.

- ↑ a b "Cosmos by Atari – The Video Game Kraken". Retrieved 24 January 2021.

-

The Bally Professional Arcade alongside a controller.

History

[edit | edit source]

The Bally Arcade was originally developed by Midway.[1][2] Midway had been producing machines for amusement arcades since 1958,[3][4] giving the console significant pedigree.

Announced in 1977, the Bally Astrocade was launched in April 1978 at a cost of $299.[5][6][7] Cartridges cost as little as $24.95 and as much as $39.95.[8] The launch of the console was somewhat botched by an initial attempt to sell the console through mail order and specialty computer shops rather then at traditional retail outlets.[5] The Bally Astrocade was known for its high end graphical capabilities while on the market as late as 1982.[2]

A Bally Astrocade was used in the development of the early digital art piece Digital TV Dinner by Jamie Faye Fenton, which was broadcast on television in 1978.[9] While not a game itself, this early piece of digital art utilized game glitches to create a meaningful artistic experience worthy of public distribution. This was also among the first notable exhibitions of glitch art.[9]

The Astrocade was later acquired by Astrovision, a company based in the city of Columbus in Ohio,[1][2] roughly around 1980.[8] The system was on the market until 1984 or 1985,[5][6][7] a fairly long time on the market for a console of this generation.

Technology

[edit | edit source]The Bally Astrocade has an 8-bit Z80 CPU clocked at 3.579 megahertz.[5][7] The Astrocade has 4 kilobytes of RAM.[7] The system has an 8 kilobyte ROM which is loaded with four software applications.[10]

Early models of the system were especially prone to overheating, though all units suffered from cooling issues.[11]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Console

[edit | edit source]Internals

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b Dunn, Jeff. "Chasing Phantoms - The history of failed consoles". gamesradar. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ a b c "Home Video Games: Video Games Update". www.atarimagazines.com. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ↑ "RIP Midway Games 1958-2009 (In Name Only)" (in en). n4g.com. https://n4g.com/news/358896/rip-midway-games-1958-2009-in-name-only.

- ↑ "4 Video Game Companies We Really Miss". CBR. 27 June 2020. https://www.cbr.com/video-game-companies-we-miss/.

- ↑ a b c d "The Torchinsky Files: I'm Betting Most Of You Have Never Seen A Bally Professional Arcade" (in en-us). Jalopnik. https://jalopnik.com/the-torchinsky-files-im-betting-most-of-you-have-never-1844218806. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ a b "Bally Astrocade (1977 - 1984)". Museum of Obsolete Media. 24 March 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c d "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ a b Kunkel, Bill; Katz, Arnie (21 November 1981). "THE VIDEOGAMES: HOW THEY RATE (Published 1981)". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1981/11/21/style/the-videogames-how-they-rate.html.

- ↑ a b "Stored in Memory: Recovering Queer and Transgender Life in Software History". Letters and Science. https://uwm.edu/letters-science/event/stored-in-memory-recovering-queer-and-transgender-life-in-software-history/.

- ↑ "Bally Professional Arcade". www.progettoemma.net. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ↑ "THE BALLY/ASTROCADE FAQ". Retrieved 14 January 2021.

-

The Bandai Supervision Console

History

[edit | edit source]Not to be confused with the later, but unrelated, Watara Supervision handheld game console.

The Bandai Super Vision 8000 was released in 1979 for 60,000 yen as the first cartridge based system released in the Japanese market.[1][2]

Bandai acquired rights to sell the Intellivision in the Japanese market and discontinued the Bandai Super Vision 8000 less than a year after launch to focus on the Intellivision.[1][3]

Technology

[edit | edit source]The Bandai Super Vision 8000 uses a NEC D780C (Z80 compatible) 8-bit CPU clocked at 3.58MHz.[3][4] The system uses a General Instrument AY-3-8910 coprocessor.[1]

Game library

[edit | edit source]- Beam Galaxian[5]

- Gun Professional[5]

- Missile Vader[5]

- Space Fire[5]

- PacPacBird[5]

- Submarine[5]

- Othello[5]

-

Packaging for the system.

-

An NEC D780C-1, a similar processor to the one used in the Bandai Super Vision.

References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ a b c "System Overview: System Overview - Bandai Super Vision 8000 - Beyond the Mind's Eye - Thoughts & Insights from Marriott_Guy". www.rfgeneration.com. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ Dunn, Jeff. "Chasing Phantoms - The history of failed consoles". gamesradar. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ a b "Video Game Console Library". Video Game Console Library. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ "5 Video Game Consoles That Never Came To The U.S." Playbuzz. 7 February 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e f g "Bandai Super Vision 8000". Wikipedia. 25 July 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

-

The original Epoch TV Game Cassette Vision.

-

The smaller Epoch TV Game Cassette Vision Jr.

History

[edit | edit source]The Cassette Vision saw a Japanese only launch on June 30th, 1981.[1][2] The Cassette Vision was sold for 13,500 yen, and games were sold for 4,000 yen.[3][2] The Cassette Vision sold over 400,000 consoles and was the most popular console in Japan for a time.[3][4] The system was held back in part by internal factors, as Epoch only had a single NEC TK-80 computer to be used for game development, limiting the Cassette Vision's library.[3][5]

The Cassette Vision was discontinued in 1984.[1] and would be followed by the improved Super Cassette Vision.

