Spanish/Print version

Spanish

[edit | edit source]| This is the print version of Spanish You won't see this message or any elements not part of the book's content when you print or preview this page. |

Main Contents

[edit | edit source]- Introduction

- Lesson one

- Lesson two

- Lesson three

- Lesson four

- Lesson five

- Lesson six

- Pronunciation

- Contributors

Introduction

[edit | edit source]Book definition

[edit | edit source]- Scope: This Wikibook aims to teach the Spanish language from scratch. It will cover all of the major grammar rules, moving slowly and offering exercises and plenty of examples. It's not all grammar though, as it offers vocabulary and phrases too, appealing to all learners.

- Purpose: The purpose of this Wikibook is to teach you the Spanish language in an easy and accessible way. By the end, you should be able to read and write Spanish skillfully, though you'll need a human to help with listening and speaking.

- Audience: Anyone who wishes to learn Spanish, though adult and teenage learners are likely to enjoy it more.

- Organization: This Wikibook requires no prior knowledge of the subject, and all relevant terms are explained as they are encountered. The book runs chronologically from lesson 1 to lesson 2 to lesson 3 and so on until the end.

- Narrative: Generally engaging and thorough, with plenty of examples and exercises to aid learning. Once concepts are introduced, they are repeated, building a base of vocabulary and grammar that will stay in your mind.

- Style: This book is written in British English, and the Spanish taught is generally Iberian Spanish (sometimes called Castellano in Spain), though key Latin American differences are explained as we go along. The formatting is consistent throughout, with Spanish in italics and all tables using the same formatting. Each lesson begins with a conversation, including the key grammar and vocabulary in the lesson. At the end, there is a summary, explaining what has been achieved. Exercises are linked throughout, and each new concept or set of vocabulary is accompanied by examples, each with a translation underneath.

Introduction

[edit | edit source]You are about to embark on a course learning another language, the Spanish language!

The first lesson begins with simple greetings and covers important ideas of Spanish. Throughout education, methods of teaching Spanish have changed greatly. Years ago, the Spanish language was taught simply by memory. Today, however, it is taught by moving slowly and covering grammar and spelling rules.

Again, this is an introduction. If this is the first time you are attempting to learn Spanish, do not become discouraged if you cannot understand, pronounce, or memorize some of the things discussed here.

In addition, learning a second language requires a basic understanding of your own language. You may find, as you study Spanish, that you learn a lot about English as well. At their core, all languages share some simple components like verbs, nouns, adjectives, and plurals. Your first language comes naturally to you and you don't think about things like subject–verb agreement, verb conjugation, or usage of the various tenses; yet, you use these concepts on a daily basis.

While English is described as a very complicated language to learn, many of the distinguishing grammar structures have been simplified over the years. This is not true for many other languages. Following the grammatical conventions of Spanish will be very important, and can actually change the meaning of phrases. You'll see what is meant by this as you learn your first verbs estar and ser.

Do not become discouraged! You can do it.

|

¡Aprovéchalo! |

|

Lesson one

[edit | edit source]

Dialogue

[edit | edit source]- Juanito: ¡Hola! Me llamo Juanito. ¿Cómo te llamas?

- Sofía: Hola, Juanito. Me llamo Sofía. ¿Cómo se escribe tu nombre?

- Juanito: Se escribe J-U-A-N-I-T-O. ¿Qué tal?

- Sofía: Bien. ¿Y tú?

- Juanito: Fenomenal, gracias.

- Sofía: ¡Qué fantástico! Adiós, Juanito.

- Juanito: ¡Hasta luego!

Translation (wait until the end of the lesson).

Hello!

[edit | edit source]| Inglés | Español (help) |

|---|---|

| Hello | Hola (listen) |

| Good morning! | ¡Buenos días! (listen) |

| Good day! | |

| Good afternoon! | ¡Buenas tardes! (listen) |

| Good night! | ¡Buenas noches! (listen) |

| See you later! | ¡Hasta luego! (listen) |

| See you tomorrow! | ¡Hasta mañana! (listen) |

| Goodbye | Adiós (listen) |

- Notes

- Hasta means "until"; luego means "then"; you can translate it as "see you later" or "see you soon". In the same vein, hasta mañana means "see you tomorrow".

- Note the upside-down exclamation (¡) and question marks (¿); you will learn more about them in lesson three.

- Examples

- ¡Buenos días, clase!

- Good morning, class!

- Hola, ¿Cómo están hoy?

- Hello, how are you today?

- Adiós, ¡hasta luego!

- Goodbye, see you later!

What's your name?

[edit | edit source]To ask someone else's name in Spanish, use cómo, then one of the phrases in the table below (¿Cómo te llamas? is "What's your name?" (literally How do you call yourself?). You can also say ¿Cuál es tu nombre? Here the word “cuál” means "which one".

In Spanish, to say your name, you use the reflexive verb llamarse, which means literally to call oneself (Me llamo Juanito is "I call myself Juanito" meaning "My name is Juanito").

| Inglés | Español |

|---|---|

| I am called (I call myself) | Me llamo |

| You (familiar/informal, singular) are called (You call yourself) | Te llamas |

| He/She is called (He/She calls him/herself) | Se llama |

| You (formal, singular) are called (You call yourself) | |

| We are called (We call ourselves) | Nos llamamos |

| You (familiar/informal, plural) are called (You all call yourselves) | Os llamáis |

| They are called (They call themselves) | Se llaman |

| You (formal, plural) are called (You all call yourselves) | |

- Notes

- "Os llamáis" is only used in Spain. In Latin America, "Se llaman" is used for both the second and third plural persons.

- Examples

- Me llamo Juanito

- My name is Juanito (I call myself Juanito.)

- Se llaman Juanito y Robert

- They're called Juanito and Robert. (They call themselves Juanito and Robert.)

- ¿Cómo te llamas?

- What's your name? (What do you call yourself?)

- ¿Cómo se llama?

- What's his/her name? (What does he/she call him/herself?)

Simple vocabulary

[edit | edit source]| Inglés | Español |

|---|---|

| It's a pleasure. | Es un placer. |

| A real pleasure. | Mucho gusto. |

| The pleasure is mine. | El gusto es mío. |

| How are you? | ¿Qué tal? (listen) |

| ¿Cómo estás? | |

| Great! | Fantástico |

| Fantástica | |

| Great | Genial |

| Very well | Muy bien |

| Well | Bien |

| So-so | Más o menos |

| Bad | Mal |

| Really bad | Fatal |

| And you? | ¿Y tú? |

| Thank you | Gracias (listen) |

| Thank you very much | Muchas gracias |

| You're welcome | De nada

con mucho gusto gusto |

| Yes | Sí |

| No | No |

- Notes

For some of the words above, there are two options. The one ending in "o" is for males, and the one ending in "a" is for females. It's all to do with agreement, which is covered in future chapters.

Also, there are cultural differences in how people respond to "How are you?". In the U.S., we might answer "mal" if we have a headache, or we're having a bad hair day. In Spanish-speaking cultures, "mal" would be used if a family member were very ill, or somebody lost their job. Similarly, "fatal" in the U.S. might mean a ruined manicure or a fight with one´s girlfriend, but would be reserved more for things like losing one's home in a Spanish-speaking country.

Expressing "you are welcome" is more formal in Costa Rica than in other countries. Con mucho gusto is formal. Gusto is less formal. De nada, in some areas is considered slightly insulting and should not be used.

Examples

- Juanito: Hola, Rosa. ¿Qué tal?

- Hello, Rosa. How are you?

- Rosa: Muy bien, gracias. ¿Y tú, Juanito?

- Very well, thanks. And you, Juanito?

- Juanito: Bien también. ¡Hasta luego!

- I'm good too. See you later!

