Remembering the Templars

Introduction

[edit | edit source]The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, commonly known as the Knights Templar, the Order of the Temple or simply as Templars, were among the most famous of the Roman Catholic Church military orders. Today they still are one of the most fascinating, even mysterious chapters of medieval times. Founded during the High Middle Ages after the First Crusade to help protect Christian pilgrims, the organization lasted for nearly two centuries and had a great impact in the then know world for some of their innovations and the impact they had then on the fringes of the Christian world.

The order was created in France and officially endorsed by Roman Catholic Church around 1129. It rose to become a favored charity throughout Christendom, and grew rapidly in membership and power. A military order of warrior monks, the Templar Knights in their distinctive white mantles with a red cross, were among the most skilled fighting units of the Crusades. Non-combatant members of the Order managed a large economic infrastructure throughout Christendom, innovating financial techniques that were an early form of banking, and building fortifications across Europe and the Holy Land.

The Templars' existence was tied closely to the Crusades; when the Holy Land was lost, support for the Order faded. Rumors about the Templars' secret initiation ceremony created mistrust, and King Philip IV of France (Philippe le Bel), deeply in debt to the Order, took advantage of the situation. In 1307, many of the Order's members in France were charged with heresy, arrested, tortured into giving false confessions, and then burned at the stake. Under pressure from King Philip, Pope Clement V disbanded the Order in 1312. The abrupt disappearance of a major part of the European infrastructure, the forced heretic confessions and intentional rumors aimed to discredit the order gave rise to speculation and legends which have kept the Templar name alive to the modern day. Only recently did we learn that in 1314 the Order had secretly been pardoned by Pope Clement V.

The age

[edit | edit source]To understand the Templars one must understand the context that prompted the creation of the order. The age where the events took place is commonly referred as the High Middle Ages the period of European history in the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries (AD 1000–1300). The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which by convention ends around 1500.

The key historical trend of the High Middle Ages was the rapidly increasing population of Europe, which brought about great social and political change from the preceding era. By 1250, some scholars say, the continent became overpopulated, reaching levels it would not see again in some areas until the 19th century. This trend was checked in the Late Middle Ages by a series of calamities, notably the Black Death but also including numerous wars and economic stagnation.

From about the year 1000 onwards, Western Europe saw the last of the barbarian invasions and became more politically organized. The Vikings had settled in the British Isles, France and elsewhere, whilst Norse Christian kingdoms were developing in their Scandinavian homelands. The Magyars had ceased their expansion in the 10th century, and by the year 1000, a Christian Kingdom of Hungary was recognized in central Europe. With the brief exception of the Mongol incursions, major barbarian invasions ceased.

In the 11th century, populations in the Alps began to settle new lands, some of which had reverted to wilderness after the end of the Roman Empire. In what is known as the "great clearances," vast forests and marshes of Europe were cleared and cultivated. At the same time settlements moved beyond the traditional boundaries of the Frankish Empire to new frontiers in eastern Europe, beyond the Elbe River, tripling the size of Germany in the process. Crusaders founded European colonies in the Levant, Spain conquered from the Moors, and the Normans colonized southern Italy, all part of the major population increase and resettlement pattern.

The High Middle Ages produced many different forms of intellectual, spiritual and artistic works. This age saw the rise of modern nation-states in Western Europe and the ascent of the great Italian city-states. The still-powerful Roman Church called armies from across Europe to a series of Crusades against the Seljuk Turks, who occupied the Holy Land. The rediscovery of the works of Aristotle led Thomas Aquinas and other thinkers to develop the philosophy of Scholasticism. In architecture, many of the most notable Gothic cathedrals were built or completed during this era.

Social Structure

[edit | edit source]The social structure between the 9th and 15th centuries in Europe, was mostly based in a system for structuring society around the relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labor, defined as Feudalism.

The term "feudal" or "feodal" is derived from the medieval Latin word feodum. It seems that the strongest theory is that the social structure and term evolved from Roman practices, taking in consideration that Rome's power and culture had a major impact in the continent. The basic pillar of power and economic structure of the Roman society was the Roman villa. Roman writers refer with satisfaction to the self-sufficiency of their villas, where they drank their own wine and pressed their own oil, a commonly used literary topos. An ideal Roman citizen was the independent farmer tilling his own land, and the agricultural writers wanted to give their readers a chance to link themselves with their ancestors through this image of self-sufficient villas. The truth was not too far from it, either, while even the profit-oriented latifundia probably grew enough of all the basic foodstuffs to provide for their own consumption. One must also consider that ownership of land (and state taxation) had been one of the major motivators for Rome expansionism.

Another clue is given by the word domicile. The domain of the dominus (the Latin word for master and owner). It was a title of sovereignty the term under the Roman Republic had all the associations of the Greek Tyrannos; refused during the early principate, it finally became an official title of the Roman Emperors under Diocletian (this is where the term dominate, used to describe a political system of Roman Empire in 284-476, is derived from).

It is interesting to note the meaning and concept behind he word spread and evolved. For instance Dominus, in the French language is equivalent of being "sieur", was the Latin title of the feudal, superior and mesne, lords, and later also an ecclesiastical and academical title. It is also origin of the English "sir" prefix. The shortened form "dom" is still used as a prefix of honor for ecclesiastics of the Catholic Church. The English colloquial use of "don" for a fellow or tutor of a college at a university is derived either from an application of the Spanish title to one having authority or position, or from the academical use of dominus. The earliest use of the word in this sense appears, according to the New English Dictionary, in Souths Sermons (1660). An English corruption, "dan", was in early use as a title of respect, equivalent to master.

The Spanish form "Don" is also a title, formerly applicable only to the nobility, and now one of courtesy and respect applied to any member of the better classes. The feminine form "doña" is similarly applied to a lady. Much like in the Portuguese language the title "Dom" is also an honorific, and formerly used by members of the blood royal and others on whom it has been conferred by the sovereign. The Spanish "doña" is also present as "dona".

In Italian, the title Don or Donna is also reserved for diocesan catholic clergymen, former nobles and persons of distinction in Southern Italy. In Romanian, the word "domn" (feminine "doamna") is both a title of the medieval rulers, and a mark of honor.

It is then here we find the roots for the Feudalism system, based not only on Roman culture but dependent on Roman law, even in the evolution and refinement on the separate social casts as they had been first established by the Greeks. It is also interesting to note that seemingly insulated cultures have evolved similar social structures, from the Mayan, in the kingdoms of China and in Japan.

At the bottom the serf, this class has its origins in the 2nd century AD in the way the Roman latifundia had displaced the small farms as the agricultural foundation of the Roman Empire. This effect contributed to the destabilizing of Roman society as well. As the small farms of the Roman peasantry were bought up by the wealthy and their vast supply of slaves, the landless peasantry were forced to idle and squat around the city of Rome, relying greatly on handouts. This new landless class, incapable of self sustain itself as we discussed earlier was one of the motives for the Roman expansionism. Services to the state were often recompensed with land, especially to the military service man.