Technology

[edit | edit source]An NEC D777C CPU was included on Cassette Vision game cartridges.[6][7] This hardware was considered dated at the time.[3]

Cartridges for the system had a storage capacity of 2 kilobytes.[6]

Game library

[edit | edit source]Cassette Vision game cartridges cost around 4,000 yen each.[2]

- Astro Command[8]

- Galaxian - Despite the name this game is actually based on Moon Cresta, and not the more popular game also known as Galaxian.[8] This was a launch title.[3]

- Kikori no Yosaku[8]

- Baseball[8] - A launch title.[3]

- New Baseball[8]

- Battle Vader[8]

- Big Sports 12[8]

- PakPak Monster[8]

- Monster Mansion[8]

- Monster Block[8]

- Elevator Panic[8]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Video Game Console Library - Cassette Vision page with history, technical information, and photos.

- Old Computers Museum - NEC TK-80 page.

References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ a b "Epoch Cassette Vision (1981 - 1984)". Museum of Obsolete Media. 23 February 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e f "THE FORGOTTEN EPIC". The Game Scholar. 10 June 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "CLASSIC VIDEOGAME STATION ODYSSEY/EVENT/EARLY CREATERS". www.ne.jp. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "Cassette Vision by Epoch – The Video Game Kraken". Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ↑ a b "Video Game Console Library". Video Game Console Library. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ Riddle, Sean. "decaps". Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k "Cassette Vision". Wikipedia. 24 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

-

The Children's Discovery System. Note the unique keyboard, which features ABCD layout on one side, and function keys on the other.

History

[edit | edit source]Development

[edit | edit source]

Mattel brought on Professor Dr. Gordon Berry of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) as an educational consultant for the system.[1]

Launch

[edit | edit source]The Children's Discovery System was launched in 1981[2] at a cost of $125.[3]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]The Children's Discovery system was discontinued in 1984.[4]

Technology

[edit | edit source]The Display of the Children's Discovery System has a matrix LCD with a 16 by 48 pixel resolution.[5]

The system has an integrated membrane keyboard.[5]

Notable games

[edit | edit source]- Math I[6]

- Arcade Action I[6]

- Words I[6]

- Art[6]

- Music[6]

- Words II[6]

- Arcade Action II[6]

- Memory and Logic[6]

- Geography I[6]

- Foods[6]

- Fractions I[6]

- Fractions II[6]

- Science I[6]

- Presidents[6]

- Computer Programming[6]

- Spelling Fun[6]

External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Computer History Museum - Children's Discovery System page.

- Handheld Museum - Mattel 1981 Toy Fair Catalog clipping.

- RAM OK ROM OK - Children's Discovery System page.

References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ "Personal Computing 1982 02". 1 February 1982. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ "The Children's Discovery System computerized learning system 102630217 Computer History Museum". www.computerhistory.org. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ↑ Freedman, Alix M. (15 November 1981). "ELECTRONIC GAMES: DO THEY HELP? (Published 1981)". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ↑ "Children's Discovery System • Mattel • 1981 : RAM OK ROM OK". Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "Mattel Children's Discovery System". AtariAge Forums.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p w:Children's Discovery System

History of video games/Platforms/ColecoVision/ColecoVision

History

[edit | edit source]The Colorvision was launched in 1984 and sold under multiple brands.[1][2]

The Colorivsion was discontinued in 1985.[3]

Technology

[edit | edit source]

The Romtec Colorvision uses 2 C type batteries and game cartridges containing an LCD screen.[1][4] The game cartridges contain no software, but simply indicate which games built into the console should run.[1]

The integrated circuit on the motherboard is epoxied.[1]

Game library

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Handheld Museum - Colorvision page.

- Video Game Kraken - Colorvision by Romtec page.

- Game Medium - Colorvision page.

- Handheld Empire - Colorvision page.

- Electronic Plastic - Colorvision page.

References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ a b c d "Romtec Colorvision system". www.handheldmuseum.com. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ↑ "Colorvision by Bristol from Retrogames". www.retrogames.co.uk. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e f "Colorvision by Romtec – The Video Game Kraken". Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ↑ "Romtec: Colorvision Master Unit (vintage hand-held game)". HandheldEmpire. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

History

[edit | edit source]Background

[edit | edit source]The game of Mah-Jong has existed since at least the 1800's.[1] Mah-Jong became a popular game in Japan from the 1920's on, following its introduction from China.[2] Thus Nintendo would try to bring a portable electronic version of the popular board game to market.

Launch

[edit | edit source]Nintendo launched the Computer Mah-Jong Yakuman in 1983 for 16,800 yen.[3]

The Computer Mah-Jong Yakuman was succeeded by the Nintendo Game Boy, which would feature the return of the Computer Mah-Jong Yakuman brand as the 1989 GameBoy Yakuman cartridge. Unusually for a Nintendo console, the system has been poorly documented, and relatively little is known of its history.

Technology

[edit | edit source]The Computer Mah-Jong Yakuman uses a black and white dot matrix LCD.[3]

The Computer Mah-Jong Yakuman supported a link cable for multiplayer, becoming one of the first consoles to support a console to console communication standard by default.[3][4]

The Computer Mah-Jong Yakuman is powered by four AA batteries.[5] The system could also take 6V DC input.[6]

The console bore the model number MJ 8000.[5]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Handheld Museum - Computer Mah-Jong Yakuman page.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Walters, Ashley (15 July 2013). "From China to U.S., the game of mahjong shaped modern America, says Stanford scholar" (in en). Stanford University. https://news.stanford.edu/news/2013/july/humanities-mahjong-history-071513.html.