The Spanish alphabet

[edit | edit source]Here is the traditional Spanish alphabet. The current Spanish alphabet is made up of the letters with numbers above them, and is also sorted in that order. Please read the notes and sections below. (Blue and red letters are a part of the normal English alphabet).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | ch | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | ll | m | n | ñ | o | p | q | r | rr | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z |

| Notes about Ñ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

N and Ñ are considered two different letters. They are alphabetized as separate letters, so Ñ always comes after N, regardless of where it appears in the word. Ex: muñeca comes after municipal. It is extremely rare for words to begin with Ñ—the only common example is ñoñear (to whine). Like the digraphs mentioned below, Ñ originally began as NN but morphed into a squiggle that was placed above a standard N to save space when writing. The character ~ is independently known as a tilde in English; tilde in Spanish can generally refer to any diacritic that modifies letters (such as the very common acute accent: ´) and the specific word for the tilde is virgulilla. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes about CH, LL, and RR | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

CH and LL are no longer distinct letters of the alphabet. In 1994, the Real Academia Española (Spanish Royal Academy) declared that they should be treated as digraphs for collation purposes. Accordingly, words beginning with CH and LL are now alphabetized under C and L, respectively. In 2010, the Real Academia Española declared that CH and LL would no longer be treated as letters, bringing the total number of letters of the alphabet down to 27. In even more rare and archaic sources, RR was treated as a single letter but was never the beginning of a word. It is still treated as a separate letter in the Filipino creole language Chavacano, which is based on Spanish. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes about K and W | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

K and W are part of the alphabet but are mostly seen in foreign-derived words and names, such as karate and whiskey. For instance, kilo is commonly used to refer to a kilogram. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Consonants

[edit | edit source]Although the above will help you understand, proper pronunciation of Spanish consonants is a bit more complicated:

Most of the consonants are pronounced as they are in American English with these exceptions:

- b like the English b at the start of a word and after m or n, (IPA: /b/). Elsewhere in a word, especially between vowels, it is softer, often like a blend between English v and b. (IPA: /β/ or /b/)

- c before i and e like English th in "think" (in Latin America it is like English s) (European IPA: /θ/; Latin American IPA: /s/)

- c before a, o, u and other consonants, like English k (IPA: /k/)

- The same sound for e and i is written like que and qui, where the u is silent (IPA: /ke/ and /ki/).

- ch like ch in “cheese” (IPA: /tʃ/)

- d at the start of a word and after n, like English d in "under" (IPA: /d/)

- d between vowels (even if these vowels belong to different words) similar to English th in "mother" (IPA: /ð/); at the end of words like "universidad" you may hear a similar sound, too.

- g before e or i, like ch in "Chanukah" or "Challah" (IPA: /x/)

- g before a, o, u, like g in “get” (IPA: /g/)

- The same sound for e and i is written like gue and gui, where the u is silent (IPA: /ge/ and /gi/). If the word needs the u to be pronounced, you write it with a diaeresis e.g. pingüino, lengüeta.

- h is always silent, except in the digraph ch and some very rare loan words, such as hip hop. So the Central American state of Honduras is pronounced exactly the same is if it were spelled “Onduras”: (IPA: /onˈduɾas/, [õn̪ˈd̪uɾas])

- j like the h in hotel, or like the Scottish pronunciation of ch in "loch" (IPA: /h/ or /x/)

- ll is pronounced like gli in Italian "famiglia," or as English y in “yes” (IPA: /ʎ/)

- In some Latin American countries, ll is pronounced differently. For instance, in Argentina, ll is pronounced like s in English "vision" (IPA: /ʒ/); in Chile, ll is pronounced like sh in English "shoe" (IPA: /ʃ/)

- ñ like nio in “onion” (or gn in French "cognac" or Italian "gnocchi") (IPA: /ɲ/)

- q like the English k; occurs only before ue or ui (IPA: /k/)

- r at the beginning of a word; after l, n, or s; or when doubled (rr), it is pronounced as a full trill (IPA: /r/), elsewhere it is a single-tap trill (IPA: /ɾ/)

- v is pronounced like the softer form of the Spanish b. (IPA: /b/)

- x is pronounced much like an English x, except a little more softly, and often more like gs. (IPA: /ks/)

- z like the English th (in Latin America, like the English s) (European IPA: /θ/; Latin American IPA: /s/)

Vowels

[edit | edit source]The pronunciation of vowels is as follows:

- a [a] "La mano" as in "Kahn" (ah)

- e [e] "Mente" as in "hen" (eh)

- i [i] "Sin" as the ea in "lean" (e)

- o [o] "Como" as in "more" (without the following 'r')

- u [u] "Lunes" as in "toon" or "loom" (oo)

The "u" is always silent after a g or a q (as in "qué" pronounced keh).

Spanish also uses the ¨ (diaeresis) diacritic mark over the vowel u to indicate that it is pronounced separately in places where it would normally be silent. For example, in words such as vergüenza ("shame") or pingüino ("penguin"), the u is pronounced as in the English "w" and so forms a diphthong with the following vowel: [we] and [wi] respectively. It is also used to preserve sound in stem changes and in commands: averiguar (to research) - averigüemos (let's research).

The y [ʝ] "Reyes" is similar to the y of "yet", but more voiced (in some parts of Latin America it is pronounced as s in "vision" [ʒ] or sh in "flash" [ʃ]) At the end of a word or when it means "and" ("y") it is pronounced like i.

Word stress and acute accents

[edit | edit source]Spanish words ending in a consonant other than n or s are stressed on the last syllable: paRED (wall), efiCAZ (effective).

Words ending in a vowel, n, or s are stressed on the next to the last syllable: TEcho (roof), desCANso (rest).

Words which break either of the above rules must have an accent mark (´, the acute accent) indicating the stressed syllable: anDÉN (platform), haBLÓ (he spoke), pájaro (bird).

The same letters, pronounced with stress on a different syllable, can constitute a different word. For example, the word ánimo, with stress on the first syllable, is a noun meaning "mood" or "spirit." Animo, with stressed on ni, is a verb meaning "I cheer." And animó is stressed on mó is a verb meaning "he cheered."

Monosyllables do not need accent marks – there is no need to mark the stressed syllable. However, the accent mark is used to distinguish between homographs, which are different words written with the same letters: sí (yes), si (if); tú (you, subject pronoun), tu (your, possessive adjective), él (he/him) & el (the). It is used on interrogative words, distinguishing them from in relative pronoun pairs: cómo (how?) & como (as), dónde (where?) & donde (where).

| A | E | I | O | U |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| á | é | í | ó | ú |

How do you spell that?

[edit | edit source]| Inglés | Español |

|---|---|

| How is it spelled? | ¿Cómo se deletrea? |

| ¿Cómo se escribe? | |

| It is spelled | Se escribe |

| B as in Barcelona | Con B de Barcelona |

- Examples

- Juanito: Buenos días. Me llamo Juanito. ¿Cómo te llamas?

- Good day. My name is Juanito. What's your name?

- Roberto: Hola. Me llamo Roberto. ¿Cómo se escribe Juanito?

- Hello. I'm Robert. How do you spell Juanito?

- Juanito: Se escribe J (Jota); U (U); A (A); N (ene); I (i); T (te); O (o).

Summary

[edit | edit source]In this lesson, you have learned

- How to greet people (Hola; buenos días; adiós).

- How to introduce yourself (Me llamo Juanito).

- How to introduce others (Se llama Roberto).

- How to say how you are (Fenomenal; fatal; bien).

- How to spell your name (Se escribe J-U-A-N-I-T-O).

- How to ask others about any of the above (¿Cómo te llamas?; ¿Cómo estás?; ¿Cómo se escribe?).

- The Spanish Alphabet and how letters are pronounced.

You should now do the exercise related to each section (found here), and translate the dialogue at the top before moving on to lesson 2...

Drill the words covered in this lesson with this Flashcard Exchange deck.

|

¡Aprovéchalo! |

|

Lesson two

[edit | edit source]

Dialogue

[edit | edit source]- Raúl: ¡Hola, Sofía! Me llamo Raúl. ¿Cuál es la fecha de hoy?

- Sofía: Hola, Raúl. Hoy es el diecisiete de octubre.

- Raúl: Muchas gracias. Mi cumpleaños es el viernes.

- Sofía: ¡Feliz cumpleaños!

- Raúl: Gracias. ¿Cuántos años tienes?

- Sofía: Tengo veinte años.

- Raúl: Vale. Adiós, Sofía.

- Sofía: ¡Hasta luego!

Translation (wait until the end of the lesson).

The numbers

[edit | edit source]

| 0. | Cero | ||||||||||||

| 1. | Uno | 11. | Once | 21. | Veintiuno | 31. | Treinta y uno | 50. | Cincuenta | 600. | Seiscientos | ||

| 2. | Dos | 12. | Doce | 22. | Veintidós | 32. | Treinta y dos | 60. | Sesenta | 700. | Setecientos | ||

| 3. | Tres | 13. | Trece | 23. | Veintitrés | 33. | Treinta y tres | 70. | Setenta | 800. | Ochocientos | ||

| 4. | Cuatro | 14. | Catorce | 24. | Veinticuatro | 34. | Treinta y cuatro | 80. | Ochenta | 900. | Novecientos | ||

| 5. | Cinco | 15. | Quince | 25. | Veinticinco | 35. | Treinta y cinco | 90. | Noventa | 1,000. | Mil | ||

| 6. | Seis | 16. | Dieciséis | 26. | Veintiséis | 36. | Treinta y seis | 100. | Cien | 2,000. | Dos mil | ||

| 7. | Siete | 17. | Diecisiete | 27. | Veintisiete | 37. | Treinta y siete | 200. | Doscientos | 10,000. | Diez mil | ||

| 8. | Ocho | 18. | Dieciocho | 28. | Veintiocho | 38. | Treinta y ocho | 300. | Trescientos | 100,000. | Cien mil | ||

| 9. | Nueve | 19. | Diecinueve | 29. | Veintinueve | 39. | Treinta y nueve | 400. | Cuatrocientos | 101,000. | Ciento un mil | ||

| 10. | Diez | 20. | Veinte | 30. | Treinta | 40. | Cuarenta | 500. | Quinientos | 1,000,000. | Un millón |

Notes

[edit | edit source]- To form the numbers from thirty to one hundred, you take the multiple of ten below it, then y, then its units value:

"54" Cincuenta y cuatro Like, fifty and four

"72" Setenta y dos Like, seventy and two

"87" Ochenta y siete Like, eighty and seven

- To say one hundred you say just cien, never un cien. To form the numbers from one hundred to two hundred, you turn cien into ciento before adding the rest of the number:

"101" Ciento uno

"128" Ciento veintiocho

"150" Ciento cincuenta

"199" Ciento noventa y nueve

- For numbers between 200 and 900, use the plural "s" (doscientos, ochocientos). Also beware of the usage of these numbers with feminine nouns like the old Spanish currency "peseta". You need to use the feminine agreement then: doscientas pesetas. That agreement has to be observed even when it's in the middle of the number: doscientas veinticinco pesetas.