And so the social pyramid stats to form, above the serf we have the Nobility. Every Noble starts by belonging to a feudal lord (owner of land) family, often they may have royal blood, nobility is attributed by the state in continuation with the practice by the Romans, were service is rewarded by land an position. Since most borders have now been established, the possession and control of land and people to toil and defend it becomes the cornerstone of power. The abundance of serfs makes past practices of slavery rare, serfs allegiance becomes as important as the recognition and hereditary rights (again in line with previous Roman practices). Religion was used not only as social agglutinator but as a justification for to right of rule, and so the Church becomes important validating the rulers of all kingdoms in Christianhood.

The evolution of states in most of Europe after the fall of Rome, started after the fragmentation of the empire. The Church become the only link and keeper of knowledge and culture, the only light during The Dark Ages after the extinguishing of the "light of Rome".

The Church that had in itself a very stratified hierarchical system, that replicated (even if with more freedom) the economic strata of those who joined the service of the Church in the preservation of knowledge, culture and the rule of law. It comes to represent of the Christian God will on Earth, and the ultimate seat of power. And so at the top we have the Clergy, that are the ultimate guarantees of social order and serve as the power not only behind each monarch but each citizen.

The Rise of Chivalry

[edit | edit source]Household heavy cavalry (knights) became common in the 11th century across Europe, and tournaments were invented. Although the heavy capital investment in horse and armor was a barrier to entry, knighthood became known as a way for serfs to earn their freedom. In the 12th century, the Cluny monks promoted ethical warfare and inspired the formation of orders of chivalry, such as the Templar Knights. Inherited titles of nobility were established during this period. In 13th-century Germany, knighthood became another inheritable title, although one of the less prestigious, and the trend spread to other countries.

It was with the religious military orders, that the fusion of the religious and the military spirit was realized, that chivalry reached its apogee. It was at this apogee that the secular brotherhood was created.

Religion

[edit | edit source]The Church

[edit | edit source]The East-West Schism of 1054 formally separated the Christian church into two parts: Western Catholicism in Western Europe and Eastern Orthodoxy in the east. It occurred when Pope Leo IX and Patriarch Michael I excommunicated each other, mainly over disputes as to the existence of papal authority over the four Eastern patriarchs.

Mendicant orders

[edit | edit source]- Franciscans (Friars Minor, commonly known as the Grey Friars), founded 1209

- Carmelites, (Hermits of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Carmel, commonly known as the White Friars), founded 1206–1214

- Dominicans (Order of Preachers, commonly called the Black Friars), founded 1215

- Augustinians (Hermits of St. Augustine, commonly called the austin Friars), founded 1256

Military orders

[edit | edit source]The Roman Catholic Christian military orders, society of knights, are intrinsically connected with the Crusades (the protection and expansion of the Roman Catholic Christian faith). The main goal of their creation was to answer the military structure requirements of the time as well with the maintaining of a distinction in regards to ranking of those from noble families called into the service of the Church. They first appeared following the First Crusade in response to the Islamic conquest of the former Byzantine Christian Holy Land. They evolved to propagating or defending the faith and guarantee access to Holy Land. Military actions were mostly against Islamic forces or in the suppression of heretics. Many orders later became secularized.

The foundation of the Templars in 1118 provided the first in a series of tightly organized military forces which protected the Christian lands in Outremer. Fighting invading Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula (Reconquista).

Because of the necessity to have a standing army, the military orders were created, being adopted as the fourth monastic vow.

The principal feature of the military order is the combination of military and religious ways of life. Some of them, like the Knights of St John and the Knights of Saint Thomas, also cared for the sick and poor. However, they were not purely male institutions, as nuns could attach themselves as convents of the orders. One significant feature of the military orders is that clerical brothers could be, and indeed often were, subordinate to non-ordained brethren.

In 1818 Joseph von Hammer compared the Catholic military orders, in particular the Templars, with certain Islamic models such as the Shiite sect of Assassins. In 1820 José Antonio Conde has suggested they were modeled on the ribat, a fortified religious institution which brought together a religious way of life with fighting the enemies of Islam. However popular such views may have become, others have criticized this view suggesting there were no such ribats around the Outremer until after the military orders had been founded. Yet the innovation of the role and function of the military orders has sometimes been obscured by the concentration on their military exploits in Syria, the Holy Land, Prussia, and Livonia. In fact they had extensive holdings and staff throughout Western Europe. The majority were laymen. They provided a conduit for cultural and technical innovation, for example the introduction of fulling into England by the Knights of St John, or the banking facilities of the Templars.

List of military orders

[edit | edit source]This list is intended to be comprehensive. The orders are listed chronologically according to their dates of foundation (in parentheses), which are sometimes approximate, and may in significance vary from case to case, the foundation of an order, its ecclesiastical approval, and its militarization occurring at times on different dates.

- Knights Hospitaller (1080)

- Order of Saint James of Altopascio (ca. 1075)

- Sovereign Military Order of Malta (1099)

- Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem (1113)

- Knights Templar (ca. 1118)

- Order of Saint Lazarus (ca. 1123)

- Order of Aviz (1128)

- Order of Saint Michael of the Wing (1147)

- Order of Calatrava (1158)

- Order of Aubrac (1162)

- Order of Santiago (1170)

- Order of Alcántara (1177)

- Order of Mountjoy (c.1180)

- Teutonic Knights (1190)

- Hospitallers of Saint Thomas of Canterbury at Acre (1191)

- Order of Monfragüe (1196)

- Order of Sant Jordi d'Alfama (1201)

- Livonian Brothers of the Sword (1202)

- Order of Dobrzyń (1216)

- Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mercy (1218)

- Knights of the Cross with the Red Star (before 1219)

- Militia of the Faith of Jesus Christ (1221)

- Order of the Faith and Peace (1231)

- Militia of Jesus Christ (1233)

- Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary (1261)

- Order of Santa María de España (1275)

- Order of Montesa (1317)

- Order of the Knights of Our Lord Jesus Christ (1318)

- Order of the Dragon (1408)

- Order of Saint Maurice (1434)

- Order of Our Lady of Bethlehem (1459)

- Order of Saint George of Carinthia (1469)

- Order of Saint George of Parma (before 1522)

- Order of Saint Stephen (1561)

Golden age of monasticism

[edit | edit source]The late 11th century/early-mid 12th century was the height of the golden age of Christian monasticism (8th-12th centuries).

- Benedictine Order - black robed monks

- Cistercian Order - white robed monks

Heretical movements

[edit | edit source]Heresy existed in Europe before the 11th century but only in small numbers and of local character: a rogue priest, or a village returning to pagan traditions; but beginning in the 11th century mass-movement heresies appeared. The roots of this can be found with the rise of urban cities, free merchants and a new money-based economy. The rural values of monasticism held little appeal to urban people who began to form sects more in tune with urban culture. The first heretical movements originated in the newly urbanized areas such as southern France and northern Italy. They were mass movements on a scale the Church had never seen before, and the response was one of elimination for some, such as the Cathars, and the acceptance and integration of others, such as St. Francis, the son of an urban merchant who renounced money.

Cathars

[edit | edit source]

The Cathars formed the Catharism movement with Gnostic elements that originated around the middle of the 10th century, branded by the contemporary Roman Catholic Church as heretical. It existed throughout much of Western Europe, but its home was in Languedoc and surrounding areas in southern France.

The name Cathar most likely originated from Greek catharos, "the pure ones". One of the first recorded uses is Eckbert von Schönau who wrote on heretics from Cologne in 1181: "Hos nostra germania catharos appellat."