- ↑ Matsutani, Minoru (15 June 2010). "Mah-jongg ancient, progressive". The Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2010/06/15/reference/mah-jongg-ancient-progressive/.

- ↑ a b c Voskuil, Geplaatst door Erik. "Nintendo Computer Mah-jong Yakuman (コンピュータ マージャン 役満, 1983)". Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ↑ Jan. 26, Benj Edwards (26 January 2017). "The Lost World of Early Nintendo Consoles". PCMag Asia. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "Nintendo: Computer Mah-jong Yakuman - コンピュータ マージャン 役満 (vintage hand-held game)". HandheldEmpire. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ↑ "コンピューターマージャン役満" (in ja). takuya matsubara blog. https://nicotakuya.hatenablog.com/entry/20081016/1224166871.

History

[edit | edit source]The Digi Casse was released by Bandai in 1984.[1][2] The Digi Casse saw a European release sometime about 1986.[3] The console was sold with two game cartridges.[3]

Technology

[edit | edit source]

The Digi Casse is powered by two LR44 watch batteries.[1]

Notable games

[edit | edit source]Japan

[edit | edit source]Europe

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Handheld Museum Digi Casse A page.

- Handheld Museum Digi Casse B page.

- Game Medium Digi Casse page.

References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ a b "Video Game Console Library Handhelds". Video Game Console Library. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ "Bandai: Digi Casse B (vintage hand-held game)". HandheldEmpire. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "Re:Enthused Hardware: Bandai Digi Casse". Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h "Digi Casse". Wikipedia. 14 December 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

-

The Entex Select-A-Game console in a styrofoam case.

History

[edit | edit source]The Entex Select-A-Game was released in 1981 for $54.99.[1][2] Unlike most portable consoles of the time, it was designed to be used with two players, but could also be used by a single person.[3]

The use of games that were clear clones of other games on the console caused significant legal issues for Entex.[2]

Technology

[edit | edit source]Like many systems of the time, the CPU is located in game cartridges.[1]

The Entex Select-A-Game uses a Vacuum Florescent Display (VFD) with a resolution of 7 by 16 oval elements that could display red and white.[1]

The system used 4 C batteries.[1]

Notable games

[edit | edit source]

- Space Invader 2[1][2]

- Pacman 2[1][2]

- Baseball 4[1][2]

- Football 4[1][2]

- Basketball 3[1][2]

- Pinball[1][2]

External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Video Game Kraken - Entex Select-A-Game page.

- Handheld Museum - Entex Select-A-Game page.

References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

-

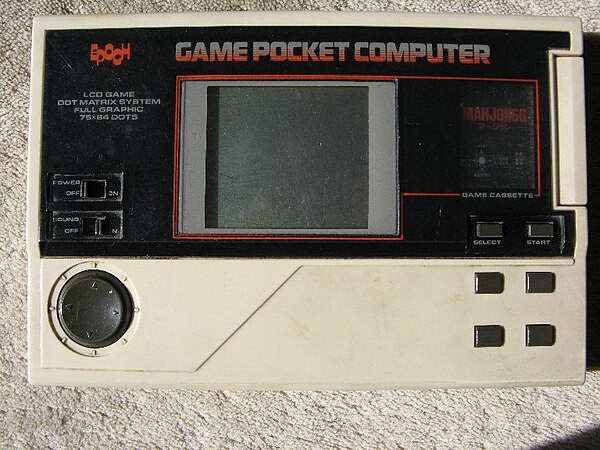

An Epoch Game Pocket Computer, experiencing case degradation from age.

History

[edit | edit source]1984 saw the Japanese release of the Epoch Game Pocket Computer, known as the Pokekon for short.[1][2][3] Having failed commercially in Japan, it did not see an international release.[4]

Technology

[edit | edit source]Compute

[edit | edit source]The Epoch Game Pocket Computer had an 8-bit NEC uPD78C06 CPU clocked at 6 megahertz.[2]

The system 2176 bytes (About two kilobytes) of RAM and four kilobytes of built in ROM, with cartridges having either 8 kilobytes or 16 kilobytes of ROM.[2]

General

[edit | edit source]The LCD has a resolution of 75 by 64 pixels and can show two shades.[2][3][5]

4 AA batteries give an impressive 70 hours battery life.[2][3] Not only was this impressive at the time, the power efficiency of the console remains one of the best in the history of portable game consoles.

Software

[edit | edit source]The Epoch Game Pocket Computer has built in system software, such as its paint program.[6]

Game library

[edit | edit source]Built in

[edit | edit source]- An 11 tile puzzle game

- A raster graphics editor

Cartridges

[edit | edit source]- Astro Bomber

- Block Maze

- Pocket Computer Mahjong

- Pocket Computer Reversi

- Sokoban

Gallery

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Video Game Kraken - Game Pocket Computer page.

- Chris Covell - Epoch Game Pocket Computer page.

- Handheld Museum - Epoch Game Pocket Computer page.

- Game Medium - Game Pocket Computer page.