- When used before a masculine noun, uno becomes un; before a feminine noun, una. To preserve the stress on the last syllable, veintiuno acquires an acute accent when it becomes veintiún before a masculine noun. Note the same mechanism in operation when writing 16 (diez + seis) = dieciséis or 22 (veinte + dos) = veintidós.

- Spanish uses the long count style:

1,000,000,000 mil millones / un millardo (less common)

1,000,000,000,000 un billón

1,000,000,000,000,000 mil billones / un billardo (rare)

1,000,000,000,000,000,000 un trillón

1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 mil trillones / un trillardo (rare)

1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 un cuatrillón

The rule of thumb is to count how many "millions" are in the digits:

1 (000 000) (000 000) (000 000) is un trillón, because there are three ("tri") multiples of millions.

- Longer numbers:

12,521,008,867,121,403,051 Doce trillones quinientos veintiún mil ocho billones ochocientos sesenta y siete mil ciento veintiún millones cuatrocientos tres mil cincuenta y uno

68,076,564,322,676,958,606 Sesenta y ocho trillones setenta y seis mil quinientos sesenta y cuatro billones trescientos veintidós mil seiscientos setenta y seis millones novecientos cincuenta y ocho mil seiscientos seis

Note that the words millones, billones, trillones are written in plural, but mil (thousand) is always kept in singular, even when counting several thousands. However, if you need to refer to an amount in several thousands without specifying how many, you can use the plural miles (He escrito miles de cartas = I've written thousands of letters). For this same purpose, you can use the synonym millares.

Similarly, there is the plural cientos (He escrito cientos de cartas = I've written hundreds of letters). Centenas and centenares are less common synonyms for cientos.

All those synonyms have forms in singular (Un millar de cartas = One thousand letters; Una centena / Un centenar de cartas = One hundred letters). These synonyms are not used for actually counting, though.

There is also decena, which means a group of ten.

Examples

[edit | edit source]- Tengo diecisiete gatos

- I have 17 cats.

- Hay treinta y cinco aulas

- There are 35 classrooms.

- Tengo noventa y seis primos.

- I have 96 cousins.

- Hay once estudiantes en la clase de español.

- There are 11 students in the spanish class.

- ¡Quiero un caramelo!

- I want a candy!

- ¡Quiero uno!

- I want one!

To declare the presence or existence of something (e.g. "there is," "there are"), Spanish uses hay, which is a special conjugation of the verb haber (to have). Its past form ("there was," "there were") is hubo. Another form in the past (meaning roughly "there used to be") is había. Its future form ("there will be") is habrá. All these forms are invariable in singular and plural: Había un gato aquí, Había dos gatos aquí. Attempting to construct plural forms of them ("habían", "habrán") is a very common error and is severely frowned upon.

How old are you?

[edit | edit source]To ask someone else's age in Spanish, use Cuántos años, then one of the entries in the table below (¿Cuántos años tienes? means "How old are you?", or more literally, "How many years do you have?")

To say your age in Spanish, you use the irregular verb tener (which means "to have"), then your age, then años (which means "years"). For example, Tengo trece años means "I have 13 years" or "I am 13 years old".

| Inglés | Español |

|---|---|

| I have | (Yo) Tengo |

| You (familiar, singular) have | (Tú) Tienes |

| He/She/You (formal, singular)/It has | (Él/Ella/Usted) Tiene |

| We have | (Nosotros) Tenemos |

| You (familar, plural) have | (Vosotros) Tenéis |

| They/You (formal, plural) have | (Ellos/Ellas/Ustedes) Tienen |

- Note

- "Tenéis" would only be used in Spain. In Latin America, one would use "Tienen" for both the second and third plural persons.

- Examples

- Tengo veinte años

- I am 20 years old.

- ¿Cuántos años tienes?

- How old are you?

- Tiene ochenta y siete años.

- He is 87 years old.

- ¿Cuántos años tienen?

- How old are they?

What's the date today?

[edit | edit source]To ask for the date in Spanish, you use ¿Cuál es la fecha? or ¿Qué día es hoy? (meaning "What is the date?", or "What day is today?"). In reply, you would say Hoy es [day of the week], [date of the month] de [month of the year] (For example, Hoy es martes veinticinco de mayo is "Today is Tuesday, the 25th of May").

- Notes

- Neither days of the week nor months of the year are capitalised, unless at the beginning of sentences.

- On the first of the month, some Spanish speakers say primero [First] (Hoy es domingo primero de enero).

- You may still find the spelling setiembre in books from the early 20th century. It emerged from the way some countries pronounce the consonants in it. This spelling is not standard usage and you should avoid using it.

- Examples

- ¿Qué fecha es hoy? (¿A qué estamos? is used too.)

- What is the date?

- Hoy es miércoles veintinueve de septiembre.

- Today is Wednesday, the 29th of September

- Hoy es jueves quince de agosto.

- Today is Thursday, the 15th of August.

- Hoy es sábado dos de enero.

- Today is Saturday, the 2nd of January.

When's your birthday?

[edit | edit source]Although birthday translates as cumpleaños, they do not imply the same exact meaning. In English, birthday literally refers to the day of your birth, so it is possible to wish happy birthday to a newborn. In Spanish, cumpleaños literally means "completing a year" and is only used for the day in subsequent years that matches the date on which you were born. Thus, you would never say "feliz cumpleaños" to a newborn, since he still hasn't "completed a year."

| Inglés | Español |

|---|---|

| When is your birthday? | ¿Cuándo es tu cumpleaños? |

| My birthday is | Mi cumpleaños es |

| On the first of May | El primero de mayo |

| On Wednesday | El miércoles |

| Happy birthday! | ¡Feliz cumpleaños! |

- Examples

- Mi cumpleaños es el once de julio.

- My birthday is on the 11th of July.

- Mi cumpleaños es el ocho de diciembre.

- My birthday is on the 8th of December.

- ¿Cuándo es tu cumpleaños?

- When is your birthday?

- Mi cumpleaños es el sábado.

- My birthday is on Saturday.

Summary

[edit | edit source]In this lesson, you have learned:

- How to count from cero to one septillion (cero; veintiocho; noventa; cien; un cuatrillón)

- The days of the week (lunes; miércoles; viernes)

- The months of the year (enero; abril; octubre; diciembre)

- How to say your age (Tengo cuarenta años)

- How to ask the age of others (¿Cuántos años tienes?)

- How to say today's date (Hoy es jueves veintinueve de noviembre)

- How to say your birthday (Mi cumpleaños es el primero de agosto; mi cumpleaños es el martes)

- How to ask the birthday of others (¿Cuándo es tu cumpleaños?)

You should now do the exercise related to each section (found here), and translate the dialogue at the top before moving on to lesson 3...

|

¡Aprovéchalo! |

|

Lesson three

[edit | edit source]

Articles

[edit | edit source]As in many languages, every noun in Spanish has a gender: it is either masculine or feminine. For example, gato ("cat") is masculine and mesa (table) is feminine. Almost all nouns ending in -o are masculine, most words ending in -a are feminine. The gender of unliving things is arbitrary and must be memorized, or looked up. Do not try to figure out what is "feminine" about the word mesa; it doesn't work that way.

In English we have two types of articles: the definite article ("the") and the indefinite article ("a" or "an"). Spanish does too, but there are 4 forms of each, depending on the number and gender of the noun.

Definite articles

[edit | edit source]|

Spanish Grammar • Print version

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | singular | el | el hombre | the man |

| plural | los | los niños | the boys | |

| feminine | singular | la | la mujer | the woman |

| plural | las | las niñas | the girls | |

Indefinite articles

[edit | edit source]|

Spanish Grammar • Print version

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | singular | un | un hombre | a man |

| plural | unos | unos niños | some boys | |

| feminine | singular | una | una mujer | a woman |

| plural | unas | unas niñas | some girls | |

When we want to turn a noun into plural, we follow these rules:

- If the noun ends in a vowel add -s Example: un gato (a cat); unos gatos - (some cats).