The Cathars are also called Albigensians. This name originates from the end of the 12th century, and was used by the chronicler Geoffroy du Breuil of Vigeois in 1181. The name refers to the southern town of Albi (the ancient Albiga). The designation is hardly exact, for the centre was at Toulouse and in the neighbouring districts.

The Albigensians were strong in southern France, northern Italy, and the southwestern Holy Roman Empire.

- Dualists believed that historical events were the result of struggle between a good force and an evil force and that evil ruled the world, but could be controlled or defeated through asceticism and good works.

- Albigensian Crusade, Simon de Montfort, Montségur, Quéribus

Waldensians

[edit | edit source]Peter Waldo of Lyon was a wealthy merchant who gave up his wealth around 1175 and became a preacher. He founded the Waldensians which became a Christian sect believing that all religious practices should have scriptural basis.

Literature and art

[edit | edit source]At this time Medieval literature included a variety of cultures that influenced the literature of the High Middle Ages, one of the strongest among them being Christianity. The connection to Christianity was greatest in Latin literature, which influenced the vernacular languages in the literary cycle of the Matter of Rome. Other literary cycles, or interrelated groups of stories, included the Matter of France (stories about Charlemagne and his court), the Acritic songs dealing with the chivalry of Byzantium's frontiersmen, and perhaps the best known cycle, the Matter of Britain, which featured tales about King Arthur, his court, and related stories from Brittany, Cornwall, Wales and Ireland. There was also a quantity of poetry and historical writings which were written during this period, such as Historia Regum Britanniae by Geoffrey of Monmouth.

Southern France gave birth to Provençal literature, which is best known for troubadors who sang of courtly love. It included elements from Latin literature and Arab-influenced Spain and North Africa. Later its influence spread to several cultures in Western Europe, Portugal, the Minnesänger in Germany, Sicily and Northern Italy, later giving birth to the Italian Dolce Stil Nuovo of Petrarca and Dante, who wrote the most important poem of the time, the Divine Comedy.

Medieval art at this age included these major periods or movements:

- Romanesque art - traditions from the Classical world (not to be confused with Romanesque architecture)

- Gothic art - Germanic traditions (not to be confused with Gothic architecture).

- Byzantine art - Byzantine traditions.

- Christian art

- Anglo-Saxon art

- Jewish art - for example in the areas of specialty such as Illuminated manuscripts.

Technology

[edit | edit source]

During the 12th and 13th century in Europe there was a radical change in the rate of new inventions, innovations in the ways of managing traditional means of production, and economic growth. In less than a century there were more inventions developed and applied usefully than in the previous thousand years of human history all over the globe. The period saw major technological advances, including the adoption or invention of printing, gunpowder, the astrolabe, spectacles, a better clock, and greatly improved ships. The latter two advances made possible the dawn of the Age of Exploration.

Alfred Crosby described some of this technological revolution in The Measure of Reality : Quantification in Western Europe, 1250-1600 and other major historians of technology have also noted it.

- The earliest written record of a windmill is from Yorkshire, England, dated 1185.

- Paper manufacture began in Italy around 1270.

- The spinning wheel was brought to Europe (probably from India) in the 13th century.

- The magnetic compass aided navigation, first reaching Europe some time in the late 12th century.

- Eyeglasses were invented in Italy in the late 1280s.

- The astrolabe returned to Europe via Islamic Spain.

- Leonardo of Pisa introduces Arabic numerals to Europe with his book Liber Abaci in 1202.

- The West's oldest known depiction of a stern-mounted rudder can be found on church carvings dating to around 1180.

The Known World

[edit | edit source]

Climate and agriculture

[edit | edit source]The Medieval Warm Period, the period from 10th century to about the 14th century in Europe, was a relatively warm and gentle interval ended by the generally colder Little Ice Age. Farmers grew wheat well north into Scandinavia, and wine grapes in northern England, although the maximum expansion of vineyards appears to occur within the Little Ice Age period. This protection from famine allowed Europe's population to increase, despite the famine in 1315 that killed 1.5 million people. This increased population contributed to the founding of new towns and an increase in industrial and economic activity during the period. Food production also increased during this time as new ways of farming were introduced, including the use of a heavier plow, horses instead of oxen, and a three-field system that allowed the cultivation of a greater variety of crops than the earlier two-field system - notably legumes, the growth of which prevented the depletion of important nitrogen from the soil.

Trade and commerce

[edit | edit source]In Northern Europe, the Hanseatic League was founded in the 12th century, with the foundation of the city of Lübeck in 1158–1159. Many northern cities of the Holy Roman Empire became hanseatic cities, including Amsterdam, Cologne, Bremen, Hannover and Berlin. Hanseatic cities outside the Holy Roman Empire were, for instance, Bruges and the Polish city of Gdańsk (Danzig). In Bergen, Norway and Novgorod, Russia the league had factories and middlemen. In this period the Germans started colonizing Eastern Europe beyond the Empire, into Prussia and Silesia.

Westerners became more aware of the Far East, works like the presumably documented voyage of Marco Polo in Il Milione is an example. Followed by numerous Christian missionaries to the East, such as William of Rubruck, Giovanni da Pian del Carpini, Andrew of Longjumeau, Odoric of Pordenone, Giovanni de Marignolli, Giovanni di Monte Corvino, and other travellers such as Niccolo Da Conti.

Southern Europe

[edit | edit source]

Much of the Iberian peninsula, had been occupied by the Moors after 711, although the northernmost portion was divided between several Christian states. In the 11th century, and again in the thirteenth, a coalition of Christian kings under the leadership of Castile drove the Muslims from central and most of southern Spain. The County of Portugal ceased to be a vassal of the Kingdom of Asturias in 868. Spain started to be defined by the marriage in 1469 of future Queen Isabella and future King Ferdinand, joined together the royal houses of the Kingdom of Castile and the Kingdom of Aragon, but was only recognized in 1479 upon they ascendancy to their thrones.

In Italy in the Middle Ages, independent city states grew affluent on the eastern trade. These were in particular the thalassocracies of Pisa, Amalfi, Genoa and Venice.

- The Debate on the Trial of the Templars, 1307-1314

- D. Dinis e a supressão da Ordem do Templo (1312): o processo de formação da identidade nacional em Portugal

Eastern Europe

[edit | edit source]The High Middle Ages saw the height and decline of the Slavic state of Kievan Rus' and the emergence of Poland. Later, the Mongol invasion in the 13th century had great impact on Eastern Europe, as many countries of that region were invaded, pillaged, conquered and vassalized.

During the first half of this period (c.1025-1185) the Byzantine Empire dominated the Balkans south of the Danube, and under the Comnenian emperors there was a revival of prosperity and urbanization; however, the unity of the region came to an end with a successful Bulgarian rebellion in 1185, and henceforth the region was divided between the Byzantines in Greece, Macedonia and Thrace, and the Serbians and Bulgarians to the north. The Eastern and Western churches had formally split in the 11th century, and despite occasional periods of co-operation during the twelfth century, in 1204 the Fourth Crusade used treachery to capture Constantinople. This severely damaged the Byzantines, and their power was ultimately usurped by the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century.