References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ "Epoch Game Pocket Computer • Epoch • 1984 : RAM OK ROM OK". Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e "Chris Covell's Epoch Game Pocket Computer page". chrismcovell.com. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c "Epoch Game Pocket Computer". www.handheldmuseum.com. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ "ARCHIVE.ORG Console Library: Epoch Game Pocket Computer : Free Software : Free Download, Borrow and Streaming : Internet Archive". archive.org. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ "Epoch Game Pocket Computer [BINARIUM]". binarium.de. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ↑ "Epoch Game Pocket Computer - Ultimate Console Database". ultimateconsoledatabase.com. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

-

Fairchild Channel F

-

Fairchild Channel F II

History

[edit | edit source]

Jerry Lawson

[edit | edit source]Fairchild Semiconductor Engineer Jerry Lawson made an early arcade cabinet called Demolition Derby, which prompted Fairchild Semiconductor to quietly expand into the game industry.[1][2]

While working on the Fairchild Channel F, Lawson made the first real game cartridges, which contained software and could expand the RAM of the System.[3][2] Because of this Jerry Lawson is recognized as one of the most important figures in early gaming technology history for his invention of the cartridge, as well as one of the first African American engineers in the video game industry.[4][5]

Laswson's philosophy on games favored games that were skillful and grew the player.[6][7] He is remembered as an important early video game and computer industry figure in general, and became a symbol of African Americans in the gaming industry.[8][9]

Launch

[edit | edit source]

The Fairchild Channel F was released in November of 1976 at a cost of $169.95.[1][2]

The system was acquired by Zircon and relaunched around 1981 as a budget system.[10]

In 1981 Channel F cartridges cost as little as $18.95 and as much as $29.95.[10]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]

The Fairchild Channel F was discontinued in 1984,[11] coinciding with the video game market crash in the United States, but having been on the market for an exceptional amount of time. Around 250,000 Channel F consoles were sold.[6]

Following the Fairchild Channel F, Jerry Lawson would pursue other ventures, including an early attempt at console based network play.[12]

Technology

[edit | edit source]The Fairchild Channel F used Fairchild Semiconductor's own 8-bit F8 processor clocked at 1.7897725 megahertz.[13][2][14] It could process about 0.14 million instructions per second (MIPS).[15] Importantly, the F8 processor eliminated the need for many support chips required by competing processors,[16] and allowed for horizontal integration, making it a very economical choice for use in the Channel F.

The Fairchild Channel F had 64 bytes of RAM and 2 kilobytes of video RAM.[7]

The original Fairchild Channel F used an internal speaker, while the model II used television speakers.[17]

Games

[edit | edit source]A novelty at the time, some Fairchild Channel F games supported computer players, as well as pause functionality, which was known as "Hold" on games for the system.[18][17]

1978

[edit | edit source]Video Whizball

[edit | edit source]One of the first games to include an "Easter egg".[19][20]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Cartridge

[edit | edit source]-

Black Jack cartridge.

-

Cartridge contact pins.

-

Cartridge internals, showing the printed circuit board and two integrated circuits.

SABA Videoplay

[edit | edit source]-

SABA Videoplay, the German version of the Fairchild Channel F

-

Controller internals.

Technology

[edit | edit source]-

The Fairchild F3850 CPU, the heart of the F8 platform and similar to the chip used in the Channel F. This chip, an F3850PC 8621D△, was made in Malaysia.

-

PCB for the derivative Grandstand Video Entertainment Computer. Chips on this board come from Singapore, and a QA mark can be seen. Strangely, most metal on the circuit board has not been etched off, with only areas around the traces having been removed.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b Orland, Kyle. "Obituary: Fairchild Channel F Creator Jerry Lawson" (in en). www.gamasutra.com. https://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/124369/Obituary_Fairchild_Channel_F_Creator_Jerry_Lawson.php. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c d "Jerry Lawson And The Fairchild Channel F; Father Of The Video Game Cartridge". Hackaday. 14 July 2020. https://hackaday.com/2020/07/14/jerry-lawson-and-the-fairchild-channel-f-father-of-the-video-game-cartridge/. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ "Jerry Lawson, Inventor of Modern Game Console, Dies at 70" (in en-us). Wired. https://www.wired.com/2011/04/jerry-lawson-dies/. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ↑ Laurel, Capitol Technology University 11301 Springfield Road. "Gerald". www.captechu.edu. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ "Jerry Lawson: The Black Man Who Revolutionized Gaming As We Know It - IGN". Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ a b Snider, Mike. "Before Nintendo and Atari: How a black engineer changed the video game industry forever". USA TODAY. https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/2020/02/27/how-black-engineer-forever-changed-video-game-consoles/4752682002/. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ a b "VC&G » VC&G Interview: Jerry Lawson, Black Video Game Pioneer". https://www.vintagecomputing.com/index.php/archives/545/vcg-interview-jerry-lawson-black-video-game-pioneer. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ Chalk, Andy (2021-05-11). "Black videogame pioneer Jerry Lawson has a USC Games endowment named after him". PC Gamer. https://www.pcgamer.com/black-videogame-pioneer-jerry-lawson-has-a-usc-games-endowment-named-after-him/.

- ↑ Miller, Alex. "An Unsung Hero of Gaming History Deserves a Higher Profile". Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/jerry-lawson-unsung-hero-gaming-history-podcast/.