- If the noun ends in a consonant add -es. Example: el papel (the sheet of paper); los papeles (the sheets of paper).

Fortunately, the gender of Spanish nouns is usually pretty easy to work out. Some very simple rules-of-thumb:

- If a noun ends in a, it's likely to be feminine. Example: bolsa (bag).

- If it ends in o, or a consonant, it's likely to be masculine. Examples: libro (book), móvil (mobile phone).

There are some exceptions though, but you will learn these as you attain new vocabulary.

Go to the exercises.

Regular Verbs

[edit | edit source]We have already seen the present tense conjugations of two Spanish verbs, llamarse and tener. However, tener (to have) is an irregular verb. Luckily, many verbs follow an easy to understand conjugation scheme.

In Spanish, the conjugation of a regular verb depends on the ending of its infinitive. (The infinitive is the basic form of the verb that you find in the dictionary; for example, English infinitives are always written with to, like the verbs to run or to speak.) All Spanish infinitives end in the letter r, and the three regular conjugation patterns are classified into -ar, -er, and -ir verbs.

Unlike English, Spanish verbs conjugate depending on the person; that is, they change depending on who is being talked about. This occurs in the English verb to be (e.g. I am, you are, he is, etc.) but in Spanish this occurs for all persons in all verbs. As a result, pronouns are usually omitted because they can be inferred from the conjugation.

- The pronouns

| Person in English | Person in Spanish | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| First | I | We | Yo | Nosotros |

| Second | You | You all | Tú | Vosotros |

| Third | He / She / It | They | Él / Ella Usted |

Ellos / Ellas Ustedes |

Spanish distinguishes between the singular you (informal tú, formal usted) and the plural you (informal vosotros, formal ustedes). Both tú and vosotros have their own conjugation patterns; usted follows the same pattern as él/ella and ustedes follows the same pattern as ellos.

In Latin America, vosotros is almost unheard of, and ustedes is exclusively used instead.

Nosotros (we) has a feminine nosotras that is used when the entire group is composed of females. Likewise, vosotros and ellos have feminine forms vosotras and ellas.

- The Present Tense in English

| Present Tense (en) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |

| First | I play | We play |

| Second | You play | You all play |

| Third | He / She / It plays | They play |

- The Present Tense in Spanish

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- More examples

- Llorar ("to cry"): lloro, lloras, llora, lloramos, lloráis, lloran

- Cocinar ("to cook"): cocino, cocinas, cocina, cocinamos, cocináis, cocinan

- Beber ("to drink"): bebo, bebes, bebe, bebemos, bebéis, beben

- Comer ("to eat"): como, comes, come, comemos, coméis, comen

- Deber ("to ought to do, to owe"): debo, debes, debe, debemos, debéis, deben

- Leer ("to read"): leo, lees, lee, leemos, leéis, leen

- Asistir ("to attend"): asisto, asistes, asiste, asistimos, asistís, asisten

- Cubrir ("to cover"): cubro, cubres, cubre, cubrimos, cubrís, cubren

- Escribir ("to write"): escribo, escribes, escribe, escribimos, escribís, escriben

- Vivir ("to live"): vivo, vives, vive, vivimos, vivís, viven

- Notes

- There are many more "-ar" verbs than "-er" or "-ir". Make sure you are most familiar with these endings.

- The second person plural is highlighted because that tense is only used in the variety of Spanish used in Spain. In other Spanish dialects the third person plural form is used instead.

- When reading texts, you will need to know the person of the verb at a glance. Notice the pattern:

- "O" denotes I

- "S" denotes You

- A vowel that is not "O" denotes He/She/It

- "MOS" denotes We

- "IS" denotes You All

- "N" denotes They

Questions and exclamations

[edit | edit source]In previous lessons, you will have noticed that we used an upside-down question mark "¿". In Spanish, questions always begin with it, finishing with the usual question mark. It is the same for exclamations; the upside-down exclamation mark "¡" precedes exclamations. Spanish is the only language with these two inverted characters.

This happens because Spanish does not reverse the word order to ask a question. While English says You are here / Are you here?, Spanish keeps the same order: Tú estás aquí / ¿Tú estás aquí? Whereas the English word order alerts you from the beginning that what you are going to read is a question, Spanish offers no such initial warning. To compensate for this, Spanish adds the initial question mark, so that you'll always be able to tell a declarative statement from a question from the moment you begin reading it.

Questions in Spanish are mainly done by intonation (raising the voice at the end of the question), since questions are often identical to statements. Te llamas Richard means "Your name is Richard", and ¿Te llamas Richard? means "Is your name Richard?".

You can also use question words, as indicated below.

| Español | Inglés |

|---|---|

| ¿Dónde? | Where? |

| ¿Quién? | Who? |

| ¿Qué? | What? |

| ¿Cuál? | Which? |

| ¿Cómo? | How? (as in How does it work?) |

| ¿Cuán? | How? (as in How long is it?) |

| ¿Por qué? | Why? |

| ¿Cuándo? | When? |

| ¿Cuánto? | How much? |

| ¿Cuántos? | How many? |

| ¿De quién? | Whose? |

| ¿A quién? | Whom? |

| ¿De dónde? | Whence? |

| ¿Adónde? | Whither? |

| ¿Para qué? | Wherefore? |

- Examples

- ¿Con quién?

- With whom?

- ¿Dónde está el banco?

- Where is the bank?

- ¿Cuándo es tu cumpleaños?

- When's your birthday?

- ¿Qué fecha es hoy?

- What is the date today?

- Notes

- If you refer to a group of people, you can use the plural quiénes.

- Cuánto and cuántos have feminine forms cuánta and cuántas.

- The archaic cúyo was used in place of de quién. You may still find it in books from the early 20th century. Outside of questions, the corresponding pronoun cuyo is still used to mean whose in declarative statements. (Feminine cuya; plural cuyos; feminine plural cuyas; this pronoun's number and gender agree with that which is possessed, not the possessor.)

- Cuán is gradually becoming archaic and being replaced by qué tan.

Summary

[edit | edit source]In this lesson, you have learned:

- The Spanish articles (el; la; los; las; un; una; unos; unas).

- How to conjugate regular verbs in the present tense (lloro; comes; vive; cocinamos; bebéis; cubren).

- How to question people and exclaim in Spanish (¿Cuántos años tienes?; ¡Qué fantástico!)

You should now do the exercise related to each section (found here) before moving on. This is a very important topic for future lessons; it is important that you know it well.

You have now completed this chapter! Return to the Contents...

|

¡Aprovéchalo! |

|

Lesson four

[edit | edit source]

Dialogue

[edit | edit source]| Vocabulary | |

|---|---|

| Londres | London |

| Pero | But |

| Pues | Well |

- Raúl: ¡Hola! ¿Dónde vives?

- Sofía: Hola, Raúl. Vivo en un piso en Londres, Inglaterra. ¿Y tú?

- Raúl: Vale. Vivo en el sur de España.

- Sofía: ¿En el campo o en la ciudad?

- Raúl: En el campo. Las ciudades son ruidosas.

- Sofía: Sí, pero no hay nada que hacer en el campo.

- Raúl: Pues, ¡adiós, Sofía!

- Sofía: ¡Hasta luego!

Translation (wait until the end of the lesson).

Countries of the World

[edit | edit source] |

||||

| El Reino Unido | Inglaterra | Escocia | Gales | Irlanda |

|

|

|

| |

| España | Francia | Alemania | Italia | Rusia |

| Los Estados Unidos | Canadá | Nueva Zelanda | Australia | México |

|

|

|

|

|

| Japón | China | India | Brasil | Turquía |

|

|

|

|

|

| Portugal | Marruecos | Egipto | Sudáfrica | Argentina |

|

|

| ||

| Corea del Sur | Filipinas | Singapur | Malasia | Indonesia |

Where do you live?

[edit | edit source]To say you are from a country, you use ser (meaning "to be [a permanent characteristic]"), then de (meaning "of" or "from"), then the country or place. To say you are currently living in a place or country, you use vivir (meaning "to live"), then en (meaning "in"), then the country or place.

To ask where someone else lives, you use Dónde then vivir (¿Dónde vives? means "Where do you live?"). To ask where someone is from, you use De dónde, then ser (¿De dónde eres? means "Where are you from?").

While vivir is totally regular (vivo, vives, vive, vivimos, vivís, viven), ser is about as irregular as they come. It is conjugated below.

| Inglés | Español |

|---|---|

| I am | Soy |

| You are | Eres |

| He/She/It is | Es |

| We are | Somos |

| You all are | Sois |

| They are | Son |

- Examples

- Vivo en Inglaterra

- I live in England.