Scandinavia

[edit | edit source]From the mid-tenth to the mid-eleventh centuries, the Scandinavian kingdoms were unified and Christianized, resulting in an end to Viking raids, and greater involvement in European politics. King Cnut of Denmark ruled over both England and Norway. After Cnut’s death in 1035, England and Norway were lost, and with the defeat of Valdemar II in 1227, Danish predominance in the region came to an end. Meanwhile, Norway extended its Atlantic possessions, ranging from Greenland to the Isle of Man, while Sweden, under Birger jarl, built up a power base in the Baltic Sea.

France and Germany

[edit | edit source]By the time of the High Middle Ages, the Carolingian Empire had been divided and replaced by separate successor kingdoms called France and Germany, although not with their modern boundaries. Germany was under the banner of the Holy Roman Empire, which reached its high-water mark of unity and political power.

Britain

[edit | edit source]

In Britain and Scotland, the Norman Conquest of 1066 resulted in a kingdom ruled by a French-speaking nobility. The Normans invaded Ireland in force in 1169 and soon established themselves throughout most of the country, though their stronghold was the southeast. Likewise, Scotland and Wales were subdued to vassalage at about the same time, though Scotland later regained her independence. The Exchequer was founded in the 12th century under King Henry I, and the first parliaments were convened. In 1215, after the loss of Normandy, King John signed the Magna Carta into law, which limited the power of English monarchs.

The Crusades and the Reconquista

[edit | edit source]The Crusades was one of the most important events of the period, consisting in a series of religious Crusades, in which Christians fought to retake Palestine from the Seljuk Turks. The Crusades impacted all levels of society in the High Middle Ages, from the kings and emperors who themselves led the Crusades, to the lowest peasants whose lords were often absent in the east. The height of the Crusades was the 12th century, following the First Crusade and the foundation of the Crusader states; in the 13th century and beyond, Crusades were also directed against fellow Christians, and in eastern and northern Europe, non-Muslim pagans. Expanded contact with the east, especially among the city-states of Italy, would eventually help spark the Italian Renaissance, that then spread throughout the whole of western Christendom. The late German 18th century theater play "Nathan the Wise" that unfolds in the 12th century Jerusalem can be interesting to better contextualize the epoch.

Third crusade

[edit | edit source]

Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon

[edit | edit source]

After the First Crusade captured Jerusalem in 1099, many Christian pilgrims traveled to visit what they referred to as the Holy Places. However, though the city of Jerusalem was under relatively secure control, the rest of Outremer was not. Bandits abounded, and pilgrims were routinely slaughtered, sometimes by the hundreds, as they attempted to make the journey from the coastline at Jaffa into the Holy Land.

Around 1119, the French knight Hugues de Payens approached King Baldwin II of Jerusalem with the proposal of creating a monastic order for the protection of these pilgrims. King Baldwin agreed to the request, and granted space for a headquarters in a wing of the royal palace on the Temple Mount, in the captured Al-Aqsa Mosque. The Temple Mount had a mystique because it was above what was believed to be the ruins of the Temple of Solomon. The Crusaders therefore referred to the Al Aqsa Mosque as Solomon's Temple, and it was from this location that the new Order took the name of Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon, or "Templar" knights. The Order, with about nine knights including Godfrey de Saint-Omer and André de Montbard, had few financial resources and relied on donations to survive. Their emblem was of two knights riding on a single horse, emphasizing the Order's poverty.

A Templar Knight is truly a fearless knight, and secure on every side, for his soul is protected by the armour of faith, just as his body is protected by the armour of steel. He is thus doubly armed, and need fear neither demons nor men."

De Laude Novae Militae—In Praise of the New Knighthood[1]

The Templars' impoverished status did not last long. They had a powerful advocate in Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, a leading Church figure and a nephew of André de Montbard, one of the founding knights. Bernard spoke and wrote persuasively on their behalf, and in 1129 at the Council of Troyes the Order was officially endorsed by the Church. With this formal blessing, the Templars became a favored charity throughout Christendom, receiving money, land, businesses, and noble-born sons from families who were eager to help with the fight in the Holy Land.

Another major benefit came in 1139, when Pope Innocent II's papal bull Omne Datum Optimum exempted the Order from obedience to local laws. This ruling meant that the Templars could pass freely through all borders, were not required to pay any taxes, and were exempt from all authority except that of the pope.

With its clear mission and ample resources, the Order grew rapidly.

Organization

[edit | edit source]Although the primary mission of the Order was military, relatively few members were combatants. The others acted in support positions to assist the knights and to manage the financial infrastructure. The Templar Order, though its members were sworn to individual poverty, was given control of wealth beyond direct donations. A nobleman who was interested in participating in the Crusades might place all his assets under Templar management while he was away. Accumulating wealth in this manner throughout Christendom and the Outremer, the Order in 1150 began generating letters of credit for pilgrims journeying to the Holy Land: pilgrims deposited their valuables with a local Templar preceptory before embarking, received a document indicating the value of their deposit, then used that document upon arrival in the Holy Land to retrieve their funds. This innovative arrangement was an early form of banking, and may have been the first formal system to support the use of cheques; it improved the safety of pilgrims by making them less attractive targets for thieves, and also contributed to the Templar coffers.

Based on this mix of donations and business dealing, the Templars established financial networks across the whole of Christendom. They acquired large tracts of land, both in Europe and the Middle East; they bought and managed farms and vineyards; they built churches and castles; they were involved in manufacturing, import and export; they had their own fleet of ships; and at one point they even owned the entire island of Cyprus. The Order of the Knights Templar arguably qualifies as the world's first multinational corporation.

The Templars were organized as a monastic order similar to Bernard's Cistercian Order, which was considered the first effective international organization in Europe. The organizational structure had a strong chain of authority. Each country with a major Templar presence (France, England, Aragon, Portugal, Poitou, Apulia, Jerusalem, Tripoli, Antioch, Anjou, Hungary, and Croatia) had a Master of the Order for the Templars in that region. All of them were subject to the Grand Master, appointed for life, who oversaw both the Order's military efforts in the East and their financial holdings in the West.

No precise numbers exist, but it is estimated that at the Order's peak there were between 15,000 and 20,000 Templars, of whom about a tenth were actual knights.

Ranks within the order

[edit | edit source]Three main ranks

[edit | edit source]There was a threefold division of the ranks of the Templars: the aristocratic knights, the lower-born sergeants, and the clergy. Knights were required to be of knightly descent and to wear white mantles. They were equipped as heavy cavalry, with three or four horses and one or two squires. Squires were generally not members of the Order but were instead outsiders who were hired for a set period of time. Beneath the knights in the Order and drawn from lower social strata were the sergeants. They were either equipped as light cavalry with a single horse or served in other ways such as administering the property of the Order or performing menial tasks and trades. Chaplains, constituting a third Templar class, were ordained priests who saw to the Templars' spiritual needs.

Grand Masters

[edit | edit source]

Starting with founder Hugues de Payens in 1118–1119, the Order's highest office was that of Grand Master, a position which was held for life, though considering the martial nature of the Order, this could mean a very short tenure. All but two of the Grand Masters died in office, and several died during military campaigns. For example, during the Siege of Ascalon in 1153, Grand Master Bernard de Tremelay led a group of 40 Templars through a breach in the city walls. When the rest of the Crusader army did not follow, the Templars, including their Grand Master, were surrounded and beheaded. Grand Master Gérard de Ridefort was beheaded by Saladin in 1189 at the Siege of Acre.