- ↑ a b Kunkel, Bill; Katz, Arnie (21 November 1981). "THE VIDEOGAMES: HOW THEY RATE (Published 1981)". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1981/11/21/style/the-videogames-how-they-rate.html.

- ↑ "Fairchild Channel F / Channel F System II (1976 – 1984)". Museum of Obsolete Media. 24 January 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ Ltd, Earl G. Graves. Black Enterprise. Earl G. Graves, Ltd. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ "Fairchild Channel F". Universal Videogame List. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ↑ "Fairchild Channel F Pre-83". pre83.com. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ↑ Murnane, Kevin. "From Pong To Playstation: The 40-Year Evolution Of Gaming Processing Power". Forbes. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ "Great Microprocessors of the Past and Present (V 13.4.0)". www.cpushack.com. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ↑ a b "Fairchild Channel F (1976-1982)" (in en). History of Console Gaming. 23 September 2016. https://hiscoga.wordpress.com/fairchild-channel-f/.

- ↑ "Early Home Video Game History: Making Television Play - The Strong National Museum of Play". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ "Easter Eggs in Video Games". Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ↑ Fries, Ed. "The Hunt For The First Arcade Game Easter Egg" (in en-us). Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/the-hunt-for-the-first-arcade-game-easter-egg-1793593889.

-

The Gakken Compact Vision TV Boy featured a truly unique design.

History

[edit | edit source]Gakken Founding

[edit | edit source]Gakken was founded in April of 1946 to provided educational services during the post World War II reconstruction of Japan.[1] Gakken began making educational electronic kits in the 1970's.[2]

Launch

[edit | edit source]The Gakken Compact Vision TV Boy was released in Japan in October[3] of 1983[4] for 8,800 yen.[5]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]The Gakken Compact Vision TV Boy is mostly remembered for its unique design. This strange control scheme is both credited as a factor in the failure of the console, while simultaneously hailed as a bold design that has its own fans.[6]

After the Compact Vision TV Boy, Gakken would not completely exit the gaming industry. It continued to manufacture 4-bit educational computers capable of extremely simple games in the 1980's.[7] A new model in this 4-bit computer line, The Gakken GMC-4, was released as recently as 2009, which included several simple games game,[7] and could be reprogrammed to play new games. Importers charged $39.95 for the GMC-4 system in 2009.[8]

Technology

[edit | edit source] The 8-bit Motorola MC6801 Microcontroller is kept on the game cartridges.[5][3] A Motorola MC 6847 video display generator and 2 kilobytes of RAM resides in the console.[3][5][9] This approach gave the Gakken Compact TV Boy some of the advantages of systems that kept the computer in the cartridge, as well as the cost saving advantages of reusing hardware between games.

The 8-bit Motorola MC6801 Microcontroller is kept on the game cartridges.[5][3] A Motorola MC 6847 video display generator and 2 kilobytes of RAM resides in the console.[3][5][9] This approach gave the Gakken Compact TV Boy some of the advantages of systems that kept the computer in the cartridge, as well as the cost saving advantages of reusing hardware between games.

Game library

[edit | edit source]Excite Invader

[edit | edit source]Excite Invader[10] was a 1983 game inspired by Space Invaders,[11] and considered to be among the best for the system.[12] The name of this game is sometimes listed as "Excite Invaders".[5]

External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Video Game Kraken - Gakken Compact Vision TV Boy page.

References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ a b c "Overview Gakken Holdings". ghd.gakken.co.jp. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ↑ Vis, Peter J. "Gakken EX-System". www.petervis.com. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ↑ a b c "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ "Site News: The True Holy Grails of Video Game Hardware - "The Minors" - Beyond the Mind's Eye - Thoughts & Insights from Marriott_Guy". www.rfgeneration.com. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i "Compact Vision TV Boy by Gakken – The Video Game Kraken". Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "The 10 Worst Video Game Systems of All Time". PCWorld. 14 July 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ↑ a b "New Gakken 4-bit Micro Computer Kit". Retro Thing. https://www.retrothing.com/2009/07/new-gakken-4bit-micro-computer-kit.html.

- ↑ "Gakken Gmc-4: 4-Bit Microcomputer Kit Won'T Play Crysis". Technabob. 22 October 2009. https://technabob.com/blog/2009/10/22/gakken-gmc-4-bit-microcomputer-kit/.

- ↑ "Motorola 6847". Wikipedia. 16 September 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e f "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ↑ Williams, Samuel (June 24, 2021). "The 10 Worst Video Game Consoles (& The Best Game For Each One)". https://www.cbr.com/best-games-for-worst-consoles/.

History

[edit | edit source]

Development

[edit | edit source]Gunpei Yokoi came up with the idea for the Game & Watch while watching a businessman fiddle with a calculator while traveling on the Shinkansen (Bullet Train).[1] A chance incident requiring Gunpei Yokoi to drive Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi to a meeting allowed him to pitch the idea, with approval being suddenly granted after a week of consideration.[2]

Sharp produced the electrical components used in the Game & Watch.[3] Engineers were split between hardware and software roles for development of the Game & Watch units.[3] Development pace for the Game & Watch series was frantic, and developers were usually focused on quickly developing new units.[4] While at least some of the developers of the Game & Watch were not informed of hard sales numbers, they were pressed into the sales at busy times to sell their own console in stores, which helped them better understand what their customers wanted.[4]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]

The D-Pad pioneered on the Game & Watch units was reused in subsequent Nintendo consoles, such as the Famicom/Nintendo Entertainment System.[3] The Game & Watch series sold 43.4 million units worldwide, with 30.53 million consoles sold outside of Japan, 12.87 million consoles sold inside Japan, and with 9 models of the console being attributable to selling over a million sales each.[4][5]

The Game & Watch line would see several continuations into the 2020's, either as in game homages, special edition themed consoles, software complications or even hardware releases such as the Nintendo Mini Classics series, and the Game & Watch: Super Mario Bros. console.