- Son de España, pero viven en Alemania.

- They are from Spain, but they live in Germany.

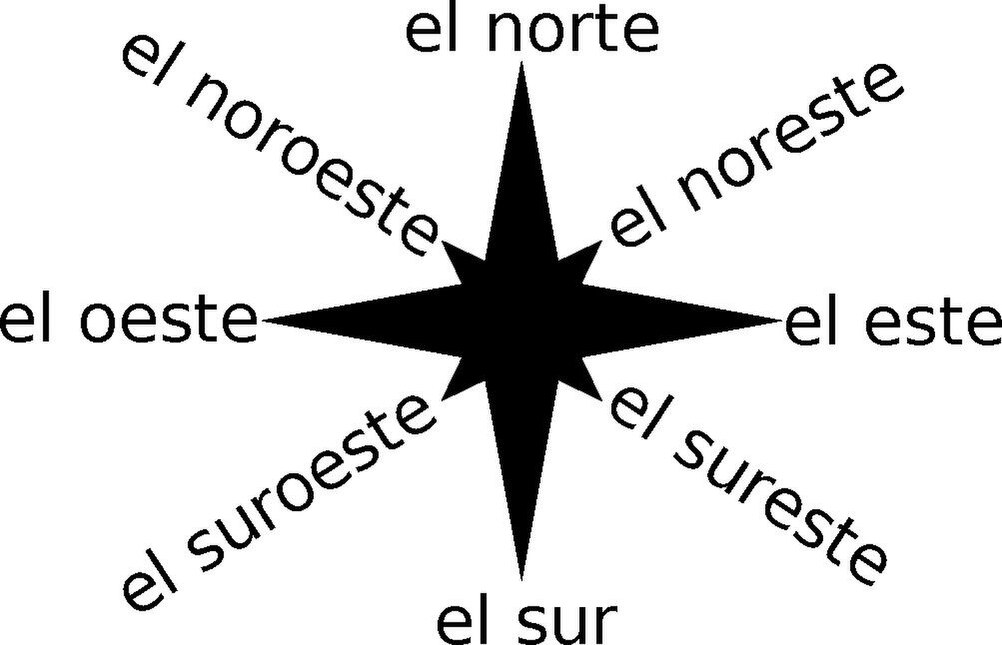

The compass

[edit | edit source]- Examples

- Vivo en el suroeste de México.

- I live in the Southwest of Mexico.

- Soy del norte de Australia.

- I'm from the north of Australia.

- Notes

- Noreste has a variant nordeste. Sureste and suroeste have, respectively, variants sudeste and sudoeste.

- Oeste has a synonym occidente which is used with the same frequency. The corresponding synonym of este is oriente. You can also use them in compounds like nororiente, noroccidente, suroriente/sudoriente and suroccidente/sudoccidente.

- Their corresponding adjectives are septentrional (northern), meridional (southern), oriental (eastern), occidental (western). Compound adjectives like noroccidental and sudoriental are also possible.

- The adjectives norteño (northern) and sureño (southern) do not refer to geographical positions but to someone's regional origin.

- Archaic usage had septentrión to mean north and mediodía to mean south. Some older books may still use them. Today, septentrión is no longer used, and mediodía means noon.

Housing

[edit | edit source]| Inglés | Español |

|---|---|

| A house | Una casa |

| A detached house | Una casa individual |

| A semi-detached house | Una casa pareado |

| A terraced house | Una casa adosada |

| A flat | Un piso |

| A bungalow | Un bungalow |

| A room | Una habitación |

- Note

The singular is una habitación, but the plural is unas habitaciones (without the accent)

- This is a general rule, because in the singular, the 'ó' shows the sound is to be emphasized, but for plural the 's' has also to be heard, so it is written as it is spoken, as 'o' without the accent).

- Examples

- Vivo en un piso.

- I live in a flat.

- Vivo en una casa adosada en Canadá.

- I live in a semi-detached house in Canada.

- Vive en un bungalow que tiene diez habitaciones.

- He lives in a bungalow that has ten rooms.

Adjectives

[edit | edit source]As we already learned, Spanish nouns each have a gender. This doesn't just affect the article, but the adjective; it has to agree. Also, adjectives go after the noun, not before it.

If the adjective (in its natural form - the form found in the dictionary), ends in an "O" or an "A", then you remove that vowel and add...

|

|

- O for masculine singular nouns

- OS for masculine plural nouns

- A for feminine singular nouns

- AS for feminine plural nouns.

- Examples

- Un hombre bueno

- A good man

- Unos hombres buenos

- Some good men

- Una mujer buena

- A good woman

- Unas mujeres buenas

- Some good women

The masculine O / feminine A rule is applicable to the vast majority of Spanish nouns. There are a handful of exceptions, though, but you'll get to memorize them.

City and Countryside

[edit | edit source] |

|

|

Spanish Vocabulary • Print version

| |

|---|---|

| Inglés | Español |

| The city | La ciudad |

| The countryside | El campo |

| The good thing about ... is that | Lo bueno de ... es que |

| The bad thing about ... is that | Lo malo de ... es que |

| There are lots of things to do | Hay mucho que hacer |

| There isn't anything to do | No hay nada que hacer |

| You can walk in woodlands | Se puede caminar en los bosques |

| There isn't any foliage | No queda ningún follaje |

| Pretty | Bonito/a |

| Lively | Animado/a |

| Quiet | Tranquilo/a |

| Boring | Aburrido/a |

| Noisy | Ruidoso/a |

- Examples

- La ciudad es ruidosa.

- The city is noisy.

- El campo es aburrido.

- The countryside is boring.

- Lo bueno de la ciudad es que hay mucho que hacer.

- The good thing about the city is that there are lots of the things to do.

- Lo malo de la ciudad es que no quedan plantas.

- The bad thing about the city is that there isn't any foliage.

Lo is the only Spanish word classified as neuter gender (although it is always accompanied by masculine adjectives). It is an unusual article that does not carry a noun, and is used to build sentences like esto es lo que yo quiero (this is what I want) and haz lo correcto (do the right [thing]), used to turn an adjective or adverb into a substantive. For this purpose, it's clearly demonstrated in this example: "lo peor ya pasó" (the worse [situation or thing] already had pass).

Summary

[edit | edit source]In this lesson, you have learned

- Various countries of the world (Australia; Italia; Francia; los Estados Unidos).

- How to say where you and others live and come from (Vivo en Inglaterra; Somos de Gales).

- How to ask where someone lives (¿Dónde vives?).

- The points of the compass (el sur; el noroeste; el oeste).

- How to describe your house (una casa; un piso).

- The basics of adjectives ending in "O" or "A" (la mujer mala; el niño bonito).

- How to talk about the city or the countryside (la ciudad; el campo; no hay mucho para hacer).

You should now do the exercise related to each section (found here), and translate the dialogue at the top before moving on to lesson 5...

|

¡Aprovéchalo! |

|

Lesson five

[edit | edit source]

Dialogue

[edit | edit source]| Vocabulary | |

|---|---|

| Todo el tiempo | All the time |

| ¡Hasta mañana! | See you tomorrow! |

| Divertido | Fun |

- Raúl: ¡Hola, Sofía! ¿Te gustan los deportes?

- Sofía: Buenos días. Me encanta jugar al fútbol. ¿Y tú?

- Raúl: No, no me gusta. Sin embargo, practico natación todo el tiempo/siempre.

- Sofía: Ah, no sé nadar. ¿Juegas al ajedrez?

- Raúl: Sí, me encanta; es un juego muy divertido.

- Sofía: ¡Adiós, Raúl!

- Raúl: ¡Hasta mañana!

Translation (wait until the end of the lesson).

Sports and Activities

[edit | edit source]|

Spanish Vocabulary • Print version

| |

|---|---|

| Inglés | Español |

| A sport | Un deporte |

| A game | Un juego |

| An activity | Una actividad |

| To play (a game) | Jugar |

| To play (an instrument) | Tocar |

| To practice | Practicar |

| Soccer | El fútbol |

| American football | El fútbol americano |

| Rugby | El rugby |

| Tennis | El tenis |

| Cricket | El críquet |

| Swimming | La natación |

| Judo | El judo |

| Chess | El ajedrez |

| To sing | Cantar |

| To read | Leer |

| To swim | Nadar |

| To watch TV | Ver la tele |

| A lot | Mucho |

| Many | Muchos |

- Notes

- In Spanish, if an activity is a game, then you "play" it (jugar), otherwise you "practice" it (practicar). For example, it's jugar al tenis ("to play tennis") but practicar la natación ("to go swimming").

- If someone plays an instrument you use the verb tocar. For example, tocar la guitarra ("to play the guitar")

- The verbs are all regular, except:

- Jugar (this is discussed in detail below)

- Ver (veo, ves, ve, vemos, veis, ven)

- Examples

- Veo mucho la tele.