The Grand Master oversaw all of the operations of the Order, including both the military operations in the Holy Land and Eastern Europe and the Templars' financial and business dealings in Western Europe. Some Grand Masters also served as battlefield commanders, though this was not always wise: several blunders in de Ridefort's combat leadership contributed to the devastating defeat at the Battle of Hattin. The last Grand Master was Jacques de Molay, burned at the stake in Paris in 1314 by order of King Philip IV.

Behaviour and dress

[edit | edit source]It was Bernard de Clairvaux and founder Hugues de Payens who devised the specific code of behavior for the Templar Order, known to modern historians as the Latin Rule. Its 72 clauses defined the ideal behavior for the Knights, such as the types of garments they were to wear and how many horses they could have. Knights were to take their meals in silence, eat meat no more than three times per week, and not have physical contact of any kind with women, even members of their own family. A Master of the Order was assigned "4 horses, and one chaplain-brother and one clerk with three horses, and one sergeant brother with two horses, and one gentleman valet to carry his shield and lance, with one horse." As the Order grew, more guidelines were added, and the original list of 72 clauses was expanded to several hundred in its final form.

The knights wore a white surcoat with a red cross and a white mantle; the sergeants wore a black tunic with a red cross on front and back and a black or brown mantle. The white mantle was assigned to the Templars at the Council of Troyes in 1129, and the cross was most probably added to their robes at the launch of the Second Crusade in 1147, when Pope Eugenius III, King Louis VII of France, and many other notables attended a meeting of the French Templars at their headquarters near Paris.

According to their Rule, the knights were to wear the white mantle at all times, even being forbidden to eat or drink unless they were wearing it.

The red cross that the Templars wore on their robes was a symbol of martyrdom, and to die in combat was considered a great honor that assured a place in heaven. There was a cardinal rule that the warriors of the Order should never surrender unless the Templar flag had fallen, and even then they were first to try to regroup with another of the Christian orders, such as that of the Hospitallers. Only after all flags had fallen were they allowed to leave the battlefield. This uncompromising principle, along with their reputation for courage, excellent training, and heavy armament, made the Templars one of the most feared combat forces in medieval times.

Initiation, known as Reception (receptio) into the Order, was a profound commitment and involved a solemn ceremony. Outsiders were discouraged from attending the ceremony, which aroused the suspicions of medieval inquisitors during the later trials.

New members had to willingly sign over all of their wealth and goods to the Order and take vows of poverty, chastity, piety, and obedience. Most brothers joined for life, although some were allowed to join for a set period. Sometimes a married man was allowed to join if he had his wife's permission, but he was not allowed to wear the white mantle.

Battles involving Templars

[edit | edit source]Templars were often the advance force in key battles of the Crusades, as the heavily armored knights on their warhorses would set out to charge at the enemy, in an attempt to break opposition lines.

The Crusades: Siege of Ascalon (1153)

[edit | edit source]

The Crusades: Battle of Montgisard (1177)

[edit | edit source]The Battle of Montgisard occurred in November 25, 1177, at Montgisard, near Ramlah (now Ramla and part of Israel). Where some 500 Templar knights helped several thousand infantry to defeat Saladin's army of more than 26,000 soldiers.

The Crusades: Battle of Jacob's Ford (1179)

[edit | edit source]Jacob's Ford was the location of a strategic river crossing at the center of the Holly land. The river crossing was part of the regional route along the ancient Via Maris, dating from the early Bronze Age. This access to the territory that is toady Syria was always important for economic and military reasons but more so for the Crusaders / Catholic Church.

During the Crusades of the 12th century sections of the Mediterranean coastline of the territory that is now Syria were briefly held by Frankish overlords, forming the Crusader state of the Principality of Antioch. The area was also threatened by Shi'a extremists known as Assassins (Hassassin). In 1260, the Mongols arrived, led by Hulagu Khan with an army 100,000 strong, destroying cities and irrigation works. Aleppo fell in January 1260, and Damascus in March of the same year, but then the attack breaks off as Hulagu Khan needed to return to China to deal with a succession dispute.

Even today, now in the form of a bridge, it maintains a high military strategic importance, straddling the border between Israel and the Israeli-occupied portion of the Golan Heights (Syria) and is one of the few fixed crossing points over the northern Jordan River which enable access from the Golan Heights to the Upper Galilee.

The Battle of Jacob's Ford occurred in August 23, 1179, at Jacob's Ford, in what is now Syria.

The Crusades: Battle of Hattin (1187)

[edit | edit source]

The Battle of Hattin Battle of the Horns of Hattin in 1187, can be defined as the turning point in the Crusades.

The Crusades: Siege of Acre (1190–1191)

[edit | edit source]The Crusades: Battle of Arsuf (1191)

[edit | edit source]

The Crusades: Siege of Acre (1291)

[edit | edit source]

Templar symbolism

[edit | edit source]Gothic architecture

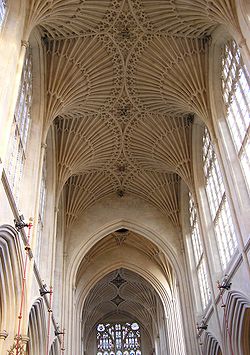

Gothic architecture superseded the Romanesque style by combining flying buttresses, gothic (or pointed) arches and ribbed vaults. It was influenced by the spiritual background of the time, being religious in essence: thin horizontal lines and grates made the building strive towards the sky. Architecture was made to appear light and weightless, as opposed to the dark and bulky forms of the previous Romanesque style. Saint Augustine of Hippo taught that light was an expression of God. Architectural techniques were adapted and developed to build churches that reflected this teaching. Colorful glass windows enhanced the spirit of lightness. As color was much rarer at medieval times than today, it can be assumed that these virtuoso works of art had an awe-inspiring impact on the common man from the street. High-rising intricate ribbed, and later fan vaultings demonstrated movement toward heaven. Veneration of God was also expressed by the relatively large size of these buildings. A gothic cathedral therefore not only invited the visitors to elevate themselves spiritually, it was also meant to demonstrate the greatness of God. The floor plan of a gothic cathedral corresponded to the rules of scholasticism: the plan was divided into sections and uniform subsections. These characteristics are exhibited by the most famous sacral building of the time: Notre Dame de Paris.

as reproduced in T. A. Archer, The Crusades: The Story of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (1894), p. 176. The design with the two knights on a horse and the inscription SIGILLVM MILITVM XRISTI is attested in 1191, see Jochen Burgtorf, The central convent of Hospitallers and Templars: history, organization, and personnel (1099/1120-1310), Volume 50 of History of warfare (2008), ISBN 9789004166608, pp. 545-546.</ref> |dates= c. 1119–1314 |allegiance=The Pope |type= Western Christian military order |role= Protection of Pilgrims |size= 15,000–20,000 members at peak, 10% of whom were knights[2][3]

|garrison=Temple Mount, Jerusalem |garrison_label=Headquarters |nickname=Order of the Temple |patron=St. Bernard of Clairvaux |motto= Non nobis Domine, non nobis, sed nomini tuo da gloriam (Not to us Lord, not to us, but to Your Name give the glory) |colors=White mantle with a red cross |colors_label=Attire |mascot= 2 Knights riding one horse

|commander1=Hugues de Payens |commander1_label=First Grand Master |commander2=Jacques de Molay |commander2_label=Last Grand Master