Technology

[edit | edit source]Game & Watch consoles reused calculator chips, and simply used displays with graphics rather than numbers to achieve the desired effect.[1]

The 4-bit Sharp SM5X series of microcontrollers served as the processor for Game & Watch units.[6]

The clock functionality was implemented with the use of a crystal oscillator.[1]

Due to their uncomplicated electronics and rugged design Game & Watch units tend to be reliable.[7]

Game library

[edit | edit source]Development

[edit | edit source]Clone consoles

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c "Iwata Asks". iwataasks.nintendo.com. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ "How Gunpei Yokoi Reinvented Nintendo". www.vice.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c O'Kane, Sean (18 October 2015). "7 things I learned from the designer of the NES". The Verge. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c "Iwata Asks". iwataasks.nintendo.com. https://iwataasks.nintendo.com/interviews/#/clubn/game-and-watch-ball-reward/0/3.

- ↑ "The Million Selling Nintendo Game & Watch (G&W) Games - Warped Factor - Words in the Key of Geek.". www.warpedfactor.com. http://www.warpedfactor.com/2020/11/the-million-selling-nintendo-game-watch.html.

- ↑ "mamedev/mame". GitHub. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ↑ Life, Nintendo (8 September 2020). "Feature: How Nintendo's Game & Watch Took "Withered Technology" And Turned It Into A Million-Seller". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

-

The Intellivision console with one controller extended.

History

[edit | edit source]Development

[edit | edit source]

The Intellivision is based on the General Instrument GIMINI 8900 platform.[1]

Test marketing for the Intellivision occurred in the area around Fresno, California in 1979.[2]

Launch

[edit | edit source]

The Intellivision was released in 1980.[3] In 1981 the system cost $299.95.[4] Cartridges for the system cost between $24.95 and 34.95 in 1981.[4]

An internal group of highly paid, hardworking, and secretive team of developers known as the Blue Sky Rangers worked on producing games for the Intellivision through at least 1982.[5] A 1982 Ford concept car featured a built in Intellivision.[6]

The Intellivision and the Atari 2600 competed fiercely in the market, leading to the first major console war.[7]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]The Intellivision lasted on the market until 1990.[3] The Intellivision sold over 3 million consoles.[8]

Mattel's next console was the HyperScan in 2006, though there is little relation beyond the parent company between these consoles.

Technology

[edit | edit source]Compute

[edit | edit source]The Intellivision had a 16 bit General Instrument CP1610 CPU with 10 bit instructions clocked at 894.886 kilohertz (About 0.89 megahertz) and 1352 bytes of total RAM.[3][9][10]

The Intellivision output at a resolution of 160 by 196 pixels with 16 colors.[3]

Software

[edit | edit source]PlayCable

[edit | edit source]The Intellivision had an online service called PlayCable that operated from 1980 to 1983 that allowed downloading games over a cable TV connection.[9]

Third Party Lockout

[edit | edit source]The Intellivision II was released in 1982, featuring a ROM that tried to keep third parties who were not licensed from making games for the system.[11][12] This was among the first lockout methods used on a major console, and would refuse to boot unless a Mattel copyright screen was shown, though because this was implemented while the console had already been on the market, it caused incompatibility with some prior official games.[12] The system was not effective in stopping unauthorized third parties from publishing Intellivision games.[11][12]

Notable Games

[edit | edit source]125 games were released on the Intellivision.[3]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Mattel Intellivision

[edit | edit source]Sears Tele Games Super Video Arcade

[edit | edit source]Redesigns

[edit | edit source]-

Intellivision II

-

INTV System III

Accessories

[edit | edit source]-

Intellivision controller

-

The Intellivoice module.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ "GIMINI Systems – The Video Game Kraken". Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ↑ "Blue Sky Rangers Intellivision History". history.blueskyrangers.com. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e "Gamasutra - A History of Gaming Platforms: Mattel Intellivision". www.gamasutra.com. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ a b Kunkel, Bill; Katz, Arnie (21 November 1981). "THE VIDEOGAMES: HOW THEY RATE (Published 1981)". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1981/11/21/style/the-videogames-how-they-rate.html.

- ↑ "Intellivision Classic Video Game System / TV Guide Profile". web.archive.org. 14 May 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ↑ Torchinsky, Jason (11 February 2021). "Ford's 1982 Concept Car Had Pre-GPS SatNav And The First Integrated Video Game Console" (in en-AU). Gizmodo Australia. https://www.gizmodo.com.au/2021/02/fords-1982-concept-car-had-pre-gps-satnav-and-the-first-integrated-video-game-console/.