- I watch TV a lot

- Practico natación.

- I go swimming.

- ¿Practicas judo?

- Do you do judo?

- Practicamos muchas actividades.

- We do many activites

- ¿Por qué cantáis?

- Why do you sing?

- ¿Cuándo lee?

- When does he or she read?

Stem-changing Verbs

[edit | edit source]Jugar the first type of irregular verb; known as a stem-changing verb. Basically, in the "I", "you", "he/she/it" and "they" forms, the u or o changes to a ue. The jugar example is written out below.

| Inglés | Español |

|---|---|

| I | Juego |

| You | Juegas |

| He/She/It | Juega |

| We | Jugamos |

| You all | Jugáis |

| They | Juegan |

- Other verbs that follow this pattern

- poder ("to be able to"): puedo, puedes, puede, podemos, podéis, pueden

- dormir ("to sleep"): duermo, duermes, duerme, dormimos, dormís, duermen

- encontrar ("to find"): encuentro, encuentras, encuentra, encontramos, encontráis, encuentran

- Notes

- The verb jugar always has a after it: jugar a. In Spanish, a el gets contracted to al and de el gets contracted to del. So, it would be juego al rugby.

- Poder (meaning "to be able to") is usually followed by another verb, making "I can do something". The following verb must be in the infinitive. For example, puede leer ("he can read").

- Examples

- Juego al tenis.

- I play tennis.

- ¿Jugáis al ajedrez?

- Do you play chess?

- ¿Qué deportes juegas?

- What sports do you play?

- ¿Cuándo juegan al fútbol?

- When do they play football?

- ¿Puedes cantar?

- Can you sing?

- ¿Dónde duermes?

- Where do you sleep?

Compound Sentences

[edit | edit source]So far, everything we've written has been simple sentences — "My name is Santiago" (Me llamo Santiago); "The city is noisy" (La ciudad es ruidosa); "I play American football" (Juego al fútbol americano). Wouldn't it be fantastic if we could join them up? Below are some little words that will make our sentences longer, and more meaningful. You use them just like you do in English.

Also, everything we've written has been positive ("I do this, I do that"). To make it negative, we just add a word in front of the verb: no (meaning "not") or nunca (meaning "never"). For example, No juego al rugby (I don't play rugby"); Nunca como manzanas ("I never eat apples"). It's as simple as that.

|

Spanish Vocabulary • Print version

| |

|---|---|

| Inglés | Español |

| And | Y ; E (before i, hi, y) |

| Or | O |

| Because | Porque |

| But | Pero |

| Also | También |

| So | Así |

- Note

- Porque ("because") and Por qué ("why") are similar and easy to mix up; make sure you don't!

- Examples

- Me llamo Chris y mi cumpleaños es el veinte de agosto.

- My name is Chris and my birthday is on the 20th of August.

- Hay dos direcciones: derecha e izquierda.

- There are two directions: right and left one.

- Me llamo Raúl, pero él se llama Roberto.

- My name is Raúl, but his name is Robert.

- No practica judo.

- He doesn't do judo.

- Juego al fútbol americano y practico natación también.

- I play American football and I go swimming too.

- No vivo en una ciudad porque las ciudades son ruidosas.

- I don't live in the city because cities are noisy.

¿Qué opinas sobre los deportes?

[edit | edit source]To ask someone about their opinions in Spanish, use Qué opinas sobre ("What is your opinion about") then the thing you want their opinion on (¿Que opinas sobre los deportes? means "What do you think about sports?").

Gustar

[edit | edit source]There is no verb for "to like" in Spanish. Instead, you use gusta (meaning "it pleases") and a personal pronoun; you say that "it pleases me" or "I am pleased by it". The personal pronouns are shown below.

| Inglés | Español |

|---|---|

| Me | Me |

| You | Te |

| Him/Her/It | Le |

| Us | Nos |

| All of you | Os |

| Them | Les |

- Notes

- Like any other verb, you can put no in front of it, to say "I don't like" (No me gusta).

- If you like an activity rather than a thing, just use the infinitive afterwards: "I like swimming" (Me gusta nadar).

- Gusta means "it pleases", so only works for singular things. If the thing that you like is plural (the women for example), you add "n"; because, in Spanish, the thing that you like (women, in this case) is the subject of the sentence: me gustan las mujeres ("I like women").

Love and Hate

[edit | edit source]Just saying you like or dislike something is a bit dull. Saying you love something is really easy. Instead of gusta, use encanta (Me encanta leer means "I love reading"). To say you hate something, use the regular verb Odiar (odio, odias, odia, odiamos, odiáis, odian).

You can also use nada or mucho to add emphasis to gusta. For example, No me gusta nada ver la tele ("I don't like watching TV at all"); Me gusta mucho el ajedrez ("I like chess a lot").

- Examples

- ¿Qué opinas sobre el ajedrez?

- What do you think of chess?

- Me gusta el críquet.

- I like cricket.

- No le gustan los deportes.

- He doesn't like sports.

- Nos gusta jugar al rugby y fútbol.

- We like playing rugby and football.

- Les gusta mucho nadar, pero no pueden cantar.

- They like swimming a lot, but they can't sing.

- ¿Te gusta practicar la natación?

- Do you like going swimming?

- ¿Por qué os gusta el tenis?

- Why do (all of) you like tennis?

- Odian el ajedrez.

- They hate chess.

- Me encantan los deportes, así vivo en la ciudad.

- I love sports, so I live in the city.

Summary

[edit | edit source]In this lesson, you have learned:

- How to say some sports and activities (el rugby; la natación; cantar).

- How to say you play and do these things (juego al rugby; practicamos natación).

- About a few stem-changing verbs (encuentro, encuentras, encuentra, encontramos, encontráis, encuentran)

- How to make longer and negative sentences (no; nunca; así; pero).

- How to ask for opinions (¿Qué opinas sobre el fútbol?; ¿Te encanta leer?)

- How to express opinions (Me gusta; Le gustan; Me encanta; Odiamos)

You should now do the exercise related to each section (found here), and translate the dialogue at the top before moving on to lesson 6...

|

¡Aprovéchalo! |

|

Lesson six

[edit | edit source]

Dialogue

[edit | edit source]| Vocabulary | |

|---|---|

| Necesitar | To need |

| Zumo de | Juice [of] |

- Raúl: Hola. ¿Qué compras?

- Sofía: Hola, Raúl. Compro una barra de pan y una botella de leche.

- Raúl: Vale. Así, ¿tomas leche y pan tostado para tu desayuno?

- Sofía: Sí. Y tú, ¿qué desayunas?

- Raúl: Normalmente, tomo zumo de naranja y una manzana.

- Sofía: Y ¿tienes la comida que necesitas?

- Raúl: Sí. Adiós.

- Sofía: ¡Hasta luego!

Translation (wait until the end of the lesson).

Food and Drink

[edit | edit source] |

|

|

|

|

| Pan (m) | Queso (m) | Huevo (m) | Arroz (m) | Pasta (f) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Tomate (m) | Lechuga (f) | Pepino (m) | Zanahoria (f) | Patata (f) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Manzana (f) | Plátano (m) | Naranja (f) | Pera (f) | Uva (f) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Agua (m) | Leche (f) | Vino (m) | Café (m) | Té (m) |

- Notes

- (m) above indicates that the noun is masculine (el queso — "the cheese"; los plátanos — "the bananas"), whereas (f) above indicates that it is feminine (la lechuga — "the lettuce"; las uvas — "the grapes")

- In South America, papa is used instead of patata and Plátano refers to a plantain or cooking banana whereas a normal sweet banana is known as a banana or banano.

- While agua is feminine, it takes the masculine articles un and el. For example, el agua curiosa ("the strange water") and las aguas curiosas ("the strange waters"). This is because agua starts with an accented a.

- Con means "with", sin means without (café con leche means "coffee with milk", café sin leche means "coffee without milk").

- Wine comes in two varieties, "red" and "white". In Spanish, they are called vino tinto and vino blanco.

- Examples

- Me gustan los huevos.

- I like eggs.

- No me gusta nada la lechuga.

- I don't like lettuce at all.

- Me encanta el té con leche.

- I love tea with milk

- Me gustan mucho las zanahorias, pero los pepinos son aburridos.

- I like carrots a lot, but cucumbers are boring.

What do you eat?

[edit | edit source]To ask what someone else eats, use Qué followed by a form of one of the verbs below (¿Qué comes? means "What do you eat?"). To ask what someone likes to eat, use Qué te gusta then any of the verbs below (¿Qué te gusta comer? means "What do you like to eat?").

|

Spanish Verbs • Print version

| |

|---|---|

| Español | Inglés |

| Comer | To eat |

| Beber | To drink |

| Tomar | To have (food/drink) |

| Desayunar | To (eat) breakfast |

| Almorzar [in Spain, comer] | To (eat) lunch |

| Cenar | To dine (eat dinner) |

- Note

All of these verbs are regular except almorzar, which is one of the UE Verbs we learnt about in the last chapter; almuerzo, almuerzas, almuerza, almorzamos, almorzáis, almuerzan.