Buildings

[edit | edit source]

Decline

[edit | edit source]In the mid-12th century, the tide began to turn in the Crusades. The Muslim world had become more united under effective leaders such as Saladin, and dissension arose among Christian factions in and concerning the Holy Land. The Knights Templar were occasionally at odds with the two other Christian military orders, the Knights Hospitaller and the Teutonic Knights, and decades of internecine feuds weakened Christian positions, politically and militarily. After the Templars were involved in several unsuccessful campaigns, including the pivotal Battle of the Horns of Hattin, Jerusalem was captured by Saladin's forces in 1187. The Crusaders retook the city in 1229, without Templar aid, but held it only briefly. In 1244, the Khwarezmi Turks recaptured Jerusalem, and the city did not return to Western control until 1917 when the British captured it from the Ottoman Turks.[4]

The Templars were forced to relocate their headquarters to other cities in the north, such as the seaport of Acre, which they held for the next century. But they lost that, too, in 1291, followed by their last mainland strongholds, Tortosa (in what is now Syria), and Atlit. Their headquarters then moved to Limassol on the island of Cyprus,[5] and they also attempted to maintain a garrison on tiny Arwad Island, just off the coast from Tortosa. In 1300, there was some attempt to engage in coordinated military efforts with the Mongols[6] via a new invasion force at Arwad. In 1302 or 1303, however, the Templars lost the island to the Egyptian Mamluks in the Siege of Arwad. With the island gone, the Crusaders lost their last foothold in the Holy Land.[7][8]

With the Order's military mission now less important, support for the organization began to dwindle. The situation was complex though, as over the two hundred years of their existence, the Templars had become a part of daily life throughout Christendom.[9] The organization's Templar Houses, hundreds of which were dotted throughout Europe and the Near East, gave them a widespread presence at the local level.[3] The Templars still managed many businesses, and many Europeans had daily contact with the Templar network, such as by working at a Templar farm or vineyard, or using the Order as a bank in which to store personal valuables. The Order was still not subject to local government, making it everywhere a "state within a state"—its standing army, though it no longer had a well-defined mission, could pass freely through all borders. This situation heightened tensions with some European nobility, especially as the Templars were indicating an interest in founding their own monastic state, just as the Teutonic Knights had done in Prussia[10] and the Knights Hospitaller were doing with Rhodes.[11]

Arrests, charges, and dissolution

[edit | edit source]In 1305, the new Pope Clement V, based in France, sent letters to both the Templar Grand Master Jacques de Molay and the Hospitaller Grand Master Fulk de Villaret to discuss the possibility of merging the two Orders. Neither was amenable to the idea, but Pope Clement persisted, and in 1306 he invited both Grand Masters to France to discuss the matter. De Molay arrived first in early 1307, but de Villaret was delayed for several months. While waiting, De Molay and Clement discussed charges that had been made two years prior by an ousted Templar. It was generally agreed that the charges were false, but Clement sent King Philip IV of France a written request for assistance in the investigation. King Philip was already deeply in debt to the Templars from his war with the English and decided to seize upon the rumors for his own purposes. He began pressuring the Church to take action against the Order, as a way of freeing himself from his debts.[12]

On Friday, October 13, 1307 (a date sometimes spuriously linked with the origin of the Friday the 13th superstition)[13][14] Philip ordered de Molay and scores of other French Templars to be simultaneously arrested. The arrest warrant started with the phrase : "Dieu n'est pas content, nous avons des ennemis de la foi dans le Royaume" ["God is not pleased. We have enemies of the faith in the kingdom"].[15] The Templars were charged with numerous offences (including apostasy, idolatry, heresy, obscene rituals and homosexuality, financial corruption and fraud, and secrecy).[16] Many of the accused confessed to these charges under torture, and these confessions, even though obtained under duress, caused a scandal in Paris. All interrogations were recorded on a thirty metre long parchment, kept at the "Archives nationales" in Paris. The prisoners were coerced to confess that they had spat on the Cross : "Moi Raymond de La Fère, 21 ans, reconnais que (J'ai) craché trois fois sur la Croix, mais de bouche et pas de coeur" (free translation : "I, Raymond de La Fère, 21 years old, admit that I have spat three times on the Cross, but only from my mouth and not from my heart"). The Templars were accused of idolatry.[17]

After more bullying from Philip, Pope Clement then issued the papal bull Pastoralis Praeeminentiae on November 22, 1307, which instructed all Christian monarchs in Europe to arrest all Templars and seize their assets.[18]

Pope Clement called for papal hearings to determine the Templars' guilt or innocence, and once freed of the Inquisitors' torture, many Templars recanted their confessions. Some had sufficient legal experience to defend themselves in the trials, but in 1310 Philip blocked this attempt, using the previously forced confessions to have dozens of Templars burned at the stake in Paris.[19][20]

With Philip threatening military action unless the pope complied with his wishes, Pope Clement finally agreed to disband the Order, citing the public scandal that had been generated by the confessions. At the Council of Vienne in 1312, he issued a series of papal bulls, including Vox in excelso, which officially dissolved the Order, and Ad providam, which turned over most Templar assets to the Hospitallers.[22]

As for the leaders of the Order, the elderly Grand Master Jacques de Molay, who had confessed under torture, retracted his statement. His associate Geoffroi de Charney, Preceptor of Normandy, followed de Molay's example and insisted on his innocence. Both men were declared guilty of being relapsed heretics, and they were sentenced to burn alive at the stake in Paris on March 18, 1314. De Molay reportedly remained defiant to the end, asking to be tied in such a way that he could face the Notre Dame Cathedral and hold his hands together in prayer.[23] According to legend, he called out from the flames that both Pope Clement and King Philip would soon meet him before God. His actual words were recorded on the parchment as follows : "Dieu sait qui a tort et a pëché. Il va bientot arriver malheur à ceux qui nous ont condamnés à mort" (free translation : "God knows who is wrong and has sinned. Soon a calamity will occur to those who have condemned us to death").[15] Pope Clement died only a month later, and King Philip died in a hunting accident before the end of the year.[24][25][26]

With the last of the Order's leaders gone, the remaining Templars around Europe were either arrested and tried under the Papal investigation (with virtually none convicted), absorbed into other military orders such as the Knights Hospitaller, or pensioned and allowed to live out their days peacefully. By papal decree, the property of the Templars was transferred to the Order of Hospitallers, which also absorbed many of the Templars' members. In effect, the dissolution of the Templars could be seen as the merger of the two rival orders.[27] Some may have fled to other territories outside Papal control, such as excommunicated Scotland or to Switzerland. Templar organizations in Portugal simply changed their name, from Knights Templar to Knights of Christ – see Order of Christ (Portugal).[28]

Chinon Parchment

[edit | edit source]

In September 2001, a document known as the "Chinon Parchment" dated 17–20 August 1308 was discovered in the Vatican Secret Archives by Barbara Frale, apparently after having been filed in the wrong place in 1628. It is a record of the trial of the Templars and shows that Clement absolved the Templars of all heresies in 1308 before formally disbanding the Order in 1312,[29] as did another Chinon Parchment dated 20 August 1308 addressed to Philip IV of France, also mentioning that all Templars that had confessed to heresy were "restored to the Sacraments and to the unity of the Church". This other Chinon Parchment has been well known to historians [30][31][32] having been published by Étienne Baluze in 1693,[33] and by Pierre Dupuy in 1751.[34]

The current position of the Roman Catholic Church is that the medieval persecution of the Knights Templar was unjust, that nothing was inherently wrong with the Order or its Rule, and that Pope Clement was pressed into his actions by the magnitude of the public scandal and by the dominating influence of King Philip IV.[35][36]

Legacy

[edit | edit source]

With their military mission and extensive financial resources, the Knights Templar funded a large number of building projects around Europe and the Holy Land. Many of these structures are still standing. Many sites also maintain the name "Temple" because of centuries-old association with the Templars.[37] For example, some of the Templars' lands in London were later rented to lawyers, which led to the names of the Temple Bar gateway and the Temple tube station. Two of the four Inns of Court which may call members to act as barristers are the Inner Temple and Middle Temple.