- ↑ "PS4, XBox continue bit battles" (in en). The Blade. https://www.toledoblade.com/business/technology/2013/11/10/Fight-for-gaming-consoles-supremacy-started-with-Atari-vs-Intellivision/stories/20131110042. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ "Intellivision - Game Console - Computing History". www.computinghistory.org.uk. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ a b "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ "Intellivision". kevtris.org. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ a b "CVGA Disassembled Second Generation (1976-1984) · Online Exhibits". apps.lib.umich.edu. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c "A Short History of Device Lockout Methods in Consumer Electronics, Part 1 Fantranslation.org". fantranslation.org. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

-

The Interton Video Computer 4000 with controller.

History

[edit | edit source]

The Interton Video Computer 4000 was released in Germany in 1978 and was discontinued in 1983.[1] It is a prominent member of a family of consoles called the Advanced Programmable Video System.[2]

Technology

[edit | edit source]The Interton Video Computer 4000 uses a Signetics 2650A CPU with a Signetics 2636 Programmable Video Interface (PVI).[1][3][2]

Uniquely, the Interton Video Computer 4000 had 37 bytes of RAM included within the PVI.[2] Some games cartridges such as Chess include an external 1kB RAM chip. Up to 6 kilobytes of ROM was inluded on the cartridges.[4]

Notable games

[edit | edit source]Gallery

[edit | edit source]Console

[edit | edit source]Controller

[edit | edit source]Internals

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Old Computers Museum - Interton Video Computer Page featuring history and specs.

- pre83 - Advanced Programmable Video System page with history and specs.

References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ a b "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c "Advanced Programmable Video System Pre-83". pre83.com. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "Interton VC 4000". AtariAge Forums. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "Interton VC 4000 (1978 – 1983)". Museum of Obsolete Media. 26 February 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ↑ a b c "Interton Video Computer 4000". Wikipedia. 17 January 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

History

[edit | edit source]The Leisure Vision is a licensed Canadian version of the Arcadia 2001 that was launched in 1982 and discontinued in 1984.[1][2][3] While the system is considered a landmark release in Canadian consoles,[3] little more is known about it.

Technology

[edit | edit source]The Leisure Vision uses a Signetics 2650A clocked at 3.58 megahertz, with a Signetics 2637 co processor.[1]

The Leisure Vision has 1 kilobyte of RAM.[1]

Game library

[edit | edit source]The Leisure Vision is said to have a somewhat larger library than the standard Arcadia 2001 compatible systems.[3]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ↑ "Leisure Vision - Ultimate Console Database at ultimateconsoledatabase.com". ultimateconsoledatabase.com. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c "Leisure Vision – Montreal Video Game Museum". Retrieved 31 October 2020.

-

The Magnavox Odyssey² and with two controllers.

History

[edit | edit source]Launch

[edit | edit source]The Magnavox Odyssey² was preceded by the original Magnavox Odyssey game console and the Odyssey series of dedicated consoles. Unlike those consoles, the Magnavox Odyssey² featured a full computer, and could run games on cartridges.

The Magnavox Odyssey² was launched in 1978 at a cost of $100.[1] Early titles often had poor support for the keyboard and other system features, though support improved over time.[2] A voice module was also released, which was another feature which was panned for its poor integration with games.[3]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]Magnavox Odyssey² production ended in March of 1984,[4] correlating with the Video Game Crash. The system had been on the market for a fairly long time, indicating company investment in the system.

The system was followed by the Philips Videopac+ G7400 in European markets, though this successor system too was scrapped during the Video Game Crash.

Technology

[edit | edit source]

The CPU of the Magnavox Odyssey² was an 8-bit Intel 8048 clocked at 1.79 megahertz.[1][5] The system had 64 bytes of RAM and 128 bytes of video RAM.[1][5]

The Odyssey² has a built in membrane keyboard with 49 keys.[6]

Notable games

[edit | edit source]- Quest for the Rings - An early video game to use a companion board game.[2][7]

- Stone Sling[7]

- Turtles[7]

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Console

[edit | edit source]Internals

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ a b c "History of Consoles: Magnavox Odyssey 2 (1978) Gamester 81". Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ a b Kunkel, Bill; Katz, Arnie (21 November 1981). "THE VIDEOGAMES: HOW THEY RATE (Published 1981)". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1981/11/21/style/the-videogames-how-they-rate.html.

- ↑ "Home Video Games: Video Games Update". www.atarimagazines.com. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ↑ "The Odyssey2 Timeline! - The Odyssey² Homepage!". www.the-nextlevel.com. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ↑ a b "Home Page". Video Game Console Library. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ "When Video Game Consoles Wanted (and Failed) to Be Computers". www.vice.com. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

-

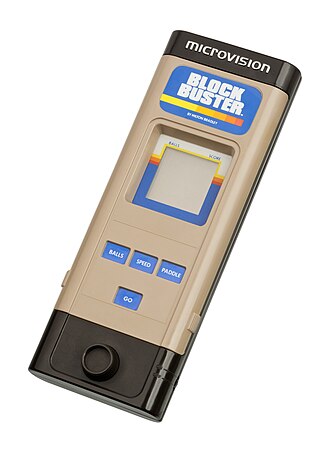

A Microvision handheld game console. The device is rather large compared to later handhelds.

History

[edit | edit source]Development

[edit | edit source]Milton Bradley was founded in 1860 to make board games[1], making it one of the oldest companies to have a major impact in the video game industry.