- Examples

- ¿Qué te gusta almorzar?

- What do you like to eat for lunch?

- Como naranjas y plátanos, pero no me gustan las peras.

- I eat oranges and bananas, but I don't like pears.

- Me gusta comer uvas.

- I like to eat grapes.

- ¿Bebes leche?

- Do you drink milk?

A bottle of wine

[edit | edit source]|

Spanish Verbs • Print version

| |

|---|---|

| Español | Inglés |

| Algo de | Some |

| Un vaso de | A glass of |

| Una copa de | |

| Una botella de | A bottle of |

| Una barra de | A loaf of |

| Un kilo de | A kilo of |

| Un kilo y mediο de | One and a half kilos of |

| Un kilo y cuarto de | One and a quarter kilos of |

| Μedio kilo de | Half a kilo of |

| Un cuarto de kilo de | A quarter of a kilo of |

- Notes

- We previously learnt "unos/unas" as the translation for "some", e.g. unas manzanas ("some apples"), but this only works for plural nouns. "Some bread" has to be translated as algo de pan or just pan.

- Also, there are two ways of saying "a glass of". Copa is for glasses with a stem (mostly wine: una copa de vino), and vaso is used for without a stem.

- Obviously, in all these phrases, the un can be replaced with any number (Dos vasos de leche means "two glasses of milk").

- Examples

- Tres botellas de vino tinto

- Three bottles of red wine

- Un medio kilo de arroz

- Half a kilo of rice

- Una barra de pan

- A loaf of bread

- Cinco kilos y medio de patatas

- Five and a half kilos of potatoes

In the Shop

[edit | edit source]In Spanish, as in English, there are many ways of expressing what you would like to buy, some of which are listed below. You will also see some other useful words and phrases to use when shopping for food.

|

Spanish Verbs • Print version

| |

|---|---|

| Español | Inglés |

| Quisiera | I would like |

| Querría | |

| Me gustaría | |

| Ahí está(n) | There you go; voila. |

| Comprar | To buy |

| La cuenta | The bill / account |

| Cobrar | To settle in cash |

| Costar | To cost |

| Una tienda | A shop |

- Notes

- Comprar is a regular verb (compro, compras, compra, compramos, compráis, compran).

- With ahí está(n), the n is added if the noun is plural.

- Costar is a O => UE verb (cuesto, cuestas, cuesta, costamos, costáis, cuestan), but obviously, you only use the third person.

- Also, if you want to say "How much does it cost?" you use ¿Cuánto cuesta(n)? (cuesta is for singular things, cuestan for plurals, as seen below).

- In a bar or café in Spain, one usually pays for everything on leaving ¿La cuenta, por favor? is to ask for the bill and it relates to the verb contar - to count or to tell. Alternatively cobrar (collect) relates to payment (or cash) ¿me cobra? = may I pay?

- Examples

- Quisiera una manzana, por favor.

- I would like an apple, please.

- Querría comprar una barra de pan.

- I'd like to buy a loaf of bread.

- Me gustaría comprar una botella de vino tinto, por favor.

- I'd like to buy a bottle of red wine, please.

- ¿Cuánto cuestan las uvas?

- How much do the grapes cost?

- ¿Cuánto cuesta un kilo de patatas?

- What does a kilo of potatoes cost?

Adjectives

[edit | edit source]"E" and Consonant Adjectives

[edit | edit source]In Spanish, clearly not all adjectives end in "o" or "a". The good thing about these is that they stay the same, irrespective of gender.

- Adjectives ending in "e" add an "s" when in the plural.

- Adjectives ending in a consonant add an "es" when in the plural.

- Notes

- When an adjective (or indeed a noun) ends in z, it changes to a c in plural, then adds the "es" (feliz/felices — "happy").

- Examples

|

|

Colours

[edit | edit source]Colours in Spanish are just adjectives, so they still have to agree and go after the noun. They are shown below.

| Inglés | Español | |

|---|---|---|

| Red | Rojo(a) | |

| Orange | Naranja / Anaranjado(a) | |

| Yellow | Amarillo(a) | |

| Green | Verde | |

| Blue | Azul | |

| Purple | Morado(a) / Violeta | |

| Brown | Marrón / Pardo(a) / Café | |

| Pink | Rosa / Rosado(a) | |

| White | Blanco(a) | |

| Grey | Gris | |

| Black | Negro(a) | |

- Notes

- Adjectives can function as nouns if you add an article in front of them. For example, el morado means "the purple one".

- Take care with Brown!

- The plural form of marrón is marrones (without the accent); las zanahorias marrones means "the brown carrots".

- Marrones glacés are (in Spanish as in Italian) candied chestnuts.

- Hair and eyes color brown is usually Castaño (chesnut). Brown skin color is Moreno (tanned).

- The adjective negrita (Literally:little black/bold face) is a term of familiarity or endearment is in Spanish and not to be confused with an offensive English expression.

- Naranja is only the noun form of the word; when used as an adjective, anaranjado is used.

- The color rosa ends in "a" even if applied to a masculine noun; el balón rosa, "the pink ball"

- Examples

- La manzana verde

- The green apple

- Los huevos blancos

- The white eggs

- El queso amarillo

- The yellow cheese

- Las naranjas anaranjadas

- The orange oranges

Summary

[edit | edit source]In this lesson, you have learnt

- How to say some foods and drinks (la lechuga; una manzana; la leche).

- How to say you eat and drink things (como, comes, come, comemos, coméis, comen).

- How to say some simple quantities (un kilo de patatas; una copa de vino tinto)

- What to say in a shop (quisiera; querría; la cuenta).

- How to form adjectives that don't end in "O" or "A" (la tienda verde; los quesos azules)

You should now do the exercise related to each section (found here), and translate the dialogue at the top before moving on.

You have now completed this chapter! Return to the Contents...

|

¡Aprovéchalo! |

|

Pronunciation

[edit | edit source]Pronouncing Spanish based on the written word is much simpler than pronouncing English based on written English. This is because, with few exceptions, each letter in the Spanish alphabet represents a single sound, and even when there are many possible sounds, simple rules tell us which is the correct one. In contrast, many letters and letter combinations in English represent multiple sounds (such as the ou and gh in words like cough, rough, through, though, plough, etc.).

Letter-sound correspondences in Spanish

[edit | edit source]The table below presents letter-sound correspondences in the order of the traditional Spanish alphabet. (Refer to the article Spanish orthography in Wikipedia for details on the Spanish alphabet and alphabetization.)

| Letter | Name of the letter |

IPA | Pronunciation of the letter (English approximation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A a | a | a | Like a in father |

| B b | be, be larga, be alta | b | Like b in bad. |

| β | Between vowels, the lips should not be fully closed when pronouncing the sound (somewhat similar to the v in value, but much softer). | ||

| C c | ce | θ/s | Before the vowels e and i, like th in thin (most of Spain) or like c in center (Parts of Andalucía, Canary Islands and Americas). |

| k | Everywhere else; like c in coffee | ||

| Ch ch | che | tʃ | Like ch in church. |

| D d | de | d | Does not have an exact English equivalent. Sounds similar to the d in day, but instead of the tongue touching the roof of the mouth behind the teeth, it should touch the teeth themselves. |

| ð | Between vowels, the tongue should be lowered so as to not touch the teeth (somewhat similar to the th in the). | ||

| E e | e | e | Like e in ten, and the ay in say. |

| F f | efe | f | Like f in four. |

| G g | ge | g | Like g in get. |

| ɰ | Between vowels (where the second vowel is a, o or u), the tongue should not touch the soft palate (no similar sound in English, but it's somewhat like Arabic ghain). | ||

| x | Before the vowels e and i, like a Spanish j (see below). | ||

| H h | hache | Silent, unless combined with c (see above). Hu- or hi- followed by another vowel at the start of the word stand for /w/ (English w) and /j/ (English y). Also used in foreign words like hámster, where it is pronounced like a Spanish j (see below). | |

| I i | i | i | Like e in he. Before other vowels, it approaches y in you. |

| J j | jota | x | Like the ch in loch, although in the majority of the dialects, it is pronounced like an English h. |

| K k | ka | k | Like the k in ask. This letter is limited in Spanish since it is mostly only used in words of foreign origin - Spanish prefers using c and qu (see above and below, respectively) as replacements for the letter k. |

| L l | ele | l | Does not have an exact English equivalent. It is similar to the English "l" in line, but shorter, or "clipped." Instead of the tongue touching the roof of the mouth behind the teeth, it should touch the tip of the teeth themselves. |