Distinctive architectural elements of Templar buildings include the use of the image of "two knights on a single horse", representing the Knights' poverty, and round buildings designed to resemble the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.[38]

Modern organizations

[edit | edit source]

The story of the secretive yet powerful medieval Templars, especially their persecution and sudden dissolution, has been a tempting source for many other groups which have used alleged connections with the Templars as a way of enhancing their own image and mystery.[39] There is no clear historical connection between the Knights Templar, which were dismantled in the 14th century, and any of the modern organizations, of which the earliest emerged publicly in the 18th century, and are referred to as Neo-Templars by some authors.[40][41][42][43][44] However, there is often public confusion and many overlook the 400-year gap.

Legends and relics

[edit | edit source]

The Knights Templar have become associated with legends concerning secrets and mysteries handed down to the select from ancient times. Rumors circulated even during the time of the Templars themselves. Freemasonic writers added their own speculations in the 19th century, and further fictional embellishments have been added in popular novels such as The Lost symbol Ivanhoe, Foucault's Pendulum, and The Da Vinci Code;[45] modern movies such as National Treasure and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade; and video games such as Assassin's Creed and Broken Sword.[46]

Many of the Templar legends are connected with the Order's early occupation of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem and speculation about what relics the Templars may have found there, such as the Holy Grail or the Ark of the Covenant.[45][10][47][48] That the Templars were in possession of some relics is certain. Many churches still display holy relics such as the bones of a saint, a scrap of cloth once worn by a holy man, or the skull of a martyr; the Templars did the same. They were documented as having a piece of the True Cross, which the Bishop of Acre carried into battle at the disastrous Horns of Hattin.[49] When the battle was lost, Saladin captured the relic, which was then ransomed back to the Crusaders when the Muslims surrendered the city of Acre in 1191.[50] The Templars were also known to possess the head of Saint Euphemia of Chalcedon,[51] and the subject of relics came up during the Inquisition of the Templars, as several trial documents refer to the worship of an idol of some type, referred to in some cases as a cat, a bearded head, or in some cases as Baphomet. This accusation of idol worship levied against the Templars has also led to the modern belief by some that the Templars practiced witchcraft.[52] However, modern scholars generally explain the name Baphomet from the trial documents as simply a French misspelling of the name Mahomet (Muhammad).[45][53]

The Holy Grail quickly became associated with the Templars, even in the 12th century. The first Grail romance, Le Conte du Graal, was written around 1180 by Chrétien de Troyes, who came from the same area where the Council of Troyes had officially sanctioned the Templars' Order. Perhaps twenty years later Parzival, Wolfram von Eschenbach's version of the tale, refers to knights called "Templeisen" guarding the Grail Kingdom.[54] Another hero of the Grail quest, Sir Galahad (a 13th-century literary invention of monks from St. Bernard's Cistercian Order) was depicted bearing a shield with the cross of Saint George, similar to the Templars' insignia: this version presented the "Holy" Grail as a Christian relic. A legend developed that since the Templars had their headquarters at the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, they must have excavated in search of relics, found the Grail, and then proceeded to keep it in secret and guard it with their lives. However, in the extensive documents of the Templar inquisition there was never a single mention of anything like a Grail relic,[7] let alone its possession by the Templars, nor is there any evidence that a Templar wrote a Grail Romance.[55] In reality, most mainstream scholars agree that the story of the Grail was just that, a literary fiction that began circulating in medieval times.[45][10]

Another legendary object that is claimed to have some connection with the Templars is the Shroud of Turin. In 1357, the shroud was first publicly displayed by a nobleman known as Geoffrey of Charney,[56] described by some sources as being a member of the family of the grandson of Geoffroi de Charney, who was burned at the stake with De Molay.[57] The shroud's origins are still a matter of controversy, but in 1988, a carbon dating analysis concluded that the shroud was made between 1260 and 1390, a span that includes the last half-century of the Templars' existence.[58] The validity of the dating methodology has subsequently been called into question, and the age of the shroud is still the subject of much debate[59] despite the existence of a 1389 Memorandum by Bishop Pierre D'Arcis to the Avignon Antipope Clement VII mentioning that the image had previously been denounced by his predecessor Henri de Poitiers (Bishop of Troyes 1353-1370), stating "Eventually, after diligent inquiry and examination, he discovered how the said cloth had been cunningly painted, the truth being attested by the artist who had painted it, to wit, that it was a work of human skill and not miraculously wrought or bestowed."[60]

Notes

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Stephen A. Dafoe. "In Praise of the New Knighthood". TemplarHistory.com. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- ↑ Burman, p. 45.

- ↑ a b Barber, in "Supplying the Crusader States" says, "By Molay's time the Grand Master was presiding over at least 970 houses, including commanderies and castles in the east and west, serviced by a membership which is unlikely to have been less than 7,000, excluding employees and dependents, who must have been seven or eight times that number."

- ↑ Martin, p. 99.

- ↑ Martin, p. 113.

- ↑ Demurger, p.139 "During four years, Jacques de Molay and his order were totally committed, with other Christian forces of Cyprus and Armenia, to an enterprise of reconquest of the Holy Land, in liaison with the offensives of Ghazan, the Mongol Khan of Persia.

- ↑ a b Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedWorlds - ↑ Nicholson, p. 201. "The Templars retained a base on Arwad island (also known as Ruad island, formerly Arados) off Tortosa (Tartus) until October 1302 or 1303, when the island was recaptured by the Mamluks."

- ↑ Nicholson, p. 5.

- ↑ a b c Sean Martin, The Knights Templar: The History & Myths of the Legendary Military Order, 2005. ISBN 1-56025-645-1.

- ↑ Nicholson, p. 237.

- ↑ Barber, Trial of the Templars, 2nd ed. "Recent Historiography on the Dissolution of the Temple." In the second edition of his book, Barber summarizes the views of many different historians, with an overview of the modern debate on Philip's precise motives.

- ↑ "Friday the 13th". snopes.com. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ↑ David Emery. "Why Friday the 13th is unlucky". urbanlegends.about.com. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ↑ a b "Les derniers jours des Templiers". Science et Avenir: 52–61. 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Barber, Trial of the Templars, p. 178.

- ↑ Edgeller, Johnathan (2010). Taking the Templar Habit: Rule, Initiation Ritual, and the Accusations against the Order (PDF). Texas Tech University. pp. 62–66.