Jay Smith designed the Microvision and would later design the Vectrex.[2][3]

Launch

[edit | edit source]

The 1979 release of the Microvision was the first major portable console to use swappable cartridges, allowing a single system to play multiple games.[3]

The Microvision is seen in the 1981 movie Friday the 13th Part 2, a significant early appearance of a handheld game console in popular culture.[4][5]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]The Microvision was discontinued in 1981[4][6], though one game saw a Europe only release in 1982.[2] The failings of the Microvision design were lessons for Nintendo employees during the design of Game and Watch and Game Boy consoles.[7][8]

Technology

[edit | edit source]

Unlike most modern consoles but similar to many other consoles at the time, the Microvision contained processing elements on each game cartridge, not the console itself, though the clock speed used was always at 100 kilohertz (0.1 megahertz).[2] Cartridges either used an Intel 8021 CPU or a Texas Instruments TMS1100 CPU.[9]

The Microvision had a grey and black LCD with a resolution of 16 pixels by 16 pixels, and a size of 2 inches.[2][3] The screen ages poorly, and is prone to damage from screen rot.[10]

Cartridges were known to be quite fragile and especially vulnrable to electrostatic discharge.[11][12]

Early Microvision consoles required two 9 volt batteries, though later models only required a single 9 volt battery.[2]

Notable games

[edit | edit source]

1979

[edit | edit source]- Block Buster

- Bowling

- Baseball

- Connect Four

- Mindbuster

- Pinball

- Star Trek: Phaser Strike

- Vegas Slots

1980

[edit | edit source]- Baseball

- Sea Duel

1981

[edit | edit source]- Alien Raders

- Cosmic Hunter

1982

[edit | edit source]- Super Block Buster

Gallery

[edit | edit source]Microvision Console

[edit | edit source]Microvision Games

[edit | edit source]-

A Microvision game.

-

The back of a Microvision game.

Internals

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- Computer History Museum - Microvision page.

- Centre for Computing History - Microvision page.

- Video Game Kraken - Microvision page.

- Handheld Museum - Microvision page.

References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ Lepore, Jill. "The Meaning of Life". The New Yorker. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e "Microvision Console Review". videogamecritic.com. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ a b c "Microvision from Milton Bradley - IGN". Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ a b "History of Consoles-Microvision (1979) Gamester 81". Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ "Milton Bradley Microvision in Friday the 13th Part II". www.handheldmuseum.com. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ "Milton Bradley Microvison (1979 - 1981)". Museum of Obsolete Media. 27 September 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ Barder, Ollie. "New Interview With Satoru Okada Delves Into The Hidden History Behind Nintendo's Gaming Handhelds". Forbes. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ "Japanese Nintendo". Japanese Nintendo. 29 December 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ "MB Microvision - Intel 8021 inside?". AtariAge Forums. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ↑ Fletch, Toxic (10 December 2014). "Toxic Fletch: That Handheld Game in Friday the 13th Part 2". Toxic Fletch. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ↑ "The Marvelous MicroVision Handheld Videogame". Retro Thing. https://www.retrothing.com/2006/01/the_marvelous_m.html.

- ↑ "Milton Bradley Microvision (1979 - 1981)". Museum of Obsolete Media. 27 September 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

History

[edit | edit source]

The Palladium Tele-Cassetten Game was released by Neckermann in West Germany in either 1977[2][3] or 1978.[4][5][6] The system was sold as the MBO - Teleball Cassette and as the Hanimex - Optim 600.[2]

Little more is known about the history of this console.

Technology

[edit | edit source]General Instrument chips were used in game cartridges.[3]

The system could output color graphics, and used a built in speaker for audio.[7][3]

The system saw two different case designs used over the course of its production.[3]

Included controllers were analog.[8] Up to two controllers could be used, and an optional digital controller could be used for one tank game.[3] The system could have potentially accepted a light gun.[2]

Game library

[edit | edit source]External Resources

[edit | edit source]- The Liberator - Offers a history of the console, as well as console photos including of the console interior.

References

[edit | edit source]| Parts of this page are based on materials from: Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. |

- ↑ "Neckermann (company)". Wikipedia. 18 November 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ↑ a b c "pongmuseum.com - and the ball was square... MBO - Teleball Cassette I". pongmuseum.com. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". www.old-computers.com. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "Palladium Tele-Cassetten Game (825/530) [BINARIUM]". binarium.de. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "Tele-Cassetten-Game (Video Game 1978)". IMDb. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ↑ "Emerson Arcadia 2001" (in en). DeHipGahn Gaming. 14 August 2013. https://dehipgahngaming.wordpress.com/2nd-generation-video-game-systems/emerson-arcadia-2001/.

- ↑ "Palladium Tele-Cassetten-Game". bilgisayarlarim.com. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ↑ "Palladium Tele-Cassetten-Game Game Console". www.the-liberator.net. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e f g "Palladium Tele-Cassetten Game". Wikipedia. 9 February 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

-

The Palmtex Portable Videogame System.

History

[edit | edit source]Launch

[edit | edit source]

The Palmtex Portable was released in 1983.[1]

The Palmtex Portable was among the first clamshell console designs.[2]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]According to the Video Game Kraken only 5,000 Palmtex Portables were sold out of the 30,000 units total were produced.[3] Remaining units were possibly destroyed.[3][4]

Technology

[edit | edit source]The Palmtex Portable uses cartridges with the system LCD built into the cartridges.[5][1] Overlays gave color to otherwise monochrome graphics.[6]