Cookbook:Beef

| Beef | |

|---|---|

| |

| Category | Meat and poultry |

Cookbook | Recipes | Ingredients | Equipment | Techniques | Cookbook Disambiguation Pages | Ingredients | Basic foodstuffs | Meat and poultry

Beef is meat obtained from a bull, steer (castrated bull), or cow.

Production

[edit | edit source]There are two primary beef rearing methods. In some parts of the world (e.g. Australia and South America), beef cattle self-feed on grass and weeds while roaming around. This produces beef with fat deposits on the outsides of the beef cuts, where they can be removed before cooking. In the USA and some other countries, feedlot beef is much more common. These animals are confined to a small stockyard and fed primarily on grain. Feedlot animals produce beef which is tender, mild flavored, and marbled with large amounts of fat.

There is a special kind of beef produced in Japan called Kobe beef, which goes a step beyond feedlot production. Beef cattle of the Wagyu breed are hand-raised, fed on a diet of beer and quality grain, and given regular massages. This produces super-tender beef with lots of marbled fat. Kobe beef sells at a premium price because of the higher costs of feed and production.

After slaughter, beef must be allowed to rest and naturally tenderize before cooking. The tenderizing process may go a step further with dry aging, where beef is allowed to carefully putrefy under controlled cold and dry conditions. This concentrates its flavor and creates a more tender texture.[1]

Characteristics

[edit | edit source]

Beef is considered a red meat due to its higher levels of myoglobin. Very fresh meat that has not been exposed to oxygen will have a purpleish color. Once exposed to oxygen, the meat will turn bright red and eventually oxidize to brown after over a week. Beef fat is distributed both around individual cuts and within the muscle, the latter of which is called marbling. The more marbling, the more flavorful and tender the beef after cooking.[2]

Beef is high in flavor compared to lighter meats, and it works well in many applications. It takes well to strong flavors. Beef from different parts of the animal will differ in flavor and texture. Generally, the more flavorful the meat, the less tender, and vice versa. Beef increases in tenderness the higher up it is on the animal, as the less-used muscles are the tenderest. Animal age also impacts the beef's tenderness, with younger animals producing more tender meat.

Grading

[edit | edit source]The USDA beef rating system encourages beef with high amounts of intramuscular fat by giving high scores to highly-marbled beef. From least marbled to most marbled, the grades are standard, select, choice, and prime. Subdivisions have recently been added; a "-" indicates a cut with less marbling while a "+" indicates more marbling. The letter grades refer to age of the animal, with "A" being for the youngest animals.

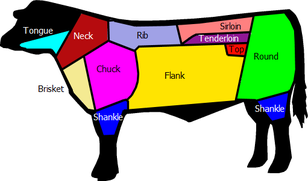

Cuts

[edit | edit source]After slaughter, beef is divided into several sections called cuts, which are then further subdivided into smaller sections for serving. Different regions have different standards for cuts, depending on local cuisines and regulatory bodies.[2] In continental Europe, cuts tend to derive from individual muscles,[1] and each cut will primarily consist of one muscle group—this results in consistency of flavor and texture across the cut. In the UK and North America, some cuts may consist of multiple muscle groups.[1]

American Cuts

[edit | edit source]

In the United States, beef is first divided into the following large "primal" cuts:[3][4]

Brisket is a dense, tough cut from the chest of the animal. It is fatty and flavorful, and it is best suited for long slow cooking, such as slow roasting and braising.

Chuck is derived from the shoulder. It is somewhat fatty and tough but has good flavor.[5] Some smaller cuts from the chuck are flat-iron steak, stew meat, chuck roast, chuck short ribs, and top blade steaks. It is also often used for ground beef.

Flank cuts are tough with a low fat content. It is suitable for braising. Cuts from the flank include flank steak and london broil. It is often recommended to cut flank across the grain to avoid excess chewiness.

The loin is a very tender cut of beef near the rear of the animal.[1] The short loin is the most tender, and yields smaller cuts including tenderloin, filet mignon, strip steak and roast, T-bone steak, and porterhouse steak. The sirloin is slightly less tender than the loin and yields sirloin steak, tri-tip, ball tip, and sirloin flap, among others. If too lean, loin cuts can end up bland and lacking in flavor.[1]

The plate comes from the abdomen. Its smaller cuts include skirt steak and short ribs.

Rib cuts are generally tender cuts from the middle of the animal, which often feature marbling.[1] They include short ribs, rib-eye steak, rib-eye roast, cowboy steak, and back ribs.

The round is generally lean, tough, and inexpensive. It yields various roasts and some round steaks.

The shank comes from the leg of the animal. It is very tough and requires slow cooking, but it has excellent flavor.[2]

Bones

[edit | edit source]Beef bones contribute a good deal of flavor,[2] which is usually extracted in stocks and broths. Marrow bones are thick bones from the shank, and the soft fatty marrow in the center is nutrient dense and rich—it can be spread on foods.[5]

Offal

[edit | edit source]Beef heart is somewhat springy. Other beef variety meats include the tongue, tripe from the stomach, various glands—particularly the pancreas and thyroid—referred to as sweetbreads, the brain, the liver, the kidneys, and the tender testicles of the bull commonly known as "calf fries", "prairie oysters", or "Rocky Mountain oysters."

Selection and storage

[edit | edit source]When choosing beef, look for bright red meat. It should smell fresh and have no off colors.

Use

[edit | edit source]The method used to cook beef often depends on the cut. Tougher pieces of beef with more connective tissue benefit from long, slow, moist cooking—this breaks down the collagen and produces a tender and melting final product.[1] Tender cuts can be quickly cooked using dry heat, but they can easily become overcooked and will then suffer in texture.[1]

Several Asian and European nationalities include beef blood in their cuisine—the British use it to make black pudding, and Filipinos use it to make a stew called dinuguan. Tongue is usually sliced for sandwiches.

Recipes

[edit | edit source]References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ a b c d e f g h Green, Aliza (2012-06-01). The Butcher's Apprentice: The Expert's Guide to Selecting, Preparing, and Cooking a World of Meat. Quarry Books. ISBN 978-1-61058-393-0.

- ↑ a b c d America, Culinary Institute of; Schneller, Thomas (2009-02-03). Kitchen Pro Series: Guide to Meat Identification, Fabrication and Utilization. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-111-78059-3.

- ↑ https://www.thespruceeats.com/cuts-of-beef-chuck-loin-rib-brisket-and-more-995304

- ↑ https://www.clovermeadowsbeef.com/beef-cuts/

- ↑ a b Labensky, Sarah R.; Hause, Alan M.; Martel, Priscilla (2018-01-18). On Cooking: A Textbook of Culinary Fundamentals. Pearson. ISBN 978-0-13-444190-0.