- ↑ Martin, p. 118.

- ↑ Martin, p. 122.

- ↑ Barber, Trial, 1978, p. 3.

- ↑ "Convent of Christ in Tomar". World Heritage Site. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Martin, p. 125.

- ↑ Martin, p. 140.

- ↑ Malcolm Barber has researched this legend and concluded that it originates from La Chronique métrique attribuée à Geffroi de Paris, ed. A. Divèrres, Strasbourg, 1956, pages 5711-5742. Geoffrey of Paris was "apparently an eye-witness, who describes Molay as showing no sign of fear and, significantly, as telling those present that God would avenge their deaths". Barber, The Trial of The Templars, page 357, footnote 110, Second edition (Cambridge University Press, 2006). ISBN 0521672368

- ↑ In The New Knighthood Barber referred to a variant of this legend, about how an unspecified Templar had appeared before and denounced Clement V and, when he was about to be executed sometime later, warned that both Pope and King would "within a year and a day be obliged to explain their crimes in the presence of God", found in the work by Ferretto of Vicenza, Historia rerum in Italia gestarum ab anno 1250 ad annum usque 1318 (Malcolm Barber, The New Knighthood, pages 314-315, Cambridge University Press, 1994). ISBN 0-521-55872-7

- ↑ "The Knights Templars". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

- ↑ Martin, pp. 140–142.

- ↑ "Long-lost text lifts cloud from Knights Templar". msn.com. October 12, 2007. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/21267691/?GT1=10450. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- ↑ Charles d' Aigrefeuille, Histoire de la ville de Montpellier, Volume 2, page 193 (Montpellier: J. Martel, 1737-1739).

- ↑ Sophia Menache, Clement V, page 218, 2002 paperback edition ISBN 0-521-592194 (Cambridge University Press, originally published in 1998).

- ↑ Germain-François Poullain de Saint-Foix, Oeuvres complettes de M. de Saint-Foix, Historiographe des Ordres du Roi, page 287, Volume 3 (Maestricht: Jean-Edme Dupour & Philippe Roux, Imprimeurs-Libraires, associés, 1778).

- ↑ Étienne Baluze, Vitae Paparum Avenionensis, 3 Volumes (Paris, 1693).

- ↑ Pierre Dupuy, Histoire de l'Ordre Militaire des Templiers (Foppens, Brusselles, 1751).

- ↑ "Knights Templar secrets revealed". CNN. October 12, 2007. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071013025546/http://edition.cnn.com/2007/WORLD/europe/10/12/knights.pardon.ap/index.html. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- ↑ Frale, Barbara (2004). "The Chinon chart—Papal absolution to the last Templar, Master Jacques de Molay". Journal of Medieval History. 30 (2): 109–134. doi:10.1016/j.jmedhist.2004.03.004. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- ↑ Martin, p. 58.

- ↑ Barber, New Knighthood (1994), pp. 194–195

- ↑ Finlo Rohrer (October 19, 2007). "What are the Knights Templar up to now?". BBC News Magazine. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/7050713.stm. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- ↑ J.M. Roberts, The Mythology Of The Secret Societies (London: Secker and Warburg, 1972). ISBN 0436420309

- ↑ Peter Partner, The Murdered Magicians: The Templars And Their Myth (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982). ISBN 0192158473

- ↑ John Walliss, Apocalyptic Trajectories: Millenarianism and Violence In The Contemporary World, page 130 (Bern: Peter Lang AG, European Academic Publishers, 2004). ISBN 3-03910-290-7

- ↑ Michael Haag, Templars: History and Myth: From Solomon's Temple To The Freemasons (Profile Books Ltd, 2009). ISBN 978-1-84668-153-0

- ↑ A brief history of Neo-Templarism is given in James R. Lewis (editor), The Order of The Solar Temple: The Temple of Death, pages 20-28 (Ashgate Plublishing Ltd, 2006). ISBN 978-0-7546-5285-4

- ↑ a b c d Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHC - ↑ El-Nasr, Magy Seif. "Assassin's Creed: A Multi-Cultural Read" (PDF). pp. 6–7. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

we interviewed Jade Raymond ... Jade says ... Templar Treasure was ripe for exploring. What did the Templars find

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedTR - ↑ Louis Charpentier, Les Mystères de la Cathédrale de Chartres (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1966), translated The Mysteries of Chartres Cathedral (London: Research Into Lost Knowledge Organisation, 1972).

- ↑ Read, p. 91.

- ↑ Read, p. 171.

- ↑ Martin, p. 139.

- ↑ Sanello, Frank (2003). The Knights Templars: God's Warriors, the Devil's Bankers. Taylor Trade Publishing. pp. 207–208. ISBN 0-87833-302-9.

- ↑ Barber, Trial of the Templars, 1978, p. 62.

- ↑ Martin, p. 133.

- ↑ Karen Ralls, Knights Templar Encyclopedia: The Essential Guide to the People, Places, Events and Symbols of the Order of the Temple, page 156 (The Career Press, Inc., 2007). ISBN 978-156414-926-8

- ↑ Barber, The New Knighthood, p. 332

- ↑ Newman, p. 383

- ↑ Barrett, Jim (Spring 1996). "Science and the Shroud: Microbiology meets archeology in a renewed quest for answers". The Mission. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ↑ Relic, Harry Gove (1996) Icon or Hoax? Carbon Dating the Turin Shroud ISBN 0-7503-0398-0.

- ↑ English translation of the Memorandum in Ian Wilson, The Turin Shroud, p. 230-235 (Victor Gollancz Ltd; 1978 ISBN 0 575 02483 6)

The Massons and the Templars

[edit | edit source]

Freemasonry

[edit | edit source]Since at least the 18th century Freemasonry has incorporated Templar symbols and rituals in a number of Masonic bodies, most notably, the "Order of the Temple" the final order joined in "The United Religious, Military and Masonic Orders of the Temple and of St John of Jerusalem, Palestine, Rhodes and Malta" commonly known as the Knights Templar. One theory of the origins of Freemasonry claims direct descent from the historical Knights Templar through its final fourteenth-century members who took refuge in Scotland, or other countries where the Templar suppression was not enforced. This theory is usually deprecated on grounds of lack of evidence, by both Masonic authorities (See Knights Templar FAQ) and historians (See Freemasonry Today periodical (Issue January 2002) publisher Grand Lodge Publications Ltd).

Cultural References

[edit | edit source]Literature

[edit | edit source]- Foucault's Pendulum (1988) a novel by Umberto Eco, in large part the plot relies in speculation and fiction regarding the Templars.

Paintings

[edit | edit source]Theater

[edit | edit source]Cinema and TV

[edit | edit source]Last Stand of the Templars (4 Apr. 2011) a National Geographic Channel documentary. Featuring a contemporaneous examination of the Battle at Jacob's Fordone, a crucial part of the Templars' past by Dr. Ronnie Ellenblum and his archaeological team.

Ironclad a fictional movie based in the historic facts of 13th-century (1215) England. Portraying Church, Templars and the general English political situation, in particular King John's response to the Magna Carta and the subsequent battle for Rochester Castle.

Forbidden History Season 4 Episode 4, covers the legends and speculations around the Templars with few factual and sourced material in it.