| Ll ll | doble ele, elle | ʎ/ʝ | Pronounced, mostly in Northern Spain, like gl in the Italian word gli. Does not have an English equivalent, but it's somewhat similar to li in million. In other parts of Spain and in Latin America, ll is commonly pronounced as /ʝ/ (somewhat similar to English y, but more vibrating). In Argentina and Uruguay it can be like sh in "flash" or like the s in the English "vision". |

| M m | eme | m | Like m in more. |

| N n | ene | n | Like n in no. Before p, b, f and v (and in some regions m) sounds as m in important. For example un paso sounds umpaso. Before g, j, k sound (c, k , q), w and hu sounds like n in anchor: un gato, un juego, un cubo, un kilo, un queso, un whisky, un hueso. Before y sound (y or ll), it sounds like ñ, see below. |

| Ñ ñ | eñe | ɲ | Like gn in the Italian word lasagna. As it's always followed by a vowel, the most similar sound in English is /nj/ (ny) + vowel, as in canyon, where the y is very short. For example, when pronouncing "años", think of it as "anyos", or an-yos. To practice, repeat the onomatopoeia of chewing: "ñam, ñam, ñam". |

| O o | o | o | Like o in more, without the following r sound. |

| P p | pe | p | Like p in port. |

| Q q | cu | k | Like q in quit. As in English, it is always followed by a u, but unlike in English since letter q only occurs before e or i, the u is silent in Spanish (líquido is pronounced /'li.ki.ðo/). The English /kw/ sound is normally written cu in Spanish (cuanto), although qu can be used for this sound in front of a or o (quásar, quórum). |

| R r | ere, erre | ɾ | This has two pronunciations, neither of which exist in English. The 'soft' pronunciation [ɾ] sounds like American relaxed pronunciation of tt in "butter", and is written r (always written r). |

| r | The 'hard' pronunciation [r] is a multiply vibrating sound, similar to Scottish rolled r (generally written rr). 'Hard' r is also the sound of [r] at the start of a word or after l, n or s. | ||

| S s | ese | s | Like s in six. In many places it's aspirated in final position, although in Andalusia it is not itself pronounced, but changes the sound of the preceding vowel. (See regional variations). In most parts of Spain, it's pronounced as a sound between [s] and [ʃ]. |

| T t | te | t | Does not have an exact English equivalent. Like to the t in ten, but instead of the tongue touching the roof of the mouth behind the teeth, it should touch the teeth themselves. |

| U u | u | w | before another vowel (especially after c), like w in twig. |

| In the combinations gue,gui and qu, it is silent unless it has a diaresis (güe, güi), in which case it is as above: w (only in the combinations güe and güi and not in the combination qü). | |||

| u | Everywhere else, like oo in pool, but shorter. | ||

| V v | uve, ve, ve corta, ve baja | b, β | Identical to Spanish b (see above). |

| W w | uve doble, doble ve, doble u | b, β, w | This letter is hardly almost ever used in Spanish since it is only used in words of foreign origin (Spanish prefers using u or v). Pronunciation varies from word to word: watt is pronounced like bat or huat, but kiwi is always pronounced like quihui. |

| X x | equis | ks | Like ks (English x) in extra. In some cases it may be pronounced like gs or s. |

| ʃ | In words of Amerindian origin, like sh in she. | ||

| x | Note that x used to represent the sound of sh, which then evolved into the sound now written with j. A few words have retained the old spelling, but have modern pronunciation /x/. Most notably, México and its derivatives are pronounced like Méjico. | ||

| Y y | i griega, ye | i | It sounds as a vowel [i]: a. when it is a word itself (y /i/, meaning "and" in English), b. at the end of a word like in rey /rei/ ("king"), c. in the middle of a compound word like in Solymar (sol y mar /so.li'mar/, meaning "sun and sea"), d. at the beginning of a word followed by a consonant in words or names that have retained an old spelling (Yfrán /i'fɾan/). |

| ʝ | It sounds as a consonant [ʝ] in any other position: reyes /'re.ʝes/, yeso /'ʝe.so/. This standard pronunciation for y as a consonant does not have a perfect English equivalent, but it is somewhat similar to English y (just more vibrating). In Argentina and Uruguay y is pronounced similar to the English sh (/ʃ/) in she, or /ʒ/ (like English s in vision). | ||

| Z z | zeta, ceda | θ, s | Always the same sound as a soft c i.e. either /θ/ (most of Spain) or /s/ (elsewhere). See c for details. |

One letter, one sound

[edit | edit source]Pronouncing Spanish based on the written word is much simpler than pronouncing English based on written English. Each vowel represents only one sound. With some exceptions (such as w and x), each consonant also represents one sound. Many consonants sound very similar to their English counterparts.

As the table indicates, the pronunciation of some consonants (such as b) does vary with the position of the consonant in the word, whether it is between vowels or not, etc. This is entirely predictable, so it doesn't really represent a breaking of the "one letter, one sound" rule.

The University of Iowa has a very visual and detailed explanation of the Spanish pronunciation.

Here is another page with links to the audio files of the letters.

Only five letters may be doubled, and they are the ones in CLEAR.

Examples: Accento, amarillo, leer, Isaac, and arriba.

Local pronunciation differences

[edit | edit source]Word stress

[edit | edit source]In Spanish there are two levels of stress when pronouncing a syllable: stressed and unstressed. To illustrate: in the English word "thinking", "think" is pronounced with stronger stress than "ing". If both syllables are pronounced with the same stress, it sounds like "thin king".

With one category of exceptions (-mente adverbs), all Spanish words have one stressed syllable. If a word has an accent mark (´; explicit accent), the syllable with the accent mark is stressed and the other syllables are unstressed. If a word has no accent mark (implicit accent), the stressed syllable is predictable by rule (see below). If you don't put the stress on the correct syllable, the other person may have trouble understanding you. For example: esta, which has an implicit accent in the letter e, means "this (feminine)"; and está, which has an explicit accent in the letter a, means "is." Inglés means "English," but ingles means "groins."

Adverbs ending in -mente are stressed in two places: on the syllable where the accent falls in the adjectival root and on the men of -mente. For example: estúpido → estúpidamente.

The vowel of an unstressed syllable should be pronounced with its true value, as shown in the table above. Don't reduce unstressed vowels to neutral schwa sounds, as occurs in English.

Rules for pronouncing the implicit accent

[edit | edit source]There are only the following rules for pronouncing the implicit accent. The stressed syllable is in bold letters:

- If a word ends with a vowel or with n or s , the next-to-last syllable is stressed.

Examples:- cara (ca-ra) (face)

- mano (ma-no) (hand)

- amarillo (a-ma-ri-llo) (yellow)

- hablan (ha-blan) (they speak)

- martes (mar-tes) (Tuesday)

- If a word ends with a consonant other than n or s, the last syllable is stressed.

Examples:- farol (fa-rol) (street lamp)

- azul (a-zul) (blue)

- español (es-pa-ñol) (Spanish)

- salvador (sal-va-dor) (savior).

- A syllable usually contains exactly one vowel. If there are two adjacent vowels, they count as two distinct syllables if both are one of a,e and o. If, however, at least one of them is i or u, they count as only one syllable. If, according to the two rules above, that syllable is stressed, the first of the two vowels is stressed if it is one of a, e and o, while the second vowel is stressed if the first one is one of i and u.

Examples:- correo (co-rre-o) (mail)

- hacia (ha-cia) (in the direction of)

- fui (fu-i) (I was) (Note that this word has only one syllable.)

Any exception to these rules is marked by writing an acute accent (máximo, paréntesis, útil, acción). In those exceptions, the stressed syllable is the one where the acute accent (called tilde in Spanish) appears.

The diéresis ( ¨ )

[edit | edit source]In the clusters gue and gui, the u is not pronounced; it serves simply to give the g a hard-g sound, like in the English word gut (gue → [ge]; gui → [gi]).

However, if the u has a the diaeresis mark (¨), it is pronounced like an English w (güe → [gwe]; güi → [gwi]). This mark is rather rare.

Examples:

- pedigüeño = beggar

- agüéis (2nd person plural, present subjunctive of the verb aguar). Here, the diaeresis preserves the u (or [w]) sound in all the verb tenses of aguar.

- argüir (to deduce)

- pingüino = penguin

|

¡Aprovéchalo! |

|

Contributors

[edit | edit source]The Spanish Wikibook was created on August 2, 2003 by ThomasStrohmann; it was the first language book on Wikibooks. During December 2006, it underwent a complete archive and rewrite, by Celestianpower. A list of major contributors — past and present — can be found below.

- ThomasStrohmann

- Karl Wick

- Wintermute

- Mariela Riva

- Mxn

- Sabbut

- Javier Carro

- Fenoxielo

- Think Fast

- Celestianpower

- John D'Adamo

- AnthonyBaldwin

- Flickts

- Neoptolemus

- Akhram

|

¡Aprovéchalo! |

|